SHANG DYNASTY BRONZE TECHNOLOGY

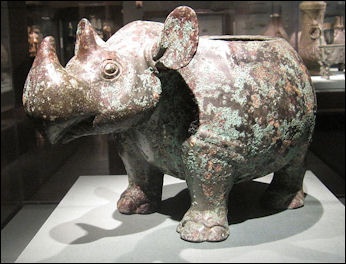

Rhino-shaped bronze zun

Bronze technology, the chariot and writing were probably developed with foreign influences by the Shang, but were given distinctly Chinese elements. The Shang rulers monopolized the use of bronze tools and weapons while their farmer subjects used only implements made from stone.

By around 1200 B.C. artisans were able to cast large bronze pieces, technology that wasn’t achieved in the Mediterranean for another thousand years. The Shang added lead to the mixture of tin and copper and developed a sophisticated casting process that allowed them to cast bigger and bigger bronze objects. The largest Shang vessel ever discovered weighed 1,900 pounds. According the Oxford University scholar Jessica Rawson, "the diversity of decorative motives on the bronzes indicated that influence of or manufacture by neighboring, contemporary societies of some sophistication."

Most bronze objects from the Shang Dynasty are vessels used in various kinds of rituals. Three-legged bronze vessels from the 12th century B.C. contain images of bears, wolves and tigers. Other interesting bronze art from the Shang Dynasty includes bronze masks that look like bizarre Halloween masks and may have been used by shamans; and a slender nine-foot-high-tall figure with stylized shamanist-style head and enormous hands that once held an elephant tusk. Soldiers from this period wore bronze chest plates engraved with attacking leopards with huge claws, birds with wolf ears and eagle beaks, hawks grabbing bear cubs, tigers leaping on antelopes, and dragons

During the Shang dynasty and Zhou dynasties jade objects were important objects in ceremonies and rituals. Shang Dynasty circular jades were generally similar to northwestern circular jades. Late Shang pieces featured raised inner rims and thin outer edges, sets of carved concentric circles and images of curling dragons, fish, tigers and birds. The Shang also made monster-face amulets with turquoise-inlay mosaics of swirls and eyes and part-tiger-part-human marble monsters.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: PREHISTORIC AND SHANG-ERA CHINA factsanddetails.com; XIA DYNASTY (2200-1700 B.C.): CHINA’S FIRST EMPERORS, THE GREAT FLOOD AND EVIDENCE OF THEIR EXISTENCE factsanddetails.com; ERLITOU CULTURE (1900–1350 B.C.): CAPITAL OF THE XIA DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; SHANG DYNASTY (1600 – 1046 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; SHANG ORACLE BONES factsanddetails.com; ORACLE BONE INSCRIPTIONS factsanddetails.com; SHANG RELIGION AND BURIAL CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com; SHANG DYNASTY LIFE AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com; SHANG SOCIETY factsanddetails.com; SHANG KINGS AND GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Shang Ritual Bronzes in the Arthur M. Sackler Collection” by Robert Bagley Amazon.com; “Chinese Bronzes” by Christian Deydier Amazon.com; “Chinese Bronze Ware” by Li Song Amazon.com; Ancient Chinese Jade Collection: Chinese Edition. Compilation Edition (V1+V2) by Henry Liaw and C.F. Zhou Amazon.com ; “Jades from China” by Angus Forsyth Amazon.com; “Jade: A Study in Chinese Archaeology & Religion” by Berthold Laufer Amazon.com “Jade of the Shang Dynasty” by Kako Crisci | Amazon.com; “The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China(ca. 1200-1045 B.C.)” by David N. Keightley Amazon.com, an excellent source on Shang history, society and culture; “Daily Life in Shang Dynasty China” by Lori Hile Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art)by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Shang Bronze Music

Zhou-era bronze bell

J. Kenneth Moore of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In the period between 3,500 and 2,000 years ago, Chinese rulers constructed elaborate tombs containing weapons, vessels, and remains of servants and, in some cases, full ensembles of musical instruments such as stone chimes (known today as qing), ovoid clay ocarinas (xun, 2005.14), and drums. In addition to these instruments, Shang-dynasty finds (ca. 1600–ca. 1066 B.C.) include beautifully decorated dual-toned bronze bells with and without clappers (ling and nao, 49.136.10), barrel-shaped drums (gu), and bronze drums. Hints as to the use of these instruments were inscribed on small pieces of bone (oracle bones) dating from the fourteenth to the twelfth century B.C. These pictographs make reference to ritual dance and music and those depicting instruments are easily equated with modern Chinese characters. [Source: J. Kenneth Moore Department of Musical Instruments, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org]

“From the earliest historical periods, particularly in ritual music from the Bronze Age onward, bells have been an essential component of instrumental ensembles in China The earliest known bronze bells, from the Shang dynasty (ca. 1600–1050 B.C.), are the type called nao (49.136.10), in which the mouth of the bell faces up, and seem to have been played singly or in sets of three or five. After the tenth century, during the Zhou dynasty (ca. 1046–256 B.C.), sets of bells of the zhong type, suspended from a wood frame, were used. [Source: J. Kenneth Moore Department of Musical Instruments, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Both the zhong and the nao are struck externally and, thanks to their unique construction, are capable of producing two accurately tuned tones of intervals sounding a major or minor third. Both types are expertly cast, with sides that flare from the crown to the mouth, which is elliptical in cross section and concave in profile. Such a shape, used for small animal bells since 1500 B.C., provides one tone when struck in the center and another when struck on the side. The earliest evidence of a chromatic scale is a set of ten nao from the tenth or eleventh century B.C., unearthed in 1993 in Ningxiang, Hunan Province. The handlelike stem projecting from the crown helps to secure the bell to a frame. Tuned bells ranged greatly in size; some were only about nine inches tall, while the largest found to date is about forty inches tall and weighs 488 pounds."^/

Images of Chinese dancers have been found on 4,500-year-old pottery. The earliest forms of dance grew out of religious rituals — including exorcism dances performed by shaman and drunken masked dances — and courtship festivals and developed into a forms of entertainment patronized by the court. In ancient texts there are descriptions of troupes of women dancers entertaining guests at official banquets and drinking parties. Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen wrote: “It is known that during the Shang dynasty (c. 1766–1066 BC) hunting dances as well as dances imitating animals were performed...The dances imitating animals and employing the so-called “animal movements” have been common in most cultures. In fact, animal movements still form an integral part of many martial art, dance and theater traditions today.” According to Chinese mythology the cultural hero Fu Xo gave humans the fish net and the Harpoon Dance; the god She Nong created agriculture and the Plough Dance; and the Yellow Emperor, the legendary ruler from the 26th century B.C., is honored with Dance of the Cloud Gate. Ancient texts also mention hunting dances and a Constellation Dance, which was performed to seek help from the gods for a good harvest. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki ]

Shang Dynasty: China’s First Real Bronze Age Culture

bronze bird

The oldest example of bronze yet discovered in China is a 5,000-year-old bronze knife found at a Yellow-River-based Yangshao culture site. Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “In addition to pottery, amidst the array of wooden, stone, and bone implements found at Yangshao sites is the earliest bronze implement yet found in China. It is a knife, dating to about 3000 B.C. Unless and until an earlier example appears elsewhere,Yangshao culture must be seen as the source of China’s transition into the Bronze Age.” Its seems possible or likely that this this knife was obtained through trade rather than manufactured locally. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu ]

Significant bronze metallurgy in China dates back to 2000 B.C., significantly later than southeastern Europe, the Middle East and Southeast Asia, where it developed around 3600 B.C. to 3000 B.C. The oldest bronze vessels date back to the Hsia (Xia) dynasty (2200 to 1766 B.C.).

Despite all this the Shang Dynasty is regarded as China’s first real Bronze Age culture Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “It was the Shang people who located deposits of copper and tin and learned the art of forging bronze. The Shang is the beginning of the Bronze Age in China. Prior to that time, tools were fashioned from wood and stone. It is customary in speaking about pre-Bronze Age China to distinguish between the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) and Neolithic (New Stone Age) periods, a division employed in prehistoric studies worldwide. In China, the Neolithic period, which is the period in which the age of stone tools overlaps the age of agriculture, begins about 7000 B.C. /+/

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “The development of metal-working technology represents a significant transition in Chinese history. The first known bronze vessels were found at Erlitou near the middle reaches of the Yellow River in northern central China. Most archaeologists now identify this site with the Xia dynasty (c. 2100-1600 B.C.) mentioned in ancient texts as the first of the three ancient dynasties (Xia, Shang, and Zhou). It was during the Shang (1600-1050 B.C.), however, that bronze-casting was perfected. Bronze was used for weapons, chariots, horse trappings, and above all for the ritual vessels with which the ruler would perform sacrifices to the ancestors. The high level of workmanship seen in the bronzes in Shang tombs suggests a stratified and highly organized society, with powerful rulers who were able to mobilize the human and material resources to mine, transport, and refine the ores, to manufacture and tool the clay models, cores, and molds used in the casting process, and to run the foundries...Altogether the bronzes found in Fu Hao's tomb weighed 1.6 metric tons, a sign of the enormous wealth of the royal family. These vessels were not only valuable by virtue of their material, a strong alloy of copper, tin, and lead, but also because of the difficult process of creating them. The piece-mold technique, used exclusively in China, required a great deal of time and skill.[Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

See Separate Article BRONZE ART IN ANCIENT CHINA: RITUAL VESSELS AND HOW THEY WERE CAST factsanddetails.com

High Level of Achievement of Shang Bronzes

animal mask on a hu

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “No other Bronze Age culture ever achieved a level of aesthetic perfection in bronze comparable to Shang culture. The imaginative vision and technical expertise that are combined in Shang ritual vessels represent a peak of virtuoso art that is rare in world history. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“It should be understood that to achieve such a level of magnificence, the Shang had to invest enormous resources. Copper and tin, the principal components of Shang bronzes, were not easy to come by. Although there are substantial deposits of these minerals within a few hundred kilometers of Xiaotun, given the rudimentary forms of mining and transportation available, quarrying and shipping the ore to the capital would have been a great drain on labor and a major expense to the Shang elite. /+/

“Nor were these ores invested in productive industry. The Shang could have used copper or bronze to strengthen their ploughs, but they did not; they could have used them to reinforce their weaponry, but with few exceptions they did not. Bronze was reserved for the near-exclusive use of the ritual industries, and within that, chiefly for the manufacture of sacrificial vessels. It was the ancestors who enjoyed the fruits of the most developed form of manufacturing technology in Shang China. /+/

“Moreover, unlike Mediterranean and Central Asian Bronze Age cultures, the Shang employed bronze in a most resource-intensive way. Elsewhere, bronze objects were generally wrought – that is, thin sheets of bronze were hammered or otherwise shaped to form objects that were relatively light in weight, minimizing the amount of bronze necessary. The Shang, by contrast, cast bronze in molds, pouring large quantities to create thick-walled solid bronze objects. The largest are so heavy that they cannot even be lifted by a single person. Shang ancestors had no reason to complain that their descendants were stingy!” /+/

Development of Bronze Technology in the Shang Period

bronze ritual wine server

Dr. Eno wrote: “A number of Shang cultural sites considerably earlier than the capital at Xiaotun have been excavated. Some are the ruins of substantial cities, and many scholars believe that they include the site of at least one earlier Shang capital – some scholars believe that one of the larger sites was a Xia Dynasty city, though others still do not accept the historicity of the Xia. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University/+/ ]

“The sites of Shang culture that pre-date the capital of Yin, to which the Shang moved about 1300 B.C., have yielded a wide range of early bronzes. When we view these together with those excavated from the royal tombs at Yin – and the thousands that were taken from those graves over the centuries by grave-robbers and sold to private collectors and museums around the world – we can reconstruct a systematic portrait of the evolution of this emblematic art of the Shang.” /+/

“The bronzes were crafted both for use and for display. The Shang people had inherited a highly developed craft of pottery from their neolithic ancestors, a craft that had drawn ideas from many of the distinct agricultural societies that had flourished in China and joined the complex ethnic mix of the Shang. Potters did much more than produce pots, pans, dishes, and cups. A rich repertoire of conventional forms had evolved: tripods for boiling, covered steamers, bowls for hot grains, platters for meat and fish, kettles for hot drink, pitchers and jugs for wine, goblets, beakers, basins – each type with its own conventional variety of ever-evolving forms. The bronzes were based upon these pottery forms, and one of their great aesthetic virtues is the way that they combine the angular potential of cast metal with the plastic suppleness of earthenware. /+/

By around 1200 B.C. artisans were able to cast large bronze pieces, technology that wasn’t achieved in the Mediterranean for another thousand years. The Shang added lead to the mixture of tin and copper and developed a sophisticated casting process that allowed them to cast bigger and bigger bronze objects. The largest Shang vessel ever discovered weighed 1,900 pounds. According the Oxford University scholar Jessica Rawson, "the diversity of decorative motives on the bronzes indicated that influence of or manufacture by neighboring, contemporary societies of some sophistication."

Eno wrote: “The sight of these shining masterworks arrayed in rows upon the altars of the dead would have been a sight to marvel at. Perhaps it was the unparalleled artistry of the bronzes which not only made them sacred to the Shang but which led them to ignore more utilitarian potentials of their new metal craft.” /+/

Manufacturing Bronze Objects in the Shang Dynasty

Dr. Eno wrote: “The way that bronzes were cast in Shang China suggests that it was the potters who first developed the arts of bronze technology. Bronze vessels were cast in clay molds. These molds were, in turn, shaped by clay models. The first step was for the bronze caster to design a model of the eventual bronze vessel in clay. He would shape the clay to the vessel form desired and then, using fine tools, he would inscribe the figure with designs of great complexity. The incision of the model was the great departure from pottery traditions, for pottery was rarely incised, it was generally pressed with patterns or painted. As the art progressed, the forms, as well as the designs, became increasingly elaborate and independent of forms associated with pottery. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“Once the clay model was complete and had hardened, the caster would press wet clay around the model until he had shaped it fully and pressed it to absorb all the delicately incised designs. Then, before it was dry, he would cut it off in sections, usually three. This would become the outer mold for the bronze. He would then create a solid core which would rest on small bronze studs laid upon the base of the reassembled mold. This core would create the space of the interior of the vessel – its “useful emptiness,” as Laozi might put it. Sometimes this core was also inscribed, usually with the name of the ancestor to whom the vessel was to be dedicated and perhaps with an elaborate clan mark which would signify its origins. Occasionally, towards the end of the Shang, a longer inscription might be written to record the occasion on which the bronze was cast, but such inscriptions are rare in the Shang (they become very common during the Western Zhou). /+/

“Finally, molten bronze would be poured into the fully assembled mold. The bronze studs which supported the core over the base of the vessel would be melted into the vessel’s base. Once the bronze had cooled, the clay mold was shattered, freeing the vessel, which was then polished. Any defects were carefully corrected, yielding the sharply detailed designs still visible after 3 millennia. Although the vessels we see today have all developed the rich green patina of oxidized bronze, the newly cast vessels would have gleamed like gold.” /+/

In other cultures bronze vessels and figures were generally made using the lost wax casting technique, which worked as follows: 1) A form was made of wax molded around a piece of clay. 2) The form was enclosed in a clay mold with pins used to stabilize the form. 3) The mold was fired in a kiln. The mold hardened into a ceramic and the wax burned and melted leaving behind a cavity in the shape of the original form. 4) Metal was poured into the cavity of the mold. A metal sculpture was created and removed by breaking the clay when it was sufficiently cool.

Shang Era Bronze Factories

Yuan Guangkuo wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: “Foundries for bronze casting were found in the cities of Zhengzhou (rank 1) and Panlongcheng (rank 3). Two important bronze foundries were identified at Zhengzhou named Nanguanwai (located in the south, between the smaller, inner enclosure and the outer wall) and Zijingshan (in the north, outside the inner enclosure). At Nanguanwai, the main crafts were bronze vessels and tools. The workers at Zijingshan specialized in the production of bronze knives. [Source: “Discovery and Study of the Early Shang Culture” by Yuan Guangkuo, A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, Edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing, 2013 /thirdworld.nl ~|~]

“The clay molds, crucibles, and furnaces from these areas of Zhengzhou reveal that early Shang casting technology was quite developed. Bronze vessels were produced by piece-mold casting, which involved four main steps: shaping the clay model, production of the clay mold, casting, and finishing. In general more tin was used to produce the early Shang bronze vessels than those of the Erlitou period, but overall, the amount of tin still was relatively low. The early Shang bronze objects also contain varying amounts of lead (Zhu 2009 : 689–694). ~|~

“With respect to decorative techniques for the production of bronze vessels, an interesting development was the appearance of animal heads in high relief during the early Shang period. This made the decorations more three-dimensional. This type of decorative technique became dominant during the late Shang period, as seen on the bronze vessels at Yinxu. The most complex form of decoration on bronze vessels was found at the city of Xiaoshuangqiao. The earliest Shang bronze construction component found there has a unique shape and is heavily decorated. The “beast face” ("shoumianwen") pattern was applied on the front and on both sides, seemingly indicating a fighting scene between a dragon and tiger. This artifact reveals a high level of bronze-casting technology and artistic expression during the early Shang period (Henan Provincial 1993 : 76). ~|~

Shang Bronze Images and Vessel Types

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “By the time of the early Shang, bronze wine vessels and food containers began to appear in sets. They matured further in the late Shang. For example, sets of food containers ("ting", "yen", "li", "kuei ", and "tou"), wine vessels ("ku", "chüeh", "chi", "chia", "lei", "p'ou", "tsun", and "you"), and water containers ("yü" and "p'an") were commonly seen. These bronze wares were the most representative ritual objects in the system of rites. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei\=/ ]

Common motifs for Shang ritual bronze vessels were dragons, birds, bovine creatures, and a variety of geometric patterns. At the bottom of one yu basin is an arrangement of flower stems encircled by dragon heads with holes from which steam escaped from the vessel.

Dr. Eno wrote: “ The forms of the bronzes are outstanding artistic creations, but what particularly captures the imagination are the inscribed designs. The bronzes designs reflect a fantastic animal world, filled with dragons, monsters, regal birds, snakes, cicadas, and other animals, both real and fantastic. These animal images occupy space filled with intricate and pulsating patterns; the rarest surface of a Shang bronze is smooth, bare space – except for occasional punctuating regions of relative quiet, the fully evolved bronze conveys a sense of dynamic movement in every part. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

The Lei wine vessel with sheep heads, lozenge and knob pattern at the National Palace Museum, Tapei dates to the Late Shang Dynasty, c. 13th to 11th century B.C.. It is 37.3 centimeters high and 31.3 centimeters wide. The Square Zun wine vessel with round mouth, animal heads, and animal mask pattern dates to the same period. It is 44.9 centimeters tall and 43.5 centimeters wide.

Early and Middle Shang Bronze (16th-13th Century B.C.)

According to the Shanghai Museum:“ During the early and middle Shang dynasty, bronze casting evolved further. Rituals that mainly involved wine vessels became important, and bronze weapons increased in variety. The animal-mask motif decorated many bronzes, executed with bold, deeply-cut linear elements and becoming ever more complex. The mold-making process became sophisticated, and an ingenious technique was developed for casting a complicated shape in a sequence of separate pours of metal. Many bronzes dating from this time have been unearthed along the middle reaches of the Yellow and Yangtze rivers. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Li with animal mask

The pattern on a Hu (wine vessel) with an animal-mask design is similar to the lines on the pottery of the Longshan Culture (3000 –1900 B.C. ) and those on the jade deity's head of the Liangzhu Culture (3300–2300 B.C.), very likely to be a non-realistic. Pots of the same shape have been unearthed in the Central Plains region, usually with a loop handle. The two rings can be threaded with a rope, which has a similar function as a loop handle. Bronze vessels prior to the mid-Shang have not yet been found with specific inscriptions. But on the inside wall of the ring foot of this pot is cast with a character ‘X’, like a small cross, which should be the clan emblem. This is one of the earliest inscriptions on bronzes found so far.

A jia (wine vessel) with an animal-mask design was used for sacrificial rituals. From the traces of soot on the outer base and the white watermark in the belly, it can be deduced that it is also a vessel used to heat wine. Bronze Jia appeared in the late Xia (18th-17th century B.C.) and its shape matured by the mid-Shang . In the mid-Shang dynasty, they usually had a flat bottom, so a pouch-shaped like this was quite uncommon. The surface of the vessel is decorated with animal-mask motif with dense and exaggerated lines, showing a mysterious and dignified style. It is the only piece with such decoration among the existing bronze Jia of the mid-Shang dynasty.

The Gui (food vessel) gradually become a major artefact in the bronze sacrificial wares after its advent in the early Shang. By the mid-Western Zhou, the use of Gui was gradually institutionalized. The number of vessels used was clearly regulated according to the rank of the user, usually in even numbers matched with Ding. Bird-like patterns are often used to adorn the rims on the rectangular walls of the vessels of the late Shang and early Zhou, such as the belly part of square Ding and the stand of Gui. The inscription of the only word Jia found in the inner base is the name of the owner. This is an example of the Zhou people marking with Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches.

Late Shang and Early Western Zhou Bronze (13th-11th Century B.C.)

According to the Shanghai Museum:“ The late Shang and early Western Zhou dynasties witnessed the zenith of Chinese bronze casting. During this period the sets of bronzes used in ritual (originally mainly wine vessels) changed. Although at first the early Western Zhou people followed the Shang ritual system, they gradually developed ceremonies in which food containers played an important role. Using techniques that produced both high and low relief, artisans designed bronzes entirely covered with elegant patterns. They also further refined the mysterious animal-mask motif. Inscriptions first appeared on late Shang bronzes. The inscriptions on Western Zhou bronzes are often lengthy. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

The Gong Fu Yi Gong (wine vessel) is a splendid piece. At the front of the Gong lid is the head of an imaginary animal, with a pair of giraffe's horns, a pair of rabbit's ears and glaring eyes. Behind each horn, there is a small snake. On the central ridge of the lid, there is a small dragon carved in relief, with a long body and a curled tail. On the rear end of the cover is carved an ox head with protruding horns, pricked ears and corked tongue, corresponding to the ox head handle. A large-sized phoenix pattern decorates the belly part, in regal and solemn air. Other phoenixes are decorated on the ring foot, the back of the big phoenix and lids and other parts, in different shapes and picturesque disorder. The vessel is exquisitely cast and decorated, giving strong mystical overtones. Gong, a ritual wine vessel, comes in two forms. The whole vessel is either shaped like an animal, often an ox or ram, or the lid of the vessel is shaped as a mythical creature while the body is jug-shaped with a ring foot. This piece belongs to the second type. With no background pattern on the vessel, it was a new trend in the ornamentation of the bronzes of the late Shang dynasty.

Huang Gu (wine vessel) is a drinking vessel. This piece is exquisitely shaped and beautifully decorated, indicating extremely high casting technology and design level. The openwork carving at the ring foot is quite uncommon among Gu wares. The vessel is a treasure in bronze Gu of the Shang dynasty. It gains its name for the inscription in the foot ring Huang, the family name of the maker.

Ya Hu Square Lei (large wine vessel) is commonly seen in the late Shang and mid-Western Zhou dynasties. Bronze art saw its peak in the late Shang dynasty. This piece of work is imposing and dignified, exquisite and magnificent, standing out among all its kind. It is in six-layer high relief design from top to bottom against a background of fine and beautiful cloud and thunder pattern. The rim, the upper belly and the ring foot are decorated with bird-like designs, with symmetric dragon designs at the shoulders, a front beast head of big spiral horns in the middle, animal-mask motifs on the middle and lower parts of the belly and sharp clawed feet at the bottom. Some protruding parts like the horns and dragon tails are decorated with intaglio lines, showing a ferocious and mystical beauty. This is a typical ware of ‘three-section all-over pattern vessel’, representing the supreme level of bronze casting technology at its peak.

Zun (wine vessel) of Marquis Lu gets its name from the four lines of 22 characters engraved on the base of the inner belly which records King Zhou commanding Duke Ming to make the expedition to the East, and rewarding Marquis Lu. It is plain and unadorned as a whole with nodular shape on the surface and concave-convex alternation, looking simple and modest. It is distinctively shaped and unique of its kind. The bronze wares of the early Western Zhou inherited the animal-mask motif of the late Shang, with simpler decorations on some utensils. The Zun of Marquis Lu reflected this unique aesthetic appeal to the extreme and at the same time pioneered the simple style of the bronzes of the middle and late Western Zhou.

Pou (food vessel) with Four Ram Heads is very interesting. The mineralization of the whole vessel produced basic cupric carbonate, which made the surface of the ware shiny and green, beautiful and mysterious. The ram heads could be covered on the ornamentation on the shoulder, which implied that the heads were cast separately. The body of the vessel was case first, and then holes and passages were left on the shoulder and finally pottery model was built on the holes and passages to cast the ram heads. Such unique decorative composition is only found in early and middle Shang bronze wares, with an exception of the Yin Ruins, and the casting region remains a mystery to date.

Shang Taotie

Most Shang vessels were decorated with taotie, face-like symbols with “eyes” composed of swirling lines. These designs have been used by archeologists to determine the spread of Shang culture. According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The primary attribute of this frontal animal-like mask is a prominent pair of eyes, often protruding in high relief. Between the eyes is a nose, often with nostrils at the base. Taotie can also include jaws and fangs, horns, ears, and eyebrows. Many versions include a split animal-like body with legs and tail, each flank shown in profile on either side of the mask. While following a general form, the appearance and specific components of taotie masks varied by period and place of production.” [Source: Department of Asian Art, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York:The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. metmuseum.org\^/]

Dr. Eno wrote: “Although there is a great wealth of animal imagery, a single motif tends to dominate the bronze designs, by its frequency, its size, and its central placement. This is the image of a strange symmetrical monster mask, known by Classical times as a "taotie" image. The taotie, Classical texts tell us, was a beast of insatiable greed – both of the Chinese characters used to write its name are based on the graphic element of the verb “to eat.” The taotie image that we see on the bronzes, with its staring eyes and ever-gaping jaw, does suggest such a rapacious beast – but why is it there? Nothing we know would permit us to claim that the “taotie” beast Classical imagination drew on the same mythical or symbolic lore that the Shang designers had in mind. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The taotie generally occupies the central bands, or “registers,” of the bronze, and is centered so that its symmetrical form extends to the edge of each side of the vessel. If you look at the entire form, the face of the beast stares at you. But if you look at either side alone, you see instead a full figure of the beast in profile. This double figure of the taotie is more visible in some cases than in others, but generally constitutes a basic feature of the motif. /+/

Theories Behind Shang Taotie

taotie mask

Currently, the significance of the taotie, as well as the other decorative motifs, in Shang society is unknown. Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “There may be no issue of Shang culture that has created more controversy than the question of the significance of the eerie animal imagery of the bronzes. The bronzes have been known since antiquity, though not necessarily as artifacts of Shang culture, and traditionally it was widely assumed that these designs had some very direct symbolic function which was mysterious only because we lacked the interpretive key. During the middle part of the 20th century, however, an art historian named Max Loehr, working at the University of Michigan, proposed an entirely different approach. He suggested that it could be possible to see the taotie and other forms as developing solely from an artistic imperative, with no fixed symbolic meaning whatever. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Loehr was writing at a time when Xiaotun was the sole excavated Shang site. Although he was able to view the bronzes in private and museum collections throughout the world, as well as those from Xiaotun, there existed no variety of Shang sites that would allow him to compare the work of earlier casters with those of the later period at Yin. Undaunted by this lack of any chronological control mechanism, Loehr suggested that he could detect which among the known bronzes were early and which were late. The earliest, he said, were those which included a single thin band of decoration on which the sole discernable animated motif were pairs of staring eyes. These, Loehr claimed, were the artistic inspiration for the taotie. As the bronze caster’s artistic imagination evolved, Loehr believed, the band expanded and the eyes were elaborated into the full animal face. At this stage of the developmental process, the artists began to incorporate supplementary imagery into the vessels to complement the central motif. Finally, the latest vessels were engulfed in animal imagery, designs that frequently began to influence the shape of the vessel itself, not only the patterns inscribed on it. /+/

“Altogether, Loehr identified what he believed to be five distinct stages in the evolution of the bronze imagery. The force of his claim was to deny that the imagery on the bronzes possessed any religious significance. Aesthetics alone, Loehr held, could account for the development of the tradition. Loehr’s model gained enormous prestige decades later when other Shang sites were excavated. The results were precisely as Loehr had predicted. The earliest sites yielded exclusively bronzes consistent with Loehr’s “Period I” criteria; mid-Shang sites possessed bronzes of the first through the third of Loehr’s periods; late Shang sites possessed all five styles. Loehr’s model of the evolution of bronze decor was decisively confirmed. /+/

“Nevertheless, Loehr’s conclusions concerning religious versus aesthetic significance continues to be open to debate. In the 1980s K.C. Chang published an alluring set of essays that portrayed Shang religion very much in terms of shamanism, with the spirit world populated by the angular animals of the bronzes as well as by the ancestral spirits. Animals were, for Chang, the shaman’s vehicle: they were the intermediaries between the human and spiritual worlds in a way resonant with totemic societies elsewhere in the world. /+/

“Chang’s theory resonates very well with much of what we know about early Chinese religion, but it also leaps far beyond the evidence we currently possess. It can be called a “speculative” hypothesis, one not yet subject to a definitive test, much as Loehr’s theory was once considered speculative. Perhaps in the future, additional archaeological finds will allow us to pass as convincing a verdict on Chang’s ideas as we have been able to on some of Loehr’s. /+/

“Other theories concerning the origins and significance of the animal figures on the bronzes have been offered in great profusion. Two theories that bear some relationship to Loehr’s and to Chang’s may offer a middle ground. The first of these develops in more detail the significance of the staring eyes in the earliest bronzes and suggests that while there may have been some animistic significance in inscribing eyes on the sides of the bronzes, the subsequent elaboration of the eyes into animal forms actually follows only aesthetic criteria. Hence there may be a religious significance in the motifs taken as a whole, but not in any individual motif. The other theory suggests that the particular style of the animal motifs was derived from another arena of religious significance: ceremonial animal masks worn for the performance of ritual dances. Evidence that animal masks and costumes were common paraphernalia for religious ceremonies is abundant, and while are not able to know the specific forms that these masks and costumes took during the Shang, it is reasonable to assume that their forms were governed by both religious and aesthetic considerations. /+/

“Max Loehr’s arguments were made over half a century ago in his, “Bronze Styles of the Anyang Period” ("Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America" VII [1953], 43-53). K.C. Chang’s ideas concerning Shang shamanism were laid out in many of his publications, but the most engaging presentations are in his "Art, Myth, and Ritual: The Path to Political Authority in Ancient China" (Cambridge, Mass.: 1983)...If we mediate between these two theories, we lose some of the direct shamanistic and totemic symbolism predicated by Chang’s theory, but preserve many aspects of it. We could suggest that Loehr was correct in positing that the development of the motifs was driven by aesthetic considerations, but we can link that aesthetic to arenas of religious significance beyond the bronzes themselves, and perhaps to rites associated with shamanism.

Shang Jade

ritual tube

During the Shang dynasty and Zhou dynasties jade objects were important objects in ceremonies and rituals. Shang Dynasty circular jades were generally similar to northwestern circular jades. Late Shang pieces featured raised inner rims and thin outer edges, sets of carved concentric circles and images of curling dragons, fish, tigers and birds. The Shang also made monster-face amulets with turquoise-inlay mosaics of swirls and eyes and part-tiger-part-human marble monsters.

According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Jade, along with bronze, represents the highest achievement of Bronze Age material culture. In many respects, the Shang dynasty can be regarded as the culmination of 2,000 years of the art of jade carving. Shang craftsmen had full command of the artistic and technical language developed in the diverse late Neolithic cultures that had a jade-working tradition. [Source: Department of Asian Art, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York:The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. metmuseum.org\^/]

“On the other hand, some developments in Shang and Zhou jade carving can be regarded as evidence of decline. While Bronze Age jade workers no doubt had better tools—if only the advantage of metal ones—the great patience and skill of the earlier period seem to be lacking.If the precise function of ritual jades in the late Neolithic is indeterminate, such is not the case in the Bronze Age. Written records and archaeological evidence inform us that jades were used in sacrificial offerings to gods and ancestors, in burial rites, for recording treaties between states, and in formal ceremonies at the courts of kings.” \^/

Development of Shang Jade Artisanship

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The Shang people belonged to the Eastern Yi tribal group. They migrated from the Liao River valley to western Shandong and then west to eastern Henan, where the royal house of Shang was established. The Chou clan, like the Hsia and Chiang clans, was a member of the greater Hua-Hsia tribal group, and lived in the Wei River basin in Shaanxi. Arising from different clans, the Shang and Chou naturally developed unique cultures and ritual jade traditions. Yet these traditions also shared broad similarities due to the prolonged interaction between the two clans and the nature of their relationship as predecessor and successor to the royal house. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/ ]

Shang jade ox “From written and archeological evidence, we know that the most highly esteemed ritual objects during the Shang period were those of jade. Unlike bronze vessels, which are widely found in small- to medium-sized tombs of the nobility, jade objects were used exclusively by the highest-ranking members of society. The Shang and Western Chou not only inherited the pi disc and ts'ung ritual tube from Neolithic times, but also elevated the ritual status of the kuei tablet, such that it gradually replaced the ts'ung as the highest ranking ritual jade complementing the pi. The kuei of this time were made in two forms. One, a descendent of the axe, had a flat top edge. The other, representing a ko dagger, had a sharp symmetrical tip. The plain pi discs, plain ts'ung ritual tubes, and ko daggers in this display were all important ritual objects during the Shang and Western Chou periods. A "kuei chuan" was used during sacrificial rites as wine ladles to pour libations upon the ground. The handle-shaped objects in this exhibit are probably the handles of this sacrificial implement. \=/

“Jade sculptures or inlays depicting human figures were often mounted as finials on a long staff used by the shaman to summon the spirits of the gods and ancestors during sacrificial rites. Some jade pendants combined human and dragon designs, implying perhaps that the wearer could communicate with the heavens. Many species of animal are depicted as well — from insects, amphibians, fish, and birds to domestic animals, wild beasts, dragons, and fabulous creatures of mythology. Some of the animals are unadorned in their natural state or with simple patterns suggesting wings. Others are carved with whorl patterns signifying the movement of the primal forces of the universe. Some of the figures wear a kuei crest, representing the power of the monarch, and others have horns shaped like the character symbolizing clan ancestors (tsu). On all of the animal jades with symbolic designs or features, the eyes of the creatures are carved similar to the character for eye (mu) as written in the Shang and Chou script. The character mu is also a prominent part of the character meaning virtue (te), the original meaning of which was "heaven-sent endowment." Jades with this motif derive from the ancient belief that the ancestors of tribal clans received the gift of life from Shang-ti, the heavenly deity, through the medium of sacred animals. This is the essence of the saying that the gentleman (chun-tzu), a member of the aristocratic elite, should look to the qualities of jade as a model for human virtue.” \=/

“The first part of the late Shang dynasty (also known as the early Yin-hsu Phase) is marked by numerous sculptures of animals, which are mostly covered by various spirit-cloud patterns and designs. Few are undecorated.” Describing a pair of 10-centimeter-long rams, the Palace Museum says: “The original light green jade is visible where one of the horns of the rams was chipped, but even much of it too appears mottled brownish-yellow in color. Traces of textile and cinnabar are also still visible in the details. This pair of stocky rams appears standing with their heads slightly lowered. The compact features, such as the horns and short legs, suggest that they were carved originally from rectangular blocks of jade. The eyes were also rendered simply as round forms, and a coarse line represents the mouth. The bodies are undecorated with only abbreviated descriptions to suggest the torso, limbs, and hooves. Even traces of the carving are still apparent on the undersides.” One ram is 10.5 centimeters long, 3.9 centimeters wide and 5.3 centimeters high. The other is 10.3 centimeters long, 3.8 centimeters wide and 5.15 centimeters tall.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei\=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP;

Last updated November 2021