FORMS AND MATERIALS IN CHINESE PAINTING

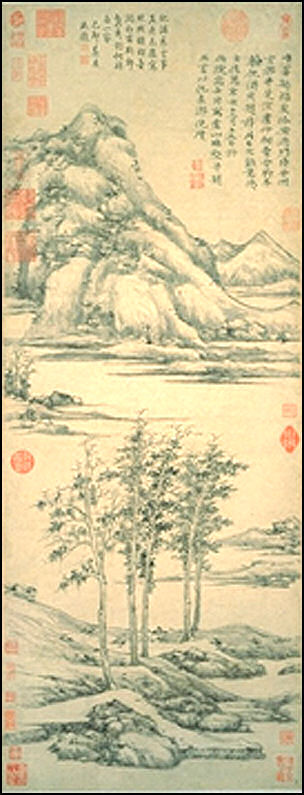

Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu by Ni Zan

Chinese paintings and works of calligraphy were generally not painted on canvas like Western painting. They appear as murals, wall paintings, album leaf paintings, hanging scrolls and handscrolls. Hanging scrolls are hung on walls as interior adornments; handscrolls are unrolled on table tops; and album leaf paintings are small paintings of various shapes collected in book-like albums with "butterfly mounting," "thatched window mounting" and “accordion mounting."

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: "“In Chinese painting and calligraphy, the purpose of mounting works of art is for the ease and convenience of appreciation and storage. Mountings can be divided into three general categories: hanging scrolls, handscrolls, and album leaves. Hanging scrolls are usually suspended on walls, often as a form of decoration in residences. Handscrolls are for works of painting and calligraphy that are horizontally oriented. When taken out for appreciation on a tabletop, handscrolls are often unrolled one section at a time from right to left. The album leaf, as the name suggests, involves mounting an individual work of art into a single page. When combined with others, they form an album, much like a book. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: ““Chinese painting uses water-based inks and pigments on either paper or silk grounds. Black ink comes from lampblack, a substance made by burning pine resins or tung oil; colored pigments are derived from vegetable and mineral materials. Both are manufactured by mixing the pigment source with a glue base, which is then pressed into cake or stick form; using a special stone, the artist must grind the ink back into a watery solution immediately before painting. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“The brush used for painting is very similar to the one used for calligraphy, but there is greater variety in the shapes and resilience of brushes used in painting. The two different types of painting surfaces, silk and paper, both require sizing, or treatment with a glue-like substance on their uppermost surface, to prevent ink and pigment from soaking into and being completely absorbed by the ground. Silk remains less porous than paper, and is somewhat water-resistant, especially after sizing. As a result, applying paint to a silk surface requires more painstaking techniques, building up ink and colors carefully and gradually in layers. Paper, in contrast, is more absorbent and is favored for spontaneous effects.

Unlike artists in the West who were either skilled craftsmen paid by the hour or professional artists who were commissioned to produce unique works of art, Chinese artists were mostly amateur scholar gentlemen "following revered ancients in harmony with forces of nature." Calligraphy and painting were seen as scholarly pursuits of the educated classes, and in most cases the great masters of Chinese art distinguished themselves first as government officials, scholars and poets and were usually skilled calligraphers. Sculpture, which involved physical labor and was not a task performed by gentlemen, never was considered a fine art in China. See Separate Article CHINESE PAINTERS factsanddetails.com

See Separate Articles: CHINESE PAINTING: THEMES, STYLES, AIMS AND IDEAS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; ART FROM CHINA'S GREAT DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; GREAT AND FAMOUS CHINESE PAINTINGS factsanddetails.com ; SUBJECTS OF CHINESE PAINTING: INSECTS, FISH, MOUNTAINS AND WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTINGS OF GHOSTS AND GODS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TAOIST ART: PAINTINGS OF GODS, IMMORTALS AND IMMORTALITY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTERS factsanddetails.com ; PAINTING FROM THE TANG, SONG, YUAN, MING AND QING DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; TANG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ANIMAL, RELIGIOUS AND FIGURE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; YUAN ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; MING DYNASTY PAINTING AND ITS FOUR GREAT MASTERS factsanddetails.com ; QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Painting” by James Cahill (Rizzoli 1985) Amazon.com; “Chinese Painting Style: Media, Methods, and Principles of Form” by Jerome Silbergeld Amazon.com; “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” by Richard M. Barnhart, et al. (Yale University Press, 1997); Amazon.com; “How to Read Chinese Paintings” by Maxwell K. Hearn (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008) Amazon.com; “Brushstrokes: Styles and Techniques of Chinese Painting” by So Kam Ng Lee and So Kam Ng Amazon.com ; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Displaying and Viewing Chinese Painting

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Chinese tradition of displaying a painting is quite distinct from that of Europe. Hanging scrolls might be brought out for special occasions; they might reflect the marking of a season or a special event. After the passing of such an event, however, the scroll would be put away. Because works on silk and paper are light sensitive, they cannot be kept out for long periods of time. As a result, the viewing of paintings was always a special occasion. This is also true for handscrolls. One would bring the scroll out either to regard and enjoy by oneself, or perhaps with one or two others at most. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant, learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu]

Dawn Delbanco of Columbia University wrote: “ A significant difference between Eastern and Western painting lies in the format. Unlike Western paintings, which are hung on walls and continuously visible to the eye, most Chinese paintings are not meant to be on constant view but are brought out to be seen only from time to time. This occasional viewing has everything to do with format. [Source: Dawn Delbanco Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University, Metropolitan Museum of Art \^/]

“A predominant format of Chinese painting is the handscroll, a continuous roll of paper or silk of varying length on which an image has been painted, and which, when not being viewed, remains rolled up. Ceremony and anticipation underlie the experience of looking at a handscroll. When in storage, the painting itself is several layers removed from immediate view, and the value of a scroll is reflected in part by its packaging. Scrolls are generally kept in individual wooden boxes that bear an identifying label. Removing the lid, the viewer may find the scroll wrapped in a piece of silk, and, unwrapping the silk, encounters the handscroll bound with a silken cord that is held in place with a jade or ivory toggle. After undoing the cord, one begins the careful process of unrolling the scroll from right to left, pausing to admire and study it, shoulder-width section by section, rerolling a section before proceeding to the next one.\^/

“Reading” Chinese Painting

Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The Chinese way of appreciating a painting is often expressed by the words du hua, "to read a painting." How does one do that? Consider Night-Shining White by Han Gan, an image of a horse. Originally little more than a foot square, it is now mounted as a handscroll that is twenty feet long as a result of the myriad inscriptions and seals (marks of ownership) that have been added. Miraculously, the animal's energy shines through. It does so because the artist has managed to distill his observations of both living horses and earlier depictions to create an image that embodies the vitality and form of an iconic "dragon steed." He has achieved this with the most economical of means: brush and ink on paper. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, \^/]

“This is the aim of the traditional Chinese painter: to capture not only the outer appearance of a subject but its inner essence as well—its energy, life force, spirit. To accomplish his goal, the Chinese painter more often than not rejected the use of color. Like the photographer who prefers to work in black and white, the Chinese artist regarded color as distraction. He also rejected the changeable qualities of light and shadow as a means of modeling, along with opaque pigments to conceal mistakes. Instead, he relied on line—the indelible mark of the inked brush.\^/

“Amateur and professional alike shared a reverence for the past. Artists would manipulate antique styles and reinterpret ancient subjects to lend historical resonance to their work. But the weight of past precedents was also a heavy burden that could make painters acutely self-conscious. Sometimes their solutions were eccentric and challenged the viewer's ability to judge them by what had preceded them. At other times, a knowledge of past models made them keenly aware of the illusionistic power of art, the capacity to mimic reality as well as to distort it.\^/

“To "read" a Chinese painting is to enter into a dialogue with the past; the act of unrolling a scroll or leafing through an album provides a further, physical connection to the work. An intimate experience, it is one that has been shared and repeated over the centuries. And it is through such readings, enjoyed alone or in the company of friends, that meaning is gradually revealed.” \^/

Calligraphy and Painting Tools

The tools and brush techniques for painting and calligraphy are virtually the same and calligraphy and painting are often considered sister arts. The traditional tools of the calligrapher and the painter are a brush, ink and an inkstone (used to mix the ink). Chinese calligraphers and painters both used brushes whose unique versatility was the result of a tapered tip, composed of careful groupings of animal hairs. Chinese calligraphers prized bamboo brushes tipped with hair from the thick autumn coats of martens.

Many brushstrokes depict things found in nature such as a "rolling wave," "leaping dragon," "playful butterfly," "dewdrop about to fall," or "startled snake slithering through the grass." Natural terms such as "flesh," "muscle" and "blood" are used to describe the art of calligraphy itself. Blood, for example, is a term used to describe the quality of the ink. Calligrapher’s paper is still made by hand in some places by smoothing oatmeal-like pulp made of inner tree bark and rice and pressing and drying it.

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”, published in in 1894: “The Chinese pride themselves upon being a literary nation, in fact the literary nation of the world. Pens, paper, ink, and ink-slabs are called the"four precious things," and their presence constitutes a “literary apartment." It is remarkable that not one of these four indispensable articles is carried about the person. They are by no means sure to be at hand when wanted, and all four of them are utterly useless without a fifth substance, to wit, water, which is required for rubbing up the ink. The pen cannot be used without considerable previous manipulation to soften its delicate hairs, it is very liable to be injured by inexpert "handling, and lasts but a Comparatively short time. The Chinese have no substitute for the pen, such as lead pencils, nor if they had them, would they be able to keep them in repair, since they have no pen-knives, and no pockets in which to carry them. We have previously endeavoured, in speaking of the economy of the Chinese, to do justice to their great skill in accomplishing excellent results with very inadequate means, but it is not the less true that such labour saving devices as are so constantly met in Western lands, are unknown in China. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

Inscriptions and Seals on Chinese Paintings

Many Chinese paintings and works of calligraphy are covered with inscriptions and seals, often so much so they seem to dominate of the painting. Dawn Delbanco of Columbia University wrote: “Many handscrolls contain inscriptions preceding or following the image: poems composed by the painter or others that enhance the meaning of the image, or a few written lines that convey the circumstances of its creation. Many handscrolls also contain colophons, or commentary written onto additional sheets of paper or silk that follows the image itself. These may be comments written by friends of the artist or the collector; they may have been written by viewers from later generations. The colophons may comment on the quality of the painting, express the rhapsody (rarely the disenchantment) of the viewer, give a biographical sketch of the artist, place the painting within an art-historical context, or engage with the texts of earlier colophons. And as a final way of making their presence known, the painter, the collectors, the one-time viewers often "sign" the image or colophons with personal seals bearing their names, these red marks of varying size conveying pride of authorship or ownership.\^/ [Source: Dawn Delbanco Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University, Metropolitan Museum of Art \^/]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ “Most Chinese paintings have small red impressions in a stylized script, placed either inconspicuously at the painting's outer boundaries, or scattered liberally through the image area itself. These seals (or "chops") can indicate either who executed the painting or who owned it. Carved in a soft stone and impressed with a waxy, oil-based ink paste in vermilion red, the seals use an ancient script type that was in use mainly during the Zhou and Qin dynasties; this gives the characters an archaic quality that is often highly abstract. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Most seals are square; some are round or gourd shaped. The names inscribed on the seal stone are typically the literary or personal name of the owner. Historians use seals to trace the later history of a painting, to see who owned and viewed the painting and which later artists may have been influenced by it. The seal is one tool art historians and connoisseurs have used to authenticate paintings, but like signatures and the paintings themselves, these seals can be copied or forged and therefore may prove to be less than reliable evidence.

“The design or layout of words by the seal carver evolved into an art form in itself, the challenge being fitting the relatively predictable forms of characters into an interesting composition where there was very little leeway for bold experimentation. The characters can be carved in relief (resulting in red figures on a white ground as you see here at left) or engraved (with characters appearing in white on a solid red background). The characters in the seal at left belong to a publisher, the Renmin meishu chubanshe of Beijing. The simplest character, ren, is in the upper right hand corner.

Evolution of Inscriptions on Chinese Painting

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Colophons, or inscriptions, are one of the more striking features of Chinese paintings that are unfamiliar to western audiences. In the west, not until the twentieth century do we see text and art image interact to the same degree on the surface of the art work. Early narrative paintings in the Chinese tradition often displayed text in banners next to the figures depicted; portions of the associated narrative text were also frequently found interspersed with sections of the painting. Beginning around the 11th century, however, poems and painted images were designed to share the same image space. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“Although this practice was common at court, it was with the scholar painters that the practice of writing on the painting surface became firmly established. Literati painters also appended notes concerning the circumstances of creation of particular paintings. These writings, added after the painting was completed, could be mounted together with the painting but on another piece of paper or silk (as was the case with handscrolls) or even invaded the picture surface itself (as in the case of the album leaf or the hanging scroll). The content of these inscriptions typically included the appreciative comments of later viewers and collectors and constituted a major source of enjoyment for connoisseurs, who felt a connection to art aficionados and scholars of the past through their writings.

Zhang Zhen, an expert in ancient Chinese painting and calligraphy with the Palace Museum in Beijing told the China Daily: "The practice of inscribing a painting — writing down the painter's thoughts, often in the form of poetry, on a finished work's empty space — started during the Song Dynasty," says Zhang. "The fad quickly became standard practice. During the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912), there was almost no piece of literati painting that wasn't inscribed." [Source: Zhao Xu And Su Qiang, China Daily, December 19, 2015]

“Mindful of the inscriptions that would later appear, in composing their works painters took full account of the calligraphy that would appear with the painting, an aesthetic consideration far broader than the question of where the calligraphy would be placed. One example is an ink painting of fish by the Qing Dynasty painter Li Fangying (1695-1756). The calligraphy on the right side of the painting effectively evokes the riverbank and indicates the water that was never painted.

“Maxwell Hearn, chairman of the Department of Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, says: "What is striking to me is that the educated elite of China has, since Song times, practiced painting and calligraphy as related forms of self-expression. Certainly this was only possible because of the universal competency in calligraphy, which was one of the distinguishing factors in what it meant to be an educated individual in China. In the West, good handwriting did not necessarily lead to a competency in drawing. ... Consequently, the practice of penmanship among literate individuals did not lead to a class of literati artists in the West. "Instead, the creation of wall paintings or paintings in oil on canvas required the mastery of an entirely different set of skills and media. Furthermore, paintings were usually time-consuming undertakings that involved specialized materials. Consequently, painting became the purview of specialists - professionals - who worked on commission. Only in the last century has painting in the West been regarded as the pure expression of individual painters."

40-Centimeter Chinese Painting With Six Meters of Inscriptions and Seals

Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Consider Night-Shining White by Han Gan, an image of a horse. Originally little more than a foot square, it is now mounted as a handscroll that is twenty feet long as a result of the myriad inscriptions and seals (marks of ownership) that have been added over the centuries, some directly on the painted surface, so that the horse is all but overwhelmed by this enthusiastic display of appreciation.” [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art]

“Chinese scholar-officials “covered Night-Shining White with inscriptions and seals. Their knowledge of art enabled them to determine that the image was a portrait of an imperial stallion by a master of the eighth century. They recognized that the horse was meant as an emblem of China's military strength and, by extension, as a symbol of China itself. And they understood the poignancy of the image. Night-Shining White was the favorite steed of an emperor who led his dynasty to the height of its glory but who, tethered by his infatuation with a concubine, neglected his charge and eventually lost his throne. \^/

“The emperor's failure to put his stallion to good use may be understood as a metaphor for a ruler's failure to properly value his officials. This is undoubtedly how the retired scholar-official Zhao Mengfu intended his image of a stallion, painted 600 years later, to be interpreted. Expertise in judging fine horses had long been a metaphor for the ability to recognize men of talent. Zhao's portrait of the horse and groom may be read as an admonition to those in power to heed the abilities of those in their command and to conscientiously employ their talents in the governance of their people.\^/

“Once poetic inscriptions had become an integral part of a composition, the recipient of the painting or a later appreciator would often add an inscription as his own "response." Thus, a painting was not finalized when an artist set down his brush, but it would continue to evolve as later owners and admirers appended their own inscriptions or seals. Most such inscriptions take the form of colophons placed on the borders of a painting or on the endpapers of a handscroll or album; others might be added directly on to the painting. In this way, Night-Shining White was embellished with a record of its transmission that spans more than a thousand years.” \^/

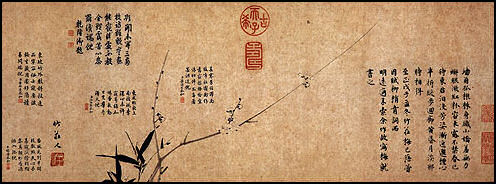

Plum and Bamboo by Wu Zhen

Scrolls and Ways to Display Chinese Painting

There are the five main formats for Chinese paintings: 1) hanging scrolls; 2) hand scrolls; 3) album leaves; 4) fans; and 5) standing screens. Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ The hanging scroll displays an entire painting at one viewing and typically ranges in height from two to six feet. It can be thought of as a lightweight, changeable wall painting. The earliest hanging scrolls may be related developmentally to tomb banners, which are known from the early Han dynasty. Hanging scrolls came to be used with greater regularity from the tenth century onward. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

“Handscrolls are typically between nine and fourteen inches in height but may vary greatly in length; one of the longer paintings discussed in this unit is almost 29 feet long. Like the hanging scroll, the handscroll is lightweight and portable. However, only one portion (usually a shoulders' width) is viewed at a time. Thus, the experience of looking at this type of painting is very different from that of the hanging scroll or wall painting. Because of this feature, the artist can take advantage of the visual pacing of the painted elements to encourage the viewer to look more quickly in some some sections or to linger over details in others.

“Album leaves were first used for painting during the Song; their use likely stems from printing and book binding practice. Albums were quite small and intimate in scale, and often juxtaposed poetry and painting on facing pages.

“Flat oval fans are known from Tang times or earlier. The period dating from the late Northern Song through the Southern Song saw the production of many paintings in this format, which was well suited to the abbreviated, lyrical images prevalent at the time.

“One other format, the standing screen painting, because it was used as a functional home furnishing element, deteriorated rapidly through frequent movement and exposure. Paintings produced for screens were often salvaged and remounted as hanging scrolls. Many of the paintings that we know today in one format may well have originated in another and could have been used in another context entirely.

Chinese Handscrolls

Many Chinese art masterpieces are painted on scrolls, which are not intended to be hung or mounted on walls, but rather are meant to be stored in boxes and periodically taken out to be looked at. This helps preserve the frail paint which breaks down when exposed to humidity and air. Collectors have traditionally unrolled their scrolls after the rainy season in the summer, savored them with some tea and returned them their boxes. Handscroll paintings were generally much longer than they were wide. Compositions were focused from left to right and most scrolls contained one painting although some had several short paintings mounted together. One 85-foot-long silk handscroll from 1550 contained 1,000 figures and 785 horses.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: If one considers the act of unrolling a handscroll, one can see that it can only be unrolled at a certain distance — the distance with which it can be held open with two hands. Thus, the act of handling and viewing a handscroll makes for a very intimate encounter with the work of art, and perhaps this is why the Chinese, in addition to preferring the handscroll format, have always valued the mark of the artist — the "heart print" of the artist communicated through his brush work — as being the most important aspect of a work of art, rather than a visually faithful representation of the external world. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant ]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““When works of painting or calligraphy are mounted in the horizontal handscroll format, they are glued to a wooden roller (mu-kun) at the left end to form an axis around which to roll the scroll. At the beginning of the mounting (i.e., the right end), a wooden stave (t'ien-kan) serves as the outer end support. On this is attached a silk cord (tai-tzu) and a fastener (pieh-tzu), which are used to secure the scroll after it is rolled up. At the back of the scroll attached to the stave is a protective flap of heavy silk (pao-shou) that also serves as decoration. On top of this flap is a title label (t'I-ch'ien) that allows identification of the work without unrolling it. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The height of a handscroll is generally about thirty centimeters but can reach fifty or sixty, which is known as a large-mounting handscroll (kao-t'ou ta-chuan). Because the width of handscroll paintings is greater than the height, compositions usually unfold gradually from right to left. Now, for the sake of convenience during display, a large section or the entire scroll is unrolled at once. In the past, however, the proper way to view a handscroll was to unroll with the left hand and roll with the right at the same time, thereby examining one section at a time. The part on view was always that which could be comfortably opened. This intimate and consecutive method of appreciating works differs from the "all-at-once" one of viewing hanging scrolls or album leaves. Artists have taken advantage of this unique feature of the horizontal scroll by adapting subject matter, such as by encompassing events from different times in the same composition for a dramatic effect. With the handscroll format, a world of Chinese painting literally unfolds before the eyes of the viewer.

History of Chinese Handscrolls

The first handscrolls, dating back to the Spring and Autumn period (770-481 B.C.), appeared in ancient books and documents and were made mostly from bamboo or wood strips bound together with chord. Beginning in the Eastern Han Period (25-220 A.D.) silk and paper were commonly used. Until the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 690-906), most books and documents were kept as handscrolls that were around a foot and half wide and varied in length from a few inches to several hundred feet. The proper way to look at a book-style handscroll is to hold it vertically, unroll it from the left and roll it from the right, examining a section at a time.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “One might wonder why the Chinese came to use the handscroll as a format for painting. Consider that almost all early writing systems began with scrolls, such as the papyrus rolls of Egypt, which continued to be used during Roman times. The Torah, the Hebrew Bible, was also written on a scroll, for early materials used for writing, such as papyrus, could not be folded into book form, but had to be rolled. The same was true in China: In earlier periods the Chinese used woven silk or strips of bamboo tied together as a writing surface, and the most efficient way to mount these surfaces was as long rolls. So the scroll format long preceded the use of the codex, or book. And in China the scroll persisted as the format of choice for artists who wanted to create long, narrative pieces, and in particular long, landscape scenes. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant ]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The origins of the handscroll format lie in the ancient texts and documents of China. From the Spring and Autumn period (770-481 B.C.) through the Han Dynasty (206B.C.-AD 220), texts were chiefly written down on slips of bamboo or wood. These narrow strips were then bound together side-by-side with cords to form a series that could be rolled up. From the Eastern Han period (25-220), the use of paper and silk became more common, and these materials were mounted to form handscrolls following in this traditional format. Up until the Tang dynasty (618-907), the handscroll was the principal format for texts. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Originally, the labels on ancient scrolls were mostly inside, and the frontal section of silk or paper, known as the "heaven (t'ien-t'ou)," was very short. However, from the Yuan (1279-1368) and Ming (1368-1644) dynasties, the label gradually came to be placed outside, and the "heaven" became longer, from which developed a space for writing the frontispiece (yin-shou) and thus making for a complete format. The title of the work or an inscription is often found here in seal or clerical script, and to the left of the title would be the painting itself (hua-hsin). Handscrolls can be as short as ten centimeters or as long as several hundred, or even thousand. Furthermore, most handscrolls contain only one painting, but several short ones can be mounted together one after another. To the left of the painting, sections of colophon paper (pa-chih) provide space for connoisseurs and collectors to express their admiration or record other information. Vertical strips (ko-shui) often serve as boundaries to separate the sections of the scroll (such as the painting, preface inscription, and colophons). Since the Six Dynasties period (A.D. 222-589), the handscroll format has developed into a standard form of mounting, but with much room for variation as each generation seeks new twists on tradition (see the accompanying diagrams for the most common types).

Scrolls unfortunately are one of the world's most fragile art forms. Careless handling, exposure to bright light and humidity, inept restoration, insects, temperature changes all contribute to the deterioration of paint. Plus, silk is a protein-based animal fiber that breaks down over time and has damaging chemical reactions with pigments and glues. Western oil paintings, by contrast, lasts longer because the pigments are preserved in oil and protected from the elements by varnish.

Viewing Chinese Handscrolls

Dawn Delbanco of Columbia University wrote: “The experience of seeing a scroll for the first time is like a revelation. As one unrolls the scroll, one has no idea what is coming next: each section presents a new surprise. Looking at a handscroll that one has seen before is like visiting an old friend whom one has not seen for a while. One remembers the general appearance, the general outlines, of the image, but not the details. In unrolling the scroll, one greets a remembered image with pleasure, but it is a pleasure that is enhanced at each viewing by the discovery of details that one has either forgotten or never noticed before.\^/ [Source: Dawn Delbanco Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University, Metropolitan Museum of Art \^/]

“Looking at a handscroll is an intimate experience. Its size and format preclude a large audience; viewers are usually limited to one or two. Unlike the viewer of Western painting, who maintains a certain distance from the image, the viewer of a handscroll has direct physical contact with the object, rolling and unrolling the scroll at his or her own desired pace, lingering over some passages, moving quickly through others.\^/

“The format of a handscroll allows for the depiction of a continuous narrative or journey: the viewing of a handscroll is a progression through time and space—both the narrative time and space of the image, but also the literal time and distance it takes to experience the entire painting. As the scroll unfurls, so the narrative or journey progresses. In this way, looking at a handscroll is like reading a book: just as one turns from page to page, not knowing what to expect, one proceeds from section to section; in both painting and book, there is a beginning and an end.\^/

“Indeed, this resemblance is not incidental. The handscroll format—as well as other Chinese painting formats—reveals an intimacy between word and image.” A “handscroll is both painted image and documentary history; past and present are in continuous dialogue. Looking at a scroll with colophons and inscriptions, a viewer sees not only a pictorial representation but witnesses the history of the painting as it is passed down from generation to generation.\^/

Making Chinese Handscrolls

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: To produce large scrolls, a master artist would first create a series of draft scrolls — full-size renditions on paper — wherein he would sketch out the content of each scroll. He would do this in ink and light color on paper, with only suggestions of where figures might be placed. These draft scrolls would then be submitted to the emperor for his approval. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant ]

“After the official approval of the drafts, the silk and lavish mineral colors to be used in the final version would be issued to the artist. The draft scrolls would then become the reference for a team of artists who would set to work on the final paintings, each following his specific area of specialization. Some artists on the team were specialists in architectural rendering, others in the painting of human figures, and still others in landscape detail.

“It is unlikely that the master artist, Wang Hui in the case of the inspection tour scrolls of the Kangxi Emperor, painted much of the final scrolls himself. His team of subordinates were experienced artists whom he had recruited and brought to the capital specifically to complete this project. All of these artists had been trained to paint in a style that was consistent with his own. Though Wang Hui probably closely monitored their work and the overall production process, the enormous task of actually painting these twelve monumental scrolls mostly fell to this team of subordinate specialists.”

Album Leaves

Pages from the the Mustard Seed Manual Using album leaves likely stems from printing and book binding practice.s Albums were quite small and intimate in scale, and often featured poetry and painting on facing pages. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The album leaf format was already found in the Tang dynasty (618-907) and its use for mounting works of painting and calligraphy perhaps derived from Buddhist sutras. Handscroll sutras from the Six Dynasties period (222-589) were mounted into albums during the early Tang in order to facilitate research and reading. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The album leaf format can be divided into three basic mounting types; the "butterfly, " "accordion, " and "thatched-window" mountings. The "butterfly" mounting refers to albums that open into double leaves divided into right and left sides. The height of the painting is usually less than the width, which accounts for the fold down the middle like a pair of wings. The second album leaf format is the "accordion" mounting, which is especially used for albums with many leaves. The height is often greater the width, and both round fans and squarish leaves are suitable for this type. With the leaves connected, the album opens like an accordion, hence the name. The third is the "thatched-window" mounting, which refers to albums that open into double leaves, one atop the other. The name derives from the thatched windows on river boats that were opened from below in a similar manner. This format is suitable for mounting folding fans or paintings that are wider than they are high.

“For both the "butterfly" and "thatched window" mountings, the simplest arrangement is that of a painting coupled with a blank leaf. Occasionally, a poem is mounted on the matching leaf (to the left in the "butterfly" and above in the "thatched window" mountings). An album is usually comprised of an even number of leaves, such as eight, twelve, sixteen, or more, and divided into sets of albums. Blank leaves are usually placed at the front and end of the album, and pieces of stiff paper or wood act as the front and back covers, similar to a book.

Album Leaf Paintings and Mountings

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Album leaf paintings are almost always small in scale, though they can be tall like hanging scrolls or long like handscrolls and of many different shapes; rectangular, square, round, oval, gourd-shaped…. Because of their scale, compositions often differ from those in hanging scrolls or handscrolls. Landscapes, for example, frequently focus on the most beautiful and concise scenes. The artist's challenge is to bring out beauty and variety in such small views. Flowers, birds, and other animals even more so follow the adage that " a single flower or leaf is a whole. A skillful artist thus can take the viewer into an intimate and enchanting realm using only a few centimeters of space.

The basic form of the album leaf can be divided into three general types: 1) "Butterfly" (Horizontal) Mounting: Opened left or right, as in a book, another piece opposite the work is often found. Appearing like the wings of a butterfly when opened, it is also known as a "fold mounting". 2) "Push-awning" (Vertical) Mounting: Opening the top for viewing, the work is placed in the lower section, in a format similar to a traditional window shutter pushed open vertically. This is suitable for mounting works that are wider than they are tall and also known as a "folding fan covering". 3) "Sutra Fold" (Accordion) Mounting: This format is so named because it was originally used for the copying and reciting of Buddhist scriptures (known as sutras). Several works of painting or calligraphy are connected together so that, after the mounting is complete, they can be laid flat and unfolded one at a time. It can then be folded back, like an accordion, to form an album.

“A typical album usually consists of an even number of leaves — often in multiples of two, such as 8, 12, 16, or even more — that form a set. In general, the work of art found in an album leaf is rather small, with taller ones sometimes being mounted as a small hanging scroll and longer ones as a small handscroll. There are album leaves that are square, round, oval, and gourd-shaped, with all sorts of fan shapes also remounted as album leaves. Due to its small size, the entire scenery in a leaf can be seen at a single glance, making it easier to understand the main idea and appreciate its most beautiful parts. Though perfectly displaying the work of art in such a small space, plenty of room for the imagination still remains in this intimate format, making the album leaf an ideal microcosm to bring the viewer into the world of the artist's mind.

Fans

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Fans were a common means of cooling off in the past, and their surfaces were often decorated with painting and/or calligraphy, becoming one of the unique art formats for painting in ancient China. As part of the social interaction among Chinese scholars was the reciprocal giving of fans as well as cooperative production of painting and calligraphy on their surfaces, fans became an intricate part of the elegant pastimes in scholarly life. In earlier periods, painters and calligraphers mainly used the silk surface of round fans, but by the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), after the folding fan became popular, the paper surface of this format became an alternative for painting and calligraphy. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Round fans (known in Chinese as “wan-shan” or “t’uan-shan”) are not usually circular in form, but actually more squarish with rounded corners. With short handles, they were often used in the palaces of ancient times and hence known as “palace fans”. Round fans also have a uniquely decorative function, in which various grades of silk textile were specifically chosen and then adorned with calligraphed poetry or a small painting to enhance their aesthetic quality.

“Hibiscus Blossoms” is Song Dynasty (960-1279) is a round fan at the National Palace Museum, Taipei mounted as an album leaf made of ink and color on silk and measuring 25-x -26.2 centimeters. Depicting a branch of hibiscus, this work was done in the method of outlining the forms and filling them with color. The brushwork here is natural yet forceful. The outlining of the petals and the saw-tooth edges and veins of the leaves also reveal brushwork that is quite skillful. The stems, pistils, and backs of the leaves are all washed with shades of blue-green for a realistic effect. Though this work bears no signature or seal of the artist, the style includes features quite similar to those found in renderings of flowers in the Song Dynasty imperial Painting Academy.

“The folding fan, when extended, forms an arched shape. As the name suggests, it can be folded into a compact form. Said to have originally derived from tribute gifts sent from Korea and Japan, it became popular in China at least by the Northern Sung period (960-1126). Even then, one can find precedents of fan surfaces decorated with painting and calligraphy. Becoming a favorite medium for scholar painters and calligraphers wielding the brush, this art form flourished approximately in the period of the Four Great Masters of the Ming dynasty — Shen Chou, Wen Cheng-ming, Tang Yin, and Ch’iu Ying, who helped foster the trend of painting and calligraphy on folding fans. In the Ming dynasty, there were even shops that produced folding fans and specially made fan paper for sale. Without the slats inserted between the front and back pieces of paper, it made them convenient for writing and mounting, hence the name “surfaces of convenience”. Mounting into the album leaf format allows them also to be conveniently collected and appreciated as well.

“Peach Blossoms” by Ch'en Hung-shou (1599-1652), Ming Dynasty is a folding fan mounted as an album leaf, made of ink and color on paper, and measuring 18 x 53.5 centimeters. Ch'en Hung-shou was a native of Chu-chi, Zhejiang. He was a professional painter who retained his scholarly manner. He often used exaggereated forms to create a sense of archaism, and his compositions exhibit a high degree of originality. In this work, a new twig springs from the old trunk of a peach tree, its strong and hoary quality forming a perfect contrast with the small and subtle blossoms, which are linked together with a ribbon. Done in 1622, this is the earliest painting by Ch’en in the Museum collection and still reveals the influence of his teacher, Lan Ying.

Mounting Chinese Painting and Calligraphy

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The mounting of painting or calligraphy is a unique Chinese craft that has a long history of over a thousand years. Known by a variety of terms in Chinese, the mounting includes the backing of the artwork itself and often incorporates silk borders and various other portions and accessories. A work of painting and calligraphy not properly mounted is much more difficult to appreciate and preserve for posterity. Works must not only be suitably mounted but also done so in an aesthetically pleasing manner to complement the contents. In fact, back in the Ming dynasty, Chou Chia-chou (1582-ca. 1661) in The Book of Mounting wrote, "a mounter is in charge of a painting or calligraphy's fate" and "one cannot overlook paying attention to the mountings of treasured painting and calligraphy." In other words, the art of mounting is a vital part of traditional painting and calligraphy. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“If an ancient work shows serious sign of damage, its mounting inevitably must be removed for repairs and the work remounted. The restored backing and remounting of an ancient artwork can bring it back to life and to its former brilliance, making this craft even more important. The collection of painting and calligraphy in the National Palace Museum includes more than 10,000 works and sets. Among the most valuable ones are masterpieces dating from the Tang and Song Dynasties or earlier. If mounters over the ages had not fastidiously cared for these works from more than a thousand years ago, how could they have been preserved in their present state for all to appreciate now?

“The formats of Chinese painting and calligraphy can be divided into the four general categories — hanging scrolls, handscrolls, album leaves, and fans, with considerable variety in each group. Hanging scrolls, for example, include large hall, narrow side, paired couplet, and continuous scenery types. Handscrolls may feature thin, covered, or wrapping borders. Album leaves come in a wide range of folding (page), butterfly (horizontal) folded, push-awning (top-bottom page), and sutra-fold (accordion) mountings, while fans appear in parasol, circular or rounded, and folding varieties.”

Image Sources: Wikipedia; University of Washington; Nolls China website; Palace Museum, Taipei, Shanghai Museum

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021