TANG DYNASTY ART

Beauty playing go

Ideas and art flowed into China on the Silk Road along with commercial goods during the Tang period (A.D. 607-960). Art produced in China at this time reveals influences from Persia, India, Mongolia, Europe, Central Asia and the Middle East. Tang sculptures combined the sensuality of Indian and Persian art and the strength of the Tang empire itself. Art critic Julie Salamon wrote in the New York Times, that artists in the Tang dynasty “absorbed influences from all over the world, synthesized them and a created a new multiethnic Chinese culture."

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In plastic art there are fine sculptures in stone and bronze, and we have also technically excellent fabrics, the finest of lacquer, and remains of artistic buildings; but the principal achievement of the Tang period lies undoubtedly in the field of painting. As in poetry, in painting there are strong traces of alien influences; even before the Tang period, the painter Hsieh Ho laid down the six fundamental laws of painting, in all probability drawn from Indian practice. Foreigners were continually brought into China as decorators of Buddhist temples, since the Chinese could not know at first how the new gods had to be presented. The Chinese regarded these painters as craftsmen, but admired their skill and their technique and learned from them. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Proto-porcelain evolved during the Tang dynasty. It was made by mixing clay with quartz and the mineral feldspar to make a hard, smooth-surfaced vessel. Feldspar was mixed with small amounts of iron to produce an olive-green glaze. Tang funerary vessels often contained figures of merchants. warriors, grooms, musicians and dancers. There are some works that have Hellenistic influences that came via Bactria in Afghanistan and Central Asia. Some Buddhas of immense size were produced. None of the tombs of the Tang emperors have been opened but some tombs of the royal family members have excavated, Most of them were thoroughly looted. The most important finds have been murals and paintings in lacquer. They contain delightful images of court life.

Tang- and Five Dynasties-era paintings in collection at National Palace Museum, Taipei include: 1) "Emperor Ming-huang's Flight to Sichuan", Anonymous; 2) "Mansions in the Mountains of Paradise" by Tung Yuan (Five Dynasties); and 3) "Herd of Deer in an Autumnal Grove", Anonymous. Works of calligraphy from the same period in the museum include: 1) "Clearing After Snowfall" (Wang Hsi-chih, Chin Dynasty); and 2) "Autobiography" by Huai-su, (T'ang Dynasty).

Good Websites and Sources on the Tang Dynasty: Wikipedia ; Google Book: China’s Golden Age: Everday Life in the Tang Dynasty by Charles Benn books.google.com/books; Empress Wu womeninworldhistory.com ; Good Websites and Sources on Tang Culture: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Tang Poems etext.lib.virginia.edu enter Tang Poems in the search; Chinese History: Chinese Text Project ctext.org ; 3) Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu ; Chaos Group of University of Maryland chaos.umd.edu/history/toc ; 2) WWW VL: History China vlib.iue.it/history/asia ; 3) Wikipedia article on the History of China Wikipedia Books: “Daily Life in Traditional China: The Tang Dynasty”by Charles Benn, Greenwood Press, 2002; "Cambridge History of China" Vol. 3 (Cambridge University Press); "The Culture and Civilization of China", a massive, multi-volume series, (Yale University Press); "Chronicle of the Chinese Emperor" by Ann Paludan. Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TANG, SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; SUI DYNASTY (A.D. 581-618) AND FIVE DYNASTIES (907–960): PERIODS BEFORE AND AFTER THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; CHINESE PAINTING: THEMES, STYLES, AIMS AND IDEAS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTING FORMATS AND MATERIALS: INK, SEALS, HANDSCROLLS, ALBUM LEAVES AND FANS factsanddetails.com ; SUBJECTS OF CHINESE PAINTING: INSECTS, FISH, MOUNTAINS AND WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; TANG DYNASTY (A.D. 690-907) factsanddetails.com; TANG EMPERORS, EMPRESSES AND ONE OF THE FOUR BEAUTIES OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; TANG DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; TANG SOCIETY, FAMILY LIFE AND WOMEN factsanddetails.com; TANG DYNASTY GOVERNMENT, TAXES, LEGAL CODE AND MILITARY factsanddetails.com; CHINESE FOREIGN RELATIONS IN THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; TANG DYNASTY (A.D. 690-907) CULTURE, MUSIC, LITERATURE AND THEATER factsanddetails.com; TANG DYNASTY POETRY factsanddetails.com; LI PO AND DU FU: THE GREAT POETS OF THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; TANG HORSES AND TANG ERA SCULPTURE AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD DURING THE TANG DYNASTY (A.D. 618 - 907) factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Amazon.com; “China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty” by Charles Benn Amazon.com; “China’s Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty” by Mark Edward Lewis, Timothy Brook, Amazon.com “Chinese Landscape Painting: In the Sui and Tang Dynasties” by Michael Sullivan Amazon.com; “Han and T'Ang Murals” by Jan Fontein Wu Tung Amazon.com; “Tang and Liao ceramics” by Wiliam Watson Amazon.com; Painting: “Chinese Painting” by James Cahill (Rizzoli 1985) Amazon.com; “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” by Richard M. Barnhart, et al. (Yale University Press, 1997); Amazon.com; “Masterpieces of Chinese Painting 700-1900" by Hongxing Zhang Amazon.com; “How to Read Chinese Paintings” by Maxwell K. Hearn (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008) Amazon.com; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Tang Dynasty Painting

Zhang Xuan, Palace Ladies Pounding Silk

During the Tang Dynasty both figure painting and landscape painting reached great heights of maturity and beauty. Forms were carefully drawn and rich colors applied in painting that were later called "gold and blue-green landscapes." This style was supplanted by the technique of applying washes of monochrome ink that captured images in abbreviated, suggestive forms. During the late Tang dynasty bird, flower and animal painting were especially valued. There were two major schools of this style of painting: 1) rich and opulent and 2) "untrammeled mode of natural wilderness." Unfortunately, few works from the Tang period remain.

Famous Tang dynasty paintings include Zhou Fang's “Palace Ladies Wearing Flowered Headdresses,” a study of several beautiful, plump women having their hair done; Wei Xian's The Harmonious Family Life of an Eminent Recluse, a Five Dynasties portrait of a father teaching his son in a pavilion surrounded by jagged mountains; and Han Huang's Five Oxen, an amusing depiction of a five fat oxen. Lovely murals were discovered in the tomb of Princess Yongtain, the granddaughter of Empress Wu Zetian (624?-705) on the outskirts of Xian. One shows a lady-in-waiting holding a nyoi stick while another lady holds glassware. It is similar to tomb art found in Japan. A painting on silk cloth dated to the A.D. mid-8th century found in the tomb of a rich family in the Astana tombs near Urumqi in western China depicts a noblewoman with rouge cheeks deep in concentration as she plays go.

According to the Shanghai Museum:“During the Tang and Song periods, Chinese painting matured and entered a stage of full development. Figure painters advocated "appearance as a vehicle conveying the spirit", emphasizing the internal spiritual quality of paintings. Landscape painting was divided into two major schools: the blue-and-green and the ink-and-wash styles. Various skills of expression were created for flower-and-bird paintings such as realistic meticulous painting with color,ink-and-wash painting with light color and boneless ink-wash painting. The Imperial Art Academy flourished during the northern and southern Song dynasties.The southern Song witnessed a trend of simple and bold strokes in landscape paintings. Literati ink-and-wash painting became a unique style developing outside the Academy, which stressed free expression of artists' personality. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

Tang Dynasty Painters

Celebrated Tang-era painters included Han Gan (706-783), Zhang Xuan (713-755), and Zhou Fang (730-800). The court painter Wu Daozi (active ca. 710–60) was famous for his naturalist style and vigorous brushwork. Wang Wei (701–759) was admired as a poet, painter and calligrapher. who said "there are paintings in his poems and poems in his paintings."

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The most famous Chinese painter of the Tang period is Wu Daozi, who was also the painter most strongly influenced by Central Asian works. As a pious Buddhist he painted pictures for temples among others. Among the landscape painters, Wang Wei (721-759) ranks first; he was also a famous poet and aimed at uniting poem and painting into an integral whole. With him begins the great tradition of Chinese landscape painting, which attained its zenith later, in the Song epoch. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: "It was from the Six Dynasties (222-589) to the Tang dynasty (618-907) that the foundations of figure painting were gradually established by such major artists as Gu Kaizhi (A.D. 345-406) and Wu Daozi (680-740). Modes of landscape painting then took shape in the Five Dynasties period (907-960) with variations based on geographic distinctions. For example Jing Hao (c. 855-915) and Guan Tong (c. 906-960) depicted the drier and monumental peaks to the north while Dong Yuan (?–962) and Juran (10th century) represented the lush and rolling hills to the south in Jiangnan. In bird-and-flower painting, the noble Tang court manner was passed down in Sichuan through the style of Huang Quan (903–965), which contrasts with that of Xu Xi (886-975) in the Jiangnan area. The rich and refined style of Huang Quan and the casual rusticity of Xu Xi's manner also set respective standards in the circles of bird-and-flower painting. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Ladies with Flowered Headresses by Zhou Fang

Tang Dynasty Paintings

“Ode on Pied Wagtails” by Tang Emperor Xuanzong (685-762) is a handscroll, ink on paper (24.5 x 184.9 centimeters): According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In the autumn of 721, about a thousand pied wagtails perched at the palace. Emperor Xuanzong (Minghuang) noticed pied wagtails give out a short and shrill cry when in flight and often wag their tails in a rhythmic manner when walking about. Calling and waving to each other, they seemed to be especially close, which is why he likened them to a group of brothers demonstrating fraternal affection. The emperor ordered an official to compose a record, which he personally wrote to form this handscroll. It is the only surviving example of Xuanzong's calligraphy. The brushwork in this handscroll is steady and the use of ink rich, having a force of vigor and magnanimity in every stroke. The brushwork also clearly reveals pauses and transitions in the strokes. The character forms are similar to those of Wang Xizhi's (303-361) characters assembled into "Preface to the Sacred Teaching" composed in the Tang dynasty, but the strokes are even more robust. It demonstrates the influence of Xuanzong’s promotion of Wang Xizhi's calligraphy at that time and reflects the trend towards plump aesthetics in the High Tang under his reign.” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“A Palace Concert” by an anonymous Tang dynasty artist is hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk (48.7 x 69.5 centimeters). According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “This painting depicts ten ladies of the women's quarters from the inner palace. They are seated around the sides of a large rectangular table served with tea as someone is also drinking wine. The four figures at the top are playing a Tartar double-reed pipe, pipa, guqin zither, and reed pipe, bringing festivity to the figures enjoying their banquet. To the left is a female attendant holding a clapper that she uses to keep rhythm. Although the painting has no signature of the artist, the plump features of the figures along with the painting method for the hair and clothing all accord with the aesthetic of Tang dynasty ladies. Considering the short height of the painting, it is surmised to have originally once been part of a decorative screen at the court during the middle to late Tang dynasty, later being remounted into the hanging scroll seen here.” \=/

Emperor Minghuang Playing Go by Zhou Wenju (ca. 907-975) is a Five Dynasties period (Southern Tang), Handscroll, ink and colors on silk (32.8 x 134.5 centimeters): According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ The subject here is attributed to the Tang emperor Minghuang’s (Xuanzong, 685-762) fondness of playing "weiqi" (go). He sits on a dragon chair by a go board. A man in red goes to discuss a matter, his back adorned with a jester, suggesting that he is a court actor. The coloring here is elegant, the drapery lines delicate, and the figures’ expressions all fine. The Qing emperor Qianlong's (1711-1799) poetic inscription criticizes Minghuang for his infatuation with the concubine Yang Guifei, attributing his eventual neglect of state affairs for the calamities that befell the Tang dynasty. Scholarly research also suggests this handscroll may depict Minghuang playing go with a Japanese monk. The old attribution is to the Five Dynasties figure painter Zhou Wenju, but the style is closer to that of the Yuan dynasty artist Ren Renfa (1254-1327).

“Gibbons and Horses”, attributed to Han Kan (fl. 742-755), Tang dynasty, is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 136.8 x 48.4 centimeters. In this work of bamboo, rocks, and trees are three gibbons among branches and on a rock. Below are a black and a white steed leisurely trotting. The inscription and yu-shu ("imperial work") seal of the Northern Song emperor Hui-tsung and "Treasure of the Ch'i-hsi Hall" seal of the Southern Song emperor Li-tsung are spurious and later additions. All the motifs are finely rendered, though, suggesting a Southern Song (1127-1279) date. With no seal or signature of the artist, this work was attributed in the past to Han Kan. A native of Ta-liang (modern K'ai-feng, Henan), he is also said to be from Ch'ang-an or Lan-t'ien. Called to court in the T'ien-pao era (742-755), he studied under Ts'ao Pa and was famous for painting horses, being admired by the Tang critic Chang Yen-Yuan.

Taizong gives audience to the envoy of Tibet

“Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy” by Yan Liben

"Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy" by painter Yan Liben (600-673) is treasured both as a masterpiece of Chinese painting and a historical document. Yan Liben was one of the most revered Chinese figure painters of the Tang dynasty. Housed at the Palace Museum in Beijing and rendering on relatively course silk, the painting is 129.6 centimeters long and 38.5 centimeters wide. It depicts the friendly encounter between the Tang dynasty Emperor and an envoy from Tubo (Tibet) in 641. [Source: Xu Lin, China.org.cn, November 8, 2011]

In 641, the Tibetan envoy — the the Prime Minister of Tibet came to Chang’an (Xian), the Tang capital, to accompany Tang Princess Wencheng— who would marry the Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo (569 -649) — back to Tibet. The marriage was an important event in both Chinese and Tibetan history, establishing a strong bon between the two states and peoples. In the painting, the emperor sits on a sedan surrounded by maids holding fans and canopy. He looks composed and peaceful. On the left, one person in red is the official in the royal court. The envoy stands aside formally and holds the emperor in awe. The last person is an interpreter.

Marina Kochetkova wrote in DailyArt Magazine: “In 634, on an official state visit to China, Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo fell in love with and pursued Princess Wencheng’s hand. He sent envoys and tributes to China but was refused. Consequently, Gampo’s army marched into China, burning cities until they reached Luoyang, where the Tang Army defeated the Tibetans. Nevertheless, Emperor Taizong (598–649) finally gave Gampo Princess Wencheng in marriage. [Source: Marina Kochetkova, DailyArt Magazine, June 18, 2021]

“As with other early Chinese paintings, this scroll is probably a Song dynasty (960–1279) copy from the original. We can see the emperor in his casual attire sitting on his sedan. On the left, one person in red is the official in the royal court. The fearful Tibetan envoy stands in the middle and holds the emperor in awe. The person farthest to the left is an interpreter. Emperor Taizong and the Tibetan minister represent two sides. Therefore, their different manners and physical appearances reinforce the dualism of the compo-sition. These differences emphasize Taizong’s political superiority.

Yan Liben uses vivid colors to portray the scene. Moreover, he skillfully outlines the characters, making their expression lifelike. He also depicts the emperor and the Chinese official larger than the others to emphasize the status of these characters. Therefore, not only does this famous handscroll have historical significance but it also shows artistic achievement.

Painting of Beautiful Tang Dynasty Noble Ladies

"Noble Ladies in Tang Dynasty" are a series of paintings drawn by Zhang Xuan (713–755) and Zhou Fang (730-800), two of the most influential figure painters during the Tang dynasty, when . noble ladies were popular painting subjects. The paintings depict the leisurely, peaceful life of the ladies at court, who are rendered as dignified, beautiful and graceful. Xu Lin wrote in China.org: Zhang Xuan was famous for integrating lifelikeness and casting a mood when painting life scenes of noble families. Zhou Fang was known for drawing the full-figure court ladies with soft and bright colors. [Source: Xu Lin, China.org.cn, November 8, 2011]

Tang Court Ladies

Marina Kochetkova wrote in DailyArt Magazine: “During the Tang dynasty, the genre of “beautiful women painting” enjoyed popularity. Coming from a noble background, Zhou Fang created artworks in this genre. His painting Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers illustrate the ideals of feminine beauty and the customs of the time. In the Tang dynasty, a voluptuous body symbolized the ideal of feminine beauty. Therefore, Zhou Fang depicted the Chinese court ladies with round faces and plump figures. The ladies are dressed in long, loose-fitting gowns covered by transparent gauzes. Their dresses are decorated with floral or geometric motifs. The ladies stand as though they are fashion models, but one of them is entertaining herself by teasing a cute dog. [Source: Marina Kochetkova, DailyArt Magazine, June 18, 2021]

“Their eyebrows look like butterfly wings. They have slender eyes, full noses, and small mouths. Their hairstyle is done up in a high bun adorned with blossoms, such as peonies or lotuses. The ladies also have a fair complexion as a result of the application of white pigment to their skin. Although Zhou Fang portrays the ladies as works of art, this artificiality only enhances the ladies’ sensuality.

“By placing human figures and non-human images, the artist makes analogies be-tween them. Non-human images enhance the delicacy of the ladies who are also fixtures of the imperial garden. They and the ladies keep each other company and share each others’ loneliness. Zhou Fang not only exceled in portraying the fashion of the time. He also revealed the court ladies’ inner emotions through the subtle depiction of their facial expressions.

Five Oxen by Han Huang

"Five Oxen" was painted by Han Huang (723–787), a prime minister in the Tang Dynasty. The painting was lost during the occupation of Beijing after the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 and later recovered from a collector in Hong Kong during the early 1950s. The 139.8-centimeter-long, 20.8-centimeter- wide painting now resides in the Palace Museum in Beijing. [Source: Xu Lin, China.org.cn, November 8, 2011]

Xu Lin wrote in China.org.cn: “The five oxen in varied postures and colors in the painting are drawn with thick, heavy and earthy brushstrokes. They are endowed with subtle human characteristics, delivering the spirit of the willingness to bear the burden of hard labor without complaints. Most of the paintings recovered from ancient China are of flowers, birds and human figures. This painting is the only one with oxen as its subject that are represented so vividly, making the painting one of the best animal paintings in China's art history.

Marina Kochetkova wrote in DailyArt Magazine: “Han Huang painted his Five Oxen in different shapes from right to left. They stand in line, appear happy or depressed. We can treat each image as an independent painting. However, the oxen form a unified whole. Han Huang carefully observed the details. For example, horns, eyes, and expressions show different features of the oxen. As for Han Huang, we do not know which ox he would choose and why he painted Five Oxen. In the Tang dynasty, horse painting was in vogue and enjoyed imperial patronage. By contrast, ox painting was traditionally considered an unsuitable theme for a gentleman’s study. [Source: Marina Kochetkova, DailyArt Magazine, June 18, 2021]

Three of the Five Oxen by Han Huang

Night Revels of Han Xizai

“The Night Revels of Han Xizai”, by Gu Hongzhong (937-975) is an ink and color on silk handscroll measuring 28.7 centimeters by 335.5 centimeters that survived as a copy made during the Song dynasty. Regarded as one of the masterpieces of Chinese art, it depicts Han Xizai, a minister of the Southern Tang emperor Li Yu, partying with more than forty realistic-looking people. persons. [Source: Wikipedia]

The main character in the painting is Han Xizai, a high official who, according to to some accounts, attracted suspicion the Emperor Li Yu and pretended to withdraw from politics and become addicted to a life of revelry, to protect himself. Li sent Gu from the Imperial Academy to record Han's private life and famous artwork was the result. Gu Hongzhong was reportedly sent to spy on Han Xizai. According to one version of the story, Han Xizai repeatedly missed morning audiences with Li Yu due to his excessive revelry and needed to be shamed into behaving properly. In another version of the story, Han Xizai refused Li Yu's offer to become prime minister. To check Han's suitability and find out what he was doing at home, Li Yu sent Gu Hongzhong alongside another court painter, Zhou Wenju, to one of Han's night parties and depict what they saw. Unfortunately, the painting made by Zhou was been lost.

The painting is divided into five distinct parts showing Han’s banquet and contains a seal of Shi Miyuan, a Song dynasty official. Viewed from right to left, the painting shows 1) Han listening to a pipa (a Chinese instrument) with his guests; 2) Han beating a drum for some dancers; 3) Han taking a rest during the break; 4) Han listening to wind instrument music; and 5) the guests socializing with the singers. All of the more than 40 people in the painting look lifelike and have different expressions and postures. [Source: Xu Lin, China.org.cn, November 8, 2011]

Female musicians played flutes. While in the early Tang period shows musicians played sitting on floor mats, the painting shows them sitting on chairs. Despite the popular title of the work, Gu depicts a somber rather than with atmosphere. None of the people are smiling. The painting is believed to have helped Li Yu downplay some of his distrust in Han, but did little to prevent the decline of Li's dynasty.

Tang-Era Landscapes

Jing Hao, Mount Kuanglu

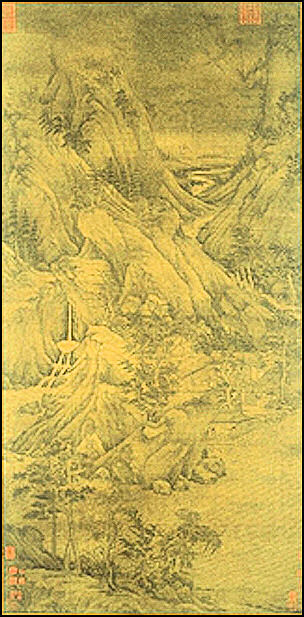

“Traveling Through Mountains in Spring” by Li Zhaodao (fl. ca. 713-741) is a hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk ( 95.5 x 55.3 centimeters): According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Using fine yet strong lines, this archaic work is actually a later "blue-and-green" landscape painting in the manner of Li Zhaodao. Furthermore, despite the title, this work actually portrays the escape of the Tang emperor Xuanzong (685-762), also known as Minghuang, to Sichuan during the An Lushan Rebellion. To the right figures and horses descend from the peaks to the valley, while the man before a small bridge is probably the emperor. Clouds coil, peaks rise, and mountain paths wind, emphasizing precarious plank paths using the composition of "Emperor Minghuang’s Flight to Sichuan” as a model.” The landscape paintings of Li Zhaodao, the son of the painter and general Li Sixun, followed in the family tradition and equaled those of his father, earning him the nickname "Little General Li." The compositions of his paintings are tight-knit and skillful. When painting rocks, he first drew outlines with fine brushwork and then added umber, malachite green, and azurite blue. Sometimes he would even add highlights in gold to give his works a bright, luminous feeling. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Early Snow on the River” by Chao K'an (fl. 10th century) of the Five Dynasties Period (Southern Tang) period is an ink and colors on silk handscroll, measuring 25.9 x 376.5 centimeters. Because the painting is very rare and fragile it almost never displayed. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Chao K'an sprayed dots of white color for a realistic effect to suggest wind-driven flakes of snow. Chao K'an's centered brushwork outlining the bare trees is also powerful, and the tree trunks were textured with dry strokes to suggest light and dark. Chao also creatively depicted the reeds using single flicks of the brush, and he modeled the land forms without using formulaic strokes. The history of the seal impressions indicates that this masterpiece was treasured in both private and imperial collections starting from the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

“This authentic early landscape painting on silk also includes vivid descriptions of figures. The Southern Tang ruler Li Yu (r. 961-975) at the beginning of the scroll to the right wrote, Early Snow on the River by Student Chao K'an of the Southern Tang," providing contemporary proof of both the title and artist. Chao K'an was a native of Jiangsu province who spent his life in the lush Jiangnan area. Not surprisingly, his landscape painting here shows the water-filled scenery typical of the area. Unrolling this scroll from right to left shows the activities of fishermen zigzagging among isolated expanses of water. Despite the falling snow, fishermen continue to toil away to make a living. Travelers on the bank also make their way in the snow, the artist showing the bitter cold through the expressions on their faces. The bare trees and dry reeds only add to the desolation of the scene.

“Dwellings in Autumnal Mountains”, attributed to Chu-jan (fl. late 10th century) of the Five Dynasties period is an ink on silk hanging scroll, measuring 150.9x103.8 centimeters. “In the middleground of this work rises a massive mountain as an encircling river flows diagonally across the composition. “Hemp-fiber” strokes model the mountains and rocks while layers of washes imbue them with a sense of dampness. This unsigned painting bears an inscription by the famous Ming connoisseur Tung Ch'i-ch'ang, who considered it a Chu-jan original. Unmistakable similarities with Spring Dawn over the River by Wu Chen (1280-1354) in terms of composition as well as brush and ink, however, suggest that these two works came from the same hand. “Chu-jan, a native of Nanking, was a monk at the K'ai-Yuan Temple. He excelled at painting landscapes and followed the style of Tung Yuan.

Dong Yuan's "Riverbank" and "Xiao and Xiang Rivers"

Don Yuan's Riverbank

Dong Yuan is a legendary 10th-century Chinese painter and a scholar in the court of the Southern Tang Dynasty. He created one of the "foundational styles of Chinese landscape painting." “Along he Riverbank”, a 10th-century silk scroll he painted, is perhaps the rarest and most important early Chinese landscape painting. Over seven feet long, “The Riverbank” is an arrangement of soft contoured mountains, and water rendered in light colors with ink and brushrstokes resembling rope fibers. In addition to establishing a major form of landscape painting, the work also influenced calligraphy in the 13th and 14th century.

Maxwell Heran, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art told the New York Times: "Art-historically, Dong Yuang is like Giotto or Leonardo: there at the start of painting, except the equivalent moment in China was 300 years before.” In 1997, “The Riverbank” and 11 other major Chinese painting were given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York by C.C. Wang, a 90-year-old painter who escaped from Communist China in the 1950s with painting which he hoped he could trade for his son.

Dong Yuan (c. 934 – c. 964) was born in Zhongling (present-day Jinxian County, Jiangxi Province). He was a master of both figure and landscape painting in the Southern Tang Kingdom of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period (907-979). He and his pupil Juran founded the Southern style of landscape painting. So strong was Dong Yuan’s influence that his elegant style and brushwork was still the standard by which Chinese brush painting was judged almost a thousand years after his death. His most famous masterpiece ‘Xiao and Xiang Rivers’ showcases his exquisite techniques and his sense of composition. Many art historians consider “Xiao and Xiang Rivers” to be Dong Yuan’s masterpiece: Other famous works are “Dongtian Mountain Hall” and “Wintry Groves and Layered Banks.” "Riverbank" is ranked so highly by U.S. critic perhaps is because — as it is owned by Metropolitan Museum of Art — it is one of the few Chinese masterpieces in the U.S.

“Xiao and Xiang Rivers” (also known as “Scenes along the Xiao and Xiang Rivers”) is an ink on silk hanging scroll, measuring 49.8 x 141.3 centimeters. It is regarded as masterpieces based on its exquisite techniques and his sense of composition. The softened mountain line makes the immobile effect more pronounced while clouds break the background mountains into a central pyramid composition and a secondary pyramid. The inlet breaks the landscape into groups makes the serenity of the foreground more pronounced. Instead of simply being a border to the composition, it is a space of its own, into which the boat on the far right intrudes, even though it is tiny compared to the mountains. Left of center, Dong Yuan uses his unusual brush stroke techniques, later copied in countless paintings, to give a strong sense of foliage to the trees, which contrasts with the rounded waves of stone that make up the mountains themselves. This gives the painting a more distinct middle ground, and makes the mountains have an aura and distance which gives them greater grandeur and personality. He also used "face like" patterns in the mountain on the right. [Source: Wikipedia]

Song Era Paintings on Tang Themes

“Leaving Behind the Helmet: by Li Gonglin (1049-1106) from the Song dynasty is handscroll, ink on paper (32.3 x 223.8 centimeters). According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ In 765, the Tang dynasty was invaded by a large army headed by the Uighurs. Guo Ziyi (697-781) was ordered by the Tang court to defend Jingyang but was hopelessly outnumbered. When the advancing army of Uighurs heard of Guo's renown, their chieftain requested a meeting with him. Guo thereupon took off his helmet and armor to lead a few dozen cavalry and meet the chieftain. The Uighur chieftain was so impressed by Guo's loyalty to the Tang and his bravery that he also discarded his weapons, dismounted, and bowed in respect. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“This story is illustrated using the "baimiao" (ink outline) method of painting. In it, Guo Ziyi is shown leaning over and holding out his hand as a mutual sign of respect at the meeting, reflecting the composure and magnanimity of this famous general at the time. The lines in the drapery patterns here flow with ease, having much of the pure and untrammeled quality of literati painting. Although this work bears a signature of Li Gonglin, judging from the style, it appears to be a later addition.”\=/

“Beauties on an Outing” by Li Gonglin (1049-1106) is handscroll, ink and colors on silk (33.4 x 112.6 centimeters): According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ This work is based on the poem "Beauties on an Outing” by the famous Tang poet Du Fu (712-770), who described therein the opulent beauty of noble ladies from the states of Qin, Han, and Guo. The figures of the ladies here are plump and their faces done with white makeup. The horses are muscular as the ladies proceed on horseback in a leisurely and carefree manner. In fact, all the figures and horses, as well as the clothing, hairstyles, and coloring method, are in the Tang dynasty style. \=/

A late Northern Song copy of a Tang rendition on this subject by the Painting Academy ("Copy of Zhang Xuan's 'Spring Outing of Lady Guo'") is very similar in composition to this painting. Though this work bears no seal or signature of the artist, later connoisseurs attributed it to the hand of Li Gonglin (perhaps because he specialized in figures and horses). However, judging from the style here, it was completed probably sometime after the Southern Song period (1127-1279). “ \=/

A Palace Concert

“My Friend” by Mi Fu (151-1108) is an album leaf rubbing, ink on paper (29.7x35.4 centimeters): According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Mi Fu (style name Yuanzhang), a native of Xiangfan in Hubei, once served as an official in various localities when younger, and the court of Emperor Huizong employed him as an Erudite of Painting and Calligraphy. He was also gifted at poetry, painting, and calligraphy. With a keen eye, Mi Fu amassed a large art collection and became known along with Cai Xiang, Su Shi, and Huang Tingjian as one of the Four Masters of Northern Song Calligraphy. \=/

“This work comes from the fourteenth album of Modelbooks in the Three Rarities Hall. The original work was done between 1097 and 1098, when Mi Fu was serving in Lianshui Prefecture, representing the peak of his career. In this letter, Mi Fu gives a recommendation for cursive script to a friend, saying that he should select from the virtues of Wei and Jin calligraphers and pursue an archaic manner. The brushwork throughout this work is sharp and fluent. Though unbridled, it is not unregulated. Marvelous brushwork emerges from the dots and strokes as the characters appear upright and leaning in an agreeable composition of line spacing. Creating a maximum effect of change, it overflows with the vigor of straightforward freedom. The “tang” character chosen for the Tang Prize comes from Mi Fu’s calligraphy.” \=/

Mogao Caves

Mogao Grottoes (17 miles south of Dunhuang) — also known as Thousand Buddha Caves — is a massive group of caves filled with Buddhist statues and imagery that were first used in the A.D. 4th century. Carved into a cliff on the eastern side of Singing Sand Mountain and stretching for more than a mile, the grottoes are one of the largest treasure house of grotto art in China and the world.

Outside Mogao Caves

All together there are 750 caves (492 with art work) on five levels, 45,000 square meters of murals, more than 2000 painted clay figures and five wooden structures. The grottoes contain Buddha statues and lovely paintings of paradise, asparas (angels) and the patrons who commissioned the paintings. The oldest cave dates back to the 4th century. The largest cave is 130 feet high. It houses a 100-foot-tall Buddha statue installed during the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618-906). Many caves are so small they can only can accommodate a few people at a time. The smallest cave is only a foot high.

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “Within the caves, the monochrome lifelessness of the desert gave way to an exuberance of color and movement. Thousands of Buddhas in every hue radiated across the grotto walls, their robes glinting with imported gold. Apsaras (heavenly nymphs) and celestial musicians floated across the ceilings in gauzy blue gowns of lapis lazuli, almost too delicate to have been painted by human hands. Alongside the airy depictions of nirvana were earthier details familiar to any Silk Road traveler: Central Asian merchants with long noses and floppy hats, wizened Indian monks in white robes, Chinese peasants working the land. In the oldest dated cave, from A.D. 538, are depictions of bandits bandits that had been captured, blinded, and ultimately converted to Buddhism."Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

“Carved out between the fourth and 14th centuries, the grottoes, with their paper-thin skin of painted brilliance, have survived the ravages of war and pillage, nature and neglect. Half buried in sand for centuries, this isolated sliver of conglomerate rock is now recognized as one of the greatest repositories of Buddhist art in the world. The caves, however, are more than a monument to faith. Their murals, sculptures, and scrolls also offer an unparalleled glimpse into the multicultural society that thrived for a thousand years along the once mighty corridor between East and West.

A total of 243 caves have been excavated by archaeologists, who have unearthed monk's living quarters, meditation cells, burial chambers, silver coins, wooden printing blocker written in the Uighar and copies Psalms of written in the Syriac language, herbal pharmacopoeias, calendars, medical treatises, folk songs, real estate deals, Taoist tracts, Buddhist sutras, historical records and documents written in dead languages such as Tangut, Tokharian, Runic and Turkic.

See Separate Article MOGAO CAVES: ITS HISTORY AND CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

Mogao Cave 148 (Tang, A.D. 705-781)

Mogao Cave 249

According to the Dunhuang Research Academy: “This cave has a transverse rectangular layout (17x7.9m) and a vaulted roof. The interior looks like a big coffin because its main theme is the Buddha’s nirvana (his demise; the liberation from existence). Because of the special shape of this cave, it has no trapezoidal top. The Thousand-Buddha motif is painted on the flat and rectangular ceiling. This motif is original, yet the colours are still as bright as new. On the long altar in front of the west wall is a giant reclining Buddha made of stucco on a sandstone frame. It is 14.4m long, signifying the Mahaparinirvana (the great completed nirvana). More than 72 stucco statues of his followers, restored in the Qing, surround him in mourning. [Source: Dunhuang Research Academy, March 6, 2014 public.dha.ac.cn ^*^]

Mogao Cave contains “the largest and best painting about Nirvana in Dunhuang....The Buddha is lying on his right, which is one of the standard sleeping poses of a monk or nun. His right arm is under his head and above the pillow (his folded robe). This statue was later repaired, but the ridged folds of his robe still retain the traits of High Tang art. There is a niche in each of the north and south walls, although the original statues inside were lost. The present ones were moved from somewhere else. ^*^

“On the west wall, behind the altar, is the beautifully untouched jingbian, illustrations of narratives from the Nirvana Sutra. The scenes are painted from south to north, and occupy the south, west and north walls with a total area of 2.5x23m. The complete painting consists of ten sections and 66 scenes with inscriptions in each; it includes more than 500 images of humans and animals. The inscriptions explaining the scenes are still legible. The writings in ink read from top to bottom and from left to right, which is unconventional. However, the inscription written in the Qing dynasty on the city wall in one of the scenes is written from top to bottom and from right to left, the same as conventional Chinese writing. Both of these writing styles are popular in Dunhuang. ^*^

“In the seventh section, the funeral procession is leaving town on the way to Buddha’s cremation. The casket in the hearse, the stupa and other offerings, which are carried by several dharma protectors in front, are elaborately decorated. The procession, including Bodhisattvas, priests and kings carrying banners and offerings, is solemn and grand. ^*^

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons: Mogao caves: Dunhuang Research Academy, public.dha.ac.cn ; Digital Dunhuang e-dunhuang.com

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021