EMPEROR QIN SHI HUANG

One rendering of Emperor Qin Shihuang Emperor Qin Shi Huang (Qin Shihuang,ruled 221–210 B.C.) is arguably the greatest leader in Chinese history. Sometimes called the "Chinese Caesar," he unified China, founded the Qin Dynasty, gave China its name (in China Qin is pronounced as Chin as well as Qin), built large sections of the Great Wall of China, and was China's first bonafide emperor. He was buried in the world's largest tomb in Xian not far from the famous terra cotta army that was created to honor him and protect him in the afterlife. Qin Shi Huang real name was Ying Zheng. In China, he has always called the First Emperor (Qin Shi Huang) in histories.

Qin was a military adventurer who unified China by conquering and subsuming the six warring states. His achievements came at great human costs though. He imposed absolute order by executing anyone suspected of disloyalty. Thousands were killed in his military campaigns, in his attacks against intellectuals, and among the labor gangs that built the Great Wall and other structures. But in doing all this he brought China together."We wouldn't have a China without Qin Shi Huang," Harvard University's Peter Bol told the BBC. "I think it's that simple."

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: The judgments passed on him vary greatly.: the official Chinese historiography rejects him entirely—naturally, for he tried to exterminate Confucianism, while every later historian was himself a Confucian. Western scholars often treat him as one of the greatest men in world history. Closer research has shown that Qin Shi Huang was evidently an average man without any great gifts, that he was superstitious, and shared the tendency of his time to mystical and shamanistic notions. His own opinion was that he was the first of a series of ten thousand emperors of his dynasty (Qin Shi Huang means "First Emperor"), and this merely suggests megalomania.” [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Ying Zheng was 38 years old when he declared himself Emperor. Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “It is difficult to find any parallel in history. He was not a conquering general like King Wu of the Zhou, Alexander in Greece, or Caesar in Rome. There is no hint that as king of the pre-conquest state of Qin Ying Zheng ever ventured into the field of battle to establish his abilities as a leader of men.As a child, his father had been no more than an insignificant junior son with no expectation of succeeding to the throne of Qin. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ZHOU, QIN AND HAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221 B.C.): UPHEAVAL, CONFUCIUS AND THE AGE OF PHILOSOPHERS factsanddetails.com; POLITICS, REFORMS AND ALLIANCE-BUILDING DURING WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; QIN DYNASTY (221-206 B.C.) AND THE RISE AND FALL OF THE QIN STATE factsanddetails.com; EMPEROR QIN SHI HUANG AS THE LEADER OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; EMPEROR QIN SHI HUANG’s RULE (221-206 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; LAWS OF QIN factsanddetails.com; TERRA COTTA ARMY AND TOMB OF EMPEROR QIN SHI HUANG factsanddetails.com; GREAT WALL OF CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; XIAN AND SHAANXI PROVINCE factsanddetails.com/china

Websites and Sources: Qin Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Emperor Qin Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Xian : Wikipedia Wikipedia

Terra-cotta Army of Emperor Qin Wikipedia Wikipedia ; UNESCO World Heritage Site : UNESCO ; Emperor Qin's Tomb: UNESCO World Heritage Site UNESCO ; Early Chinese History: 1) Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; 2) Chinese Text Project ctext.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han (History of Imperial China)” by Mark Edward Lewis and Timothy Brook Amazon.com; “Age of Empires: Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties” by Zhixin Sun, I-tien Hsing Amazon.com; “Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Dynasty” by Qian Sima and Burton Watson Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD 220" Amazon.com; “The First Emperor of China” by Jonathan Clements Amazon.com; “The Underground Terracotta Army of Emperor Qin Shi Huang” by Fu Tianchou Amazon.com; “The Eternal Army: The Terracotta Soldiers of the First Emperor” by Araldo De Luca and Roberto Ciarla Amazon.com; “Terracotta Army: Legacy of the First Emperor of China” by Li Jian, Hou-Mei Sung, Zhang Weixing ( Amazon.com ; Film: "The First Emperor" (also known as "The Emperor and the Assassin") by Chen Kaige Amazon.com

Emperor Qin Shi Huang and the Creation of China

According to the BBC: When Qin came to power China was a land of many states that had as much in common — in terms of climate, lifestyle and food — as northern Germany and southern Spain. Before Qin, China's multiple states were diverging, rather than converging, Bol told the BBC. "They have different calendars, their writing was starting to vary… the road widths were different, so the axle width is different in different places." [Source: Carrie Gracie, BBC News, October 15, 2012]

Shi Huangdi (First Emperor) took his title after he consolidated his power. The Emperor title was a formulation previously reserved for deities and the mythological sage-emperors. He imposed Qin’s centralized, nonhereditary bureaucratic system on his new empire. In subjugating the six other major states of Eastern Zhou, the Qin kings had relied heavily on Legalist scholar-advisers. Centralization, achieved by ruthless methods, was focused on standardizing legal codes and bureaucratic procedures, the forms of writing and coinage, and the pattern of thought and scholarship. To silence criticism of imperial rule, the kings banished or put to death many dissenting Confucian scholars and confiscated and burned their books. Qin aggrandizement was aided by frequent military expeditions pushing forward the frontiers in the north and south. *

Dr. Eno wrote: “The First Emperor wished to be the founder of dynasty that would last forever. The accomplishments of the Qin were...astonishing. Nevertheless, he has traditionally been regarded as a failure and his ambitions mocked as the grossest form of megalomania. It is true that the Qin Dynasty lasted a mere fifteen years and that the First Emperor himself completed the last of his many imperial tours as a decomposing corpse whose smell was camouflaged by cartloads of rotting fish. How much more astonishing, then, that in so brief a time the Qin managed to thoroughly transform the nature of the Chinese state and establish the structures that would organize and constrain political life in China until the end of the Imperial era in 1911. All this was accomplished before the First Emperor died in 210 B.C., at the age of forty-nine.” [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University ]

Emperor Qin’s Early Life

Another rendering of Emperor Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang was born Prince Ying Zheng in 270 B.C. and began his career as an empire builder at the age of 12 or 13 when he inherited the throne of Ch'in Qin, a small kingdom in what is now the Shaanxi region. His kingdom was known for its horsemen and occupied an area regarded as a wasteland inhabited by savages by Chinese further to the east. To remove possible threats to his throne Qin had his mother's lover executed, along with his entire clan. During the first 25 years of his reign he engaged in ruthless battles that led to the annexation of six kingdoms.

A hundred years after Qin’s death the famous historian Sima Qian said of the young king: "With his puffed-out chest like a hawk and voice of a jackal, Qin is a man of scant mercy who has the heart of a wolf. When he is in difficulty he readily humbles himself before others, but when he has got his way, then he thinks nothing of eating others alive. If the Qin should ever get his way with the world, then the whole world will end up his prisoner."

Dr. Eno wrote: “As a child, his father had been no more than an insignificant junior son with no expectation of succeeding to the throne of Qin. A series of strange events had changed all that, but not before the boy Ying Zheng had passed his childhood in the distant state of Zhao, where he had lived in hiding with his commoner mother at a time when his father was rising to power in Qin. Ying Zheng did not even enter the state he was to rule until five years before his accession to the throne. He had inherited the throne when still a boy and faced, during his earliest years, a most difficult type of challenge – his mother was disgraced in a wild sexual scandal and his prime minister and chief mentor, whom some reports claim as his secret father, was involved. Ying Zheng, among his early acts as a young king, was forced to banish his mother and his closest male senior companion and counselor. Now, quite suddenly, this lonely man found the world fall into his absolute power. He now ruled the entire civilized world, as he knew it. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“For those who are curious, the Qin annals record that the Ying clan was founded by the son of a grand-daughter of the Emperor Zhuanxu. It seems that she gave birth to him after a dark bird dropped an egg to her while she was weaving. She swallowed the egg, and the eventual result was the reunification of China. /+/

Merchant Lu Buwei and the Rise of Qin Shi Huang

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “A son of one of the concubines of the penultimate feudal ruler of Qin was living as a hostage in the neighboring state of Chao, in what is now northern Shanxi. There he made the acquaintance of an unusual man, the merchant Lu Buwei, a man of education and of great political influence. Lu Buwei persuaded the feudal ruler of Qin to declare this son his successor. He also sold a girl to the prince to be his wife, and the son of this marriage was to be the famous and notorious Qin Shi Huang. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Lu Buwei came with his protege to Qin, where he became his Prime Minister, and after the prince's death in 247 B.C. Lu Buwei became the regent for his young son Qin Shi Huang (then called Cheng). For the first time in Chinese history a merchant, a commoner, had reached one of the highest positions in the state. It is not known what sort of trade Lu Buwei had carried on, but probably he dealt in horses, the principal export of the state of Chao. As horses were an absolute necessity for the armies of that time, it is easy to imagine that a horse-dealer might gain great political influence.

“Soon after Qin Shi Huang's accession Lu Buwei was dismissed, and a new group of advisers, strong supporters of the Legalist school, came into power. These new men began an active policy of conquest instead of the peaceful course which Lu Buwei had pursued. One campaign followed another in the years from 230 to 222, until all the feudal states had been conquered, annexed, and brought under Qin Shi Huang's rule.

Emperor Qin’s Character

Emperor Qin statue

Dr. Eno wrote: “Chinese historical texts, for all their voluminous records, are among the world’s most barren when it comes to the personal character of rulers; how are we to imagine the psychological stresses that bore upon the conquering ruler of Qin as the Chinese world watched him take his place beside the demi-gods who had founded previous dynasties? No turning point in Chinese history was a more decisive pivot than 221 B.C. Yet, in many ways, none involved a more delicate balance of unstable political and personal factors. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“It is difficult to find significant information concerning the character of the First Emperor prior to the Qin conquest; his role in the politics of Qin is unclear, and there is little specifically pertaining to his personal conduct. This situation is dramatically reversed when we come to the years following the conquest, when, for a time, Ying Zheng, the first “emperor” of China, was by far the most powerful man on earth, overseeing a revolution of unprecedented scale and with an impact lasting to this day. Most of what we know of the First Emperor after the conquest reflects an increasing tendency towards self-aggrandizement, religious obsession, despotism, paranoia, and secrecy.” /+/

“It is possible to view the First Emperor as a passive beneficiary of the system within which he ruled, the talent of his ministers and generals, and the weakened state of Qi and Chu during the time of his rule. However, one famous event suggests, if the accounts we have of it are at all accurate, that the First Emperor was seen as the controlling force of Qin politics. That event is the failed assassination attempt of Jing Ke,” described below. Jing Ke had an opportunity to kill the great Emperor Qin but failed to do so. /+/

Story of Jing Ke

Dr. Eno wrote: “Jing Ke was a native of Wey who was well educated and skilled in swordsmanship. He seems to have attempted a career as a persuader, but failing to attain any position in Wey he began a life of wandering and eventually wound up in the state of Yan. In Yan, a famous swordsman recognized that Jing had great qualities as a man of valor and became his patron. Jing himself lived a life of insignificance in Yan, keeping company with a dog butcher and a lute player named Gao, with whom he would drink in the marketplace day after day until all three collapsed in maudlin tears, moved by Gao’s remarkable musical abilities.[Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University, based Shiji 86 from “The Shinji” (94 B.C.) by Sima Qian /+/ ]

“About 230 B.C., the crown prince of Yan, who had been residing in Qin as a diplomatic hostage, fled back to his home state in resentment over the poor treatment he had received at the hands of King Zheng of Qin. Holding this grudge against Qin, he became alarmed to see the forces of Qin begin their march eastward, destroying the state of Han and threatening the other eastern states. /+/

“Shortly thereafter, a General Fan of Qin who had committed some offense against the throne fled to Yan, where he was harbored by the crown prince. The prince’s advisors were anxious to return the general to Qin, but the prince would not hear of any plan that would accord with wishes of Qin. Understanding, however, the danger of openly provoking the king of Qin in this way, the prince set out to find a man who could relieve the threat of Qin by assassinating King Zheng. His courtiers recommended the swordsman who had become Jing Ke’s patron, but when they met, the man disappointed him. /+/

““They say,” the swordsman said to the prince, “that when a thoroughbred is in its prime it can gallop 1000 li in a day, but when it is old, the weakest nag can outdistance it. It seems that you have heard reports of how I was in my prime and do not realize that now my strength has left me. Nevertheless, I have a friend named Master Jing who could be consulted for a task serving the state.”

Jing Ke’s Plan to Assassinate Emperor Qin

Dr. Eno wrote: “The prince eagerly requested an interview, but added, as the swordsman departed, “These matters are of vital concern to the state. Please do not let a word of this leak out!”The swordsman sought out Jing Ke and conveyed to him the wishes of the prince. Then, speaking of the prince’s caution to keep silent he said, “If my actions have given him cause to mistrust me, I am not a worthy warrior. When you visit the prince, tell him that I died without betraying him.” And with that he slit his throat and died. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University, based Shiji 86 (94 B.C.) by Sima Qian /+/ ]

“The death of his patron not only spurred Jing Ke on to serve the prince, but assured that the prince would trust Jing Ke to the utmost. Together they set out to determine how Jing Ke could either coerce a favorable peace with the king of Qin or assassinate him. But how was Jing Ke to gain admission to the Qin court?Jing Ke proposed to kill General Fan and carry his head to Qin as a token of Yan’s submission, so that he could, in presenting this trophy, come close to the person of the king. But the prince refused. “I could never bear to betray the trust of a worthy man for the sake of my own wishes,” he said. “I must ask that you think of some other plan.”

Despite this, Jing Ke decided to go directly to General Fan. “In retaliation for your actions,” he said, “Qin has killed your parents and all the members of your family. I am told that Qin has offered a reward of 1000 catties of gold and a city of 10,000 households for your head. What shall we do?” Then he revealed his plan. “Give me your head so that I can present it to the king of Qin! He will surely receive me with delight. Then with my left hand I will grab hold of his sleeve and with my right I will stab him in the chest – your wrongs will all be avenged.” Baring his shoulder, General Fan stepped towards Jing Ke. “Day and night I gnash my teeth and eat out my heart searching for some plan. Now you have shown me the way!” And with this he slit his throat and died.” /+/

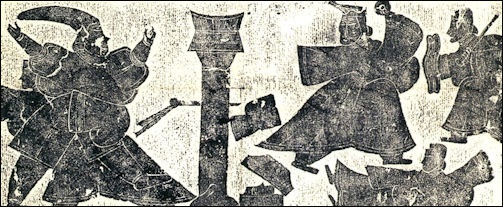

Assassination attempt of Emperor Qin

Jing Ke’s Attempt to Assassinate Emperor Qin

Dr. Eno wrote: “The prince was greatly upset, but had no choice now but to carry forth Jing Ke’s plan. He equipped him with an assistant and gave him a set of maps to the state of Yan as a further token of good faith to Qin. He ordered that a stiletto dagger with a poisoned tip be cast and prepared for Jing Ke’s mission, and had it tested on several men, all of whom died instantly. Then Jing Ke set out. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University, based Shiji 86 (94 B.C.) by Sima Qian /+/ ]

“At the crossing of the River Yi, the party of men who had joined to send off Jing Ke and his assistant stopped to sacrifice to the spirit of the road and bid their friend farewell. Gao the lute player began to play and Jing Ke stood forward and sang:

Xiao, xiao, cries the wind,

and the waters of the Yi run cold;

The brave warrior, once he has gone,

will never again return.

As all the followers wept, Jing set off without so much as looking back. /+/

“The king of Qin was so delighted with the news that an envoy had arrived from Yan bearing the head of General Fan that he called a full court assembly to receive him. Jing Ke entered the palace throne room carrying the box with General Fan’s head, his assistant trailing behind with the case of maps. But before they had reached the throne, the assistant’s courage ran out and he began to tremble visibly, attracting the attention of the courtiers. Jing Ke turned, and realizing that all was about to be lost he let out a great laugh. “This bumpkin from the northern borders is trembling to see the Son of Heaven! Pardon him, your majesty! Let me complete my mission to you.” Then taking the map case along with General Fan’s head, he approached the throne and presented them to the king. /+/

“When the king opened the container of maps, the dagger was revealed. Jing Ke had hidden it there because the laws of Qin forbade any man to carry arms in court in order to safeguard the person of the king. Jing Ke instantly seized the dagger and gripped the king by the sleeve. But instead of plunging the knife, he hesitated, intending first to whisper to the king a proposal for peace and release him if it were accepted. /+/

“The king, however, did not hesitate. He leapt from the throne, ripping his sleeve, and dashed away from Jing Ke, his scabbard tangled in his robes so that he could not draw his sword. Jing Ke pursued him to a bronze pillar and the two began a chase around the pillar while the unarmed courtiers watched helplessly. Only the king’s physician attempted to intervene, thrashing at Jing Ke with his medicine bag. Eventually, the king was able to push back his scabbard and draw his sword. He slashed Jing Ke in the thigh, and as he fell, Jing Ke hurled the poisoned dagger at the king. But the dagger struck the pillar and the king was saved. He cut down Jing Ke, who soon lay sprawled against the pillar, laughing.“I failed because I tried to threaten you without killing you!” he cried. And then the king’s guard silenced him forever.” /+/

Aftermath and Meaning of of Jing Ke’s Assassination Attempt of Emperor Qin

Dr. Eno wrote: “Yan fell in 222 B.C., and after the conquest, the First Emperor made every effort to hunt down all the men who had been involved in the assassination attempt. His agents failed, however, to find the lutenist Gao, who went into hiding and covered up his skills as a lutenist in fear that he would be identified. But after a time, his skills came to light and his fame spread, and at length he was summoned to play for the emperor. As he played, an attendant identified him, and the emperor, unable to bear killing so fine a musician, ordered that Gao’s eyes be put out. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University, based Shiji 86 (94 B.C.) by Sima Qian /+/ ]

“Later, the emperor often ordered that Gao be brought to court to play, and Gao, each time he was led into court, would move his mat a bit closer to the emperor. At last, when he believed the emperor no longer feared him, Gao hid a heavy lead weight in his lute and approached nearly to the side of the throne. Then, in the midst of his playing, he suddenly raised his lute and attempted to strike the emperor dead. But once again, the emperor dodged an assassin, and Gao was immediately executed, ending the last breath of Jing Ke’s plot. /+/

“While assassinations of rulers were about as common as dinner parties in Classical China, etiquette demanded that one murder one’s own lord, not the ruler of another state. The accepted goal of assassination was the acquisition of power, although personal revenge could also play a role (recall the attempts of Wu Zixu to bring about the death of the king of Chu, and General Fan’s role here). We do not often see assassination employed as a part of state policy because rulers were not generally the determining factor in an enemy state’s political behavior. To sabotage a state, it was far more effective to murder or bribe key ministers, or to bring about their downfall by means of slander. /+/

“The plot of Jing Ke and the prince of Yan may be viewed as a personal matter – the prince had been slighted in Qin, and the “Shiji” tells us that his resentment was strong because he had been a boyhood friend of the First Emperor when both were sons of royal hostages in the state of Zhao. But the political goals of the assassination figure in every version of the story. All who recorded it saw it as an attempt to deflect the whirlwind military campaigns of Qin by eliminating their guiding force, the king – not Li Si.: /+/

Zhang Yimou’s Movie About Jing Ke’s Attempt to Assassinate Emperor Qin

Famed Chinese film director Zhang Yimou’s made a movie about Jing Ke’s failed attempt to assassinate Emperor Qin. The film known as “Hero” was a big-budget, big-name, Hollywood-style epic star film released in 2002. Described by Time magazine as a “a masterpiece” and by the Los Angeles Times as a “visual knockout," it is a dazzling, visual film, noted for its stunning use of color and imaginative use of “Crouching Tiger”-style digitalized action sequences. The censors in Beijing liked it too but some international critics condemned it as overproduced and silly and some Chinese critics claimed it promoted servility and glossed over the horrible things done by Emperor Qin. “Hero” expresses support for the idea that an all-powerful state is necessary to preserve unity and stability.Some critics panned Hero as being an “implicit homage to authoritarian rule." Government critics hailed it as a “new starting point."

Like the classic Rashomon, a single story is told several times from different perspectives as the assassin struggles to overcomes three rivals. The film is divided into three main sections, each dominated by a single color — red, blue and white, with green thrown in for flashbacks. The blue scenes were shot at the beautiful lakes in the Jiuzhaigou region of China and were said to be inspired by the lake's color. The white scene were shot in desert near the Kazakhstan border.

Hero was the most internationally successful Chinese film export until the mid 2000s and remains one of the top-grossing foreign-language films to appear in American theaters. Costing $30 million to make, Hero features grand battle scenes, martial art choreography and big names like Jet Li, Tony Leung, Maggie Cheung and Zhang Ziyi. It was a box office smash in China, where it ranked second only to Titanic as the highest grossing film ever in China. The United States version— with an imprimatur from Quenton Tarantino and with 20 minutes edited out to speed up the pace and make it more palatable to American audiences — came out in 2004. It broke box office records there for an Asian film. As of early 2005 it had earned $53.5 million in the United States and $155 million worldwide. The Chinese government lobbied hard to get the film an Academy Award nomination in 2002 for best foreign film and then lobbied hard to get it to win.”

Emperor Qin’s Quest for Immortality

Mt. Tai

In his later years Emperor Qin became obsessed with finding "the elixir of immortality” and seeking other ways to circumvent death. In Imperial China it was thought that people could become immortal by climbing the right mountains and consuming elixirs made with the things like mercury, arsenic, jade, gold, special fungi, wild mushrooms and other herbs. The cult of immortality was linked with Taoism.

Emperor Qin alienated his subjects and spent a large portion of his kingdom's wealth in his pursuit of the elixir of immortality and was taken advantage of by many charlatans who promised to find it. In addition, he went to great lengths to avoid foods and drinks that made him belch and fart because it was widely believed at the time that these and other bodily functions robbed people of their vital life energy qi, hastening death. Qin also had a 28-mile pathway constructed from his palace to a spike-shaped peak where it was believed immortals ascended to heaven.

Dr. Eno wrote: “It appears from many accounts that the First Emperor set great store by those who professed to possess the arts of magic and immortality characteristic of popular religion, and lavishly expended government funds in pursuit of these superstitious goals. As mentioned earlier, the First Emperor took a great liking to the region of Langye on the Shandong coast. Langye was the locality most prominently associated with the magical systems of a variety of practitioners known as “fangshi”, or “men of the arts.” During the last century of the Warring States era, Qi had become famous as the home of these “fangshi”, and they were sharp competitors with Confucians, also a native movement of the Shandong peninsula. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“One of the best known cults among the many “fangshi” arts was the cult of immortality. Practitioners had specialized knowledge concerning the formulas of certain rare and secret vegetable and mineral elixirs that could engender immortality in ordinary men. They also knew all that mortals could know about the realms and practices of the immortals, many of whom lived on islands in the Pacific opposite the Shandong coast, especially on the island of Penglai.” /+/

Emperor Qin’s Pursuit of the Elixir of Immortality

Emperor Qin sent off various officials, emissaries and explorers in search immortality herbs and potions. According to one story, one of Qin’s ministers, Cheng On Kee, found the "herb of immortality" growing in abundance in the White Cloud Hills near Canton. After eating some he was surprised that the rest had disappeared. Afraid of returning to Emperor Qin empty handed, the minister leaped off a cliff and, because he had eaten the herb, was snatched by a crane and taken to heaven.

Emperor Qin sent a mariner named Hsu Fu to search the Pacific for the "drug of immortality." One his second attempt he failed to return. Some have speculated he may have made it to America but never made it back. Adventurer Tim Severin tried to duplicate the voyage with an ocean going raft, made of Vietnamese bamboo, rigging sails and hand-woven rattan ropes. He too never made it: a succession of storms waterlogged the bamboo and Severin and his crew had to be rescued. Other emperors were equally obsessed with immortality. Two hundred years after Emperor Qin another emperor spent what some said was the equivalent of the Manhattan Project on the development of a pill of immortality. [National Geographic Geographica, April 1994].

In another tale, one alchemist made it back and reported that the herb or immortality could be found on an island guarded by a giant fish. According to this story the Emperor decided to seek the herb himself. He managed to kill the giant fish with an arrow he fired from a crossbow but before he could claim his prize he died of a fatal disease. Some scholars have theorized that these tales are based on the reality that Qin simply was very sick and sent emissaries to find medicines that could heal him.

Dr. Eno wrote: “In 219 B.C., after erecting the great inscription at Langye translated earlier, the emperor was approached by an immortalist from Qi named Xu Fu, who informed him of the islands” linked to immortality off Shandong. “He told the emperor that the elixirs of everlasting life could be distilled from herbs that grew upon Penglai, and requested funds for a sea voyage to bring these back. He said that for such a voyage to be successful, it would be necessary for him to sail with a large retinue of young boys and girls. The emperor, fascinated by these exotic eastern teachings, eagerly bestowed upon Xu Fu funds adequate to sustain several thousand young people on the proposed trip. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“Xu Fu apparently made a number of such trips on behalf of the First Emperor. Several times, he and his crew got near enough to these magical islands to sight them through the mist, but each time, an enormous fish interposed itself and blocked their way, leaving Captain Xu Fu no alternative but to return in defeat, and request (and receive) funds for another try. /+/

In 2019, Archaeology magazine reported: “A wealthy individual living 2,000 years ago in Henan Province was buried with an assortment of fine bronze, jade, and ceramic objects. Amid this trove was a jar containing a yellow liquid, which chemical analysis has revealed to be a mixture of potassium nitrate and alunite — and not rice wine as first thought. The minerals are the main ingredients of the legendary “elixir of immortality” mentioned in ancient Chinese texts. [Source: Archaeology magazine, May-June 2019]

Emperor Qin’s Becomes Increasing Suspicious and Isolated

Penglai mythical island, reputed home of the Elixer of Immortality

In the last years of his life, Emperor Qin became paranoid and changed his sleeping quarters every night after he was nearly slain by a man who delivered the head of bitter enemy. Emperor Qin began building the massive tomb for himself and a terra cotta army to guard it when he was still alive. Jessica Rawson, an expert on Emperor Qin at the British Museum, told the Daily Yomiuri, “He saw himself not just as the ruler of the world but as the ruler of the universe. And he saw himself as a cosmic figure, and that is perhaps not unusual in early Chinese emperors — they all believed they ruled with the mandate of heaven. But in a sense he saw himself almost as a deity, alongside the great cosmic spirits."

Around the time the quest for immortality was at its peak, Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: the emperor began to grow increasingly secretive. We are told that one of his "fangshi" convinced him that the cause of his inability to procure the herbs of immortality was due to black magic exercised by some enemy. To counter the magic, it would be necessary for the emperor to conceal his whereabouts so that the magic could not find its target. Consequently, the emperor had a network of elevated walkways and walled roads constructed so that none would be able to detect his movements. Access to the emperor became restricted to a few high ministers and the emperor’s eunuch attendants. The court began to close down. “Even the heir apparent felt the effects of this change. When, in 212 B.C., he attempted to remonstrate with his father about the growing unpopularity of the state’s increasingly severe policies, the First Emperor ordered his son to leave the capital area and travel to the northern borders to supervise the wall-building activities of General Meng Tian. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“If we consider the entire course of the First Emperor’s career, we can see that he does, in fact, appear to have had a considerable influence on the fate of the Qin Dynasty. The assassination attempt of Jing Ke prior to the conquest suggests that he was no passive patrician lord presiding over a court of talented ministers, he was a key factor in the rise of the Qin. /+/

“After the conquest, the emperor’s active efforts to define the role of the new universal ruler probably contributed to the rapid establishment of Qin authority, as reflected in the astonishing accomplishments that were made during the First Emperor’s eleven-year imperial reign. Later, his personal obsessions with immortality and his willingness to increase the severity of Qin tyranny beyond its productive limit probably laid the foundations for the downfall of Qin. /+/

Death of Emperor Qin

In 206 B.C.,Qin Shi Huang died at the age of 49, after an 11 year reign, while on a tour his empire. When he died only four people knew about his death. They kept his death secret because of concerns over chaos, murder and war breaking out in a fight for the succession to his throne, and to further their own ambitions. On the trip back to Xian, the smell of Emperor Qin’s dead body was masked by smelly fish.

Dr. Eno wrote: “The gruesome circumstances surrounding the death of the First Emperor delighted Confucian historians throughout the centuries of traditional Chinese history. The First Emperor’s postmortem fate, as portrayed by the “Shiji”, parallels in some respects the dreary fate that met the greatest ruler of the Classical period, Duke Huan of Qi. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“The First Emperor died near Langye, the point from which he had first dispatched Xu Fu to seek the isles of the immortals. The emperor returned there in 210 B.C., accompanied by Li Si, his most intimate eunuch attendant, a man named Zhao Gao, the emperor’s favorite son, a younger boy named Huhai, and a large entourage of eunuchs and palace guards. While at Langye, he dreamed that he was fighting with the spirit of the sea, who appeared to him as a man. A soothsayer of dreams interpreted this as a sign that the emperor’s quest for immortality was, in fact, being obstructed by the spirit of the sea. “The water spirit cannot himself be seen,” he told the king, “but he may appear as a huge fish.” “This seemed to confirm the reports that the emperor had received from Xu Fu. He ordered that all future expeditions to Penglai be equipped with gear for capturing so great a fish. In the meantime, he himself marched north along the coast, searching for his enemy, the spirit of the sea. At length, he did indeed see a huge fish swimming in the waters near the coast, and using a powerful crossbow, he killed it. But soon thereafter, he fell ill. /+/

Xu Fu's expedition for the Elixer of Immortality

“Apparently, the spirit of the sea exacted swift revenge. The emperor died within days. The only people who were aware of the emperor’s death were his son Huhai, Li Si, the eunuch Zhao Gao, and a few of Zhao’s eunuch subordinates. Huhai and the two ministers found themselves faced with a perilous choice. The emperor’s rightful heir was a man of good reputation and a close intimate of General Meng Tian, the most powerful of the Qin military leaders. It was clear to all three men that as soon as the prince was informed of the death of his father, he would cast off Li Si and Zhao Gao and appoint Meng Tian – no friend to either – as prime minister. Huhai, one of twenty sons of the emperor, would live out his life in obscurity. The three hatched a plan. They informed no one among the imperial entourage of the emperor’s death. They continued to carry food to the emperor’s curtained tent or carriage as before. Meanwhile, they forged a letter to the heir apparent in the emperor’s name, instructing him to commit suicide for his unfilial admonitions to his father, and Meng Tian to do likewise. After that had been sent north, they forged a testimonial edict, said to have been entrusted by the emperor to Li Si, designating Huhai as the new heir apparent. Then they ordered the imperial procession to return to the capital. As the weather was hot, the emperor’s corpse soon began to decay, and the plotters ordered that fish be loaded on the carts near the imperial carriage in order to mask the smell. /+/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Emperor Qin, Early Great Wall, Ohio State University.

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021