SHANG DYNASTY (1600 – 1046 B.C.)

The Shang dynasty, China's first true dynasty, ruled over the Yellow River Plain in the present-day provinces of Shandong, Henan, Shanxi and Hebei in northeastern China from 1600 to 1046 B.C., 1722-1122 B.C, 1554 to 1045 B.C.,. or from 1700 to 1100 B.C., depending on the source and how the dynasty's founding and defeat are defined and dated. China’s recorded history, begins with the Shang, who came into existence as a political and military force when Shang tribes overpowered tribes living on the Yellow River Plain. [Source: Peter Hessler, National Geographic, July 2003]

The Shang dynasty, China's first true dynasty, ruled over the Yellow River Plain in the present-day provinces of Shandong, Henan, Shanxi and Hebei in northeastern China from 1600 to 1046 B.C., 1722-1122 B.C, 1554 to 1045 B.C.,. or from 1700 to 1100 B.C., depending on the source and how the dynasty's founding and defeat are defined and dated. China’s recorded history, begins with the Shang, who came into existence as a political and military force when Shang tribes overpowered tribes living on the Yellow River Plain. [Source: Peter Hessler, National Geographic, July 2003]

The Shang were a Bronze Age culture that appear to have taken over a pre-existing culture in northern China rather than create a culture of their own. There is some debate as to their origin. Some say they arrived from western Asia on chariots. Others say they developed from people that had been living for centuries along the Yellow River. The Shang were ancestor worshipers who read the future from oracle bones and produced wonderful bronze vessels with finely detailed linear designs. Inscriptions indicate they hunted from chariots, killing game as big as tigers and wild oxen with composite bows, and practiced human sacrifice. Anyang in Henan Province is regarded as the capital the Shang dynasty.

Thousands of archaeological finds in the Huang He Valley — the apparent cradle of Chinese civilization — provide evidence about the Shang dynasty. The Shang dynasty (also called the Yin dynasty in its later stages) is believed to have been founded by a rebel leader who overthrew the last Xia ruler. Its civilization was based on agriculture, augmented by hunting and animal husbandry. Two important events of the period were the development of a writing system, as revealed in archaic Chinese inscriptions found on tortoise shells and flat cattle bones (commonly called oracle bones), and the use of bronze metallurgy. A number of ceremonial bronze vessels with inscriptions date from the Shang period; the workmanship on the bronzes attests to a high level of civilization. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Important themes in ancient Chinese history during the Shang and Zhou eras: 1) The Dawn of Civilization, the course of civilization and the unification of a pluralistic China. 2) The Rise of Dynastic China; 3) The Splendour of the Shang Dynasty; 4) the Great Achievements of Rites and Music; 5) the Majesty of the Imperial Capital Cities, the imperial capital cities of China's feudal dynasties; 6) Tombs of the Underworld, the tombs and mausoleums of the ancient Chinese emperors; 7), Kilns and Furnaces, the production of porcelain; 8) the Flourishing of Buddhism; 9) the Western Regions; 10) the Power of Science and Technology; 11) Moulding Metals and Fashioning Clay, bronze production techniques of the Shang and Zhou Dynasties. [Source: Exhibition Archaeological China was held at the Capital Museum in Beijing in July 2010]

Books: “Oracle Bones: A Journey Between China’s Past and Present” by Peter Hessler (HarperCollins, 2004); “Shang Civilization” by K.C. Chang (Yale, 1980). According to Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University: “There are several introductory essays on the nature of oracle inscriptions. David Keightley, the foremost Western authority in the field, has written two, of which the more accessible appears in Wm. Theodore de Bary et al., ed., “Sources of Chinese Tradition” (NY: 2000, 2nd edition). No book has been more influential for oracle text studies in the West than Keightley’s “Sources of Shang Tradition” (Berkeley: 1977). Although it is exceptionally technical, because it is very thoroughly illustrated and covers a wide range of topics it can be fun to page through even for the non-specialist. Keightley, also wrote “The Origins of Chinese Civilization” (Berkeley: 1983). His “The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China (ca. 1200-1045 B.C.)” (Berkeley: 2000) is an excellent source on Shang history, society and culture

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: PREHISTORIC AND SHANG-ERA CHINA factsanddetails.com; LEGENDARY CHINESE EMPERORS factsanddetails.com; XIA DYNASTY (2200-1700 B.C.): CHINA’S FIRST EMPERORS, THE GREAT FLOOD AND EVIDENCE OF THEIR EXISTENCE factsanddetails.com; ERLITOU CULTURE (1900–1350 B.C.): CAPITAL OF THE XIA DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; SHANG ORACLE BONES factsanddetails.com; ORACLE BONE INSCRIPTIONS factsanddetails.com; SHANG RELIGION AND BURIAL CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com; SHANG SACRIFICES factsanddetails.com; SHANG DYNASTY LIFE AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com; SHANG SOCIETY factsanddetails.com; SHANG KINGS AND GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com; BRONZE, JADE AND SHANG DYNASTY TECHNOLOGY AND ART factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Sources of Chinese Tradition” by Wm. Theodore de Bary et al., Amazon.com; “The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States” (New Studies in Archaeology) by Li Liu Amazon.com; “The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China(ca. 1200-1045 B.C.)” by David N. Keightley Amazon.com, an excellent source on Shang history, society and culture; “Daily Life in Shang Dynasty China” by Lori Hile Amazon.com; "Cambridge History of Ancient China" edited by Michael Loewe and Edward Shaughnessy Amazon.com ; "Mysteries of Ancient China: New Discoveries from the Early Dynasties" by Jessica Rawson Amazon.com ;“Oracle Bones: A Journey Through Time in China” by Peter Hessler Amazon.com; “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology” by Anne P. Underhill Amazon.com; “The Archaeology of Ancient China” by Kwang-chih Chang Amazon.com; “New Perspectives on China’s Past: Chinese Archaeology in the Twentieth Century,” edited by Xiaoneng Yang Amazon.com; “The Origins of Chinese Civilization" edited by David N. Keightley Amazon.com; “A Brief History of Ancient China” by Edward L Shaughnessy Amazon.com; “Life in Ancient China (Peoples of the Ancient World)” by Paul Challen Amazon.com ; "China: A History (Volume 1): From Neolithic Cultures through the Great Qing Empire, (10,000 BCE - 1799 CE)" Amazon.com ; "The Cambridge Illustrated History of China" by Patricia Buckley Ebre Amazon.com

Shang Dynasty Location, Population and Settlements

Shang tomb guard The central territory of the Shang realm was in present-day north-western Henan Province, near the Shanxi mountains and extending into the plains. It had cities and towns. At various times, different towns and cities served as the Shang capital. Yinxu in Anyang, Henan was their sixth and last capital and is the only one which has been extensively excavated. We do not know why the capitals were removed to new locations; it is possible that floods were one of the main reasons. The area under more or less organized Shang control comprised towards the end of the dynasty the present provinces of Henan, western Shandong, southern Hebei, central and south Shanxi, east Shaanxi, parts of Jiangsu and Anhui. We can only roughly estimate the size of the population of the Shang state. Late texts say that at the time of the annihilation of the dynasty, some 3.1 million free men and 1.1 million serfs were captured by the conquerors; this would indicate a population of at least some 4-5 millions. This seems a possible number, if we consider that an inscription of the tenth century B.C. which reports about an ordinary war against a small and unimportant western neighbor, speaks of 13,081 free men and 4,812 serfs taken as prisoners. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Anyang, the Shang capital from 1300 to 1028 B.C., was probably surrounded by a mud wall, as were the settlements of the Longshan people. In the centre was what evidently was the ruler's palace. Round this were houses probably inhabited by artisans; for the artisans formed a sort of intermediate class, as dependents of the ruling class. From inscriptions we know that the Shang had, in addition to their capital, at least two other large cities and many smaller town-like settlements and villages. The rectangular houses were built in a style still found in Chinese houses, except that their front did not always face south as is now the general rule. The Shang buried their kings in large, subterranean, cross-shaped tombs outside the city, and many implements, animals and human sacrifices were buried together with them. The custom of large burial mounds, which later became typical of the Chou dynasty, did not yet exist.

Inscriptions mention many neighbors of the Shang with whom they were in more or less continuous state of war. Many of these neighbors can now be identified. We know that Shanxi at that time was inhabited by Tibetan-Qiang tribes as well as by Ti tribes, belonging to the northern culture, and by Xianyun and other tribes, belonging to the north-western culture; the centre of the Qiang tribes was more in the south-west of Shanxi and in Shaanxi. Some of these tribes definitely once formed a part of the earlier Hsia state. The identification of the eastern neighbors of the Shang presents more difficulties. We might regard them as representatives of the Dai and Yao cultures.

Origin of the Shang Dynasty and Early Chinese Civilization

Some scholars argue that the Shang state had its beginnings in the late Longshan (Lungshan) culture (3000-1900 B.C.) that existed in the same region as the Shang. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The Shang people belonged to the Eastern Yi tribal group. They migrated from the Liao River valley to western Shandong and then west to eastern Henan, where the royal house of Shang was established. The Shang people inherited the culture of the Yi and Yueh tribal groups and produced many animal-shaped jades. The Shang civilization had elements of the Longshan culture (factsanddetails.com ), and Xia Dynasty (factsanddetails.com) [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “How did such a complex, stratified society develop? The answer is complex and not fully known. At one time, there was a consensus on this point. Sinologists generally adopted the explanation that had been offered by a social historian named Karl Wittfogel, who developed an idea known as the theory of “Oriental Despotism.”Wittfogel argued that in the “Orient” (which for him denoted an arid zone that stretched from Egypt to China) the demands of supporting large populations on parched lands necessitated the construction of massive waterworks projects to create irrigated fields. Such projects were needed for basic survival, but could not be launched without powerful control from a coordinating center. Hence, the tradition of the despot in the Orient – the absolutely powerful king. Wittfogel’s attractive theory suffered in the Chinese case from the fact that archaeology uncovered no evidence of significant irrigation work, and discovered instead that on the basis of fossil remains of plants, it appears that the climate of north China was actually quite favorable to agriculture.Moreover, the power of the Shang king does not appear to have been excessively great (regardless of the later tales concerning Zhòu’s wicked rule). If the origins of the Shang polity cannot be explained through a simple model like Wittfogel’s, how can we account for it? Before we turn to a discussion of the features of Shang society, it will be useful to survey what we know about its Neolithic antecedents.” [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

One of the basic features of the process of discovery” about the Shang Dynasty “is that everything scholars eventually learned about the Shang was initially understood in terms of how it corresponded with, or failed to correspond with the traditional account. The most elegant statement of that account appears in the “Shiji”.” The “Shiji” is monumental history of ancient China finished around 94 B.C. by Sima Qian. Note that throughout the “Shiji” account, the Shang Dynasty is generally referred to as the “Yin,” rather than as the “Shang.” The Shang Dynasty is the only period in Chinese history for which there exist two entirely independent names. Although different scholars have their own theories as to why this is so, there is no consensus as to the reason. The two most common theories are that the capital area of the Shang was called Yin, and that the alternative name derives from this. The second theory is that “Yin” was a name given to the defeated Shang people by the Zhou, denoting something like “the conquered.” Neither of these theories is completely satisfactory; however, we will tentatively adopt the first. /+/

Shang Dynasty: China’s First Literate and Culture

Dr. Eno wrote: “The Shang period is the time when China first becomes literate; many of the physical objects that the Shang people have left behind speak directly to us, when we can find and decipher them. It is harder to learn about the cultures that preceded the Shang. They are silent. Yet we have found a great wealth of objects from earlier times, and by analyzing these, we can draw a rough picture. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The Shang Culture became literate sometime during the period 1500-1250 by employing the system of ideographs that today we refer to as Chinese characters. Because characters differ from an alphabetic script in that they convey meaning without necessary reference to phonetics, the powerful tool of written language was diffused relatively easily among the various linguistic communities that occupied China at that time, enhancing early trends towards political coherence. This phenomenon may have contributed to the geographical enlargement of the socio-political reach of the Shang Culture, as the diffusion of literate culture reinforced military and diplomatic efforts to create an extended state. /+/

“The apparent linguistic homogeneity of the Shang political sphere, provided by the written rather than the spoken language, fostered a strong concept of cultural unity. The people of the Shang Culture – increasingly identifiable as “Chinese” culture – viewed the 2 expansion of the state not as an imperial process of conquest, but as a process of cultural diffusion and increasing inclusiveness towards the inevitable future of a universal state. /+/

Archaeological Evidence of the Shang Dynasty

archeologists in Yinxu in 1938

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “In studying pre-Classical China, we rely principally on materials that have been archaeologically excavated since the beginning of the twentieth century, although even when dealing with these, it is not possible to discard at least some textual sources that date from the Classical and post-Classical eras. Without the general frameworks provided by Han period histories such as the “Shiji”, it is unlikely that we could have made much sense of the archaeological materials. The way that the Shang and early Zhou have been studied by scholars in this century has always been in terms of how our newly uncovered evidence either confirms the accounts of the later texts or contradicts them.” We know “a substantial amount about late Shang culture and about the founding and first centuries of the Zhou...This is largely because China became literate in the mid-Shang, and among those objects that have been reclaimed from beneath the ground there are many that actually speak to us and address our questions (although often indirectly and in a language we still understand imperfectly). /+/[Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The earliest period of Chinese history for which we have reliable records is the latter portion of the Shang Dynasty, beginning about 1250 B.C. The reason why this is so is that archaeologists have located what may be the last royal ceremonial center of the Shang state, the city of Yin, near the present day city of Anyang, and discovered there great stores of written texts, often called “oracle bones.” These texts, which record exclusively the divinistic communications from the Shang royal house to the spirit world, convey to us detailed portraits of certain aspects of Shang life such as war, the royal family, and religious practices. Another important archaeological find concerning the Shang is a wide array of exquisitely cast bronze vessels employed in sacrificial ceremonies for the ancestors of the elite. The enormous amount of wealth and artistic refinement that is invested in these vessels (which are truly extraordinary in their beauty) represents an expression of the importance of religious clan life for the Shang elite. /+/

A number of excavations were carried out around Anyang in Henan Province in the 1920s and 30s by Li Ji, a Harvard PhD who introduced rigorous scientific method to the study of ancient China. Excavations of the Shang capital, known as Yinxu, near Anyang, began before World War II. Archaeologists explored more than 11 royal tombs and 1,000 other graves and found the foundations of temples, palaces and shrines.

Shang era archeology has not always been easy. Lady Hao’s tomb was excavated in 1976 under less than ideal conditions. The pit filled in with water as it was being excavated, because archeologists did not have access to pumps, and peasants groped for relics in the muck while they drank shots of grain alcohol to stay warm. After the excavation was completed a study session was held in which Lady Lao was scolded for accumulating wealth by taking advantage of workers.

It is believed that the Shang took their name from the first capital city they occupied. Archeologists are currently searching for this city. According to historical sources the Shang dynasty rulers were buried and a royal house of worship was erected in their first capital. Chinese-born, retired Harvard archeologist K.C. Lang believes this city is in Shangqiu (literally the “mound of Shang”) in Henan province.

Shang Conquest of the Xia Dynasty

Xia Dynasty Area

The Shang Dynasty came into being after the conquest of the Xia Dynasty, the largely-regarded-as-legendary dynasty that preceded the Shang Dynasty. Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: ““The conquest of the Xia introduces a narrative type that becomes the model for later dynastic transition stories. The key element is the evil character of the last ruler of the fallen dynasty, in this case Jie.” [Source: “Shiji” 3.91-105, Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

The Xia Dynasty was conquered by Tang the Successful. According to the Shiji:“At this time, Jie, the king of the Xia, was brutal in his government and wildly licentious. Among the feudal lords, the clan of the Kunwu rebelled. Tang raised an army and led the feudal lords. Yi Yin followed beside Tang. Tang grasped an axe and with his own hand slew Kunwu. Then he set out to attack Jie. /+/

“Tang said, “Come you masses of people, come! Hark to my words, all of you! I am but a small child, and I dare not raise a rebellion. But the Xia have committed many crimes. I have listened to your words as you said so. I hold the Lord on High in awe; I dare not fail to be upright! Now the Xia have committed many crimes, and the Mandate of Heaven is that they shall be exterminated! “Now you people, you have said, ‘Our ruler does not feel for us; he casts aside our seasonal work and is cruel in his governance.’ You have said, ‘These crimes! What should be done?’ The king of the Xia has obstructed the labor of the people and stolen from the cities of the Xia. You people have all become recalcitrant and unharmonious. You say, ‘When will this sun be extinguished? We are willing to die with you, that you shall die!’ When the character of Xia is like this, I cannot but act! /+/

“Join with me in exacting upon the Xia the punishment of Heaven and I shall attend to you all with great gifts. If you are not unfaithful, I shall not betray my words to you. But if you do not accord with the words of our oath, then I shall wipe out you and your clans without clemency!” These words he spoke to the leaders of the armies, and this became the “Oath of Tang.” Thereupon Tang said, “I am full ready for battle!” And so he was called King Wu – the Martial King. Jie was defeated on the Wastes of the Song and fled to Mingtiao, where the armies of the Xia were thoroughly routed. Tang then attacked the Thrice-Fierce tribe and captured its riches and jewels. For this, The Elder Yi and the Elder Zhong composed “Exemplary Treasures.”“ /+/

After Shang Conquest of the Xia Dynasty

According to the Shiji: “ Once Tang had conquered the Xia, he intended to remove to another place its state altar, but this was not agreed to, and he composed “The Altar of Xia.” Yi Yin made his report and the patrician lords all submitted. Then Tang ascended to the throne of the Son of Heaven and brought peace to all within the seas. [Source: “Shiji” 3.91-105, Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Tang returned to Taijuan and Zhong Hui made a report to him there. The Mandate of the Xia was officially revoked. Tang then returned to Bo and composed the “Announcement of Tang.” In the third month the king went to the eastern suburb and there he reported to the patrician lords and the assembled leaders. “Let none of you fail to work on behalf of the people. Labor hard at your affairs. Should I have cause to inflict the punishment of death upon you, you shall have no cause to complain against me. /+/

““Of old, the Emperor Yu and Gaoyao labored long abroad and achieved much for the people. The people were content then. In the east, they created the Yangzi, in the north the River Ji, in the west the Yellow River, in the south the River Huai. Once these four channels had been dredged the people had lands where they could live. Then Prince Millet broadcast the seeds and the people raised the many crops of grain. All the high officers achieved much for the people, hence their descendants were all established in hereditary office. /+/

““Of old, Chi You and the patrician lords raised confusion amongst the hundred clans. The Lord on High would not bestow anything upon them and thus they came before the court of judgment. The former kings have said, we cannot fail to be diligent! “If you do not accord with the Dao, you shall not retain your estates. You shall have no cause to complain against me.” /+/

“Thus did he charge the feudal lords. Then Yi Yin composed “All With a Single Virtue,” and Gao Shan composed “Bright in His Residence.” Then Tang changed the calendar days of the new moon and the month beginnings and altered the color of the dynastic robes of ceremony in order to exalt white. He held his court after full sunrise.” /+/

Eno wrote: “The “Announcement of Tang” is a chapter in the classic “Book of Documents”. Other titles cited in this account also refer to chapters in that text, most no longer extant. Most scholars believe that chapters in the “Book of Documents” ascribed to pre-Zhou authors were fabrications of the Eastern Zhou period. “The “Bamboo Annals”, an alternative historical record which dates from the Classical era or shortly thereafter, records that for the first six years of Tang’s reign there was a great drought. After the first few years, all music, singing, and dancing were forbidden, but it was not until the king himself went to the Mulberry Forest to pray that the drought ended. The tale of Tang’s prayer, in which he was said to offer himself to Heaven as a sacrificial victim, is recorded in a variety of texts, including the “Analects” . /+/

Shang Dynasty Power and Rule

Bronze ding with human faces

Norma Diamond wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The Shang dynasty controlled the North China Plain and parts of Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Shandong through military force and dynastic alliances with protostates on its borders. At its core was a hereditary royal house — attended by ritual specialists, secular administrators, soldiers, craftsmen, and a variety of retainers — that ruled over a surrounding peasantry.[Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

A line of hereditary Shang kings ruled over much of northern China, and Shang troops fought frequent wars with neighboring settlements and nomadic herdsmen from the inner Asian steppes. The capitals, one of which was at the site of the modern city of Anyang, were centers of glittering court life. Court rituals to propitiate spirits and to honor sacred ancestors were highly developed. In addition to his secular position, the king was the head of the ancestor- and spirit-worship cult. Evidence from the royal tombs indicates that royal personages were buried with articles of value, presumably for use in the afterlife. Perhaps for the same reason, hundreds of commoners, who may have been slaves, were buried alive with the royal corpse. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Dr. Eno wrote: “Shang society was built upon an agricultural base. The member regions of the Shang polity were generally themselves agricultural, and the enemies of the Shang tended to be nomadic societies. Unlike the nomadic peoples surrounding them, the Shang seem to have amassed surplus wealth that was very unevenly distributed within Shang society. Shang agriculture was productive, and its surplus tended over time to accumulate increasingly within the Shang elite class and at the Shang capital. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Power in the Shang was associated with walled cities where the elite dwelt, surrounded by artisans, who provided them with luxuries, and nearby farming lands for the peasants whose labor provided them with steady incomes. Shang civilization was clearly one in which wealth and power was distributed in a highly “stratified” fashion: the small elite class virtually monopolized both, and the king stood at the pinnacle of that class. /+/

Shang Dynasty and the Origins of the Chinese State

The Shang are credited by some scholars with creating the world's first state. They were governed by a caste of high priests, who called themselves Sons of Heaven and presided over human and animal sacrifices that honored ancestors and natural spirits. Under their leadership, urban craftsmen created fine ceramic and jade products. After 1500 B.C., bronze casting in China was the most advanced in the world. Shang kings ruled with absolute authority. The first Shang king, Tang, is said to have told his soldiers before battle: “If you do not obey...I will put your children to death with you.”

The geographical extent of Shang rule has been debated. Objects with Shang markings have been found over a large area but is not clear whether the Shang ruled these areas or merely influenced their culture or traded there. Some scholars believe that the area controlled by the Shang was relatively small and the term dynasty should not even be used for them.

Shang Area

Dr. Eno wrote: “It should be noted, however, that on the evidence of the oracle texts, the Shang “state” fell somewhat short of the tightly organized political entity that we usually think of “China” as being. From their shifting capital in east central China, the Shang seem to have coordinated a rather loose confederation of allied “tribes,” rather than administered a unified kingdom. While the Shang king was acknowledged as principal overlord of a wide range of groups and Shang culture set standards for the social lives of elites in all areas of this broad polity, stable political institutions do not seem to have distinguished the Shang from any preliterate predecessors whose role the Shang may have displaced. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The Shang state was not a geographically stable entity, centrally ruled from a permanent royal center. It was a shifting pattern of alliances between the frequently-relocated Shang royal house and a variety of tribal or Shang aristocratic chieftains scattered over a large area of north-central China. Shang civilization is one stage in the gradual development of a unified Chinese cultural sphere under central control, a process which culminates in the establishment of the Qin state in 221 B.C.” /+/

“During the second millennium B.C., the Shang Culture, began to absorb its neighbors into a type of loose polity that became the ancestor of what we now think of as China. Although this marks the Chinese state as a relatively late arrival compared to Mediterranean states such as Egypt and Babylonia, the growth of China during the second millennium was striking, and led to a marked span of unity and stability during the period.” Ancient China “was a political entity that was characterized by the gradual development and spread of a single dominant cultural strain that brought a certain degree of social unity to a broad region, originally peopled by tribes of various very different cultures. It was the dissolution of social and political stability during the period after 800 B.C. that led to the emergence of systematic reflective thinking about society, nature, and the supernatural about three centuries later. /+/

Shang Dynasty Military and Warfare

rendering of an ancient Chinese chariot

Dr. Eno wrote: “ The oracle texts deal extensively with issues of warfare. We learn from these texts that the Shang royal house could call on many regional rulers to serve as allies in warfare, and we see many cases of the Shang king contemplating whether or not he will campaign along with this or that regional lord, or whether he should send his troops off to aid them when they were subjected to attack. From inscriptions that were apparently divined during the course of the king’s tours or hunting expeditions in friendly lands, and which often record distances between places (in terms of travel days), we have even been able to construct rudimentary maps of the Shang “state” (which, in light of its loose political and geographical structure, we will generally refer to as the Shang “polity”). [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“We also learn about the enemies of the Shang. Tribes who were Shang adversaries are generally marked in the texts by a suffix, “fang,” meaning “region” or “outer region.” This makes the Shang adversaries easy to identify. In some cases, we see the same nomad tribes that were later to harry the Chou people. Other times, new tribes previously unknown are introduced. Overall, the military activities the bones describe confirm that the Shang was indeed a warlike polity. Warfare was a major activity of the royal house: launching major expeditions and responding to raids and territorial incursions was one of the central functions of the kingship. /+/

“Sometime during the second millennium B.C., probably during the era of the Shang Dynasty, the horse-drawn war chariot was introduced into China from the West, this technology having been diffused across Central Asia. In warfare, the leaders of the military generally rode in these two-wheeled chariots, which were drawn by two horses, and which permitted two to three men to stand abreast; the patrician warrior-leader, flanked by a driver, and often an armed escort, both of whom were themselves junior patricians. Large armies also included trained ranks of dismounted archers and large masses of infantrymen armed with spears, axes, and halberds, who were mostly untrained draftees from among the peasantry located on the lands controlled by the patrician lord leaders. During the last two centuries of the Classical era, mounted cavalry also became common. Armor, fashioned from leather or metal and usually covering only a portion of the torso, was common among the "shi" warriors. Naval technology developed only during the later Zhou in the states of the south, where navigable waterways were plentiful and control of the rivers an essential part of strategy. /+/

“Military goals included the less important one of occupying territory, which was, in general, lightly settled except near cities, and the central aim of successfully invading urban centers. Since these were defended by enormous earthen walls, this generally involved a prolonged siege, which could degenerate into a contest to see whether the inhabitants within the walls could consume their stores more slowly than the invading army could consume the crops and livestock in the fields and farms adjacent to the city walls. /+/

The Shang divined the outcome of war. One oracle bone inscription read: “Question/perhaps/king/going/fight/Hu.” Most likely meaning: "Should the king personally lead the military expedition against the Land of Hu?" The following oracular question about going to war against Hu, suggests a choice of ancestral deities who should be asked: “Question/not/recruiting/fight/Hu Land, Question/not/recruit/man/three thousand, Question/recruit/man/thousand, Question/to/T'ang/petition, Question/petition/Hu Land/to/Shang-chia.” Most likely meaning: "Should the people be recruited to fight against the Land of Hu? Should three-thousand or one thousand men be recruited? Should the petition for victory in the campaign against the Land of Hu be addressed to T'ang or Shang-chia? [Source: “Archaic Chinese Sacrificial Practices in the Light of Generative Anthropology” by Herbert Plutschow, East Asian Languages & Cultures, UCLA, Anthropoetics I, no. 2 (December 1995) -]

Shang Dynasty Weapons

Dagger axes, battle-axes and spears have been found in Shang burials. The tomb of one Shang soldier contained the remains of 15 people, 15 dogs, numerous jade objects and a bronze hand, suggesting that soldiers enjoyed high status. The Shang used composite bows as did as did other steppe horsemen. Early versions of these weapons were made of slender strips of wood with elastic animal tendons glued to the outside and compressible animal horn glued on the inside. Tendons are strongest when they are stretched, and bone and horn are strongest when compressed. Early glues were made from boiled cattle tendons and fish skin and were applied in a very precise and controlled manner, sometimes requiring a year to dry properly.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Three sets of weapons were excavated from Tomb 20 at Hsiao-t’un, offering superb evidence of the weapons and tools used by chariot soldiers in the Shang Dynasty. A complete set usually consisted of long-distance bows and arrows as well as defensive dagger axes, knives for a variety of functions, and a whetstone for sharpening. The knives and whetstones formed a set, including a jade loop to hang them. [Source: Charioting in the Shang Dynasty: Artifacts from the Horse-and-Chariot Pits at Hsiao-t'un (Collection of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Since the Neolithic Age, jade had been considered a material representing the essence of the heavens and earth. Many ritual objects were made from jade. Even by the Bronze Age, when bronze was the main medium for making ritual objects, jade managed to hold its lofty ceremonial status. In the Shang Dynasty, craftsmen instinctively embellished beautiful forms of decoration on bronze weapons to highlight the important tradition of ritual weapons. The set of jade ceremonial weapons excavated from Tomb 20 represents a good example of giving ceremonial significance to practical weapons.

First Horse-Pulled Chariots

Zhou-era chariot, perhaps such chariots

existed in the Shang era The earliest evidence of Shang dynasty armies using chariots dates to around 1200 B.C., around 500 years after Semitic tribes and mountain people on chariots invaded the Nile Valley and infiltrated Mesopotamia. Around 1500 B.C. Aryan charioteers from the steppes of northern Iran conquered India. Some scholars claim there is evidence that dates Shang chariots to 1700 B.C.. Oracle bone inscriptions suggest that the western enemies of the Shang used limited numbers of chariots in battle, but the Shang themselves used them only as mobile command-vehicles and in royal hunts. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books , Wikipedia +]

Evidence of wheeled vehicles appears from the mid 4th millennium B.C. near-simultaneously in the Northern Caucasus (Maykop culture), and in Central Europe. The earliest vehicles may have been ox carts. Starokorsunskaya kurgan in the Kuban region of Russia contains a wagon grave (or chariot burial) of the Maikop Culture (which also had horses). The two solid wooden wheels from this kurgan have been dated to the second half of the fourth millennium. Soon thereafter the number of such burials in this Northern Caucasus region multiplied. As David Anthony writes in his book “The Horse, the Wheel and Language, in Eastern Europe,” the earliest well-dated depiction of a wheeled vehicle (a wagon with two axles and four wheels) is on the Bronocice pot (c. 3500 B.C.). It is a clay pot excavated in a Funnelbeaker settlement in Swietokrzyskie Voivodeship in Poland. +

The development of the chariot had a profound impact on history. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Persians, Aryrans, Indus Valley people and ancient Chinese all had them. Chariots have been around much longer than many people think. They had been in use for almost 2,000 years when the sport of chariot racing was at its peak in ancient Rome. According to historian John Keegan "charioteers were the first great aggressors in human history." "About 1700 B.C.," he wrote, "Semitic tribes known as the Hykos, invaded the Nile Valley, and mountain people infiltrated Mesopotamia. Both invaders had chariots. The Hykos introduced their technology to the ancient Egyptians. Around 1500 B.C., Aryan charioteers from the steppes of northern Iran conquered India and later moved on to Greece. " [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Fighting chariots often accommodated two people---one rider and one archer. Early charioteers often swept down out of the mountains, encircled their flat-footed and unarmored foes, and picked them off from 100 or 200 yards away with arrows fired from sophisticated bows. Charioteers ruled the world until the 4th century B.C. when foot soldiers in Alexander the Great's army learned to withstand chariot advances by aiming their weapons at the horses first; wearing arrow-proof armor and shields; and organizing themselves into tight chariot-proof ranks.

See Separate Article ANCIENT HORSEMEN AND THE FIRST CHARIOTS AND MOUNTED RIDERS factsanddetails.com

Shang War Chariots

ancient Chinese chariot

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The war chariots of kings in the ancient Chinese Dynasty of Shang rushed across their great land. Amongst the whinnying of warhorses that pulled them, they magnificently blazoned page after page in the brilliant history of these rulers. Shang craftsmen used precious bronze and turquoise to meticulously refine and decorate these noble chariots and steeds, also using their skills to show off the pomp and glory of the royal dynasty in state ceremonies. In addition, precious chariots and steeds were buried along with the royal tombs, serving to represent and protect the nobility of their occupants in the afterlife. [Source: Charioting in the Shang Dynasty: Artifacts from the Horse-and-Chariot Pits at Hsiao-t'un (Collection of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

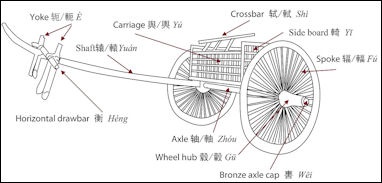

“In the Shang Dynasty, the construction of chariots represented one of the high technologies of the period. Everything from the selection of wood to the design and production of these vehicles was complex and precise in terms of processes and techniques used. In addition to the woodworking tradition, which had focused on carving since the Neolithic period, the production of chariot wheels also required the development of wood-bending techniques. In order to ensure that the assembled structure would remain stable and hold together, precise calculations were needed along with tenon jointing techniques. \=/

“An important object in the life of nobility at the time, the chariot also had to be opulently decorated. After the chariot was constructed, it required cushioning to make riding in the carriage more comfortable. Colored lacquer could also be painted on the wood of the body to make it appear livelier, and special cast bronze ornaments were made to beautify it. These decorative pieces, when placed in appropriate and obvious places on the chariot, highlighted the importance of the vehicle.Chariot Harnesses of the Shang Dynasty.” \=/

Most Shang chariots buried underground disintegrated over time. “In April 1936, in the settlement of Hsiao-t’un (near An-yang city, in modern Henan province) two young archaeologists from the History and Philology Institute of the Academia Sinica, Shih Chang-ju and Kao Ch’ü-hsün, discovered a Shang royal horse and chariot pit in what was the palatial district of the flourishing site of the Shang capital of Yin some three thousand years ago.” \=/

Origin of Shang Chariots and Horses

Zhou-era chariot fitting

Some scholars believe chariots originated in the Caucasus and spread from there, with the help of the West Asia- and Siberia-based Andronovo culture, to Central Asia and China around the 2nd millenium B.C. According to “The Origin of the Indo-Iranians”: “During the 15th and 14th centuries B.C., chariots appeared in the Trans-Caucasus where Bronze models of the Eastern type have been discovered (Pogrebova).” [Source: “The Origin of the Indo-Iranians” by Elena E. Kuz’mina, Elena Efimovna Kuz'mina, J. P. Mallory, 2007]

“he horse as well as the chariot came into the southern part of Central Asia from the Urals in the beginning of the 2nd millenium B.C. which is uncontrovertibly documented by the finds in Zardcha-Halifa and Dzarkutan of cheek-pieces of a specific type which have also been found in Sintashta, Kamenny Ambar and Krivo Ozero. Probably the same is valid for the emergence of the horse in the BMAC [Central-Asia-based Bactria-Margiana culture) indicated by the decapitated foal and the horses in the cemetery of Gonur and of a horse in the settlement of Dashly 19 and of the images of horses (or their heads) on the ceremonial bronze axes from the early 2nd millenium B.C. and from the Mahboubian collection.

“The horse-drawn chariot spread to China during the second half of 2nd millenium B.C. with the Andronovan tribes. This assertion is supported by the find of a bronze bit with cheek-pieces with projections going back to the earliest Andronovan prototypes. This has been found in the cemetery of Nanshangen, grave I, dating from the end of the 2nd millenium B.C. by the objects of Siberian type.”

Well-preserved chariot and horse remains were unearthed in Luoyang City, central China's Henan Province, where excavation revealed four horse and chariot pits dated to the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-256 B.C.). News of this discovery was announced in September 2011. The main pit contains five chariots and 12 horses. Archaeologists say that the animals were not entombed alive.The pits have well-preserved bronzeware and ceramics. [Source: Xinhua, September 1, 2011]

The abstract for the article "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the origin of the Chinese domestic horse" reads: “Domestic horses played a pivotal role in ancient China, being used mainly in agriculture and transport, especially in military purposes (Chen, 1994). However, the geographic origin of Chinese domestic horses remains controversial. Zooarchaeological data show that abundant domestic horse remains appeared suddenly in China at the sites of the Shang Dynasty (ca. 3000 BP). Prior to the Shang Dynasty, there are few records of domestic horses. Excavation of thousands of Neolithic and early Bronze sites in China yielded only a few sporadic fragments of horse tooth and bone at a limited number of sites, and it is difficult to determine whether the remains are those of wild or domestic horses (Chen, 1999). The absence of evidence for the early stages of domestication, coupled with the sudden appearance of horses around 3000 BP, have led scholars to suggest two hypotheses. First, that domestic horses were imported into China from the Eurasian steppe via that Gansu and Qinhai provinces (Yuan and An, 1997), or, second, that horses underwent autochthonous domestication in China during the Later Neolithic (ca. 4000 BP) or perhaps even earlier, and Przewalski horses were proposed as the ancestors of Chinese domestic horses (Wang and Song, 2001; Zhang, 2004). [Source: "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the origin of the Chinese domestic horse" Cai, D. W.; Tang, Z. W.; Han, L.; Speller, C. F.; Yang, D. Y. Y.; Ma, X. L.; Cao, J. E.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, H. (2009).(PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science 36 (3): 835–842. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.11.006

Decline of Shang Dynasty and Rise of the Zhou

The conquests of late Shang added more territory to the realm than could be coped with by the primitive communications of the time. When the last ruler of Shang made his big war which lasted 260 days against the tribes in the south-east, rebellions broke out which lead to the end of the dynasty. Weakened by corruption and decay, the Shang dynasty was overpowered in 1050-25 B.C. by the Zhou, a Chinese dynasty to the west that also knew how to effectively use horses, chariots and composite bows. The 29th and final Shang king, Di Xin, was known for his indulgences, appetites and whims. He reportedly hosted orgiastic parties around a palace pool filled with wine and ordered those who displeased him to be taken away and executed. Historians doubt the veracity of these tales, namely because they come from Zhou and Han dynasty sources, which likely portrayed dynasties before them as evil to make themselves look good.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The Shang people belonged to the Eastern Yi tribal group. The Chou clan, like the Hsia and Chiang clans, was a member of the greater Hua-Hsia tribal group, and lived in the Wei River basin in Shaanxi. Arising from different clans, the Shang and Chou naturally developed unique cultures yet these traditions also shared broad similarities due to the prolonged interaction between the two clans and the nature of their relationship as predecessor and successor to the royal house. It is recorded that when the army of King Chou (the last Shang ruler) was defeated, the king donned his shaman vestment sewn with many small jade animal figurines and committed suicide by fire. The king, who also held the position of chief shaman, may have hoped that the essential vital force of the jade and the power of the animals represented in this precious mineral would help his spirit find its way to heaven. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/ ]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “There are a considerable number of inscriptions bearing on the Zhou people dating from the reign of Wu-ding, about 1200 B.C. One text refers to the Zhou as “Zhou-fang,” indicating that the Zhou could be pictured as an adversarial or alien people, all other instances drop the fang suffix. Perhaps at this time, the Zhou were relatively new members of the Shang polity. It is believed that during this period, the Zhou people inhabited an area in the Fen River Valley, northeast of the bend of the Yellow River. The Shang were in regular, but not close contact with them. The Shang king issued orders to the Zhou, divined about the welfare of the Zhou troops and commanders, inquired about the likely success of the Zhou hunts, and bestowed the title Hou upon their leader. “On the other hand, the King never visited the realm of the Zhou to tour or to hunt, nor called upon Zhou manpower to aid Shang public works. The king was concerned for the health of the Zhou ruler, but never divined about the success of the Zhou harvests. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

See Separate Articles SIMA QIAN ON THE EARLY ZHOU KINGS AND THE DEFEAT OF THE SHANG BY THE ZHOU factsanddetails.com ; ZHOU (CHOU) DYNASTY (1046 B.C. to 256 B.C.) factsanddetails.com

Yin Xu (Xiaotun, Anyang): the Shang Dynasty Capital

Yin Ruins (Xiaotun village in Anyang, 120 kilometers north Kaifeng, 150 kilometers north-northeast of Zhengzhou) is the home of the last capital of the Shang Dynasty (1700-1100 B.C.) More than 3,300 years ago, Shang King Pangeng moved his capital to Yin (known today as Yinxu, Yin Xu and the Yin ruins), which served as the capital for 12 kings of eight generations for 225 years, and created the splendid Yin-Shang civilization. After King Wu of the Zhou Dynasty (?-1043 B.C.) sent armed forces to suppress Zhou and eliminate the Shang, Yin gradually became the Yin Ruins in history.

The ruins of Yin, discovered in 1899, is one of the oldest and largest archeological sites in China. The ruins have yielded tombs, foundations of palaces temples, jade carvings, lacquer, white carved ceramics, and high-fired, green-glazed ware. The Yin Ruins became famous because of a large number of oracles bones — inscriptions on animal bones or tortoise shells — found that there that were used for divination by Shang kings and contains some of earliest known examples of Chinese characters, Excellent bronze wares were also excavated from the ruins, of which Simuwu recatangular ding (cooking vessel), weighing 437.5 kilograms, the largest ancient bronze ware in the world.

The Yin Ruins covers an area of 36 square kilometers, and is divided into the palace zone, royal tomb zone, graveyard, handicraft workshop zone, civilian residential zone, etc. It is the first site of an ancient capital city confirmed by historical documents, oracle bone inscriptions and archaeological excavations in Chinese history. Tens of thousands of bronze, jade and ivory wares excavated from the Yin Ruins show various shapes and postures, displaying the top carving and cast skills in the Yin-Shang period. They will make viewers gasp in admiration.

See Separate Article KAIFENG AND YIN XU: CAPITALS OF THE SONG (960-1279) AND SHANG (1700-1100 B.C) DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com

Shang sites

Shang Sites and Phases

Yuan Guangkuo wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: “In 1956, Zou Heng made the first attempt to divide the whole Shang culture into stages. He later made a finer chronological division of Shang culture based on new archaeological findings (Zou 1980). He divided the Erligang period into two stages referred to as Erligang Lower Layer and Erligang Upper Layer. This division is currently accepted by archaeologists. On the basis of new radiocarbon data, early Shang culture dates from around 1600 to 1300 B.C. (Expert Team 2000 : 63–64). [Source: “Discovery and Study of the Early Shang Culture” by Yuan Guangkuo, A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, Edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing, 2013 ~|~]

“Because of the continuous cultural development from the first stage represented by the early Shang city of Zhengzhou to the later stage represented by the Xiaoshuangqiao site about 20 kilometers from Zhengzhou, the consensus is that they belong to the same culture. But we still have a short chronological gap between the early Shang remains at Xiaoshuangqiao and the later early Shang remains at Anyang in northern Henan represented by the Huayuanzhuang site, more commonly referred to as Huanbei (Guangming Daily 2000). Given the similarities in artifacts and the chronological information so far, I tentatively conclude that Huanbei should be considered an early Shang site.” Huanbei has been dated to the 14th century B.C. and was discovered in 1996. Mapping of the area has revealed an entire city, with walls that enclosed nearly two square miles.

“The results of intensive archaeological research during the past few years make it possible to divide the early Shang culture from about 1600 to 1300 B.C. into four phases. The first phase is represented by the inner walled city at the site of Zhengzhou and the small, walled inner city at the site of Yanshi. The second phase is represented by the outer walled areas at the sites of Zhengzhou and Yanshi. In other words, people expanded these city sites in the second phase by constructing much larger rammed-earth walls that surrounded the smaller walled areas. The third phase is represented by Xiaoshuangqiao, and the fourth phase is represented by Huanbei. ~|~

“1) Sites from the first phase of early Shang culture include the walled, urban center of Zhengzhou, the walled urban center at Yanshi, and deposits at the Erlitou site that lie on top of those from the Erlitou period. These early Shang sites are distributed in west-central Henan province, roughly overlapping the main region of the preceding Erlitou culture. ~|~ 2) The second phase of early Shang culture includes the expanded Zhengzhou walled city, the expanded Yanshi walled city, the Dongxiafeng site, the walled city site of Yuanqu, and the walled city of Fucheng (Yuan and Qin 2000). To the north, the early Shang culture in this period reached the north bank of the Yellow river and to the south, it stopped along the north bank of the Yangzi river. It extended as far as the central Shaanxi plain to the west, into eastern Henan. The southeastern boundary is the western Yangzi river–Huai river region. 3) The excavated sites thus far dating to the third phase of the early Shang culture include Zhengzhou, Xiaoshuangqiao, and Daxinzhuang in the Jinan city area, Shandong province. 4) During the fourth phase, early Shang culture expanded significantly to the north and east.

“Shang sites have been found at the eastern foot of the Taihang mountains and some even as far as the Huliu river valley north of the Taihang mountains. The excavated sites thus far are Huanbei at Anyang, and two sites in Hebei province: Guitaisi (Beijing Daxue and Handan 1958) and Taixi (Hebei Provincial 1985). It should be noted that the geographic region of early Shang settlements is smaller than the area that would have been impacted by early Shang culture. Artifacts with early Shang stylistic elements have been found at sites from neighboring cultures such as Baiyan in central Shanxi province, Zhukaigou in the southern Ordos plateau, Xiuwan at Tongshan in Jiangsu province, and Wucheng in the middle Ganjiang river–Poyang lake region. ~|~

Shang and America Connection?

Chinese Shang scholar Han Ping Chen believes that the founders of the Olmec civilization in Mexico---which emerged suddenly in 1,200 B.C. and influenced the Maya and Aztec civilizations---was influenced by the Shang dynasty. He bases his theory on the fact that Mesoamerican jade blades, called celts, have markings that are almost identical to Shang-era Chinese characters.

After examining six polished celts on a trip to the United States in 1996, Han exclaimed, "I can read this easily. Clearly, these are Chinese characters." He also asserted that achievements made by early New World civilization was made with help from the same people who introduced the Chinese characters. [Source: U.S. News and World Report]

Other similarities between Chinese and ancient Mesoamerican cultures include the resemblance of the Aztec board game atolli and the Asian game parcheesi; the custom of placing jade beads in the mouthes of the deceased; and the fact that important religious deities were inspired by tigers-jaguars and dragonlike creatures.

It is not impossible for an ancient vessel to have been blown off course across the Pacific to America. Ancient Chinese mariners were highly skilled. Some anthropologist believe they sailed to Indonesia and islands in the Pacific 2,000 years ago. It also quite possible that the ancient Mesoamerican cultures independently developed stuff that was similar to Chinese stuff.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; Shang tomb guard, Brooklyn College; Chariot, Ohio State University; Oracle Bones, Brooklyn College; Bronze wine vessel, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Excavation of Tomb of of Fu Mao, University of Washington;

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021