CHINESE PAINTING

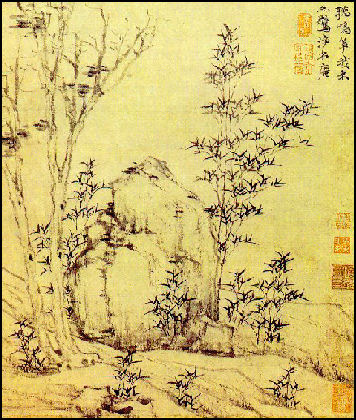

Autumn Wind by Ni Zan When people think of Chinese painting they think of graceful, harmonious, images of flowers, birds, water, mountains, trees and other natural objects. "There is no art in the world more passionate than Chinese painting," wrote New York Times art critic Holland Carter. "Beneath its fine-boned brush strokes, ethereal ink washes and subtle mineral tints flow feeling and ideas as turbulent as those in any Courbet nude or Baroque Crucifixion."

There are two major traditions of classical painting in China: 1) the court tradition, depicting urban and rural scenes often in great detail; and 2) the literary tradition, with evocative landscapes and still lives. Many Chinese paintings are covered with stamps. These are from artists and scholars who liked what they saw and left their seals as testimony of their approval. They are kind of like artistic applause. [Source: Stevan Harrell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia - Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Chinese painting can be divided into two major modes; a meticulous and detailed one (kung-pi) and a free, expressionistic one called "sketching ideas (hsieh-i)." A middle path, however, is often adopted to avoid extremes and capture accurately the outer form as well as the inner spirit. The traditional artist may paint with great detail, but would not just copy exterior forms; or, the artist may paint with abandon and set aside the rules of representation, but not go so far as to create abstract art. Whether a vast overview or an intimate scene, the goal of the artist is to lead viewers into a painting and create a realm unto itself. Furthermore, the Chinese (writing with the brush) naturally transfer the techniques of calligraphy to painting. As sister arts, they often appear together. When combined with poetry and the seal, the work is complete in form and spirit to create one of the enduring features of Chinese painting. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Many of the best-known Chinese paintings are depictions of nature. According to Eleanor Stanford: “Landscapes strive to achieve a balance between yin, the passive female force, represented by water, and yang, the male element, represented by rocks and mountains.” Chinese paintings often have seal marks or writing on them, sometimes by the artist and sometimes by a scholar from a later era. The writing can be a poem, a dedication, or a commentary on the work. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

See Separate Articles: CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; ART FROM CHINA'S GREAT DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTING FORMATS AND MATERIALS: INK, SEALS, HANDSCROLLS, ALBUM LEAVES AND FANS factsanddetails.com ; GREAT AND FAMOUS CHINESE PAINTINGS factsanddetails.com ; SUBJECTS OF CHINESE PAINTING: INSECTS, FISH, MOUNTAINS AND WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTINGS OF GHOSTS AND GODS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TAOIST ART: PAINTINGS OF GODS, IMMORTALS AND IMMORTALITY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTERS factsanddetails.com ; PAINTING FROM THE TANG, SONG, YUAN, MING AND QING DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; TANG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ANIMAL, RELIGIOUS AND FIGURE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; YUAN ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; MING DYNASTY PAINTING AND ITS FOUR GREAT MASTERS factsanddetails.com ; QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Painting” by James Cahill (Rizzoli 1985) Amazon.com; “Chinese Painting Style: Media, Methods, and Principles of Form” by Jerome Silbergeld Amazon.com; “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” by Richard M. Barnhart, et al. (Yale University Press, 1997); Amazon.com; “How to Read Chinese Paintings” by Maxwell K. Hearn (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008) Amazon.com; “Brushstrokes: Styles and Techniques of Chinese Painting” by So Kam Ng Lee and So Kam Ng Amazon.com ; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Early Chinese Paintings and What They Express

Painting of a painter The oldest paint brush found in China — made with animal hair glued on a piece of bamboo — was dated to 400 B.C. Silk was used as a painting surface as early as the 3rd century B.C. Paper was used after it was invented I the A.D. 1st century. The oldest existing Chinese paintings are Buddhist works painted in caves and temples.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““As early as the Neolithic age in the history of Chinese painting, prehistoric inhabitants began to paint on the ceramic vessels they made. During the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties (20th to 3rd centuries B.C.), artisans revealed considerable skill in producing an amazing variety of designs and images on bronzes, jades, ceramics, and textiles. During the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-AD 220), pictorial art was also rendered on stone, walls, and silk. Bold representations of figures, birds, and animals were the main subjects, and the solemn style then was suited to the notion of art as a medium to "instruct and moralize." From the 3rd to 6th century, the concept of "art for art's sake" gradually arose. Figure painting was imbued with an air of refined beauty that was sometimes unchecked by convention. As Buddhism took hold in China, temples increasingly dotted the landscape. Combined with the Taoist affinity for Nature and the Confucian ideal of reclusion, artists increasingly turned their attention to the land for spiritual freedom. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “We know from textual and archaeological sources that painting was practiced in China from very early times and in a variety of media. Wall paintings were produced in great numbers in the early period of China's history, but because so little early architecture in China remained intact over the centuries, few of these large-scale paintings have survived. Paintings were also often done on screens, which served in a sense as portable walls, but these too have not survived. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

From the Song dynasty onwards, paintings in a variety of other more portable formats, such as the hanging scroll and the handscroll, were collected and passed on to later generations in significant quantities. In their details of everyday life and social customs, these paintings often provide information unavailable from written texts. Many paintings are especially interesting to historians because they can help us imagine what life looked like in earlier periods. Furthermore, because paintings of this period have come to be viewed as one of the highest cultural achievements in China's history, they provide valuable insight into aesthetic values and tastes that would have lasting impact on later artists and connoisseurs.

Because many painters created highly detailed scenes of daily life, we can look at paintings for the information they provide about social life during this period. Painting as an art form also reached a very high standard of quality during the Song, which is considered by many to be a high point in the development of the fine arts in China. Landscape themes began to dominate painting during this period, and would continue to be a favorite subject of artists up into the modern period.

History of Chinese Painting

According to the Shanghai Museum: Chinese painting is an art, which has a deep-rooted tradition and a unique style, employing a ‘dots and lines’ structure and the writing brush, ink stick, silk and Xuan paper as the main tools. Chinese painting developed from the Warring States period (475-221 B.C.) to the Qin and Han dynasties (221 B.C.-A.D.220). Paintings depicting the human figure emerged as early as the Warring States period and attained maturity during the Wei, Jin, the Northern and Southern Dynasties period. (A.D. 220-589) [Source: Shanghai Museum ^^]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““The repertoire in painting expanded in the Tang dynasty (618-907) as figure painting flourished and reached a high point. Landscape as a genre matured, and forms were carefully drawn with rich colors. The technique of applying washes of monochrome ink also developed in which images were captured with abbreviated, suggestive forms. During the late Tang and Five Dynasties period (907-960), great advances were made in bird-and-flower and animal painting. Two major schools formed in bird-and-flower painting; an opulent style versus a free mode of natural expression. Song (960-1279) artists continued to pursue the beauty of the land. Whether it be the rugged peaks of northern China or the misty rolling hills of the south, painters created scenes in which viewers could travel, gaze, wander, and dwell. In bird-and-flower, animal, and figure painting, artists not only accurately rendered the appearance of forms but also captured the essence of the spirit. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw =]

The Tang and Song dynasties (A.D. 618-1279) saw the zenith of paintings of portraits, landscapes, flowers and birds. The artists of this period used realistic representative styles and techniques, including a meticulous manner with heavy colors, monochrome ink-wash painting, splash-ink technique and the ‘boneless’ painting method. Literati painting rose to prominence in the Song dynasty (A.D. 960-1279). In the Yuan dynasty (A.D. 1279-1368), it became the mainstream of Chinese painting. Literati painting stresses a subjective approach to nature through the use of brush strokes and poetic mood. Xuan paper became widely used at this time and became the favorite medium to express the beauty of brush and ink drawings. Literati painting developed the former realistic style into a new expressionist ‘Xieyi’ style, pursuing the aesthetic appeal of brushwork. ^^

“In the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), painters turned even further to ideas in art. Scholar-artists led the way with their expressive brushwork, and they were well suited to transmitting feelings with their calligraphic style often characterized by simplicity, understatement, and transcendent elegance. After the founding of the Ming (1368-1644), the Yuan scholar style continued, but the ink-wash painting of the Song court became popular. By the middle of the Ming, however, the elegance of Yuan scholar painting was again admired. =

In the Ming and Qing dynasties (A.D. 1368-1911), two prevailing trends emerged: imitation of the past and creative innovation. The painters developed a new style by emphasizing artistic, abstract expression in combination with poetry, calligraphy and painting. This period was marked by the kaleidoscopic richness of regional schools and personal styles. In the late Ming and early Qing (1644-1911), scholar painting flourished even more as two approaches arose. One involved artists learning to paint through careful copying of ancient models, while the other involved abandoning models in favor of individual creativity. By the middle Qing, the latter gained popularity. In the late Qing, research on ancient inscriptions in stone and bronze influenced painting, further instilling it with renewed vigor. = ^^

Chinese Approaches to Works of Art

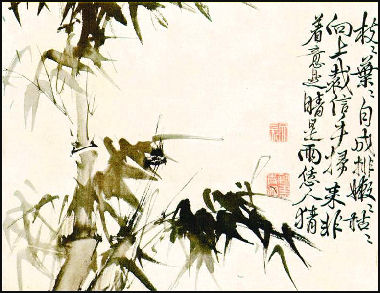

Bamboo by Zhu Wei

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Personal Expression Valued Over "Realism": Although "realistic" painting in the European style was very much in vogue at the Qing court, where it was appreciated for its documentary value in commemorating the Qianlong Emperor's exploits, it was not regarded as "high art." The Chinese and their Manchu rulers held to the belief that the highest form of pictorial expression was traditional Chinese painting, which privileged the personal expression of the individual artist over the representation of external appearances. Since the 14th century what mattered most in Chinese painting was the artist's ability to express his personal feelings — to create an image of his interior world — rather than to describe the external appearances of things. As a result, most Chinese painting connoisseurs regarded the European style as little more than a gimmick. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant, learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu]

“The Importance of Poetry for Artists and Connoisseurs: Chinese literati artists often wrote poems directly on their paintings. This practice emphasized the importance of both poetry and calligraphy to the art of painting and also highlighted the notion that a painting should not try to represent or imitate the external world, but rather to express or reflect the inner state of the artist. The artist's practice of writing poetry directly on the painting also led to the custom of later appreciators of the work — perhaps the initial recipient of the painting or a later owner — adding their own reactions to the work, often also in the form of poetry. These inscriptions could be added either directly on the surface of the painting, or sometimes on a sheet of paper mounted adjacent to the painting. In this way some handscrolls accommodated numerous colophons by later owners and admirers. Thus in Chinese art the act of ownership entailed the responsibility of not only caring for the work properly, but to a certain extent also recording one's response to it.

“The Qianlong Emperor (ruled 1735-1796.) was an avid collector and connoisseur of Chinese art, and the number of paintings and artifacts collected during his reign was unprecedented. Many palace halls were used specifically for the Emperor to admire and study works of art. The Qianlong Emperor had a tendency to admire the works he collected and commissioned by adding a great number of seals and inscriptions — usually in the form of poems — to the works. In so doing, the emperor not only endowed these works of art with the imperial imprimatur but also, by leaving his mark on some of the most important works of Chinese art, asserted his control over Chinese culture and his legitimacy as the ultimate connoisseur of Chinese art. Often he must have had ghost writers helping him inscribe these poems, but he did write many of them himself. In fact, the Qianlong Emperor is said to have composed some 40,000 poems, and many of them are inscribed on the enormous collection of paintings amassed during his reign. As a result, the Qianlong Emperor's inscriptions and seals appear on hundreds of the most important Chinese paintings that exist today.

“The Work of Art as a Dialogue with the Past: The Role of Owners and Connoisseurs, One of the most extraordinary characteristics of Chinese painting is that, in a way, a painting is never quite finished. What does this mean? Just as the artists themselves used poetry as a medium of expression in painting, later appreciators of a painting felt free to add to it by writing a poem in response to the work, or sometimes just adding a personal seal, directly on the surface of the painting or to the silk mounting bordering the painting. In this way a painting remains "open-ended," and viewing a painting is like engaging in an ongoing conversation, not only with the artist, but with all the people who have in the past owned the work and have recorded their response to it. And through this visual record, a painting's provenance can be traced, so that literally written on the surface of the painting is the very history of who owned it, how people over time have appreciated it, and how different eras saw its merits in a different light. When a connoisseur looks at a painting today, he or she not only examines the work, but takes great delight in seeing which other collectors owned it, and what some of these owners and other commentators have had to say about it.”

Literati Versus Academic Chinese Painting

According to the literati ideal in imperial and traditional China an educated gentlemen aspiring to government service should also be an accomplished poet and painter. Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “ By looking at the way that the members of the governing elite approached the art of painting, we can gain some further insight into the way in which they conceived and tried to live up to the literati ideal. The key division that we will emphasize here is one between men who were called "academic" painters, and those who were seen as painters in the literati tradition. What's the difference? [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University]

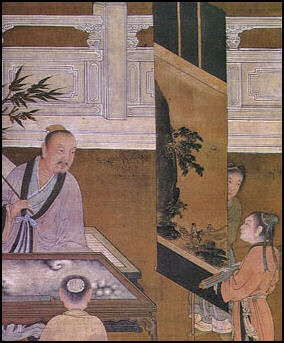

"Academic painters" were highly skilled craftsmen, who aimed to achieved marvelous effects through their use of colors, realistic or highly conventional representations of people or things, spectacular detail, applications of shiny gold leaf, and so forth. The Imperial court employed many such men, and others made their way in the world by selling their paintings to wealthy patrons and customers. Academic painters were professionals, both in their virtuoso skills, and in the fact that they depended on permanent employment as painters, or on selling their paintings to live. While many of these men were educated to some degree, few possessed the literary background of a literatus, and none made their way in life fulfilling the Confucian ideal of governmental service. "Literati painters," on the other hand, were amateurs — they painted as a means of self-expression, much the same way they wrote poetry; both forms were inheritances from the Neo-Daoist era of the Six Dynasties. While many fewer literati were accomplished painters than were poets (and painting was never an aspect of the exams), in every major place in China there were always many literati who either painted on the side, while playing the role of scholar-officials, or who, through wealth, could afford to devote themselves fully to the art of painting.

“Literati painting was conceived as mode through which the Confucian junzi (noble person) expressed his ethical personality. It was much less concerned with technical showiness. Literati painters specialized in plain ink paintings, sometimes with minimal color. They lay great emphasis on the idea that the style with which a painter controlled his brush conveyed the inner style of his character — brushstrokes were seen as expressions of the spirit more than were matters of composition or skill in realistic depiction. /+/ While literati poetry developed fully during the Tang Dynasty on the basis of long Six Dynasties preparation, painting did not become central to literati until later. Although we hear of famous poet-painters of the Tang, because their works have not survived it is difficult to know to what degree their art differed from academic painting. During the late Song, however — that is, after about 1200 — literati and academic painting become two distinct streams. Interestingly, although academic paintings were often far more skilled in technique, many felt — and still feel — that the "amateur" ink paintings of the literati are the highest form of art in China. The most important of the painters we will look at is a man named Shen Zhou (1427-1509), who lived during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).” His approach to his art illustrates many key facets of the Confucian-Daoist literati ideal, translated into an approach to painting.

Literati Painting

Zhang Zhen, an expert in ancient Chinese painting and calligraphy with the Palace Museum in Beijing told the China Daily that while the origin of literati painting can be traced to an earlier time, it was only during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), a pinnacle in Chinese art and literature, that more literary-minded people with an artistic bent began to experiment in broadening painting's languages and meanings. "As the name suggests, literati paintings were done by people who were reared on the country's literary tradition," says Zhang Zhen, an expert in ancient Chinese painting and calligraphy with the Palace Museum in Beijing. "And since they belonged to the sophisticated social elite and were presumably well-off, they didn't have to sell their works to live. They painted not for a clientele, but for themselves, and for them painting was more a form of entertainment and introspection than a means of living." [Source: Zhao Xu And Su Qiang, China Daily, December 19, 2015]

Zhao Xu And Su Qiang wrote in the China Daily: “For these artists, painting was, in a word, cathartic. The still waters under their brushes served up reflections of themselves as cultured, sensitive men. (And yes, they were, to a man, men). Some saw their professional counterparts, who were often born into poor families and received little education apart from how to paint, as worth less than themselves.

And this movement, for want of a better word, found a forceful advocate in Zhaoji, or Emperor Huizong (1082-1135), the eighth ruler of the Song Dynasty, whose artistic achievements tower over some of the best-known artists in Chinese history. Huizong perfectly fits the bill that Yang Danxia, Zhang's colleague at the Palace Museum, offers for a literati painter. "A literati painter must be one who had a fairly good mastery of Chinese literature and calligraphy. Consequently, his works exude feelings befitting an enlightened, sensitive mind. Painting with a literary subtext - that's what they were aiming for."

“These criteria changed what was depicted on paint scrolls, especially later on. Colors were giving way to black ink and a detail-obsessed style to a freer, less arduous one. However, this did not entail less thought, but the opposite. Natural scenery was often preferred, partly because it required less training to paint mountains and rivers than it does for other genres, portraiture for example. The painting would often depict a world with an otherworldly beauty and serenity, distant, even desolate. Theories concerning the application of ink and brush developed based on calligraphic principles. "To write or to paint, people in ancient China used the same brush," Tian says. "And they eventually sought to judge paintings against criteria similar to those used in judging works of calligraphy, looking for the strength and smoothness of brushstrokes."

Chinese Painting and Calligraphy

In imperial times, painting and calligraphy were the most highly appreciated arts in court circles and were produced almost exclusively by amateurs — aristocrats and scholar-officials — who alone had the leisure to perfect the technique and sensibility necessary for great brushwork. Calligraphy was thought to be the highest and purest form of painting. The implements were the brush pen, made of animal hair, and black inks made from pine soot and animal glue. In ancient times, writing, as well as painting, was done on silk. But after the invention of paper in the first century A.D., silk was gradually replaced by the new and cheaper material. Original writings by famous calligraphers have been greatly valued throughout China's history and are mounted on scrolls and hung on walls in the same way that paintings are. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Painting in the traditional style involves essentially the same techniques as calligraphy and is done with a brush dipped in black or colored ink; oils are not used. As with calligraphy, the most popular materials on which paintings are made are paper and silk. The finished work is then mounted on scrolls, which can be hung or rolled up. Traditional painting also is done in albums and on walls, lacquerwork, and other media. *

Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The discipline” of painting this kind of mastery requires derives from the practice of calligraphy. Traditionally, every literate person in China learned as a child to write by copying the standard forms of Chinese ideographs. The student was gradually exposed to different stylistic interpretations of these characters. He copied the great calligraphers' manuscripts, which were often preserved on carved stones so that rubbings could be made. He was also exposed to the way in which the forms of the ideographs had evolved. Over time, the practitioner evolved his own personal style, one that was a distillation and reinterpretation of earlier models. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art ]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: ““The "calligraphic" use of the brush became in China a separate art form, and one that exerted great influence on literati painting. Beginning in the period of the Six Dynasties (220-589), mastery of self-expression through well and distinctively written (actually, "brushed") characters was an important part of being a well bred member of the elite. The earliest exemplars of calligraphic mastery were members of the refugee elite families of Southern China, who were apparently influenced by a tradition of inspired "automatic writing" associated with traditions of Daoist religious practice. Foremost among these was Wang Xizhi (303-361), whose calligraphy has remained one exemplar for the art of writing in China ever since, and whose brush style contributed to the common standard "font" for writing Chinese characters throughout the traditional period. (The example below, from his most famous work and bearing the seals of a Qing Dynasty emperor, is likely a copy rather than an original, as is probably true of all existing remnants of his style.) [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University]

History of Chinese Painting and Calligraphy

Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: Chinese ideographs evolved from “their earliest appearance on bronzes, stones, and bones about 1300 B.C. (known today as "seal" script, after its use on the red seals of ownership); their gradual regularization, culminating with the bureaucratic proliferation of documents by government clerks during the second century A.D. ("clerical" script); their artful simplification into abbreviated forms ("running" and "cursive" scripts); and the fusion of these form-types into "standard" script, in which the individually articulated brushstrokes that make up each character are integrated into a dynamically balanced whole...The practice of calligraphy became high art with the innovations of Wang Xizhi in the fourth century. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

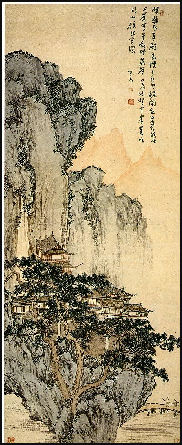

Beginning in the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907), the primary subject matter of painting was the landscape, known as shanshui (mountain-water) painting. In these landscapes, usually monochromatic and sparse, the purpose was not to reproduce exactly the appearance of nature but rather to grasp an emotion or atmosphere so as to catch the "rhythm" of nature. In Song dynasty (960-1279) times, landscapes of more subtle expression appeared; immeasurable distances were conveyed through the use of blurred outlines, mountain contours disappearing into the mist, and impressionistic treatment of natural phenomena. Emphasis was placed on the spiritual qualities of the painting and on the ability of the artist to reveal the inner harmony of man and nature, as perceived according to Taoist and Buddhist concepts. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Beginning in the thirteenth century, there developed a tradition of painting simple subjects — a branch with fruit, a few flowers, or one or two horses. Narrative painting, with a wider color range and a much busier composition than the Song painting, was immensely popular at the time of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). *

During the Ming period, the first books illustrated with colored woodcuts appeared. As the techniques of color printing were perfected, illustrated manuals on the art of painting began to be published. Jieziyuan Huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden), a five-volume work first published in 1679, has been in use as a technical textbook for artists and students ever since. *

Chinese Painting, Calligraphy and Poetry

Poetry is much more fully integrated into painting and calligraphy in Chinese art than it is into painting and writing in Western art. There are two words used to describe what a painter does: “Hua hua” means "to paint a picture" and “xie hua” means "to write a picture." Many artists prefer the latter.

Poetry is much more fully integrated into painting and calligraphy in Chinese art than it is into painting and writing in Western art. There are two words used to describe what a painter does: “Hua hua” means "to paint a picture" and “xie hua” means "to write a picture." Many artists prefer the latter.

Poetry, painting and calligraphy were known as the "Three Perfections." Poems are often the subjects of painting. Painters were often inspired by poetry and tried to create works with a poetic, lyrical quality. Recalling a series of twelve poems by Su Shih (1036-1101) that inspired him, the great master painter Shih T'ao (1641-1717) wrote: "This album had been on my desk for a year and never once did I touch it. One day, when a snow storm was blowing outside, I thought of Tung-p'o's poems describing twelve scenes and became so inspired that I took up my brush and started painting each of the scenes in the poems. At the top of each picture I copied the original poem. When I chant them the spirit that gave them life emerges spontaneously from paintings." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

When a painting did not fully convey the artist feelings, the artist sometimes turned to calligraphy to convey his feelings more deeply. Describing the link between writing and painting, the artist-poet Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) wrote:

“Do the rocks in flying-white, the trees in ancient seal script

And render bamboo as if writing in clerical characters:

Only if one is truly able to comprehend this, will he realize

That calligraphy and painting are essentially the same.”

Other times the message of the calligraphy was more mundane. An inscription on the side of “Sheep and Goat” by Zhao Mengfu read: "I have painted horses before, but have never painted sheep, so when Zhongxin requested a painting, I playfully drew these for him from life. Though I can not get close to the ancient masters, I have managed somewhat to capture their essential spirit”.

Difference Between Chinese and Western Painting

Art in the East developed very differently from art in the West. In China, calligraphy (the art of making letters) and painting evolved together and thus painting, the graphic arts, poetry and literature became linked together in way they never did in Europe. The expressive and philosophic aspirations of Chinese painters were much higher than their counterparts in the West. Historian Daniel Boorstin wrote in “The Creators”, "their works were less varied in subject matter, color and materials. Their hopes and their triumphs offered nothing like the Western temptations to novelty, and their legacy is not easy for Western minds to understand." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Linear perspective was introduced by Europeans. The Italian Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci criticized Chinese art in the 16th century for its lack of perspective and shading, saying it looked "dead" and didn't have "no life at all." The Chinese for their part criticized oil painting brought by the Jesuits as being too lifelike and lacking expression.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In the West, in Greco-Roman times and again in the Renaissance, artists created the illusion of spatial depth on a flat surface through the use of linear perspective, which meant that implied parallel lines were drawn to intersect at an imaginary point on the horizon called the "vanishing point," and all forms were rendered in scale and positioned to correspond to these guiding lines. As a result, there is a kind of geometric logic to the composition in Western painting, and the viewing frame (which can be seen all at once, unlike in a Chinese handscroll painting) was experienced as a kind of "window" onto another world. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant]

“Pictorial space in Chinese painting is defined somewhat differently from the foreground, middle ground, and background typically found in traditional Western painting. In Scroll Three of the Kangxi Inspection Tour series, three distinct classifications of pictorial space, as defined by the 11th-century artist Guo Xi, can be seen in the artist's treatment of the mountains: "From the bottom of the mountain looking up toward the top, this is called 'high distance' (gaoyuan). From the front of the mountain peering into the back of the mountain, this is called 'deep distance' (shenyuan). From a nearby mountain looking past distant mountains, this is called 'level distance' (pingyuan).", — From Guo Xi and Guo Si, Lin quan gao zhi (Lofty Ambitions in Forests and Streams), in Yu Jianhua, ed., Zhongguo hualun leibian (Compendium of essays on Chinese paintings).

Chinese Way of Representing Space and the External World

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “By the 13th century, Chinese artists had mastered the illusion of recession in space. But after this time, the representation of space and the description of the external world gradually ceased to be the principal objective of artists. Working on a flat surface — such as a canvas or a scroll — an artist faces the challenge of creating the illusion of three-dimensional forms on a two-dimensional surface. This is a problem for which artists both in the East and the West found solutions, but their solutions were very different. European painting after the 15th century tended to treat a painting as though the canvas were a window through which an illusionistic three-dimensional scene could be viewed; Chinese painting created the experience of space by means of a moving perspective that allowed the viewer's eye to explore the pictorial space from a shifting vantage point, so that, in the case of a long handscroll such as those chronicling an emperor's journey, space is experienced through the continuous unrolling of the work. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant]

Chinese artists' approach to the problem of representing spatial depth on a flat surface is quite different from that of their Western counterparts. In fact, the very formats that are used in Chinese painting — particularly the long handscroll — have an impact on how pictorial space itself is conceptualized in the Chinese painting tradition. Imagine unrolling a scroll painting, for instance, from right to left as one would in viewing a Chinese painting. The scroll may be as long 60, 70, or even 80 feet, so it is impossible to see much more than a small section of the entire painting at once. And in fact, the work was not meant to be seen all at once.

Unlike a traditional Western painting, which is contained within a distinct frame, a painting on a long scroll that has to be unrolled section by section would not make sense visually if it were composed with a technique such as linear perspective, which depends on the use of a single, fixed vanishing point. In a long scroll, the viewer controls the boundaries of the viewing frame at any single moment, and the pictorial space unfolds as the viewer unrolls the scroll. In this way, the handscroll format requires that the pictorial space remain fluid. As in traditional Western compositions, there is a foreground, a middle ground, and a far distance, but the artist continuously shifts the focus of the composition so that the viewer's apparent vantage point is constantly changing, enabling him or her to easily navigate the pictorial space unhindered by the constraints of a fixed vanishing point.”

Chinese Painting Styles and Goals

By the Tang dynasty the criteria for good painting had been established. One of the main objectives was capturing the “qi”, or life force, of the subjects. In the Tang dynasty artists favor figures over landscapes. As time went by the reverse became true.

Chinese painting can be divided into three major stylistic forms: 1) the meticulous, detailed “kung-pi” style and 2) the free, expressive “hsieh-I” ("sketching ideas") style. 3) The middle path avoids both extremes and tries to capture the "inner spirit" of the subjects, which has always been more important than simply rendering the outward form.

One of the most important notions of classical Chinese painting was the "Concealment of Brilliance." Overt expressions of technical skill were considered vulgar. "Creativity and individuality were highly valued," but only in an understated way "within the framework of tradition."

Whether the subject of a work of art is a single dignified mountain or range with a thousands peaks and valleys, the goal of Chinese painting is to draw the viewer into the painting a create a "kind of reality like the palpable world." Artists who chose the liberated approach kept their energies focused and never followed their emotions and thoughts to the point they created abstract or representative art. Artists who painted extremely fine details did not copy their subjects.

Color, Shading and Perspective in Chinese Painting

Confined by the tools of the calligrapher, Chinese painters all but ignored color. Shading was regarded as a European technique, introduced second-hand by Buddhist missionaries in the A.D. 3rd century.

Classic Chinese artists never developed the idea of central perspective and the vanishing point which were essential to the development of Renaissance art in Europe. "Instead," Boorstin wrote, "the Chinese captured space in their painting, by an invisible linear perspective that diminished objects in the distance, and by aerial perspective that made distant objects increasingly indistinct.

The Chinese developed and classified three personal points of view, all related to ways of viewing a landscape: the "level distance" perspective, where the spectator looks down from a high vantage point; the "deep distance perspective," where the spectator's vision seems to penetrate into the landscape; and the "high distance" perspective, where the spectator look up. This helps explain why the Western observer feels strange when looking at a Chinese painting. And also why Chinese paintings seem to need no frame." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Copying, Forgeries and Fakes

New York Times art critic Holland Carter wrote, "Debates about authenticity have always been part of art in China, where 'originals' are often chimerical things, creative copies are revered as supreme masterpieces and distinctions between copying and forging are fuzzy." What is regarded as fake in the West is often treated with great reverence in China. Even great Chinese masters copied works of their predecessors right down to their signatures and seals. Chiang Dai-chein, regarded by many as China's greatest 20th century artist, was an expert forger who sold thousands of paintings attributed to classic painters. The wide availability of counterfeit goods and indifference to copyright laws today shows the notions of individualism and individual ownership remain weak in China.

"Zhao Xu And Su Qiang wrote in the China Daily:““The painter Qian Xuan (1239-1299) was a prodigious user of personal hallmarks. Qian, who lived in a time of dynastic change, admitted to having signed works with "a byname never used before", in order to "stop and shame my imitators". What makes this particularly remarkable is that Qian, also a much-celebrated poet and essayist, had long championed the view that true artists should not be influenced in their creative work intent to pander, and that their works certainly should not be traded for money. [Source: Zhao Xu And Su Qiang, China Daily, December 19, 2015]

"The inspiration of nature and past masters," wrote Boorstin, "gave a special kind and continuity, originality, and inwardness to painters. ...Forgery acquired a new ambiguity. The Chinese artists' proverbial talent for copying leads reputable art dealer nowadays to be wary of offering 'authentic' old Chinese paintings. Seeking constant touch with the past and the works of great masters by hanging pictures on the wall in rotation according to the seasons or festivals, the Chinese created a continuing demand that supported workshops for mass production by professional painters. These artists following the Tao showed remarkable skill in making both new originals and copies of copies.” [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Michele Cordardo, the director of the Central Conservation Institute in Rome, was invited to China to work in Xian. He told The New Yorker, "The Chinese have a different sense of the value of original and copy...The Chinese...have a tradition of conserving by copying and rebuilding...This system of considering by copying or rebuilding works well as long as you keep the artisan traditions intact. The problem is that those traditions have broken down in China...Once the continuity of Chinese imperial civilization came to an end knowledge of traditional pigments, resin, and textiles, and techniques of painting, wood carving or building quickly began to disappear."

FORGING AND COPYING CHINESE ART See Separate Article factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: 1, 14) Wikipedia; 2, 4, 8, 9, 10) University of Washington; 3) Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; 5, 6, 7 ) China Beautiful website; 9, 12) Palace Museum, Taipie; 11, 13) Metropolitan Museum of Art; 14) Shanghai Museum. Luo Ping ghost painting from the Met in New York, Nelson-Atking Museum, Ressel Fok collection, Shanghai Museum

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021