EARLIEST PEOPLE IN ACEH

Archaeological evidence indicates that the earliest inhabitants of Aceh date to the Pleistocene period. These populations lived along the west coast of Aceh, particularly in the regions of present-day Langsa and Aceh Tamiang, and displayed Australomelanesoid physical characteristics. Their subsistence relied heavily on marine resources, especially shellfish, supplemented by terrestrial animals. They are known to have used fire and to have practiced ritual burial.

Later migrations shaped the ancestry of Aceh’s indigenous population. Early groups identified as Proto-Malay peoples, including the Mantr and Lhan, were followed by Deutero-Malay populations such as the Cham, Malay, and Minangkabau. Together, these groups formed the core pribumi population of Aceh.

Acehnese ancestry was further enriched by foreign peoples, particularly Indians, as well as smaller numbers of Arabs, Persians, Turks, and Portuguese. Aceh’s strategic position at the northern tip of Sumatra for millennia made it a focal point of maritime trade and a center for interaction and intermarriage among peoples engaged in sea routes linking the Middle East, South Asia, and China.

Chinese and Indian sources dating from around A.D. 500 onward refer to a settlement in northern Sumatra known as P’o-lu, which many scholars identify with an area near present-day Banda Aceh. These accounts note that ordinary inhabitants wore cotton clothing, while the elite dressed in silk, and Chinese annals describe the local population as Buddhist at that time.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ACEH: GEOGRAPHY, POPULATION, GOVERMENT, RESOURCES factsanddetails.com

ACEH INSURGENCY: GRIEVANCES, GAM, FIGHTING, PEACE factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE: RELIGION, LANGUAGE, POPULATION, ORIGINS factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, WOMEN factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE LIFE: VILLAGES, CUSTOMS, FOOD, CANNABIS factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE CULTURE: CLOTHES, FOLKLORE, WEAPONS, DANCES factsanddetails.com

ACEH TRAVEL: BANDA ACEH, BEACHES, HIGHLANDS, SIGHTS factsanddetails.com

DECEMBER 2004 TSUNAMI IN INDONESIA: DAMAGE, VICTIMS AND SURVIVOR STORIES factsanddetails.com

RELIEF AND REBUILDING AFTER THE 2004 TSUNAMI IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

SHARIA IN ACEH factsanddetails.com

Early History of Religion in Aceh

Situated at the northernmost tip of Sumatra, Aceh has been the Indonesian region most directly exposed to influences from the Islamic Middle East and Islamized India. This long history of contact is even reflected in the physical appearance of many coastal Acehnese, among whom Arab and Indian features are common. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Acehnese were for a period partially influenced by Hindu culture, a legacy reflected in their traditions and in the many Sanskrit loanwords found in the Acehnese language. Sustained trade with the Islamic world eventually led to the Islamization of the population, gradually displacing earlier religious systems. As a result, the Acehnese have been Muslim for many centuries.

The Acehnese historically played a central role in trade networks linking India and China. Their closest linguistic relatives are the Cham of central Vietnam, and their shared stock of Austroasiatic (Mon–Khmer) loanwords points to close early contacts among related communities. These connections suggest the existence of an early network of kindred groups stretching from Vietnam to Sumatra via the Malay Peninsula, particularly during the period when trade routes crossed the Isthmus of Kra rather than circumnavigating the peninsula.

Rise of Aceh

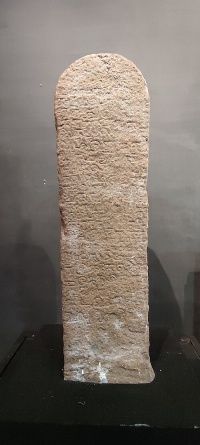

Aceh came into contact with the wider world as early as the A.D. sixth century. Chinese chronicles from this period refer to a kingdom at the northern tip of Sumatra known as Po-li. The region is also mentioned in several Arabic writings from the early ninth century, as well as in inscriptions discovered in India, indicating its early integration into international trade networks.

The most prominent early polity recorded in the Acehnese region was Samudra—meaning “ocean,” a term from which the name Sumatra is probably derived. Historically, much of Sumatra was more closely connected economically and culturally to the Malay Peninsula than to Java. Early Acehnese rulers are believed to have been Buddhists of Indian origin, reflecting strong South Asian influence.

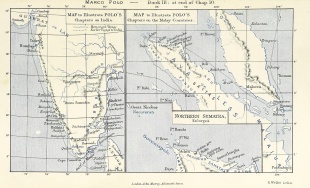

Aceh was among the first regions in Indonesia to engage extensively with foreign peoples. Chinese traders reached the area in the sixth century, followed by Arab merchants in the ninth century. By the ninth and tenth centuries, increasing numbers of Arab and Persian traders were active in the region. Marco Polo also visited Aceh in 1292 during his journey from China to Persia, further attesting to Aceh’s significance within long-distance maritime trade routes.

During the decline of the Srivijaya empire, Malay populations migrated into Aceh, settling particularly in the Tamiang River valley and later becoming known as the Tamiang people. After their conquest by the Samudera Pasai Sultanate in the fourteenth century, they gradually integrated into Acehnese society, though they retained strong cultural and linguistic ties to Malay traditions.

Marco Polo and Ibn Batutta in Aceh

In 1292, Marco Polo, on his voyage from China to Persia visited Sumatra and reported that on the northern part of Sumatra there were as many as six trading ports including Ferlec, Samudera and Lambri. It is ironic that this area is presently one of the least known of Indonesia.

On his journey home from China to Italy in 1291,Marco Polo was forced to spend five months on “Java the Less”—Sumatra—waiting for the monsoon winds to change direction so he could sail to Ceylon and India. His accounts of the island mixed keen observation with sailors’ tales and exaggeration: he described the sago palm, an important staple food,

Marco Polo reported described accurately that cannibals lived in Sumatra but then went on to describe strange beasts, including enormous unicorns, in size “not all by any means less than an elephant.” These were probably Sumatran rhinoceroses. On Sumatra, Polo said: “I tell you quite truly that there are men who have tails more than a palm in size.

Ibn Battuta travel to Sumatra in present-day Aceh around 1345, staying at the Samudra Pasai Sultanate, the easternmost Islamic territory he encountered, where he met its pious Sultan, Al-Malik Al-Zahir. He stayed as a guest of the Sultan for about two weeks, receiving supplies and a ship for his voyage to China. Ibn Battuta described Samudra Pasai as the furthest point of the Islamic world at that time. He noted the ruler's deep piety, his practice of the Shafi'i school of Islamic law, and the Sultan's zeal for fighting non-Muslims.

Ibn Battuta (1304-1369) is regarded as the greatest traveler of all time. He was an Islamic scholar from Tangier in present-day Morocco who traveled 120,000 kilometers (75,000 miles) through more than 40 present-day countries Africa, the Middle East and Asia during a 27 year period 700 years before trains and automobiles. He described his adventures in “Travels in Asia and Africa”. Ibn Battuta was a contemporary of Marco Polo (1254-1324). His journeys preceded those of Columbus by about 150 years. Although he is little known in the West he is as well known as Marco Polo and Columbus in the Arab world.

See Separate Articles: EARLY EUROPEAN EXPLORERS IN INDONESIA: MARCO POLO, NICOLÒ DEI CONTI, MAGELLAN'S CREW factsanddetails.com ; EARLY INDIANS, CHINESE AND ARABS IN INDONESIA: IBN BATTUTA, YIJING, ZHENG HE factsanddetails.com

Islam Reaches Aceh

Islam is believed to have reached Aceh between the seventh and ninth centuries CE through contact with Muslim traders. The earliest Islamic polity in the region was the kingdom of Perlak, traditionally dated to 804 CE. This was followed by the emergence of other Islamic states, including Samudera Pasai in the eleventh century, Tamiah in the late twelfth century, and Aceh in the early thirteenth century. The later Sultanate of Aceh Darussalam, founded in 1511, would become the most powerful successor state.

When Marco Polo visited the region in 1292, Aceh had not yet been fully Islamized. He reported that while some port towns had already converted to Islam, other areas remained non-Muslim. By the time the Samudera Pasai Sultanate was firmly established, however, Islam had become the dominant religion in much of northern Sumatra. By the thirteenth century, it was clearly the major religious force in and around Aceh.

Aceh was the first region in what is now Indonesia to embrace Islam and subsequently became a major center for its spread throughout Southeast Asia. Islam reached early polities such as Fansur and Lamuri by around 1250 CE. By 1323, when the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta passed through Pasai, the region was fully Muslim, and Pasai had become a model Islamic court in the archipelago. Nearby, however, several independent states—such as Barus, Daya, Lamri, and Aru—continued to exist alongside it.

By the sixteenth century, Aceh had emerged as one of Southeast Asia’s most important Islamic cultural and scholarly centers, exerting wide religious and intellectual influence across the region.

Kingdom of Aceh (16th-19th Centuries)

In the territory of Lamri, Sultan Ali Mughayat Shah founded the Sultanate of Aceh at the beginning of the sixteenth century. The new state quickly benefited from the Portuguese conquest of Melaka in 1511, as displaced Muslim merchants—followed later by Protestant Dutch and English traders—redirected their commercial activities to Aceh. From the outset, Aceh emerged as a major contender for control of trade in the Malacca Strait. [Source: Wikipedia, Library of Congress. A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Aceh’s first sultan ruled over a harbor-centered polity that openly challenged Melaka’s dominance of regional trade. In 1585, to mark a trade agreement with England, the Acehnese court sent a message to Queen Elizabeth I proclaiming the sultan as “the mighty ruler of the regions below the wind,” whose authority stretched from sunrise to sunset. By the seventeenth century, Aceh commanded formidable military resources, including large galleys with crews of up to 800 men, cavalry mounted on Persian horses, elephant corps, and conscripted armies. From this position of strength, Aceh became deeply involved in commercial rivalries and political intrigues with the Portuguese, Dutch, and English.

Aceh’s rise culminated in what is often described as its Golden Age, particularly during the reign of Sultan Iskandar Muda (r. 1607–1636). In the early seventeenth century, the Sultanate of Aceh was the wealthiest, most powerful, and most cultivated state in the Malacca Straits region. Acehnese ships carried pepper to ports in the Red Sea, supplying as much as half of Europe’s demand. Acehnese influence extended far down Sumatra, where royal viceroys governed the Minangkabau, Simalungan Batak, and Karo Batak regions, and across the Malay Peninsula, bringing Kedah, Perak, Johor, and Pahang under Acehnese sway.

Although Aceh’s rulers were often committed to promoting Islam, the sultanate’s major military campaigns were driven more by commercial competition than by religious motives and were directed against Muslim as well as Christian rivals. Under Iskandar Muda, Aceh pursued an aggressive foreign policy and a highly centralized, increasingly authoritarian system of rule. The sultan attempted to impose royal monopolies, intervened directly in the trading activities and private property of the orang kaya (wealthy elites), and invested heavily in massive, heavily armed warships of innovative design. One such vessel, aptly named Terror of the Universe, reportedly exceeded 90 meters in length and carried more than 700 men. Iskandar Muda also skillfully played European and Asian powers against one another to advance Aceh’s interests.

The harshness of Iskandar Muda’s rule, however, created deep internal opposition and nearly provoked civil war. The economic gains of his reign proved temporary, and the orang kaya eventually reasserted themselves, working to limit royal authority. From the late seventeenth century, they successfully promoted a succession of female rulers, perhaps believing them to be more moderate or more easily controlled.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the influence of both the court and the orang kaya declined as hereditary district chiefs (uleëbalang) and Muslim religious leaders gained prominence. As a result, Aceh lost much of its imperial reach and political cohesion. Nevertheless, unlike most contemporary regional states, Aceh remained an important local power and a significant economic force, producing more than half of the world’s pepper supply as late as around 1820. Although Aceh allied with Dutch forces in the capture of Portuguese Melaka in 1641, it largely avoided entanglement with the Dutch East India Company thereafter and retained its independence until the late nineteenth century.

Aceh During the Colonial Period

The Portuguese capture of Melaka in 1511 greatly benefited the emerging kingdom of Aceh. Many Asian and Arab merchants, seeking to avoid Portuguese-controlled waters, redirected their trade to Aceh’s port, bringing new wealth and prosperity. Muslim traders—followed later by Protestant Dutch and English merchants—found refuge there, while Aceh launched a prolonged holy war against Melaka’s new Catholic rulers that lasted roughly from 1540 to 1630. During this period, Aceh established its dominance in trade and politics across northern Sumatra, reaching its height between about 1610 and 1640. [Source: Wikipedia, Library of Congress. A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Acehnese power began to wane after a major naval defeat in 1629, when an armada sent to capture Melaka was destroyed. The decline accelerated following the death of Sultan Iskandar Thani in 1641. Prolonged and often violent succession struggles weakened central authority and led the Acehnese aristocracy to accept a succession of female rulers in the seventeenth century, despite prevailing Islamic norms favoring male leadership. As royal power diminished, local lords known as uleëbalang, who controlled river mouths and interior trade routes, grew increasingly influential.

The decentralization of political power did not immediately undermine Aceh’s economic vitality. On the contrary, Aceh remained wealthy, particularly through its pepper trade, which attracted the attention—and occasionally the aggression—of foreign powers, including American and French interests in the 1820s and 1830s. A mutual defense treaty with Britain initially deterred Dutch intervention, and the Netherlands did not launch a major invasion until after the treaty lapsed in 1871.

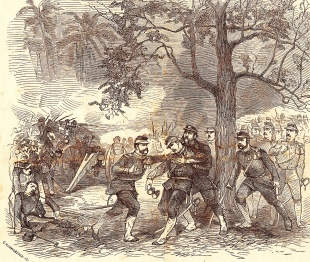

European rivalry intensified in the nineteenth century. Under the 1824 London Treaty, Britain ceded its possessions in Sumatra to the Netherlands in exchange for Dutch withdrawal from British-controlled territories and the abandonment of claims on Singapore. After Britain withdrew its protection in 1873, the Dutch moved to conquer Aceh, triggering the Aceh War. Fought intermittently from 1873 into the early twentieth century, this conflict became the longest and most costly war in Dutch colonial history, claiming more than 10,000 Dutch lives and vast financial resources.

Although the Dutch declared victory after decades of fighting, Aceh was never fully subdued. Following a partial surrender in 1903, the region came under nominal Dutch administration by 1918, yet resistance persisted. Aceh was incorporated into the Republic of Indonesia in 1946 and continued to exercise a significant degree of local autonomy until the early 1960s. The long struggle against foreign domination left a deep imprint on Acehnese identity, fostering a strong sense of independence, religious devotion, and moral discipline—traits that continue to shape Acehnese society despite the gradual opening brought by modernization and industrialization.

Aceh After Indonesia’s Independence

During World War II, from 1942–1945, Aceh was occupied by Japanese forces. In August 1945, Indonesia proclaimed independence from the Netherlands. Acehnese leaders and fighters played a prominent role in the anti-colonial struggle, contributing men, resources, and strategic support. When Indonesia achieved formal sovereignty in December 1949, Aceh agreed to become part of the new republic—largely on the understanding that it would receive special autonomy in recognition of its contributions.

Initially, Aceh enjoyed a degree of self-rule. However, the government in Jakarta soon moved toward greater centralization under a “unitary state” model, undermining earlier promises. In August 1950, Aceh’s special status was revoked and the region was incorporated into the province of North Sumatra. This decision, particularly resented because it placed Aceh within a province dominated by Christian Batak populations, triggered widespread unrest.

In 1953, under the leadership of Daud Beureueh, Acehnese rebels joined the Darul Islam movement, declaring an independent Islamic state. The rebellion lasted nearly a decade. In an effort to pacify the region, Jakarta reversed the 1950 incorporation in 1957, and in 1959 Aceh was designated a “Special Region” (Daerah Istimewa), granting autonomy over religion, education, and customary law. In practice, however, many of these promises were only partially implemented, leaving dissatisfaction unresolved.

Aceh Under Suharto (1996-1998): Natural Gas, Exploitation, Discontent

Following General Suharto’s seizure of power in 1966, Indonesia entered the era of the “New Order.” The regime relied heavily on the military as the dominant institution in political, social, and economic life under the doctrine of dwifungsi (dual function). Across Indonesia, hundreds of thousands of people accused of communist sympathies were killed. The Indonesian Revolution had already taken a particularly violent form in Aceh, where ulama mobilized popular forces against the traditional aristocracy (uleëbalang), who were largely eliminated as a class. Under the New Order, grievances deepened as economic exploitation combined with political repression.

In Aceh, Suharto’s government exploited the region’s abundant natural resources—particularly natural gas, petroleum, gold, and other minerals—while providing little benefit to the rural population. Aceh’s natural resources have been mostly exploited for the benefit of foreign companies and Jakarta’s elites. Aceh has only received about 5 percent of the oil and gas profits.

Natural gas deposits were discovered in Aceh in the early 1970s. The Arun fields account for about one-third of Indonesia’s liquid natural gas (LNG) production and have helped Indonesia become the world’s largest LNG exporter. However, the land of the local population was expropriated without compensation, pushing many into poverty. Mobil operates the Arun facilities in partnership with Indonesia’s state oil company, Pertamina, and a Japanese company. Mobil obtained the contract through kickbacks to the Suharto family (Mobil merged into ExxonMobil in November 1999). Mobil’s contract stipulates that Indonesian soldiers provide security for the facility. Some 5,000 soldiers are effectively on the company payroll. Human rights groups claim that the company is complicit in the killings, beatings, and rapes carried out by these forces against civilians, particularly in the 1990s.

Discontent gave rise to the Free Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, GAM), which launched an armed separatist rebellion demanding greater control over local resources and the protection of Acehnese identity. The government responded with harsh military measures. In 1989, Aceh was placed under martial law, ushering in a period marked by widespread human rights abuses.

Aceh Insurgency

Modern separatism in Aceh coalesced around the Free Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, GAM), which emerged in response to the policies of Suharto’s New Order regime (1966–1998). Despite Aceh’s designation as a “Special Region,” Jakarta tightly controlled the province and exploited its rich natural resources—including natural gas, petroleum, gold, silver, and copper—while the rural population saw few benefits. These grievances sparked GAM’s armed rebellion in the late 1970s. By 1979, the initial uprising was crushed; mass arrests followed, and GAM’s founder, Hasan di Tiro, along with other leaders, fled into exile in Sweden.

The rebellion re-emerged more forcefully in the late 1980s. In 1989, Aceh was declared a Military Operations Area (Daerah Operasi Militer, DOM), effectively placing the province under martial law. Jakarta doubled troop deployments to roughly 12,000 soldiers, and by early 1992 GAM had been largely suppressed. The military campaign, however, was marked by widespread human rights abuses against civilians. Between 1989 and 1998, an estimated 9,000 to 12,000 people were killed, and thousands more were displaced within Aceh or forced to flee to neighboring provinces.

Following the fall of Suharto in 1998, Acehnese mobilization intensified as demands for autonomy resurfaced. The post–New Order period was marked by repeated shifts in Jakarta’s policy, alternating between concessions of greater autonomy and renewed military offensives against GAM insurgents, prolonging instability well into the late twentieth century. A peace deal was finally hammered out of Aceh was devastated by the December 2004 tsunami.

See Separate Article: ACEH INSURGENCY: GRIEVANCES, GAM, FIGHTING, PEACE factsanddetails.com

December 2004 Tsunami in Aceh

The December 26, 2004 tsunami devastated coastal areas in Aceh, Indonesia's northernmost province. Banda Aceh and other cities on the west coat of Aceh resembled Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. When the waters receded, dead bodies were left in people's yards. Rice cookers were deposited on the roofs of houses. Cars were left in trees. In Aceh land that once houses 120,000 people was permanently submerged under water.

Around 170,000 people were killed (130,000 confirmed dead, 37,000 missing) in Indonesia, most of them in Aceh province. For a while it was thought around 230,000 people were killed there but in April 2005, the government reduced the number of missing from 95,000 to 37,000. The tsunami left more than 500,000 people homeless and caused an estimated $4.5 billion in losses and damage.

In some towns and neighborhoods in Aceh the death rate reached 90 percent. The village of Lampuuk had 6,500 residents before the disaster and only 700 afterwards. Fewer than 20 of the survivors were women. Calang had 7,300 people before the tsunami and 750 afterwards. The only building left standing was a large, white mosque. There wasn't even much debris. Everything was swept away. In the next village to the south, Kreung Sabe, half the 4,000 people that lived there were killed and all but 500 were left homeless. Further south still in Panga not a single house was left standing and around 800 of the 1,100 people that lived there were killed.

The most powerful waves from the tsunami struck Meulaboh, a city of 70,000 on the west coast of Aceh, 170 kilometers southeast of Banda Aceh. It was the closest city to the epicenter of the earthquake and was devastated by both the earthquakes and the tsunami. The waves reached three kilometers inland. Tens of thousands died. But the nearness to the earthquake is believed to have saved many people who were driven out of their homes by the quake and heeded warning to run to high ground when people saw the wave approaching. Many of the dead were children, who couldn't swim or weren't strong enough to escape when water engulfed them.

Bodies were strewn in the streets, rotting in the tropical sun and producing a horrible stench. Many were dumped in mass graves, sometimes 60 at a time with bulldozers, without a ceremony or funeral rites. This added insult to injury of the disaster to the largely devout Acehese who were distressed to see their relatives denied a proper Muslim burial. At first many bodies were left unburied because local people wanted them to have a proper Muslim burial. They were then buried en mass after a Muslim cleric in Jakarta issued a fatwa, declaring in a time of crisis it was okay to bury people without proper rites.

A year after the disaster an iman at a mosque in Ulee Lheue in Aceh told worshippers that the tsunami was a religious warning. “Please forgive the people who have left us for their wrongdoing," he said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025