PAINTING AND CHINESE SCHOLAR-OFFICIALS

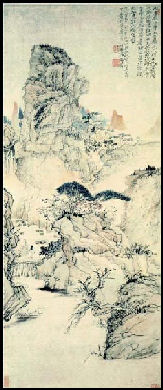

Leisurely Sound of

Mountains and Spring

by Shi Tao

Unlike artists in the West who were either skilled craftsmen paid by the hour or professional artists who were commissioned to produce unique works of art, Chinese artists were mostly amateur scholar gentlemen "following revered ancients in harmony with forces of nature." Calligraphy and painting were seen as scholarly pursuits of the educated classes, and in most cases the great masters of Chinese art distinguished themselves first as government officials, scholars and poets and were usually skilled calligraphers. Sculpture, which involved physical labor and was not a task performed by gentlemen, never was considered a fine art in China.

Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “By the eleventh century, a good hand was one criterion—together with a command of history and literary style—that determined who was recruited into the government through civil service examinations. Those who succeeded came to regard themselves as a new kind of elite, a meritocracy of "scholar-officials" responsible for maintaining the moral and aesthetic standards established by the political and cultural paragons of the past. It was their command of history and its precedents that enabled them to influence current events. It was their interpretations of the past that established the strictures by which an emperor might be constrained. And it was their poetry, diaries, and commentaries that constituted the accounts by which a ruler would one day be judged. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Scholar-official painters most often worked in ink on paper and chose subjects—bamboo, old trees, rocks—that could be drawn using the same kind of disciplined brush skills required for calligraphy. This immediately distinguished their art from the colorful, illusionistic style of painting preferred by court artists and professionals. Proud of their status as amateurs, they created a new, distinctly personal form of painting in which expressive calligraphic brush lines were the chief means employed to animate their subjects. Another distinguishing feature of what came to be known as scholar-amateur painting is its learned references to the past. The choice of a particular antique style immediately linked a work to the personality and ideals of an earlier painter or calligrapher. Style became a language by which to convey one's beliefs.\^/

“Since scholar-artists employed symbolism, style, and calligraphic brushwork to express their beliefs and feelings, they left the craft of formal portraiture to professional artisans. Such craftsmen might be skilled in capturing an individual's likeness, but they could never hope to convey the deeper aspects of a man's character. Integrating calligraphy, poetry, and painting, scholar-artists for the first time combined the "three perfections" in a single work. In such paintings, poetic and pictorial imagery and energized calligraphic lines work in tandem to express the mind and emotions of the artist. \^/

See Separate Articles: CHINESE PAINTING: THEMES, STYLES, AIMS AND IDEAS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; ART FROM CHINA'S GREAT DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTING FORMATS AND MATERIALS: INK, SEALS, HANDSCROLLS, ALBUM LEAVES AND FANS factsanddetails.com ; GREAT AND FAMOUS CHINESE PAINTINGS factsanddetails.com ; SUBJECTS OF CHINESE PAINTING: INSECTS, FISH, MOUNTAINS AND WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTINGS OF GHOSTS AND GODS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TAOIST ART: PAINTINGS OF GODS, IMMORTALS AND IMMORTALITY factsanddetails.com ; PAINTING FROM THE TANG, SONG, YUAN, MING AND QING DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; TANG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ANIMAL, RELIGIOUS AND FIGURE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; YUAN ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; MING DYNASTY PAINTING AND ITS FOUR GREAT MASTERS factsanddetails.com ; QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Painting” by James Cahill (Rizzoli 1985) Amazon.com; “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” by Richard M. Barnhart, et al. (Yale University Press, 1997); Amazon.com; “How to Read Chinese Paintings” by Maxwell K. Hearn (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008) Amazon.com; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Literati Versus Academic Chinese Painters

According to the literati ideal in imperial and traditional China an educated gentlemen aspiring to government service should also be an accomplished poet and painter. Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “ By looking at the way that the members of the governing elite approached the art of painting, we can gain some further insight into the way in which they conceived and tried to live up to the literati ideal. The key division that we will emphasize here is one between men who were called "academic" painters, and those who were seen as painters in the literati tradition. What's the difference? [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University]

"Academic painters" were highly skilled craftsmen, who aimed to achieved marvelous effects through their use of colors, realistic or highly conventional representations of people or things, spectacular detail, applications of shiny gold leaf, and so forth. The Imperial court employed many such men, and others made their way in the world by selling their paintings to wealthy patrons and customers. Academic painters were professionals, both in their virtuoso skills, and in the fact that they depended on permanent employment as painters, or on selling their paintings to live. While many of these men were educated to some degree, few possessed the literary background of a literatus, and none made their way in life fulfilling the Confucian ideal of governmental service. "Literati painters," on the other hand, were amateurs — they painted as a means of self-expression, much the same way they wrote poetry; both forms were inheritances from the Neo-Daoist era of the Six Dynasties. While many fewer literati were accomplished painters than were poets (and painting was never an aspect of the exams), in every major place in China there were always many literati who either painted on the side, while playing the role of scholar-officials, or who, through wealth, could afford to devote themselves fully to the art of painting.

“Literati painting was conceived as mode through which the Confucian junzi (noble person) expressed his ethical personality. It was much less concerned with technical showiness. Literati painters specialized in plain ink paintings, sometimes with minimal color. They lay great emphasis on the idea that the style with which a painter controlled his brush conveyed the inner style of his character — brushstrokes were seen as expressions of the spirit more than were matters of composition or skill in realistic depiction. /+/ While literati poetry developed fully during the Tang Dynasty on the basis of long Six Dynasties preparation, painting did not become central to literati until later. Although we hear of famous poet-painters of the Tang, because their works have not survived it is difficult to know to what degree their art differed from academic painting. During the late Song, however — that is, after about 1200 — literati and academic painting become two distinct streams. Interestingly, although academic paintings were often far more skilled in technique, many felt — and still feel — that the "amateur" ink paintings of the literati are the highest form of art in China. The most important of the painters we will look at is a man named Shen Zhou (1427-1509), who lived during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).” His approach to his art illustrates many key facets of the Confucian-Daoist literati ideal, translated into an approach to painting.

Literati Painters

What exactly was required to be a literati painter is a matter of some debate."In ancient China a learned man was expected to take government office," Zhang told the China Daily. "That explains why literati painting was at times called, rather strangely to modern ears, 'paintings by the officer class'. In fact many learned men did not end up being office holders. Some might have failed the royal examinations, and some refused to serve a new regime."Zhao Xu And Su Qiang wrote in the China Daily:“Apart from that, during the Qing Dynasty, with education becoming accessible to an increasing number of people, there were less government posts than qualified candidates. So to regard someone as a literati painter by dint of a government post he held is absurd. [Source: Zhao Xu And Su Qiang, China Daily, December 19, 2015]

“Further complicating the picture is that there was never a set style for literati painting. Some well-known painter-poets had personal tastes that inclined more towards a subtle, delicate court style, practiced by professional painters on the emperor's payroll. And on rare occasions, professional painters with little education, Qiu Ying, for example, produced works that amounted to visual poetry. Both have traditionally been considered literati painters.

“Yin Jinan, an art historian and professor at the Central Academy of Art in Beijing, has suggested a new way for making such delineations. "The word literati implies a group," he wrote in an essay. "A man could be called a literati painter if he painted and socialized with members of the group. Neither style nor educational level alone could be considered a deciding factor." In other words, to be remembered as a literati painter, one had to stay within the circle.

“Yang has a very different take on the question. "Today, people tend to emphasize the difference between professional and literati painting, pitting one against the other. In fact, the boundary has always been very fuzzy. Among most literati painters there was no lack of respect for their professional counterparts." Yang cites as an example Tang Yin (1470-1524), a renowned literati painter who studied for years under a professional painter.

“And some probably had an intimate understanding of the hand-to-mouth existence of many low-level professional painters, brought on either by personal misfortune or as a result of what was happening at the time."Literati painters were forced to step into the same marketplace as their professional counterparts, where they had to outwit the anonymous imitators to defend their own financial interests," Zhang says. One example was literati painters' use of a seal, often inscribed with their by name or motto. While the tiny square of scarlet red formed a delectable contrast with the inky brushworks, it also helped the painter to announce himself, and the buyers to recognize his painting.

“Reflecting on the fact that Chinese painting history over the past millennium has largely been the history of literati painting, Yang says this was more or less inevitable. "It's not unlike today: While painter-artisans make up the bulk of the group, it is only a handful of masters whom history will eventually remember. In the case of literati painters, they were the ones who wrote the history." James Cahill, internationally renowned Chinese art historian and collector, once wrote that Chinese painters, by inscribing and stamping their works, knowingly added a "self" onto the painting and therefore avoided the possibility of creating the visual illusion loved by their Western counterparts. Instead of being led directly into another world, the viewers are constantly reminded of the painter's presence. Commenting on this phenomenon, Yang says: "The literati painters, steeped in ancient Chinese philosophy, believed in the unity of man and nature. They found a place for themselves in their paintings of mountains and rivers because that's where they thought they belonged."

Zhao Mengfu: the Consummate Chinese Scholar-Painter

Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Zhao Mengfu epitomized the new artistic paradigm of the scholar-amateur. A scholar-official by training, he was also a brilliant calligrapher (1989.363.30) who applied his skill with a brush to painting. Intent on distinguishing his kind of scholar-painting from the work of professional craftsmen, Zhao defined his art by using the verb "to write" rather than "to paint." In so doing, he underscored not only its basis in calligraphy but also the fact that painting was not merely about representation—a point he emphasized in his Twin Pines, Level Distance (1973.120.5) by adding his inscription directly over the landscape. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Zhao was a consummate scholar, and his choice of subject and painting style was carefully considered. Because the pine tree remains green through the winter, it is a symbol of survival. Because its outstretched boughs offer protection to the lesser trees of the forest, it is an emblem of the princely gentleman. For recluse artists of the tenth century, the pine had signified the moral character of the virtuous man. Zhao, having recently withdrawn from government service under the Mongols, must have chosen to "write" pines in a tenth-century style as a way to express his innermost feelings to a friend. His painting may be read as a double portrait—a depiction of himself and also of the person to whom it was dedicated.\^/

“As the arbiters of history and aesthetic values, scholars had an immense impact on taste. Even emperors came to embrace scholarly ideals. Although some became talented calligraphers and painters (1981.278), more often they recruited artists whose images magnified the virtues of their rule. Both the court professional and the scholar-amateur made use of symbolism, but often to very different ends. While Zhao Mengfu's pines may reflect the artist's determination to preserve his political integrity, a landscape painting by a court painter might be read as the celebration of a well-ordered empire. A scholar-painting of narcissus reflects the artist's identification with the pure fragrance of the flower, a symbol of loyalty, while a court painter's lush depiction of orchids was probably intended to evoke the sensuous pleasures of the harem. The key distinction between scholar-amateur and professional painting is in the realization of the image: through calligraphically abbreviated monochrome drawing on paper or through the highly illusionistic use of mineral pigments on silk.\^/

Banished Chinese Scholar-Officials

Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “When an emperor neglected the advice of his officials, was unjust or immoral, scholar-officials not infrequently resigned from government and chose to live in retirement. Such an action had long been understood as a withdrawal of support, a kind of silent protest in circumstances deemed intolerable. Times of dynastic change were especially fraught, and loyalists of a fallen dynasty usually refused service under a new regime. Scholar-officials were at times also forced out of office, banished as a result of factionalism among those in power. In such cases, the alienated individual might turn to art to express his beliefs. But even when concealed in symbolic language, beliefs could incite reprisals: the eleventh-century official Su Shi, for example, was nearly put to death for writing poems that were deemed seditious. As a result, these men honed their skills in the art of indirection. In their hands, the transcription of a historical text could be transformed into a strident protest against factional politics (1988.363.4), illustrations to a Confucian classic became a stinging indictment of sanctimonious or irresponsible behavior (1996.479). Because of their highly personal nature, such works were almost always dedicated to a close friend or kindred spirit and would have been viewed only by a select circle of likeminded individuals. But since these men acted as both policy makers and the moral conscience of society, their art was highly influential. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Tang Dynasty Painters

Celebrated Tang-era painters included Han Gan (706-783), Zhang Xuan (713-755), and Zhou Fang (730-800). The court painter Wu Daozi (active ca. 710–60) was famous for his naturalist style and vigorous brushwork. Wang Wei (701–759) was admired as a poet, painter and calligrapher. who said "there are paintings in his poems and poems in his paintings."

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The most famous Chinese painter of the Tang period is Wu Daozi, who was also the painter most strongly influenced by Central Asian works. As a pious Buddhist he painted pictures for temples among others. Among the landscape painters, Wang Wei (721-759) ranks first; he was also a famous poet and aimed at uniting poem and painting into an integral whole. With him begins the great tradition of Chinese landscape painting, which attained its zenith later, in the Song epoch. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

It was from the Six Dynasties (222-589) to the Tang dynasty (618-907) that the foundations of figure painting were gradually established by such major artists as Gu Kaizhi (A.D. 345-406) and Wu Daozi (680-740). Modes of landscape painting then took shape in the Five Dynasties period (907-960) with variations based on geographic distinctions. For example Jing Hao (c. 855-915) and Guan Tong (c. 906-960) depicted the drier and monumental peaks to the north while Dong Yuan (?–962) and Juran (10th century) represented the lush and rolling hills to the south in Jiangnan. In bird-and-flower painting, the noble Tang court manner was passed down in Sichuan through the style of Huang Quan (903–965), which contrasts with that of Xu Xi (886-975) in the Jiangnan area. The rich and refined style of Huang Quan and the casual rusticity of Xu Xi's manner also set respective standards in the circles of bird-and-flower painting. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

See Separate Articles TANG DYNASTY ART: PAINTING, CALLIGRAPHY AND BUDDHIST CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

Song Dynasty Painters and Painting Schools

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In the Northern Song period (960-1279), such artists as Fan Kuan, Guo Xi, and Li Tang established a new paradigm in landscape painting with their towering and majestic manner of monumental peaks. With an emphasis on sketching from life, the bird-and-flower paintings of such artists as Huang Jucai and Cui Bo overflow with life and spirit. Emperor Huizong formed a Painting Academy system that accelerated the pursuit of lyricism while providing an important goal for painting. And even by the end of the Southern Song (1127-1279), this painting style continued to flourish. Furthermore, such scholar-artists as Wen Tong and Su Shi, who did not seek formal likeness in representation, paved the way for the formation of a new realm in Chinese art: literati painting. Li Gonglin was a Song dynasty painter who gave form to the ideal of painting as a reflection of the artist's mind and an expression of deeply held values. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Some scholars say that Chinese painting reached its pinnacle during the Song dynasty under Huizong (Hui Tsung,1100-1126), an emperor who was much better painter than ruler. He set up and taught at China's first academy of painting and amassed a collection of 6,400 painting by 231 masters. Chinese artists often collected the works of other artists as sources of inspiration. Ebrey wrote: “During the Northern Song, and especially during the reign of Huizong, the standing of court painters was raised and the court painting academy became an educational institution; court painters were ranked, tested, and rewarded in imitation of the way civil service officials were. Courtly styles throughout the Song and Yuan period were characterized by technical finesse and close observation. Court artists spent part of their time copying old masterpieces, a practice that served the practical purposes of preserving compositions but also helped maintain high technical standards.”

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “While the Song period was one of perfection in all fields of art, painting undoubtedly gained its highest development in this time. We find now two main streams in painting: some painters preferred the decorative, pompous, but realistic approach, with great attention to the detail. Later theoreticians brought this school in connection with one school of meditative Buddhism, the so-called northern school. Men who belonged to this school of painting often were active court officials or painted for the court and for other representative purposes. One of the most famous among them, Li Lung-mien (ca. 1040-1106), for instance painted the different breeds of horses in the imperial stables. He was also famous for his Buddhistic figures. Another school, later called the southern school, regarded painting as an intimate, personal expression. They tried to paint inner realities and not outer forms. They, too, were educated, but they did not paint for anybody. They painted in their country houses when they felt in the mood for expression. Their paintings did not stress details, but tried to give the spirit of a landscape, for in this field they excelled most. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

See Separate Articles SONG DYNASTY ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY LANDSCAPEPAINTING factsanddetails.com

Zhao Mengfu and the Four Yuan Masters

The Four Masters of the Yuan dynasty were Huang Gongwang (1269-1354), Wu Zhen (1280–1354), Ni Zan (1306-1374), and Wang Meng (1308 – 1385). They were active during the Yuan dynasty but given their designation in the Ming dynasty, during which and after they were deeply revered as promulgates the “literati” tradition of painting”, which valued individual expression and learning over outward representation and immediate visual appeal. [Source: Wikipedia]

Huang Gongwang and Wu Zhen belonged to the early generation of artists in the Yuan period. They consciously emulated the work of ancient masters, especially the pioneering artists of the Five Dynasties period, such as Dong Yuan and Juran, who rendered landscape in a broad, almost Impressionistic manner, with coarse brushstrokes and wet ink washes. The two younger Yuan masters, Ni Zan and Wang Meng respected by the the work of their predecessors their styles were very different as well as different from each other. Ni Zan's style has been called "restrained thinness" while Wang Meng is known for his "embroidered richness". The work of the Four Masters encouraged experimentation and the use of novel brushstroke techniques.

Wu Zhen (style name Zhongkui; sobriquets Meihua daoren, Meishami) was a native of Weitang within Jiaxing, Zhejiang. He was good at poetry, cursive script, and painting landscapes, bamboo and rocks, and ink flowers. In landscape painting, he followed the Five Dynasties artist Juran and and, in ink bamboo, Wen Tong of the Song dynasty,absorbing the styles of previous masters to establish his own personal manner and creating marvelous works to become one of the Four Yuan Masters.

Wang Meng, a native of Wu-hsing (modern Hu-chou, Zhejiang), was a grandson of the famous artist Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322). he also was taught by Huang Gongwang while learning from such figures as Ni Zan. He also stood on his own, becoming one of the Four Yuan Masters. In the early Ming, Wang Meng was implicated in the case of Hu Wei-yung and subsequently died in prison. His painting followed the styles of Wang Wei (701-761), Tung Yuan (fl. 1st half of 10th century), and Chu-jan (10th century), and he established a style of his own, becoming one of the Four Great Masters of the Yuan along with Huang Kung-wang (1269-1354), Wu Chen (1280-1354), and Ni Zan (1301-1374). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Even though he wasn't one of the Four Yuan Masters, Zhou Mengfu was perhaps the greatest painter in the Yuan Dynasty. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ In the Yuan dynasty Zhao Mengfu and the Four Yuan Masters highlighted the spirit harmony and a new sense of brush and ink in their works, firmly establishing literati painting as one of the unwavering stalwarts of Chinese art. Zhao Mengfu, a member of the Sung imperial clan, resided in Wu-hsing, Zhejiang. His style name was Tzu-ang, and his sobriquet was Sung-hsueh tao-jen. In the following Yuan dynasty, he also served as a scholar in the Han-lin Academy, and was enfeoffed as Duke of Wei. His poetry and prose are pure and lofty, while his great achievements in calligraphy and painting have served as models for generations., He was famed as a revivalist in painting, which he often did with a calligraphic touch. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

See Separate Articles YUAN ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ;

Four Masters of the Ming Dynasty

The Four Masters of the Ming dynasty are a traditional grouping in Chinese art history of four famous Chinese painters of the Ming dynasty. The painters are Shen Zhou (1427-1509), Wen Zhengming (1470-1559), Tang Yin (1470-1523), and Qiu Ying (c.1494-c.1552). Shen Zhou and Wen Zhengming were leaders in the Wu School. Their styles and subject matter were varied. Shen and Wen personified the Wu School ideal of the literati gentleman artist, while Tang and Qiu were accomplished examples of the Suzhou professional class of painters. Qiu was solely a painter; the other three developed distinct styles of painting, calligraphy, and poetry. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Four Masters of the Ming dynasty were approximate contemporaries, friends when their lives overlapped and were intimately familiar with each other's work. Shen Zhou was the teacher of Wen Zhengming. The other two studied with Zhou Chen. Their family backgrounds were different. Tang Yin was born into a rich merchant family, Wen Zhengming was born into a bureaucratic family and was himself a government official. Qiu Ying was a craftsman of dyes and lacquers. Shen Zhou was one of the main founders of the Wu School of painting. Shen's early mentor was Du Qiong, and Shen's paternal grandfather was a friend of Wang Meng, an artist of the late Yuan dynasty. Shen's father and uncle were both painters.

Both Shen Zhou and Qiu Ying were most accomplished in shan shui painting, and they were well-versed in the painting style of the imperial court. Tang Yin was accomplished in nearly all styles of traditional Chinese painting. Wen Zhengming was accomplished in blue-green shan shui painting and the gongbi style. Zhou Chen was an important coach in Tang's early career, while Qiu Ying was self-taught. Tang Yin later became a character in historical fiction and is very well known in popular culture.[3]

See Separate Article MING DYNASTY PAINTING AND ITS FOUR GREAT MASTERS factsanddetails.com

Wang Hui: China’s Great 17th Century Landscape Painter

Wang Hui (1632-1717) is the most celebrated painter of late seventeenth-century China. Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: He “played a key role in reinvigorating past traditions of landscape painting and establishing the stylistic foundations for the imperially sponsored art of the Qing court. Drawing upon his protean talent and immense ambition, Wang developed an all-embracing synthesis of historical landscape styles that constituted one of the greatest artistic innovations of late imperial China. Wang's stature was confirmed in 1698, when the emperor bestowed upon him the encomium "Landscapes Clear and Radiant." [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Wang's landscape art was not based on direct encounters with nature; rather, he sought to achieve a spiritual resonance with an orthodox lineage of great masters while creatively transforming their styles. Engaging in an inventive dialogue with the past, Wang evoked the stylistic personas of earlier masters while making works that were distinctly his own. Wang's paintings not only pay homage to his gifted predecessors but demand to be judged in comparison to them.\^/

“Traditional accounts of Wang present him as a virtual reincarnation of the ancient masters, but in modern times this tribute has not been viewed as a compliment. As revolutionary China increasingly rejected its past and idealized the new, Wang's art was criticized as backward-looking and circumscribed by convention. Some Western scholars adopted the same view, labeling Wang's paintings as "art-historical art" and disparaging him as a mere copyist whose works only restate earlier pictorial ideas. But like a master calligrapher whose writing is a personal synthesis of earlier models, Wang's paintings combine disparate stylistic influences in totally new and inspired ways to make each "performance" spontaneous and fresh. So while his sources are recognizable, his evocations are never dry or stale; they always depart from their model by ingeniously modifying the composition, reworking the structure, and revitalizing the brushwork in ways that are sophisticated and bold. Wang did not merely imitate the past, he reinvented it.” \^/

Wang Hui Inspirations and Mentors

Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Wang Hui was deeply inspired by the vast panoramas and rich descriptive detail of early monumental landscape painting as well as by the more intimate and abstract modes of early literati painting. Thanks to his connections with many of the leading collectors of his day, he was able to study examples of early landscape painting firsthand. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“During his early career, Wang Hui focused his energies on mastering the dynamic compositions and calligraphic brush mannerisms of a select group of fourteenth-century scholar-artists whose expressive reinterpretations of tenth- and eleventh-century models had revolutionized painting. Drawing on the scholar-official aesthetic of the late Northern Song, these Yuan literati artists explored the possibilities of calligraphic abstraction, replacing forms that were essentially representational with forms that were essentially expressive and self-reflective. Early Ming scholar-artists emulated these styles, transforming them into sets of simplified brush conventions. But as the Ming dynasty progressed, these styles became increasingly devoid of expressive meaning. The revitalization of these styles became a primary objective of Wang Hui.\^/

“Under the mentorship of Wang Shimin (1592–1680), Wang Hui was thoroughly versed in the art and theories of Wang Shimin's teacher Dong Qichang (1555–1636). Dong became Wang Shimin's tutor around 1606, and fostered the young man's passion for collecting ancient paintings. Over the next twenty years, Dong passed on many of the finest works from his own collection to Wang Shimin, who became his leading disciple.\^/

“Dong Qichang, who had both the eye of a painter and the knowledge of a connoisseur and collector, formulated a systematic theory of literati painting. According to Dong, the true path to innovation was through correspondence with—and transformation of—the old, thus endowing it with new significance: "Copying [a style] is easy; spiritual communion [with the ancients] is difficult." Complaining that late Ming professional painting had become "sweet, vulgar, fragmented and flat," Dong sought to create a revolutionary theory of artistic renewal or reintegration by reasserting the primacy of calligraphic brushwork and form over descriptive representation: "If one considers the uniqueness of scenery, then a painting is not the equal of real landscape; but if one considers the wonderful excellence of brush and ink, then landscape can never equal painting." \^/

Dong's new "orthodox" theory of landscape art was closely linked to his efforts to reenvision an ancient "true" and "correct" lineage of scholar-amateurs. In his theory of the Northern and Southern Schools of painting, Dong viewed the Tang-dynasty poet and amateur painter Wang Wei (701–761) as the founding "patriarch" of the Southern School. This tradition was developed by the Southern Tang painters Dong Yuan (active 930s–60s) and Juran (active ca. 960–85), who were followed by Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322) and the Four Late Yuan Masters: Huang Gongwang (1269–1354), Wu Zhen (1280–1354), Ni Zan (1306–1374) and Wang Meng (ca. 1308–1385).\^/

Wang Hui’s Life and the Development of His Style

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “ Born in Yushan (Mount Yu), a village near Changshu, north of Suzhou (modern Jiangsu Province), Wang Hui was a child prodigy whose artistic talents were first recognized at the age of fifteen when he was introduced to the preeminent Orthodox master Wang Shimin. Wang was so impressed by the young man's brilliance that he promptly invited him to study and copy all the ancient masterworks at his family villa in Taicang, where he spent years as a guest and retainer. Throughout the 1660s and 1670s, Wang Hui maintained a close relationship with Wang Shimin, who helped him gain access to many of the finest private collections in the region, but in time these collectors became more important patrons. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“In the early 1660s, Wang concentrated on mastering the calligraphic idioms of the late Yuan masters Huang Gongwang and Wang Meng, in which the kinetic "hemp-fiber" texture strokes are carriers of the "breath-force" movements of the composition. By the late 1660s, however, Wang began to explore the more descriptive idioms of the Song-dynasty masters. Expanding on Dong Qichang's idea of transforming landscapes into calligraphic abstractions, Wang Hui wrote: "I must use the brush and ink of the Yuan to move the peaks and valleys of the Song, and infuse them with the breath-resonance of the Tang. I will then have a work of the Great Synthesis." Searching for his Great Synthesis, Wang Hui also embraced the whole spectrum of painting, from the calligraphic and abstract to the descriptive and decorative.\^/

“In the late 1660s and early 1670s, Wang Hui began to systematically expand his repertoire of ancient styles in order to achieve a Great Synthesis as exemplified in several albums that showcase Wang's creative reinterpretations of a broad range of earlier styles. This is the period when Wang began to explore the potential of the infinitely expandable handscroll format. Wang's The Colors of Mount Taihang, dated 1669, is one of his earliest essays at reviving the monumental style of the tenth and eleventh centuries. In it, Wang successfully reconfigures the towering vertical mountains of the tenth-century master Guan Tong into the horizontal format through the use of thrusting mountain forms and vigorous brushwork that powerfully convey the tectonic forces of nature. \^/

“Wang Hui's approach to painting is analogous to that adopted by calligraphers, who begin by imitating a specific set of earlier models, then gradually expand their repertoire until they are able to incorporate stylistic influences from various masters, eventually arriving at a personal synthesis that is uniquely their own. For Wang Hui, each earlier master was similarly envisioned as a set of "ideographic form-types"—foliage and texture patterns and compositional solutions—that defined that artist's style. The competent replication of these solutions was only the beginning, the ultimate goal being the attainment of what Dong Qichang called a "spiritual correspondence with the model through creative metamorphosis." \^/

Wang Hui's Panoramic Landscapes: "Mountains and Rivers without End"

Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “ After the suppression of the Revolt of the Three Feudatories in 1681 and the annexation of Taiwan in 1683, the Kangxi reign (1662–1722) entered a time of peace and prosperity. The Kangxi emperor embarked in 1684 on his first Southern Inspection Tour to consolidate Manchu rule over the south as well as to celebrate the beginning of a new era. Wang Hui responded rapidly to this changed political and cultural environment. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“During the 1680s, Wang Hui undertook to paint ever longer handscrolls in which he successfully integrated varied regional terrain features and landscape styles. Wang also expanded his pictorial repertoire beyond calligraphic brushwork to include more intricately rendered architectural elements and figures and a more naturalistic application of colors and ink washes to suggest the veiling effects of moisture-laden atmosphere.\^/

“In 1684, just months before the Kangxi emperor's first tour to southern China, Wang Hui painted a sixty-foot-long handscroll for the high official Wu Zhengzhi (1618–1691). The painting revives the grand panoramic landscape style of Yan Wengui (active ca. 970–1030), the patriarch of "mountains and rivers without end." More than twice as long as any of Wang's earlier handscrolls, it is very likely that this scroll was intended to demonstrate his ability to assume responsibility for creating a pictorial document of the emperor's sojourn. An invitation to the capital in 1685 from the high-ranking Manchu Singde (1654–1685), who had accompanied the emperor on his first Southern Tour, may well have been intended as a preliminary step toward such a commission. But Singde died shortly before Wang's arrival, so he did not linger in the capital. Nonetheless, the trip led to his forging connections with several powerful court officials, who became major patrons and who were influential in his being selected several years later to create a grand pictorial record of the emperor's 1689 Southern Inspection Tour.\^/

Wang Hui's Copies the Old Masters and Works for the Emperor

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “All students of Chinese calligraphy and painting begin by making careful copies of earlier models. Wang Hui was no different, but his great facility in emulating earlier styles resulted in his being commissioned by collectors to produce a number of close copies of ancient masterpieces. Many of these copies bear Wang's signature and date, showing that he continued to create versions of old master paintings throughout his career. But Wang never made line-for-line replicas of his models. Instead, he enlivened his interpretations with his own vigorous brushwork, giving his copies a vibrant life of their own. It is for this reason that his copies were valued almost as highly as the originals. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Wang's expressive brushwork and kinesthetically charged compositions also reveal his authorship in unsigned evocations. In the eighteenth century, several of these "copies" entered the Qing imperial collection, where they were mistakenly catalogued as originals. Wang's Landscape after Fan Kuan's Travelers among Streams and Mountains was so enamored by the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–95) that he preferred it to the eleventh-century original.\^/

“The emergence of the Manchu regime as a patron of the arts developed slowly. Artistic production was hardly a priority in the first years of the Manchu Qing dynasty (1644–1911). The imperial workshops had been neglected since late Ming times, and, except for the anonymous artisans who maintained the decoration of the imperial palaces, there was no institutional entity that corresponded to a painting academy. Only in the last decade of the seventeenth century, when the Kangxi emperor commissioned a painting to document his 1689 Southern Inspection Tour, did the arts again rise to prominence in the imperial court.\^/

“In 1691, Wang Hui was summoned to Beijing to create a pictorial document of Kangxi's second Southern Tour. Dividing the emperor's journey into discrete episodes, Wang designed a series of twelve massive handscrolls, each measuring from forty to eighty feet in length (the entire set measures over 740 feet in length). Wang first made a set of full-scale drafts on paper, then enlisted a number of assistants to help with the finished version on silk, with specialists for the landscape, architecture, and the more than 30,000 figures. With the completion of this commission in 1698 (1979.5), the grandest artistic production of the age, the Qing court successfully identified itself with the highest scholarly traditions of Chinese art. “ \^/

Luo Ping, the Ghost Painter

Luo Ping was an 18th century Chinese artist who specialized in rendering ghosts. Yale historian and China expert Jonathan D. Spence wrote: “Luo Ping was not only innovative in “portraying” his ghosts with such specificity, he kept the element of surprise constantly to the fore...In the third section of his Ghost Amusement portrayed an absorbed amorous couple in unmarred human form, gazing into each other's eyes, while a man in the tall white hat of the underworld's guardians prepared to lead the couple into the netherworld. The woman's bared red shoes offered the viewer a signal that was, for the times, shockingly erotic. After four more panels of the magically displayed ghost figures, the eighth and final panel would have come with a startling force to the unprepared viewer---as two complete skeletons were portrayed standing tall and opposite each other in a clump of bare trees, dark rocks, and wild grasses. The precisely delineated specificity of these figures did not convey an auspicious message, but instead closed the scroll on a somber more than a mysterious note.”[Source: Jonathan D. Spence, New York Review of Books, in connection with Eccentric Visions: The Worlds of Luo Ping (1733-1799): an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, October 6, 2009; January 10, 2010]

Luo Ping ghost painting In one series of Luo Ping scrolls he art historian Yeewan Koon wrote: “Half naked with bald pates and small swollen stomachs, the two figures also recall the world of hungry ghosts, one of the Buddhist realms of existence. But the human emotions on the faces of Luo's ghosts place them in a gray consciousness that lurks between the real and the otherworldly. In this painting, Luo has created an ethereal existence by making his ghosts both strikingly familiar, through their human pathos, and evocatively strange,through their physical deformities.

Koon wrote: “The second leaf is a contrast of types: a skinny, bare-chested ghost with an official's hat follows a fat, bald ghost in tattered clothes against an empty background. The oscillation between specificity of types and ambiguity of situation allows room for a range of interpretations; some viewers were prompted to read this scene as phantasmagoric social commentary. [One scholar], for example, a Hanlin academician and playwright, described the figures in leaf 2 as a ‘slave ghost” and his master, whom he then compared to corrupt Confucian officials.

This “urge to rationalize the ghosts as allegories of human behavior,” adds Koon, “is derived in part from the theatrical immediacy of the images,” and in this sense the ghost paintings catch the tensions and contrasts that were coming to dominate this time in China's history---as well as the layers of religious euphoria that lay behind the alternate reading of the scrolls title as a “realm of ghosts,” a literalness of interpretation that Luo Ping deliberately fostered by his repeated claims that he had seen the ghosts in person on many occasions. This claim, writes Koon, was a part of Luo Ping's “invented persona as an artist who saw and painted ghosts,” a persona that ‘set him apart in a capital teeming with talent.”

See Separate Article CHINESE PAINTINGS OF GHOSTS AND GODS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Luo Ping ghost painting from the Met in New York, Nelson-Atking Museum, Ressel Fok collection, Shanghai Museum

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, U.S. government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2021