ART DURING THE SHANG DYNASTY

Shang ritual bronze

By around 1200 B.C. artisans were able to cast large bronze pieces, technology that wasn’t achieved in the Mediterranean for another thousand years. The Shang added lead to the mixture of tin and copper and developed a sophisticated casting process than allowed them to cast bigger and bigger bronze objects. The largest Shang vessel every discovered weighed 1,900 pounds. According the Oxford University Jessica Rawson, "the diversity of decorative motives on the bronzes indicated that influence of or manufacture by neighboring, contemporary societies of some sophistication."

During the Shang dynasty and Zhou dynasties jade objects were important objects in ceremonies and rituals. Shang Dynasty circular jades are generally similar to northwestern circular jades. Late Shang pieces featured raised inner rims and thin outer edges, sets of carved concentric circles and images of curling dragons, fish, tigers and birds. The Shang also made monster-face amulets with turquoise-inlay mosaics of swirls and eyes, marble part-tiger-part-human monsters.

Some of the oldest works of art from China are bronze vessels. The oldest ones date back to the Xia dynasty (2200 to 1766 B.C), when the legendary Yellow Emperor is said to have cast nine bronze tripods to symbolize the nine provinces in his empire.

Most ritual bronze vessels date back to the Shang Dynasty and the Zhou Dynasty (1122-221 B.C). These bronze vessels included elaborately-decorated caldrons, wine jars and water vessels that were used to offer food and drink to spirits, gods and deceased ancestors in political and spiritual ceremonies and rituals. Shang ritual vessels including ding caldrons, used to ritually prepare food for royal ancestors; Lei, large elaborately decorated vessels used to store wine; and yu basins, which may have been used to boil water or steam food.

Bronze vessels symbolized rank and often contained references to ancient imperial ethos, culture and music. One of the National Palace Museum's most prized bronze pieces is a yu wine container from the 11th century B.C. Another beautiful bronze piece is an 8th century B.C. water vessel, used for ritual offerings, with animal-shaped handles and legs in the form of human figures. Scholars believe the bronze vessels were likely copies of ceramic vessels. A fine white pottery was made during the Shang Dynasty. Many ceramic vessels were similar in size and shape to bronze vessels made during the same period.

Bronze vessels often bore inscriptions that said “This container has been made to commemorate” so and so and were often given as presents to officials from leaders as rewards. Many ancient bronzes were removed from China, especially in the early 20th century, and few have been given back or carefully studied.

Bronze vessels and figures were generally made using the lost wax casting technique, which worked as follows: 1) A form was made of wax molded around a piece of clay. 2) The form was enclosed in a clay mold with pins used to stabilize the form. 3) The mold was fired in a kiln. The mold hardened into a ceramic and the wax burned and melted leaving behind a cavity in the shape of the original form. 4) Metal was poured into the cavity of the mold. A metal sculpture was created and removed by breaking the clay when it was sufficiently cool.

See Separate Article SHANG DYNASTY ART: BRONZE AND JADE factsanddetails.com ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com

Art During the the Zhou and Qin Dynasties

During the Zhou Dynasty (1100-221 B.C.) jade pendants were very popular and the level of their craftsmanship was unmatched in any future period. Circular jades made during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States period (722-221 B.C.) were smaller than those from the Shang and early Zhou periods. They contained carved images of curling chih dragons, grain seeds, and cloud patterns. During this period circular jades were commonly worn by people. Materials other than jade, such as agate and glass were used to make "jade" ornaments.

Great works of art from the Warring States Period include bronze vessels with inlaid geometric silver decorations, snake-shaped bronze fittings and jade and gold wire jewelry and bows made with dragons with glass eyeballs.

See Separate Article ZHOU DYNASTY ART: BRONZE, JADE AND LACQUER factsanddetails.com

Emperor Qin's Tomb and the Terra Cotta Army

Perhaps the greatest work of ancient art was the tomb of Emperor Qin Shihuang Di. According to a 1st century B.C. historian chronicled in Ming-era records, the tomb contains a throne room, a copper dome, models of pavilions and palaces filled with gold, gemstones and other treasures, sacred stone tablets, copper coffins, inscribed soul towers, prayer temples, and a relief map of China with a miniature ocean and models of the Yangtze and Yellow rivers filled with flowing mercury.

The Emperor is said to have been dressed in jade and gold with pearls in his mouth, his coffin floating on mercury. Around the Emperor's body were vessels with precious stones and relics. The floor was inlaid with gold and silver ducks. The ceiling of the copper dome featured a starry sky of pearls and gems, and constellations made from candles made of whale oil, which burns longer than normal wax. To keep intruders out, the tomb was protected by crossbow booby-traps that shot anybody who tried to enter. The entire sanctuary has a circumference of nearly two miles.

The terra-cotta Army of Emperor Qin with 10,000 life-size figures was found in three massive pits near the tomb. Most of the figures are armed warriors, meant to accompany to Emperor Qin to the after-life and protect him in heaven from his enemies.

The terra-cotta soldiers are amazingly life-like and detailed. Each one has an individual face, and its own hairstyle and facial expressions. Some look savage; some look serene and composed; others look bold and self-assured; a few look like they are about ready to crack a smile. A name, possibly from an artist or maybe of a soldier, is stamped on the neck of every soldier. Some scholars believe each terra-cotta soldier is a facsimile of a real soldier in Qin's army.

See Separate Articles TOMB AND PALACE OF EMPEROR QIN SHI HUANG factsanddetails.com TERRA COTTA ARMY OF EMPEROR QIN SHIHUANG factsanddetails.com

Art During the Han Dynasty

Objects unearthed from Han-era tombs include gilded silkworms; stones with humans battling bears; golden belt buckles with a bear ad a tiger devouring a horse; bronze incense burners held by an image of an immortal; horned terra cotta heads used to ward off evil; and pear ornaments with girls holding lamps that would show the way to the afterlife.

Perhaps the greatest testimony of Han dynasty artistic achievement and skill was the "Flying horse," an A.D. second century bronze sculpture of an entire horse supported on the hoof of one leg. found in the grave of a Han general. A famous gilded bronze horse is another treasure. It is thought to have been given as gift from Emperor Wu to his sister. Horses were valued for practical and spiritual reason. They carried the Han to Central Asia and were believed to carry the emperor to heaven.

Han-era tiger

Art from India and Central Asia made its way into China in great amounts between the 1st and 5th centuries. During this period Buddhist art was created on the cave walls of Yungang and many Buddhist scriptures were translated into Chinese. Great works were created by the painter Gu Kazhi and the calligrapher Wang Xizhi and the poet Tao Yuanmung,

Many great works of pottery and ceramic art came from the Han Dynasty. Lovely vessels and objects were buried with dead and have been excavated by archeologists and looters. The first use of glazes on Chinese pottery dates back to this period. Han emperors and noblemen commonly decorated their tombs with pottery replicas of warriors, concubines, servants, horses, domestic animals, trees, plants, furniture, models of towers, granaries, mortars and pestles, stoves and toilets, and almost everything found in the real world so the deceased would have everything he needed in the next world.

Pictorial art during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) took the from of stone engraving, wall painting, and paintings on silk. Paintings mentioned in the Han period texts include Picture of Riding the Dragon to Ascend the Clouds, Picture of the Eastern Wall and Picture of the Western Wall, and Scripture of Grand Harmony. None of these remain today and we have no clue what they looked like. Han art is thought to had a solemn style and didactic function..The main objective of painting during this period was to educate people.

See Separate Article HAN DYNASTY ART: BRONZE MIRRORS, JADE SUITS AND TOMB FIGURES factsanddetails.com

Jade Suits and Pieces from Han Dynasties

During the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), the imperial family held jade in great esteem. While alive they wore jade pendants and ingested jade powder. When they died were covered and stuffed with jade. Banners and tomb tiles were imprinted the round pi disk, which was believed to assist the deceased reach the next world quicker.

In the Han period, jade objects were believed to possess auspicious meaning, their uses and functions multiplied. Circular jades---often containing images of twin-bodied animals, mask patterns, grain seeds, rush mat designs, curling chih dragons, and round tipped nipples---decorate buildings. Engraved dragon and phoenix patterns were popular in the Han imperial court.

The greatest expressions of the quest for immortality were the jade suits that appeared around the 2nd century B.C. About 40 of these jade suits have been unearthed. The jade suit of the 2nd century B.C. Prince Liu Sheng unearthed near Chengdu, Sichuan province was made of 2,498 jade plates sewn together with silk and gold wire. Liu Shen was buried with his consort who was equally well clad in a jade suit. Sufficient room was made for the prince's pot belly.

Jade suits were believed to slow decomposition and effectively preserve the body after death. A jade suit unearth in Jiangxi Province was made of roughly 4,000 translucent pieces of jade held together with gold wire. Designed to form fit and cover the body, it has the shape of a robot from 1950s B science fiction movie.

Art During the Tang Dynasty

Ideas and art flowed into China on the Silk Road along with commercial goods during the Tang period. Art produced in China at this time reveals influences from Persia, India, Mongolia, Europe, Central Asia and the Middle East. Tang sculptures combined the sensuality of Indian and Persian art and the strength of the Tang empire itself. Art critic Julie Salamon wrote in the New York Times, that artists in the Tang dynasty “absorbed influences from all over the world, synthesized them and a created a new multiethnic Chinese culture.”

Tang funerary vessels often contained figures of merchants. warriors, grooms, musicians and dancers. There are some works that have Hellenistic influences that came via Bactria in Afghanistan and Central Asia. Some Buddhas of immense size were produced.

None of the tombs of the Tang emperors have been opened but some tombs of the royal family members have excavated, Most of them were thoroughly looted. The most important finds are murals and paintings in lacquer. They contain delightful images of court life.

Proto-porcelain evolved during the Tang dynasty. It was made by mixing clay with quartz and the mineral feldspar to make a hard, smooth-surfaced vessel. Feldspar was mixed with small amounts of iron to produce an olive-green glaze.

See Separate Articles TANG DYNASTY ART: PAINTING, CALLIGRAPHY AND BUDDHIST CAVE ART factsanddetails.com TANG HORSES AND TANG ERA SCULPTURE AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com

Tang Horses

Tang horses are among the most famous works of Chinese art. Made from ceramic, some are glazed in blue, green amber and have elaborate saddle blankets and tasseled bridles. Other are made of unglazed ceramic and thereby look more modern like a Rodin statute. The horses are often in frantic positions: with their heads raises and nostrils flared, or twisting around to get at something on their backs. Many had a grooved channel running the length of the arched neck, where a real horsehair mane was placed, and had a hole in their rear for a horsehair tail. Most are only around 15 inches tall.

Tang horses are among the most famous works of Chinese art. Made from ceramic, some are glazed in blue, green amber and have elaborate saddle blankets and tasseled bridles. Other are made of unglazed ceramic and thereby look more modern like a Rodin statute. The horses are often in frantic positions: with their heads raises and nostrils flared, or twisting around to get at something on their backs. Many had a grooved channel running the length of the arched neck, where a real horsehair mane was placed, and had a hole in their rear for a horsehair tail. Most are only around 15 inches tall.

Chinese art specialist J.J. Lally told the New York Times, "Tang horses are the most widely popular image of Chinese art because they are immediately accessible to everyone. You don't have to read the Tang dynasty was a moment in Chinese art when there was a strong move toward realism and strong decorative impulse. Horses imported from the Near East were precious. In Tang China, the horse was the emblem of wealth and power. They are meant to embody rank and speed."

The Chinese used horses as far back as the Shang dynasty (1600 to 1100 B.C.) but these were mainly strong, draft animals. Later they began importing horses from Central Asia and Middle East. By the Tang dynasty horses were favorite subjects of not only artists but also poets and composers. The inspiration for the many of Tang horses were Tall horses, the heavenly horses from Central Asia introduced to China in the first century B.C.

Tang Dynasty Painting

During the Tang Dynasty ( both figure painting and landscape painting reached great heights of maturity and beauty. Forms were carefully drawn and rich colors applied in painting that were later called "gold and blue-green landscapes." This style was supplanted by the technique of applying washes of monochrome ink that captured images in abbreviated, suggestive forms.

During the late Tang dynasty (907-960) bird, flower and animal painting were especially valued. There were two major schools of this style of painting: 1) rich and opulent and 2) "untrammeled mode of natural wilderness." Unfortunately, few works from the Tang period remain.

Lovely murals were discovered in the tomb of Princess Yongtain, the granddaughter of Empress Wu Zetiab (624?-705) on the outskirts of Xian. One shows a lady-in-waiting holding a nyoi stick while another lady holds glassware. It is similar to tomb art found in Japan. A painting on silk cloth dated to the A.D. mid-8th century found in the tomb of a rich family in the Astana tombs near Urumqi in western China depicts a noblewoman with rouge cheeks deep in concentration as she plays go.

Famous Tang dynasty paintings include Zhou Fang’s Palace Ladies Wearing Flowered Headdresses, a study of several beautiful, plump women having their hair done; Wei Xian’s The Harmonious Family Life of an Eminent Recluse, a Five Dynasties portrait of a father teaching his son in a pavilion surrounded by jagged mountains; and Han Huang’s Five Oxen, an amusing depiction of a five fat oxen. Wang Wei (701-761) is a legendary Tang dynasty painter and poet who said "there are paintings his poems and poems in his paintings."

Dong Yuan is a legendary 10th-century Chinese painter and a scholar in the court of the Southern Tang Dynasty. He created one of the "foundational styles of Chinese landscape painting." The Riverbank, a 10th-century silk scroll he painted, is perhaps the rarest and most important of early Chinese landscape painting. Over seven feet long, The Riverbank is an arrangement of soft contoured mountains, and water rendered in light colors with ink and brushrstokes resembling rope fibers. In addition to establishing a major from of landscape painting, the work also influence calligraphy in the 13th and 14th century.

Maxwell Heran, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art told the New York Times: "Art-historically, Dong Yuang is like Giotto or Leonardo: there at the start of painting, except the equivalent moment in China was 300 years before.” In 1997, The Riverbank" and 11 other major Chinese painting were given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York by C.C. Wang, a 90-year-old painter who escaped from Communist China in the 1950s with painting which he hoped he could trade for his son.

Art During the Song Dynasty

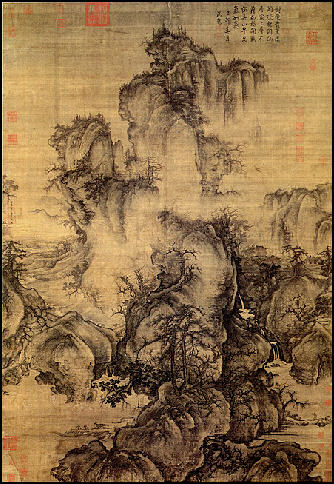

Early Spring by Guo Xi

The Songs ruled an empire rich in silk, jade and porcelain. They sent trading ships to India and Java and presided over a period of growth in trade and an expansion of the Chinese empire. Trade increased in the Indian Ocean partly as a response to the threat from Islamic intrusions into the area. Even so trade was not a respectable vocation and the emperor seized the property of merchants to create government monopolies.

During the Song dynasty Taoism and Taoist art were lavishly supported by the emperors Chen-tsung (998-1022) and Hui-tsung (1101-1125). The zenith of Taoist painting occurred in the 11th century, when 100 artists, chosen from 3,000 candidates, lead by chief painter Wu Tsung-yuan, were commissioned to paint the wall mural Immortal Protectors of the Dynasty in the Three Purities temple at Lonyang. The Northern Song dynasty poets Su Xun and his sons Su Shi and Su Zhe are highly regarded .

Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “ The tenth and eleventh centuries witnessed the flowering of one of the supreme artistic expressions of Chinese civilization: monumental landscape painting. During the period of social and political chaos that accompanied the fall of the Tang dynasty in 906, scholars retreated to the mountains, living in hermitages or in Buddhist temples. In nature they discovered the moral order they had found lacking in the human world. For Northern Song (960–1127) artists, the great mountain, towering above lesser mountains, trees, and men, was like "a ruler among his subjects, a master among servants". Continuing to uphold reclusion as a pure way of life, the Song landscapists painted "the heart of forests and streams" as a release from worldly concerns (1981.276). [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“The momentous shift during the early Song—from a society ruled by a hereditary aristocratic order to a society governed by a central bureaucracy of scholar-officials—also had a major impact on the arts. Song scholar-officials quickly laid claim to calligraphy and poetry as expressive vehicles uniquely suited to their class and sought to revive the natural and spontaneous qualities of earlier centuries. They also applied their new critical standards to painting. Rejecting the official view that art must serve the state, these amateur scholar-artists pursued painting and calligraphy for their own amusement as a form of personal expression.” \^/

Landscape painting matured during the Song Dynasty. Artists created paintings that viewers could gaze on, wander and travel through and dwell in. Artists who painted birds, flowers and animals tried not only to accurately depict the shape and appearance of their subjects, they also aimed to capture their internal emotions, ideas and essential characteristics.

Some scholars say that Chinese painting reached its pinnacle during the Song dynasty under Hui Tsung (1100-1126), an emperor who was much better painter than ruler. He set up and taught at China's first academy of painting and amassed a collection of 6,400 painting by 231 masters. Chinese artists often collected the works of other artists as sources of inspiration. The artists of many of the great masterpieces of Chinese are unknown. Among the great Song era painters who are known are Zhang Zeduan, Gu Hongzhong, Fan Kuan and Guo Xi. Guo Xi was a famous landscape painter. He once wrote: "wonderfully lofty are these heavenly mountains, inexhaustible in their mystery. In order to grasp their creations, one must love them utterly and never cease wandering among them, storing impressions one by one in the heart."

See Separate Articles SONG DYNASTY ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY LANDSCAPE, ANIMAL, RELIGIOUS AND FIGURE PAINTING factsanddetails.com SONG DYNASTY CERAMICS — PORCELAIN, JU WARE AND CELADON — AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Song Dynasty Porcelain

Some of the most beautiful porcelain ever produced was made during the Song dynasty (960-1279), when world-famous monochrome porcelains, including celedon, were produced. Celadon is green porcelain made with a slip and glaze, sometimes with incised and inlaid decorations. It is associated with both China and Korea.

Some of the most beautiful porcelain ever produced was made during the Song dynasty (960-1279), when world-famous monochrome porcelains, including celedon, were produced. Celadon is green porcelain made with a slip and glaze, sometimes with incised and inlaid decorations. It is associated with both China and Korea.

Wonderful crazed or cracked glazed pottery, produced by the shrinking and cracking of the glazes due to rapid cooling, appeared during the Song period. The earliest pieces with this kind of glazing were probably made by accident in the firing process but later was developed into an art form that had a great impact outside of China, influencing the famous tea ceremony ceramics of Japan.

Ching-te Chen in the Chiang-shsi province (present-day Jiangdezhen in Jiangxi Province) became the seat of imperial ceramic making under Emperor Chen Tsung around A.D. 1000. Porcelain from the imperial plant here was regarded as the best and was reserved for imperial use.

Ju ware, a kind of celadon from the Northern Song dynasty that ranges in color from blue to green, is the rarest of all forms of porcelain. Only 65 pieces of it exist and 23 of them are possessed by the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

Art During the Yuan Dynasty

During the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) painters worked at capturing their own feelings and ideas and the qualities of their ink and brush rather than qualities of their subjects. Scholar artists were the leading figures in the arts, and their painting were characterized by simplicity, understatement and transcendent elegance.

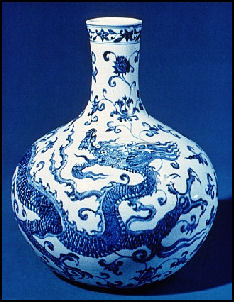

In the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) floral motifs and cobalt blue paintings were made under a porcelain glaze. This was considered the last great advancement of Chinese ceramics. The cobalt used to make designs on white porcelain was introduced by Muslim traders in the 15th century.

The blue-and-white and polychrome wares from the Yuan Dynasty were not as delicate as the porcelain produced in the Song dynasty. Multi-colored porcelain with floral designs was produced in the Yuan dynasty and perfected in the Qing dynasty, when new colors and designs were introduced.

The world record price paid for an art work from any Asian culture is $27.8 million, paid in March 2005 for a 14th century Chinese porcelain vessel with blue designs painted on a white background. The vessel contains scenes of historical events in the 6th century B.C. and has unique Persian-influenced shape. Only seven jars of this shape exist in the world. The buyer was Giuseppe Eskenazi., the renowned dealer of Chinese art, acting on behalf of a client. The previous record for porcelain was $5.83 million paid for a14th-century blue-and-white porcelain vessel called the pilgrims vessel in September 2003.

See Separate Articles YUAN ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; YUAN DYNASTY CRAFTS AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com

Art During the Ming Dynasty

During the Ming Dynasty scholarly painting continued to prevail and ink wash painting of the Imperial Painting Academy and Southern Song court was briefly popular. Paintings were often filled with human figures, whose size was an indication of their rank. During the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties two approaches to scholarly painting were developed: the first in which artists copied and studied ancient themes and subjects, and the second in which artists abandoned models and expressed their own creativity through inventive means. The individualist expressive form predominated in the mid Qing dynasty. Research on ancient inscriptions influenced painting in the late Qing period. Hanging scroll portraits of emperors and other nobleman contained Tibetan and Islamic influences.

During the Ming Dynasty scholarly painting continued to prevail and ink wash painting of the Imperial Painting Academy and Southern Song court was briefly popular. Paintings were often filled with human figures, whose size was an indication of their rank. During the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties two approaches to scholarly painting were developed: the first in which artists copied and studied ancient themes and subjects, and the second in which artists abandoned models and expressed their own creativity through inventive means. The individualist expressive form predominated in the mid Qing dynasty. Research on ancient inscriptions influenced painting in the late Qing period. Hanging scroll portraits of emperors and other nobleman contained Tibetan and Islamic influences.

Ming Dynasty ceramics were known for the boldness of their form and decoration and the varieties of design. Craftsmen made both huge and highly decorated vessels and small, delicate, white ones. Many of the wonderful decorations and glazes---peach bloom, moonlight blue, cracked ice, and ox blood glazes; and rice grain, rose pink and black decorations---were inspired by nature.

In 1402, the Ming Emperor Jianwen ordered the establishment of an imperial porcelain factory in Jingdezhen. It's sole function was to produce porcelain for court use in state and religious ceremonies and for tableware and gifts.

Between 1350 and 1750 Jiangdezhen was the production center for nearly all of the world's porcelain. Jiangdezhen was located near abundant supplies of kaolin, the clay used in porcelain making, and fuel needed to fire up kilns. It also had access to China's coast, which was used for transporting finished products to places in China and around the world. So much porcelain was made that Jingdezhen now sits on a foundation of shards from discarded pottery that over is four meters deep in places.

See Separate Articles MING DYNASTY ART factsanddetails.com ; MING DYNASTY PAINTING AND ITS FOUR GREAT MASTERS factsanddetails.com ; MING DYNASTY PORCELAIN factsanddetails.com

Art During the Qing Dynasty

Art produced during the Qing period was particularly ornate. Incorporating Tibetan, Middle Eastern, Indian and European influences, it included elaborately carved wood, baroque ceramics, heavily embroidered garments, and intricately worked gold and rhinoceros horn. Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times: “What the Qing wanted in court art was more: more ingenuity, more virtuosity, more bells and whistles, extra everything. When it came to scale, they went for extremes, the teensy and the colossal, cups the size of thimbles, jades the size of boulders. The Confucian middle way was not their way.” Among the more extravagant pieces of Qing art are silk costumes made with applique embroidery; a royal hat made of sable, silk floss, gold, pearls and feathers; and a five-foot-high cloisonne elephant with a lamp on its back.

Large wall-size portraits of ancestors were produced for the aristocracy and ruling class during the Qing dynasty. They feature realistic seated renderings of individual painted in bright colors. They were often placed over family altars. The paintings were regarded as mediums for communications to deceased relatives. The Chinese have traditionally believed the dead didn't die they just went to a different world where they could be contacted by the living. The dead were believed to want to hear news and receive offerings and sacrifices from time to time by living relatives.

Large wall-size portraits of ancestors were produced for the aristocracy and ruling class during the Qing dynasty. They feature realistic seated renderings of individual painted in bright colors. They were often placed over family altars. The paintings were regarded as mediums for communications to deceased relatives. The Chinese have traditionally believed the dead didn't die they just went to a different world where they could be contacted by the living. The dead were believed to want to hear news and receive offerings and sacrifices from time to time by living relatives.

The Shanghai School was an influential painting movement founded in the mid-19th century that is credited with combining traditional Chinese ink paintings with modernist trends. Incorporating heavy black strokes to outline figure and bring attention to details, it influenced Japanese wood block printing and early manga art among other things. Important Shanghai School artists included Qin Zuyong (1825-1884) and Qian Huian (1833-1911). Describing a work called Kingyo-zu by the artist named Xugu Christoph Mark wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Light touches diluted ink to create reflections on water as abstract goldfish swim beneath...The scant use of color---a reddish orange for the fish---is characteristic of...paintings that rely heavily on inking skills to convey what color would be used for in other styles."

Qing dynasty porcelain was famous for its polychrome decorations, delicately painted landscapes, and bird and flower and multicolored enamel designs. Many of the subjects had symbolic meanings. The work of craftsmen reached a high point during the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722). During a rebellion in 1853, the imperial factory was burned. Rebels sacked the town and killed some potters. The factory was rebuilt in 1864 but never regained its former stature. With the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912, the long history of Chinese porcelain making drew to a close.

See Separate Article QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com ; CULTURE AND ART UNDER THE QIANLONG EMPEROR (ruled 1736–95) factsanddetails.com

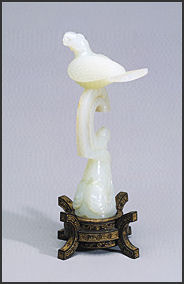

Jade Pieces from the Qing Dynasties

Jade pieces from the Qing imperial court were characterized by their impressive size, neatness and symmetry. Common motifs included dragons, emblems of the emperor, various auspicious symbols, and imperial inscriptions and marks. These jade pieces were often put on sandalwood pedestals or kept in special cases and boxes.

During the early Qing Dynasty, jade from Xianjiang was carved into elaborate floral designs, shallow reliefs the thickness of paper and ornaments inlaid with colored glass or gold and silver thread.

Jadeite carving really took off under the Qianlong Emperor, who preferred the varied translucent colors of jadeite to the opaque "chicken bone" jade and "mutton-fat" nephrite that was prized before him. Jadeite from the Yunnan Province and northern Burma were imported into China in large quantities in the 19th century and became prized above all other kinds of jade.

Qianlong Emperor and the Arts

The Qianglong Emperor loved the arts and presided over a period when the arts flourished. He painted and did calligraphy, collected jades, porcelain and bronzes, played a zitherlike instrument called the qin and wrote 44,000 poems and thousands of essays. In between that he found time to make 150 lengthy public relations tours of China and sign off on every edict issued by his government.

The Qianlong Emperor ordered scholars to organize, collect and categorize paintings, calligraphy, and books. He commissioned porcelain vessels decorated with his poems surrounded by flowers. His art collection contained hundreds of thousands of paintings. sculptures and object of art, many of which have his commentary and poems scribbled on them. His tastes leaned towards the understated. He loathed ostentatious skill

The Qianlong Emperor collected 1,000 dramas and novels from around the country and sponsored projects to catalogue and copy all surviving Chinese writing, a task that took 300 scholars and 3,600 scribes 10 year to complete and contained 4.2 million pages. But at the same time he destroyed almost as many books as he saved by banning and ordering the burning of books deemed anti-imperialist or morally or politically unfit.

The largest Qing tomb belongs to the Qianlong Emperor. The tomb covers half a square kilometer and contains beamless stone chambers adorned with bodhisattvas and Tibetan and Sanskrit sutras. Construction started when he was he 30 (he died when he was 88) and 90 tons of silver was spent on it.

Image Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei; University of Washington

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021