TANG DYNASTY CULTURE

Dance figurines

The Tang Dynasty was a golden age for the Chinese arts. Landscape painting and ceramic and bronze sculpture, including Tang horses, were perfected. Chinese acrobatics and dance also took off. The Tang is considered the greatest age for Chinese poetry. Two of China's most famous poets, Li Bai and Du Fu, were active as were the celebrated painters Han Gan, Zhang Xuan, and Zhou Fang. There was a rich variety of historical literature compiled by scholars, as well as encyclopedias and geographical works. Influential innovations included the development of woodblock printing and advanced water clocks. Buddhism was a major influence in Chinese culture as were native Chinese sects. Even when dynasty and central government were in decline by the 9th century, art and culture continued to flourish.

John D. Szostak of the University of Washington wrote: “Tang aristocratic and affluent society was strongly influenced by foreign music and arts. Central Asian musicians and dancers were highly appreciated both in the Tang court as well as on the popular level. Aromatic dishes made from expensive imported ingredients and spices were served to the wealthy, accompanied by wine made from grapes. Chinese women set their hair in the Uighur manner, while fashionable men adopted Turkic leggings, tight-fitted bodices and headgear. [Source: John D. Szostak, University of Washington washington.edu ]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The eighth century heralded the second important epoch in Tang history, achieved largely during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–56), called minghuang—the Brilliant Monarch. It is rightfully ranked as the classical period of Chinese art and literature, as it set the high standard to which later poets, painters, and sculptors aspired. The expressions and images contained in the poems of Li Bo (ca. 700–762) and Du Fu (722–770) reflect the flamboyant lives of the court and the conflicting sentiments generated by military campaigns. The vigorous brushwork of the court painter Wu Daozi (active ca. 710–60) and the naturalist idiom of the poet and painter Wang Wei (701–759) became artistic paradigms for later generations. [Source: Department of Asian Art, "Tang Dynasty (618–906)", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org October 2001 \^/]

See Separate Articles on TANG POETRY and TANG ART

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TANG, SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; SUI DYNASTY (A.D. 581-618) AND FIVE DYNASTIES (907–960): PERIODS BEFORE AND AFTER THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; TANG DYNASTY (A.D. 690-907) factsanddetails.com; TANG EMPERORS, EMPRESSES AND ONE OF THE FOUR BEAUTIES OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; TANG DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; TANG SOCIETY, FAMILY LIFE AND WOMEN factsanddetails.com; TANG DYNASTY GOVERNMENT, TAXES, LEGAL CODE AND MILITARY factsanddetails.com; CHINESE FOREIGN RELATIONS IN THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; TANG DYNASTY POETRY factsanddetails.com; LI PO AND DU FU: THE GREAT POETS OF THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; TANG DYNASTY ART: PAINTING, CALLIGRAPHY AND BUDDHIST CAVE ART factsanddetails.com; TANG HORSES AND TANG ERA SCULPTURE AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD DURING THE TANG DYNASTY (A.D. 618 - 907) factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Tang Dynasty Tales: A Guided Reader Paperback” by William H Nienhauser Jr Amazon.com; “Tales from Tang Dynasty China: Selections from the Taiping Guangji” by Alexei Ditter, Jessey Choo, Sarah Allen Amazon.com; “China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty” by Charles Benn Amazon.com; “Three Hundred Tang Poems” by Peter Harris Amazon.com; “Five T'ang Poets Paperback” by Wang Wei, Li Po, Tu Fu, Li Ho, Li Shang-yin Amazon.com “Du Fu: A Life in Poetry” by Du Fu Amazon.com; “Li Po and Tu Fu: Poems” Amazon.com; “The Banished Immortal: A Life of Li Bai (Li Po) by Ha Jin, David Shih, Amazon.com; “The Selected Poems of Li Po” by Li Po, Amazon.com; “China’s Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty” by Mark Edward Lewis, Timothy Brook, Amazon.com

Metropolitan Culture of Tang Era China

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: “Literature, the visual arts, and music flourished and the theatrical arts were evolving towards their present forms. The most influential capital of the dynasty was Changan (C’hang-an) (currently Xi’an, Hsi-an) in Central China. During the Tang dynasty it was the world's biggest metropolis. A vast network of caravan routes, generally known as the Silk Road, connected Changan with Central Asia, India, Persia and finally with the Mediterranean world. The influence of Tang culture spread to Korea as well as to Japan, where two of its capitals, Nara and Kyoto, were built according to the city plan of Changan." [Source:Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki]

According to Silk Road Foundation: Peace and prosperity prevailed during Tang. Population tripled from the 630s to 755, the year when nearly 9 million families and 53 million people were recorded. It was a century of low prices and of economic stabilization and an age of movement, when settlers migrated in great number. Around the 8th century, the capital of the Tang dynasty was the biggest, wealthiest, and most advanced city the world. It is called Ch'ang-an, meaning "long-lasting peace" and was the center of the largest empire on earth. While London was just a market town of a few thousand people, Ch'ang-an and its suburbs lived around two million people. [Source: “Exoticism in Tang (618-907), Silkroad Foundation”, Silk Road Foundation silk-road.com ]

“Tang welcomed other cultures and other people. Chinese life and Chinese art had been touched by strong foreign influences during the Tang dynasty. One would pass people from almost everywhere in the streets. Merchants from Central Asia, with thick beards, sold wine from goatskin bags. Blond women shopped in the market. Religious pilgrims from Central Asia or India wandered the streets in sandals. Settling into the life of Ch'ang-an, the visitor would discover a culture as sophisticated as that in a modern global center like New York or Paris.”

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The crowding of people into the capital and the accumulation of resources there promoted a rich cultural life. We know of many poets of that period whose poems were real masterpieces; and artists whose works were admired centuries later. These poets and artists were the pioneers of the flourishing culture of the later Tang period. Hand in hand with this went luxury and refinement of manners. For those who retired from the bustle of the capital to work on their estates and to enjoy the society of their friends, there was time to occupy themselves with Taoism and Buddhism, especially meditative Buddhism. Everyone, of course, was Confucian, as was fitting for a member of the gentry, but Confucianism was so taken for granted that it was not discussed. It was the basis of morality for the gentry, but held no problems. It no longer contained anything of interest.

“Conditions had been much the same once before, at the court of the Han emperors, but with one great difference: at that time everything of importance took place in the capital; now, in addition to the actual capital, Ch'ang-an, there was the second capital, Loyang, in no way inferior to the other in importance; and the great towns in the south also played their part as commercial and cultural centres that had developed in the 360 years of division between north and south. There the local gentry gathered to lead a cultivated life, though not quite in the grand style of the capital. If an official was transferred to the Yangtze, it no longer amounted to a punishment as in the past; he would not meet only uneducated people, but a society resembling that of the capital. The institution of governors-general further promoted this decentralization: the governor-general surrounded himself with a little court of his own, drawn from the local gentry and the local intelligentsia. This placed the whole edifice of the empire on a much broader foundation, with lasting results.

Influence of Central Asia Culture on the Tang Dynasty

Sogdian Central Asian Buddhist monks

Ping-Ti Ho wrote: “There was also another kind of “barbarization” that may be more correctly described as “Central-Asianization” or “Western-Asianization.” Throughout the period 600-900 there was the continual introduction of Central and Western Asian music; dance; magic; acrobatics; polo; Turkish and other ethnic costumes; various exotic foods including grape wines, refined granular cane sugar, many types of pancakes and pastry; and certain nomad ways of cooking meats. In early T’ang it was fashionable to learn to speak and to act Turkish. The best-known case was the illstarred first heir apparent of T’ai-tsung, prince Ch’eng-ch’ien. In the realm of interracial, interethnic, and interfaith dealings, the openmindedness and large-heartedness of the early T’ang Chinese are nowhere better shown than in the words of T’ang T’ai-tsung, who, after receiving the Nestorian monk 0 Lo Pen in 635, expressed his opinion on religions in general, including Nestorian Christianity: The Way has more than one name. There is more than one Sage. Doctrines vary in different lands, their benefits reach all mankind. 0 Lo Pen, a man of great virtue from Ta Ts’in (the Roman Empire) has brought his images and books from afar to present them in our capital. After examining his doctrines we find them profound and pacific. After studying his principles we find that they stress what is good and important. His teaching is not diffuse and his reasoning is sound. This religion does good to all men. Let it be preached freely in Our Empire. (Fitzgerald 1935, 336) [Source: Excerpted from Ping-Ti Ho, “In Defense of Sinicization: A Rebuttal of Evelyn Rawski’s “Reenvisioning the Qing,” ” The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 57, No. 1 (Feb., 1998), pp. 123-155 ]

“Although the specific circumstances of their introduction were not clearly recorded, Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism were equally welcomed into T’ang China. It may indeed be said that the spirit of tolerance and of cosmopolitanism exhibited by T’ang Chinese is almost the exact opposite to “Han chauvinism,” arrogance, and xenophobia, which some students of Chinese history believe to have characterized the so-called “sinicization.”

“Broadly speaking, whether at the spiritual and philosophical level or at the mundane everyday level, the T’ang court and society at large seem to have well understood the futility of forced assimilation and the wisdom of “laissez-faire” in the sense of letting all ethnic and religious groups play themselves out in the same melting pot. The “final” outcome would be something that may be called “sinicization.” Biologically and culturally, the almost complete absence of reference to such ethnic terms as Hsiung-nu, Wu-huan, and Hsien-pei, seems to indicate that they had long become “sinicized” or absorbed into the enlarged Chinese nation. Religiously and philosophically, a similar phenomenon is found in the case of Buddhism. Its pre-T’ang phase is nowhere more aptly described than by the title of Eric Zurcher’s standard treatise, The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China (1959). As a result of centuries of adaptation to the Chinese milieu, Indian Buddhism finally became thoroughly “sinicized” in T’ang times, as may be evidenced by the maturation of such typically “Chinese” schools of Buddhism as the T’ien-t’ai, the Hua-yen, the Pure Land, and especially the Ch’an (Zen).

Tang Music and Dance

In the Tang Dynasty dances and music styles from outside of China were incorporated into Chinese dance and Chinese styles were passed onto other parts of the world, particularly Korea and Japan. Hundreds of young men and women were trained in dance and music at a school called the Academy of the Pear Garden. Tang poets wrote of “the dance of the rainbow skirt and feathered jacket” and described how dancers used their long silk sleeves to accentuate their hand movements. This kind of sleeve dancing was also depicted in sculptures and Buddhist cave art from the Tang period.

J. Kenneth Moore of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Music in Tang-dynasty China underwent a radical change in the sixth and seventh centuries as a result of the mass migration of peoples from Central Asia, many of whom came to the interior of China as musicians and dancers at the imperial court or in popular venues. Patronage of music at court peaked during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–55), when thousands studied at the Imperial Music Academy and hundreds of the best musicians resided at the palace." [Source: J. Kenneth Moore Department of Musical Instruments, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org]

By the A.D. 6th century pantomime dances were being performed in dynastic courts. Regarded as the precursors of Chinese theater, they blended stories, songs and dances. The performers wore masks or painted their faces. Early pieces from this genre include a performance based on the legend of Prince Lan Ling and a dance hall-style farce about a drunken wastrel called The Swinging Wife.

In the Tang Dynasty dances and music styles from outside of China were incorporated into Chinese dance and Chinese styles were passed onto other parts of the world, particularly Korea and Japan. Hundreds of young men and women were trained in dance and music at a school called the Academy of the Pear Garden. Tang poets wrote of “the dance of the rainbow skirt and feathered jacket” and described how dancer used their long silk sleeves to accentuate their hand movements. This kind of sleeve dancing was also depicted in Buddhist cave art from this period.

Foreign Entertainment, Horses and Sports

According to Silk Road Foundation: :Music, arts, and sports were part of both life and death in this affluent Tang society. They were enriched by importation. During the 8th century, Central Asiatic harpers and dancers were enormously popular in Chinese cities. Turkish folksongs were introduced and had influence on some Chinese poems. Musicians from Kucha in Central Asia probably exerted the most influence. To this day Chinese names for many instruments betray their foreign origin. [Source: “Exoticism in Tang (618-907), Silkroad Foundation”, Silk Road Foundation silk-road.com ]

Tang court playing polo

“In the 9th century, exotic literature with tales from the far West were being read and told everywhere. Storytelling and plays were popular in Tang. Many artists made living by telling fairy tales in the streets and storytellers became the most popular entertainers at court. Many years later these stories would evolve into plays.” Gambling was also popular. A crackdown on gambling included penalties of 100 lashes and death and forced tenure in the army.

“The superb power of horses from the west remains high value placed on the cavalry by the military of the Tang, which strained China's silk industry by an annual requirement of fifty million feet of silk for the purchase of horses from Turkic tribes. The six steeds of Emperor Tai-tsung are the most renowned horse in China's history, for they bore him through his military triumphs. Horses are symbols of prestigious status and a measure of wealth and power in Tang. In Tang's tombs horses figurines are of unusual quality and quantity.

“Along with horses, a western sport was introduced to China during Tang. Polo came to China in the early 7th century and became very popular sport. A combination of soccer and croquet played on horseback, the game was introduced from Persia. The emperors kept 40,000 horses in his stables, both for games and for war. Its demand for superb horsemanship made it a natural game for military men. The playground must be large, level and smooth; sticks must be fashioned by expert craftsmen. Only the rich could afford this fancy Persian sport.

“To the great learning center called the National Academy, students cam from Koguryo, Paekche, Silla, Japan, Turfan and Tibet to study Confucianism, Buddhism, literature, art and architecture. Some competed with the Chinese in civil service examinations. Some adopted Chinese names and served Tang court. In 848, for instance, an Arab named Li Yen-sheng passed the examination and became a holder of the highest academic degree. The emperor Tai-tsung employed many foreigners and many of them were trained in Chinese schools.”

Early Chinese Plays

Early dramas combined mime, stylised movement and a chorus. Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: “The chorus described the action which was enacted by dancer-actors. A play called Daimian (tai-mien) or Mask tells about a prince whose features were so soft that he was obliged to wear a terrifying mask in battle in order to scare the enemy. Later, in the Tang (T’ang) (618–907) period the play also found its way to Japan. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

“A play called Tayao niang (t’a-yao niang) or The Dancing, Singing Wife comes from the 6th century AD and is a story about domestic violence. The husband is a drunkard, who beats his poor wife. Finally, however, he is punished for his misbehaviour. From Central Asia or even from India originates a dance play called Botou (Po-t’ou) or Head for head. It is about a youth whose father was killed by a tiger. The youth, in a white mourning costume, wanders a long way over the hills and through the valleys in search for the killer tiger. During his wanderings he sings eight songs and is finally able to avenge his father's fate. **

“The play scripts of those early dance plays, which also seem to combine sung passages, are now known mainly through sources from the Tang period (618–907). Studying them is a kind of detective work where textual sources are used side by side with visual ones. Possibly some of the characteristics of later Chinese operas can be traced back to these early plays. **

“The fighting scenes appear to originate in the early martial arts systems, whereas the female movement vocabulary of later operas has retained the use of the long sleeves which dominate the female dancing tomb figurines. Even some of the themes of the early plays have continued to be essential for countless later operas, such as filial piety and other themes related to the feudal, ethical codes. **

“Speculation about how the early plays were actually performed is based on textual and visual sources. No archaic theatrical forms exist anymore in China, where the communist regime consistently destroyed forms of culture that were regarded as feudalistic. If one would like to get an idea of the early Chinese forms of performance, one should, perhaps, turn to the neighbouring cultures of Korea and Japan, which have preserved traditions from early periods when they had close contacts with imperial China and were profoundly influenced by it.” **

Palace concert

Tang Dynasty (618–907) Theater

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: “Earlier theatrical forms were further developed during the Tang period. However, the traditional ceremonial chorus dances with their large orchestras were also performed. Their stories included, among others, earlier play scripts, such as Mask and The Dancing, Singing Wife. Perhaps echoes of these kinds of ceremonial performances can still be captured in the Japanese bugaku court dances. Acrobats, jugglers and clowns, on the other hand, entertained the audience in the less serious spectacles, as had been the case in the earlier baixi or hundred entertainments shows. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

“The spectacles could reach megalomaniac proportions. Literary sources mention a performance organised in the 7th century in honour of a Turkish embassy from Central Asia. There were some 30 000 spectators. On the stage, which covered a square kilometer, acrobats, magicians and dancers demonstrated their skills. There were even grander shows. Literary sources mention a festivity with 18 000 performers and, it was told, the accompanying music was heard kilometers away. **

“With its keen interest in other cultures, the Tang court received musicians and performing arts groups from many regions. Several terracotta statuettes show Central Asian performers and the court annals record visitors from even farther away. Southeast-Asian groups were popular and it is known that performances by a Pyu group from present-day Myanmar was greatly appreciated at the court in the 7th century. At approximately the same time a group of Champa dancers, from present-day Vietnam, was employed at court. **

“Indian music was said to have accompanied a grand-scale court dance performance called Costumes decorated with feathers of the colours of the rainbow. The graceful swings and spins of the colourfully dressed dancers were greatly applauded by the court annalists. More serious scholars, however, had a critical attitude towards these kinds of mass spectacles. **

“The scholarly audience preferred intimate performances with artistic refinement. Dances were divided into two groups, energetic jian (chien) dances and softer ruan (juan) dances. The dances of the former group were often based on the martial arts or the traditions of foreign nations and they were frequently performed by male dancers. The soft ruan dances were performed by female dancers and these small-scale performances often took place at the intimate parties of connoisseurs.” **

“Adjutant Plays” and Early Story Material in the Tang Period (618-907)

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote:“At court a new form of entertainment gained popularity. It was the so-called canjun xi (ts’an-chün hsi) or the adjutant play, which probably evolved from earlier, more or less loose, clown and jester numbers. It consisted of short comic skits and featured two comic characters, a more or less dumb courtier, canjun (ts’an-chün), and a slightly cleverer character, canggu (ts’ang-ku). The “adjutant play” has been seen as a forerunner of the fixed role categories of later Chinese opera and particularly of its comic chou characters. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

“The Tang period was also the golden age for literature and many romantic stories. Buddhist legends and miracle stories were also popular. The Indian influence was strongly present, which is clearly indicated by the fact that a manuscript of the famous Indian Sanskrit play Sakuntala has been found in China. **

“The influence of the Indian epic Ramayana can be traced in the stories about the beloved (and yet anarchistic) Sun Wukong (Sun Wu-k’ung) or the Monkey King. He is a central character in originally orally transmitted stories centred on the Buddhist monk Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang), who travelled to India in order to obtain sacred Buddhist manuscripts. Later in the 16th century the stories were collected in a book called A Journey to the West, Xiyou ji (Hsi-yu chi), by Wu Chengen (Wu Ch’eng-en). The most colourful travelling companion of the monk Xuanzang is the Monkey King, who even today is the playful hero of many later operas, shadow and puppet plays, cartoons and animations.” **

Fusion of Singing, Lyrics and Prose in the Tang Period (618-907)

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “New forms of poetry rarely made their appearance in the Tang period, but the existing forms were brought to the highest perfection. Not until the very end of the Tang period did there appear the form of a "free" versification, with lines of no fixed length. This form came from the indigenous folk-songs of south-western China, and was spread through the agency of the filles de joie in the tea-houses. Before long it became the custom to string such songs together in a continuous series—the first step towards opera. For these song sequences were Song by way of accompaniment to the theatrical productions. The Chinese theatre had developed from two sources—from religious games, bullfights and wrestling, among Turkish and Mongol peoples, which developed into dancing displays; and from sacrificial games of South Chinese origin. Thus the Chinese theatre, with its union with music, should rather be called opera, although it offers a sort of pantomimic show. What amounted to a court conservatoire trained actors and musicians as early as in the Tang period for this court opera. These actors and musicians were selected from the best-looking "commoners", but they soon tended to become a special caste with a legal status just below that of "burghers".[Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: “The merging together of several literary forms such as lyrics and colloquial language seems to have happened for the first time in the didactic Buddhist stories introduced by Buddhist monks in connection with their missionary work. Verses were combined with colloquial prose in order that the ordinary audience could fully comprehend the morality of the stories. The monks, who were the storytellers, employed different devices to visualise their stories, such as picture rolls or panels, a tradition with its roots in early India, from where Buddhism was adopted. Emperor Ming Huang and the School of the Pear Garden. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

“One of the most illustrious emperors of the Tang dynasty was the emperor Ming Huang (who was called Xuanzong (Hsüan-tsang) when he came to power, 712–756). He was an active patron of the arts. At his court he had several orchestras, dancers and actors including Central Asian artists. **

“From the beginning of the Tang dynasty it was customary to have two state offices for administering the training of performers needed in official rites and ceremonies. In addition to these two offices, Ming Huang founded a third school, which trained musicians, dancers and actors. It is generally regarded as the first “theater school” in the history of China, although in reality it probably concentrated on Buddhist ceremonies. According to tradition emperor conceived this idea from a dream he had had in which he visited the moon, where he saw performances of heavenly musicians and dancers. **

“The school got its poetic name Liyuan (li-yüan) or the Pear Garden from the location in which it was established in the palace grounds. Even today actors and actresses may call themselves “the children of Pear Garden”. At the school, it is said, the training was occasionally overseen by the Emperor himself. Ming Huang is still today regarded as a kind of patron god or spirit of the art of theater and his small portrait was often placed at the lower part of the stage, in front of the audience. **

Besides the emperor Ming Huang, his dear concubine Yang Guifei (Yang Kuei-fei) is also immortalised by Chinese literature and theater. The Emperor's love for her, which nearly caused the collapse of the whole empire, is the subject of many poems and plays. Their tragic love is described in a 17th century play called Changsheng dian (Ch’ang-sheng tien) or The Palace of Eternal Love. **

“Another side of the concubine's personality is portrayed in a popular drama script called Guifei zui jiu (Kuei-fei chui chiu) or The Drunken Concubine. It relates the events of an evening when the Emperor leaves Guifei alone in order to have an encounter with another girl. The angry Guifei consoles herself by drinking and the play concentrates on describing the different stages of her drunkenness. **

Emperor Mighuang playing a flute

“In the turmoil of Chinese history, the Tang dynasty shimmers as a kind of lost Golden Age. It was a period when China was exceptionally open to outside influences. Many forms of Chinese culture, such as poetry, music and painting, produced masterpieces still regarded as classics. As has been discussed above, theater and dance also flourished. Ming Huang founded his theater school, adjutant plays experimented with fixed role categories, and, according to some scholars, Chinese dance had already attained its quintessential characteristics.” **

Tang Literature

Classical poetry reached its zenith during the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907). Fiction developed relatively late in China with the oldest known stories written in the vernacular dating back to the Tang period. Woodblock printing helped bring literature to the masses. Until the Tang Dynasty most books and documents were kept as handscrolls written by hand that were around a foot and half wide and varied in length from a few inches to several hundred feet.

Two of China's most famous poets, Li Bai and Du Fu, belonged to the age. There are over 48,900 poems penned by some 2,200 Tang authors that have survived until modern times. Skill in the composition of poetry became a required study for those wishing to pass imperial examinations, while poetry was also heavily competitive; poetry contests amongst guests at banquets and courtiers were common. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The Classical Prose Movement was spurred in large part by the writings of Tang authors Liu Zongyuan (773–819) and Han Yu (768–824), whose new prose style broke away from the poetry tradition of the 'piantiwen' style begun in the Han dynasty. Although writers of the Classical Prose Movement imitated 'piantiwen', they criticized it for its often vague content and lack of colloquial language, focusing more on clarity and precision to make their writing more direct. This guwen (archaic prose) style can be traced back to Han Yu, and would become largely associated with orthodox Neo-Confucianism. +

Short story fiction and tales were also popular during the Tang, one of the more famous ones being Yingying's Biography by Yuan Zhen (779–831), which was widely circulated in his own time and by the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) became the basis for plays in Chinese opera. Timothy C. Wong places this story within the wider context of Tang love tales, which often share the plot designs of quick passion, inescapable societal pressure leading to the abandonment of romance, followed by a period of melancholy. Wong states that this scheme lacks the undying vows and total self-commitment to love found in Western romances such as Romeo and Juliet, but that underlying traditional Chinese values of inseparableness of self from one's environment (including human society) served to create the necessary fictional device of romantic tension. +

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The Tang literature shows the co-operation of many favourable factors. The ancient Chinese classical style of official reports and decrees which the Toba had already revived, now led to the clear prose style of the essayists, of whom Han Yu (768-825) and Liu Tsung-yuan (747-796) call for special mention. But entirely new forms of sentences make their appearance in prose writing, with new pictures and similes brought from India through the medium of the Buddhist translations. Poetry was also enriched by the simple songs that spread in the north under Turkish influence, and by southern influences. The great poets of the Tang period adopted the rules of form laid down by the poetic art of the south in the fifth century; but while at that time the writing of poetry was a learned pastime, precious and formalistic, the Tang poets brought to it genuine feeling. Widespread fame came to Li T'ai-po (701-762) and Tu Fu (712-770); in China two poets almost equal to these two in popularity were Po Chu-i (772-846) and Yuan Chen (779-831), who in their works kept as close as possible to the vernacular. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

See Separate Article on TANG POETRY

Wood Block Printing: from Tang-Era China

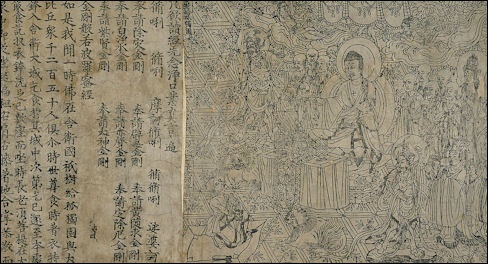

The Chinese are credited with inventing wood block printing in the A.D. 3rd century, and printing presses in the 11th century. Block printing on paper was widely developed in the Tang dynasty. The emperor's library in the 7th century held about forty thousand manuscript rolls. Before giving China full credit for inventing printing it must pointed out the wood-block printing invented by the Chinese was very different from the movable type printing used by Gutenberg to print his famous Bible in the 15th century. "Making repeated images for printing textiles from a carving on wood was an ancient folk art," Daniel Boorstin in The Discoverers. "At least as early as the third century the Chinese had developed an ink that made clear and durable impressions from these wood blocks. They collected the lamp black from burning oils or woods and compounded it into a stick, which then dissolved to the black liquid that we call India ink." [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin |=|]

Diamond sutra

The world's oldest surviving printed documents, a miniature Buddhist dharani sutra unearthed at Xi'an in 1974, dates roughly from 650 to 670. A copy of the Diamond Sutra found at Dunhuang is the earliest surviving full-length book printed at regular size, complete with illustrations embedded within the text and dated precisely to 868. Among the earliest documents to be printed were Buddhist texts as well as calendars, the latter essential for calculating and marking which days were auspicious and which days were not. [Source: Wikipedia]

The world's oldest surviving book, the Diamond Sutra, was printed with wooden blocks in China in A.D. 868. It consists of Buddhist scriptures printed on seven 2½-foot-long, one-foot-wide sheets of paper pasted together into one 16-foot-long scroll. Part of the Perfection of Wisdom text, a Mahayanist sermon preached by Buddha, it was found in cave in Gansu Province in 1907 by the British explorer Aurel Stein, who also found well-preserved 9th century silk and linen paintings.

The idea for wood-block printing on paper began when someone decided to take the handle off a wooden stamp so that printing surface could be placed face up on a table. A sheet of paper then could be laid on the inked block, rubbed with a brush, to produce a print. The making of large woodcuts became possible when several of these "wooden stamps" were placed side by side. Buddhism played an instrumental role in the development of block printing in China in the A.D. 7th century. Buddhists believe they can earn "merit" (brownie points on the path to Nirvana) by duplicating the image of Buddha and repeating sacred texts. The more images or texts a Buddhist makes the more merit he earns. Buddhists use rubbings from stones, seals, stencils and small wooden stamps to make images over and over. For them printing is perhaps the easiest, most efficient and most cost effective way to earn merit. The earliest examples of Chinese printing were destroyed during a crackdown on Buddhism in 845 when temples were destroyed and a quarter of a million nuns and monks were forced to flee their monasteries. |=|

Chinese ideograms are not well suited for movable type. There are so many Chinese characters it is difficult to make multiple copies of them and to categorize them in a way that is easy to retrieve. Roman letters are better suited for movable type because there are many fewer letters. Chinese ideograms have a couple of advantages over Roman letters when it comes to printing. Their intricate forms are more interesting for carvers to make and their large size makes them easier to align on a page and grasp and put into place with the fingers. |=|

Impact of Wood Block Printing

Block printing made the written word available to vastly greater audiences. As a result of the much wider distribution and circulation of reading materials, the general populace were for the first time able to purchase affordable copies of texts, which correspondingly led to greater literacy. While the immediate effects of woodblock printing did not create a drastic change in Chinese society, in the long term, the accumulated effects of increased literacy enlarged the talent pool to encompass civilians of broader social-economic circumstances and backgrounds, who would be seen entering the imperial examinations and passing them by the later Song dynasty. [Source: Wikipedia]

In Imperial times, the Chinese preferred handwritten calligraphy over printing for important texts. Printing was used by those who could not afford anything better. In 932 a Chinese prime minister wrote: "We have seen... men from Wu and Shu who sold books that were printed from blocks of wood. There were many different texts, but there were among them no orthodox Classics [of Confucianism]. If the Classics could be revised and thus cut in wood and published, it would be a very great boon to the study of literature."

The revival of Confucianism during the Chinese Renaissance of the Song dynasty (A.D. 960-1127) is partly attributed to the printing of Confucian texts which helped spread the word of the philosophy to a greater number of people. By the end of the 10th century scholars printed the first of the great Chinese dynastic histories, consisting of several hundred volumes, and Buddhist monks printed the Tripitaka, the whole Buddhist canon with 5,048 volumes and 130,000 pages. In 1019, the 4,000-volume Taoist cannon was printed. In the 11th century Muslims in China printed calendars and almanacs while the Koran continued to be made by hand.

The commercial success, profitability and astonishing low price offered by woodblock were pointed out by a British observer in China at the end of the nineteenth century: “We have an extensive penny literature at home, but the English cottager cannot buy anything like the amount of printed matter for his penny that the Chinaman can for even less. A penny Prayer-book, admittedly sold at a loss, cannot compete in mass of matter with many of the books to be bought for a few cash in China. When it is considered, too, that a block has been laboriously cut for each leaf, the cheapness of the result is only accounted for by the wideness of sale. [Source: Barrett, Timothy Hugh, “The Woman Who Discovered Printing,” Yale University Press, 2008]

Although Bi Sheng later invented the movable type system in the 11th century, Tang dynasty style woodblock printing would remain the dominant mode of printing in China until the more advanced printing press from Europe became widely accepted and used in East Asia. However it was not Gutenberg's letterpress that made the decisive breakthrough for Western methods in China as it is commonly believed, but lithography, a nineteenth century technological marvel almost wholly forgotten in Europe. +

Encyclopedias and Historians from Tang Dynasty

There were large encyclopedias published in the Tang. The Yiwen Leiju encyclopedia was compiled in 624 by the chief editor Ouyang Xun (557–641) as well as Linghu Defen (582–666) and Chen Shuda (d. 635). The encyclopedia Treatise on Astrology of the Kaiyuan Era was fully compiled in 729 by Gautama Siddha (fl. 8th century), an ethnic Indian astronomer, astrologer, and scholar born in the capital Chang'an. +

Chinese geographers such as Jia Dan wrote accurate descriptions of places far abroad. In his work written between 785 and 805, he described the sea route going into the mouth of the Persian Gulf, and that the medieval Iranians (whom he called the people of Luo-He-Yi) had erected 'ornamental pillars' in the sea that acted as lighthouse beacons for ships that might go astray. Confirming Jia's reports about lighthouses in the Persian Gulf, Arabic writers a century after Jia wrote of the same structures, writers such as al-Mas'udi and al-Muqaddasi. The Tang dynasty Chinese diplomat Wang Xuance traveled to Magadha (modern northeastern India) during the 7th century. Afterwards he wrote the book Zhang Tianzhu Guotu (Illustrated Accounts of Central India), which included a wealth of geographical information. +

Many histories of previous dynasties were compiled between 636 and 659 by court officials during and shortly after the reign of Emperor Taizong of Tang. These included the Book of Liang, Book of Chen, Book of Northern Qi, Book of Zhou, Book of Sui, Book of Jin, History of Northern Dynasties and the History of Southern Dynasties. Although not included in the official Twenty-Four Histories, the Tongdian and Tang Huiyao were nonetheless valuable written historical works of the Tang period. The Shitong written by Liu Zhiji in 710 was a meta-history, as it covered the history of Chinese historiography in past centuries until his time. The Great Tang Records on the Western Regions, compiled by Bianji, recounted the journey of Xuanzang, the Tang era's most renowned Buddhist monk. +

Other important literary offerings included Duan Chengshi's (d. 863) Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang, an entertaining collection of foreign legends and hearsay, reports on natural phenomena, short anecdotes, mythical and mundane tales, as well as notes on various subjects. The exact literary category or classification that Duan's large informal narrative would fit into is still debated amongst scholars and historians. +

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021