SONG DYNASTY BUREAUCRACY

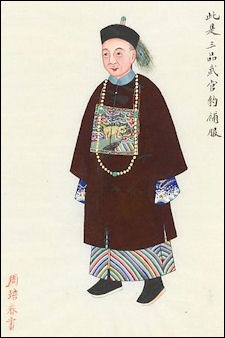

Chinese official

“The founders of the Song dynasty built an effective centralized bureaucracy staffed with civilian scholar-officials. Regional military governors and their supporters were replaced by centrally appointed officials. This system of civilian rule led to a greater concentration of power in the emperor and his palace bureaucracy than had been achieved in the previous dynasties. The northern Song dynasty emphasized "orderly and virtuous governance, achieved largely through efficient bureaucracy staffed by mandarins who passed the rigorous state examinations...the revival of Confucian teaching gave a particularly strong moral flavor to the dynasty."

Song rule featured a bureaucratic ruling class that derived its legitimacy from philosophical orthodoxy and an economy that involved an increasingly active free peasantry interacting with large urban commercial, manufacturing and administrative centers. As was true with the dynasties the Song Dynasty was essentially ruled by an elite bureaucracy chosen through competitive examinations on classic Confucian texts. Some 20,000 mandarins were responsible for governing an empire with more than 100 million people. Progress was hampered somewhat by strong central control. Fearing loss of authority, the bureaucracies reigned in the power of merchants with strict regulations.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The Song emperor, like the rulers of the transition period, had gained the throne by his personal abilities as military leader; in fact, he had been made emperor by his soldiers as had happened to so many emperors in later Imperial Rome. For the next 300 years we observe a change in the position of the emperor. On the one hand, if he was active and intelligent enough, he exercised much more personal influence than the rulers of the Middle Ages. On the other hand, at the same time, the emperors were much closer to their ministers as before. We hear of ministers who patted the ruler on the shoulders when they retired from an audience; another one fell asleep on the emperor's knee and was not punished for this familiarity. The emperor was called "kuan-chia" (Administrator) and even called himself so. And in the early twelfth century an emperor stated "I do not regard the empire as my personal property; my job is to guide the people". Financially-minded as the Song dynasty was, the cost of the operation of the palace was calculated, so that the emperor had a budget: in 1068 the salaries of all officials in the capital amounted to 40,000 strings of money per month, the armies 100,000, and the emperor's ordinary monthly budget was 70,000 strings. For festivals, imperial birthdays, weddings and burials extra allowances were made. Thus, the Song rulers may be called "moderate absolutists" and not despots. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“One of the first acts of the new Song emperor, in 963, was a fundamental reorganization of the administration of the country. The old system of a civil administration and a military administration independent of it was brought to an end and the whole administration of the country placed in the hands of civil officials. The gentry welcomed this measure and gave it full support, because it enabled the influence of the gentry to grow and removed the fear of competition from the military, some of whom did not belong by birth to the gentry.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TANG, SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY (A.D.960-1279) factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY (960-1279) ADVANCES factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY (960-1279) ECONOMICS AND AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com; SU SHI (SU DONGPO)—THE QUINTESSENTIAL SCHOLAR-OFFICIAL-POET factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; WANG ANSHI, HIS REFORMS AND HIS BATTLE WITH SIMA GUANG factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY CULTURE: TEA-HOUSE THEATER, POETRY AND CHEAP BOOKS factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY SONG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; LANDSCAPE, ANIMAL, RELIGIOUS AND FIGURE PAINTING factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY CERAMICS factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; San.beck.org san.beck.org ; Chinese Text Project ctext.org Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Wang Anshi and Song Poetic Culture” (Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series) by Xiaoshan Yang Amazon.com “His Stubbornship: Prime Minister Wang Anshi (1021--1086), Reformer and Poet” by Jonathan Pease and Portland State University Amazon.com ;“The Reunification of China” by Peter Lorge Amazon.com “The Making of Song Dynasty History: Sources and Narratives, 960–1279 CE” by Charles Hartman Amazon.com “Ten States, Five Dynasties, One Great Emperor: How Emperor Taizu Unified China in the Song Dynasty” by Hung Hing Ming Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 5 Part One: The Five Dynasties and Sung China And Its Precursors, 907-1279 AD” by Denis Twitchett and Paul Jakov Smith Amazon.com; “Cambridge History of China, Vol. 5 Part 2 The Five Dynasties and Sung China, 960-1279 AD” by John W. Chaffee and Denis Twitchett Amazon.com; “China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty” by Charles Benn Amazon.com; “Chinese Urbanism: Urban Form and Life in the Tang-song Dynasties” by Jing Xie Amazon.com

Scholar-Officials During the Song Dynasty

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Song period saw the full flowering of one of the most distinctive features of Chinese civilization — the scholar-official class certified through highly competitive civil service examinations. Most scholars came from the landholding class, but they acquired prestige from their learning and political clout by serving in office. In a society in which most people were illiterate, scholar-officials stood out by virtue of their reading and writing skills. Their Confucian education encouraged them to aspire for government service, but also to speak up when they thought others were pursuing the wrong course, making them courageous critics of power. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

“The officials of the Song dynasty approached the task of government with the inspiration of a reinvigorated Confucianism, which historians refer to as “Neo-Confucianism.” As with any group of scholars and officials, different individuals had different understandings of just what concrete measures would best realize the moral ideals articulated in the Analects and Mencius. Such disagreements could be quite serious and could make or unmake careers. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Success as a scholar-official was often defined in terms of knowledge on the Five Confucian Classics — 1) Classic of Poetry (Shijing); 2) Classic of History (Shujing); 3) Classic of Changes (Yijing); 4) Record of Rites (Liji); and 5) Chronicles of the Spring and Autumn Period (Chunqiu)— and The Four Books — 1) The Great Learning (Daxue); 2) The Doctrine of the Mean (Zhongyong); 3) The Analects of Confucius (Lunyu); and 4) The Mencius (Mengzi).

Neo-Confucianism in the Song Period

Neo-Confucianist Zhou Dunyi

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ There was a vigorous revival of Confucianism in the Song period. Confucian teachings were central to the civil service examination system, the identity of the scholar-official class, the family system, and political discourse. Confucianism had naturally changed over the centuries since the time of Confucius (ca. 500 B.C.). Confucius’s own teachings, recorded by his followers in “The Analects”, were still a central element, as were the texts that came to be called the Confucian classics, which included early poetry, historical records, moral and ritual injunctions, and a divination manual. But the issues stressed by Confucian teachers changed as Confucianism became closely associated with the state from about 100 B.C. on, and as it had to face competition from Buddhism, from the second century CE onward. Confucian teachers responded to the challenge of Buddhist metaphysics by developing their own account of the natural and human world. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

“With roots in the late Tang dynasty, the Confucian revival flourished in the Northern and Southern Song periods and continued in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties that followed. The revived Confucianism of the Song period (often called Neo-Confucianism) emphasized self-cultivation as a path not only to self-fulfillment but to the formation of a virtuous and harmonious society and state.

“The revival of Confucianism in Song times was accomplished by teachers and scholar-officials who gave Confucian teachings new relevance. Scholar-officials of the Song such as Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) and Sima Guang (1019-1086) provided compelling examples of the man who put service to the state above his personal interest.”

Song Dynasty Scholar-Official Examinations

Imperial exam

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Since the Sui Dynasty (581-617), it had been possible to become a government official by passing a series of written examinations. It was only in the Song, however, that the examination system came to be considered the normal ladder to success. From the point of view of the early Song emperors, the purpose of the civil service examinations was to draw men with literary educations into the government to counter the dominance of military men. So long as the system identified men who would make good officials, it did not matter much if some talented people were missed. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “ By the time of the Song, the civil service examination system had become so central to the Chinese state that it was, in many was, the cultural focus of all who aspired to success. Even the growing merchant class, which was, by policy, banned from participating in the exams because their profession, based on self-serving “greed” for profit, was considered intrinsically immoral, looked for ways to have some of their sons shed the merchant class designation in order that the family could become members of the most prestigious class in society: the official class. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

According to Asia for Educators: “In Song times exam success came to carry such prestige that the number of men entering each competition grew steadily, from fewer than 30,000 early in the dynasty, to about 400,000 by the dynasty’s end. Because the number of available posts did not change, a candidate’s chances of passing plummeted, reaching as low as one in 333 in some prefectures. Men often took the examinations several times, and were on average a little over 30 when they succeeded. The great majority of those who devoted years to preparing for the exams, however, never became officials.”

Song Dynasty Examination System

ranking list of the Jinshi exam

Dr. Eno wrote: “Although the intricacies of the examination system were endless, its basic structure was simple. Throughout the period from about 589 to 1905, the central imperial government held massive exams at the various capitals of China every three years. Those who performed best on these exams earned the right to receive government positions; the specific position was determined through a combination of exam scores, personal influence, and available openings. To select the thousands of young men (and men only) who could compete for these exams, lower level tests were administered annually at provincial and county levels. The aspiring young man could expect to spend several years moving upward through this pyramid of exams..that is, assuming that he was successful at the lower levels: most were not. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: ““From the point of view of those taking the examinations fairness was crucial. They wanted to be assured that everyone was given an equal chance and the examiners did not favor those they knew. To increase their confidence in the objectivity of the examiners, the Song government decided to replace candidates’ names with numbers and had clerks recopy each exam so that the handwriting could not be recognized. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

According to Asia for Educators: “Scholars in and out of the government regularly debated what should be asked on the examinations, but everyone agreed that one element should be command of Confucian texts. Candidates were usually asked to discuss policy issues, but the examinations tested general education more than knowledge of government laws and regulations. Candidates even had to write poetry in specified forms. To prepare for the examinations, men would memorize the Confucian classics in order to be able to recognize even the most obscure passages.

Preparation for the Scholar-Official Examinations

Dr. Eno wrote: “Preparation for the tests began at an early age and could continue for many years; in some cases, men spent their entire lives attempting to pass the exams (which could be taken any number of times). Successful candidates were rewarded with great prestige. Their families could boast that they belonged to the sole recognized nation-wide elite, and were permitted to fly a special flag at the gates of their family compounds. They could expect that their successful son would bring to the family all the benefits that Confucian education, public service, and deeply entrenched customs of bribery could provide. Although the examinations were open to any adult male, regardless of birth, in practice families whose members had already achieved high rank through the examinations were at a tremendous advantage in preparing the next generation for success. It was such families who usually possessed the resources that allowed them to excuse their children from all economic contributions to the household in order that they might spend a dozen years or more devoting themselves solely to the study of examination texts. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“There were a number of different types of examination tracks open to young men. The most important was the Confucian civil service examination, which gave men access to the highest level of government posts. These exams were based on a thorough mastery of the extensive corpus of Confucian classical texts, with their voluminous commentaries, of political essays composed by exemplary Confucians of the post-Classical era, and of the arts of poetry, calligraphy, and essay composition that marked one as a cultivated member of the Chinese intellectual elite. /+/

“The intensity of this educational process can be suggested by a quantitative measure concerning only the matter of Confucian classical texts. In addition to a very wide knowledge of the texts and their commentaries, exam candidates were expected to know a certain core group of these texts by heart. The texts that needed to be memorized included the following group, listed below with the total number of words, or Chinese characters, that they include:

The Analects.................................. 11,705

The Mencius.................................. 34,685

The Yijing..................................... 24,107

The Book of Documents................. 25,700

The Book of Songs........................ 39,234

The Book of Rites........................... 99,010

The Zuozhuan................................ 196,845

The total comes to well over 400,000 words, roughly the equivalent of memorizing a book of 1,000 pages word-perfect. And this was just for starters! A never ending stream of commentaries, histories, poetry and so forth would demand unceasing attention for all the years of a student’s youth, and preparation for the highly artificial literary styles demanded by ossified examination formats ensured that when a student wasn’t memorizing texts, he was trying to master poetic rhyme schemes or baroque essay formats that would please the critical eye of future examiners.” /+/

Exam takers

Social Consequences of the Exam Curriculum

Dr. Eno wrote: “ The imperative of rote learning that permeated the education of Chinese youths was symptomatic of the authoritarian character of the entire system of Confucian education. Although students read the “Analects” of Confucius and heard him state plainly there that he was not “one who studied much and memorized what he had studied,” and saw that Confucius challenged the legitimacy of virtually every power holder of his day, the overall thrust of Confucianism, as presented to young boys, stressed the primacy of the Three Bonds: obedience to father, elders, and rulers. This was a primary lesson instilled in every child aspiring to become a member of the ruling class of China, and although a significant number of men were able to overcome this call to political docility in their maturity, the overall cast it leant to the bureaucratic government of China was a high tolerance for imperial autocracy and fear of innovation. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“This tendency undermined one of the most progressive features of the examination system..the fact that the institution of government appointment through examination made access to wealth and power dependent upon intellectual merit rather than on the whim of the ruler or personal connections at court. The government system of China is often referred to as a “meritocracy,” and this is one of China’s most celebrated glories. However, the intellectual “merit” that earned young men promotion was not necessarily the type of creative or independent achievement that we would tend to deem appropriate for the highest levels of public responsibility. /+/

“The intensity of textual study that was required to rise from the lowest educational levels to candidacy for the examinations was so great that it formed an effective barrier to most children. In some cases, this was simply a matter of intellectual talent or an ability to settle down and study hour after hour, year after year (not a quality we associate with children). More often, it was simply a matter of economics. Only a small percentage of the households of China could afford to spare a son to full.time study for the entire period of his life at home. This fact worked against another of the most progressive features of the examination system..its openness. In theory, with only a few exceptions (such as the exclusion of merchant families from candidacy during certain periods), social mobility through competitive examination was available to the sons of all families, down to the lowliest peasants. While it is true that talented sons of impoverished families somehow scrimped their way through to expertise and high rank frequently enough to maintain the meaningfulness of the exam system’s egalitarian promise, the great majority of successful candidates always came from privileged families in the wealthiest regions of China. /+/

Exams and the Confucian Esprit de Corps

Dr. Eno wrote: “ One of the unique features of Chinese society that resulted from the exam system was the fact that members of the ruling bureaucracy from the sixth century on shared a common experience of great intensity that formed an important bond among them. While in many traditional societies, members of a single generation might share certain sorts of military training or experiences, or in smaller social groups might undergo some other type of rite of initiation, China was unique among traditional cultures in subjecting its large governing elite to an intellectual initiation such as the exam system. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Every three years, young men of promise would flock to the capital city, find lodging in that sophisticated and strange place, and encounter hundreds of other young men from all parts of the empire similarly displaced in the hope of lifelong advancement. During the period leading up to the exams, candidates, who were often on their own for the first time in their lives, would form intense friendships, friendships which might later form a network of government contacts. Many features of Chinese political history are best explained only after one has examined lists of triennial examination candidates and discovered which political actors were linked by comradeship dating to their exam days. Moreover, exam graduates also formed important relationships with their examiners, and men who performed outstandingly on the exams could expect that their examiners would become lifelong patrons who would serve as surrogate fathers within the Confucian bureaucracy. /+/

Exam cells

“The function of the exams as a socializing experience was enhanced by the exhausting nature of the metropolitan tests. The entire process stretched over eight days, and was permeated by elaborate ritual ceremonies. The examinees spent days at a time locked in tiny examination cells which stretched over several acres in prison-like rows, and were expected to write all day and all night, squinting under the light of their cubicle candles. /+/

“Given the stress of these terrible conditions, a rich body of folklore grew around the exams, reinforcing their impact upon society and the men who had to endure them. Candidates who entered their cells had heard how the ghosts of failed candidates haunted the testing grounds in the night, and it was not unknown for men’s courage to break; sometimes a hapless candidate would be found hanging in his cell at dawn, his undistinguished exam paper left incomplete. /+/

Education and Governmental Responsibility

Dr. Eno wrote: “ Perhaps the greatest irony of the civil service examination system in China is that in many respects, despite the praiseworthy principle of appointment by competitive examination, the system was defective because the exams tested students for the wrong skills. It was a fundamental tenet of the time that mastery of Confucian moral texts, of poetic forms, and of the rhetoric of canonical commentary uniquely equipped a man to govern others. To us, it seems self-evident that this is not true. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Successful graduates of the exam system faced certain immediate problems to which they were ill suited to respond. Graduates were often posted to low level positions in the provinces where they assumed duties at the level of the county magistrate. There, they were responsible for such duties as tax collection, water conservation, agricultural enhancement, legal administration, and management of their own county offices, called "yamen". Typically, they faced certain handicaps. First of all, their jurisdictions generally extended over populations of perhaps forty to fifty thousand people, and they were supplied with no assistance from the central government. Magistrates were responsible for hiring "yamen" staff from local people. Because there was a “rule of avoidance” that ensured that no official would ever be appointed to a post in his home district (to avoid problems of favoritism), a new officer from the capital would be entirely unfamiliar with the population from which he had to select his assistants. Frequently, when young men were posted far from their home counties, they were not even able to understand the local dialects of the people they governed! Moreover, the budget of a magistrate was a very limited one..his salary was small and he was provided with virtually no discretionary funds. /+/

Chinese official weighing out rice for prisoners

“Basically, young men fresh from their Confucian studies were completely untrained in the skills that would allow them to succeed under such conditions unless they had received informal instruction from family members or acquaintances who had been immersed in government. It was quite common for such men to govern incompetently. Some resorted to brutal authoritarian measures, others exhausted themselves issuing moral proclamations urging their people to behave properly (not a very effective strategy). Most often, magistrates fell under the influence of powerful local families, who provided them with “officers” who were skilled in using coercion to extract taxes from peasants and confessions from “criminals.” By relying on such local bullies, a magistrate could ensure that he could forward to the central government the revenues the emperor demanded and that he could submit records of court proceedings demonstrating his sagely ability to bring the guilty to justice and keep order in his district. Inevitably, such patterns of conduct also involved habits of bribery and other forms of corruption that were endemic in the Chinese political system (and remain so today). /+/

“Periodically, there were reform initiatives that proposed to make the contents of the exams more relevant to the practical skills necessary for government. But these movements were rarely successful. The men who occupied high office and served as the examiners of the next generation had invested their entire identities in the education of their youth..they were not likely to approve of any radical change in standards or content to the exams. In most cases, the most revolutionary changes merely involved the authorization of a more “modern” or pragmatically oriented set of commentaries to the Confucian classics than those that had been employed previously. While in some cases this might have allowed examiners to give added weight to answers that suggested some grasp of the intricacies of practical governance, this was not always the result. The fourteenth century certification of the commentaries of the great Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi’s as orthodox resulted in the opposite result. Zhu Xi was a brilliant metaphysician..his theories of the cosmos and its relation to man’s ethical tendencies represent a wonderful example of philosophical imagination – but when successful candidates sought to apply Zhu’s cosmic theories of Heavenly Principle, material force, and the moral intuitions of the sage heart to the problems of tax collection, flood control, and militia organization, they sometimes found that he was a little sketchy on the details. /+/

Famous Song Dynasty Scholar-Officials

Song officials such as Fan Zhongyan (989-1052), Su Shi (1037-1101, also known by his pen name, Su Dongpo), and Wang Anshi (1021-1086) worked to apply Confucian principles to the practical tasks of governing. Su Shi had a long career as a government official in the Northern Song. Twice he was exiled for his sharp criticisms of imperial policy. Su is also one of the most noted poets of the Northern Song period. Fan Zhongyan was a prominent statesman, strategist, educator, and writer of the Northern Song Dynasty.

Wang Anshi

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Wang Anshi was a noted scholar and official. He distinguished himself during a long term of service as a country magistrate. In 1068, the young Shenzong Emperor (r. 1068.1085), then twenty years old, appointed Wang Anshi as Chief Councilor and charged him with carrying out a thorough-going reform of the empire’s finances, administration, education, and military. The intention was to address a serious problem: declining tax revenue and mounting government expenses, including the huge and growing cost of maintaining a large standing army. Wang Anshi proposed a series of reforms, including the “Crop Loans Measure” discussed in the memorial below. The reforms were carried out. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

The Southern Song philosopher and scholar Zhu Xi (1130-1200) was very influential in the Confucian revival of the time. Known for his synthesis of Neo-Confucian philosophy, he wrote commentaries to the Four Books of the Confucian tradition and emphasized the Four Books as a basis for Confucian learning and the civil service examinations. Sima Guang (1019-1086) was a historian and high-ranking official of the Northern Song best known compiling his monumental 294-chapter history of China, entitled Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance (Zizhi tongjian).

See Separate Article WANG ANSHI, HIS REFORMS AND HIS BATTLE WITH SIMA GUANG

Book: “A Compilation of Anecdotes of Sung Personalities,” translated by Chu Djang and Jane C. Djang (St. John’s University Press, 1989)]

Zhu Xi

Zhu Xi (1130-1200) was the most influential Neo-Confucian philosopher. His synthesis of Confucian thought and Buddhist, Taoist, and other ideas into Neo-Confucianism became the official imperial ideology from late Song times to the late nineteenth century. As incorporated into the examination system, Zhu Xi's philosophy evolved into a rigid official creed, which stressed the one-sided obligations of obedience and compliance of subject to ruler, child to father, wife to husband, and younger brother to elder brother. The effect was to inhibit the societal development of premodern China, resulting both in many generations of political, social, and spiritual stability and in a slowness of cultural and institutional change up to the nineteenth century. Neo-Confucian doctrines also came to play the dominant role in the intellectual life of Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. [Source: Library of Congress]

Zhu Xi was born in Nanping, Fujian. He later resided in Kaoting, Jianyang in Fujian. His ancestors came from Wuyuan, Jiangxi. He had style names Yuanhui and Zhonghui; the sobriquets Huian, Huiweng, and Tun- weng. Later in his life he was also referred to as Master Ziyang, the Sick Man of Cangzhou and Master Kaoting. He is respectfully referred to by posterity as "Zhuzi". Zhu Xi was very influential in the Confucian revival of his time. He spent his entire career pursuing an ambition of establishing a new order in China and wrote commentaries to the Four Books of the Confucian tradition and emphasized the Four Books as a basis for Confucian learning and the civil service examinations. Zhu Xi was also active in the theory and practice of education and in the compiling of a practical manual of family ritual. Zhu Xi’s synthesis was accepted as the orthodox interpretation of Confucianism in the later Ming and Qing dynasties, as well as in other East Asian countries.

Zhu Xi

During his lifetime Zhu Xi studied a great variety of fields; in addition to Confucianism, he had also written extensively on philosophy, ethics, history, political science, philology and philological theory. His youngest son, Zhu Zai, compiled his treatises and edited them to become the The Literary Collection of Zhu Xi., The Literary Collection of Zhu Xi comprises of 100 volumes and was compiled during the late of Ningzong Emperor and the early of Lizong Emperor.

Dr. Eno wrote: “Zhu Xi was a brilliant metaphysician..his theories of the cosmos and its relation to man’s ethical tendencies represent a wonderful example of philosophical imagination – but when successful candidates sought to apply Zhu’s cosmic theories of Heavenly Principle, material force, and the moral intuitions of the sage heart to the problems of tax collection, flood control, and militia organization, they sometimes found that he was a little sketchy on the details.” [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

National Palace Museum, Taipei description of the calligraphy by Zhu Xi in the “Letter on Government Affairs” (album leaf, ink on paper, 33.3 x 47.8 centimeters): Zhu Xi was excited to hear that Emperor Xiaozong in his later years wanted to recruit Neo-Confucian scholars to reform the government, but unfortunately the emperor passed away not long after reforms had begun, bringing them to an abrupt end. \=/ This letter was written with great speed and force, being composed on Zhu Xi's way to the capital after leaving office as Administrator of Tanzhou (modern Changsha, Hunan) in the eighth month of 1194. The contents are directed to a subordinate in dealing with government matters in Tanzhou. The first passage mentions Zhu's sorrow at "national mourning," referring to the death of Xiaozong in the sixth month of that year. But with Emperor Ningzong assuming the throne in the seventh month, Zhu had the opportunity to teach at court, immediately bringing him great joy. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Four Books of Zhu Xi

Zhu Xi's Commentaries on the Four Classics

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ The Four Books, with a Collection of Comments and comprises of one volume of "Chapters from The Great Learning", ten volumes of "Compilations of The Analects of Confucius", seven volumes of "Compilations of Mencius", and one volume of "Chapters from Doctrine of the Mean". [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“The Great Learning and Doctrine of the Mean were originally chapters from The Classics of Rites, and were singled out and separately discussed only from Song Dynasty. The title The Four Books was given by Zhu Xi, who separated the classics from the biographies in The Great Learning, and also renumbered the chapters and supplemented missing sections from Doctrine of the Mean, referring to them as "Chapters". \=/

“The Analects of Confucius and Mencius were compilations of the various masters, and were therefore referred to as "Compilations". The original compilation placed the greatest emphasis on The Great Learning, followed by The Analects of Confucius, and then Mencius and Doctrine of the Mean, indicating the order of learning. The Four Books, with a Collection of Comments reflects Zhu Xi's scholarly style, carefully considering each and every sentence, referring to and combining accounts by other scholars, placing emphasis on elucidation of logic and annotating his own opinions. The main theme of Chapters from The Great Learning is an "inquiring mind", describing the learning process of "finding the righteous path in everything". \=/

“Zhu Xi had devoted his life to Compilations of the Four Books, and not only has a unique position and influence in the Neo-Confucianism, he had also included Mencius as one of the classics. Together with The Analects of Confucius, Erya: a Dictionary, The Book of Filial Piety and the "Nine Classics" from the Tang Dynasty, these now form the official "Thirteen Classics. The Four Books was a milestone in the history of Chinese literary classics.” \=/

Three Perfections and Scholar-Official Painting

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ The life of the educated man involved more than study for the civil service examinations and service in office. Many took to refined pursuits such as collecting antiques or old books and practicing the arts — especially poetry writing, calligraphy, and painting (“the three perfections”). For many individuals these interests overshadowed any philosophical, political, or economic concerns; others found in them occasional outlets for creative activity and aesthetic pleasure. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

Su Shi

In the Song period the engagement of the elite with the arts led to extraordinary achievement in calligraphy and painting, especially landscape painting. But even more people were involved as connoisseurs. A large share of the informal social life of upper-class men was centered on these refined pastimes, as they gathered to compose or criticize poetry, to view each other’s treasures, or to patronize young talents.

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “During the middle of the Northern Song scholars began to take up painting as one of the arts of the gentleman, viewing it as comparable to poetry and calligraphy as means for self expression. Brushwork in painting, by analogy to brushwork in calligraphy, was believed to express a person's moral character. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“The scholars who took up painting generally preferred to use more individualistic and less refined styles of brushwork. These styles were relatively easier to master by those already familiar with the brush from calligraphy, and did not require the years of exacting training needed to succeed as a professional or court artist. /=\

“The eminent poet and statesman Su Shi (1037-1101) explicitly rejected the attempt to capture appearance as beneath the scholar. Paintings should be understated, not flashy. His painting of Rock and Old Tree, executed with a dry brush, exhibits rough qualities and does not aim at pleasure. The painting is more akin to an exercise aiming to improve and develop calligraphic skill than the sorts of paintings done by contemporary court painters. Emphasizing subjectivity, Su Shi said that painting and poetry share a single goal, that of effortless skill. /=\

“Scholar painters were not necessarily amateur painters, and many scholars painted in highly polished styles. This was particularly true in the case of paintings of people and animals, where scholar-painters developed the use of the thin line drawing but did not in any real sense avoid "form likeness" or strive for awkwardness, the way landscapists often did. One of the first literati to excel as a painter of people and animals was Li Konglin in the late Northern Song. A friend of Su Shi and other eminent men of the period, he also painted landscapes and collected both paintings and ancient bronzes and jades. Figures done with a thin line, rather than a modulated one, were considered plainer and more suitable for scholar painters.” /=\

Fan Zhongyan: Prominent Scholar-Official-Poet

Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) was a prominent Chinese statesman, strategist, educator and writer of the Northern Song Dynasty. Wang Ping wrote on CCTV.com: “He believed that the shortage of talented people was the major problem of the country, so education should be developed vigorously to train such people. Wherever he went, he made painstaking efforts to run schools. He founded the well-known Suzhou Prefectural School. Thanks to his pioneering endeavours, a good many talented scholars came to the fore during the Song and the ensuing dynasties. [Source:Wang Ping, CCTV.com, April 6, 2004 ~]

“Fan Zhongyan was one of the outstanding writers of poetry and prose during the Song Dynasty. "On Yueyang Tower" was his representative work. The well-known essay was not an elaborate portrayal of the tower alone. It was a depiction of the vast scene of the surrounding Dongting Lake, then a description of the mentality of banished officials and poets, and finally an elevation to a higher plane of philosophy. "One should be the first to bear hardships and the last to enjoy comforts," is a well-known remark by made Fan Zhongyan that has often been repeated over the centuries. ~

Fan Zhongyan

“Fan Zhongyan was born in Wuxian County, Suzhou in present-day Jiangsu Province in 989. When he was a child, his father died and his mother married another man. He was poor, but he learned diligently. At the age of 26, he became a successful candidate in the highest imperial examination and began his long official career. He was always anxious about the rise and fall of the nation and the joys and sorrows of the people.~

“Xixi, Taizhou was a small town on the coast of Jiangsu. The land was fertile and products were plentiful. As the waves lashed the shore, the land turned saline and alkaline. The local people became destitute and homeless. When he served as the magistrate of Xinghua, Fan Zhongyan encouraged the local people to build a breakwater dozens of kilometres long. The people returned to their homeland and called the breakwater "Lord Fan Embankment". ~

“At the beginning of the 11th century, troops of Yuanhao, King of the Western Xia regime, incessantly harassed the northwest border of the Northern Song Dynasty, causing serious losses of the people's lives and property. The troops of the Song Dynasty suffered one defeat after another. Fan Zhongyan was appointed the deputy military commissioner of Shaanxi. He displayed outstanding military talent and followed a policy of national concord. A peace treaty was signed between the Western Xia regime and the Northern Song Dynasty. ~

“After the war, Fan Zhongyan was transferred to the capital and appointed a participant in determining governmental matters. In 1043, the third year of the reign of Qingli, Emperor Renzong granted an audience to his ministers, seeking their opinions on major policies. Fan Zhongyan proposed a reform in the administration of local officials and nine other reforms. Historically they were known as "Qingli New Policies". The New Policies failed in about a year because of opposition from conservative officials. Fan Zhongyan was forced to leave the imperial court, but he was still concerned about his country and people.” ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021