SONG DYNASTY LANDSCAPE PAINTING

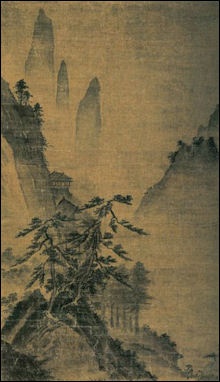

Sitting Alone by a stream by Fan Kuan

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “The Five Dynasties and Song periods witnessed a gradual shift in painting subject matter in favor of landscapes. In earlier dynasties landscapes were more often the settings for human dramas than primary subject matter. During the tenth and eleventh centuries, several landscape painters of great skill and renown produced large-scale landscape paintings, which are today considered some of the greatest artistic monuments in the history of Chinese visual culture. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“These landscape paintings usually centered on mountains. Mountains had long been seen as sacred places in China — the homes of immortals, close to the heavens. Philosophical interest in nature could also have contributed to the rise of landscape painting, including both Daoist stress on how minor the human presence is in the vastness of the cosmos and Neo-Confucian interest in the patterns or principles that underlie all phenomena, natural and social./=\

“The essays that have been left by a handful of prominent landscape painters of this period indicate that pictures of mountains and water (shan shui, the literal translation of the Chinese term for landscape) were heavily invested with the numinous qualities of the natural world. Landscape paintings allowed viewers to travel in their imaginations, perhaps the natural antidote to urban or official life. /=\

“Landscape painting was not entirely new to the Five Dynasties and Song. Most of the landscapes painted during the Tang were executed in blue and green mineral-based pigments, which gave the painting surface a jewel-like quality.At first glance, Song and Yuan landscapes seem to conform to a narrow set of compositional types, with requisite central mountains, hidden temples, and scholars strolling along a path. In fact, the landscape tradition developed slowly as painters gained technical facility and consciously chose to allude to earlier styles or bring out philosophical or political ideas in their work.” /=\

Southern Song landscape painting differed from Northern Song landscape painting in that Southern Song style looked inward, while Northern Song style extended outward. During the Northern Song period, rulers aimed to unite society and extend their influence over elites with a common set of values. In the Southern Song painters became of interested in personal expression. Northern Song landscapes were endorsed by the government as “real landscape”, since the court appreciated the representation relationship between art and the external world, rather than the relationship between art and the artists inner voice. [Source: Wikipedia]

Good Websites and Sources on the Song Dynasty: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; San.beck.org san.beck.org ; Tang Dynasty: Wikipedia ; Google Book: China’s Golden Age: Everday Life in the Tang Dynasty by Charles Benn books.google.com/books; Chinese History: Chinese Text Project ctext.org ; 3) Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu ; Chaos Group of University of Maryland chaos.umd.edu/history/toc ; 2) WWW VL: History China vlib.iue.it/history/asia ; 3) Wikipedia article on the History of China Wikipedia Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TANG, SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY (A.D.960-1279) factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY (960-1279) ADVANCES factsanddetails.com; CHINESE PAINTING: THEMES, STYLES, AIMS AND IDEAS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTING FORMATS AND MATERIALS: INK, SEALS, HANDSCROLLS, ALBUM LEAVES AND FANS factsanddetails.com ; SUBJECTS OF CHINESE PAINTING: INSECTS, FISH, MOUNTAINS AND WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; TANG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ANIMAL, RELIGIOUS AND FIGURE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SU SHI (SU DONGPO)—THE QUINTESSENTIAL SCHOLAR-OFFICIAL-POET factsanddetails.com; WANG ANSHI, HIS REFORMS AND HIS BATTLE WITH SIMA GUANG factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY CULTURE: TEA-HOUSE THEATER, POETRY AND CHEAP BOOKS factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY CERAMICS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Paintings During The Song Dynasty” by Tom Geng Amazon.com “Beyond Representation: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, 8th-14th Century” (Princeton Monographs in Art and Archaeology, No 48) by Wen C. Fong Amazon.com “Empresses, Art, and Agency in Song Dynasty China” by Hui-shu Lee Amazon.com “Porcelain of the Song Dynasty” by Palace Museum Amazon.com “Song Dynasty Ceramics” (Victoria & Albert Museum Far Eastern) by Rose Kerr Amazon.com “Housing, Clothing, Cooking, from Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion 1250-1276" by Jacques Gernet Amazon.com ; “The Making of Song Dynasty History: Sources and Narratives, 960–1279 CE” by Charles Hartman Amazon.com “Chinese Urbanism: Urban Form and Life in the Tang-song Dynasties” by Jing Xie Amazon.com “The Reunification of China” by Peter Lorge Amazon.com; Painting: “Chinese Painting” by James Cahill (Rizzoli 1985) Amazon.com; “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” by Richard M. Barnhart, et al. (Yale University Press, 1997); Amazon.com; “Masterpieces of Chinese Painting 700-1900" by Hongxing Zhang Amazon.com; “How to Read Chinese Paintings” by Maxwell K. Hearn (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008) Amazon.com; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Northern Song (960-1127) Landscape Painting

Gentleman Viewing the Moon by Ma Yuan

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In landscape painting, the National Palace Museum's three "national treasures" of Fan K'uan's "Travelers Among Mountains and Streams" (ca. 1000), Guo Xi's "Early Spring" (1072), and Li T'ang's "Windy Pines Among a Myriad Valleys" (1124) offer unique presentation of the achievements during one of the first peaks in landscape painting in the Northern Sung and insight into developments that took place within more than a hundred years. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“In Sung dynasty records on painting, the painter of "Travelers Among Mountains and Streams", Fan K'uan, is described as a specialist "famous in his day". From the viewpoint of regional style, some scholars consider this painting as an ideal representative of northern landscape painting in China. Others, from its format of arrangement, believe this masterpiece embodies a shift in compositional viewpoint that took place in Chinese painting at the time. In other words, the layered "high distance" composition derived from the T'ang dynasty has been developed into a perfected realm, this piece being considered as a representative of "monumental landscape" painting of the Northern Sung. Still other scholars, from a more philosophical viewpoint of the "Tao" (Way), believe that this work expresses the ideal of a harmonious relationship between humans and nature. \=/

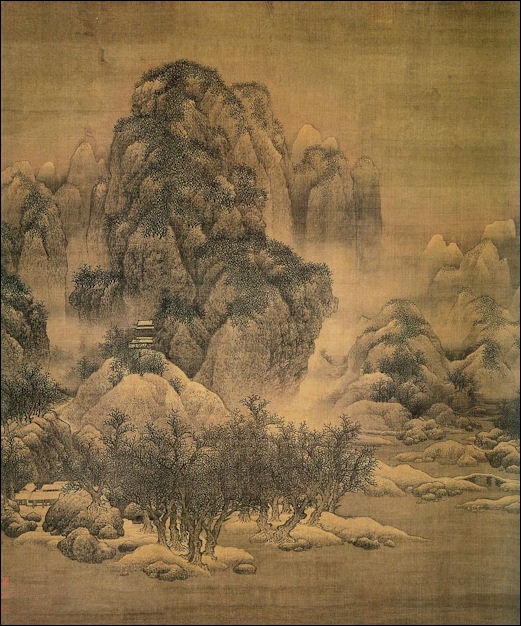

“More than seventy years later, the court painter Guo Xi in Emperor Shen-tsung's reign (1068-1085) continued in the monumental landscape manner of "Travelers Among Mountains and Streams". In "Early Spring", he used the compositional formats of "high distance", "deep distance", and "level distance" to construct a full-scene "true landscape". Appearing in the painting are mountains and streams, woods, and buildings that appear to be of solid substance as well as elements of less concrete forms, such as clouds and mists, haze, and atmosphere, revealing the extraordinary painting skills of the artist in terms of his manipulation of solid and void. The logical relationship between the mountains, rocks, trees, and water has also been explained by some scholars as symbolic of a harmonious and orderly relationship in nature and among people in an ideal empire. \=/

“Early Spring” by Guo Xi (1023-ca. 1085) is a hanging scroll, ink and light colors on silk, (158.3 x 108.1 centimeters). A native of Henan province, Guo Xi entitled this work "Early Spring" and signed it "Painted by Guo Xi in the jen-tzu year (1072)." Coming after "Travelers Among Mountains and Streams" by Fan K'uan, this is one of the Museum's masterpieces of Northern Sung monumental landscape painting. Fan K'uan represented the solemn and eternal features of the mountains, while Kuo captured the essence of spring with his evanescent and atmospheric use of ink washes. With "cloud-head" texture strokes for the mountain forms and "crab-claw" ones for the trees, the landscape in this painting seems to almost pulsate, flow, and disappear (only to reappear again), suggesting the hidden forces of Nature and the cosmos at work. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“In both "Travelers Among Mountains and Streams" and "Early Spring", though ordinary figures are shown as miniscule in relation to the mountains, the artists painstakingly rendered their status, clothing, actions, and expressions. This notion of realism and narrative derives from the travel landscapes of the T'ang and Five Dynasties period. In the middle Northern Sung, during the latter half of the 11th century, this reached a perfection of expression. The 12th century also marks the last major imperial period of the Northern Sung under Emperor Hui-tsung (r. 1101-1125). In his reign, painting was fused with poetry, and abstract images from literary sources and symbolic techniques were injected into painting. "Windy Pines Among a Myriad Valleys", done in 1124 by Li T'ang, differs from the presentation of the previous two works. It includes no narrative figures or buildings to distract from the focus of the scenery. Rather, it uses the deep mountains, clouds, pines, waterfall, and rapids to suggest the theme of listening to wind rustling through pines deep in a valley, which was often mentioned in poetry of the period.” \=/

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Fan Kuan's “Travelers Among Mountains and Streams,” nearly seven feet tall, focuses on a central majestic mountain. The foreground, presented at eye level, is executed in crisp, well-defined brush strokes. Jutting boulders, tough scrub trees, a mule train on the road, and a temple in the forest on the cliff are all vividly depicted. Four or five different types of trees are depicted. Fan Kuan creates rocks, trees, and all other elements in the painting through texture strokes and washes. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Southern Song (1127-1279) Landscape Paintings

“Travelers Among Mountains and Streams" by Fan Kuan

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “In the Southern Song period (1127-1279), after the capital was relocated to Hangzhou because of the loss of Kaifeng and most of north China to the Jurchen Jin dynasty, court painters continued to paint landscapes, but favored small formats and more lyrical treatments. By this time, painters were frequently exploiting the connections between poetry and painting, either by making a painting to capture poetic lines or writing a new poem to bring out features of a painting they had done.” Famous painters from this period include Ma Yuan (active 1190-1224) and Xia Gui (active c. 1180-1224). [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The composition of landscape paintings... went from the full monumental scenes of the Northern Song to the one-corner arrangements of the Southern Song, expressing a new visual aesthetic of scenery viewed as both far and near, dense and expansive, open and closed, and high and low. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Sitting on Rocks Gazing at Clouds” by Li Tang (ca. 1070-after 1150) is an ink and colors on silk album leaf, measuring 27.7 x 30 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: In this work is an arrangement of more forms that distinguishes it from the one-corner compositions of many Southern Song landscape paintings, in which a large portion is left blank to suggest mist. Close examination of the painting, however, still clearly reveals a cleverly arranged diagonal composition. Based on this imaginary diagonal line, the upper left and lower right portions show an interesting relationship of contrasts between void and solid, respectively. Two figures in the lower right wear wide robes and dangle their feet in the water, admiring the beautiful scenery in the upper left. “The fine scenery here is filled with trees, the rugged cliffs painted with blue-and-green colors and ink washes, to which ochre has been added for variation. Delicately infused with a compelling realism of rocky texture in Li Tang's "Wind in Pines Among a Myriad Valleys" is the exquisite sentiment of Zhao Lingrang's intimate scenery, making this not far removed from the characteristics of Northern Song landscape painting. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Pure Distance of Mountains and Streams” by Hsia Kuei (1180-1230) is an ink on paper handscroll, measuring 46.5 x 889.1 centimeters. Hsia Kuei was as famous as his contemporary Ma Yuan, hence their designation "Ma-Hsia." This is the most important surviving work by Hsia Kuei. Hsia's use of brushwork was refined. His representation of landscapes with large "axe-cut" texture strokes was even more simplified and natural than that of Li T'ang. The ink varies in tone from jet-black to washes of gray. This long scroll can be divided into three distinct sections, with each one revealing a contrast between near and far as well as solid and void from a variety of angles. Hsia Kuei took the spatial depth and softness of ink wash in the middle Southern Sung to its extreme. His ability to control and convey the essence of water and ink is especially impressive. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Pure and Remote Mountains and Streams” by Xia Gui (1180-ca. 1230) is an ink on paper handscroll, measuring 46.5 x 889.1 centimeters: “The handscroll viewed from right to left depicts intersecting vistas of mountains and water, sometimes expansive and at other times dense, forming an extremely rhythmic arrangement to the composition. The painter here used "axe-cut" texture strokes to describe the hard, rocky features of the land and added plenty of water to the brush, expressing rich and moist variations of ink tones. The trembling brushwork in the painting suggests a sense of branch tips moving in the wind. In fact, the ability to delicately grasp this kind of formless sensory experience can be considered one of the most refined aspects of Southern Song painting. Xia Gui (style name Yuyu) was a native of Qiantang (modern Hangzhou, Zhejiang) and a painter at the Southern Song court. Entering service late in the reign of Emperor Xiaozong, he reached the height of his career under Emperor Ningzong, his period of activity also extending into the court of Lizong. \=/

Plum, Bamboo, and Other Plants in Song Paintings

Ma Yuan landscape

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Amateur painters, from Su Shi and his friends on, had favored painting bamboo and flowering plum in ink monochrome, in part at least because those skilled in the use of the brush for calligraphy could master these genres relatively easily. Bamboo, plum, orchid, pine, and other plants had over the centuries acquired a rich range of associated meanings, largely from poetry. In Song and especially Yuan times, scholar painters began to systematically exploit these possibilities for conveying meaning through their pictures. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“Orchids, ever since Qu Yuan in the Warring States Period, had been associated with the virtues of the high-principled man. The orchid is fragile, modest, but its fragrance penetrates into hidden places. In “Orchid” by Zheng Sixiao (1241-1318), the artist here has inscribed a poem on the painting that refers to the coolness and refreshing quality of the autumn melon for one who is experiencing the full heat of summer. /=\

“Wu Zhen, the painter of rock and bamboo paintings, was a true recluse. He rarely left his hometown and made his living by fortune-telling and selling paintings. Although bamboo leaves could be painted with single, calligraphic strokes, of the sort Wu Zhen used above, some literati painters also did bamboo with outline and fill techniques associated more with professional and court painters. One of the qualities sought by scholar painters was simplicity, plainness, understatement, seen as the opposite of showy, flashy paintings. Paintings of plums often were done using very simple strokes.” /=\

Song Landscape Painters

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““In the Song Dynasty (960-1279), landscape painters such as Li Cheng (916-967), Fan Kuan (10th century), Guo Xi (11th century) and Li Tang (ca. 1049-after 1130) created new manners based on previous traditions. The transition in compositional arrangement from grand mountains to intimate scenery also reflected in part the political, cultural, and economic shift to the south. Famous works by Li Cheng include his masterpiece “A Solitary Temple Amid Clearing Peaks” and “Reading the Stele” and “Small Wintry Grove” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Guided by the taste of the emperor, painters at the court academy focused on observing nature combined with "poetic sentiment" to reinforce the expression of both subject and artist. Painters were also inspired by things around them, leading even to the depiction of technical and architectural elements in the late 11th century. The focus on poetic sentiment led to the combination of painting, poetry, and calligraphy (the "Three Perfections") in the same work (often as an album leaf or fan) by the Southern Song (1127-1279). Scholars earlier in the Northern Song (960-1126) thought that painting as an art had to go beyond just the "appearance of forms" in order to express the ideas and cultivation of the artist. This became the foundation of the movement known as literati (scholar) painting.

The art of Li Cheng, Fan Kuan and Guo Xi form the three pillars of landscape painting in the Northern Song. In texts and records, Li Cheng stands out as the oldest and most renowned in terms of his refined use of ink and brush. Among the students of the Li Cheng style, Guo Xi was the one who was best able to follow in Li's footsteps. Kuo manipulated the contrast between solid and void as well as light and dark to suggest a landscape almost alive as it writhes in and out of the mist. His superb handling of atmosphere was unrivaled, allowing him to stand on equal footing with Li Cheng. Later artists took the styles of these two masters as models for emulation, and hence the birth of the Li-Kuo tradition. Such Yuan dynasty artists as Ts'ao Chih-po, Chu Te-jun, and Tang Ti all studied the Li-Kuo style, but each had his own interpretation. Such Ming artists as Wu Wei, Hsieh Shih-ch'en, and Tung Ch'i-chang, as well as the Four Wangs of the Early Qing and Yun Shou-p'ing, were also versed in the Li-Kuo manner, establishing it as one of the hallmarks of Chinese landscape painting.

Ma Yuan, scholar by a waterfall

Song Landscape Paintings

“Li Cheng, a descendant of the Tang imperial family, specialized in painting flat distance landscapes of misty water and trees using washes of ink. “A Wintry Forest” is attributed to him. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Through a forest winds a quickly flowing stream that dashes and splashes against the rocks. Tall trees appear on either side of the stream, and bands of mist float among the treetops. The brushwork in the trees is particularly strong and energetic-the branches looking like twisting dragon claws, similar to the distinctive crab-claw style of painting trees in the Li Cheng and Guo Xi tradition. In terms of style, this may be a work by a Chin dynasty artist of the 12th century following the Li-Kuo tradition. Li Cheng, style name Xianxi, descended from the Tang imperial clan in Chang’an and moved to Yingqiu, Shandong, in the Five Dynasties era.

“Mountain of Jade Floating in the Great River” was made an anonymous Song Dynasty painter. “ “The waves of a large river lap at the shores of rocky outcroppings. Two riverboats are moored in the foreground as a peak rises in the center of the painting and is surrounded by complementary rocks. Trees and temple buildings punctuate the mountain, providing descriptive details. The use of brush and ink is similar to those in Guo Xi's Early Spring, while the spacious composition is related to Autumn Colors over Streams and Mountains by Hui-tsung. Perhaps a follower of Guo Xi did this work in Hui-tsung's Hsuan-ho era (1119-1125). This is the 9th leaf from the album Collected Famous Paintings. Bearing no seal or signature, it was attributed to Li Tang, a 12th-century court painter famous for axe-cut texture strokes.

“Soughing Wind Among Mountain Pines” by Li Tang, Song Dynasty, is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 188.7 x 139.8 centimeters. Li Tang, a native of Ho-yang, is also said to have lived from about 1070 to after 1150. He served in the Hanlin Academy of Painting under Emperor Hui-tsung (r. 1101-1125) of the Northern Song. Sometime between 1127 and 1130, after the fall of the Northern Song in 1126 to northern invaders, Li escaped to the south, where the government became re-established as the Southern Song (1127-1279) at Hangzhou. There he re-entered the Painting Academy, which was set up during the period from 1131 and 1162. He went on to receive the title of Gentleman of Complete Loyalty and the prestigious Gold Belt. He also became a Painter-in-Attendance and was an important figure in court painting at the time.

“After the Museum's “Travelers Among Mountains and Streams" by Fan Kuan and “Early Spring" by Guo Xi of the Northern Song, this is late Northern Song masterpiece represents the next stage in monumental landscape painting of the period. Li Tang's signature appears on a slender peak to the left and reads, Painted by Li Tang of Ho-yang in spring of the chia-ch'en year [1124] of the Hsuan-ho Reign of the Great Sung." By this time, Li was already advanced in age, but his brushwork is still quite strong and inspired. With the main peak located in the center, clouds wrap around high and low peaks on either side. The cliffs and peaks are imposing and rugged, and their texturing was done using brush strokes similar to wood chopped by an axe (and hence became known as axe-cut" strokes). Li Tang employed a high distance compositional formula to make the atmosphere appear solemn. However, he also expanded the composition in front to include foreground woods and streams, which make the scene more intimate and closer to the viewer, and hence more comprehensible as a natural landscape. This trend towards closer visions continue in Song painting, making this work an important forerunner of the intimate style of Southern Song landscape painting.

“Spring Mountains and Auspicious Pines” by Mi Fu (1051-1107) is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 35 x 44.1 centimeters. This work depicts a solitary kiosk before mountains in clouds. With several hoary pines, the scenery is succinct and elegant. Mountaintops are composed of layered horizontal "Mi dots" with moist brushwork for the magical wonders of mist in "Mi Family cloudy mountains." Above is a mounted inscription of poetry by the Song emperor Gaozong, and in the crevices of the lower left are two characters for "Mi Fu" that were apparently added later. Mi Fu (style name Yuanzhang, sobriquet Haiyue waishi) was originally from Taiyuan, Shanxi, but later moved to Xiangyang. He excelled at calligraphy and was a fine connoisseur, serving as Erudite of Painting and Calligraphy in the Xuanhe era under Emperor Huizong. His paintings are typically light and simple "Mi Family cloudy mountains."

“Buildings Among Mountains and Streams” by Yan Wengui (late 10th century-early 11th century)is an ink on silk hanging scroll, measuring 103.9 x 47.4 centimeters. Yan Wengui, native to Wuxing in Zhejiang, was a Painter-in-Attendance at the Painting Academy under Emperor Renzong. His landscapes for the most part feature huge peaks and lofty cliffs with buildings skillfully arranged, creating landscapes both delicate and pure. This painting depicts peaks and streams with a cascade and buildings among layered crags. The stone face on the left bears a signature for "Brushed by Hanlin Painter-in-Attendance Yan Wengui." Coarse, trembling lines render the outlines of peaks, the valleys in light ink creating a bright atmosphere. The brushwork is also fine and dense, reflecting Yan Wengui's style. The brushwork, though, is rounded and graceful, differing from the strong, angular style of other works associated with him. From perhaps the 12th or 13th century, this painting derives from Yan's style.

“Wintry Forests”, attributed to Li Cheng (916-967), is an ink on silk hanging scroll, measuring 180 x 104 centimeters. Among tree clusters is a winding stream with rock-crashing waves. Towering trees on both sides are enveloped in mists, this work focusing mainly on the foreground scenery. The trees feature powerful brushwork, the trunks with outlined circles to suggest knots and branches extending in various directions as in the Li Cheng and Guo Xi (Li-Guo) style. With washes of light ink for slopes, the brushwork is exquisite and varied. Stylistically, this is perhaps by a 13th-century northern artist imitating the Li-Guo style.

landscape by Fan Kuan

Travelers Among Mountains and Streams by Fan Kuan

“Travelers Among Mountains and Streams” painted by the Northern Song artist Fan Kuan in the early 11th century is one of China’s most famous paintings and arguable THE most famous landscape painting. Found at the National Palace Museum, Taipei, but usually in storage, its name in Chinese, literally means “Mountain and Water Painting”. It has influenced and been copied by generations of painters and still impresses viewers to this day with its sublime but awe-inspiring interpretation of nature. Madeleine Boucher wrote in the Art Genome Project: According to one story, Fan Kuan took to a journey deep into of the mountains to observe and learn from nature, and there learned how to convey the spirit of the mountains with his brush. [Source: Madeleine Boucher, Art Genome Project, June 24, 2014]

Fan Kuan (ca. 950-ca. 1031) had his ancestral home in Huayuan (modern Yaozhou District, Tongchuan City, Shaanxi Province). According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ Having the style name Zhongli (also reportedly named Zhongzheng with the style name Zhongli), he was easy-going by disposition and broad-minded. As a result, people in the Guanzhong region of Shaanxi, who used the term “kuan” (meaning “broad”) to describe someone deliberate, called him Fan Kuan. In painting, Fan first studied the styles of Li Cheng (916-967) and Jing Hao (fl. first half of the 10th c.), later spending years to observe Nature and develop his own approach. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

In “Travelers Among Mountains and Streams” in the National Palace Museum is the one most highly regarded and widely accepted as from his hand.In Fan’s division of that painting into a tripartite composition of foreground, middle, and distance, he skillfully pushed the monumental mountain range back and pulled the foreground up close.In doing so, he not only highlighted the miniscule proportion of the travelers but also created a dramatic contrast with the majestic peaks, forming an impressive sight as if before the viewer’s eyes.And hidden among the trees to the lower right side of this large scroll are two characters for Fan Kuan’s name that represent his signature.

“Another painting in the Museum collection, “Sitting Alone by a Stream,” though unsigned, is generally regarded as a fine early example in the Fan Kuan style.In this hanging scroll, the mountain peaks are dotted with thick forests, the outlines of the landscape forms rendered with heavy ink, and rocks jut out prominently in the foreground by the water.These characteristics can be traced back to Fan Kuan and are seen in his “Travelers Among Mountains and Streams” The texture strokes in “Sitting Alone by a Stream,” however, reveal more formulaic “small axe-cut” texture strokes rendered with a slanted brush, suggesting a date not far from the time of Li Tang (ca.1070-after 1150).

Fan Kuan began his career by imitating work by the painter Li Cheng (919-967) but later developed his own style, saying that nature was the only true teacher. His work became a model for painters that followed and he is still formidable and revered presence in Chinese history. His masterpiece “Travellers among Mountains and Streams” is regaded by some as the best Chinese painting ever. In 2004, Life Magazine rated Fan as 59th of the 100 most important people of the last millennium.

Guo Xi

Guo Xi (ca. 1020 -ca. 1090) was a famous landscape painter and court painter. He once wrote: "wonderfully lofty are these heavenly mountains, inexhaustible in their mystery. In order to grasp their creations, one must love them utterly and never cease wandering among them, storing impressions one by one in the heart." Guo Xi developed a strategy of depicting multiple perspectives called "the angle of totality." Because a painting is not a window, there is no need to imitate the mechanics of vision and view a scene from only one spot. Like most Song landscapists, Guo Xi used texture strokes to build up credible, three-dimensional forms. Strokes particular to his style include those on "cloud- resembling" rocks, and the "devil's face texture stroke," which is seen in the somewhat pock-marked surface of the larger rock forms. One of his most famous paintings,“Early Spring,” dated 1072, is in the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Guo Xi was the preeminent landscape painter of the late eleventh century. Although he continued the Li Cheng (919–967) idiom of "crab-claw" trees and "devil-face" rocks, Guo Xi's innovative brushwork and use of ink are rich, almost extravagant, in contrast to the earlier master's severe, spare style. [Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Guo Xi left significant writings on the philosophy and technique of landscape painting. On why landscapes were such an important subject in early Chinese painting, he wrote: "A virtuous man takes delight in landscapes so that in a rustic retreat he may nourish his nature, amid the carefree play of streams and rocks, he may take delight, that he might constantly meet in the country fishermen, woodcutters, and hermits, and see the soaring of cranes and hear the crying of monkeys. The din of the dusty world and the locked-in-ness of human habitations are what human nature habitually abhors; on the contrary, haze, mist, and the haunting spirits of the mountains are what the human nature seeks, and yet can rarely find. " /=\

Early Spring by Guo Xi

“Old Trees, Level Distance” is Northern Song dynasty (960-1127) painting by Guo Xi. Dated to 1080, it is a handscroll; ink and color on silk (35.6 centimeters × 104.4 centimeters).According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Old Trees, Level Distance” compares closely in brushwork and forms to “Early Spring.” In both paintings, landscape forms simultaneously emerge from and recede into a dense moisture-laden atmosphere: rocks and distant mountains are suggested by outlines, texture strokes, and ink washes that run into one another to create an impression of wet blurry surfaces. Guo Xi describes his technique in his painting treatise Linquan gaozhi (Lofty Ambitions in Forests and Streams): "After the outlines are made clear by dark ink strokes, use ink wash mixed with blue to retrace these outlines repeatedly so that, even if the ink outlines are clear, they appear always as if they had just come out of the mist and dew."

“Early Spring” by Guo Xi

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “”Early Spring”, done in 1072, is considered one of the great masterpieces of the Northern Song monumental landscape tradition. It is a rare example of an early painting executed by a court professional who signed and dated his work. Early Spring is characterized by ease and surety of strokes, executed quickly and having a tensile quality and structure. There are seven to eight layers of ink in softer areas, and the tonal range throughout is subtle. Broad outlines of boulders merge with background, showing a preference for integration.[Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Guo Xi made his reputation on his landscapes and pictures of dried trees, which are recognizable for their "crab-claw" branches. He painted "tall pines, lofty trees, winding streams, craggy cliffs, deep gorges, high peaks, and mountain ranges, at times cut off by clouds and mist, sometimes hidden in haze, representing them with a thousand variations and ten thousand forms."

Guo Xi is known to have prepared large-scale paintings for the decoration of several halls at court. Nevertheless, appreciation of his work at court varied greatly over time; it was said that after his death, his painting style had so fallen out of favor that a visitor to the court found someone using his old paintings as rags.

Guo Xi's paintings often contained three types of trees. The lesser, bending trees Guo Xi described anthropomorphically as holding one's creeds within oneself; the crouching, gnarled trees were seen analogous to an individual clinging to his own virtues; and the vertical trees were compared to those individuals who remain abreast of their environmental conditions (politics) and flourish.

A Thousand Li of River by Wang Ximeng

A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains by Wang Ximeng

"A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains" by Wang Ximeng (1096–1119) of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) is regarded as a landscape masterpiece and one greatest paintings in China. Painted in 1113 and now part of the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing, this ink and colors on silk handscroll is 1,191.5 centimeters long and 51.5 centimeters wide. Remarkably this very long painting was painted by the artist when he was only 17 and thus is the true work of a prodigy, [Source: Xu Lin, China.org.cn, November 8, 2011]

Xu Lin of China.org wrote: “Heavy ink strokes of black and other colors vividly depict mountains, lakes, villages, houses, bridges, ships pavilions and people. It is one of the largest paintings in Chinese history and has been described as one of the greatest works. Wang was one of the most renowned palace painters of the time. He became a student of the Imperial Painting Academy, and was taught personally by Emperor Huizong of Song. He finished this painting when he was only 18. Unfortunately, as a genius painter, he died very young in his 20s.

Marina Kochetkova wrote in DailyArt Magazine: Wang Ximeng (pronounced Wang Hsi Meng). was a prodigy and Emperor Huizong of Song supposedly taught the artist. Wang Ximeng painted A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains when he was only seventeen years old in 1113. He died several years later but he left one of the largest and most beautiful paintings in Chinese history. It is nearly twelve meters in length. [Source: Marina Kochetkova, DailyArt Magazine, June 18, 2021]

“The painting is a masterpiece of “blue-green landscape”. Azurite blue and malachite green dominate, and the artist also uses touches of pale brown. Wang Ximeng employs multiple perspectives to present a landscape. He shows us all the richness of the scenery with its green hills, temples, cottages, and bridges. The image is stunning in its sweeping scale, vivid colors, and minute details. If you zoom in, you can even see winding paths leading to secluded spots. With meticulous brushwork and superb technique, the artist expresses deep admiration for the grandeur of nature. In his painting, mountain formations rise and fall between a cloudless sky. Thus, Wang Ximeng opened up a new world, the landscape that you will never be tired of exploring.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/: Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated November 2021