HABITATS AND VEGETATION IN JAPAN

Japan is one of the most densely forested countries on Earth. Forests and woodland cover around 66 percent of the land. The northern forests include fir and spruce. Central Japan has mixed forests of beech, maple, and oak. Deciduous trees dominate in the south. Cherry trees and bamboo are found throughout Japan. [Source: World Encyclopedia, Oxford University Press 2005]

Hokkaidō flora is characterized by montane conifers, or cone-bearing trees (fir, spruce, and larch), at high altitudes, and mixed northern hardwoods (oak, maple, linden, birch, ash, elm, and walnut) at lower altitudes. Ground flora includes plants common to Eurasia and North America. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

On Honshu, common conifers are cypress, umbrella pine, hemlock, yew, and white pine. On the lowlands, there are live oak and camphor trees and a great mixture of bamboo with the hardwoods. Black pine and red pine make up most of the plants on the sandy lowlands and coastal areas.Shikoku and Kyushu are noted for their evergreen plants. Sugarcane and citrus fruits are found throughout the lowland areas, with broadleaf trees in the lower elevations and a mixture of evergreen and deciduous trees higher up. Throughout these islands are rich growths of bamboo.

Climate change could squeeze out plants and animals that live in delicate alpine and northern regions. Already tropical plants are growing in subtropical areas and subtropical plants are growing temperate areas and crabs and fish normally found in tropical waters have been found in normally temperate waters off Japan. The beech forests in northern Japan are expected to disappear while the number of allergy-causing Japanese cedars is expect to increase. Beeches thrive in regions with cool summers and lots of snow in the winter. They are threatened and already being pushed northward by global warming. Other changes that have already occurred include changes in the flowering of cherry trees, a decease in alpine flora in Hokkaido and high mountain areas and an expansion of the distribution of broadleaf evergreen trees,

RELATED ARTICLES:

PLANTS IN JAPAN: FLOWERS, ORCHIDS, MARIMO BALLS, KUDZU, BAMBOO factsanddetails.com

TREES IN JAPAN: SUGI (CEDARS), ALLERGIES, HINOKI factsanddetails.com

TIMBER, LUMBER AND FORESTRY JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Forests in Japan

Japan is one of the world's most heavily forested countries. Before humans began altering the landscape, almost all the Japanese islands were covered by forest. Today there are 252,120 square kilometers (62.3 million acres) of forest in Japan, covering more than two-thirds of the country's mountainous land area. This is remarkable considering that Japan is also one of the world's most densely populated countries. About 68.5 percent of Japan’s land is covered with forest. This figure is third behind Finland (72.9 percent) and Sweden (68.7 percent), and over twice the world average of 31 percent. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, February 28, 2013]

Japan has a mild climate and plentiful rain which are ideal for forest growth. With the exception of some extreme habitats such as alpine meadows and areas of river gravel Japan's natural cover is almost always forest. Many of the last virgin forests are protected as "Wilderness Areas." Some of the nicest forests are found around Shinto shrines, where forests have been preserved. In urban areas often the only place you can find large numbers of trees is in sacred graves found around Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines.

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Major Japanese timber trees include sugi cryptomeria (Cryptomeria japonica), hinoki cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa), sawara cypress (C. pisifera) and karamatsu larch (Laris leptolepis). Of these, the cryptomeria is by far and away the most commonly planted. This is an endemic Japanese species, distributed from northern Honshu south to Yakushima Island in Kagoshima Prefecture. Typical natural habitat is in deep muddy soils near the bottom of steep ravines, especially on shaded north-facing slopes. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, February 28, 2013] Japan’s forest resources, although abundant, have not been well developed to sustain a large lumber industry. Of the 24.5 million hectares of forests, 19.8 million are classified as active forests. Most often forestry is a part-time activity for farmers or small companies. About a third of all forests are owned by the government. Production is highest in Hokkaido and in Aomori, Iwate, Akita, Fukushima, Gifu, Miyazaki, and Kagoshima prefectures. Nearly 33.5 million cubic meters of roundwood were produced in 1986, of which 98 percent was destined for industrial uses. [Source: Library of Congress, 1994 *]

See Separate Article: TIMBER, LUMBER AND FORESTRY JAPAN factsanddetails.com

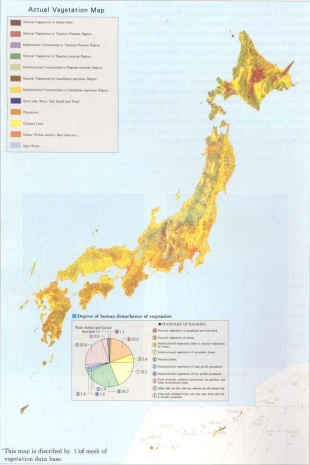

Forests in Different Parts of Japan

There are three main kinds of natural forests in Japan: 1) coniferous forest of spruce and fir in alpine zones and eastern and northern Hokkaido: 2) cool-temperature deciduous forests with oaks and beeches, in central Honshu and southern Hokkaido; and 3) broadleaf evergreen forests with laurel and chiquapin in western Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu. Unlike, tropical rain forests, Japanese forests grow back quickly after they are cut down.

More localized and less widespread forests include: 1) subtropical rain forests with large trees, large ferns and strangler vines in the Amami-Oshima Islands and Okinawa Prefecture; 2) coastal forests, with trees that thrive under windy conditions; 3) mangrove forests found in some places in the islands south of Kyushu in Okinawa Prefecture; 4) Riparian forests, found along mountains streams; 5) sub-alpine forests with ground hugging trees like dwarf pines and stunted birch that do well in cold, windswept places.

There are large beech forest in northern Japan. Beeches thrive in regions with cool summers and lots of snow in the winter. They are threatened and already being pushed northward by global warming.

Some of the healthiest and most beautiful forests in Japan are in the Tohuku region, where rich forests with a wide variety of different tree species cover entire mountainsides and watersheds. In Towada-Hachimantai National Park in Aomori Prefecture, for instance, one can find trees common in North America, Siberia and Europe such as oak, willow, cherry, dogwood, ash, alder, sumac, horse chestnut, fir, pine and birch.

Diversity of Japan’s Forests

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: An estimated 1,000 species of woody plants live in Japanese forests, which is about the same as the figure for all of North America. One reason for the amazing diversity of Japanese trees can be found in geologic history. The Japanese islands were almost completely free of ice during the last glacial period. In contrast, until 10,000 years ago much of northern and western Europe was covered by glaciers up to a kilometer thick. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, February 28, 2013]

“Geographical conditions also help support sylvan biodiversity. With warm oceans currents flowing on both sides, the Japanese archipelago is blessed with a mild, wet climate that is ideal for tree growth and forest development. In addition, the islands stretch a long way in the north-south direction, and climatic zones range from subtropical in the Ryukyu Islands to subarctic in parts of Hokkaido.

In Japan “warm currents flowing along the coasts on both sides of the islands ameliorate the climate, making it possible for various species of evergreen broad-leaved trees, called joryoku-koyo-ju in Japanese, to thrive. Typical Japanese species include live oaks, camellias, chinquapins and laurels. Forests composed of these trees are native to the warm temperate regions of south and western Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu and the subtropical Ryukyu Islands. Along the Sea of Japan, thanks to the warming influence of the Tsushima Current, these forests extend northward in a narrow coastal band as far as Akita Prefecture. Along the Pacific Ocean side, the Kuroshio or Japan Current allows them to creep up all the way to Miyagi Prefecture.” [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, January 20, 2011]

“Japan's subtropical and warm-temperate forests represent the northern and eastern fringe of one of the world's great forest traditions. Starting on the southeastern slopes of the Himalayas, Asia's evergreen broad-leaves stretch in a wide belt clear across southern China to the Pacific seaboard. Along their southern edge they include stretches in northern Myanmar and Vietnam. On reaching the coast, the warm currents permit them to sweep northward to Japan and the very tip of the Korean Peninsula.”

“These forests should not be confused with true tropical rainforests, which throughout the region border them on the south. The component species and overall ecosystem of these forest types are substantially different. To the north, the evergreen broad-leaved forests give way to cool temperate deciduous broad-leaved woods, which in Japan are dominated by beech and deciduous oak and are commonly called buna-rin, or "beech woods."

Evergreen broad-leaved trees have thick leaves that are often covered on the upper surface with a thick coat of waxy substance that affords some protection from the cold. This coating gives the leaves a bright shiny aspect, and in Japanese they are also called shoyo-ju, which means "shiny-leaf tree."

Artificial Forests in Japan

About 41 percent of the forests in Japan have been artificially planted, and 44 percent of the reforested areas have been planted with cedar. The cedars now make ups nearly 20 percent of Japan's forests. The remainder are made up mostly of valuable lumber trees such as Cryptomeria, hinoki, larch and cypress. Most forests are sterile conifer plantations made up of trees grouped by species and planted in neat, well-organized rows that cover entire mountainsides. Mountainsides are mosaics of single-species patches of trees that are easy for timber companies to work.

The majority of the conifer plantations were created in the years following World War II to cover areas that had been clear cut to provide fuel and lumber for Japan’s war-era military government. Forests with a single species packed so closely together that there is no undergrowth mean there is no food for animals. As a result there are very few mammals, birds and even insects in Japanese forests. Decades ago Japan supplied 80 percent of its timber needs from domestically grown trees. Today it supplies only 26 percent. In the 1980s the remainder came primarily from the dwindling tropical rain forests in Southeast Asia.

Forests are often owned and managed by paper companies and construction material companies that often do a pretty good job managing the forests for commercial needs. There are large number of larch trees in Hokkaido. Larch trees are not native to the region. In the 19th century large swath of virgin forest was cleared so that larch trees could be planted to supply wood for coal mines.

Deforestation in Japan

tree with Shinto ropes Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Unfortunately, Japan's evergreen broad-leaved forests have not fared very well. While large tracts of primary beech forests remain in the Tohoku and Shinshu regions, substantial old-growth evergreen forests have practically disappeared, especially on the main islands.” [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, January 20, 2011]

“The demise of these forests started about 3,000 years ago, when the technology for irrigated rice cultivation was transmitted to Japan from the Korean Peninsula. This new, highly productive wet rice lifestyle spread through the warm temperate areas, fueling population growth which in turn required more and more trees for fuel and lumber. This decline was accelerated when the Japanese began smelting iron, a process which requires huge amounts of firewood to keep the kilns (tatara) stoked.”

“This ecological relationship is admirably depicted in Studio Ghibli's excellent anime "Princess Mononoke" (Mononoke-hime). The plot involves an iron-smelting town in the Chugoku Mountains of western Honshu. The people there want to cut down the trees in the last remaining evergreen broad-leaved forest, but can't do so until the spirit guardians of the forest have been vanquished.”

“Wet rice cultivation eventually spread to the cool temperate zone as well, but never resulted in the huge population explosions that occurred further south. As a result, the native beech forests have historically fared much better. Extensive beech forests are still found throughout the Shirakami and Waga Mountains and other areas of the Tohoku region, but the only really significant old-growth shoyoju-rin is in Ayacho in central Miyazaki Prefecture. Otherwise, these forests can be found mostly in the sacred groves surrounding shrines and temples. The Grand Ise Shrines in Mie Prefecture and the Kasuga Taisha shrine in Nara are especially renowned for their magnificent evergreen broad-leaved groves.”

“In the Kanto area, much small remnants of the warm temperate forest can be found in the sacred groves surrounding local shrines and temples. Here the chief components of a natural grove are huge sudajii chinquapins and aka-gashi and shira-kashi live oaks. Beneath these grow Japanese camellias and other shrubs and smaller trees that are shade-tolerant.

“Some Japanese anthropologists have pointed out that Japan shares many cultural elements, such as tattooing, teeth-blackening, silk production, anko bean paste, sumac lacquerware and glutinous rice dishes, with continental peoples living in the evergreen broad-leaved zones. From this has arisen the concept of an "evergreen broad-leaved cultural tradition" (shoyojurin-bunkaron), stretching clear across the Asian continent.”

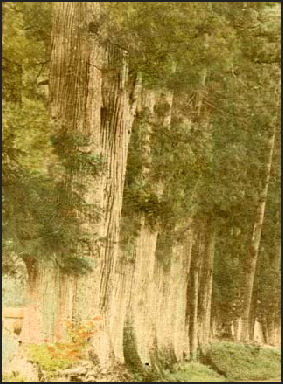

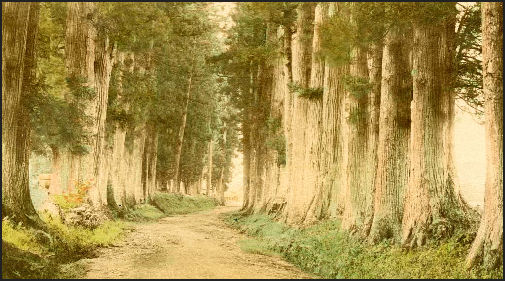

Sacred Groves in Japan

Sacred groves are protected trees surrounding Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. They range in size from a single trees planted alongside stone statues to large forests preserved behind major shrines and temples. It is thought that original Japanese shrines were simple groves of trees, with kami dwelling in the grove itself. There are also hundreds of sacred mountains and sacred water sites— ponds associated with water deities, wells linked to the Buddhist monk Kukai and waterfalls thought to be inhabited by dragons and deities such as Fudi Moo.

Sacred groves usually have very tall, old trees—often cedar trees. If you see a stand of tall trees there is a good chance that it is a sacred spot. Sacred groves are often situated near crossroads or village entrances for local guardian spirits. Some also regard them as portals to Yomi, the land of the dead, which is connected with the myth of creator god Izanagi seeking his wife Izanami in Yomi, after she scorched her genitals and perished after creating the fire kami. In some sacred groves phallic symbols made of stone or wood were raised to honor the union of guardian spirits and fertility gods.

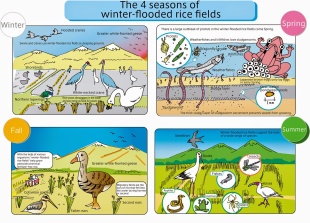

Rice Paddy Ecosystem

Rice paddies create a lovely landscape and have their own rich ecosystem. Fish such as minnows, loaches and bitterling can survive in the paddies and the canals as can aquatic snails, worms, frogs, crawfish beetles, fireflies and other insects and even some crabs. Egrets, kingfishers, snakes and other birds and predators feed on feed on these creatures. Ducks have been brought into rice paddies to eat weeds and insects and eliminate the need for herbicides and pesticides. Innovations such as concrete-sided canals have damaged the rice paddy ecosystem by depriving plants and animals of places they can live.

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, Paddies are entirely man-made habitats, built for the single purpose of growing rice. Ecologically, however, they function much like shallow wetlands. Many species of dragonfly and damselfly lay their eggs in the paddies, as do several types of frogs. Some farmers I know still carry a big glass jar with them when they set out to work in the paddies. Soon the jar is filled with wriggling loaches (dojo), which will provide their o-kazu side dish for the evening meal. As might be expected, this wealth of small animal prey attracts various birds to the rice paddies. Egrets and herons feed steadily all day long, and are usually considered to be the typical "paddy birds." At this time of year, however, they are joined for a short period by another group of very different birds, migratory sandpipers and plovers. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, May 19, 2011]

Kevin Short wrote in the Yomiuri, “Irrigated rice culture has been practiced in Japan for nearly 3000 years. Over these long centuries, some species of wild plants and animals have been driven high into the mountains by changes in the environment brought about by farming. Many others, however, have cleverly adapted their life cycles and behavior to take maximum advantage of habitats and feeding opportunities presented by the countryside landscape. The shrikes' seasonal movements may be one example of the latter.”

“A tractor harvesting rice usually attracts a bevy of opportunistic birds. As the rice is cut, frogs, snakes, lizards and insects that were hiding among the stalks are suddenly exposed and forced to run for their lives. The birds simply follow after the tractor, enjoying a welcome windfall feast. Typical tractor-groupies include egrets and herons, as well as starlings and crows, and occasionally shrikes.”

Rice Paddy Animals Match Their Time Cycle to Agricultural Rhythms

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Amazingly, many aquatic animals time their life cycles to precisely match the seasonal rhythms of rice farming. Japanese tree frogs (Hyla japonica or nihon amagaeru), for example, begin laying their eggs as soon as the paddies are filled with water in late April and early May. The eggs quickly hatch into tadpoles, which feed and grow steadily for a month or two. Now, just as the water is about to be drained from the paddies, the tadpoles are ready to metamorphose into tiny frogs. The new frogs are less than one centimeter long, and come crawling out of the paddies by the thousands. The aze dikes that separate the paddies are totally awash in invasion waves of baby frogs. [Source: Kevin Short, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 30, 2011]

The tree frogs' strategy for survival of the species is to come charging out of the paddies in overwhelming numbers. Baby frogs are the favorite prey of snakes and weasels, and just about any passing bird is happy to gobble up a few dozen. Only a miniscule percentage of the new frogs will survive the onslaught of predators, but this will be enough to ensure the next generation.

Also emerging from the paddies in large numbers are meadowhawk dragonflies. The tree frog eggs had been deposited this spring, but the dragonfly eggs had been laid last autumn. The eggs spend the winter in the soft paddy mud, then hatch out into aquatic larva, called naiads (yago in Japanese), as soon as the paddies are filled with water. The naiads grow and molt several times, and are ready to metamorphose into dragonflies just before the paddies are drained. The final stage naiads crawl up a rice stalk, then split open to reveal the beautiful adult dragonfly inside. The newly emerged adults are soft and vulnerable at first, and some time is needed for their wings to dry and harden before they can fly away. For this reason, the metamorphosis usually takes place at night, when fewer potential predators, especially sharp-eyed birds, are about.

The little egret, or ko-sagi, are aficionados of both dragonflies and new tree frogs. At this time of year they frequent the paddies and aze dikes, busily snapping up baby frogs by the hundreds. Egrets, herons and other long-legged wading birds depend heavily on the rice paddies for their food. They especially appreciate the sudden boost in easily caught new tree frogs, which comes just when they are raising their chicks in large communal nesting colonies known as sagi-yama (sagi is a generic term for a heron or egret).

The baby frogs are also an ideal size for newly hatched snakes. Snakes can only take prey that is small enough to swallow whole. A newly hatched snake could not swallow an adult frog, but a baby tree frog would be just right. These small snakes in turn are a favorite target for larger herons and also birds of prey such as the sashiba, or grey-faced buzzard eagle.

Satoyama

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: The Japanese countryside landscape, sometimes called the satoyama, is structured like a fine patchwork quilt or tile mosaic. An amazing variety of land-use patterns are jumbled together in a complicated manner. The individual patches are all small in area, and often isolated from others of their kind. Each type of land-use pattern contains its own distinctive set of tree species. The result is that a wide diversity of trees, shrubs and woody vines can be found within a very limited area. However, alien plant species have driven out native species in Japan. By one count there are 1,553 foreign plants, including dandelions, in Japan.[Source:Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, October 5, 2011]

Satoyama is often seen as a border zone or area between mountain foothills and arable flat land. “Sato” means village, and “yama” means hill or mountain. Satoyama have been developed through centuries of small-scale agricultural and forestry use and can mean: 1) the management of forests through local agricultural communities, using coppicing; or 2) the entire landscape including forests and land used for agriculture. Management of system dates back to the Edo era or later when young and fallen leaves were gathered from community forests to use as fertilizer in wet rice paddy fields. Villagers also used wood for construction, cooking and heating. The satoyama landscape contains mixed forests, rice paddy fields, dry rice fields, grasslands, streams, ponds, and reservoirs for irrigation. Farmers use the grasslands to feed horses and cattle. Streams, ponds, and reservoirs play an important role in adjusting water levels of paddy fields and farming fish as a food source. [Source: Wikipedia]

The mixed satoyama landscape facilitates the movement of wildlife between a variety of habitats. The migration of wild animals can occur between ponds, rice paddies, grasslands, forests, and also from one village to another. Ponds, reservoirs, and streams in particular play a significant role in the survival of water dependent species such as dragonflies, and fireflies. In the early stages of their life cycle, they spend most of their time in water. Deciduous oaks were planted by farmers in forest patches that were cut down for firewood and charcoal every 15 to 20 years. Many plant and animal species are able to live in these deciduous forests because of traditional management practices.

In recent decades, population decline in villages has led to the disappearance of satoyama from the Japanese landscape. Ownership patterns have also been a factor. Shared ownership of satoyama forests near villages has been common since the beginning of the 19th century. These forests were logged for economic considerations and the construction of houses. Because forests near villages have been cut down, old-growth forests today are often located far from villages. A number of golf courses are developed in Satoyama throughout Japan.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Government of Japan

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, Daily Yomiuri, Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2025