ACEHNESE

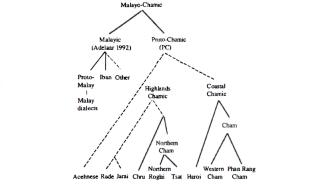

The Acehnese (pronunced AH-cheh-neez) are the main ethnic group in Aceh, the westernmost province of Indonesia, on the northernmost tip of Sumatra. Also known as the Achehnese, Acinese, Lam Muri, Lambri, Akhir, Achin, Asji, A-tse, Atse, Atchinese, Atjehnese, Ureung Aceh, Ureung Baroh and Ureung Tunong, they are wekk-known in Indonesia for their devotion to Islam, their militant resistance to colonial and republican rule, and their tragic experience as victims of the December 26, 2004 tsunami. The Austronesian language they speak — Acehnese — belongs to the Aceh–Chamic group of Malayo-Polynesian of the Austronesian language family. It is related to other Indonesian languages but most closely resembled the Cham languages of Indochina. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Aceh do consider themselves to be ethnically or religiously distinct form other Muslim Indonesians. Before Indonesia became independent Aceh was a semi-autonomous sultanate that made it own trade agreements and battled the Dutch. They honor heroes who fought for Indonesian independence. Although the Acehnese were renowned throughout the nineteenth century for their pepper plantations, most are now rice growers in the coastal regions. [Source: Library of Congress]

The vast majority of Acehnese people are Sunni Muslims. They have have traditionally been agriculturists, metalworkers, and weavers. Their social organization is communal and matrilocal. They live in villages, or gampôns, which combine to form districts known as mukims. The golden era of Acehnese culture began in the 16th century with the rise of the Islamic Aceh Sultanate, reaching its peak in the 17th century.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ACEH: GEOGRAPHY, POPULATION, GOVERMENT, RESOURCES factsanddetails.com

ACEH HISTORY: TRADE, ISLAM, KINGDOMS, ESCAPING COLONIALISM factsanddetails.com

ACEH INSURGENCY: GRIEVANCES, GAM, FIGHTING, PEACE factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, WOMEN factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE LIFE: VILLAGES, CUSTOMS, FOOD, CANNABIS factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE CULTURE: CLOTHES, FOLKLORE, WEAPONS, DANCES factsanddetails.com

ACEH TRAVEL: BANDA ACEH, BEACHES, HIGHLANDS, SIGHTS factsanddetails.com

DECEMBER 2004 TSUNAMI IN INDONESIA: DAMAGE, VICTIMS AND SURVIVOR STORIES factsanddetails.com

RELIEF AND REBUILDING AFTER THE 2004 TSUNAMI IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

SHARIA IN ACEH factsanddetails.com

Acehnese Population

The Acehnese population is primarily located in Indonesia's Aceh province and numbers around 4 million to 4.2 million people, accounting for approximately 70 percent of the people in Aceh. The Acehnese people inhabit coastal lands along the northernmost end of Sumatra, as well as river valleys leading into the interior (the high mountains and thick forests of the interior are the home of another ethnicity, the Batak-related Gayo people). In west and south Aceh, Acehnese have intermingled with people from West Sumatra, as reflected in their language, designs, and customs. The people in Aceh tend to be taller than those found elsewhere in Indonesia.

The Acehnese are divided into two main groups: 1) the hill people, regarded by anthropologist as homogenous proto-Malays; and 2) lowland coastal people, who have mixed more with other groups such as Arabs, Tamils, Chinese, indigenous groups and other Indonesian groups. In the 2000s, Acehnese comprised 50 to 70 percent of the population of the Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam, or 2–3 million people. At that time Banda Aceh had only 80,000 inhabitants and the majority of Acehnese lived in small towns in the fertile coastal plain, mostly on 600-kilometers (375-miles) road between Banda Aceh and Medan in neighboring North Sumatra province,

There are three major ethnic groups in Aceh; Acehnese, Gayo and Alas.. . The Gayo and Alas tribes are smaller groups that inhabit the highlands of Aceh. The Gayo live in central Aceh, and the Alas live in southeastern Aceh. The high mountains and thick forests of the interior are the home pf the Batak-related Gayo people. Among the other non-Acehnese ethnic groups are the Miangkabau on the west coast; the Klueton in the south; and Javanese and Chinese throughout the province.

Acehnese Language

The Acehnese language is related to Malay but is more closely affiliated with the Chamic languages of central Vietnam. It belongs to the Chamic branch of the Malayo-Polynesian subgroup within the Austronesian language family. Closely related languages include Cham, Roglai, Jarai, Rade, Chru, and Tsat, spoken today in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Hainan. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

Acehnese vocabulary contains a core of basic words borrowed from Austroasiatic (Mon–Khmer) languages such as Khmer, Mon, and Vietnamese. Many of these loanwords entered the language at the Proto-Chamic stage and are shared with other Chamic languages, while others are unique to Acehnese. The latter suggest that the ancestors of the Acehnese may have resided for a time in the Malay Peninsula or southern Thailand, where they were in contact with Mon–Khmer–speaking populations before migrating to Sumatra. Over the centuries, Acehnese has also absorbed substantial lexical influence from Sanskrit and Arabic, particularly in the domains of religion, law, governance, warfare, and learning, as well as extensive borrowing from Malay. Until the seventeenth century, Malay written in Arabic script served as the sole literary language of Aceh. From the seventeenth century onward, Acehnese began to be used as a written medium in its own right.

Historically, speakers of Chamic languages initially controlled only a small area around present-day Banda Aceh in Aceh Besar. Marco Polo noted in 1292 that Aceh consisted of eight small kingdoms, each with its own language. Over the following four centuries, the expansion of Banda Aceh’s political power—particularly over coastal polities such as Pidie, Pasai, and Daya—and the gradual absorption of their populations led to the dominance of Acehnese along the coast. Speakers of other indigenous languages were increasingly pushed into the interior as Acehnese-speaking populations expanded agricultural land.

Dialects of Acehnese in the Aceh Besar valley fall into two major groups: the Tunong dialects of the highlands and the Baroh dialects of the lowlands. The diversity of dialects in Aceh Besar and Daya suggests long-standing settlement in these regions. Pidie Regency also exhibits significant dialect variation, though less than Aceh Besar and Daya. By contrast, dialects along the eastern coast of Pidie and in southern Daya are relatively homogeneous, a pattern associated with population movements accompanying the territorial expansion of the Aceh Sultanate after the sixteenth century.

Origin of the Acehnese

The pribumi population of Aceh emerged through successive migrations of indigenous groups. Early Proto-Malay peoples, including the Mantr and Lhan, were followed by later Deutero-Malay arrivals such as the Cham, Malay, and Minangkabau, together forming the core of Aceh’s indigenous population. [Source: Wikipedia]

Linguist Paul Sidwell has argued that during an early phase of linguistic change—possibly before the beginning of the Common Era—the Chamic-speaking ancestors of the Acehnese left the mainland and eventually settled in northern Sumatra. Drawing on Graham Thurgood’s work, Sidwell suggests that Acehnese speakers had already separated from other Chamic-speaking populations by the first or second century BCE. The resulting geographic isolation between Acehnese and other Chamic languages may explain the later influence of Malay, Khmer, Thai, and Vietnamese on Chamic languages in Indochina over the following two millennia.

Acehnese oral traditions likewise trace the earliest inhabitants of the region to indigenous groups such as the Mante and Lhan. The Mante are described as a native population related to the Batak, Gayo, and Alas peoples, while the Lhan are said to be connected to the Semang groups who migrated from the Malay Peninsula or Indochina, particularly from Champa and Burma. According to tradition, the Mante initially settled in what is now Aceh Besar before gradually spreading to other parts of the region.

History of the Acehnese

Aceh came into contact with the wider world as early as the A.D. sixth century. Chinese chronicles from this period refer to a kingdom at the northern tip of Sumatra known as Po-li. The region is also mentioned in several Arabic writings from the early ninth century, as well as in inscriptions discovered in India, indicating its early integration into international trade networks. In 1292, Marco Polo, on his voyage from China to Persia visited Sumatra and reported that on the northern part of Sumatra there were as many as six trading ports including Ferlec, Samudera and Lambri. It is ironic that this area is presently one of the least known of Indonesia.

Islam is believed to have reached Aceh between the seventh and ninth centuries CE through contact with Muslim traders. The earliest Islamic polity in the region was the kingdom of Perlak, traditionally dated to 804 CE. This was followed by the emergence of other Islamic states, including Samudera Pasai in the eleventh century, Tamiah in the late twelfth century, and Aceh in the early thirteenth century. The later Sultanate of Aceh Darussalam, founded in 1511, would become the most powerful successor state.

Aceh’s rise culminated in what is often described as its Golden Age, particularly during the reign of Sultan Iskandar Muda (r. 1607–1636). In the early seventeenth century, the Sultanate of Aceh was the wealthiest, most powerful, and most cultivated state in the Malacca Straits region. Acehnese ships carried pepper to ports in the Red Sea, supplying as much as half of Europe’s demand. Acehnese influence extended far down Sumatra, where royal viceroys governed the Minangkabau, Simalungan Batak, and Karo Batak regions, and across the Malay Peninsula, bringing Kedah, Perak, Johor, and Pahang under Acehnese sway.

Acehnese power began to wane after a major naval defeat in 1629, when an armada sent to capture Melaka was destroyed. The decline accelerated following the death of Sultan Iskandar Thani in 1641. A decentralization of political power in Aceh after this did not immediately undermine Aceh’s economic vitality. On the contrary, Aceh remained wealthy, particularly through its pepper trade, which attracted the attention—and occasionally the aggression—of foreign powers, including American and French interests in the 1820s and 1830s. A mutual defense treaty with Britain initially deterred Dutch intervention, and the Netherlands did not launch a major invasion until after the treaty lapsed in 1871.

Aceh was never fully subdued by the Dutch. Following a partial surrender in 1903, the region came under nominal Dutch administration by 1918, yet resistance persisted. Aceh was incorporated into the Republic of Indonesia in 1946 and continued to exercise a significant degree of local autonomy until the early 1960s.

See Separate Article: ACEH: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

Religion and Islam in Aceh

The Acehnese are regarded as the most devout Muslims in Indonesia. They take their religion, their manners and their morals very seriously, and put particularly emphasis in making the pilgrimage to Mecca, giving to the poor and fasting during Ramadan. The Acehnese have called their homeland the “Porch of Mecca” and have traditionally regarded their piety as setting them apart from other Indonesians. Christians and Buddhists make up only a small portion of the total population.

Most Acehnese are Sunni Muslims of the with Shafi'i school, known for synthesizing traditional hadith (Prophet's sayings) with rational methods like analogy (Qiyas), prioritizing the Quran, Hadith, scholarly consensus (Ijma), and analogy for deriving Islamic law (Fiqh), and is widely followed in Southeast Asia.. Modernist Muslims, particularly followers of Muhammadiyah, do not perform the post-funeral prayers commonly observed by other Acehnese Muslims.

Not everyone is Muslim. The religious makeup of the region also includes Protestants (1.32 percent), Roman Catholics (0.16 percent), Hindus (0.02 percent), and Buddhists (0.37 percent). Although the Acehnese are very devout and are often called fanatics by other Indonesians it is said they can also be open-minded and understanding toward the religious needs of others. Churches and temples are always found in Aceh towns. In 1990, there were 2,359 mosques, 6,408 meunasah (Muslim houses of worship), 2,955 mushallas (simple places of worship), 91 churches/schools, and six Buddhist temples.

Religion and Traditional Beliefs in Aceh

Traditional beliefs in Aceh persist alongside Islam, particularly the belief in spirits that inhabit trees, rocks, and stones. Ghosts and malevolent spirits are thought to be especially active at dusk, and people often consult dukun—spirit healers or shamans—for protection and guidance. Many aspects of agriculture continue to be governed by pre-Islamic rituals and it is widely believed that magic can play a role in healing and ensure success in agriculture and other endeavors. .

Traditional beliefs also endure in forms of female shamanism, which has a long tradition in Aceh, and everyday superstition. It is customary to cleanse places where blood has been spilled by lighting a small fire, and some Acehnese dye their hands orange with herbal substances to ward off illness. Ritual meals to bless rice cultivation (kenduri blang) and fishing (kenduri laut) combine local traditions with Islamic elements, including Arabic prayers and the recitation of the Quranic surah Yasin. Dukun are believed to cast spells (sijunde) that can cause illness or death or counteract the spells of others. Healing practices often involve exorcistic rituals intended to “cool” the afflicted person, and dukun also interpret dreams and omens. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Acehnese folklore holds that spirits inhabit forests, swamps, river mouths, and banyan trees. The jen aphui is a fire spirit that appears as a light at night, while the sibujang itam is a frightening but magically powerful being believed to be enlisted for harmful purposes. The geunteut is described as a giant that presses down on sleeping people. Other spirits include the burong, women who died in childbirth and appear dressed in white with unnaturally long fingernails, and the burong tujuh, seven sister spirits said to threaten women during childbirth.

Islamic Lifestyle in Aceh

Many Acehnese regard themselves as devoutly Muslim but not Islamists. Alcohol is banned. Children are sent to Islamic schools and money is collected for mosques. Sharia (Islamic law) has been implemented and to a limited degree is the law of the land. There are no stoning or amputations but public flogging — which has its roots more in European than Muslim practcies — has been carried out. There have also been stories about Western women being harassed for wearing shorts and western men getting disemboweled with a dagger for flirting with Aceh women.

Sharia shapes nearly every aspect of family and community life in Aceh, including weddings, marital disputes, civil cases, funerals, and inheritance. The lowest-level religious courts often convene after Friday prayers. Acehnese Muslims tend to support national Islamic political organizations, including modernist movements such as Muhammadiyah. The close intertwining of Acehnese culture and Islam is commonly expressed in the saying “adat ngon hukom lagee zat ngon sifeuet,” meaning that Acehnese custom and Islamic law are as inseparable as essence and manifestation.

Boys and girls begin to have religious duties and obligations at the onset of puberty. The Acehnese believe knowledge and understanding of Islam make individuals moral beings capable of distinguishing right from wrong. Religious leaders who teach children (Teungku/Tgk) help them become rational beings. Communion with Allah, it is thought, can only be achieved through daily prayers.

The Acehnese are particularly observant of three of Islam’s five pillars: performing the pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj), paying alms (zakat), and fasting during the month of Ramadan (puasa). Observance of the five daily prayers is less consistent. Pantheistic and mystical traditions remain widespread, and pilgrimages to the graves of renowned Islamic mystics are common.

In some periods, groups of religiously zealous students—sometimes calling themselves the “Taliban,” though operating locally and independently—conduct moral patrols targeting prostitution, theft, and women deemed improperly dressed. Those accused are often publicly reprimanded and, in some cases, forced to march through the streets wearing placards describing their alleged offenses. Punishments for serious crimes are reported, in extreme cases, to include executions.

See Separate Article: SHARIA IN ACEH factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025