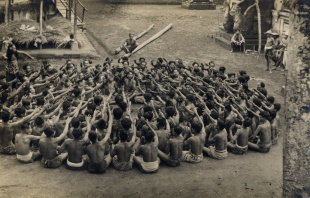

MONKEY DANCE OF BALI (KECAK)

One of the most famous Balinese dances is the Monkey dance, or “Kecak”, which is best seen in front of Pliatan temple. The dance is a visual spectacle. The focus of the dance is a small circular stage that is lit by a fire surrounded by a chorus of bare-chested men imitating the chattering of monkeys. Inside the circle a man and a women act out an episode of the Hindu Ramayana legend in which Rama is helped to by the monkey king and his army to rescue his kidnapped wife Sita from the evil king Rawana. It is now performed mainly for festivals and tourist shows. The moneky dance was reportedly coordinated and choreographed by a European.

Sitting around the stage are 150 shirtless and saronged men that are arranged in four concentric circles around the stage. Acting on cues from the actors like a Greek chorus the men chant "chaka chaka chaka,” wave their arms and rotate their bodies in unison while elaborately costumed solists act out episodes from the “Ramayana”. There are a lot of arguments about where "the wave" performed at stadium events began. Balinese have been doing it as part of the monkey dance for at least a 100 years.

Kecak is performed by a group of male dancers and usually performed in the evening. Kecak dancers sit on the ground surrounding a big torch while singing. They sing as though Balinese instrument sounds and are not accompanied by any music instruments whatsoever. The movements only use the hands and head. Sitting, singing, and dancing with their hands and upper torso, the chorus becomes, among others, the Ramayana’s army of monkeys. In the climax, the chorus, with a heightened feverish pitch, rises as it takes part in the events of the drama.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BALINESE DANCE: HISTORY, TYPES, STORIES. CHARACTERS factsanddetails.com

BALINESE MUSIC factsanddetails.com

BALINESE THEATER AND SHADOW PUPPETS factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CULTURE AND ARTS factsanddetails.com

ART AND CRAFTS IN BALI factsanddetails.com

BALINESE ARCHITECTURE: TEMPLES, TRADITIONAL BUILDINGS, COSMOLOGY factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF BALI: ORIGIN, KINGDOMS, MASS ROYAL SUICIDES factsanddetails.com

BALINESE: LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS, BEHAVIOUR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE SOCIETY: GROUPS, CASTE, THE SUBAK SYSTEM factsanddetails.com

LIFE IN BALI: VILLAGES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK, AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com

BALINESE RELIGION: HINDUISM, SPIRITS, TEMPLE LIFE, PRIESTS factsanddetails.com

History of the Monkey Dance

Kecak was performed for the first time in 1930 as an entertaining pastime dance among Balinese males. At that time, Kecak were only played in small celebrations such as during the harvest month or village anniversary. The development of drama in Bali, especially Sendratari, brought a changed to this dance. Kecak and Janger dances started to enter Sendratari’s scene which mostly performs classical stories such as Ramayana and Mahabratha. It is now usually performed regularly at Tanah Lot (in the Tabanan district) and Batubulan (Gianyar district). Kecak dance is also performed in many national and international events held in Bali.

The Kecak dance is based on an ancient choral dance tradition. At night, men sit in circles around a large oil lamp and chant the syllables "cak-kecak-cak" with immense strength and astounding rhythmic precision. The fast abdominal breathing and bursting vocals of this gamelan svara, or "voice orchestra," easily lead to hyperventilation and trance. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki]

It is believed that Walter Spies combined this archaic ritual tradition with a scene from the Ramayana in which Rama, Sita, and Ravana appear amidst the suggestive chorus to reenact Sita's abduction. Currently, Kecak is frequently performed in many villages, but the shows are mostly intended for tourists. Since the 1970s, several new versions of the dance have emerged. One of these is the all-female Kecak, which premiered at the Bali Arts Festival in 2004.

Describing the kepak, Jenny Heaton wrote in the Rough Guide to World Music, "Suddenly, with several short cries the men rise up, then sink down again, making a hissing sound. A single short shout follows and the men break into rhythmic chant...swaying from side to side, hands waving in the air. A solitary voice rises above the rhythmic chattering of the chorus, singing a quivering, wailing melody. Another short cry and the men sink down again." Wayan Limbak, a Balinese dancer who helped create the monkey dance, died in Gianyar, Bali, in 2003 at the age of 106.

Baris, the Balinese Warrior Dance

The term Baris derives from the Balinese word bebaris, meaning a line or group of soldiers. The dance portrays warriors preparing for or entering battle, with dancers carrying weapons such as tumbak (spears), keris (daggers), bows, shields, or even ceremonial firearms. Baris is typically performed by groups of 8 to 40 male dancers, whose costumes, weapons, and accessories distinguish the many variations of the form, including Baris Tumbak, Baris Panah, Baris Tamiyang, Baris Bedil, and Baris Jangkang. While many Baris variants appear at social events and festivals, Baris Gede is reserved for temple ceremonies. This sacred version is traditionally performed by boys before puberty and, like Rejang, functions as a ritual offering rather than entertainment. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki; Bali Tourism Board]

According to Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theatre Academy Helsinki, Baris Gede belongs to the most important group of wali (sacred) dances. It is an ancient ceremonial war dance performed by men arranged in disciplined formations, often numbering from six to sixty dancers. The choreography emphasizes synchronized group movement rather than individual virtuosity, creating the impression of a stylized battlefield through simple steps and leg movements. Historical sources indicate that Baris dances were already performed in the sixteenth century.

In ritual contexts, the dancers are regarded as the bodyguards of visiting deities. They wear tall, pyramid-shaped headdresses decorated with mother-of-pearl and carry sacred weapons that are often revered as temple heirlooms. Baris forms are classified according to the weapons used. Alongside these sacred versions, a modern secular Baris has also developed. This solo dance focuses on the emotional world of a warrior about to depart for battle, expressing courage, doubt, fear, and determination through sharp, angular movements, tense arm positions, and dramatic eye expressions. This secular Baris is frequently performed for tourist audiences.

Sanghyang: Balinese Trance Dances

Bali is renowned for its rich traditions of trance rituals, in which one or more participants enter altered states of consciousness through incense, chanting, music, prayer, and occasionally intoxicating substances. Trance rituals are widespread throughout Asia, but Bali is exceptional in the sheer number and variety of such practices found on a relatively small island. During these rituals, dancers—and sometimes members of the audience—may become possessed by gods, ancestral spirits, animal spirits, or other supernatural forces. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki; Bali Tourism Board]

Sanghyang (from sang, “lord,” and hyang, “god”) refers to a group of trance dances most commonly performed in rural villages, though abbreviated versions are sometimes presented for visitors. Numerous local variants exist. In many Sanghyang dances, male performers are possessed by animal spirits: in Sanghyang Jaran they become horses, in Sanghyang Lelipi snakes, and in Sanghyang Celeng pigs. These rituals serve a purificatory function; for example, dancers in pig trance symbolically consume dirt to cleanse the community of spiritual pollution. Because trance behavior can be unpredictable, priests and attendants closely supervise the performance to prevent injury. At the conclusion, holy water is sprinkled on the dancers to restore normal consciousness.

Sanghyang is believed to predate Hindu influence in Bali and remains one of the island’s most ancient ritual forms. It is thought to possess healing powers and to enable communication with natural and divine forces. Both men and women may participate, and the dance is accompanied by sacred chants known as Gending Sanghyang, sometimes reinforced with traditional instruments. The ritual follows three stages: Nusdus, the purification of the dancer through holy smoke; Masolah, when the spirit enters and the dancer moves freely in trance; and Ngelinggihang, when the spirit departs and the dancer is ritually restored. Known forms include Sanghyang Dedari, Deling, Bojog, Sampat, Celeng, and Jaran.

Other Balinese trance rituals have merged with dramatic forms, most notably the self-stabbing keris trance associated with Barong and Rangda performances. Some trance dances have also evolved into secular or commercial spectacles.

Sanghyang Dedari, the Trance Dance of the Maidens

The most celebrated Sanghyang form is Sanghyang Dedari, traditionally performed by prepubescent girls believed to be especially receptive to divine possession. In its most authentic form, only young girls—often around eight years old—are permitted to dance, and they receive no formal training. Instead, their movements are believed to be guided entirely by spirits, identified as celestial nymphs or “star maidens.” [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki; Bali Tourism Board]

In a typical performance, two or more girls dance in perfect unison with their eyes closed, having been induced into trance by chanting priests. Hypnotic rituals may include the use of small puppets, incense, and repetitive chants. As the music intensifies, the girls glide and spin with fans and sticks, later dancing atop the shoulders of men from the audience without physical support. At the climax, they may dance barefoot across glowing embers without injury. A sudden ritual sound marks the end of the trance, and the priest restores the dancers to consciousness.

Dr. Miettinen describes Sanghyang Dedari as the most beautiful of the trance dances. Its highly expressive, almost feverish movement vocabulary—partly inspired by ancient animal motifs—has strongly influenced later classical forms, particularly Legong.

Legong, the Dance of the Maidens

Legong is one of Bali’s most refined classical dances, traditionally performed by two young girls accompanied by an attendant. It is often linked to Sanghyang Dedari and is believed to have evolved from trance-based rituals. Legong dancers wear richly ornamented silk and gold costumes, tightly wrapped around the waist, with elaborate headdresses adorned with flowers. Facial makeup is precise, emphasizing expressive eye movements. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki; Bali Tourism Board]

The most famous version, Legong Keraton, recounts an episode from the Panji cycle in which the King of Lasem abducts Princess Rangkesari. When she refuses his advances, the king goes to war to defend his claim, ignoring ominous signs that foretell his defeat. The story is conveyed through highly stylized movement rather than explicit narrative.

Legong means “beautiful movement” (leg) and “gong,” referring to its close relationship with gamelan music. It is one of the most technically demanding Balinese dances, requiring exceptional sensitivity to musical cues. The dance is accompanied by Gamelan Semar Pagulingan, a small, refined ensemble with a delicate sound. Over time, regional variants developed, but Legong Keraton remains the most widely performed and is often presented to welcome distinguished guests.

Legong represents the classical standard of Balinese female dance. Created around the turn of the eighteenth century, it combines elements of gambuh court drama and Sanghyang trance dances. Originally performed by young boys, it was later rechoreographed for girls by royal decree. Although modern performances often feature adult dancers, traditional training begins in early childhood, with movements taught through rigorous physical guidance until the dance becomes instinctive.

Female Group Dances

Pendet originated as a sacred temple dance performed by four or five prepubescent girls who carry flower-filled bowls and scatter petals as offerings to welcome the gods. Its movements are simple and form the foundation of Balinese dance technique. Over time, Pendet developed into a secular welcoming dance widely performed at ceremonies and public events. Belibis, inspired by the graceful movements of swans, is another welcoming dance performed by groups of girls. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki; Bali Tourism Board]

Rejang is a strictly sacred wali dance performed exclusively by women during temple rituals. Larger in scale than Pendet, Rejang may involve ten or more dancers moving slowly in long, circling lines around the temple courtyard. The leader carries holy water to purify the space. Variants such as Rejang Dewa, Rejang Galuh, and Rejang Oyopadi are distinguished by costume and ritual context.

Dr. Miettinen notes that Rejang’s simple choreography and dignified pace evoke a profound sense of beauty. Related dances such as Gabor function as offering rituals and have also developed secular forms used to welcome guests at public performances.

Barong and Rangda

The figures of Barong and Rangda embody the eternal struggle between positive and negative forces. Barong, the benevolent protector, appears as a composite animal—often lion-like—animated by one or two dancers within a large costume. Rangda, his terrifying counterpart, is a witch with bulging eyes, tusks, and wild hair, associated with destruction and black magic. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki; Bali Tourism Board]

Their confrontation is most famously enacted in the Calonarang dance-drama, performed to gamelan accompaniment. Barong’s followers attack Rangda with magical keris daggers, only to be thrown into trance by her powers. While some performances end in a stalemate, Rangda typically retreats, restoring cosmic balance.

Dr. Miettinen emphasizes that Barong and Rangda are not merely theatrical characters but sacred beings whose consecrated masks are kept in village temples as powerful protectors. Barong figures, believed to have roots in ancient Chinese lion dances, have evolved into uniquely Balinese forms such as Barong Ket (lion), Barong Macan (tiger), and Barong Bangkung (boar). Revered as guardians of the community, Barong figures are paraded through villages during festivals, reinforcing social bonds and spiritual protection.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Indonesia Tourism website

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026