TERRA COTTA ARMY OF EMPEROR QIN

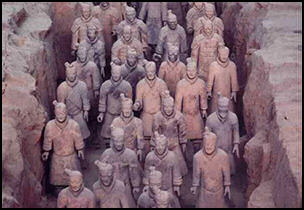

The terra-cotta Army of Emperor Qin consists of 10,000 or so life-size figures found in three massive pits with ramps used for putting the soldiers in their places. Most of the figures are armed warriors, meant to accompany to Emperor Qin to the after-life and protect him in heaven from his enemies. When it was unearthed by a man digging a well in 1974 in rural China, the Terracotta Army took the world by storm to become one of the greatest archaeological finds of all time.

The terra-cotta Army of Emperor Qin consists of 10,000 or so life-size figures found in three massive pits with ramps used for putting the soldiers in their places. Most of the figures are armed warriors, meant to accompany to Emperor Qin to the after-life and protect him in heaven from his enemies. When it was unearthed by a man digging a well in 1974 in rural China, the Terracotta Army took the world by storm to become one of the greatest archaeological finds of all time.

Produced during the third century B.C., this army of life-size figures is found in three massive pits with ramps used for putting the soldiers in their places. Most of the figures are armed warriors, meant to accompany to Emperor Qin Shihuang Di to the after-life and protect him in heaven from his enemies. Jeffrey Rigel of the University of California at Berkeley called the statues "a creation of awesome scale and accomplishment — an unforgettable symbol of the power of China's first emperor."

The Chinese believe that a person takes to heaven whatever he is buried with. Emperor Qin no doubt made many enemies in his long, ruthless career. He may have been worried that these enemies might gang up against him in the afterlife, which explains why he wanted to have such a large force to protect him.

Much of the work on the terra cotta army was done while Emperor Qin was still alive. In 206 B.C., four years after his death, the burial vaults containing the terra-cotta soldiers were burned and vandalized by peasants, who stole the real crossbows, spears, arrows and pikes carried by the statues and used them in a rebellion against Emperor Qin's descendants.

In 2019, Archaeology magazine reported: One of the most remarkable aspects of the Terracotta Army is the pristine state of the soldiers’ bronze weapons after 2,000 years underground. Because trace amounts of chromium have been detected on the blades, scientists have long presumed that ancient Chinese craftsmen invented a type of anti-rust coating. However, researchers have learned that the chromium is actually contamination from lacquer applied to the weapons’ handles and shafts, and is not responsible for the metal’s preservation. It is now thought that the chemical composition of the surrounding soil helped prevent corrosion. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July-August 2019]

See Separate Article TOMB AND PALACE OF EMPEROR QIN SHIHUANG factsanddetails.com

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ZHOU, QIN AND HAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221 B.C.): UPHEAVAL, CONFUCIUS AND THE AGE OF PHILOSOPHERS factsanddetails.com; POLITICS, REFORMS AND ALLIANCE-BUILDING DURING WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; QIN DYNASTY (221-206 B.C.) AND THE RISE AND FALL OF THE QIN STATE factsanddetails.com; EMPEROR QIN SHIHUANG: HIS LIFE AND THE PLOT TO ASSASSINATE HIM factsanddetails.com; EMPEROR QIN SHIHUANG AS THE LEADER OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; EMPEROR QIN SHIHUANG’s RULE (221-206 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; LAWS OF QIN factsanddetails.com; GREAT WALL OF CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; XIAN factsanddetails.com/china

Websites and Sources: Qin Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Emperor Qin Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Xian : Wikipedia Wikipedia

Terra-cotta Army of Emperor Qin Wikipedia Wikipedia ; UNESCO World Heritage Site : UNESCO ; Emperor Qin's Tomb: UNESCO World Heritage Site UNESCO ; Early Chinese History: 1) Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; 2) Chinese Text Project ctext.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han (History of Imperial China)” by Mark Edward Lewis and Timothy Brook Amazon.com; “Age of Empires: Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties” by Zhixin Sun, I-tien Hsing Amazon.com; “Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Dynasty” by Qian Sima and Burton Watson Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD 220" Amazon.com; “The First Emperor of China” by Jonathan Clements Amazon.com; “The Underground Terracotta Army of Emperor Qin Shi Huang” by Fu Tianchou Amazon.com; “The Eternal Army: The Terracotta Soldiers of the First Emperor” by Araldo De Luca and Roberto Ciarla Amazon.com; “Terracotta Army: Legacy of the First Emperor of China” by Li Jian, Hou-Mei Sung, Zhang Weixing ( Amazon.com ; Film: "The First Emperor" (also known as "The Emperor and the Assassin") by Chen Kaige Amazon.com

Visiting the Terra-cotta Army of Emperor Qin

Terra-cotta Army of Emperor Qin (in Qinling Town, 37 kilometers northeast of Xian, 7 kilometers east of Lintong County, 1.5 kilometers from Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum) is one of the most famous and impressive sights in China. The Terracotta Army is a collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of the China's first emperor, Qin Shi Huang. One of many treasures and objects buried with the emperor to accompany him in his afterlife, it is one of the most significant archeological excavations of the 20th century. About 2 million people check out the terra cotta army every year. It has been said that Qin's Tomb is "the only tomb one can compare in scale to the Pyramids."

Ligaya Mishan wrote in the New York Times: “Restorations here are still underway, although enough statues have been put back together to draw daily throngs, a living legion to face off with the dead. I steel myself for a nationalistic display of raw power, an overwhelming assembly poised to conquer. Instead, I feel a strange lightness, hemmed in by the crowd, gazing down into the great ashen pit. History belongs to the powerful, not those who serve them, but here the emperor is absent. How individual the soldiers are, six feet tall and dressed forever for battle, hair braided and wrapped in a tight bun tilted to the right or flattened beneath a cap or plated crown. I didn’t know we’d be so close that I could look them in the eye. Only from a distance are they an army; this near, each has a face entirely his own. Some seem caught midstride, cast down in thought, with a trace of a smile. Others brood and glower, or lie in parts on wheeled steel tables, as if in a makeshift hospital. They are beautiful, these broken sentinels, still half animated by the flesh-and-blood warriors who were their models, and by the invisible artisans who carved each knuckle, each puckered sleeve. Unmoored from their mission, they wait. Among them stand conscripts from minority peoples who were vanquished and swallowed up by empire. Their eyes and cheekbones are evidence: We, too, were here.” [Source: Ligaya Mishan, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

Website: Web Site: Wikipedia Wikipedia UNESCO World Heritage Site site: : UNESCO Admission: 110 yuan (includes Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum, Museum of Qin Terracotta Army, Museum of Terracotta Acrobatics, Museum of Terracotta Civil Officials and Museum of Stone Armor) Hours Open: 8:30am to 5:30pm (March 16 to November14); 8:30am to 5:00pm (November14 to March 15), Tel:+86 29 81399170; Website: Old Official Site www.bmy.com.cn Getting There: Tourism Bus 5 (306) from the east square of Xian Railway Station to Bing Ma Yong

Terra-Cotta Soldiers

The terra-cotta soldiers are amazingly life-like and detailed. Each one has an individual face, and its own hairstyle and facial expressions. Some look savage; some look serene and composed; others look bold and self-assured; a few look like they are about ready to crack a smile. A name, possibly from artist or maybe from soldier, is stamped on the neck of every soldier. Some scholars believe each one is a facsimile of a real soldier in Qin's army.

The heads and hands were cast in molds and added to the bodies after they were fired. The clothing and armor details were also added later by a craftsman, who also added a half inch of clay to heads, which was reworked to give their faces and hairstyles individual characteristics. Typical warriors including general figures, Bttele-robbed warriors, armoured warrior, standing archers and kneeling archers as well as saddled horses. Most warriors hold weapons on their hands, such as bows, spears, swords and machetes.

stone helmet and armor of terracotta soldiers

From what scholars can ascertain the hollow bodies and arms of the soldiers were most likely made from loops of clay pressed together with a paddle (fingerprints and paddle marks have been found on the soldiers). The figures were dried with a low-heat fire in a kiln. Coal was then added to raise the temperatures to 1800̊F. The statues baked for several days until they turn red. About 10 percent of soldiers produced in modern workshop fail because of the difficulty in controlling the temperature. After they cool, successfully-made statues produce a metallic sound when tapped. Defective ones produce a hollow thud.

The faces were made in one of a dozen molds. Details such as ears, hairdos, eyebrows, mustaches and beards were added by the sculptors. The bodies were created separately. Hairstyles and headgear reflected rank with the most elaborate generally belonging to the higher ranks. Soldiers wore simple caps over hair tied into a topknot. Officers wore caps crowned by ornamental designs.

The heads and hands were cast in molds and added to the bodies after they were fired. The clothing and armor details were also added later by craftsmen, who also added a half inch of clay to the heads, which were reworked to give their faces and hairstyles their individual character. The soldiers were then painted. Only a few of the figures contain original pigments, which were made from minerals mixed with a binders such as egg whites or animal blood. Most have lost their colors to erosion, water and time.

In addition to soldiers there are stern-looking terra cotta bureaucrats to run the administration as well as acrobats and musicians to entertain the Emperor in the afterlife. Terra cotta was most likely chosen for the afterlife because flesh and wood rots. Earlier rulers had their servants, concubines and soldiers — not clay copies of them — buried alive with them.

Ranks of Terra-Cotta Soldiers

In the general area of the pits with the terra-cotta soldiers and the tomb, archaeologists have found the remains of a palace, secondary pits containing horse stables, bronze chariots, a cemetery for prison laborers who built the mausoleum, the skeletons of horses and exotic animals, and seven human skeletons that may be Emperor Qin’s children.

Most of the figures represent ground troops—soldiers and archers. About for dozen are charioteers and officers of varying ranks. Most face east, the direction from which the imperial capital was most vulnerable to attack. The figures were aligned in battle formation with warriors in the front and side rows carrying a range of weapons, including crossbows and lances. Behind them are officers with short range weapons such as swords and charioteers with bows and arrows. Although the soldiers were recreations the weapons, in many cases, were real bronze ones. Hundreds of blades and crossbow triggers have been found, along with more than 40,000 arrowheads.

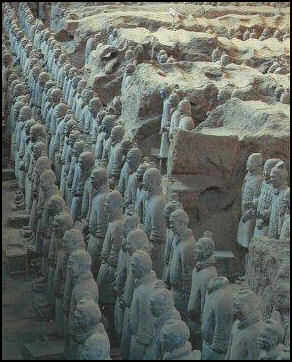

Pit 1 is filled with over 40 war chariots and 6,000 life-size warriors organized in rank. The terra-cotta figures, mostly infantrymen, are organized into 300-meter-long rows, the same way that Emperor Qin's honor guard used to line up before they set off on a military campaign. There are five rows of warriors (standing four abreast) and six rows of chariots, each pulled by four horses and accompanied by 15 soldiers. Among the soldiers are two "generals." The figures are 5½ to 6 feet tall. Officers are always taller than ordinary soldiers.

The soldiers weigh around 330 pounds. Most of them originally carried swords, spears and crossbows. The terra-cotta horses are magnificent creatures: strong yet graceful. They look alert and ready to do battle. Their ears are propped forward, their tails are short and knotted and their jawlines are bold and powerful. They are slightly less than six feet tall, 7 feet long and weigh 440 pounds. Gold, jade, bamboo and bone artifacts, linen, silk, pottery utensils, bronze objects, swords and iron farm tools were unearthed beside the warriors and chariots.

Pit 2 contains 900 terra-cotta figures, including archers, cavalry troops, charioteers, infantrymen, 356 chariot horses, 116 saddled horses, and 89 war chariots. The terra-cotta figures are arranged in the L-shaped pit like real soldiers in a real battle. In the forward position are standing and kneeling archers. Behind them are calvary units and charioteers and infantry organized in four abreast units. Reserve chariots are off to one side. Among the soldiers are two "generals."

The space where the warriors were housed was comprised of a black tile floor and a ceiling made of tightly-placed, log-like wooden beams. Wood posts supported the beams. Walls were made of rammed earth. On top of the beams were fiber mats, clay and earth fill. After Pit 1 was looted the ceiling and the layers of clay and earth above it crashed on to the warriors, shattering them all.

Unearthed with the terra-cotta soldiers are two large painted bronze chariots. Weighing 2,200 pounds each, the chariots each have two wheels, four horses and a driver. They are made completely of bronze and are about half the size of real chariots. Produced to carry the dead to the afterlife, the chariots were made using a number of advanced technologies: casting welding, riveting, casing, chain-making, fastener-making and metal painting.

Colors of Emperor’s Qin’s Terra-Cotta Warriors

with original pigments

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “The monochrome figures that visitors to Xian’s terra-cotta army museum see today actually began as the multicolored fantasy...Qin’s army of clay soldiers and horses was not a somber procession but a supernatural display swathed in a riot of bold colors: red and green, purple and yellow. [Source: Brook Larmer. National Geographic, June 2012 *]

Various materials including precious stones were ground into powder that provided pigment for the egg-based paint that was applied over two layers of lacquer. The materials and colors included cinnabar for red, charcoal for black, cinnabar and barium copper silicate for purple, azurite for blue, iron oxide for dark red, crushed bones burned at high temperatures for white and malachite for green. Brown, back and the ground layer were made of the sap of a local tree. *\

When archeologist began uncovering the army, the lacquer had dried and flaked off, taking the color with it. Today, scientists using a variety of techniques have figured out what the ancient hues were and in some cases where they went on the warriors so that the original colors of entire soldiers could be determined. *\

Larmer wrote: “Sadly, most of the colors did not survive the crucible of time—or the exposure to air that comes with discovery and excavation. In earlier digs, archaeologists often watched helplessly as the warriors’ colors disintegrated in the dry Xian air. One study showed that once exposed, the lacquer underneath the paint begins to curl after 15 seconds and flake off in just four minutes—vibrant pieces of history lost in the time it takes to boil an egg. Now a combination of serendipity and new preservation techniques is revealing the terra-cotta army’s true colors. A three-year excavation in Xian’s most famous site, known as Pit 1, has yielded more than a hundred soldiers, some still adorned with painted features, including black hair, pink faces, and black or brown eyes. The best-preserved specimens were found at the bottom of the pit, where a layer of mud created by flooding acted as a sort of 2,000-year-long spa treatment.” *\

Were the Terracotta Warriors Based on Real People? Check the Ears and 3-D Images

to help answer the question were the terracotta warriors based on actual people archaeologists are looking at variations in the soldiers’ ears. Elizabeth Quill wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Andrew Bevan, an archaeologist at University College London, along with colleagues, used advanced computer analyses to compare 30 warrior ears photographed at the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor in China to find out whether, statistically speaking, the auricular ridges are as “idiosyncratic” and “strongly individual” as they are in people. Turns out no two ears are alike — raising the possibility that the figures are based on a real army of warriors. Knowing for sure will take time: There are over 13,000 ears to go. [Source: Elizabeth Quill, Smithsonian magazine, March 2015]

With a rounded top and a rounded lobe, one ear is among the most pleasing to the eye. The rib that runs up the center of the outer ear, called the antihelix, forks into two distinct prongs, framing a depression called the triangular fossa. Among the odder in shape, another ear has a surprisingly squared lobe, a heavy top fold (known as the helix), no discernible triangular fossa and a more pronounced tragus (that flat protrusion of cartilage that protects the ear canal). A third ear belongs to a warrior with the inscription “Xian Yue.” “Yue” likely refers to the artisan who oversaw its production, presumably from Xianyang, the capital city. Researchers haven’t yet found any correlation between ear shape and artisan.

In 2014, scientists announced they had discovered the first evidence which they say could prove that each of the clay figures in the army is modelled on an individual, real soldier. [Source: Adam Withnall wrote in The Independent, “Despite the soldiers’ varying facial expressions and hairstyles, it has been speculated that such a large clay installation would have required an almost factory-like system of production, churning out lines of standard ears, noses, mouths and so on that were then assembled into full soldiers. Exploring the precise detail of the clay soldiers has proved incredibly challenging over the years – the site is more or less completely closed off due to the army’s fragile nature. The soldiers are packed so tightly together that it is impossible to move between them without risking damage. [Source: Adam Withnall, The Independent, November 20, 2014 ^^^]

"But using the latest 3D imaging technology, a team of archaeologists from University College London (UCL) and from Emperor Qin Shi Huang's Mausoleum Site Museum in Lintong, China, have been able to digitally recreated soldiers from the army for further study. According to a National Geographic report, the team was able to accurately map the ears of a sample of 30 soldiers from a safe distance and then study their geometries back in the lab. UCL’s Andrew Bevan explained that human ears are so distinct they can be “as effective as a fingerprint”. If the army truly represented real people, their ears would be unique. Sure enough, not only were no two ears in the group exactly the same – but they differed to the same extent as would be expected in a human population. ^^^

Archaeologist Marcos Martinón-Torres told National Geographic: “Based on this initial sample, the terra-cotta army looks like a series of portraits of real warriors.” The initial results support previous suggestions that the army was in fact produced in a large series of workshops rather than assembly lines. The study will now be opened up to a wider sample size to confirm the findings. ^^^

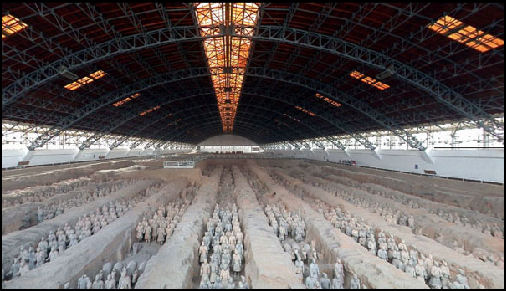

Museum of Terra Cotta Warriors and Horses of Qin Shihuang

Museum of Terra Cotta Warriors and Horses of Qin Shihuang consists of three pits sheltered in massive warehouse-like buildings as well as the hall of the two bronze chariots and horses. Covering an area of 22,780 square meters, the three pits contain a total of 8,000 clay soldiers and horses. Over 10,000 bronze weapons were discovered in the three pits. The figures can not be photographed. About 1.5 kilometers away is the 250-foot-high earthen mound that covers Emperor Qin's tomb.

The Terracotta Army, also called the "Terra Cotta Warriors and Horses", is a collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang (the first Emperor of China). Farmers discovered the statues of the soldiers in 1974. The Museum of the Terracotta Army was built on the site where the Terracotta Army was found and opened to the public in 1979. The construction of the army began in 246 B.C. and came to an end in 208 B.C.

The museum of Qin Shihuang Terracotta Warriors and Horses has six exhibitions: Pit No.1, Pit No.2, Pit No.3, Exhibition of Bronze Chariots and Horses, Exhibition of Cultural Relics from Qin Shihuang Mausoleum and Exhibition of Precious Cultural Relics from Qin Shihuang Mausoleum. Arguably the two most interesting things in the museum besides the terra-coot soldiers are two large painted bronze chariots. Weighing 2,200 each and discovered in November 1980 in a pit 20 meters from Emperor Qin's tomb, the chariots each have two wheels, four horses and a driver. The chariots are made completely of bronze and are about half the size of a real chariot. Produced to carry the dead to the afterlife, the chariots were made using a number of advanced technologies: casting. welding, riveting, casing, chain-making, fastener-making and metal painting. [Source: Louis Mazzatenta, National Geographic, October 1997]

The museum is an integration of research, display, and education. Only about a third of Pit 1, part of Pit 2, and Pit 3 have been excavated. In the general area of the pits and the tomb, archaeologists have found the remains of a palace, secondary pits containing horse stables, bronze chariots, a cemetery for prison laborers who built the mausoleum, the skeletons of horses and exotic animals, and seven human skeletons that may have been Emperor Qin's children.

Pit 3 is shaped like a Chinese character and contains only 68 terra cotta soldiers, a colorfully-painted war chariot and 30 bronze weapons. It is housed in a building that covers 520 square meters. Some scholars have speculated that maybe it was a command post because the warriors in this pit are arranged face to face. Discovered in May 1976, Pit 3 has only recently been excavated and opened to the public. It contains a few painted terra-cotta soldiers. Pit 4 is empty, perhaps because a rebel uprising prevented it from being completed. It was also discovered in 1977.

Travel Information: 1). The museum has excellent services, providing wheel chairs for the people with disabilities, lounges for tourists, first aid services and tours in Chinese, English and Japanese. 2). One can bargain in the museum shops just like street vendors. Tel: + 86-29-81399001 +86-029-81399170 (complaint line); 120 (for first aid); +86-029-81399170 (inquiries); Hours Open: 8:30am-5:30pm (from March 16-November 14); 8:30am-5:00pm (from November 15-March 15); Admission: 90 yuan (high season); 65 yuan (low season); Getting There: By Bus from Xian: You can take the green Terracota Warrior minibuses at the train station or bus No. 306, 914, 915, 101. All cost 7 yuan and the ride takes about an hour;

Pit 1 at the Museum of Terra Cotta Warriors

Pit 1 is filled with 40 terra-cotta war chariots and 6,000 life-size, terra-cotta warriors organized in rank in a 10,000-square-meter, hanger-like building. To give you a sense of how many figures are here: take three football fields and cover every inch with players.

Most of the figures represent ground troops — soldiers and archers. About for dozen are charioteers and officers of varying ranks. Most face east, the direction from which the imperial capital was most vulnerable to attack. The infantrymen are organized into 300 meter-long rows, the same way that Emperor Qin's honor guard used to line up before they set off on a military campaign. There are five rows of warriors (standing four abreast) and six rows of chariots, each pulled by four horses and accompanied by 15 soldiers. Among the soldiers are two "generals." The figures are 5½ to 6 feet tall and weigh about 150 kilograms. Officers are always taller than ordinary soldiers.

The figures were aligned in battle formation with warriors in the front and side rows carrying a range of weapons, including crossbows and lances. Behind them are officers with short range weapons such as swords and charioteers with bows and arrows. Although the soldiers were recreations the weapons, in many cases, were real bronze ones. Hundreds of blades and crossbow triggers have been found, along with more than 40,000 arrowheads. [Source: National Geographic]

The space where the warriors were housed was comprised of a black tile floor and a ceiling made of tightly-placed, log-like wooden beams. Wood posts supported the beams. Walls were made of rammed earth. On top of the beams were fiber mats, clay and earth fill. After Pit 1 was looted the ceiling and the layers of clay and earth above it crashed on to the warriors, shattering them all.

About one thousand figures have been restored to their standing position. Most of them originally carried swords, spears and crossbows. Visitors can walk completely around the area where the restored soldiers are found. Most of the terra-cotta soldiers in Pit 1 were toppled over and cracked when the roof of the vault collapsed. They are currently being put back together humpty-dumpty fashion in a part of the pit, largely off limits to visitors.

Most of horses were also damaged. The ones that survived are magnificent creatures: strong yet graceful. They look alert and ready to do battle. Their ears are propped forward, their tails are short are knotted and the jawlines are bold and powerful. They are slightly less than six feet tall, 7 feet long and weigh 200 kilograms. Gold, jade, bamboo and bone artifacts, linen, silk, pottery utensils, bronze objects, swords and iron farm tools were unearthed beside the warriors and chariots. The well-preserved swords were treated with a preservative and were made a copper and tin alloy with 13 other elements including nickel, cobalt and magnesium.

Pit 2 at the Museum of Terra Cotta Warriors

Pit 2 is housed in a 6,000-square-meter exhibit hall made with four different colors of Fujian marble. It contains 1300 mostly -broken teera-cotta warriors of different kinds, including archers, cavalry troops, charioteers, infantrymen, 356 chariot horses, 116 saddled horses, and 89 war chariots. This army was once sheltered by a 7,000 square-meter roof that collapsed, possibly the result of a fire caused by the rebellion after the emperor's death (remnants of charred timbers are clearly visible).

Pit No. 2 is L-shaped, and is formed into four sections: 1) the eastern part, with 172 archers in kneeling position along the corridors in the middle; 2) the southern part, formed by eight corridors in each row followed by two to four chariot soldiers (No infantrymen are found here); 3) the central part in which three rows of chariots, placed in three corridors, six chariots in each row, each followed by infantry soldiers and cavalrymen, forming a battle formation of chariots, infantrymen and cavalrymen; and 4) the L-shaped northern part. In its three corridors, there are two battle chariots placed in the east, followed by eight teams of cavalrymen, each team being arranged in four rows. These four sections are both independent of one another and connected with each other. Different kinds of soldiers are combined to form one integrated battle formation. which can also be described as an independent formation composed of four smaller ones.

The terra-cotta figures are arranged in the L-shaped pit like real soldiers in a real battle. In the forward position are standing and kneeling archers. Behind them are calvary units and charioteers and infantry organized in four abreast units. Reserve chariots are off to one side. Among the soldiers are two "generals." Unlike the intact ranks of figures on view in Pit 1, most of the figures in Pit 2 are broken into pieces. Most were damaged by the collapse of the roof. Kneeling archers fared better than standing soldiers because their compact position helped them absorb the shock of the collapse. What is interesting about Pit 2 is that visitors can watch the excavation work. The archaeologists and their assistants work under bright lights as if they were actors, extras and crew on a movie set.

Pit 2 was discovered in April, 1976 but excavation work didn't begin until March 1994. The first phase of the excavation, completed in 1997, involved exposing the collapsed roof. The second phase, which is being done now, involves unearthing of the buried soldiers and horses.

Bronze Chariots and Horses

Bronze chariots and horses were found 20 meters west of QinShihuang's burial mound. In 1980, two large size bronze chariots with horses, situated side by side, were unearthed from a wooden container. After years of work, they have were restored to their original shape and position. The chariots and horses are half life-size, but a full imitation of the real thing. It is believed that Emperor Qin Shihuang used similar chariots when making his inspection tours.

Chariot No. 1 has two wheels, a single shaft and a team of four horses. The chariots chamber is rectangular in shape, 126 centimeters wide and 70 centimeters deep. The chariot chamber is protected by three boards, one at each side and one in the front. There is a door at the back of the chariot to allow one to get in or out of the carriage. A shield is placed inside the right chamber board. Inside the front board is a crossbow and a quiver. A round canopy supported with a single bronze stem stands on the chariot, with a charioteer, 91 centimeters in height, standing under the canopy. Chariot No.1 was named "Escort Chariot", or "Battle Chariot", or "Height Chariot". People could stand in it when driving or riding in it.

Chariot No. 2, also drawn by four horses, was called Chariot of Tranquility because it was more sumptuous and presumably more comfortable to ride in during trip. The chariots is 3.17 meters in length and 1.062 meters high. It has an oval plate as its roof. The chariot body is divided into two chambers. The one in the front is for the charioteer, driving in a kneeling position. The back chamber is for the host of the chariot. The chariot chambers are richly decorated with dragon, phoenix and flowing cloud patterns.

The main body of the chariots and the horses were cast with bronze and many parts and ornaments were made of gold or silver. After all the separate parts were cast or made, they were joined together through casting, welding, gluing, riveting, buttoning and chaining. These two chariots were painted with rich colors. The horses were painted white. All the colors used were from mineral pigments. The thickness of the glue was carefully adjusted and controlled to create a three dimensional effect.

Mini Terracotta Soldiers

The Terracotta Army of Qi Huang Shi is the only known example of an army of life-size ceramic soldiers in China. Some of the Han dynasty rulers built pits with armies of terra cotta soldiers for their burials, but the soldiers were considerably smaller. The soldiers in the Terra Cotta Army of Han Jing Di were only about 60 centimeters (two feet) tall. Those that belong to the terra cotta army of the Qi state ruler described below were between 22 and 31 centimeters (9 and 12 inches).

In 2018, Live Science reported on a miniature terra cotta army found in Linzi. Linzi, originally called Yingqiu, was the capital of the ancient Chinese state of Qi during the Zhou Dynasty. The ruins of the city lie in modern-day Linzi District, Shandong, China. The city was one of the largest and richest in China during the Spring and Autumn Period. Based on the design of the newfound artifacts, archaeologists believe that the pit was created about 2,100 years ago, or about a century after the construction of the Terracotta Army. [Source:Owen Jarus, Live Science, November 13, 2018]

Owen Jarus of Live Science wrote: “The southern part of the pit is filled with formations of cavalry and chariots, along with models of watchtowers that stand 55 inches (140 centimeters) high. At the pit's center, about 300 infantrymen stand alert in a square formation, while the northern part of the pit has a model of a theatrical pavilion holding small sculptures of musicians. "The form and scale of the pit suggest that it accompanies a large burial site," wrote archaeologists in a paper published recently in the journal Chinese Cultural Relics. The "vehicles, cavalry and infantry in square formation were reserved for burials of the monarchs or meritorious officials or princes," the archaeologists wrote.

“Based on the date, size and location of the pit, archaeologists believe that this newly discovered army may have been built for Liu Hong, a prince of Qi (a part of China), who was the son of Emperor Wu (reign 141–87 B.C.). “Hong was based in Linzi, a Chinese city near the newly discovered pit; he died in 110 B.C. "Textual sources record that Liu Hong was installed as the prince of Qi when he was quite young, and he unfortunately died early, without any heir," archaeologists wrote in the journal article. Shortly before Hong's death, according to writings by ancient historian Ban Gu, a comet appeared in the sky over China.

For information on Han Jing Di's Pint-Size Terra Cotta Army See HAN DYNASTY RULERS factsanddetails.com

Terracotta Army Museum Archeology

Lu Hongyan and Zhao Xu wrote in the China Daily: “The museum has restored and displayed about 1,200 of the estimated 6,000 warriors in Pit 1. The soldiers stand on well-baked pottery bricks sturdy enough to sustain the figures, which weigh an average of 200 kilos each. A wooden ceiling that once sheltered the warriors rotted away hundreds of years ago, along with the large beams that supported it and the rammed earth that was laid on top. "All the wooden sections have been reduced to dust. by the grind of time, " Pan Ying, 28, a museum guide, told the China Daily, pointing to impressions left in the earth by the wheels of long-gone wooden chariots, and the undulating earth that avalanched into the pit when the rafters gave way, completely covering many of the terracotta figures. [Source:Lu Hongyan and Zhao Xu, China Daily, October 31, 2014]

archer head

“"The construction of the giant roof, which today houses the entire Pit 1, was undertaken between 1976 and 1979, the year the museum officially opened to the public, “"If the completion of the Terracotta Army although, some say it was never completed, can be seen as the beginning of the end for the empire, then its discovery was indeed the end of the beginning for us," says Xia Yin, a conservationist with the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum Museum. "What our ancestors spent three decades building will take us forever to decipher."

“Today the scene is nothing like it was in the first few years of research that followed that 1974 spring. "One discovery led to another. We felt both thrilled and ill prepared," says Yuan Zhongyi, the leader of the site's first archaeological team, comprising 10 members, who is known as "the father of the Terracotta Warriors", the 82-year-old recalled. "Before the roof, we lived on the site in tents and conducted our excavation work in the open. I remember being woken at midnight by lashing rain, and running outside and calling out to everybody. Using plastic sheets and straw mats, we launched a desperate attempt to rescue our silent friends.

Queen Elizabeth of the United Kingdom visited the terracotta army in October 1986. She wore an apple-green suit and matching gloves. Jimmy Carter came twice; in 1981 shortly after he was U.S. president, and again in 2014 when he was 89. Bill Clinton, when he was U.S. president, was one of the few non-archeologists he has been allowed to climb into the pit with the soldiers. Henry Kissinger, former US Secretary of State and a key player in Sino-US relations for four decades, was also allowed to do so. Since 1979, he was visited five times, the last time in last time he came, in June 2013 with his wife, daughter-in-law, and two grandchildren. A curator at the museum said, "When we offered him the chance to go into the pit, he was absolutely thrilled, and asked earnestly: "Can my family come with me?' A group of visually impaired people at the museum were allowed to 'feel' the warriors, Former French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac said: "One can't claim to have visited China unless one has seen these Terracotta Warriors."

Preserving the Colors of the Terracotta Soldiers

Zhou Tie, the museum's lead conservationist, told the China Daily: "If you can believe it, the monochrome army we see today was swathed in vibrant hues when the soldiers were first born. Colors extracted mostly from natural materials, including semiprecious stones and animal bones, were applied over a layer of lacquer that coated the pottery figures." [Source: Lu Hongyan and Zhao Xu, China Daily, October 31, 2014]

Lu and Zhao wrote: “Many of the colors were lost, either in a suspected arson attack by peasant forces at the empire's demise, or during the army's 2,000-year subterranean sojourn. The sections that survived fire and age were probably ruined by Xian's arid atmosphere when they were uncovered during the excavation. "When fully exposed to dry air, the lacquer begins to curl after about 15 seconds and flakes off in about four minutes, permanently taking the precious traces of crimson, purple and white with it," Zhou says. "Between the early 1980s and the mid-90s, we tried everything we could to retain the moisture inside the lacquer layer and stabilize it, but in vain."

“The breakthrough came around 1995 when the team decided to experiment with a material used in the preservation of ancient lacquer furniture. "It's a zillion times more complicated than it sounds," Zhou says, adding that the many failures on the road to success had been an emotional roller coaster. "'Breakthrough' may not be the right word. In research and protection, we only move forward by an inch a day," the 56-year-old says.

“Some of the newly restored warriors will be on show at the museum as part of an exhibition called Terracotta Warriors: True Colors. In a sparsely decorated, dimly lit hall, the faint colors, be it a blush on the cheek or a swirl on a hemline, are illuminated by spotlights, and they tell a long-forgotten story. The face of one figure, believed to represent an army sorcerer, bears a distinct green tint. It is a place where history can echo in a child's imagination.”

Discovery of the Terracotta Army

colored soldiers

Archaeologists were stunned when the terra-cotta soldiers were discovered in the spring of 1974. Unlike Emperor Qin's tomb there was no written records of the terra-cotta army. When archaeologists arrived, they discovered some terra-cotta heads in the home of an old woman who had placed the heads on an altar and worshiped them as gods. The archaeologists had no idea either of the magnitude of what had been discovered. They expected only to stay for a few weeks. More than 40 years later, they still here uncovering new stuff.

Two men in Xian claim to be the first man to unearth the terra-cotta man. Yang Quanyi, works at a tourist shop with a sign "The Man Who Discovered the Terra-Cotta Warriors," and maintains he was discovered even though he offers few details. Yang Zhifa says he was part of a crew digging a well during a drought. After digging six feet into the ground, he said, he hit sometime hard. "At first I thought I had hit a brick," he told the New York Times. "But when I scraped away the dirt, it was the length of a full body." Today, According to the China Daily, the hoe he used that day is framed and hanging proudly on the wall of his sitting room.

For Sun Shengan, the hundreds of life-size terra-cotta warriors are impressive, but sad. “Look carefully at their faces, and you will see each is different,” Mr. Sun, a former government employee now working as a private guide, told the New York Times “not a single one looks happy. Perhaps because they were too oppressed,” nodding meaningfully. [Source: Didi Kirsten Tatlow, New York Times, December 28, 2011]

Most of the terracotta figures and chariots were found broken, their once-vibrant colors scorched, washed away or muted by time. Excavation continues and to date, over 1,000 figures have been reassembled, now protected by overhead, warehouse-like structures.

See Separate Article ARCHEOLOGY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Terra Cotta Army, Ohio State University; 7) Terra cotta soldiers, Louis Perrochon

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021