GHOSTS AND GODS IN CHINESE PAINTING

Luo Ping ghost painting According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““The concept of gods and ghosts formed with the rise of civilization, originating with the fears and uncertainties about the passing of life. From ancient China, the "Meaning of Sacrifices" chapter of The Book of Rites states, "Human life has both energy and spirit. Energy of the fullest measure is that of the gods. Living beings must die, and in dying must return to the earth; they are called 'ghosts.' [Or] the energy of a soul returns to the heavens; this is called a 'god.'" Thus, it was thought that when people die, they either ascended as virtuous "gods" or returned to the netherworld as evil "ghosts." Together, these two types of supernatural beings are known as "gods and ghosts" in Chinese. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The belief in gods and ghosts developed in the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties of high antiquity. By the following Qin and Han dynasties, under the influence of religious beliefs, the concept of cultivating spiritual paths to the gods and immortals gradually took root in the minds of people. Then in the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties period, political turbulence at the time and fragmentation of the country interrupted orderly dynastic succession, giving rise to an increased interest in spiritual and extraordinary aspects. Among the writings of this period, Biographies of Extraordinary Persons describes various strange matters and supernatural phenomena, combining elements of mythology, legend, and real life. Starting in the Tang dynasty, miscellaneous notes and novels containing tales of gods and demons appeared with greater frequency, such as Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang of the Tang dynasty, Extensive Records of Taiping from the Song dynasty, and Journey to the West and Investiture of the Gods from the Ming dynasty. Along with the rising popularity of stories surrounding the Eight Immortals, Hemp Maiden, and others, they came to form part of complex worlds comprising gods and immortals as well as ghosts and monsters.

“The painting of gods and ghosts has very early origins in China. In the Warring States period, Han Feizi had already pointed out that ghosts and goblins, being without form, are the easiest to paint. During the Qin and Han dynasties, images of riding on a dragon and ascending the heights became popular, and later in the Tang dynasty, Zhang Yanyuan's Record of Famous Paintings Through the Ages indicated that gods and ghosts had already become a subject in painting. Wu Daozi, for example, is recorded as having done "Illustrations of the Transformations in Hell" at Jingyun Temple in Chang'an, depicting various scenes of torture suffered by those who descended into hell. After completion, it is said that all who saw the painting trembled with fear. The depiction of the famous catcher of ghosts, Zhong Kui, also traces back to the Tang dynasty, and by the Five Dynasties period even more works of all sorts deal with beseeching auspiciousness and averting evil. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, such popular subjects serving as auspicious metaphors as the Eight Immortals and Three Star Gods (of Happiness, Prosperity, and Longevity) further enriched the depiction of gods and ghosts.

Popular subjects include the Eight Immortals, God of Longevity, Picking-Fungus Immortal, and Hemp Maiden. There are also gods, immortals, and goblins from literature such as the Goddess of the Luo River and Mountain Spirit as well as works about Zhong Kui and and his interaction with demons.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE PAINTING: THEMES, STYLES, AIMS AND IDEAS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; ART FROM CHINA'S GREAT DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTING FORMATS AND MATERIALS: INK, SEALS, HANDSCROLLS, ALBUM LEAVES AND FANS factsanddetails.com ; GREAT AND FAMOUS CHINESE PAINTINGS factsanddetails.com ; SUBJECTS OF CHINESE PAINTING: INSECTS, FISH, MOUNTAINS AND WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TAOIST ART: PAINTINGS OF GODS, IMMORTALS AND IMMORTALITY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTERS factsanddetails.com ; PAINTING FROM THE TANG, SONG, YUAN, MING AND QING DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; TANG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ART AND PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY ANIMAL, RELIGIOUS AND FIGURE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; YUAN ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; MING DYNASTY PAINTING AND ITS FOUR GREAT MASTERS factsanddetails.com ; QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Painting” by James Cahill (Rizzoli 1985) Amazon.com; “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” by Richard M. Barnhart, et al. (Yale University Press, 1997); Amazon.com; “How to Read Chinese Paintings” by Maxwell K. Hearn (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008) Amazon.com; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Taoist Gods

“Riding a Dragon” by Ma Yuan (fl. 1190-1224), Song dynasty, is a hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, measuring 108.1 x 52.6 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Ma Yuan, a native of Hezhong (modern Yongji in Shanxi), moved to Qiantang in Zhejiang. He served as a Painter-in-Attendance at the Painting Academy during the reigns of Guangzong and Ningzong in the Southern Song and excelled at landscape, figural, and bird-and-flower subjects. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Deities and immortals in Taoism are unrestricted by time or space, being free to roam at will by so-called "riding on the clouds and flying on a dragon, touring to and fro beyond the Four Seas." The billowing layers of clouds in this painting employ monochrome ink washes that seem to sparkle everywhere. Wind and clouds rise with a thunderclap as the immortal rides a dragon ascending on the gust, his wide sleeves and sashes billowing in the blast of air to suggest spiritual force, an attendant at his service. The brushwork features "trembling strokes" characteristic of Ma Yuan's style, being hoary and mature, its refinement having not diminished in the least despite the fading colors over the centuries.

“Three Officials Out on an Inspection” attributed to Ma Lin (fl. 1195-1264), Song dynasty, is a hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, measuring 174.2 x 122.9 centimeters. The "Three Officials" in Taoism refer to the Official of the Heavens bestowing blessings, the Official of the Land who pardons sins, and the Official of the Waters alleviating hardships. Together they are known as the Three Primes, with their rank being only lower than the Great Jade Emperor. The reason why they make an inspection tour is to observe good and evil in the land and take care of all living beings. The arrangement here is similar to that in a wall painting with the Three Officials divided into three levels and riding on the clouds or waters below. Each accompanied by a retinue, they are covered by a carriage or parasols for a very majestic effect. The followers include not only immortals of the heavens and waters but also demons of various forms, their interesting expressions quite lively and deserving closer examination.

“This work was originally attributed to Ma Lin, son of the court artist Ma Yuan (fl. 1190-1224). Ma Lin followed in the family style, becoming Attendant in the Painting Academy under Emperor Ningzong (r. 1195-1224). The style here, however, is different from his, the brushwork in the landscape forms being closer to that of a Ming dynasty (1368-1644) artist.

Paintings of Lohans

Lohans are sage-like beings whose profound enlightenment is somewhat similar bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism in East Asia. “Gathering of Lohans” is a painting by Ming artist Ding Yunpeng (1547-after 1628). According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Among precipitous cliffs in a forest of ancient trees is a gathering of lohans in various activities and poses, such as quietly sitting in meditation, reading from scriptures, and taming a dragon and tiger. The forms of many lohans are based on those of Guanxiu, emphasizing their foreign Indian background. Here, though, Ding Yunpeng has added a background of rocks and trees. By also having the figures interact with each other, Ding has created a lohan handscroll painting combined with such favored literati themes as a landscape and figures resting on rocks and trees. This work was done in relatively darker ink with coarse brushwork, the leaves varied but having a strong decorative effect. The signature at the end is dated to the equivalent of 1596, when Ding Yunpeng was 50 years old by Chinese reckoning. This being the earliest dated example of Ding's lohan painting in coarse brushwork, it is especially significant in understanding the development of his later style.

“The subject of sixteen lohans was a favorite religious theme depicted by Ding Yunpeng. In late spring of 1613, when Ding was 67 by Chinese reckoning, he did four paintings of lohans at a monk's dwelling on Tiger Hill in Suzhou, with each work depicting four lohans. Of the four lohans in one painting, one sits with eyes closed in meditation within a grotto, another concentrates chanting a sutra, one holds rosary beads, and another grasps a fly whisk as he teaches. The figures' heads are all large in proportion to their bodies, and their expressions appear exaggerated. The drapery lines are stiff and angular, the mountain and tree forms all rendered in dark ink. The brushwork is strong and hoary, the tree leaves outlined with fine lines, and the work strongly decorative. Overall, an awkward manner permeates the painting.

“Lohans” by the Ming Dynasty painter Wu Bin (ca. 1550-ca. 1621) is a hanging scroll, ink and colors on paper, measuring 151.1 x 80.7 centimeters. It shows lohans sitting on large rocks gazing at the unusual form of a dragon emerging from the clouds. The shapes of the rocks and clouds are quite extraordinary. At the top sits a figure wearing a red robe and holding a vase, probably referring to the lohan who had the power to make a spirit dragon appear. Records indicate that Wu Bin depicted 500 lohans for the Qixia Temple. After completing dozens of hanging scrolls, they later went into someone's collection and did not remain at the temple. Wu Bin's signature on this painting reads, "Bestowed at the Qixia Chan Temple as an offering." However, it also includes collection seals of Mi Wanzhong (ca. 1554-1631), suggesting it was one of the 500-lohan paintings that entered a private collection.

Goddess and Ghost Legends

Luo Ping ghost painting “Goddess of the Luo River” by Wei Jiuding (fl. ca. 14th century), Yuan dynasty, is a hanging scroll, ink on paper, measuring 90.8 x 31.8 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Wei Jiuding (style name Mingxuan), a native of Tiantai in Zhejiang, was an excellent painter of landscapes and figures, particularly specializing in ruled-line painting. An inscription here by Ni Zan (1301-1374) of the Yuan dynasty reads, "Inscribed on Wei Mingxuan's ‘Goddess of the Luo River.'" [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Legend has it that the Goddess of the Luo River was named Fufei, a daughter of the mythical ruler Fuxi. Falling and drowning in the Luo River, she became immortalized as the epitome of female beauty in "Ode to the Goddess of the Luo River" by the famous Wei poet Cao Zhi (192-232) of the Three Kingdoms period. The painter here used pliant yet strong and fluid lines of brushwork with pure and light ink tones to render the Goddess of the Luo River standing gently on clouds with the method of monochrome ink known as "baimiao." She hovers over the rippling surface of the river, the end of one of her robes fluttering gently in the breeze like a dragon twisting and ascending to the heavens. The elegance and grace here exhibits the spirited and extraordinary beauty of the Goddess of the Luo River.

“Strange Ghosts” by Pu Ru (1896-1963), Republican period, is an album leaf, ink and light colors on paper, measuring 22 x 14 centimeters. Pu Ru (also going by the name Xishan Yishi), better known his style name Xin-yu, was a member of the Manchu Qing imperial clan, being a grandson of Yixin, Prince Gong. In childhood he devoted himself to the study of literature, calligraphy, and painting, his style in the latter emerging from his studies for a pure and untrammeled manner out of the ordinary.

“This album consists of eight leaves, the artist using extremely simple brush strokes to render the different forms and supernatural appearance of ghosts and demons in the mountains and by the water. Though the works deal with ghosts, they do not seem to be very frightening. Rather, their lively appearances in the paintings with a pure and refreshing manner encourage closer appreciation. This work was entrusted to the National Palace Museum by the committee in charge of Pu Hsin-yu's Cold Jade Hall.

Zhong Kui: King of the Ghosts

“Zhong Kui Sending Off His Sister in Marriage” attributed to Wang Zhenpeng (fl. 1310-1335), Yuan dynasty, is a handscroll, ink on paper, measuring 27.5 x 298.2 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Legend has it that Zhong Kui was stripped of his honors in the civil service examinations due to his disfigured appearance and took his life on the palace steps. Fortunately, his friend Du Ping arranged for his burial. After Zhong Kui became the King of Ghosts, he sought to repay his friend's kindness and arranged to have his younger sister married to him, thus giving rise to the story of "Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Younger Sister." This work in "baimiao" monochrome ink lines depicts Zhong Kui wearing blossoms in his cap and riding a donkey as his legion of ghostly demons hold such auspicious objects as a musical instrument, lantern, plum blossoms, firecrackers, vase, halberd, and ball, making for a raucous scene as they send her off in marriage. The old title slip attributes this handscroll to Wang Zhenpeng, but features of the lines are different from the fine and delicate style associated with Wang's style, suggesting it is a later work with his name added. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Auspicious Omen of Abundant Peace” by an anonymous painter of an unspecified period is a hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, measuring 128.2 x 49.3 centimeters. This work depicts Zhong Kui wearing a red robe and holding a mirror in his left hand as he looks at his reflection. With a dark cap in his right hand, he sits on four demons as a heavenly bat soars above. Zhong Kui, with his disfigured looks, has by chance seen himself in the mirror. Startled by what he sees, his mouth is agape as he stares in surprise. The title of this work is also a homophone for "Ennobled Reflection of an Immortal." All depictions of Zhong Kui looking at himself in a mirror date to no earlier than the eighteenth century in the Qing dynasty, as seen Gao Qipei's "Zhong Kui in a Mirror" and Fang Xun's "Zhong Kui Facing a Mirror." Although the style of this work differs from these two, it presents an auspicious as well as humorous side to this figure, suggesting that it also came from the hand of a Qing dynasty artist.

“Zhong Kui Crossing a River” by Ding Yanyong (1902-1978), Republican period, is a hanging scroll, ink and colors on paper, measuring 69.8 x 46.3 centimeters. Ding Yanyong, a native of Maoming in Guangdong, in his early years studied Western oil painting at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, later returning to China and serving as a teacher at various art schools there. He went to Hong Kong in 1949. Ding experimented with new techniques in Chinese painting; though his style was influenced by that of Bada shanren, he had a personal manner of his own. This painting depicts Zhong Kui wearing a straw hat and a wide robe with a round collar, his beard flying in the wind. With eyes wide open, he stands on a small skiff holding a sword in one hand and a small ghost in the other. His form is exaggerated but imposing and compelling. The composition is succinct, the brushwork rounded and forceful, and the coloring bright and bold, all representing a departure from tradition.

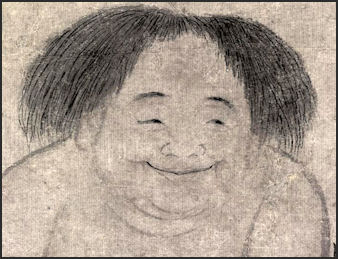

Luo Ping, the Ghost Painter

Luo Ping ghost painting Luo Ping was an 18th century Chinese artist who specialized in rendering ghosts. Yale historian and China expert Jonathan D. Spence wrote: “Luo Ping was not only innovative in “portraying” his ghosts with such specificity, he kept the element of surprise constantly to the fore...In the third section of his Ghost Amusement portrayed an absorbed amorous couple in unmarred human form, gazing into each other's eyes, while a man in the tall white hat of the underworld's guardians prepared to lead the couple into the netherworld. The woman's bared red shoes offered the viewer a signal that was, for the times, shockingly erotic. After four more panels of the magically displayed ghost figures, the eighth and final panel would have come with a startling force to the unprepared viewer---as two complete skeletons were portrayed standing tall and opposite each other in a clump of bare trees, dark rocks, and wild grasses. The precisely delineated specificity of these figures did not convey an auspicious message, but instead closed the scroll on a somber more than a mysterious note.”[Source: Jonathan D. Spence, New York Review of Books, in connection with Eccentric Visions: The Worlds of Luo Ping (1733-1799): an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, October 6, 2009; January 10, 2010]

In one series of Luo Ping scrolls he art historian Yeewan Koon wrote: “Half naked with bald pates and small swollen stomachs, the two figures also recall the world of hungry ghosts, one of the Buddhist realms of existence. But the human emotions on the faces of Luo's ghosts place them in a gray consciousness that lurks between the real and the otherworldly. In this painting, Luo has created an ethereal existence by making his ghosts both strikingly familiar, through their human pathos, and evocatively strange,through their physical deformities.

Koon wrote: “The second leaf is a contrast of types: a skinny, bare-chested ghost with an official's hat follows a fat, bald ghost in tattered clothes against an empty background. The oscillation between specificity of types and ambiguity of situation allows room for a range of interpretations; some viewers were prompted to read this scene as phantasmagoric social commentary. [One scholar], for example, a Hanlin academician and playwright, described the figures in leaf 2 as a ‘slave ghost” and his master, whom he then compared to corrupt Confucian officials.

This “urge to rationalize the ghosts as allegories of human behavior,” adds Koon, “is derived in part from the theatrical immediacy of the images,” and in this sense the ghost paintings catch the tensions and contrasts that were coming to dominate this time in China's history---as well as the layers of religious euphoria that lay behind the alternate reading of the scrolls title as a “realm of ghosts,” a literalness of interpretation that Luo Ping deliberately fostered by his repeated claims that he had seen the ghosts in person on many occasions. This claim, writes Koon, was a part of Luo Ping's “invented persona as an artist who saw and painted ghosts,” a persona that ‘set him apart in a capital teeming with talent.”

Life of Luo Ping

Spence wrote: “Luo Ping, who lived from 1733 to 1799, was perfectly placed by time and circumstance to view the shifts in fortune that were so prominent in China at that period. He grew up in Yangzhou, a prosperous city on the Grand Canal, just north of the Yangzi River, which linked the capital at Beijing with the prosperous commercial and intellectual hubs of Suzhou and Hangzhou. Yangzhou's strategic location and commercial prominence served it well, and by the time of Luo Ping's birth it” was---the financial center for the salt merchants of coastal and central China, who purchased from the central government the right to sell and transplant salt, and built up colossal private fortunes from this lucrative trade.” [Source: Jonathan D. Spence, New York Review of Books]

“Partly because of the lavish kickbacks that the merchants made to local officials and to the emperor's personal household managers, the city was graced with six visits from Emperor Qianlong, visits that sparked a building boom in order to provide adequately opulent living quarters for the imperial visitor and his entourage. At the same time there were correspondingly lavish expansions of Buddhist temples, decorative waterways, elaborate gardens, and a predictably energized ambience of restaurants, teahouses, and brothels.”

“The city was favored with both imperial patronage and the generosity of the salt merchants---many of whom assembled magnificent libraries and hired renowned local scholars as cultural amanuenses or tutors to their children, so that they might have a chance to pass the imperial examinations. This vibrant intellectual world in its turn attracted other scholars and artists to the region so that Yangzhou became a byword for informed connoisseurship and aesthetic exploration.”

“Luo Ping's father had passed the second level of the state examinations, which was no small feat, and could be achieved only by those with excellent academic training---but he died before Luo Ping was one year old; the most celebrated ancestor Luo could claim was a great-grandmother who was glorified---at least in family lore and reminiscence---for having taken her own life in the fierce siege of 1645. Luo was raised by an uncle, who saw that he got a good education, fostered his skills as a poet, and introduced him to some of the wealthy merchants known for their cultural gatherings. At age nineteen, Luo married a finely educated woman, already celebrated for her literary and artistic skills, with whom he had three children, who also became accomplished poets and painters.”

Luo Ping and His Patron

Luo Ping ghost painting Spence wrote: “Around 1757 Luo Ping met and became friends with a seventy-year-old widower, Jin Nong, who was living alone in one of the many Buddhist temples in the city. In his prime, Jin had worked variously as an art dealer, calligrapher, and tutor, and had built up a national reputation as a poet and a painter. One of his many specialties was painting plum blossoms, a genre at which Luo and his wife were also skilled. Jin's eyesight was fading, and it was apparently a natural step for the two men to become friends.”[Source: Jonathan D. Spence, New York Review of Books]

“Jin was often behind with a backlog of orders for painted scrolls and calligraphy, and for Buddhist devotional art (another of his specialties). It was in tune with the spirit of the times to take on more than one could accomplish, and it was natural for Jin to turn to Luo Ping for help, as he did to various other young students or assistants. One unanticipated consequence was that Jin was more than just a teacher and mentor to Luo---he became a friend of the family, and often visited Luo and his wife, staying sometimes at their residence in Yangzhou for days or even weeks. Some Yangzhou artists and scholars chided Jin Nong for exploiting his young assistants as ‘substitute brushes” or “ghost painters,” saying that the practice showed his “laziness” and indicated that he was “taking advantage of his pupils for the sake of profits.”

By chance, one of Jin Nong's letters to Luo Ping has survived, giving quite precise details about what the older man was seeking from his ghost painter: “Paint a vermilion bamboo with bright pigment. To be excellent, it must be luxurious and fresh with an antique flavor. Leave more empty space so that I can easily inscribe it. Paint another one: an ink bamboo using the other one as a model, but don't do anything too surprising. For the ink bamboo, half a teacup of ink should be enough.”

“In another letter we see Jin Nong giving even tighter guidelines. The ghost painter must leave adequate space next to the two Buddhist figures, writes Jin, for “if the inscription is too small, it will be unsatisfactory.” “Tomorrow morning I will send paper for the ink bamboo,” adds Jin, “along with some prepared ink.” In the closing lines of this letter he writes, “If you will again paint for me, I will choose some excellent objects to present in exchange,” and he closes quietly, “Letter written by lamplight on the 27th.”

Luo Ping Achieves Fame as Ghost Painter

“By the early 1780s,” Spence wrote, “We can find nationally known Chinese scholars singling out three of Luo Ping's paintings for special praise” including a “work identified as Ghost Amusement. This alerts us to the other side of Luo Ping's labors as a ghost painter, namely that of being a painter of ghosts, for it was as a painter of ghostly images that Luo achieved his final leap into the ranks of upper-literati society. This quest led him...to Beijing, where prestigious officials were gathered in the greatest numbers and the chances for preferment beckoned. He carried the Ghost Amusement scroll with him. “This was a bold and perhaps almost unprecedented experiment, which carried within it a way of confronting the dangers of the unknown and probing the meanings of the underworld through his own vision of the ghost worlds that for most of us are never revealed or comprehended. The painting may have been originally conceived as a series of individual leaves, and the first identifiable colophon---or attached brief statement---from an influential scholar to whom Luo showed the initial ghost images can be dated to 1766. But in Beijing, as Luo learned to make his way and expand his contacts, success followed fast: nine new colophons were added to his scroll in 1772, four more in 1773, one in 1774, a steady scattering in the later 1770s and 1780s, and a further torrent in Luo's final years, with six in 1790 and seven in 1791]

From 1790 onward Luo lived mainly in Beijing, often with his two sons, who seem to have been successful painters. He remained busy and active into the 1790s and, among numerous commissions and social events, found time in 1797 to create a second version of his Ghost Amusement scroll, similar in main outline to the original version from the 1760s but with a different---though still Western---version of a skeleton in the final panel...Luo Ping died in 1799, but the tokens of respect for his ghost images continued in written form throughout the nineteenth century.” Sometime after his death, an art connoisseur wrote on the same portrait scroll in an undated colophon that Luo had been a “completely original painter of Buddhist figures, Daoist immortals, and ghosts,” and added that Luo had been “a man of exceptional creativity” who was “never muddled” and “painted with a limpid lucidity.” The colophon writer added that “before reaching old age [Luo] withered away and died.”

Image Sources: Luo Ping ghost painting from the Met in New York, Nelson-Atking Museum, Ressel Fok collection, Shanghai Museum.

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021