ACEH

Aceh (pronounced AH-chay) is the westernmost province of Indonesia and located on the northernmost tip of Sumatra. Home to about 5.5 million people, it contains dense tropical rain forests and jungles, rubber, palm oil and coconut plantations and farms with cocoa trees. It is regarded as the most devoutly Muslim area in Indonesia. It is the closest part of Indonesia to Mecca and the Middle East. It was the place hardest hit by the December 2004 tsunami that killed around 250,000, more than 75 percent of whom were in Aceh.

Aceh's official name has changed over time, but its current official designation is simply Aceh. It was was known as Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam (NAD), meaning "Aceh, Abode of Peace," from 1999 to 2009. Aceh is known today for it strict form of sharia (Islamic law) that includes public flogging and severe punishments for homosexuality. It is also known in Indonesia as the "Verandah of Mecca" because it is where Islam first took hold in the vast archipelago centuries ago. Visitors to the region are advised to be respectful to Muslim customs, Both men and women should keep their legs and arms covered. Women should cover their hair. Alcohol is very difficult to get except at the top end hotels and Chinese restaurants.

There are about 5.5 million people in Aceh (as of the mid 2020s) and ten indigenous ethnic groups have been counted. There are three major ethnic groups in Aceh; Acehnese, Gayo and Alas. Acehnese are the largest group and inhabit the region's coastal areas. In west and south Aceh, however, they intermingled with people from West Sumatra, as reflected in their language, designs, and customs. The Gayo and Alas tribes are smaller groups that inhabit the highlands of Aceh. The Gayo live in central Aceh, and the Alas live in southeastern Aceh.

The Acehnese account for approximately 70 percent of the region's population. They inhabit coastal lands along the northernmost end of Sumatra, as well as river valleys leading into the interior (the high mountains and thick forests of the interior are the home of another ethnicity — the Batak-related Gayo people. Among the other non-Acehnese ethnic groups are the Miangkabau on the west coast; the Klueton in the south; and Javanese and Chinese throughout the province. The people in Aceh tend to be taller than those found elsewhere in Indonesia.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ACEH HISTORY: TRADE, ISLAM, KINGDOMS, ESCAPING COLONIALISM factsanddetails.com

ACEH INSURGENCY: GRIEVANCES, GAM, FIGHTING, PEACE factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE: RELIGION, LANGUAGE, POPULATION, ORIGINS factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, WOMEN factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE LIFE: VILLAGES, CUSTOMS, FOOD, CANNABIS factsanddetails.com

ACEHNESE CULTURE: CLOTHES, FOLKLORE, WEAPONS, DANCES factsanddetails.com

ACEH TRAVEL: BANDA ACEH, BEACHES, HIGHLANDS, SIGHTS factsanddetails.com

DECEMBER 2004 TSUNAMI IN INDONESIA: DAMAGE, VICTIMS AND SURVIVOR STORIES factsanddetails.com

RELIEF AND REBUILDING AFTER THE 2004 TSUNAMI IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

SHARIA IN ACEH factsanddetails.com

Aceh Physical Geography

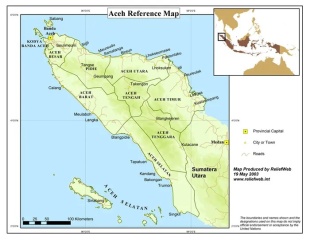

Aceh is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west and the Strait of Malacca to the northeast. It borders the province of North Sumatra to the east, its only land border, and shares maritime borders with Malaysia and Thailand to the east, and Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India to the north. Aceh covers 56,839 squate kilometers (21,945 squate miles) which is comparable to Croatia, Togo and, the U.S. state of West Virginia.

Aceh's topography is predominantly mountainous, dominated by the Barisan Mountains with high peaks like Mount Leuser (over 3,300 meters) in the south, sloping down to a fertile, wide coastal plain along the Indian Ocean and Strait of Malacca, characterized by short, fast rivers and some undulating, hilly terrain, creating diverse landscapes from highlands to low-lying areas. Banda Aceh, the provincial capital, sits on a low-lying coastal plain with an average elevation of about five meters, and is prone to flooding.

The terrain transitions from steep slopes in the highlands to rolling hills and flatter lowlands, with varying soil types. The backbone of Aceh is mountainous, with significant elevations, particularly towards the south and central regions. A broad coastal plain extends along much of the region, particularly in the north, with elevations near sea level. Short, swift rivers flow from the mountains to the sea, often with little value for shipping but shaping the landscape. Aceh is near the Sumatran fault zone, which is why it sso prone to tsunamis and earthquakes.

Government of Aceh

Aceh is a special territory (daerah istimewa) of Indonesia not a province and is more independent and has autonomy than the provinces of Indonesia. Aceh is the only Indonesian province officially practicing Islamic Sharia law. It holds special autonomous status within Indonesia and has been granted special authorities to regulate and manage its own governmental affairs and local interests in accordance with Indonesian laws and regulations.

Aceh's high degree of self-governance allows it to regulate many of its own affairs while remaining part of the Indonesian republic. The province is led by a locally elected governor and a provincial parliament (DPRA), with additional local councils (DPRK) at the city and regency level. Aceh’s political system incorporates indigenous institutions and local traditions alongside national governance structures.

Aceh is the only political unit in Indonesia that officially implements Islamic law (Sharia) through local regulations known as qanun. Sharia influences criminal, economic, social, and political life, and applies primarily to Muslims. The legal system operates on a dual basis, combining Indonesia’s national courts with specialized Aceh Sharia Courts, which handle matters falling under Islamic law.

A distinctive feature of Aceh’s autonomy is the legal recognition of local political parties, which do not exist elsewhere in Indonesia. These indigenous parties emerged from the peace process and play a central role in safeguarding Acehnese cultural and political interests. Their presence reflects Aceh’s effort to balance local identity with participation in the national political framework.

Aceh’s special status originated from the 2005 Helsinki Memorandum of Understanding, which ended decades of armed conflict between the Indonesian government and the Free Aceh Movement (GAM). The agreement laid the foundation for expanded autonomy, political inclusion, and local governance reforms.

Acehnese Government in the Past

Under the Acehnese sultanate, political organization followed a hierarchical structure. Several gampong (villages), each led by a keusyik (or geucik), were grouped into a mukim under the authority of an imeum. Multiple mukim fell under the jurisdiction of an uleebalang (a hereditary regional lord), or, in the capital region, were organized into one of three sagoe, each led by a panglima, often a relative of the sultan. Although the title imeum originally referred to the head of a mosque, some officeholders gradually accumulated secular authority and were formally recognized by the sultan as uleebalang. The uleebalang appointed and could dismiss keusyik, who were responsible for village security, prosperity, and dispute resolution. Each village also included a teungku, responsible for Islamic instruction and ritual life at the meunasah; ureung tua, an elected village council; and a tuha peut, an authority on customary law (adat). Of this traditional structure, only the gampong and mukim continue to function within the modern Indonesian administrative system. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Since Indonesia became independent, Aceh has been ruled by a civilian governor. In the 2000s, Governor Abdullah Puteh was accused of wasting money on expensive projects which are believed to have been tainted by corruption. In One case, an airline he inaugurated at great expense collapsed six months after it was launched. Much of the money is believed to have ended op in his pockets. During this time, There was only one mental hospital for all of Aceh province. Most of its patients were schizophrenics. Electric shock treatment was used.

Before Aceh achieved semi-independence voter turnout was usually low, less than 10 percent. In the 2004 general election, the Free Aceh Movement advised people to vote to avoid reprisals from government forces. In the 2000s, the Indonesian government had 55,000 security forces in the Aceh area. They could pretty much do what they wanted: impose martial law, detain suspects indefinitely without charges, censor the press. As part of the offensive in May 2003, all civilians in Aceh were required to get new ID cards.

In the 2000s, Acehnese society maintained a system of sociopolitical organization that largely paralleled Indonesia’s national administrative structure. At the village level, village chiefs (keuchi) regulated family law and oversaw rice cultivation, while elected religious leaders (teungku) adjudicated matters related to Islamic law. These officials worked in coordination with village councils of elders, district-level administrators (mukim)—each associated with a mosque—and regional authorities under an area leader (uleebalang). Historically, the uleebalang wielded considerable power, and their positions were inherited through patrilineal succession.

Aceh Economy

Aceh continues to hold economic and strategic importance for Indonesia, owing both to its natural resources and its location along the Strait of Malacca—one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, through which much of the oil transported from the Middle East to East Asia passes. Aceh is endowed with natural gas, oil, timber, gold, palm oil, and rich marine resources.

During the late 20th century and early 2000s, Aceh was one of Indonesia’s most important energy-producing regions. Natural gas dominated the economy, and multinational companies—most notably ExxonMobil—played a major role. Lhokseumawe, on the east coast of Sumatra, functioned as Aceh’s main industrial and energy hub. The Arun LNG complex, once among the world’s largest liquefied natural gas facilities, was central to Indonesia’s gas exports.

In the post-2000s period, Aceh has increasingly diversified its economy. Agriculture, plantations, and fisheries now play a larger role, supported by special autonomy funds granted to Aceh after the peace settlement. Palm oil remains a key commodity, while rubber production has declined in relative importance. Coastal shrimp farming and small-scale fisheries continue to support local livelihoods.

Aceh is also known for high-quality Arabica coffee, particularly from the Gayo Highlands in Central Aceh, which has gained international recognition and export markets. Tobacco is cultivated in parts of eastern and southern Aceh, though on a more limited scale. The province’s fertile lowlands and uplands support a wide range of tropical fruits, including mangoes, durian, rambutan, avocados, papayas, guavas, and citrus.

Large areas of Aceh remain forested, including protected ecosystems such as the Leuser Ecosystem, one of Southeast Asia’s most important biodiversity zones. Conservation efforts coexist with ongoing challenges related to logging, plantation expansion, and infrastructure development. Overall, since the 2000s Aceh has shifted from heavy dependence on oil and gas toward a more diversified economy based on agriculture, fisheries, plantations, and government transfers, while its strategic maritime position continues to underpin its national importance.

Work Done by Acehnese

The Acehnese have traditionally been subsistence farmers. In the lowlands they cultivate wet rice, while in the highlands they grow dry rice. Other crops include sugarcane, tobacco, rubber, peanuts, coconuts, areca nut, maize, and pepper. Water buffalo are raised for plowing and for meat. Many farmers also maintain fish and shrimp ponds and grow cocoa and coffee as cash crops. Fishing has long been practiced using nets, seines, lines, and traps.

The majority of Acehnese continue to depend on wet-rice agriculture for their livelihood. By some estimates, more than one-third of the population consists of sharecroppers, alongside thousands of agricultural laborers. The Acehnese are also known for their skill in metalworking, particularly in the production and maintenance of weapons and in gold and silver craftsmanship. Women traditionally produce high-quality silk and cotton textiles. Trade plays an important economic role, and young men have long left their villages—often after marriage—to work or trade elsewhere.

Many rice fields are created by reclaiming and sectioning swampland; only some rely on irrigation from rivers or streams. Men, working cooperatively, manage irrigation systems, while women are primarily responsible for planting and weeding. Swidden (shifting-cultivation) fields located farther from villages provide supplementary crops such as dry rice, chilies, papayas, sweet potatoes, and vegetables. In the past, pepper was the principal cash crop; today, coffee—especially from the highlands—has taken on that role. An alternative to farming has traditionally been trade, particularly the marketing of agricultural produce.

Fishing remains another major source of livelihood. Traditionally, pawang guilds—each consisting of a leader and a boat crew—controlled and managed specific stretches of coastline. In addition, Acehnese households keep cattle and water buffalo, selling livestock as far away as Medan. A small dairy industry exists, though it was introduced and has largely remained in the hands of Bengali immigrants.

Oil and Natural Gas in Aceh

In the early 2000s, Aceh was one of Indonesia’s most important energy-producing regions. Natural gas from Aceh accounted for roughly 30 percent of Indonesia’s total gas production, while oil from the province contributed about 13 percent of national output. The centerpiece of this industry was the Arun oil and gas complex, located in a roughly 50-by-10-mile forested area of northern Aceh. At its peak, the Arun fields generated an estimated US$4 million per day, though nearly all of this revenue flowed to the central government in Jakarta. First exploited in the 1970s, the Arun fields gradually matured, and by the early 2000s were nearing depletion, with no comparably large replacement fields yet discovered.

The PT Arun liquefied natural gas (LNG) refinery was once among the most important LNG facilities in the world, producing up to 40 percent of global LNG exports at its height. Ownership was shared between the Indonesian government (about 50 percent), ExxonMobil Indonesia (around 30 percent), and Japan Indonesia LNG (approximately 15 percent). The plant supplied gas primarily to Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Following the decline of gas reserves, prolonged conflict, and the 2005 Helsinki peace agreement between the Indonesian government and GAM, Aceh’s economic structure began to change. ExxonMobil ceased LNG production at Arun, and the facility was later converted into a regasification terminal. While hydrocarbons remain part of Aceh’s economy, their dominance has diminished, and revenues are no longer on the scale seen during the LNG boom years.

As Aceh’s major fields matured, the oil and gas sector entered a period of transition. While production from legacy fields such as Arun and Working Area “B” declined, new efforts focused on revitalizing existing assets and expanding exploration. Companies such as PT Pema Global Energi continued limited production through field optimization, while Triangle Pase Inc. developed onshore gas in the Pase Block, supplying regional markets in North Sumatra. Japan Petroleum Exploration Company (JAPEX) conducted exploration and test drilling in Block A, including the Matang structure, with promising results.

Following Aceh’s special autonomy arrangements, greater regional control over hydrocarbons was established through the Aceh Oil and Gas Management Agency (BPMA), created under special revenue-sharing regulations. BPMA now oversees upstream operations in the province, with the stated aim of ensuring that Aceh derives greater long-term benefit from its natural resources.

More recently, attention has shifted toward attracting new investment, reopening exploration areas, and repurposing infrastructure within the Arun Special Economic Zone (SEZ) to support industrial development. Although Aceh no longer occupies the dominant position it once held in Indonesia’s energy sector, oil and gas remain strategically important, both as a source of regional revenue and as a foundation for broader economic recovery and growth.

Exxon Mobile in Aceh

ExxonMobil was involved in extracting natural gas from the massive Arun field in northern Aceh near Lhokseumawe. The company also operated the large PT Arun natural gas refinery there. The field was such a major source of income that in the early 1990s, when it was run by Mobil, it accounted for nearly one quarter of the company’s total revenues.

ExxonMobil’s fields produced virtually all of the region’s natural gas, and Jakarta typically received about US$1 billion a year in taxes and revenues from the plant. Much of the gas was exported to Japan and South Korea.

ExxonMobil’s natural gas fields and facilities were surrounded by barbed-wire fences and guarded by more than 3,000 Indonesian troops. Company executives and managers were forced to abandon their homes and live in cheap containers for security reasons.

In 2001, ExxonMobil concluded that it was too risky to continue operating in Aceh and suspended production at the Arun facility for four months. The decision followed repeated attacks: company planes were hit by gunfire, facilities were bombed and assaulted, employees were kidnapped, company convoys were attacked, and about 50 vehicles were hijacked. In one incident, a rebel grenade fired at a gas extraction facility caused a large fire. The shutdown cost the Indonesian government an estimated US$350 million in lost revenues and strained relations between ExxonMobil and Jakarta, which was heavily dependent on gas income.

ExxonMobil paid the Indonesian military an estimated US$500,000 per month for security protection. Some of the soldiers assigned to guard company facilities were implicated in human rights abuses. In one case, a farmer was shot to death by soldiers employed to protect ExxonMobil’s operations. Villagers also resented the company because the facilities brought them few benefits; in some instances, people were forced off their land to make room for installations.

ExxonMobil was later sued in a United States court by human rights organizations acting on behalf of Acehnese villagers, who accused the company of complicity in abuses committed by government soldiers. The Bush administration supported ExxonMobil, viewing the company as an important partner in maintaining good relations with the Indonesian government during the international campaign against terrorism.

Cannabis (Marijuana) in Aceh

Although cannabis is illegal in Indonesia, its use remains widespread in Aceh, where it has long been added—quietly and selectively—to traditional curry dishes and even coffee, as well as smoked. In Banda Aceh, roadside food stalls selling gulai daging, a meat-based curry simmering over gas stoves, are easy to find. When asked whether cannabis is used in the dish, most vendors jokingly hold out their wrists as if in handcuffs and deny it. Still, many privately admit the ingredient is sometimes included. The risks, however, are severe. Possession, trafficking, or use of drugs can lead to heavy penalties in Indonesia, including years in prison. One vendor told AFP he only uses fried cannabis seeds for flavor, not the more potent leaves, which are typically sold to buyers outside the province. [Source: Hotli Simanjuntak, The Jakarta Post, July 3 2010; AFP, February 28, 2005]

Cannabis was once openly grown and sold in Aceh, even cultivated in household gardens. That changed in the 1970s, when the crop was outlawed. Since then, Indonesia has enacted some of the world’s harshest drug laws, including the death penalty for traffickers, declaring a national drug “emergency” amid rising methamphetamine use.[Source: Haeril Halim, AFP, February 5, 2020]

The origins of cannabis in Aceh are disputed. Some claim it arrived with Dutch colonists, but local historian Tarmizi Abdul Hamid points to older manuscripts that describe cannabis’s use in medicine, cooking, pest control, and food preservation—without mention of smoking. According to these texts, it was once believed to treat ailments such as baldness and high blood pressure.

Cannabis later became entangled in Aceh’s separatist conflict. Former farmer Fauzan recalls harvesting crops amid gunfire during clashes between rebels and government forces in the early 2000s. In his village near Banda Aceh, he estimates that up to 80 percent of residents once farmed cannabis, creating hidden paths and storage sites to evade authorities.

Yet Aceh’s situation remains complex. Police regularly raid plantations, jail users, and burn confiscated crops—more than 100 tonnes in a single year. At the same time, debates persist: a provincial lawmaker recently proposed legalizing cannabis for pharmaceutical exports, though the idea was swiftly rejected by both his party and the national narcotics agency.

For users like Iqbal, prohibition has only driven cannabis deeper underground. “People just hide it better now—in coffee or noodles,” he said. “It’s impossible to erase ganja from Aceh. Destroy a lab and meth is gone. Burn a ganja field, and it will just grow somewhere else.”

Despite the danger, cannabis has long been intertwined with Acehnese culinary tradition. According to a local journalist, custom dictates that even poor families eat gulai daging at least three times a year: just before Ramadan, at the end of Ramadan, and before the annual pilgrimage season. Cannabis used in cooking, he notes, almost always comes from the hills.

Cannabis Industry in Aceh

Aceh remains one of Indonesia’s major cannabis-producing regions. Vice Governor Muhammad Nazar has acknowledged that the province is a significant distributor of illegal drugs, with cannabis often used as a bargaining commodity to acquire stronger narcotics such as methamphetamine and heroin from other provinces. According to Nazar, dealers need little more than cash to persuade villagers to plant the crop. [Source: Hotli Simanjuntak, The Jakarta Post, July 3 2010; AFP, February 28, 2005]

The largest cannabis production area is Aceh Besar regency, followed by Bireuen, Central Aceh, Southeast Aceh, Southwest Aceh, and North Aceh. Cannabis plantations have been found in Indrapuri. Cannabis grows easily in the region, whether cultivated deliberately or found wild in forested areas.

Law enforcement efforts are extensive. Police regularly seize large quantities of dried cannabis and destroy thousands of hectares of plantations. Joint operations involving police, the National Anti-Drug Agency, and provincial authorities have intensified, with hundreds of tons confiscated annually. Religious leaders have also been enlisted to deliver anti-drug sermons.

Officials worry that the widespread availability of drugs poses a serious threat to Aceh’s younger generation. Authorities have urged farmers to abandon cannabis cultivation in favor of legal crops such as rice and fruit. As Nazar bluntly put it, no farmer, in his experience, has found lasting success growing cannabis. “It’s better,” he said, “to plant rice than cannabis.” “This land is like heaven,” Fauzan, another farmer, said. “Whatever you plant will grow.” Still, fearing arrest, he eventually abandoned the trade and now grows chilies, working with the government to persuade others to switch to legal crops. The effort is difficult in impoverished communities with limited alternatives.

The devastating tsunami of December 2004 destroyed vast areas of farmland and crops along the coast but surprisingly one crop was largely spared it was grown high in the hills beyond the reach of the waves: cannabis. Anwar, a 38-year-old vendor, told AFP he he adds small amounts of cannabis to both coffee and curry. The supply, he said, comes from the surrounding mountains, where crops escaped the tsunami that wiped out an estimated 36,000 hectares of farmland in northern Sumatra. Cannabis, he adds, remains easy to obtain and relatively stable in price.

Abubakar, a 65-year-old food stall worker, says that while many spices became scarce and expensive after the tsunami, cannabis prices remained stable because the crop was largely untouched. He adds that decades of separatist conflict caused more disruption to cannabis cultivation than the tsunami itself, as many growing areas were controlled by the Free Aceh Movement, making travel dangerous.

Cannabis Seizures and Arrests in Aceh

In May 2013, Indonesia’s National Narcotics Agency (BNN), working together with the Aceh police, destroyed 35 hectares of cannabis plantations in Pulo Kemukiman Lamteuba village, Seulimeum district, Aceh Besar regency. The operation was part of an ongoing effort to reduce cannabis cultivation in Aceh and surrounding areas. BNN spokesperson Yessi Weningati said the operation was led by BNN chief Commissioner General Anang Iskandar. It marked the first large-scale destruction of cannabis fields that year. The plantation sites were located about two and a half hours by road from Banda Aceh. Dozens of BNN and provincial police officers uprooted the plants and burned them on site. The raid followed intelligence received roughly a month earlier, which led to a joint investigation beginning on May 3. [Source: Panca Nugraha, The Jakarta Post, May 15 2013; [Source: Nurdin Hasan, Jakarta Globe, January 6, 2014]

In January 2014, Aceh police seized 1.5 tons of cannabis valued at approximately US$123,000 in two separate drug busts in East Aceh and Pidie districts. In East Aceh, police stopped two vehicles suspected of transporting cannabis. When officers attempted to search the cars, the drivers fled, prompting a pursuit. After warning shots failed to stop the vehicles, police fired directly at them. With assistance from local residents, officers intercepted the cars, arresting one suspect who had been wounded by gunfire, while three others escaped. Police recovered 803 kilograms of cannabis wrapped in black plastic.

A day earlier in Pidie, police intercepted a truck carrying 610 kilograms of cannabis after receiving a tip from local residents. Officers dismantled the truck’s container and discovered the drugs hidden in a secret compartment. Two suspects—one from Aceh and one from North Sumatra—were arrested. Both claimed they were acting only as couriers.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025