HAN DYNASTY ART

ceramic dancers found in tombs

Objects unearthed from Han-era ( 206 B.C. to A.D. 220) tombs include gilded silkworms; stones with humans battling bears; golden belt buckles with a bear and a tiger devouring a horse; bronze incense burners held by an image of an immortal; horned terra cotta heads used to ward off evil; and pear ornaments with girls holding lamps that would show the way to the afterlife. [Source: Mike Edwards, National Geographic, February 2004]

Our knowledge of the arts is drawn from two sources—literature, and the actual discoveries in the excavations. Thus we know that most of the painting was done on silk, of which plenty came into the market through the control of silk-producing southern China. Paper had meanwhile been invented in the second century B.C., by perfecting the techniques of making bark-cloth and felt. Unfortunately nothing remains of the actual works that were the first examples of what the Chinese everywhere were beginning to call "art". [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Many great works of pottery and ceramic art came from the Han Dynasty. Lovely vessels and objects were buried with the dead and have been excavated by archeologists and looters. The first use of glazes on Chinese pottery dates back to this period. Han emperors and noblemen commonly decorated their tombs with pottery replicas of warriors, concubines, servants, horses, domestic animals, trees, plants, furniture, models of towers, granaries, mortars and pestles, stoves and toilets, and almost everything found in the real world so the deceased would have everything he needed in the next world.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Works include bronze mirrors and seals, “jades, lacquerware, ceramics, bronzes, textiles, paintings, wooden slips, wall art, stone carvings and sculpture, and bricks and tiles. In terms of jades, the most representative items here include; a pi disc, a set of jade pieces, a jade-decorated sword, a cup, a cicada amulet, a pig-shaped carving, and a jade suit sewn together with gold, silver, and copper. Lacquerware was popular in the everyday life of the upperclass. The most common forms here include a wine container, a food vessel, a case, a winged-cup, and plates and basins. Ceramics include a celadon bowl and container as well as items in yellow and green glaze, a pot, a miniature tower and animals, and figures. Tiles and "pictorial" bricks, although materials associated with architecture and tombs (respectively), also reveal the beauty of visual art and design in the Han dynasty. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/ ]

Famous Han era pieces at the National Palace Museum, Taipei, include: a jade horn-shaped drinking cup with dragon design; a pottery hu in the shape of a cocoon; a bronze chia-liang standard measure; a bronze mirror with figure motif; and a jade his-pi small disk with dragon design.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ZHOU, QIN AND HAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; HAN DYNASTY (206 B.C.-A.D. 220) factsanddetails.com; LIU BANG AND THE CIVIL WAR THAT BROUGHT THE HAN TO POWER factsanddetails.com; HAN DYNASTY RULERS factsanddetails.com; EMPEROR WU DI factsanddetails.com; WANG MANG: EMPEROR OF THE BRIEF XIN DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; RELIGION AND IDEOLOGY DURING THE HAN DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; CHINESE CERAMICS factsanddetails.com ; PORCELAIN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CELADONS factsanddetails.com ; JIANGDEZHEN AND ITS PORCELAIN, KILNS AND GLAZING AND PAINTING TECNIQUES factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: Han Dynasty Wikipedia ; Early Chinese History: 1) Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; 2) Chinese Text Project ctext.org ; 3) Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Age of Empires: Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties” by Zhixin Sun, I-tien Hsing Amazon.com; “Tomb Treasures: New Discoveries from China's Han Dynasty” by Jay Xu Amazon.com; “Daily Life in Ancient China” by Mu-chou Poo Amazon.com; “Life in Ancient China” by Paul Challen Amazon.com ; “Early Chinese Religion” edited by John Lagerwey & Marc Kalinowski (Leiden: 2009) Amazon.com; “The Organization of Imperial Workshops during the Han Dynasty” by Dr. Anthony Jerome Barbieri-Low Amazon.com; "The Cambridge Illustrated History of China" by Patricia Buckley Ebre Amazon.com; Bronzes: “Chinese Bronzes” by Christian Deydier Amazon.com; “Chinese Bronze Ware” by Li Song Amazon.com; “A Source Book of Ancient Chinese Bronze Inscriptions” by Constance A Cook (Editor), R Goldin Paul (Editor) Amazon.com ; Art: “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Artists and the Subjects of Art in the Han Dynasty

Han-era jade tiger Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: "People", that is to say the gentry, painted as a social pastime, just as they assembled together for poetry, discussion, or performances of song and dance; they painted as an aesthetic pleasure and rarely as a means of earning. We find philosophic ideas or greetings, emotions, and experiences represented by paintings—paintings with fanciful or ideal landscapes; paintings representing life and environment of the cultured class in idealized form, never naturalistic either in fact or in intention. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Until recently it was an indispensable condition in the Chinese view that an artist must be "cultured" and be a member of the gentry—distinguished, unoccupied, wealthy. A man who was paid for his work, for instance for a portrait for the ancestral cult, was until late time regarded as a craftsman, not as an artist. Yet, these "craftsmen" have produced in Han time and even earlier, many works which, in our view, undoubtedly belong to the realm of art. In the tombs have been found reliefs whose technique is generally intermediate between simple outline engraving and intaglio. The lining-in is most frequently executed in scratched lines. The representations, mostly in strips placed one above another, are of lively historical scenes, scenes from the life of the dead, great ritual ceremonies, or adventurous scenes from mythology. Bronze vessels have representations in inlaid gold and silver, mostly of animals.

The most important documents of the painting of the Han period have also been found in tombs. We see especially ladies and gentlemen of society, with richly ornamented, elegant, expensive clothing that is very reminiscent of the clothing customary to this day in Japan. There are also artistic representations of human figures on lacquer caskets. While sculpture was not strongly developed, the architecture of the Han must have been magnificent and technically highly complex.

History, Culture and Religion Behind Han Dynasty Art

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “The Chinese imperial period began with the unification of China in 221 B.C. by the state of Qin and the consolidation of a huge empire under the succeeding Han dynasty (206 B.C. - AD 220). Consolidating the empire involved not merely geographical expansion, but also bringing together and reconciling the ideas and practices that had developed in the different states. The new state incorporated elements of Legalism, Daoism, and Confucianism in its ideology but the officials who administered the state came to be identified more and more with Confucian learning. Reflecting the development of religious practices during the Warring States period, Han art and literature are rich in references to spirits, portents, myths, the strange, and the powerful. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “During the Han Dynasty Chinese civilization underwent enormous change. Politically, there was the end of feudalism and the emergence of the fountainhead of the imperial system. Socially, the strict hierarchy was crumbling in the face of increasing egalitarianism. Ideologically, studies especially catering to the nobility broadened to a wider, richer pool of knowledge to which all scholars could contribute. Finally, the Confucian school of thought ultimately prevailed and was endorsed by the government. Culturally, the era still placed focus on the practice of rites and ceremonies for the spirits, but it also represents the last gasp in the use of bronze ritual objects as cultural symbols. Replacing them were various objects of daily life that highlighted the utilitarian, pluralistic, and lively aspects of the people. From a broader perspective, such "traditions" that persisted and survived to impact the ensuing development of Chinese civilization actually originated in the Ch'in (221-207 B.C.) and Han (206 B.C.-220 C.E.) period. Indeed, it was truly a pivotal time of transition from the "classic" to "tradition". [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/ ]

Han bronze “During the Qin and Han, bronze and jade objects were still considered valuables reserved for the upper echelons of society. The sword, knife, seal, and jade ornaments, as well as a bronze mirror, were what a gentleman would carry on him. Everyday objects used by people of different classes include “vessels for cooking food, such as "ting", "tseng", and "yen"; containers for drinks, such as "tsun", "ho", "hu" and cups; water vessels, such as "chien" and "p'an"; lamps for providing light; "po-shan" censers for making the air fragrant; and sheep-shaped weights for holding things down. \=/

“From the numerous traditions that developed during the previous Spring and Autumn as well as Warring States periods, people in the Ch'in and Han dynasties adopted a more regulated and eternal view of the cosmos, one which revealed itself in concrete terms through many of the decorative motifs used at the time. The popularity of such subjects as the phoenix and dragon as well as the Four Spirits reinforces the belief in the Yin-yang and Five Elements. The prevalence of cloud patterns, astrological images, mountains of the immortals, auspicious beasts, winged figures, and the Queen Mother of the West also demonstrates this worldview of cosmic order as well as life and death. In addition to expressing these views of a more abstract nature, Han dynasty spiritual life also dealt with more immediate and earthly desires, as reflected in such auspicious inscriptions as "Everlasting happiness", "Life without bounds", "Great luck all around", and "Filial descendants".” Sculpture and temple architecture and cave painting received a great stimulus with the spread of Buddhism in China.\=/

Examples of Art from the Han Dynasty

The three-footed, Han-Dynasty inkstone with lid of auspicious animal decor is 23.2 centimeters tall. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “This is a typical inkstone from the late Eastern Han (A.D. 25-220). It is comprised of the base and a cover, which is carved in high relief in the form of an auspicious animal standing proudly with an open mouth. The sides are carved in the form of two openwork dragons. The round cover is concave inside and fits over the raised lip of the inkstone. The surface is flat and the ridge would have held the ink inside. The legs are represented in the form of bears carved in relief with a band of six dragons connecting them. Both parts of the inkstone are carved with great detail. The characters "Chun i kuan" are engraved under the chin of the auspicious animal. Thus, this is not only a rare surviving example of this inkstone type, but it also of exceptional quality. \=/

Rubbing of detail of a hunting scene from lintel relief is 11.2 centimeters tall, 19.9 centimeters long and 8.8 centimeters wide. “In Han architecture, lintels were used to distribute the weight of a structure down to the posts. This type of repetitive post and lintel system was often used to build underground tomb vaults. The individual members were pressed from clay to create the appropriate shape, decorated, and then fired to harden them. Rubbings in ink on paper placed over these pottery members with designs can be done to make it what looks like drawings, which is why they are often called "pictorial bricks." Many decorated tomb gates, walls, and ceilings have been found from the Han dynasty. This particular hunting scene is from an illustrated brick that once formed a lintel in a tomb. The delicate yet taut lines capture the pose of the tiger and the energy of the hunters. This tense and lively composition is complemented by the delicate and flowing forms and lines to give an almost cartoon-like effect. \=/

Painting and Calligraphy in the Han Period

painting on a tomb brick

Pictorial art during the Han Dynasty took the from of stone engraving, wall painting, and paintings on silk. Paintings mentioned in the Han period texts include Picture of Riding the Dragon to Ascend the Clouds, Picture of the Eastern Wall and Picture of the Western Wall, and Scripture of Grand Harmony. None of these remain today and we have no clue what they looked like. Han painting is thought to have had a solemn style and didactic function. The main objective of painting during this period was to educate people.

After the invention of paper, calligraphy became an important art form to the Chinese. Chinese scribes used brush and ink to create beautiful characters with one or more strokes. Paper was the perfect medium for calligraphy since it absorbed the ink well. Before paper, the Chinese wrote on silk which could be rolled easily, but which was also very expensive. Bamboo strips were also used, but they were very bulky. Paper was both cheaper and easier to bind together into books. It was made out of silk, hemp, bamboo, and seaweed pulp that was dried on a screen. [Source: Ancient China, Jennifer Barborek, Boston University]

Ceramics in the Han Dynasty

Some experts believe the first true porcelain was made in Zhejiang province during the Eastern Han dynasty. Shards recovered from archaeological Eastern Han kiln sites estimated firing temperature ranged from 1,260 to 1,300 ̊C (2,300 to 2,370 ̊F). As far back as 1000 BC, the so-called "porcelaneous wares" or "proto-porcelain wares" were made using at least some kaolin fired at high temperatures. The dividing line between the two and true porcelain wares is not a clear one. Archaeological finds have pushed the dates to as early as the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). The late Han years saw the early development of the peculiar art form of hunping, or "soul jar": a funerary jar whose top was decorated by a sculptural composition. This type vessels became widespread during the following Jin dynasty (265–420) and the Six Dynasties. [Source: Wikipedia]

Glazed pottery and lacquerware were also seldom used by ordinary people. Gray pottery is what appeared among the belongings of the vast number of people in society, either for use in daily life or as funerary accompaniment. In Han dynasty funerals, large numbers of pottery figures were often made to accompany the tomb occupant. Made from clay fired at low temperatures, this type of pottery is relatively soft. Surfaces were covered with a fine layer of white clay and then painted with pigments of various colors to describe the details. In general, Han sculptural art did not strive for outward precision and realism, but artisans often paid special attention to emotions and energy, including the spirit. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/

Grey pottery horse and rider painted in unfired colors from the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 8) is 50 centimeters tall and 44 centimeters wide. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “This work is actually composed of three pieces; the rider, the horse, and its tail. The rider is shown wearing a cap that is draped over his head, leaving the face bare. The facial features have been lightly touched, revealing a gentle yet firm expression. He wears a suit covered with plates to indicate armor, suggesting that he is a calvary soldier. Sitting astride the horse, his hands are held up in a position of holding reins. The muscular horse stands rigid with its head held up, ears straight, and tail poised ready for action. With its mouth open, the energy and spirit of this magnificent animal have been remarkably portrayed. The body of the horse has also been painted to depict the saddle and accessories, adding details and color to the work. \=/

Han Dynasty Bronze

Bronze horsePatricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “By the Western Han period, iron had become the material of choice for agricultural tools and weapons, and the number of bronze objects in tombs decreases dramatically. Those objects that were made of bronze were primarily coins and mirrors rather than vessels. The bronze vessel as an art form also declined with the rise of representational art in the Han period. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The majority of the most desirable bronze wares during Han dynasty were of new genres, including Boshan mountain-shaped incense burners, barrel-shaped zun for wine, hou-lou vessels for soup, and various styles of lamps and lanterns for lighting, all catering to personal enjoyment of a fine, worldly life. As to ornamentation, the new patterns or designs were either simple or lively, or sometimes teeming with romantic imagination toward immortal worlds. The contents of inscriptions carried more auspicious expressions in addition to being just practical records.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Bronze vessels did not reach the quality of casting found in the previous Shang and Zhou dynasties, when the art of bronze dominated the production of vessels for rituals and ceremonies and the techniques for making them less refined. However, in terms of gilt bronzes, Han craftsmen produced a rich variety of shapes and styles that opened another facet on this art form. In addition to the production of wine vessels, mirrors, and weapons, we also find the technique of gilded bronze on, for example, a lamp, horse, po-shan incense burner, and belt hook. Seals made of bronze were reserved for the use of the emperor and major officials. The simple and steady manner of seal carving in the Han dynasty became a standard followed by later generations. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

The unification under one imperial rule that occurred during the Qin and Han Dynasties brought together from different styles from the four corners of the empire The spread of local bronzes to the Central Plains also helped facilitate the integration process of Chinese Culture. The process also worked in reverse. Under the universal rule of the empires, a new, exciting, and magnificent era arrived with full momentum. Though the changeover of the post-bronze age did not take place overnight but the ramifications impacted future Chinese. The colorful multicultural presence existed from late Shang, through Western Zhou, and then into Eastern Zhou, creating a dazzling array of various bronze civilizations, each with its distinctive characteristics. These cultures scattered around in the north (today's Hebei, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Northeast), in Ba & Shu (today's Sichuan), in Dian (today's Yunan), and today's Hunan, Guangdong, and Guangxi. Their bronzes were either influenced by the Central Plains as a result of interactions, or purely exhibiting local arts and variations of their owns.

See Separate Article BRONZE ART IN ANCIENT CHINA: RITUAL VESSELS AND HOW THEY WERE CAST factsanddetails.com

Han Dynasty Bronze Objects

Perhaps the greatest testimony of Han dynasty artistic achievement and skill was the "Flying horse," an A.D. second century bronze sculpture of an entire horse supported on the hoof of one leg found in the grave of a Han general. A famous gilded bronze horse is another treasure. It is thought to have been given as a gift from Emperor Wu Di to his sister. Horses were valued for practical and spiritual reason. They carried the Han to Central Asia and were believed to carry the emperor to heaven. [Source: Mike Edwards, National Geographic, February 2004]

Han bronze pieces at the National Palace Museum, Taipei include 1) Mirror of Shang-fang with TLV pattern Han Dynasty, Han Dynasty, c. 3rd century B.C. to A,D, 3rd century, height: 16.6 centimeters; 2) Jia-liang Fine standard measure, A.D. Xin Dynasty 9-24, height: 25.6 centimeters width: 34 centimeters. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Tomb of Liu Sheng Xin Dynasty bronze, dated to A.D. 9, is 25 centimeters tall. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ When Wang Mang usurped the throne from the Han, he changed the name of the dynasty to Hsin. In order to unify the standards of measure under his rule, in 9 AD (the first year of his reign), he ordered that they be established and cast. The purpose was to create objects for making measurements that could be used throughout the entire country. Here, we find such an example cast in bronze, indicating the importance of this dynastic standard. The 216 characters on the surface also explain its origins, the individual parts of the object, and the dimensions. The object itself can be divided into five measuring parts. The central container is the main one, with it and the others all engraved with corresponding unit names. To combine as many measurements in one object, it could also be turned upside down, depending on which measurement was being made. Study of this object shows that measurements were made in units of ten, presenting us with a way to understand ancient methods of calculation. For example, judging from the object and the inscription, we find that one "foot" in the Hsin dynasty equaled 23.0887 centimeters. Based on this, other measurements can also be made. Thus, this standard offers us a glimpse at the measures used at the time. \=/

An Eastern Han Dynasty (A.D. 25-220) gilt bronze tsun wine vessel with mountain scenes and animal feet is 19.6 centimeters) tall. “ This gilt bronze tsun vessel is simple in shape, consisting of a domed cover, vertical sides, and three legs in the form of animals. The cover and body, however, are decorated with lively mountain scenes in relief. Among the mountains are spirits, birds, and other animals, representing contemporary attitudes towards the forests and mountains and revealing the lively Han view of spirit and form in Nature. Due to the age and uneven surface of this piece, much of the gilding flaked off, showing just how difficult this gilding process was. The origins of Chinese landscape art probably began in the carved stone images of the Han dynasty. This bronze shows rows of mountains inhabited with animals, serving not only as decoration, but also as an ideal representation of the land. Thus, this important work stands at the beginning of landscape art in China. \=/

Bronze Mirrors of the Han Dynasty

Aileen Kawagoe wrote in Heritage of Japan: During the Han and Tang Dynasties, “Chinese mirrors were symbols of rulership or kingship, diplomatic gifts from China and status items exchanged with the sealing of political alliances. They were often traded, exchanged as diplomatic and political gifts, kept as grave goods in tombs and passed on as clan heirlooms. Different features and designs developed in different periods, with the various symbols and inscriptions on the back of the mirror indicative of the politics, economy, ideology, culture and social custom of the age. Bronze mirrors were typically round, polished brightly on one side, with designs on the back. Han and Tang mirrors were the most sophisticated. Later Han mirrors inherited this moral storytelling tradition with mirrors’ pictorial motifs bearing the narrative elements of the Story of Wu Zixu. (The Han people were especially fond of rhetoric, dialogue and storytelling and their mirrors reflect this.) [Source:Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website]

The TLV bronze mirror was a bronze mirror that was popular during the Han Dynasty in China. It was so called because called TLV mirrors because the engraved symbols resemble the letters T, L, and V. Produced from around the 2nd century B.C. until the 2nd century AD, the dragon was an important symbol of these early TLV mirrors. The "Xianren bulao" TLV Bronze Mirror at the National Palace Museum, Taipei was made during Xin to early Eastern Han period, A.D. 1st century and is 20.3 centimeters in diameter. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““This round mirror has a hemispherical knob on a quatrefoil base in the form of a persimmon calyx and within a square double-outline square. The interior of the square is ringed with an inscription of twelve characters for the Earthly Branches. The area outside is decorated with a TLV pattern and interspersed with eight nipples and the Four Spirit Animals (Green Dragon, White Tiger, Red Bird, and Black Tortoise) as well as other flying birds and auspicious beasts in a complex array. An outer ring features an inscription describing the realm of the immortals, and the mirror rim is ringed by a sawtooth pattern with an outer circle of cloud patterns. The appearance of the TLV pattern, Four Spirit Animals, characters for the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches, and inscriptions dealing with the immortals reflects apocryphal thought popular in the late Western Han to Xin period. The Qianlong emperor in the Qing dynasty ranked this mirror in the "first top grade." [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

According to Schuyler Camman the designs on TLV mirrors were symbols of the heavens or the cosmological world the Chinese believed in. 1) The V shapes framed the inner square, and that the central square is thought to represent China as the ‘Middle Kingdom, as well as the ancient Chinese idea that heaven was round and earth was square. This illustrated the Chinese idea of the five directions — North, South, West, East and Center. ’ The area in between the central square and the circle represented the ‘Four Seas.’ During the Han Dynasty the ‘Four Seas’ represented territories outside China. The nine nipples in the central square likely represented the ‘nine regions of the earth as discussed by Cammann as having come from the Shiji. 2) The Ts reflected the ‘Four Gates of the Middle Kingdom’ idea present in Chinese literature, or possibly the four inner gates of the Han place of sacrifice, or the gates of the imperial tombs built during the Han period. 3) The Ls are thought to have symbolized the marshes and swamps beyond the ‘Four Seas,’ at the ends of the earth. The Ls seem to bend possibly to achieve a rotating effect which symbolized the four seasons, or the cardinal directions. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website]

Treasures from the Han Tomb of Liu Sheng

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ In 1968 two tombs were found in present-day Mancheng County in Hebei province (review map). The first undisturbed royal Western Han tombs ever discovered, they belong to the prince Liu Sheng (d. 113 B.C.), who was a son of Emperor Jing Di, and Liu Sheng's consort Dou Wan. The structure and layout of the tombs departs from earlier traditions in significant ways. For the first time images of daily life began to appear in tombs in the form of wall reliefs and earthenware models. Before this time, representations of scenes from life had been rare, a minor artistic concern when compared to the interest in shapes and surface decoration. In the tombs at Mancheng, however, the bronzes are mostly unadorned vessels meant for everyday use. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Liu Sheng's tomb contained over 2,700 burial objects. Among them, bronze and iron items predominate. Altogether there were: A) 419 bronze objects; B) 499 iron objects; C) 21 gold items; D) 77 silver items; E) 78 jade objects; F) 70 lacquer objects; G) 6 chariots (in south side-chamber); H) 571 pieces of pottery (mainly in north side-chamber); I) silk fabric; J) gold and silver acupuncture needles (length: 6-7 centimeters); J) an iron dagger (length: 36.4 centimeters width: 6.4 centimeters); K) three bronze leopards inlaid with gold and silver plum-blossom designs; L) bronze weights (height: 3.5 centimeters, length: 5.8 centimeters; M) a bronze ding with two ears fitted with movable animal-shaped pegs to keep the cover tight; N) a double cup with a bird-like creature in the center that holds a jade ring in its mouth and its feet are planted on another animal. /=\

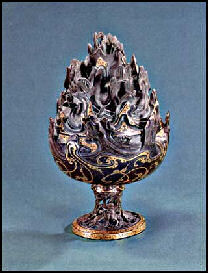

There was also a bronze incense burner inlaid with gold (height: 26 centimeters). According to Ebrey: “Three dragons emerge from the openwork foot to support the bowl of the burner. The bowl is decorated with a pattern of swirling gold inlay suggestive of waves. The lid of the burner is formed of flame-shaped peaks, among which are trees, animals, and immortals. There are many tiny holes in the peaks. Oil-burning lamps were a common means of night-time illumination in this and later periods. A bronze lamp (height: 48 centimeters) has an ingenious movable door to regulate the supply of oxygen and thus the strength of the fire. Smoke from the fire would go up the sleeve, keeping the room from getting too smoky.” /=\

jade burial suit

Jade During the Han Dynasties

During the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. - 220 A.D.), the imperial family held jade in great esteem. While alive they wore jade pendants and ingested jade powder. When they died they were covered and stuffed with jade. Banners and tomb tiles were imprinted the round pi disk, which was believed to assist the deceased reach the next world quicker.

In the Han period, when jade objects were believed to possess auspicious meaning, their uses and functions multiplied. Circular jades — often containing images of twin-bodied animals, mask patterns, grain seeds, rush mat designs, curling chih dragons, and round tipped nipples — decorated buildings. Engraved dragon and phoenix patterns were popular in the Han imperial court.

A Han Dynasty Pi disc with carved chih dragon and ch'ang-le characters is a beautiful piece. According to he National Palace Museum, Taipei: “This greenish jade disc is mottled brown in places and semi-translucent. This exceptional jade was ground and carved using three techniques; openwork, engraving, and low-relief carving. It can also be divided into three parts; a central disc (with a hole in the middle) decorated with raised dots, an openwork rim around the disc (decorated with phoenixes and dragons), and an openwork decoration at the top above the border. This type of design extending beyond the border is known as a "beyond-the-rim pi disc." In the openwork border at the top and bottom are the characters for "ch'ang" (everlasting) and "le" (happiness). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/]

“Although often cited by scholars in describing this type of decoration and related to other archaeologically excavated examples, this disc (technically speaking) does not bear "beyond-the-rim" decoration, because the additional openwork merely appears appended to the border. As a result, no decoration extends from the center to the outside in a connected fashion. Artifacts in other museums are perhaps better examples of this type. However, the lively interaction of phoenixes and dragons in the openwork rim of this ch'ang-le disc seem to extend at least in spirit and energy. Furthermore, this type of design goes far beyond traditional ones, making this not only a rare specimen in the history of jades, but also a representative example of the new heights in the art of jade at the time. \=/

Liu Xu jade suit replica

Han Dynasty Jade Suits

The greatest expressions of the quest for immortality were the jade suits that appeared around the 2nd century B.C. About 40 of these jade suits have been unearthed. The jade suit of the 2nd century B.C. Prince Liu Sheng unearthed near Chengdu, Sichuan province was made of 2,498 jade plates sewn together with silk and gold wire. Liu Shen was buried with his consort who was equally well clad in a jade suit. Sufficient room was made for the prince's pot belly.

Jade suits were believed to slow decomposition and effectively preserve the body after death. A jade suit unearth in Jiangxi Province was made of roughly 4,000 translucent pieces of jade held together with gold wire. Designed to form fit and cover the body, it has the shape of a robot from 1950s B science fiction movie.

Describing jade suits found in the the Han Tomb of Liu Sheng, Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Although their coffins had collapsed, Liu Sheng and Dou Wan were each found in a well-preserved jade suit. Liu Sheng's was made of 2498 pieces of jade, sewn together with two and a half pounds of gold wire (Dou Wan's was smaller). Each suit consists of 12 sections: face, head, front, and back parts of tunic, arms, gloves, leggings, and feet. It has been estimated that a suit such as Liu Sheng's would have taken ten years to fashion. Along with the jade suits, Liu Sheng and Dou Wan each had a gilt bronze headrest inlaid with jade and held jade crescents in their hands. Archaeologists had known of the existence of jade burial suits from texts, but the two suits found at Mancheng are the earliest and most complete examples ever discovered. During the Han, jade funerary suits were used exclusively for the highest ranking nobles and were sewn with gold, silver, or bronze wire according to rank. The practice was discontinued after the Han.” One of the suits was 188 centimeters long. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Mingqi (Burial Figures)

In ancient times people believed that the souls of the dead lived after death in another world, where they needed all the same things that people need when they were alive. Living animals and people were often slaughtered and buried with people of high status. During the Zhou Dynasty (1122-221 B.C), the custom of killing living beings was replaced with practice of burying people with pottery or wooden burial figures.

By the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), it was common for emperors and other noblemen to decorate their tombs with pottery replicas of warriors, concubines, servants, horses, domestic animals, trees, plants, furniture, models of towers, granaries, mortars and pestles, stoves and toilets, and almost everything found in the real world so the deceased would have everything he needed in the next world.

Heather Colburn Clydesdale wrote: “ Burial figurines of graceful dancers, mystical beasts, and everyday objects reveal both how people in early China approached death and how they lived. Since people viewed the afterlife as an extension of worldly life, these figurines, called mingqi or "spirit utensils," disclose details of routine existence and provide insights into belief systems over a thousand-year period. Mingqi were popularized during the formative Han dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.) and endured through the turbulent Six Dynasties period (221–589) and the later reunification of China in the Sui (589–618) and Tang (618–906) dynasties.[Source: Heather Colburn Clydesdale, Independent Scholar Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Some extraordinarily beautiful sculptures were found in tombs from the state of Chu, which flourished between the 8th and 3rd centuries B.C. in a remote part of China. The Chu produced stylized lacquered deer antlers and a bronze figure with a bird body and serpentine neck. Chu art has brought attention to the fact that non-mainstream and fringe cultures produce art that was a just as beautiful as the art produced by the main Chinese dynasties.

Mingqi in the Han Dynasty

Heather Colburn Clydesdale wrote: “Earthenware mingqi are today the most visible legacy from the Han dynasty due to their durability and number. Although most mingqi were mass produced using molds, they are remarkably animated. Dogs, their ears perked and noses all but twitching, stand alert. Dancers are frozen in mid-step, the alignment of bodies and sweep of sleeves transcending their suspended state to imply the flow of choreography. Drummers succumb to the rhythm of their instruments, kicking up their toes and laughing with joy. This delightful naturalism was central to the figures' purpose of providing the deceased with entertainment, service, and guardianship. [Source: Heather Colburn Clydesdale, Independent Scholar Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Meanwhile, mingqi in the form of buildings and tools provided staples and comforts for the deceased in the tomb. Entire farms complete with granaries, wells, and watchtowers were recreated in miniature. Details like wooden brackets and tile roofs were loyally reproduced, as were regional differences in building styles, ranging from tall towers in the north, courtyard structures in the south, and houses perched on stilts in marshy areas. Since most of their above-ground counterparts were made of wood and have long since disintegrated, mingqi preserve information about architecture in Han China.\^/

“Mingqi worked in concert with other tomb objects and architecture to support a larger funerary agenda, the goal of which was to comfort and satisfy the deceased, who was believed to have two souls: the po, which resided underground with the body, and the hun. While the hun could ascend to the skies, funerary rituals sometimes sought to reunite it with the po in the safer realm of the tomb. Here, valuables such as bronzes, lacquers, and silks, frequently decorated with Daoist imagery, surrounded the coffin. Around the turn of the millennium, Han tomb architectural styles morphed from pits into multichambered underground dwellings, often with elaborate carvings and wall paintings. Constructed of brick and featuring vaulted ceilings, these tombs were aligned along north-south axes and tied to above-ground stone shrines. Many shrines in turn were covered with low-relief carvings depicting paradises and stories underscoring Confucian virtues like filial piety and loyalty.\^/

“In the first century A.D., the site of ritual offerings for the deceased transferred from the shrine to the tomb itself, and people erected large stone statuary of officials and animals along a "spirit path" leading up to the tomb mound. The shrines and spirit paths became an important way for the living to proclaim the deceased family member's and their own commitment to Confucian values. Ultimately, funerary objects such as mingqi worked in concert with other funerary objects, tomb architecture, shrines, and spirit-road sculptures to achieve a goal that exceeded the well-being of the family. According to Confucian doctrine, when every person performed their prescribed social role to perfection, the cosmos would achieve harmony. By ensuring the well-being of the dead, the living promoted accord in the celestial realm and in their own terrestrial existence.\^/

Image Sources: Flying Horse, Brooklyn University; Han tomb, University of Washington; Musicians, All Posters.com; Accupuntcure needle, University of Washington ; Others Nolls website, Wikipedia, Palace Museum Taipei, CNTO; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021