SU SHI

Su Shi

Perhaps the best example of a scholar-official with strong interests in the arts is Su Shi (Su Dongpo, 1036-1101). Su Shi had a long career as a government official in the Northern Song. After performing exceptionally well in the examinations, Su Shi became something of a celebrity. Throughout his life he was a superb and prolific writer of both prose and poetry. Because he took strong stands on many controversial political issues of his day, he got into political trouble several times and was repeatedly banished from the capital. Twice he was exiled for his sharp criticisms of imperial policy. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

Su was one of the most noted poets of the Northern Song period. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Best known as a poet, Su was also an esteemed painter and calligrapher and theorist of the arts. He wrote glowingly of paintings done by scholars, who could imbue their paintings with ideas, making them much better than paintings that merely conveyed outward appearance, the sorts of paintings that professional painters made.”

Frederik Balfour of Bloomberg wrote: Su Shi, a household name in China, was an 11th-century scholar, statesman, poet, writer, calligrapher and artist, whose painting style has influenced virtually every Chinese painter ever since, according to Kim Yu, Christie’s international senior specialist of Chinese paintings. “He began an "aesthetic revolution" that departed from the highly detailed and meticulous academic Song dynasty works, which required months to complete. One of his most famous works, "Wood and Rock", is a simple and spontaneous work created for the artist’s personal pleasure and painted in one sitting. [Source: Frederik Balfour, Bloomberg, August 30, 2018]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Born in 1036, five emperors came to the throne during Su Shi's lifetime. Eleventh-century China, however, was a period of great political instability. The bitter rivalry between revisionist and conservative factions at court made a political career precarious. For Su Shi, known for his sharp wit and stubborn personality, it was even more difficult. However, the ups and downs of his life and career provided constant inspiration in his art and writing, for which he is so highly regarded by later generations.” It has now been almost 900 years since Su Shi passed away in 1101. Although his writings were once blacklisted, even destroyed, his genius could not be repressed. His poetry and writing have been reprinted, studied, and enjoyed by generations since. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TANG, SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY (A.D.960-1279) factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY (960-1279) ADVANCES factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY (960-1279) ECONOMICS AND AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com; GOVERNMENT, BUREAUCRACY, SCHOLAR-OFFICIALS AND EXAMS DURING THE SONG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; WANG ANSHI, HIS REFORMS AND HIS BATTLE WITH SIMA GUANG factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY CULTURE: TEA-HOUSE THEATER, POETRY AND CHEAP BOOKS factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY SONG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; LANDSCAPE, ANIMAL, RELIGIOUS AND FIGURE PAINTING factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY CERAMICS factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; San.beck.org san.beck.org ; Chinese Text Project ctext.org Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Word, Image, and Deed in the Life of Su Shi” (Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series) by Ronald C. Egan Amazon.com “Listening All Night to the Rain: Selected Poems of Su Dongpo (Su Shi)” by Su Dongpo, Jiann Amazon.com “Housing, Clothing, Cooking, from Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion 1250-1276" by Jacques Gernet Amazon.com ; “The Making of Song Dynasty History: Sources and Narratives, 960–1279 CE” by Charles Hartman Amazon.com “Chinese Urbanism: Urban Form and Life in the Tang-song Dynasties” by Jing Xie Amazon.com “The Reunification of China” by Peter Lorge Amazon.com “Ten States, Five Dynasties, One Great Emperor: How Emperor Taizu Unified China in the Song Dynasty” by Hung Hing Ming Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 5 Part One: The Five Dynasties and Sung China And Its Precursors, 907-1279 AD” by Denis Twitchett and Paul Jakov Smith Amazon.com; “Cambridge History of China, Vol. 5 Part 2 The Five Dynasties and Sung China, 960-1279 AD” by John W. Chaffee and Denis Twitchett Amazon.com; “China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty” by Charles Benn Amazon.com

Life of Su Shi (Su Dongpo)

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Su Shi, “also known as Zhizhang and Resident of Tong Po, is native of Meishan of Shichuan, and was an imperial scholar in the 2nd Year of Chia You (1057). His life may well be categorized into several distinctive stages. The first stage began in 1057 when he composed during the civil examinations the essay Hsing-shang Chung-hou Chih-chih Lun, a treatise on loyalty and generosity in punishments and rewards, which earned the chief examiner Ou-yang Hsiu's admiration. Decorated a chin-shih, Su Shi became a public official, and remained on the path of ascendance in the bureaucracy until his father's death, after which he returned to his hometown in Sze-chuan to observe a period of mourning. This stage is distinguished by Su's ambitious work for the government and his vibrant artistry and prolific discourses. Notable works from this time include twenty-five chin-tse's (policy essays) and Ssu-chi Lun, a work on the administration of government, which were characterized by progressive and critical incisiveness. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

“The second stage spanned from 1069 to 1079. After returning to the capital following the mourning of his father's death, Su Shi was arrested and jailed for a total of eleven years for his satirical poems criticizing the government's radical reform measures. It was during this time that Wang Anshi's New Policies were gaining prominence. To Emperor Shen-tsung Su presented a ten-thousand-word report in which he openly expressed his opposition to the reforms, which resulted in repeated demotions to insignificant provincial posts and exile to such places as Hangchou, Michou, Huchou and Hsuchou. Eventually he was banished to Huangchou. \=/

“The third stage of Su Shi’s life “is noted by the three years (1080-1083) that Su Shi spent in Huangchou, which represented a pivotal point in his life. Not only did he begin in earnest to consider the meaning of human existence, but also came to enjoy the pleasures of life from farming and writing. During this stage in life he wrote several of his most admired pieces, including Ch'ih-pi Fu (Ode to the Red Cliff), Han-shi T'ie (The Cold Food Observance), Nien-nu-chiao (Recalling Her Charms), Ting-feng-p'o (Stilling Wind and Waves), and Lin-chiang-hsien (Immortal by the River), as well as a great number of poems. These works seem to have come from the comfortable apposition of elegant artistry with the very ordinary events as experienced by one who was very much at peace with himself. \=/

“The fourth stage in Su Shi's life began in the year of 1085, when he was summoned to return to the capital. For the eight years that followed he served in the imperial court, during which he gained the favor of the Empress Dowager Kao, who was in effect ruling the country, and was appointed to the Hanlin Imperial Academy as an attendant academician. While his political career flourished, Su came up with very few thought-provocative works; apart from poetic inscriptions on paintings, his works largely comprised poetic compositions in the socializing vein. It appears that in the case of Su Shi the advancement in career had not been accompanied by comparable progress in artistry. \=/

“With the passing of Empress Dowager Kao and Emperor Che-tsung's assuming real power, Su Shi was obliged to go once more into the provinces. Accused of having spoken disrespectfully of the emperors, Su was banished to the island of Hainan, a region which was utterly barbarious and unknown. Rather than lamenting his diminishing fortunes, Su Shi derived greater strength and acquired broader perspectives from adversity. In fact, Su was able to articulate in his compositions complex and deep emotions, and to arrive at a new realm of creativity through his observation of common souls and ordinary things.” \=/

Political Career of Su Shi

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Su Shi (sobriquet Tzu-han, also known by the pen name of Tung-p'o chu-shih), by virtue of his prominence, was drawn into the power struggle between reformers led by Wang Anshi and conservative forces. On the one hand, his very nature had made it impossible for him to fall tamely in step with the reforms espoused by Wang; on the other, Su found it difficult to abide uncritically with the inclinations of the old guard. He was thus compelled to tread a circuitous path through the political intrigue of his time. Such experiences also elicited the complexity and diversity so characteristic of his philosophy and artistry. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

“Su's tumultuous career began around 1079, when he wrote a satirical poem on the New Policies promoted by Prime Minister Wang Anshi, who was infuriated and had Su arrested. Su served time in jail and was later released, but the following year he was banished to Huang-chou in the southern hinterlands. This proved to be a major turning point in his life. Beforehand, Su was a free and spirited personality, and his poetry was full of insight and energy. However, having barely escaped with his life and being banished to the harsh region of the south, he began to reflect on the beauty of nature and the meaning of life. In exile, he enjoyed the simple pleasures of farming and writing, taking joy in what life had to offer. In fact, many of his most popular works were done at the time. Though Su was later pardoned, he was never far from controversy. Even as an old man, he was banished to the furthest reaches of the land — Hainan Island in the South China Sea. The experience, however, only further enlightened him. Though pardoned once again, this time he did not make it back to court and died on the trip north. \=/

“In the factional struggles of the Northern Sung, Wang Anshi and Su Shi were in two opposing camps. Of differing personalities and political opinions, Wang was determined and intolerant while Su was straightforward and open-minded. With both serving at court, confrontation was inevitable. However, when Wang Anshi retired as prime minister and moved to Chin-ling, Su Shi had an opportunity to travel with him. Despite their differences, they looked back on old times and had a true meeting of the minds.” \=/

On a print of “Su Shi's Commentary on the Book of Documents, the National Palace Museum, Taipei says: ““Su Shi’s Commentary on the Book of Documents is one of three important writings of Su Shi, The Book of Change, Commentary on the Book of Documents, Essays on Analects of Confucius. It was finished when Su Shi was banished to Tan-chou in 1100. Sheet work printing was prevalent during Ming dynasty. Bookstore used subtle printing technique of overprinting plates to exalt printing quality and get more circulation. One of the period’s representative bookstore owner was Mr. Ling of Wu-hsing. He used black ink to print original article, red ink to print interpunction and comments on book. As Su Shi’s Commentary on the Book of Documents has red remark on head margin, big & sightly typeface of text, it was famous for the engraving edition form which easier to be read by readers. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Su Shi, the Poet-Artist-Calligrapher

Art by Su Shi

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Su Shi “holds a particularly revered position in Chinese literary history, and ranks as one of the Four Song Masters in calligraphy, while being the first scholar to create the scholar painting in Chinese painting history. He is one of the most important literary masters in the Northern Song period. Su had a very unstable career as a government official, and was exiled from court that resulted from the Wutai Poem Incident to Huangzhow in the 2nd Year of Yuan Feng (1079). This marked a turning point in his life and work, and the Former and Latter Odes to the Red Cliff were representative works from this period.” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Traditional critiques of Su Shi's calligraphy indicate that he often held the brush at an angle, producing characters that appeared somewhat abbreviated and thin. However, Su himself once wrote that "Plump and elegant as well as thin and tough (characters) both have their advantages." The characters here appear even and introverted, not abbreviated or unharmonious, making this a masterpiece of Su Shi's calligraphy. \=/

“Su Shi derived considerable joy throughout his life from the literary arts. However, the views that he expressed in his prose and poetry often got him into trouble. Even as an old man, it is said that he was exiled to the most remote southern locale of Hainan simply because of a line of his poetry was construed as mocking an enemy of his. Even in exile, however, Su Shi wrote to keep himself busy. \=/

“Su Shi's "The Cold Food Observance" is regarded an important work of poetry and calligraphy in the Northern Song period, calligraphy. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Su Shi's description in "The Cold Food Observance" ranges from the external illness of Su and the poor conditions of his surroundings in banishment to the remorse and conflict he felt at heart while living in exile, revealing a deep set of emotions. The calligraphy is therefore an attempt to transform the conditions in the poetry into concrete manifestations of imagery conveyed by the characters. As a result, the size of the characters gradually goes from small to large. The density also ranges from expansive to compact as the movement of the brush gradually quickened pace and became exaggerated. At times, the brushwork is light and other times heavy, sometimes fleeting and sometimes resigned. The ink so dark and thick that it seeped through the paper, with traces of brushwork between the strokes like silk threads echoing each other. The balance of the lines follows the angle of the characters, shifting to and fro and giving the entire work a complex and rich rhythm and beauty. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Funeral Oration In Memory of Huang Jidao,” by Su Shi is a regular script, handscroll written in 1087, work was the oration jointly signed by Su Shi and his brother Su Zhe in honour of their friend Huang Jidao. With a proper combination and natural variation of light and heavy strokes, the work conveys a respectful and endearing mood between the lines, showing profound literary accomplishment and excellent writing skills of the greatest writer and calligrapher of a generation. Funeral Oration In Memory of Huang Jidao has been in the collections of many people. Many of them left prefaces and postscripts on the scroll, such as Dong Qichang, Da Chongguang and so on. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Su Shi calligraphy

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “After Su Shi was exiled to Huang-chou, he came to be enlightened on the brevity and simple things of life. He also began to revere the figure of T'ao Yuan-ming, China's famous recluse-poet from 500 years earlier. Su felt that Tao's poetry possessed a sense of directness and beauty that was both natural and unadorned. Su therefore began composing poetry to the tune of Tao's verse. In 1092, while serving as magistrate of Yangchow, he composed "20 Poems on Drinking with T'ao." Later, after Su was banished to the far south, he further appreciated the poetry of T'ao Yuan-ming and was determined to collect all of the poems along with those by T'ao for a total of more than a hundred. The poetry of these two artists is not just a matter of similarity in form, but it represents the harmonious combination of two kindred spirits in one compilation. This Southern Sung imprint in four volumes, although it includes some later additions and repairs, is still an extremely precious early example. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Su Shi passed away on the 28th of July in 1101. While a good many of his works were either destroyed or banned by imperial edict, the fact remains that numerous editions and annotations of his complete works have been issued from the Sung Dynasty down to the present day. That his stirring poetic compositions and essays still touch the human heart nine hundred years after the words were written is testimony of the timelessness of his art. His outstanding calligraphy, too, is so very much admired today. \=/

“Of the early surviving annotated editions of Su Shi's poetry, one is by Shih Yuan-chih and the other by Wang Shih-p'eng. Shi's annotated edition is arranged chronologically, and Wang's by category. Both methods have their advantages and disadvantages. Shi's edition, however, enjoyed only limited circulation and became very rare. This text was not printed for wider audiences until the early Ch'ing dynasty (1644-1911), when Sung Lo-ts'ung bought a fragmentary Sung dynasty edition from a southern collector. He then asked Shao Ch'ang-heng and Li Pi-heng to edit and fill in the missing parts and had it published.

"Former Ode to the Red Cliff" by Su Shi

The "Former Ode to the Red Cliff" in the collection at the the National Palace Museum, Taipei was personally written by Su Shi” and is a “particularly rare masterpiece in literary and art. The Ode depicted Su and his friends travelling on a small boat to visit the Red Nose Cliff just outside Huangzhow city on July 16 in the 5th Year of Yuan Feng (1082), and recalled the Battle of Red Cliff when Sun Quan won victory over the Cao army during the times of the Three Kingdoms; through this Ode, Su expressed his views about the universe and life in general. \=/

“This Ode was written upon the invitation of his friend Fu Yao-yu (1024- 1091), and from the phrase "Shi composed this Ode last year" at the end of the scroll, one deduces that it was probably written during the 6th Year of Yuan Feng, when Su was 48 years of age. From Su's particular reminders of "living in fear of more troubles", and "by your love for me, you will hold this Ode in secrecy", one has a sense of Su's fear as a result of being implicated in the emperor's displeasure over writings. \=/

“The start of the scroll is damaged and is missing 36 characters, which were supplemented by Wen Zhengming (1470 ~ 1559) with annotations in small characters, although some scholars believe that the supplementations were actually written by Wen Peng. The entire scroll is composed in regular script, the characters broad and tightly written, the brushstrokes full and smooth, showing that Su had achieved perfect harmony between the elegant flow in the style of the Two Wang Masters that he learned from in his early years, and the more heavy simplicity in the style of Yen Zhenqing that he learned in his middle ages.” \=/

Ode on the Red Cliff

Red Cliff, Part I by Su Shi

The following short essay describes a small boat party on the Yangzi River. The boat-trip took place at Red Cliff, traditionally thought to be the place where Cao Cao a disastrous defeat at the hands of his enemies, Liu Bei and Sun Chuan, in 208. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

In “Red Cliff, Part,” Su Shi wrote: In the autumn of the year "jen-hsu" (1082), on the sixteenth day of the seventh month, I took some guests on an excursion by boat under the Red Cliff. A cool wind blew gently, without starting a ripple. I raised my cup to pledge the guests; and we chanted the Full Moon ode, and sang out the verse about the modest lady. After a while the moon came up above the hills to the east, and wandered between the Dipper and the Herdboy Star; a dewy whiteness spanned the river, merging the light on the water into the sky. We let the tiny reed drift on its course, over ten thousand acres of dissolving surface which streamed to the horizon, as though we were leaning on the void with the winds for chariot, on a journey none knew where, hovering above as though we had left the world of men behind us and risen as immortals on newly sprouted wings. [Source: “Red Cliff, Part I” by Su Shi (1036-1101), also known as Su Dongpo, “Anthology of Chinese Literature, Volume I: From Early Times to the Fourteenth Century,” edited by Cyril Birch (New York: Grove Press, 1965), 381-382 ]

“Soon when the wines we drank had made us merry, we sang this verse tapping the

gunwales:

Cinnamon oars in front, magnolia oars behind

Beat the transparent brightness, thrust upstream against flooding light.

So far, the one I yearn for,

The girl up there at the other end of the sky!

“One of the guests accompanied the song on a flute. The notes were like sobs, as though he were complaining, longing, weeping, accusing; the wavering resonance lingered, a thread of sound which did not snap off, till the dragons underwater danced in the black depths, and a widow wept in our lonely boat.

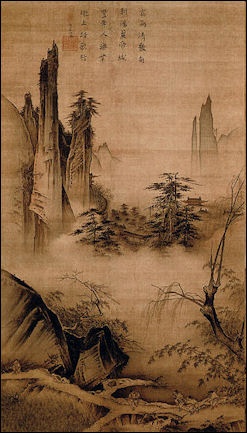

Japanese Red Cliff painting

“I solemnly straightened my lapels, sat up stiffly, and asked the guest: “Why do you play like this?” The guest answered: ‘Full moon, stars few Rooks and magpies fly south. …’ “Was it not Ts’ao Ts’ao who wrote this verse? Gazing toward Hsiak’ou in the west, Wu.ch’ang in the east, mountains and river winding around him, stifling in the close green … was it not here that Ts’ao Ts’ao was hemmed in by young Chou? At the time when he smote Ching.chou and came eastwards with the current down from Chiang.ling, his vessels were prow by stern for a thousand miles, his banners hid the sky; looking down on the river winecup in hand, composing his poem with lance slung crossways, truly he was the hero of his age, but where is he now? And what are you and I compared with him? Fishermen and woodcutters on the river’s isles, with fish and shrimp and deer for mates, riding a boat as shallow as a leaf, pouring each other drinks from bottlegourds; mayflies visiting between heaven and earth, infinitesimal grains in the vast sea, mourning the passing of our instant of life, envying the long river which never ends! Let me cling to a flying immortal and roam far off, and live forever with the full moon in my arms! But knowing that this art is not easily learned, I commit the fading echoes to the sad wind.”

“Have you really understood the water and the moon?” I said. “The one streams past so swiftly yet is never gone; the other for ever waxes and wanes yet finally has never grown nor diminished. For if you look at the aspect which changes, heaven and earth cannot last for one blink; but if you look at the aspect which is changeless, the worlds within and outside you are both inexhaustible, and what reasons have you to envy anything?

“Moreover, each thing between heaven and earth has its owner, and even one hair which is not mine I can never make part of me. Only the cool wind on the river, or the full moon in the mountains, caught by the ear becomes a sound, or met by the eye changes to colour; no one forbids me to make it mine, no limit is set to the use of it; this is the inexhaustible treasury of the creator of things, and you and I can share in the joy of it.” The guest smiled, consoled. We washed the cups and poured more wine. After the nuts and savouries were finished, and the wine.cups and dishes lay scattered around, we leaned pillowed back to back in the middle of the boat, and did not notice when the sky turned white in the east.”

Different Translation Red Cliff, Part I by Su Shi

Su Shi's Red Cliff poem illustrated on a vase

The following is a translation by Pauline Chen of the Former Ode, also known as the “First Prose Poem of the Red Cliffs”: “ In the autumn of 1082, on the 16th of the seventh month, Master Su and his guests sailed in a boat below the Red Cliffs. Clear wind blew gently, the water was calm. The boaters raised their wine and poured for each other, reciting “The Bright Moon” and singing “The Lovely One.” After a while, the moon rose above the eastern mountain, and hovered between the Dipper and the Cowherd star. White mist lay across the water; the light from the water reached the sky. They went where their tiny boat took them, floating on a thousand leagues of haze, in the vastness as if resting on emptiness and riding the wind, not knowing where they would stop, floating as if they had left the earth and stood alone, having turned into birds and become immortal. And so they drank and their joy reached its height, and they sang beating on the side of the boat. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“The song went:

Cassia oars and orchid paddles

Beat the illusory moon,

Rowing against the flow of streaming light.

From a great distance my heart

Yearns for my beloved at one end of the sky.

“Among the guests there was one who played the flute, and he played along with their song. The sound of his flute mourned, as if grieving as if loving, as if weeping as if reproaching. Its sound echoed and lingered, not breaking as if a silken thread. It set to dancing the dragon submerged in a deep crevice, and brought to tears the widow in the lonely boat.”

Rhyming with Tzu-yu's "Treading the Green" by Su Shi

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ Previous writers felt that Su Shi used the techniques for poetry when composing lyrics, but they failed to realize the genius in doing so. Sung dynasty lyrics after Su Shi were no longer the tunes that filled taverns and song houses. Instead, they could express melancholy and longing, becoming a medium for personal reflections and inner thoughts. This milestone in Sung poetry is the result of Su Shi's creative talent and virtue. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

Dancing and Singing Peasants by Ma Yuan

“Rhyming with Tzu-yu's "Treading the Green"” by Su Shi goes:

East wind stirs fine dust on the roads,

fine chance for strollers to enjoy the new spring.

Slack season—just right for roadside drinking,

grain still too short to be crushed by carriage wheels.

City people sick of walls around them,

clatter out at dawn and leave the whole town empty.

Songs and drums jar the hills, grass and trees shake;

picnic baskets strew the fields where crows pick them over.

Who draws a crowd there? A priest, he says,

blocking the way, selling charms and scowling:

“Good for silkworms—give you cocoons like water jugs!

Good for livestock—make your sheep big as deer!”

Passers.by aren’t sure they believe his words—

buy charms anyway to consecrate the spring.

The priest grabs their money, heads for a wine shop.

Dead drunk, he mutters, “My charms really work!”

“Treading the Green” refers to a day of picnics held in early spring. Su’s younger brother Tzu.Yu had written a poem describing the festival, and Su here adopts the same theme and rhymes for his own poem. The “priest” in line 9 may be either a Buddhist or Taoist priest. [Source: The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry,” edited and translated by Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), 297]

Su Shi Scroll Sells For Nearly US$60 Million

Su Shi’s “Wood and Rock” (1037-1101) is fifth the most expensive Chinese work of art ever sold at auction as of 2020. One of only two works by 11th-century artist known to exist, it was sold for US$59.7 million at at Christie’s, Hong in November 2018. Su Shi’s elegant handscroll with paintings and calligraphy is from the Song Dynasty (960–1279). Measuring 28 centimeters high, and 51 centimeters wide, this ink-on-paper work depicts a gnarled, leafless tree and a rock behind from which a few young bamboo shoots emerge. [Source: Mia Forbes thecollector.com, January 2, 2021]

Mia Forbes wrote in thecollector.com: One of the scholar officials charged with the administration of the Song Empire, Su Shi was a statesman and a diplomat as well as a great artist, a master of prose, an accomplished poet and a fine calligrapher. It is partly for the multi-faceted and highly influential nature of his career that his remaining artwork is so valuable. ‘Wood and Rock’ is an ink painting on a handscroll over five meters in length. It depicts a strangely shaped rock and tree, which together resemble a living creature. Su Shi’s painting is complemented by calligraphy by several other artists and calligraphers of the Song Dynasty, including the renowned Mi Fu. Their words reflect on the meaning of the image, speaking of the passing of time, the power of nature and force of Tao.

Frederik Balfour of Bloomberg wrote: “The work is only one of two known scrolls produced by Su Shi, and the first to ever appear at auction, Christie’s said. The other resides in the National Palace Museum in Taiwan. "This is simply the best Chinese painting you could possibly get," said Jonathan Stone, co-chairman of Christie’s Asian Art department, who likened the piece’s significance and rarity to that of "Salvator Mundi" by Leonardo Da Vinci. "In the purely market sense, there is comparability." [Source: Frederik Balfour, Bloomberg, August 30, 2018]

Su Shi, a household name in China, was an 11th-century scholar, statesman, poet, writer, calligrapher and artist, whose painting style has influenced virtually every Chinese painter ever since, according to Kim Yu, Christie’s international senior specialist of Chinese paintings. “He began an "aesthetic revolution" that departed from the highly detailed and meticulous academic Song dynasty works, which required months to complete. Su Shi’s "Wood and Rock" is a simple and spontaneous work created for the artist’s personal pleasure and painted in one sitting, Yu said.

“Between the 11th and 16th century, four "colophons," or commentaries by famous calligraphers were added to the scroll, which now is more than six feet long. The scroll also contains 41 collector’s seals which provide an unimpeachable record of its ownership provenance. “Like Da Vinci, Su Shi was a "renaissance man," though long before the Western concept came into existence several centuries later, Stone said. "I like to think of Leonardo as a Western Su Shi, rather than Su Shi as a Chinese Leonardo. We shouldn’t look at things through an Atlantic lens," he said. The former owner was “a Japanese family that acquired it from a Chinese dealer in 1937. They contacted Christie’s about selling it after the success of a $263 million sale of Chinese artworks from the Fujita Museum it held in New York in March 2017.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021