READING ORACLE BONE INSCRIPTIONS

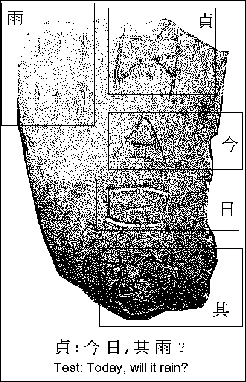

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “A complete oracle bone or shell inscription usually includes the following sequence of information: 1) Preface: Includes the time of divination and the name of the person executing the divination. 2) Charge: The question asked at the divination. 3) Prognostication: The prediction of the Shang king on the basis of the divined omen. 4) Verification: What actually came true. Of these, the prognostication and verification were often omitted, leaving only the preface and charge.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/ ]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The grammar of oracle texts does not indicate that the words were intended as questions, rather than as statements. Most scholars take them to be statements, which the spirits may confirm or fail to confirm. In these readings, I phrase the translations as clerical records: statements about the divining process. A very large percentage of the oracle texts are structured on the basis of a simple divination form. This form included several items: the date, the diviner, and the “charge,” which was the statement or question that was offered to the spirit world for response. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“A simple, typical inscription might look like this (Transcribing character by character, first into modern Chinese character equivalents and then word for word into English we get): “”Ding-si”crack Yin divine King guest-ritual Father Ding offer-up behead Qiang thirty butcher five penned-sheep no fault” Translating this into ordinary English we would get: On the day “ding-si”we made cracks and Yin divined about whether if the King were to perform a guest ritual for Father Ding and offer to him thirty captives from the Qiang nomad tribe as well as five penned sheep these actions would be without fault. /+/

“The day “ding-si”” refers to the sixty day calendar cycle of the Shang, which is explained in the previous section. Yin was the name of a prominent diviner during the reign of Zu-“geng”(c. 1180-1170), a son of the king Wu-ding (“Father Ding”) whom we met in Keightley’s reconstruction. In this inscription, the king, probably Zu-“geng”, is considering pleasing his father through assorted decapitations, including a substantial number of captives from a prominent tribe of Shang adversaries. An attractive feature of Shang culture was the dutiful slaughter of surplus captives for the pleasure of natural and ancestral spirits. /+/

“More elaborate inscriptions do exist, and some of these include features entirely absent from the example given above. In some cases, after the “charge” to the spirits, we encounter a section that begins, “The King divined,” and records the interpretation of the crack that the king made at the time of the divination, the “prognostication.” Since we are ourselves unable to understand how the cracks related to the divination, this is a very helpful gloss for us to have. In addition, in some of the cases where the king’s divination is recorded, the text will also provide an account of what actually transpired relative to the divination: the “verification.” (Shocking as it may seem, according to the records of his own divination recorders the king was always right!) /+/

This sample relates to a toothache: 8. Crack.making on “yiwei”(day 32), Gu divined: “Father Yi (the twentieth Shang king, Xiao Yi, the father of Wu Ding) is harming the king.” 9A. Divined: “Grandfather Ding (the fifteenth king, father of Xiao Yi) is harming the king.” 9B. Divined: “It is not Grandfather Ding who is harming the king.” 10. Divined: “There is a sick tooth; it is not Father Yi ( = Xiao Yi, as above) who is harming (it/him).” [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

This sample relates ion to a whether or not to build a settlement: 19A. Crack.making on “renzi”(day 49), Zheng divined: “If we build a settlement, Di will not obstruct (but) approve.” Third moon. 19B. Crack-making on “guichou”(day 50), Zheng divined: “If we do not build a settlement, Di will approve.” 20A. Crack-making on “xinchou”(day 38), Que divined: “Di approves the king (doing something?).” 20B. Divined: “Di does not approve the king (doing something?).”

Books: “Oracle Bones: A Journey Between China’s Past and Present” by Peter Hessler (HarperCollins, 2004); “Shang Civilization” by K.C. Chang (Yale, 1980). According to Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University: “There are several introductory essays on the nature of oracle inscriptions. David Keightley, the foremost Western authority in the field, has written two, of which the more accessible appears in Wm. Theodore de Bary et al., ed., “Sources of Chinese Tradition” (NY: 2000, 2nd edition). No book has been more influential for oracle text studies in the West than Keightley’s “Sources of Shang Tradition” (Berkeley: 1977). Although it is exceptionally technical, because it is very thoroughly illustrated and covers a wide range of topics it can be fun to page through even for the non-specialist. Keightley, also wrote “The Origins of Chinese Civilization” (Berkeley: 1983). His “The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China (ca. 1200-1045 B.C.)” (Berkeley: 2000) is an excellent source on Shang history, society and culture

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: PREHISTORIC AND SHANG-ERA CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINA: THE HOME OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST WRITING? factsanddetails.com; SHANG DYNASTY (1600 – 1046 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; SHANG ORACLE BONES factsanddetails.com; SHANG RELIGION AND BURIAL CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com; SHANG SACRIFICES factsanddetails.com; SHANG DYNASTY LIFE AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com; SHANG SOCIETY factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Oracle Bones: A Journey Through Time in China” by Peter Hessler Amazon.com; “Sources of Chinese Tradition” by Wm. Theodore de Bary et al., Amazon.com; “The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China(ca. 1200-1045 B.C.)” by David N. Keightley Amazon.com, an excellent source on Shang history, society and culture; “Daily Life in Shang Dynasty China” by Lori Hile Amazon.com; “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology” by Anne P. Underhill Amazon.com; “The Archaeology of Ancient China” by Kwang-chih Chang Amazon.com; “New Perspectives on China’s Past: Chinese Archaeology in the Twentieth Century,” edited by Xiaoneng Yang Amazon.com; “The Origins of Chinese Civilization" edited by David N. Keightley Amazon.com

Contents of Oracle Bone Inscriptions

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: The subject matter of oracle bone inscriptions “is composed primarily of "pu-ts'u" (divinatory words), that is, the records of Shang royal divinations. There are also a number of inscriptions that record events. Shang royal divinations touched on almost every topic of importance at the time, such as what to sacrifice in worship to the gods or ancestors, whether it would rain on a particular day, whether the harvest would be good, whether it would be safe to go to war or out hunting, the nature of good and bad omens envisioned in illness and dreams, the timing of childbirth, and the prediction of good fortune or disasters yet to come. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw]

oracle bone inscriptions

“These form the basis of what are known as oracle bone inscriptions. In addition to recording the practice of divination, sometimes events unconnected with sacrificial worship were also recorded on turtle shells or animal bones. Nevertheless, the name "chia-ku wen" (oracle bone inscriptions) is used to refer to both divinatory inscriptions and event records.” \=/

The following are some of the subjects addressed in oracle bones. 1) Sacrifices: An oval plastron piece (B4747) was cut from the dorsal side of a turtle. The hole suggests that it was once bound together. The inscription gives the date as well as the name of the diviner, and the divination asks whether three or five oxen are appropriate for a certain sacrifice. \=/

2) Relationships with Other States: The relation between Shang rulers and neighboring states was often complex. Whether good or bad, it often included tribute, negotiations, or even war. The long inscription of 62 characters on this piece (A2416) records that King Hsin will go on a punitive expedition with his nobles against the state of Yu and records his prayers for victory. 3) Settlement Building: Few oracle bone inscriptions deal with the foundations for building. The king in the inscription on this plastron (B3212) asked whether to establish a new walled settlement. \=/

4) Weather: Many oracle bone inscriptions deal with the weather, which is intimately related to agriculture, royal inspection tours, and hunting conditions. The inscriptions on this plastron (C63) inquire as to whether it will rain on that or the following day, but no reasons are given. 5) Agriculture: In modern and especially in ancient times, food is of paramount importance for survival. The Shang was an agrarian state, and a good or poor harvest had a great impact. Agriculture was therefore naturally of great concern to the Shang kings. This plastron (B3287) asks whether the "eastern lands" will have the favor of the heavens for a good harvest. 6) Hunting Expeditions: The Shang kings often made royal tours and hunting trips. These were events of political and military importance as well as leisure. This piece (A3350) prays for good luck on the dates and at the places for hunting. \=/

7) Religion: In ancient times, two activities were of paramount importance to Shang leaders; sacrifices and military affairs. The contents of oracle bone inscriptions reveal Shang ideas about the spirits and cosmos. Of the six inscriptions on this plastron (C73), four of them inquire as to whether the spirits will bring poverty to the capital. 8) Ailments: Illness to the Shang kings was thought to be caused by ancestors, and the cure usually involved ceremonies. The inscriptions on this plastron (B5405) refer to the king's ringing in the ears and the method divined to cure it. \=/

Oracle Bone Inscriptions on Warfare

Oracle character

Many oracle bone inscriptions deal with war. Divination often inquired into the time, place, and leadership for battle as well as omens for victory or defeat. In one set of inscriptions on piece C16, the king asked which officer should lead a punitive expedition. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Another reads: On "dingmao" (day 4) divined: “If the king joins with Zhi [Guo] (an important Shanggeneral) to attack the Shaofang, he will receive [assistance].” Cracked in the temple of Ancestor Yi (the twelfth king). Fifth moon. [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition”, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

23 reads: [Divined:] “The Fang (enemy) are harming and attacking (us); it is Di who orders (them) to make disaster for us.” Third moon. “24A: Divined: “(Because) the Fang are harming and attacking (us, we) will raise men.” 24B: Divined: “It is not Di who orders (the Fang) to make disaster for us.”

Oracle Bone Inscriptions on Childbearing

oracle character

The day on which a royal consort would give birth and the sex of the baby were matters of great interest to the Shang king. Among the inscriptions on this plastron B1052, some inquire as to the month of a baby's birth. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei ]

15A reads:. Crack making on “jiashen”(day 21), Que divined: “Lady Hao’s (a consort of Wu Ding) childbearing will be good.” (Prognostication:) The king read the cracks and said: “If it be on a “ding”.day that she give birth, there will be prolonged luck.” (Verification:) (After) thirty-one days, on “jiayin”(day 51), she gave birth; it was not good; it was a girl. [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition”, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

15B reads: (Prognostication:) The king read the cracks and said: “If it be a “ding”.(day) childbearing, it will be good; if (it be) a “geng”-day (childbearing), there will be prolonged luck; if it be a “renxu”(day 59) (childbearing), it will not be lucky.”

Names, Titles, and the Dating of Oracle Bone Inscriptions

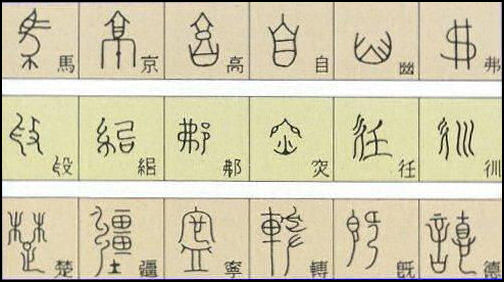

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “ One of the causes of the slow progress of scholars who initially undertook to decipher the oracle inscriptions was the puzzling meaning of the characters that we recognize today as diviner names. Once these were understood, not only did reading the texts become vastly easier, but a key tool to dating the texts was provided. All the inscriptions that include the name of a single diviner may thus be assumed to date from a single period of a few decades. This was the first clue that allowed scholars to begin to sort the inscriptions chronologically. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

Oracle divination

“The second clue concerned the royal ancestors. A very large proportion of the oracle texts are devoted to issues concerning ancestral sacrifice. Shang kings were reluctant to mount expensive sacrificial ceremonies without first alerting the spirits through divination of the date of the sacrifice and the menu. “On the day “gui-you”we made cracks, He divining about whether on the coming “jia” day we should offer steamed grains to Father “jia” ”: no type of inscription is more common than this sort (we can almost hear Father “jia” groan, “Not millet again!”). /+/

“The object of this sacrifice, Father “jia” , would have been the father of the reigning king.We also note that, during the time that the Ho in this inscription was a diviner, sacrifices were offered to “Mother “Wu”.” Other inscriptions pair together a “Grandfather “jia” ” and a “Grandmother “Wu”,” and from this we can deduce that these date from the reign of the grandson of this couple, a former king and queen of the Shang. Throughout the inscriptions, the titles of departed royal spirits are referred to in this way, with their generational marker titles changing as they recede into the past. By correlating the ancestor titles with the diviner names, it became possible to sort a very large proportion of the texts into chronological periods, and, since the individuals who inscribed the bones tended to write in distinct styles, additional texts could be attached to the sorted groups according to “handwriting” criteria. /+/

“As you may have observed in the “Shiji” account of the Shang royal house, the Shang moved the site of their capital city with some regularity during most of their history. The last of these moves seems to have taken place under the rule of King Pan-geng, who moved the Shang capital to the Xiaotun site where the oracle texts were recovered. Thus we assume that all the texts we have recovered date from the period of Pan-“geng”’s reign and after. In fact, detailed research has now indicated that none of the inscribed bones so far recovered date from before the reign of Wu-“ding”, who ruled approximately 1200-1180. Therefore, the oracle texts that we now possess were generated over a period of about 150 years, from c. 1200 until the fall of the Shang in 1045. /+/

“Once the texts had been sorted into groups, it became possible, by relating king titles to the account in the “Shiji”, to see that the “Shiji” record of the Shang kings was remarkably close to that indicated by the bones. At that point, scholars were finally able to order most of the inscriptions in chronological sequence. /+/

Changes to Oracle Bone Texts Over Time

Dr. Eno wrote: “ Once the oracle texts had been sorted chronologically, scholars observed that there were certain differences in the practices and apparent attitudes of the kings and diviners during different periods of the late Shang. For example, the inscriptions dating from the era of Wu “-ding”include a very broad range of topics and give every indication that those divining are deeply interested in the responses that the spirits may offer. We have already seen that Wu “-ding”troubled the spirits to explain the root causes of his toothaches. In addition, he queried them concerning the following topics: warfare, harvests, hunting, the weather, royal childbirth, whether he should issue certain commands, his headaches, the safety of the upcoming night or ten-day week, and issues of sacrifice. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“All indications are that Wu-“ding” was a particularly charismatic leader: only he and Pan-“geng”stand out as effective rulers in the “Shiji”’s descriptions of the late Shang kings, and it appears to have been Wu-“ding”, rather than Pan-“geng”, who established at least the great ceremonial complex at Xiaotun that included the massive tombs of the late Shang kings and queens. In addition, it is in the inscriptions from Wu-“ding”’s period that we see the greatest number of records of Shang conquests in war, and the decapitation of thousands of captives in honor of the ancestors. Wu-“ding” was, most likely, one of the great rulers of ancient China. And like most of these great rulers, he appears to have been highly religious (we might prefer the term superstitious). During his reign, oracle inscriptions are at their most detailed and colorful. /+/

“After Wu-“ding”’s death, his successors adopted varying attitudes towards the function of divination. Wu-“ding”’s son, Zu-“geng”, continued to place emphasis upon bone and shell oracles, but after his time, the practice began to change from a lively form of communication with the spirits to a far more routine ritual associated with a set schedule of ritual sacrifices. By the time we reach the last of the Shang kings, Di-“xin”, also known as Zhòu, the oracle texts have become a voluminous but not very interesting record of the basic sacrificial calendar of the Shang.” /+/

What Can be Learned from the Oracle Bones (And What We Can’t)

oracle bone inscriptions

Dr. Eno wrote: “ The Shang oracle texts constitute a spectacularly rich mine of information about a period of ancient China that has traditionally been shrouded in mystery, and the information they provide is contemporary and unedited – a stark contrast to the problems we have with the data for the Classical period. The field of oracle text studies is so alluring and rewarding that for generations some of the finest scholars in China, Japan, and the West have devoted all their energies to sorting out its many puzzles. However, the window on the Shang that the bones provide is actually quite narrow. These texts picture events entirely through the perspective of divinatory significance. For all the apparent breadth of the divinations of the more religiously obsessed rulers, such as Wu-“ding”, most of the questions “we”would like to pose to these ossified oracles are left unanswered. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“What follow are a list of a few topics with a brief description of the ways in which the oracle texts relate to them. 1) “”Religion”. The oracle texts give us an enormous amount of data concerning the royal religion of the Shang, but interpreting that information is often difficult.We meet scores of deities in the texts, but who they are and what they are believed to do is often unclear. We encounter perhaps a hundred forms of sacrificial ritual, but it is very difficult to know how they differed and how they formed a system. The difficulties of interpretation of this richest of all areas of oracle information can be captured simply by saying that we still do not know whether the Shang conceived of a high deity with subsidiary gods or only of a world of spirits acting independently. We do not know the organizational structure of the Shang supernatural.

2) “”The Royal House”. The texts introduce us to all the significant members of the Shang royal house once they are dead, but tell us very little about the living. They refer at times to living queens and concubines and to the princes of the Shang, but the information they provide is limited. Nevertheless, we are able to piece together some structured information, such as the career of the queen Fu-hao, which we will examine later, that give us important insight into the royal family and its behavior. In addition, as we will see, the structure of the royal ancestors may provide important information concerning Shang kinship. /+/

3) “”Warfare and the state”. The oracle texts deal extensively with issues of warfare. We learn from these texts that the Shang royal house could call on many regional rulers to serve as allies in warfare, and we see many cases of the Shang king contemplating whether or not he will campaign along with this or that regional lord, or whether he should send his troops off to aid them when they were subjected to attack. From inscriptions that were apparently divined during the course of the king’s tours or hunting expeditions in friendly lands, and which often record distances between places (in terms of travel days), we have even been able to construct rudimentary maps of the Shang “state” (which, in light of its loose political and geographical structure, we will generally refer to as the Shang “polity”). /+/

“We also learn about the enemies of the Shang. Tribes who were Shang adversaries are generally marked in the texts by a suffix, “”fang”,” meaning “region” or “outer region.” This makes the Shang adversaries easy to identify. In some cases, we see the same nomad tribes that were later to harry the Chou people. Other times, new tribes previously unknown are introduced. Overall, the military activities the bones describe confirm that the Shang was indeed a warlike polity. Warfare was a major activity of the royal house: launching major expeditions and responding to raids and territorial incursions was one of the central functions of the kingship. /+/

4) “”Agriculture, the economy, and social structure”. The oracle texts provide some relevant information in this regard. Their queries or tentative statements to the spirits indicate the state of the harvests, the types of grain being offered, and their expectations of natural disasters. But the information tends to be indirect and sparse.We hear about types of tribute gifts that arrive at the capital because the king will occasionally wonder whether they will arrive, but there is little systematic information on trade. (The most obvious information is in the form of the large number of turtle shells which were procured from the southeastern coast areas for the purposes of divination.) We learn something about animal husbandry by the inventories of sacrificial animals offered to the ancestors, and queries about the royal hunt and its catch give us information about wild animals and the diet of the Shang privileged classes. /+/

“Perhaps the most important type of information we encounter concerning social organization involves the evidence of the king’s power to mobilize labor, particularly for two massive types of undertakings: warfare and the construction of city walls. The texts frequently refer to the “multitudes,” or masses, and while we are unclear precisely to whom this refers and under whose control these people were (were they peasants or permanent armies? – under the control of the Shang king or of regional allied lords?), these masses of people were certainly viewed principally as a manpower resource, without high social standing.In sum, by confirming the basic historicity of the “Shiji” accounts of the Shang, the oracle texts have provided us with our first real factual knowledge of this long period. However, the nature of the data they provide is so selective and skewed to our own interests as historians that the image of the Shang that they project remains oddly distorted and analytically challenging. /+/

Research on Oracle Bone Inscriptions

inscribed bone

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “As mentioned previously, the first person to note the importance of oracle bones was Wang Yi-jung (1845-1900). With the help of his friend Liu Eh, oracle bone inscriptions were discovered in 1899. In 1900, however, Wang died during the Boxer rebellion, and his collection of oracle bones came into Liu's hands. The first book published with rubbings of oracle bones was "T'ieh-yun ts'ang kui" (T'ieh-yun's Turtle Collection), completed in 1903 by Liu Eh (1857-1909). In his book, representing rubbings of more than a thousand oracle bones from his collection of five thousand, Liu Eh correctly identified the inscription as "knife-inscribed" writing of the Yin (late Shang dynasty, 14th-11th century B.C.) and was even able to recognize a number of characters (including those for the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches as well as numerals). The first person to undertake the systematic research of oracle bone inscriptions was the late Ch'ing scholar Sun Yi-jang (1848-1908). His work "Ch'i-wen chu-li" (Examples of Oracle Bone Inscriptions), though containing some misinterpretations of Shang culture, laid the foundations for future studies of oracle bone inscriptions. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Although the latter two recognized that oracle bones represented Shang divinatory writings, it was only with Lo Chen-yu (1866-1940) and Wang Kuo-wei (1877-1927), that the contents of the inscriptions became clear as the divinations by the late Shang royal house. Lo Chen-yu purchased more than 30,000 pieces of oracle bone inscriptions and, between 1913 and 1916, published four important books based on his studies. Wang Kuo-wei, a major scholar of Western and Chinese subjects, published in 1917 "Yin pu-ts'u chung so chien hsien-kung hsien-wang k'ao" (An Investigation of Ancestors and Kings as Seen in Yin Divinatory Inscriptions), which used oracle bone inscriptions to confirm the written histories of the late Shang. \=/

“Although the succession of Shang kings was identified, their dates and information about Shang culture remained unclear until the arrival of Tung Tso-pin (1895-1963). Between 1928 and 1937, the era of scientific excavation of oracle bones began. Academia Sinica's Institute of History and Philology carried out scientific archaeology at the Yin Ruins, unearthing thousands of pieces of shell and bone. Tung Tso-pin, specializing in oracle bone inscriptions, personally presided over the excavations. Studying the finds extensively, he established dating criteria for oracle bones in 1933. His "Yin li p'u" (Yin Calendar Table) remains a great contribution to the field. \=/

“In 1933, the scholar Kuo Mo-jo (1892-1978) published "Pu-ts'u t'ung tsuan" (Compilation of Oracle Bone Inscriptions), the first book to bring together all the data relating to oracle bones. He later went on to apply the information in oracle bone inscriptions to aspects of feudal society in ancient China. These last four scholars strengthened and built up the foundations for the academic study of oracle bones. Later students have taken the field to even greater heights through the efforts of earlier scholars. Current information is the result of continued excavation and research, which continuously replenishes our understanding of Shang history.” \=/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Oracle Bones: Brooklyn College and United College Hong Kong; Making an oracle bone, British Museum;

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated November 2016