SUBJECTS OF CHINESE PAINTING

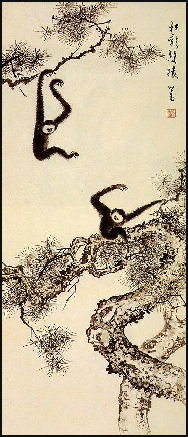

Gibbons

The three main subjects of Chinese painting have traditionally been landscapes, birds-and-flowers, and figures. Chinese artists, wrote Boorstin, painted a "limited number or appropriate subject matters and these could be depicted in a certain number of techniques...To the inexpert Western eye, the Chinese painter seems less an original creator than a performer — like an inspired Western musician playing the composition of great artists before seasoned listeners." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Even though painting techniques changed over time the subjects remained pretty constant, and included portraits, dragons and fishes, landscapes, animals, flowers and birds, vegetables and fruit, wild scenery and the hermit scholar. Things like pine trees, bamboo, rocks, mountains and running water were important symbols with easily recognizable meanings. Portraits were usually of emperors and noblemen.

"Ink bamboo," a subject that unified calligraphy and painting, was an especially popular subject. During the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) some painters painting nothing but bamboo their entire careers. Bamboo often symbolized the inner personality of the artist as the gentleman scholar. Bamboo stalks bend but don't break like a true scholar that adjusts with the times but stays true of his ethics. Bamboo was also a symbol of the ability to endure oppression.

"The composition, too," wrote Boorstin, "expressed the order of nature, with a tension between giving and taking, passive and aggressive, host and guest. In a group of trees, the “host” tree will be bent with spread branches, and the guest tree slim and straight. If a third tree is added, it must not be exactly parallel. Such a group of trees can itself be a host in relation to another “guest group” in another part of the painting...The host-guest principal of tree to tree can equally be applied to the relation of rock to rock, mountain to mountain, or man to man." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

See Separate Articles: CHINESE PAINTING: THEMES, STYLES, AIMS AND IDEAS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; ART FROM CHINA'S GREAT DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTING FORMATS AND MATERIALS: INK, SEALS, HANDSCROLLS, ALBUM LEAVES AND FANS factsanddetails.com ; GREAT AND FAMOUS CHINESE PAINTINGS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTINGS OF GHOSTS AND GODS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TAOIST ART: PAINTINGS OF GODS, IMMORTALS AND IMMORTALITY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTERS factsanddetails.com ; PAINTING FROM THE TANG, SONG, YUAN, MING AND QING DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; TANG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ANIMAL, RELIGIOUS AND FIGURE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; YUAN ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; MING DYNASTY PAINTING AND ITS FOUR GREAT MASTERS factsanddetails.com ; QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Painting” by James Cahill (Rizzoli 1985) Amazon.com; “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” by Richard M. Barnhart, et al. (Yale University Press, 1997); Amazon.com; “How to Read Chinese Paintings” by Maxwell K. Hearn (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008) Amazon.com; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Nature in Chinese Art

Serenity and tranquil beauty have traditionally been valued in Chinese culture and aesthetics. Fei Bo, a Chinese choreographer, told The Times: “Our culture is more about spiritual things, and nature is much more important to us. In our traditional painting the strokes are very simple but they leave a big space for your imagination.”

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In no other cultural tradition has nature played a more important role in the arts than in that of China. Since China's earliest dynastic period, real and imagined creatures of the earth—serpents, bovines, cicadas, and dragons—were endowed with special attributes, as revealed by their depiction on ritual bronze vessels. In the Chinese imagination, mountains were also imbued since ancient times with sacred power as manifestations of nature's vital energy (qi). They not only attracted the rain clouds that watered the farmer's crops, they also concealed medicinal herbs, magical fruits, and alchemical minerals that held the promise of longevity. Mountains pierced by caves and grottoes were viewed as gateways to other realms—"cave heavens" (dongtian) leading to Daoist paradises where aging is arrested and inhabitants live in harmony. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org \^/]

“From the early centuries of the Common Era, men wandered in the mountains not only in quest of immortality but to purify the spirit and find renewal. Daoist and Buddhist holy men gravitated to sacred mountains to build meditation huts and establish temples. They were followed by pilgrims, travelers, and sightseers: poets who celebrated nature's beauty, city dwellers who built country estates to escape the dust and pestilence of crowded urban centers, and, during periods of political turmoil, officials and courtiers who retreated to the mountains as places of refuge.\^/

“Early Chinese philosophical and historical texts contain sophisticated conceptions of the nature of the cosmos. These ideas predate the formal development of the native belief systems of Daoism and Confucianism, and, as part of the foundation of Chinese culture, they were incorporated into the fundamental tenets of these two philosophies. Similarly, these ideas strongly influenced Buddhism when it arrived in China around the first century A.D. Therefore, the ideas about nature described below, as well as their manifestation in Chinese gardens, are consistent with all three belief systems.\^/

Butterfly, symbol of joy

“The natural world has long been conceived in Chinese thought as a self-generating, complex arrangement of elements that are continuously changing and interacting. Uniting these disparate elements is the Dao, or the Way. Dao is the dominant principle by which all things exist, but it is not understood as a causal or governing force. Chinese philosophy tends to focus on the relationships between the various elements in nature rather than on what makes or controls them. According to Daoist beliefs, man is a crucial component of the natural world and is advised to follow the flow of nature's rhythms. Daoism also teaches that people should maintain a close relationship with nature for optimal moral and physical health.\^/

“Within this structure, each part of the universe is made up of complementary aspects known as yin and yang. Yin, which can be described as passive, dark, secretive, negative, weak, feminine, and cool, and yang, which is active, bright, revealed, positive, masculine, and hot, constantly interact and shift from one extreme to the other, giving rise to the rhythm of nature and unending change.\^/

“As early as the Han dynasty, mountains figured prominently in the arts. Han incense burners typically resemble mountain peaks, with perforations concealed amid the clefts to emit incense, like grottoes disgorging magical vapors. Han mirrors are often decorated with either a diagram of the cosmos featuring a large central boss that recalls Mount Kunlun, the mythical abode of the Queen Mother of the West and the axis of the cosmos, or an image of the Queen Mother of the West enthroned on a mountain. While they never lost their cosmic symbolism or association with paradises inhabited by numinous beings, mountains gradually became a more familiar part of the scenery in depictions of hunting parks, ritual processions, temples, palaces, and gardens. By the late Tang dynasty, landscape painting had evolved into an independent genre that embodied the universal longing of cultivated men to escape their quotidian world to commune with nature. The prominence of landscape imagery in Chinese art has continued for more than a millennium and still inspires contemporary artists.” \^/

Later when the learning process begins, the student is expected observe and copy his master. Students are supposed to hang on every word the master says and are supposed to do things exactly as the master does.

Chinese Symbols

Well-known symbols of prosperity and good luck are: 1) jade (protection, health and strength, See Art); 2) eggs (tranquility, fertility and good luck in Hong Kong); 3) a bearded sage (longevity or success on exams); 4) a lady bearing fruit (prosperity); 5) a gourd with spreading tendrils (fertility); 6) plump, lively boys (happiness and many sons); 7) bamboo, plums and pine trees ("three friends of winter").

Imperial symbols included the colors yellow and purple. The Emperor wore yellow robes and lived under roofs made with yellow tiles. Only the Emperor was allowed to wear yellow. No buildings outside those in the Forbidden City were allowed to have yellow-tiled roofs. Purple represented the North Star, the center of the universe according to Chinese cosmology.

The dragon symbolized the Emperor while the phoenix symbolized the Empress. The cranes and turtles associated with the Imperial court represented the desire for a long reign. The numbers nine, associated with male energy, and five, representing harmony were also linked with the Emperor.

Crane, symbol of joy

The most prominent animal symbols are: 1) cranes (peace, hope, healing, longevity and good luck); 2) turtles (long life, but a tortoise refers to a cuckolded husband and a turtle egg is the Chinese equivalent of a bastard); 3) carps (good luck, they are admired for their strength and determination to swim upstream, traits that parents want their children to have): 4) lions (good fortune and prosperity, stone lion gates guard temples and even shopping malls); 5) deer (wealth and long life); 6) horse (success); 7) sheep (auspicious beginning of a brand-new year); 8) monkey (success);

Fruit symbols: 1) orange (happiness); 2) many-seeded pomegranate (fertility); 3) apple (peace); 4) pear (prosperity); 5) peaches (long life, good health and sex, both Chinese and Arabs regard the fury cleft on one side of the peach as symbol of the female genitalia). Peach trees mean dreams can come true. Beginning in the 2nd century B.C., Taoist kept peach-wood charms to ward off evil. Sometimes handmade noodles are served on birthdays for long life.

Colors: 1) red or orange (happiness and celebration), 2) white (purity, death and mourning); 3) yellow and gold (heaven and the emperor, a reference the mythical first Yellow Emperor, sometimes yellow is a mourning color); 4) green (harmony); 5) grey and black (death and misfortune).

See Separate Articles: CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLSfactsanddetails.com DRAGONS AND AUSPICIOUS AND ARTISTIC SYMBOLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Chinese Landscape Painting

Unlike traditional Western painters, who used landscapes as background filler for battle scenes, portraits and central images of suffering religious figures, Chinese artists painted landscapes as the main subject matter. Religious, historical and mythological themes that were dealt with explicitly in the West were captured in the symbolism of trees, rocks, rivers, mountains and birds in the natural landscapes in Chinese paintings.

Landscape painting developed in the 4th and 5th century and became the most popular theme for painters beginning in the 11th century. While early figure painting was influenced by Confucianism, landscape painting found inspiration in Taoist thought. As it developed artists often sought inspiration more from artistic tradition than directly from nature. The painter-connoisseur Dong Qichang (1555-1636) wrote, "If one considers the wonders of nature, then painting does not equal landscape. But if one considers the wonders of brushwork, then landscape does not equal painting. "

Buddhism, Confucianism and early Taoism all emphasized the concepts of reclusiveness and communing with nature and this was reflected in landscape painting. Popular subjects such as mountains, streams, trees and mist were all prized for the transcendent freedom they inspired. Mountains usually come in two types: the rugged, steep, precipitous of northern China, or the misty, elegant, rolling mountains of the Kiangnan region in southern China.

Some landscape paintings are descriptive: an accumulation of painstaking details. Other are more emotional. Figures are mere specks that are primarily there to establish scale.

"All landscapes," wrote the 11th century critic Shen Kua, "have to be viewed from the angle of totality...to see more than one layer of the mountain at one time...see the totality of its unending ranges." In the early fourteenth century the philosopher Tang Hou wrote: "Landscape painting is the essence of the shaping powers of Nature. This through the vicissitudes of yin and yang — weather, time, and climate — the charm of inexhaustible transformation is unfailingly visible. If you yourself do not possess that grand wavelike vastness of mountain and valley within your heart and mind, you will be unable to capture it with ease in your painting.

Flower in Chinese Painting

Pink and White Lotuses

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Flowers, a major subcategory in the bird-and-flower genre, became the object of attention and depiction by painters throughout the ages. Artists not only directly portrayed the outer beauty of flowers, they also expressed the subtle spirit and demeanor of their subject. Painters went even further to imbue blossoms with deeper meaning, transforming them into objects for lodging feelings. As the Ming dynasty author Wang Xiangjin wrote in Record of All (Flowers) Fragrant, "I try to observe the morning flowers putting on their splendor, competing in all their great beauty and fragrance. Some keep company with others as they grow, while others go against time and show their preciousness. Despite their great floral beauty and exotic nature, such myriad manifestations are not easy to grasp. Their flourishing stems bloom and wither, also bringing joy and sorrow. Who says that such lodgings of joy and pleasantries of the heart are unrelated to the emotions and character?" [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Flowers in the collection of the National Palace Museum have been divided into four sections: "Beautiful Scenes All Year Round," "Formal Expressions of the Mind," "Their Many Features in Painting," and "Auspicious Signs and Lucky Omens." Flowers blooming throughout the year have been chosen to express their relation to the seasons and certain festivals in China. These artworks also demonstrate how artists used their skill of compositional arrangement and such basic techniques as ink outlines filled with colors, "boneless" washes, fine ink lines, and freehand "sketching ideas" to transform apparently simple subjects into a wide variety of forms and manners in keeping with the times. The interpretation of auspicious metaphors in paintings also reveals how artists portrayed blossoms from yet another point of view, allowing viewers to further appreciate the unique beauty and diversity of flower painting.

“Crape Myrtle Sketched from Life” by Song dynasty (960-1279) artist Wei Sheng is an ink and colors on silk album leaf, measuring 23.8 x 25.3 centimeters. Although Wei Sheng's dates are unknown, Xia Wenyan of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) in his Precious Mirror of Painting (chapter 4) has a short entry that states, "Wei Sheng: Extremely gifted at flower painting." It appears in his discussion of Southern Song (1127-1279) painters, suggesting that Wei was also an artist of that period. This work comes from "Album of Collected Song and Yuan Paintings." It shows an elegant branch of crape myrtle with blossoms of vivid color. This tree flowers in summer and its blossoms last for several months, hence its alternate name in Chinese as "Hundred-days red." It is an important flowering tree for appreciation in summer and autumn. In this work, a branch of crape myrtle extends into the composition from the lower left, the red blossoms and green leaves thriving with life. The centers of the blossoms appear like dense strands of silk forming tassels, the petals folded into delicate crinkles. Also, the full buds are oval-shaped, thus successfully capturing the unique features of the crape myrtle.

“Peony” by Ming Dynasty painter Xu Wei (1521-1593) is an ink on paper hanging scroll, measuring 133.3 x 34.5 centimeters. Xu Wei (style name Wenchang; sobriquet Tianchi; late sobriquet Qingteng laoren) was a native of Shanying (modern Shaoxing, Zhejiang). Inquisitive by nature, he excelled at paleography and diction, with his running cursive script calligraphy being most marvelous and painting in a style of his own. Xu Wei in his middle years began studying flower painting, his brushwork being naturally unrestrained and full of brilliant charm. This painting depicts peony and bamboo stalks in monochrome ink using the "sketching ideas" manner, presented them in a heroic and swift manner. The area of the flower petals clearly reveals light ink saturated with water, the brush then having been dipped in dark ink to complete the painting. It creates an intentional effect of ink halo gradations. The stalks and leaves of the bamboo were rendered with cursive-style calligraphic lines, the brushwork throughout being strong and swift, making this a work of great directness and energetic ease.

“Orchids and Bamboo” by Ming artist Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) is an ink on paper album leaf, measuring 19.7 x 54.2 centimeters. Wen Zhengming, a native of Changzhou in Jiangsu, excelled at poetry, painting, and calligraphy. In painting, he studied under Shen Zhou (1427-1509), the two of them becoming influential leaders in painting during the middle and late Ming dynasty. This work from "Painting and Calligraphy on Fans by Ming Officials" was originally done a folding fan of paper sprinkled with gold. "Hemp-fiber" texture strokes render a clump of serene orchids growing on a slope. The calligraphic lines were freely executed to depict the orchid leaves as they undulate naturally. The brush moved fluently yet with vigor, crisscrossing but not overlapping. Several stalks of bamboo were also added to the painting, making the composition dense but not overcrowded as both solid and void appear in harmony. The brushwork is both light and dark in places, adding to the variation and revealing a literati taste for pure untrammeledness and lofty elegance. Although undated, this work is similar to Wen Zhengming's "Orchids and Bamboo" hanging scroll painting from 1544, suggesting it was done sometime after his seventieth birthday. The two plants here are among the "Four Gentlemen," the bamboo also one of the "Three Friends of Winter" and a homophone in Chinese for "blessing." Hence, it is used in the expression, "Bamboo announcing safe and sound."

Animals and Birds in Chinese Painting

Animals were common subjects of Chinese paintings. But sometimes the animals featured were pretty unusual. “E-mo Bird” by Qing Dynasty artist Yang Ta-chang (fl. 18th century) — an ink and color on paper hanging scroll, measuring 149.8 x 101 centimeters, features a cassowary, a bird indigenous to Australia and New Guinea area. Yang Ta-chang, whose birth and death dates are unknown, served the court of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1795). The Qianlong Emperor, in his poetry and "Imperial Record on the Cassowary", wrote that this bird was not native to the West. He noted that its origins there began in 1587, when Dutchmen captured it on an island. Then it was purchased in India and presented to the king of what is now Portugal, ordering that detailed illustrations be done. The Qianlong Emperor also noted that apocryphal stories about the bird abounded. After he acquired one from a foreign ship in 1774, he refuted and/or re-examined these stories. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Kuo-jan (Lemur) from Cochi” by Lang Shih-ning (Giuseppe Castiglione, 1688-1766) is an ink and color on silk hanging scroll, measuring 109.8 x 84.7 centimeters of a lemur. This work, done in 1761, depicts a ring-tailed lemur (lemur catta) native to Madagascar. However, the Qianlong Emperor's inscription calls it a "kuo-jan" from Cochin (modern Vietnam), a tributary state of the Qing. Is it possible that a ring-tailed lemur originally from the western Indian Ocean was presented as tribute to the Qing court via Vietnam?

Often animal paintings had auspicious meanings. “A Hundred Deer of Prosperity” by an anonymous Ming dynasty (1368-1644) artist is an ink and colors on silk handscroll, measuring 45.6 x 290 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ At the scroll's beginning on the right are peaks and running water with pines and rocks shading the banks. Depicted there is a herd of deer frolicking, feeding, and resting in various poses, filling the work with great vitality. In the scenery are several leaf-clad youths picking spirit fungus and holding bamboo wicker baskets as they proceed through the hills. It is said that spirit fungus ("immortal grass") extends life. Here, "hundred" is also a term signifying "many" and the word for "deer" in Chinese a homonym for "prosperity." Meaning literally "great fortune," it is an auspicious theme conveying wishes for joy and good luck. This work is unsigned, but the subject and style suggest the hand of a court painter of the middle Ming dynasty. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Manual of Birds” by Yu Sheng and Chang Wei-pang (fl. 18th century) is a Qing Dynasty ink and color on silk album, measuring 41.1 x 44.1 centimeters. Composed of 12 albums with 30 leaves each, for a total of 360 works, the first four albums are in the National Palace Museum collection, and the latter eight are in the Peking Palace Museum. In 1750, the Painting Academy artists Yu Sheng and Chang Wei-pang were ordered to copy "Chiang T'ing-hsi's 'Manual of Birds'" in the court collection, taking 11 years to finish. The right side of each leaf is painted in fine-line brushwork with Western techniques for each bird. On the left is an inscription in Manchu and Chinese for the bird's name, description, features, native place, and habits. Thus, it is almost like a modern illustrated encyclopedia of bird species.

“In "Pair of Mandarin Ducks on an Autumn Bank" by the artist-monk Hui-ch'ung of the Song Dynasty, delicate brushwork was used by depict these waterfowl and their surroundings. In the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) representation of a mallard in Ch'en Lin's "Wild Duck by a Brook", he adopted the idea of the painter-calligrapher Chao Meng-fu (1254-1322) to "use calligraphy in painting" for a different approach. Thus, scenes of birds in remote wetlands often provided artists and viewers with an imaginary escape from urban life.

Song Dynasty (960–1279) Bird, Animal and Flower Painting

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “When the founding emperors of the Song defeated the courts of their rivals, they took over their court artists, who included some experts in bird and flower painting. From then on, this type of painting was a specialty of the court. “Magpies and Hare” is a large handscroll, perhaps originally part of a screen painting, painted by Cui Bo, active during the reign of Shenzong (r. 1067-85). [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“Very similar painting techniques were used by Li Anzhong, a court artist who began painting in the late Northern Song court but joined the Southern Song court as well after it relocated in Hangzhou. The birds and branches in Li Anzhong, "Bird on Branch" are details from a large hanging scroll, depicting several birds perched in the branches of an old plum tree or the bamboo next to it. The painting was probably done by artists serving under Huizong (r. 1100-1125). /=\

Famous Song era animal paintings in the National Palace Museum, Taipei collection includes: "Blue Magpie and Thorny Shrubs" by Huang Chü-ts'ai; "Magpies and Hare" by Ts'ui Po, Five Dynasties (Liang) and “Monkey and Cats” by I Yuan-chi. “Monkey and Cats” by I Yuan-chi, fl. 11th century is a handscroll, ink and colors on silk (31.9 centimeters x 57.2 centimeters): “In this painting, a pet kitten with a red ribbon collar is held in the clutches of a monkey. With a calm yet mischievous look, it is tethered to a stake in the ground. Perhaps the kitten was caught as it was passing by the monkey. The kittens were rendered with extremely fine brushstrokes to which was added washes of color, and the monkey was rendered in the same manner. The satisfied monkey, fearful captured kitten, and angry other kitten have all been captured and portrayed by the artist in the dramatic scene shown here. Frozen in naturalistic positions against a blank background, the spirit and appearance appear quite true to life. The realism here accords with the ideals of naturalism sought by artists of the Northern Sung (960-1126).[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

Night Revels by Gu Hongzhong (910–980)

Insects in Chinese Painting

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““One of the traditional subjects in Chinese painting is called "plants and insects", which refers to the specialized representation of insects (often with plants). This subject is related to and sometimes combined with two others in Chinese paintings — "birds and flowers" and "fruits and vegetables". What does it take to make a good "plant-and-insect" painting? One of the most important things is first to catch the insect one wants to depict and then raise it, allowing one to observe every detail of its appearance and movement. In addition, one must also study its behavior directly in nature. Only then, when taking up the brush, is one able to grasp every nuance associated with that particular insect. Throughout much of the history of Chinese painting, there have been many painters of "plants and insects" and the successful ones all seemed to have stressed this aspect in their works of art. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

The theme of plants and insects already reached a high level of naturalism by the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Representative works include Ts'ui Ch'ueh's "Seed-bearing Lycium and Quail," Wu Pin's "Insects and Abundant Grain," Hsu Ti's "Insects and a Cabbage Plant", and Li Ti's "Plants and Insects in Autumn". In the centuries that followed, some insect paintings were also done in a more sketchy style. Not only do such works suggest the quick movement of insects, but the spontaneous brushwork also echoes their fleeting existence in the natural world. Ming dynasty (1368-1644) paintings such as Sun Lung's "Sketch from Life" and Chu Hsien's "Plants and Insects" fall into this category. In addition, many representations of insects convey traditional wishes and blessings. For example, a common subject symbolizing the desire for a large family is the katydid and melon, which are known for their numerous offspring and seeds. Furthermore, the cricket sounds like a spinning wheel and therefore served as a symbol to remind people of the coming autumn and winter. Such examples reflect how the power of imagination linked the worlds of insects with Chinese art and culture.

“Insects and a Cabbage Plant” by the Song Dynasty artist Hsu Ti (12th century) is an ink and colors on silk album leaf, measuring 25.8 x 26.9 centimeters. Hsu Ti was a native of P'i-ling (Jiangsu province), a place noted for its plant-and-insect painters. Excelling at plants and insects, his style derives from that of the monk-painter Chu-ning. This leaf from the album "Collected Sung and Yuan Paintings" is quite simple in composition, showing only a cabbage plant, a crawling locust, and a white butterfly and dragonfly in flight. Each of these four subjects occupies a corner of the painting. Such an arrangement may be somewhat lifeless, but the superb refinement of the ink and color (creating for their detailed and naturalistic appearance) make this painting stand out.

“Katydids and a Melon Plant” by the Song Dynasty artist Han Yu Ti (12th century) is an ink and colors on silk album leaf, measuring 25.3 x 26 centimeters. Han Yu, a native of Jiangxi province, served in the painting academy of the Shao-hsing era (1131-1162) under Emperor Kao-tsung as a "chih-hou". Excelling at intimate scenes and flowers, and his representations of plants and insects followed in the style of Lin Ch'un. “This leaf from the album "Collected Sung and Yuan Paintings" shows a melon plant on the ground with some grass behind it. This luxuriantly blossoming plant bears a large ripe fruit that evidently has attracted the attention of two katydids. This kind of small melon has long tendrils and spreads over a large area, continuously bearing fruit. Likewise, the katydid is known as an insect that produces many offspring. Thus, when appearing in Chinese painting, they often convey the auspicious theme of wishing for many children.

“Silkworms Feeding on a Mulberry Tree” by the Ming Dynasty artist Wen Shu (1595-1634), is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 78.5 x 32.7 centimeters. Wen Shu, a native of Suzhou, was the great-granddaughter of the famous Suzhou artist Wen Cheng-ming. Gifted since childhood in painting, she made sketches from life upon coming across interesting plant-and-insect subjects, which are said to have totaled more than a thousand. This work depicts the branch of a mulberry tree bearing red fruit and luxuriant green leaves. Three silkworms are also shown here; one inches up the branch while two are munching on a leaf below. The holes in the leaves clearly show the remains of their meal (hence the title of this work). The delicate colors of the white worms, green leaves, and red fruit have all been cleverly arranged, imparting even further elegance to the graceful brushwork and forms.

“Admiral Butterflies Sketched from Life” by Ming Dynasty artist Ch'en Hung-shou (1599-1652), Ming Dynasty is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 76.9 x 25.8 centimeters. Ch'en Hung-shou, a native of Zhejiang, often used exaggerated forms in his paintings to create a sense of distortion to his style. For this reason, he became an innovative artist of the late Ming and influential in the arts at the time. In this work is a thistle shrub with two colorful admiral butterflies overhead. Despite the stark thorns of the shrub, the complementary red and green pigments give this work a sense of vibrancy and abundance. The two butterflies of different forms flutter effortlessly and in harmony. The details of their anatomy also complement the fine thorns. Despite the simple composition, the artist's exceptional attention to the arrangement and details make this a masterful work.

Fish in Chinese Paintings

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Throughout the course of Chinese history, many people have extolled the free and easy feeling of fish swimming leisurely in the water. During the Spring and Autumn period, for example, Duke Yin (ruler of the state of Lu) is recorded as having broken with protocol by insisting on visiting a frontier area just to appreciate how people catch fish. And from the Warring States era comes the “Debate on the Hao Bridge” between Zhuangzi and Huishi about “The Joy of Fish,” a story familiar to many. In ancient Chinese art, depictions of fish range from painted pottery of the Neolithic Age to silk painting of the Pre-Qin era and illustrated bricks and tiles of the Han dynasty. And by the twelfth century, the imperial Xuanhe Painting Catalogue had divided painting into ten subjects, one of them being “Dragons and Fish.” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“School of Fish Frolicking Among Water Plants” attributed to Liu Cai of the Song dynasty, for instance, shows fish swimming leisurely among plants. In “Cat with Fish and Aquatic Plants” by Shen Zhenlin of the Qing dynasty, the artist portrays a goldfish swimming to-wards a cat and oblivious to the danger. In terms of sheer skill in painting, Lang Shining (Giuseppe Castiglione) of the Qing dynasty, with his opaque colors and Western techniques, delicately expresses in his “Fish and Aquatic Plants” the surface sheen of fish and the volume of their features, placing this work squarely in the “sketching from life” tradition. Ma Hezhi’s “Clear Stream and Calling Crane” from the Song dynasty, on the other hand, represents the style known as “sketching ideas,” in which just a few strokes of the brush have been used here to suggest a school of fish flitting about the waters. Throughout the ages, Chinese paintings have not only portrayed images and actions of various kinds of fish, they also have often conveyed much auspicious meaning as well. For example, in the twentieth century, Qi Baishi in his “Great Prosperity for Many Years” depicted catfish and mandarin fish as an auspicious pun for the title, the names of these two fish in Chinese being homophones for “year” and “prosperity,” respectively.

“School of Fish Frolicking Among Water Plants”, attributed to the Song Dynasty painter Liu Cai (fl. ca. 11th century), is an ink and colors on silk handscroll, measuring 29.7 x 231.7 centimeters. This painting is unsigned, but a front section of silk on the mounting features an inscription that reads, “‘School of Fish Frolicking Among Water Plants’ by Liu Cai of the Song dynasty.” Liu Cai (style name Hongdao or Daoyuan) was a famous painter of fish in the Northern Song dynasty. Xuanhe Painting Manual describes his depictions of fish as swimming naturally about, as he was gifted at showing fish frolicking in the depths and lost in the joy of rivers and lakes. Later genera-tions came to associate paintings of fish and water with Liu Cai, thereby enhancing his reputation even more.

“This painting depicts ripples above the bottomless water, the plants in limpid waters rendered with an illusory effect using light ink. The fish swim among the plants in a leisurely manner. The artist used the method of rendering the fish darker than the aquatic plants to create a layered effect. Alt-hough this is actually a Ming dynasty painting, it nonetheless retains the spirit of Liu Cai’s depiction of “breezes, water plants, and fish all in a lively manner.”

“Fish with Aquatic Plants” by an anonymous Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) artist is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 141.9 x 59.6 centimeters. As early as the Song dynasty Xuanhe Painting Manual from 1120, “Dragons and Fish” was already considered an independent category in painting. This hanging scroll depicts plants on the water surface along with other aquatic vegetation that sug-gest an underwater scene. From top to bottom, three fish large to small have been arranged in order. They were first done by outlining the forms in light ink and then building up the scales and fins with layers of washes. The largest one at the top, a mandarin fish, was done using not only brush and ink to describe its unique characteristics but also a coarse cloth soaked in ink and dabbed on the upper surface, giving the delicate scales an even more animated and realistic effect. The water plants also were skillfully rendered to give the painting an overall decorative quality as well.

Detail of Night Revels by Gu Hongzhong (910–980)

Figures in Chinese Painting

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The human figure as a subject in Chinese painting appeared well before such later popular ones as the landscape or birds-and-flowers. The purpose behind the painting of figures in early times was mostly to serve religious or political aims. Archaeological discoveries of paintings on silk and on tomb and cave walls so far offer a glimpse at the development of figure painting from the Spring and Autumn (722-481 B.C.) to Warring States (403-221 B.C.) periods, to the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-220 CE), and into the Wei and Jin era (265-420). Unfortunately, paintings on silk and paper, due to their fragility, are difficult to preserve, so almost all of the authentic works by such famous figure painters of the Jin and Tang dynasty (618-907) as Gu Kaizhi (ca. 344-405) and Wu Daozi (ca. 685-758) have long since disappeared. Of the many masterpieces of figure painting in the National Palace Museum collection, for example, only “A Palace Concert” can be considered as representative of the late Tang era. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Starting from the Song dynasty (960-1279), however, the number of authentic works in circulation gradually increased. There was no lack to the detailed fidelity and colorful finesse of figural compositions in various themes and formats, including historical narrative illustrations reconstructing ancient scenes, genre works reflecting the life of commoners, depictions of beautiful ladies, and portraits of personages in painting and poetry modeled after literary works. There were even sketchy and unbridled Chan (Zen) paintings of figures that made their appearance at this time. Shining examples of Song figure painting include Zhang Zeduan’s (1085-1142) “Up the River on the Qingming Festival,” Su Hanchen’s (11th-12th century) “Children at Play in an Autumnal Garden,” Mou Yi’s (1178-?) “Making Clothes,” and Liang Kai’s (13th century) “Immortal in Splashed Ink,” which all had a profound influence on later developments in figural art.

An exhibition at the National Palace Museum, Taipei focused primarily on the rich and beautiful variety of figure and genre painting from the Yuan (1279-1368), Ming (1368-1644), and Qing (1644-1911) periods. The selection of sixteen sets of works on display includes Wang Zhenpeng’s (fl. 1280-1329) “Dragon Boat Race by the Baojin Hall,” Tang Yin’s (1470-1524) “Imitating a Lady Painting by a Tang Artist,” Qiu Ying’s (ca. 1494-1552) “Orthodoxy of Rulers Through the Ages,” Wu Bin’s (16th-17th century) “Record of Annual Events and Activities,” Leng Mei’s (fl. 17th-18th century) “Illustrations of Agriculture and Sericulture,” and Yang Dazhang’s (fl. 18th century) “Imitating a Painting of Jinling by Song Court Artists.” Popular works such such as “A Palace Concert” by a Tang artist, Qiu Ying’s “Spring Morning in the Han Palace,” and “Up the River on the Qingming Festival” by Qing court artists are too fragile to display.

“Dragon Boat Race by the Baojin Hall” by Wang Zhenpeng (ca. 1280-1329), Yuan dynasty, is an ink on silk handscroll, measuring 36.6 x 183.4 centimeters. Wang Zhenpeng (style name Pengmei) was a native of Yongjia, Zhejiang, and given the sobriquet Guyun chushi by Emperor Renzong (Buyantu Khan; r. 1311-1320). He was Archivist in the Imperial Library and rose to Grain Transport Officer, but he was best known for his ruled-line painting. “This work depicts the Northern Song (960-1127) emperor at Jinming Pond in Kaifeng on the Qingming Festival, as recorded in Dream Journey to the Eastern Capital. It shows him watching the forces and merriments along with a dragon boat regatta. The inscription at the end indicates this work was done in 1310. Wang Zhenpeng used fine, complex lines to precisely delineate the palatial structures and boats of all sizes, also depicting raucous genre scenes of merriment, making this a masterpiece of Yuan dynasty ruled-line painting.

“Peddling in Spring Scenery” by an anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) artist is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 196.8 x 104.3 centimeters. Peddling in Spring Scenery Peddler scenes became popular in Chinese art starting in the Song dynasty (960-1279). This work (with no seal or signature of the artist) depicts a countryside scene with peach blossoms just opening and willow branches of newly sprouted leaves as grasses flourish by a small stream. The peddler has rested the openwork display of goods with many kinds of caged birds and also toys. Of the two peddlers, the one in front offers a parrot to the elegantly dressed lady with two children. With hand raised, the youngest child moves forwards with joy as if to ask for the bird. The figures’ coloring is beautifully elegant, and the details of their clothing and other motifs are refined. The spirited, lively figures accentuate this leisure scene from traditional China.

“Literary Gathering in the Western Garden”, attributed to the Yuan Dynasty artist Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) is a is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 131.5 x 67 centimeters. This subject is about a banquet gathering of the famed Northern Song scholars Su Shi, Huang Tingjian and eight others at imperial son-in-law Wang Shen’s garden home. The work shows them in five groups around Su Shi, Li Gonglin, and Mi Fu doing calligraphy, painting, and bowing to a stone, respectively. Chen Jingyuan is also playing the ruan and Liu Jin talking with Master Yuantong. Many versions were done over the ages.

“Ning Qi Feeding an Ox” by Ming Dynasty artist Zhou Chen (ca. 1460-after 1535) is an ink on paper hanging scroll, measuring 126.7 x 68.9 centimeters. Zhou Chen (style name Shunqing, sobriquet Dongcun) was native to what is now Suzhou, Jiangsu. He specialized in landscapes and figures, achieving the brush method of earlier Song dynasty painters. Whether in the fine-line or sketching-ideas styles, all have a character of their own. “Ning Qi, a native of Wei in the Spring and Autumn period (second half of the 8th century-first half of the 5th century B.C.), pulled a cart to make a living due to the poverty of his family. In the state of Qi, he one day came across Duke Huan, who was on an inspection tour. Ning Qi was feeding his ox and tapping its horns as he sang. The duke felt this was no ordinary man and summoned him, later making him Counselor-in-chief. The work here shows Ning Qi holding a stick as he feeds the ox. The brushwork is strong and sharp, the vines on the old tree unusually dynamic like the horns of a dragon.

“The Knick-knack Peddler”

“The Knick-knack Peddler” by Song Dynasty artist Li Sung (fl. 1190-1264) is an ink and light colors on silk album leaf, measuring 25.8 x 29.6 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Li Sung, a native of Hangzhou, is said to have started his career as a carpenter. He came to the attention of the court artist Li Ts'ung-hsun, who adopted the youth and passed on his skills as a painter to him. In the process, Li Sung learned to master many subjects, including figures, landscapes, and flowers. Many figure paintings associated with him involve scenes of daily life (in or out of the court), pasturing, or his famous peddlers accompanied by children — this work being one of his most famous examples. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The peddler has numerous items in a scene that must have been common in the countryside. The artist has captured the vivid excitement of children catching sight of the peddler's toys. The vendor has put down his pole loaded on both ends with hundreds of objects as he beats a small gong to advertise his wares. He appears to see a child about to grab something as this once quiet setting has suddenly become a raucous scene.

“At the left side is the signature, "Painted by Li Sung in the keng-wu year of the Chia-ting era [1210]." Not far below, on the tree trunk, is another inscription in three characters that reads, "Five-hundred items." Whether this number was meant literally or figuratively, it seems that the artist almost tempts the viewer to stop and count the items. Presented are a vast array of everyday objects. In addition to many tools and utensils are medicinal herbs and edibles, such as preserved vegetables and dumplings. To the children's delight, he also has many toys, including kites, gourds, bow and arrow, flags, a puppet alligator, and figurines. For entertainment or for sale, he even has animals, such as a trained wagtail and mynah. Some of the objects and services are also identified by labels. The presence of some items and characters, for example, suggest that the peddler offered spiritual services. A sign on one of his hats reads, "Skilled at curing oxen, horses, and children." The emphasis in this work was clearly directed towards the children and these "five hundred items."

“One of the features of this painting is the rendering of the drapery lines. Li Sung accurately suggests the folds of these rough clothes. As seen in the matron's robes, the lines start with so-called "nail-head" strokes, which then bend back and forth before reaching a long, slender point known as a "rat-tail" stroke. This combination became a trademark of the Li Sung style of village folk as he departed from upper-class taste and rendered the life of common people.

“The Knick-knack Peddler”

Tang Yin: Great Figure Painter of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

Painters such as Du Jin, Zhou Chen, Tang Yin, and Qiu Ying were active stood out as some of the finest professional painters of the age. The figure painting of these four artists is marked by elegant forms and beautiful scenery. In addition to a fine style with colors, they also had a more unrestrained one dominated by ink. Although they inherited from the refined academic style of the Tang and Song Dynasties, they also fused it with the warm and personal manner of literati artists, creating a point of convergence with the literati Wu School of the period.

Tang Yin (1470-1523) is regarded as one of the best figure painters in China of all time. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “A native of Suzhou, he studied under Zhou Chen, but later turned to the Sung and Yuan styles, taking the delicate and refined techniques of the Southern Sung academic mode and fusing them with the pure and elegant style of Yuan artists. Forming a manner of his own, he was known as one of the Four Masters of the Ming. From the middle of his career, he developed his own style. Fusing the academic and literati modes, the forms he painted were solid yet done with elegant brushwork. The compositions of his works were straightforward yet expansive, possessing a lyrical quality. His brushwork was both strong and soft, which in later years became flowing and abbreviated.

Tang Yin (style names Bohu, Ziwei; sobriquet Liuru jushi) was a talented genius who was also unrestrained and unconventional. Though placing first at the Nanjing provincial exams, he was later implicated in a scandal, ending his prospects as an official. Studying painting under Zhou Chen, he early achieved renown in landscape, figure, and bird-and-flower subjects. “The Lutanist” by Tang Yin is an ink and light colors on paper handscroll, measuring 29.2 x 197.5 centimeters. In this handscroll a scholar sits lightly playing the lute among rocks, pines, and water with books, an inkstone, bronzes and curios around him in an elegant scholarly manner. A gurgling stream also seems to accompany the music. The musician is Yang Jijing (Ling), a native of Wu. Known for his talent with the lute, Tang Yin painted him twice, this work being one of them.

“T'ao Ku Presenting a Lyric to Ch'in Jo-lan” by Tang Yin is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, 168.8 x 102.1 centimeters. In the early Sung (960-1279), T'ao Ku (903-970) was Minister of Revenue who served as envoy to the small Five Dynasties kingdom of the Southern Tang. T'ao was condescending to the Southern Tang ruler. The Southern Tang officials, angered by his rudeness, came up with a plot to send the courtesan Qin Jo-lan in the guise of the Station Officer's daughter to seduce T'ao. Alone in her company and unsuspecting of her identity, T'ao Ku was overcome by her beauty and neglected his official position, indiscreetly writing a poem for her. The next day, the Southern Tang ruler gave a banquet for T'ao. At the banquet, T'ao again assumed an air of unbending dignity and unapproachability. The ruler then summoned Qin Jo-lan to perform a song based on the poem that T'ao had written for her the day before. T'ao was thereupon humiliated and lost his composure.

“Lofty Scholars” by Tang Yin is an ink on paper handscroll, measuring 23.7 x 195.8 centimeters. Shown first here is a child attendant with hands clasped. Next to a round stool is a straw mat with paper, brush, book, inkstone, and other objects. In the center, three lofty scholars converse against a backdrop of trees, rocks, and moss clumps. The marvelous brushwork is forceful, combining light and dark ink. At the end of the scroll is a stone table with a jar and an unrolled scroll of paper.

Women Figures in Chinese Painting

“Ladies” by Jiao Bingzhen (17th-18th century) is an ink and colors on silk album leaf, measuring 30.9 x 20.4 centimeters. Jiao Bingzhen, a native of Jining, Shandong, served in the Directorate of Astronomy and came in contact with Western painting. His depictions of figures and palatial buildings were influenced by Western methods of shading. “This album consists of eight leaves, of which four are on display here. The ladies appear in different seasons and engaged in various leisurely activities. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Gathering Gems of Beauty” by Qing dynasty (1644-1911) artist He Dazi is an ink and colors on silk album leaf, measuring 30.1 x 22.5 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ Each of the twelve leaves in this album has a title and depicts such famous beauties in Chinese history as Xi Shi, Qin Luofu, Qin Longyu, Madame Li of the Han, Zhuo Wenjun, Cai Wenji, Wu Liju, Princess Shouyang, Mulan, Madame Gongsun, Hongxian, and Lady Hongfu. The painter is identified as He Dazi, perhaps a Painting Academy artist whose style followed Jiang Bingzhen’s ladies, but whose birth and death dates are unknown. The left leaves have transcriptions of lines of ancient poetry by the court official Liang Shizheng from 1738 related directly or indirectly to events of the ladies depicted in the paintings. Though the works follow in the style of court lady painting, the lines of verse reveal different facets in praise of feminine virtues.

“Refusing the Seat” by an anonymous Song dynasty (960-1279) artist is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 146.8 x 77.3 centimeters. This work depicts an event from the reign of the Han emperor Wendi. One day he and his empress and consorts went to Shanglin Garden, where the upright official Yuan Ang remonstrated that Lady Shen could not sit by the ruler. The work shows a garden with the emperor and empress as well as Lady Shen refusing the seat. The emperor listens to Yuan intently, the work focusing on the ruler and subject and expressing the idea of orderly court relations — the ruler open-mindedly accepts remonstration as officials offer advice based on reason and consorts act according to protocol, serving as a paragon for later generations. The figure lines are fluent and succinct, the delineation of trees and rocks fine and exact, suggesting a style close to that of the Southern Song (1127-1279).,

Tang Yin Women

A beautiful Woman by Tang Yin

“Imitating a Lady Painting by a Tang Artist” by Tang Yin is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 149.3 x 65.9 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ “The subject of this lady painting comes from the story of the courtesan Li Duanduan seeking a lyric from the poet Zhang You (?-ca. 853). In it, Li Duanduan is shown holding a white peony blossom and standing upright by a screen. Zhang You sits on a daybed and concentrates, as if composing the line that made Li famous, “…a peony blossom able to walk along.” The line and image here thus seem to match flawlessly. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Tao Gu Presenting a Verse” by Tang Yin is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 168.8 x 102.1 centimeters. Tao Gu here sits on a daybed twisting his beard and listening to a song. Next to him is a brush and inkstone, and in front is a candle. A young lady with embroidered topcoat and hair tied sits opposite him playing a pipa. Tao, also active in the Five Dynasties period, later became Minister of Revenue in the Song dynasty. On a trip to Jiangnan he met the courtesan Qin Ruolan. Mistaking her as the stationmaster's daughter, he let down his guard and gave her a verse, a breach of official etiquette. The next day, the Southern Tang ruler held a banquet for Tao, who assumed an air of unapproachable aloofness. The ruler, having laid a trap for him, held up a wine cup and asked Qin Ruolan to sing Tao's verse, much to Tao's shame and demise as an official. Here he is shown at the station with Qin Ruolan.

“Concubine Ban's Rounded Fan” by Tang Yin is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 150.4 x 63.6 centimeters. This work derives from Ban Jieyu's "Song of Reproach," in which she wrote, "Ever fearful of autumn's arrival, when cool breezes quench the sizzling heat, you will discard your fan into a box, your affection suddenly stopping." Under coir palm trees, Concubine Ban stands here holding a fan in a courtyard with hollyhock in front, signaling the end of summer. The blossoms are in the "boneless" wash technique, while her face reveals makeup known as "three whites."

Narrative Figures in Chinese Art

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““In China, certain events surrounding legendary figures, wise sages, famous officials, and rulers of old are not only recorded in texts, but also have been transmitted to later generations in the form of illustrations. The medium of painting, for example, allows audiences to easily grasp the content of a story by means of its concrete pictorial representation. When the written record is interpreted through the mind and hand of the painter, a reciprocal relationship is formed between the image and text of history and legend. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“No one knows when the first narrative figure painting was done, but it is said that the royal ancestral temple (Ming tang) of the Zhou dynasty (11th century-221 B.C.) court was already decorated with wall paintings of historical subjects. Furthermore, some surviving Western Han (206 B.C.-8 CE) wall paintings also deal with themes from history and legend. With the rise of Confucianism as the foundation of state during the Han dynasty, painters who worked for government agencies or the court often illustrated stories from history and legend to serve didactic or moralistic purposes. By the Six Dynasties period (220-589), Daoist thought rose in popularity and broke from the confines of Confucianism, resulting in an increase in the number of deities and immortals portrayed along with Buddhist and Daoist figures as well as narrative paintings on literary themes. With the unification of the country in the Tang dynasty (618-907), China's power rose to new heights and emperors valued the didactic function of art. Court artists were often commissioned by their rulers to eulogize meritorious officials by portraying them or recording important historical events. In the Five Dynasties and Song period (from the 10th to 13th centuries) techniques for depicting landscapes, trees, and bird-and-flower subjects matured and were fused with narrative figure painting. With figural forms, compositional designs, and background arrangements set off in a new-found sense of atmosphere, painters were able to create even more precise and complex works. With the fall of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) and into the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911), many stories became quite familiar to audiences, so representations of plot detail and figural expression gradually declined as artists and audiences focused instead on stylistic features.

“Narrative figures generally fall into three categories: "Stories from History," "Stories of Deities, Immortals, and Daoists," and "Stories from Buddhism." The first deals with didactic historical themes meant to educate or admonish, such as Bian Zhuangzi killing tigers, Yu the Great controlling floodwaters, and Concubine Ming leaving China. There are also tales and anecdotes of famous scholars or literary subjects, such as "Returning Home," "Pavilion of the Old Drunk," "Literary Gathering in the Western Garden," "Searching for Verse on Ba Bridge," and "Han Xizai's Night Revels."

“Returning Home”, a attributed to Lu Tanwei (420-479), Six Dynasties period is an ink and colors on silk handscroll, measuring 43 x 142 centimeters. Tao Yuanming (365-427) decided not to be a slave to his official's salary of five pecks of rice, so he left office and wrote "Returning Home" to express his rustic ambitions. This work depicts the first part of this literary classic ("Let me return! My fields will become wasteland.") to "The paths had weeds, but the pines and chrysanthemums were still there." Here, Tao has picked his favorite flower, the chrysanthemum, and is in a boat as family members come out to greet him, depicting "Lightly the boat swayed back and forth" and "Welcoming servants came out as the children waited at the gate." Lu Tanwei was a painter of the Liu-Song era who excelled at figure and narrative subjects. The style of this work, however, probably dates to the thirteenth century or later.

Fanghu Island

of the Taoist immortal

“Bian Zhuangzi Stabs a Tiger”, by an anonymous Song dynasty (960-1279), is an Ink and light colors on silk handscroll, measuring 39 x 169.1 centimeters. This work shows an injured ox and two tigers fighting over it. The official Bian Zhuangzi of Lu in the Spring and Autumn Period (770-221 B.C.) was renowned for bravery. Taking out a sword to kill a tiger, his attendant told him that when two tigers fight, one will die and the other will be injured. He could then wait, easily kill the injured tiger, and thus claim to have killed both of them. Bian thus took the advice. At the end of the scroll, Wang Shu wrote that it reminded him of "The snipe and clam grapple" (so the fisherman wins). Thus, he warns not to think of oneself by taking advantage of the weak, but to come to others' assistance. This work is not signed, but the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) court attributed it to Li Gonglin (ca. 1049-1106). The actions and appearance of Bian Zhuangzi and the tigers are quite animated.

“Zheng Yuanhe”, by Zhu Henian (1760-1834) is a hanging scroll, ink and light colors on paper, measuring 84 x 30.6 centimeters. The "Tale of Li Wa" from the Tang dynasty tells of the scholar Zheng Yuanhe, who went to the capital in the Tianbao era (742-755) to take the civil service examinations. However, he became infatuated with the courtesan Li Wa and splurged all his money on her, thus becoming a destitute singer-beggar. One day during a blizzard, Zheng was starving as he begged in the snow but was saved by Li Wa, who helped him return to studying and earn his degree. The figure appearing here has a disheveled cap, wears different shoes, and holds an instrument, showing Zheng as a singer-beggar.

“Auspicious Omens”, attributed to Song Dynasty artist Li Song (1170-1255), is an ink and colors on silk handscroll, measuring 33 x 96.8 centimeters. The early Southern Song (1127-1279) official Cao Xun once compiled stories of the auspicious omens that predicted the assumption of the throne by Emperor Gaozong (r. 1127-1162) into twelve sections, which were illustrated by the Academy painter Xiao Zhao. The twelve omens are 1) "Golden Aura at Birth," 2) "Xianren's Dream of a Deity," 3) "Archery and Lifting," 4) "Envoy to the Jin," 5) "Four Deities Protecting," 6) "Visiting a Cizhou Temple," 7) "Game Pieces in a Yellow Bag," 8) "Deceiving the Enemy," 9) "Shooting a Tower Plaque," 10) "Shooting a White Rabbit," 11) "Crossing a Frozen River," and 12) "Dream of Removing the Robe." This handscroll painting illustrates the fourth, fifth, ninth, and eleventh sections. Although attributed to Li Song, it is actually a Ming dynasty (1368-1644) copy instead.

Taoist Paintings

Taoism had a major influence on Chinese art forms such as painting, ritual objects, sculpture, calligraphy and clothing. Themes include rituals, cosmology and mountains. Birgitta Augustin of New York University wrote: “Daoist art reflects the broad timespan and the diverse regions, constituencies, and practices of its creators. The artists—commissioned professionals, but also leading Daoist masters, adepts, scholar-amateurs, and even emperors—working in written, painted, sewn, sculpted, or modeled media, created an astonishingly eclectic body of works ranging from sublime evocations of cosmic principles to elaborate visions of immortal realms and paradises as well as visualizations of the Daoist pantheon, medicinal charts, and ritual implements. [Source: Birgitta Augustin Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Chinese painting was greatly influenced by Taoism, a mystical religion-philosophy based on the principal that following the rhythms of nature are key to reaching heaven. The Tao tradition brought together past and present, nature and art, and poetry and painting. The best Tao-influenced Chinese art was defined as "divine class" or "marvelous class," terms that describe works by painters who developed their individual capacities to reveal the spirit of heaven and nature found in everyone.” [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

One of its most important goals of Taoist painting was revealing qi, variously known as the "Breath of Heaven," the "Breath of Nature" or the "Quality of Spirit." According to one painting manual, "qi is as basic as the way [people] are formed and so it is with rocks, which are the framework of the heavens and of earth, and also have qi. That is the reason rocks are sometimes spoken of as 'roots of the clouds.' Rocks without qi are dead rocks, as bones without the same vivifying spirit are dry bare bones. How could a cultivated person paint a lifeless rock...rocks must be alive."

Taoist painting often contained heavenly deities, roaming immortals, guardian figures and protectors of the faith. These images helped propagate Taoism by informing illiterate people though images rather than texts.

Among the popular subjects of Taoist paintings are the Eight Immortals, Liu Hai and his golden three-legged toad, deities on flying dragons, guardian figures, protectors of the faithful, "The Three Purities" (three important Taoist deities roaming through heaven), and "Three Officials on an Inspection Tour" (deified officials of heaven, earth and water on a procession through the clouds, land and water). Immortality was a central element of Taoism. Famous Taoist painting dealing with immortality include “Immortal Ascending on a Dragon”, “Riding a Dragon”, “Fungus of Immortality”, “Picking Herbs”, and “Preparing Elixirs”.

See Separate Article TAOIST ART factsanddetails.com

Ghost Paintings

Luo Ping was an 18th century Chinese artist who specialized in rendering ghosts. Yale historian and China expert Jonathan D. Spence wrote: “Luo Ping was not only innovative in “portraying” his ghosts with such specificity, he kept the element of surprise constantly to the fore...In the third section of his Ghost Amusement portrayed an absorbed amorous couple in unmarred human form, gazing into each other's eyes, while a man in the tall white hat of the underworld's guardians prepared to lead the couple into the netherworld. The woman's bared red shoes offered the viewer a signal that was, for the times, shockingly erotic. After four more panels of the magically displayed ghost figures, the eighth and final panel would have come with a startling force to the unprepared viewer — as two complete skeletons were portrayed standing tall and opposite each other in a clump of bare trees, dark rocks, and wild grasses. The precisely delineated specificity of these figures did not convey an auspicious message, but instead closed the scroll on a somber more than a mysterious note.”[Source: Jonathan D. Spence, New York Review of Books, in connection with Eccentric Visions: The Worlds of Luo Ping (1733-1799): an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, October 6, 2009; January 10, 2010]

Luo Ping ghost painting In one series of Luo Ping scrolls he art historian Yeewan Koon wrote: “Half naked with bald pates and small swollen stomachs, the two figures also recall the world of hungry ghosts, one of the Buddhist realms of existence. But the human emotions on the faces of Luo's ghosts place them in a gray consciousness that lurks between the real and the otherworldly. In this painting, Luo has created an ethereal existence by making his ghosts both strikingly familiar, through their human pathos, and evocatively strange,through their physical deformities.

Koon wrote: “The second leaf is a contrast of types: a skinny, bare-chested ghost with an official's hat follows a fat, bald ghost in tattered clothes against an empty background. The oscillation between specificity of types and ambiguity of situation allows room for a range of interpretations; some viewers were prompted to read this scene as phantasmagoric social commentary. [One scholar], for example, a Hanlin academician and playwright, described the figures in leaf 2 as a ‘slave ghost” and his master, whom he then compared to corrupt Confucian officials.

This “urge to rationalize the ghosts as allegories of human behavior,” adds Koon, “is derived in part from the theatrical immediacy of the images,” and in this sense the ghost paintings catch the tensions and contrasts that were coming to dominate this time in China's history — as well as the layers of religious euphoria that lay behind the alternate reading of the scrolls title as a “realm of ghosts,” a literalness of interpretation that Luo Ping deliberately fostered by his repeated claims that he had seen the ghosts in person on many occasions. This claim, writes Koon, was a part of Luo Ping's “invented persona as an artist who saw and painted ghosts,” a persona that ‘set him apart in a capital teeming with talent.”

See Separate Article CHINESE PAINTINGS OF GHOSTS AND GODS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikipedia, University of Washington; 3) Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html, China Beautiful website, Palace Museum, Taipie;, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Shanghai Museum. Luo Ping ghost painting from the Met in New York, Nelson-Atking Museum, Ressel Fok collection, Shanghai Museum.

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021