PORCELAIN IN CHINA

Porcelain is a type of pottery made from kaolin, a fine whitish clay composed of quartz and feldspar, that becomes hard, glossy and nearly transparent when it is fired in a kiln. The word "porcelain" reportedly is derived from the Italian word porcella, meaning little pig, or possibly from a similar word meaning female pig genitals. The name was given first to a smooth, white, cowrie shell, and then to the smooth, white finish on porcelain pottery. The term “porcelain” was used in Marco Polo’s writings. Porcelain pieces can be dated by their inscribed reign marks.

Porcelain is a type of pottery made from kaolin, a fine whitish clay composed of quartz and feldspar, that becomes hard, glossy and nearly transparent when it is fired in a kiln. The word "porcelain" reportedly is derived from the Italian word porcella, meaning little pig, or possibly from a similar word meaning female pig genitals. The name was given first to a smooth, white, cowrie shell, and then to the smooth, white finish on porcelain pottery. The term “porcelain” was used in Marco Polo’s writings. Porcelain pieces can be dated by their inscribed reign marks.

"Porcelain" generally refers to an object whose body is made from clay containing kaolin, is covered with a glaze, and is fired at a high temperature so that the body material fuses and the resultant object is impervious to liquids and is resonant when struck. True porcelain is made of fine kaolin clay and feldspar, also known as petuntse or Chinese stone. It is white, thin and transparent or translucent. Before it is shaped the kaolin is mixed, filtered and vacuum pressed into slabs for aging. Blue and white porcelain has traditionally been made from kaolin clay mined near Jingdezhen, a town in southern China, and mixed with a particular kind of cobalt imported from Persia. Other kinds of porcelain include underglaze red, underglaze blue, copper red (used for imperial ceremonies), "sweet-white," peacock blue and celadon green.

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: “Porcelain, as indicated by its popular name of "china," is another major product of China. Earthenware bowls, plates, and vases have been baked from clay by almost all people since time immemorial, but porcelain is justly acclaimed as a product of Chinese genius alone. True porcelain is distinguished from ordinary pottery or earthenware by its hardness, whiteness, smoothness, translucence when made in thin pieces, nonporousness, and bell-like sound when tapped. The plates you eat from, even heavy thick ones, have these qualities and are therefore porcelain. A flower pot, on the other hand, or the brown cookie jar kept in the pantry are not porcelain but earthenware.[Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu]

“Two mineral ingredients are necessary to give porcelain its peculiar characteristics. The first is the white clay known as kaolin. It is an aluminum silica compound which takes its name from the Chinese term kao-ling (gow-ling), meaning "high hill." The latter is the name of a place where the clay was obtained in early times, lying twenty miles northeast of the famous porcelain kilns at Ching-te-chen in Central China. The second essential ingredient in porcelain is petuntse, a mineral resembling kaolin, but more glassy in character. Its name originates from the Chinese term pai-tun-tzu (by-doon-dse), meaning "white bricks." The name describes the brick-like blocks into which this mineral is kneaded by the Chinese porcelain workers before being mixed with kaolin, shaped into various objects, and then baked to become porcelain.

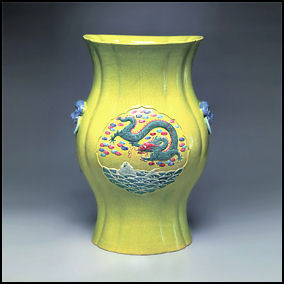

In China, porcelain was produced to be enjoyed on three levels: aesthetic, technical and symbolic. The ways the painted subject on porcelain interact often portrayed a meaning beyond the symbols. A five-claws dragon superimposed on tangerines and pomegranates, for example, links the royal family with fertility (pomegranates) and prosperity (tangerines).

See Separate Article CHINESE CERAMICS factsanddetails.com ; CELADONS factsanddetails.com ; JIANGDEZHEN AND ITS PORCELAIN, KILNS AND GLAZING AND PAINTING TECNIQUES factsanddetails.com ; HAN DYNASTY ART: BRONZE MIRRORS, JADE SUITS AND TOMB FIGURES factsanddetails.com TANG HORSES AND TANG ERA SCULPTURE AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY CERAMICS — PORCELAIN, JU WARE AND CELADON — AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com ; YUAN DYNASTY CRAFTS AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com MING DYNASTY PORCELAIN factsanddetails.com QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: 1) China Museums Online: chinaonlinemuseum.com ; 2) Guide to Chinese Ceramics: Song Dynasty, Minneapolis Institute of Arts; artsmia.org features many examples of different types of ceramic ware produced during the Song dynasty, including ding, qingbai, longquan, jun, guan and cizhou. 3) Making a Cizhou Vessel Princeton University Art Museum artmuseum.princeton.edu. This interactive site shows users seven steps used to create Song- and Yuan-era Cizhou vessels.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Porcelain: “Illustrated Brief History of Chinese Porcelain” by Guimei Yang and Hardie Alison Amazon.com “Chinese Porcelain” by Anthony du Boulay Amazon.com; “Chinese Pottery and Porcelain” By Vainker ( Amazon.com ; Ceramics: “Chinese Ceramics: From the Paleolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty” by Laurie Barnes, Pengbo Ding, Jixian Li, Kuishan Quan Amazon.com “How to Read Chinese Ceramics by Denise Patry Leidy (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Amazon.com; “Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry, and Recreation” by Nigel Wood Amazon.com; Celadons: “Chinese Celadon Wares”by Godfrey St. George Montague. Gompertz Amazon.com “Ice and Green Clouds: Traditions of Chinese Celadon” by Yutaka Mino and Katherine Tsiang Amazon.com; Jingdezhen: “China's Porcelain Capital: The Rise, Fall and Reinvention of Ceramics in Jingdezhen” by Maris Boyd Gillette Amazon.com; “Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum” by Zhu Pei Amazon.com Art: “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com

History of Porcelain in China

The Chinese made the earliest known porcelain around A.D. 700 and held a global monopoly on its production for over a thousand years. Chinese porcelain didn't reach Europe until the 14th century and the art of making porcelain wasn’t developed in Japan until the 16th century and in in Europe until the 17th century. Porcelain from the various Chinese dynasties can be identified by looking at their glaze, motifs, forms, craftsmanship and firing techniques.

Porcelain evolved step-by-step from 5,000-year-old painted pottery through a process of refining materials and manufacturing. A greenish glaze applied to stoneware was developed in the early Han (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) dynasty. A glaze that resembled the sort used on porcelain was made in the early Sui dynasty. Celadons evolved during the Six Dynasties period (A.D. 220-589). It is green porcelain made with a slip and glaze, sometimes with incised and inlaid decorations. It is associated with both China and Korea. Proto-porcelain evolved during the Tang dynasty. It was made by mixing clay with quartz and the mineral feldspar to make a hard, smooth-surfaced vessel. Feldspar was mixed with small amounts of iron to produce an olive-green glaze.

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: ““The word tz'u, which is the present-day Chinese term for porcelain, occurs for the first time in the poem of a Chinese writer who died in the year A.D. 300. This poem speaks of a wine pot which is said to be of "blue-green tz'u." Yet it is unlikely that the new word here refers to a genuine porcelain. Several centuries were still to elapse before patient experimentation gradually evolved the real porcelain with which we are familiar today. In this experimentation it is probable that Chinese alchemists played a vital part. In their eager search for the elixir of immortality, they carried on constant experiments with many kinds of minerals, of which kaolin seems to have been one. Thus kaolin is mentioned in Chinese literature as a medicinal drug before it is referred to in connection with porcelain itself. Incidentally, it is not at all impossible that this Chinese alchemy was the inspiration of the alchemy of the Arabs and, through it, of medieval European alchemy, from which our modern chemistry eventually comes. [Source: Derk Bodde, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei:“ The art of porcelain-making “reached its pinnacle during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The town of Jingdezhen (Jingde Zhen, Ching-te-chen), in Jiangxi province, became the center for imperial Ming kilns and still is known for its excellent porcelain production. By comparison, the English did not 'discover' the secret of making hard-paste porcelain until the mid-18th century. During the 16th century, traders transported tens of millions of pieces of Ming - and later, Qing porcelain to the West. Chinese porcelain techniques and designs greatly influenced future developments in European and Near Eastern ceramic wares. The Ming blue and white porcelain was highly prized by wealthy Chinese, Europeans, Arabs and Asians - which led to an explosion in the trade of the porcelain wares. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Pottery Versus Porcelain

Major difference between pottery and porcelain: 1) pottery is made with ordinary clay with an iron content higher than three percent and fired at temperatures less than 1000 degrees C, using a low-temperature glaze or no glaze at all; 2) porcelain is made with porcelain stone and clay with an iron content of less than three percent. It is fired at temperatures above 1200 degrees C using a high-temperature glaze that also works at temperature over 1200 degrees C.

Major difference between pottery and porcelain: 1) pottery is made with ordinary clay with an iron content higher than three percent and fired at temperatures less than 1000 degrees C, using a low-temperature glaze or no glaze at all; 2) porcelain is made with porcelain stone and clay with an iron content of less than three percent. It is fired at temperatures above 1200 degrees C using a high-temperature glaze that also works at temperature over 1200 degrees C.

Pottery and porcelain are materials made from earth and water and their forms are shaped by kneading clay. Due to firing, changes occur to the physical as well as the chemical properties of clay. Materials used to make pottery are easy to obtain and high temperatures are not required in the firing process. As a result, most ancient civilizations in the world are known to have produced pottery with their own unique characteristics. Due to its porous nature, pottery is permeable even when covered by a coat of low-fired glaze. When struck, pottery makes a dull sound. In ancient china, pottery was often used as building material, or for the creation of funerary objects and containers for sauces, minced meat, wine, and water. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Porcelain are made from a refined clay known as kaolin, that is first covered with a coat of gloss glaze, then fired at high temperatures. Abundant in kaolin clay, China was among the earliest civilizations to discover the secret of firing kaolin. Over time, varieties such as green wares and white wares appeared as different techniques developing gradually such as the application of under glaze and over-glaze, incised or pattern-imprinted moulds used to create decorative motifs. When stuck, they make a clear sound. Porcelain wares generally serve as dining utensils, containers, and decorations for display. They are also often used at ceremonies and religious events.

After sintering, the body and glaze of ceramics do not deteriorate easily as time goes by. As a result, shards from ancient sites can be seen as records of remote cultures. Researchers are also able to learn about ceramic-making techniques of various regions in different time periods by observing the marks left during the processes of production

Porcelain-Making Techniques and Types of Kilns

Porcelain-Making Techniques and Kilns: 1) Pulling clay to form an object: To put the kneaded clay on the center of the potter’s wheel, then to pull the clay to form an object while the wheel is moving. 2) Trimming: To put the dry object upside down on the wooden stake in the center of the wheel, then to trim the surface of the body with a knife. 3) Impressing: To put the half-dry object on the clay model, then to revolve the object slowly and pat it at the same time. This is a special process for round objects. 4) Glazing: To coat the object with glaze. Round objects are usually glazed in two ways: the inside and the bottom are glazed with the shaking method; the outside is glazed with the dipping method. 5) Painting (underglaze blue): To paint various designs on the surface of the finished objects with blue pigment by brush. Usually, the inside wall is painted and glazed before the outside wall is painted. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Mantou Kiln (or round kiln) is a type kiln traditionally found in north China. It is named for its shape, like a steamed bun. The earliest examples, derived from the primitive cave kilns, were built in the early Shang period (ca. 16th — 11th century B.C.). It developed into a semi-down-draft kiln in the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907), and matured in the Song dynasty (A.D. 960-1127). The firing, in reduction or oxidation flame with coal as fuel, could reach 1300 degrees Celsius. The model here shows a mantou kiln in Shaanxi area of the Northern Song dynasty (A.D. 960-1127).

Egg-shaped Kiln (or cai kiln), shaped like half an egg lying horizontally, is a type long used at Jingdezhen. It developed from the gourd-shaped kilns of the late Yuan and early Ming period, and became especially popular in the Ming period. The kiln is 7-18 meters long, high and wide in the front, low and narrow in the rear. The firing is in reduction flame with wood as fuel. The model here shows the front part of Jingdezhen’s egg-shaped kiln of the Qing dynasty (A.D. 1644-1911).

Dragon Kiln is a type mostly seen in southern China since antiquity. It is shaped like a dragon. The earliest known examples date from the Shang period (ca. 16th — 11th century B.C.), and the well improved ones appeared in the Song period (A.D. 960-1279). The dragon kiln was usually built on the side of a hill, rising at an angel of 8 to 20 degrees with a length of 30-80 meters, and had a natural draught easy for temperature raising. The firing, with wood as fuel, is mainly in reduction flame. The model here shows a part of the dragon kiln in Zhejiang area of the Song dynasty (A.D. 960-1279).

Development of Porcelain Painting

Porcelain has been made in China since the 8th century AD, during the Tang Dynasty. In the 13th century, during the Yuan Dynasty, Chinese porcelain artisans were exposed to Persian hand-painted ceramic wares, which utilized bright blue colors. When cobalt blue (sometimes referred to as Mohammed blue) was obtained by the Chinese in the 14th and 15th centuries from Persian sources, Chinese potters perfected a method of painting with the cobalt blue under a transparent glaze. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

The blue cobalt pigment is applied through decorative brush painting by highly skilled artisans directly on the biscuit (pre-kiln baked clay which has been molded into various items) before glazing. After firing in the kiln, the pigment melts in between the biscuit and glaze creating a crystalline glaze and the bluish designs. Ming artists also excelled in painting over the glaze, using brilliant enamel colors.

Chinese porcelain was strikingly different from the pottery made in Europe in the same period. The porcelain paste was translucent, and when tapped it rang like glass. It was admired for its whiteness and the fact that although it was much thinner than pottery, it was at the same time much harder and did not easily crack or chip. Moreover the designs were bright and the glaze did not wear away with use.

During the Ming dynasty the flourishing of culture led to the painting techniques were very delicate and elegant, resulting in highly artistic and very fine quality blue-and-white porcelain. Ancient Chinese techniques of brush painting were used to decorate the distinctive Ming ceramic wares. Designs chosen for the various pieces were based on the symbolism so prevalent in Chinese culture and arts. Other important developments in porcelain production during the Ming dynasty included the wide usage of multicolor glaze, and the practice of putting the artist's signature, kiln's title and the year the piece was made at the bottom of each piece.

Proto-Porcelain in the Shang and Zhou Dynasties

A fine white pottery was made during the Shang Dynasty (1766-1122 B.C.) . Many vessels were similar in size and shape to bronze vessels made during the same period. Scholars believe the bronze vessels were likely copies of ceramic vessels.

According to the Shanghai Museum:“Proto-celadon appeared no later than the Shang period and was produced in large quantities during the periods of the Western Zhou, the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States ((11th-3rd century B.C.). In the second and first centuries B.C. production declined. Proto- celadon contains essential features of porcelain but still displayed some primitive characteristics, which represented the initial stage of porcelain production. The quality was not that great as water absorptivity was high and there were many air bubble. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

“Glazed high-fired porcelain first appeared in the Shang dynasty. By the late Spring and Autumn period, ritual and ceremonial wares with evenly applied green glaze developed in the Zhejiang area. However, large-scale production of porcelain did not begin until the Three Kingdom period and the Jin dynasties. As porcelain became associated with refined tastes and grew in popularity among high-ranking officials, ci, the Chinese character for porcelain, began to appear in poetry and essays.

“Celadon Zun (wine vessel) with String Pattern”, at the Shanghai Museum, is an example of proto-porcelain and early celadon porcelain. It is molded with clay with an iron content of about 2 percent, and then fired in 1200 high temperature after manual glazing. This Zun looks noble and stylish in both shape and glaze and shares the same style with the pottery unearthed from the tombs of Yin Ruins Culture, Shang dynasty. It should be the drinking vessel used by the Shang royal family and a typical proto-porcelain of the Shang dynasty.

Celadons

Celadon is a bluish, grayish green porcelain made with a slip and glaze, sometimes with incised and inlaid decorations. Evolving during the Six Dynasties period (A.D. 220-589), it is associated with both China and Korea.. The color of celadon results from natural iron oxide in the glaze, which produces the green hue when fired in a reducing atmosphere kiln.

Soyoung Lee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The term celadon is thought to derive from the name of the hero in a seventeenth-century French pastoral comedy. The color of the character Céladon’s robe evoked, in the minds of Europeans, the distinctive green-glazed ceramics from China, where celadon originated. Some scholars object to such an arbitrary and romanticized Western nomenclature. Yet the ambiguity of the term celadon effectively captures the myriad hues of greens and blues of this ceramic type. [Source: Soyoung Lee, Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003]

Some of the most beautiful porcelain ever produced was made during the Song dynasty (960-1279), when world-famous monochrome porcelains, including celedon, were produced. Ju ware, a kind of celadon from the Northern Song dynasty that ranges in color from blue to green, is the rarest of all forms of porcelain. Only 65 pieces of it exist and 23 of them are possessed by the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

See Separate Article CELADONS factsanddetails.com

First Real Porcelain

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: “The first description that seems to point definitely to porcelain from a source outside China is that of the famous Arabic traveler, Suleyman, in his account dated 851 of travels in India and China. There he speaks of certain vases made in China out of a very fine clay, which have the transparency of glass bottles. [Source: Derk Bodde, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ During the Sui and Tang dynasties (581-907), kilns thrived in both northern and southern China. White-glazed porcelains from the Hsing kilns in Hebei as well as the Ting kilns enjoyed broad popularity. Anhwei, Hunan, and Shanxi were especially known for their celadons. The Yüeh-chou region, an area surrounding present-day Lake Shang-lin in Tz'u-hsi County, Zhejiang, was the reigning center of porcelain production. Wares of the region delivered to the imperial court after the mid-Tang were characterized by a quality called "mi-se (mysterious color)". [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

The culture of drinking tea predominated during the Sui and Tang (581-907), and descriptive phrases on porcelains abounded, such as "the white glaze of Hsing wares glistens like silver and is as white as snow," and "the glaze of Yüeh celadons is green like jade and as translucent as ice." The appreciation of porcelain rose to the level of passionate debate, and porcelains were discussed in formulations of aesthetic theory. Multi-colored splashed glazes and painting found on the surface of Ch'ang-sha wares brought even greater attention to the study of ceramics and porcelains and to further invention in the realm of their imaginative embellishment.

“The ruling house of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) doted on refinement and the elegant accoutrements of culture, and it accordingly gave priority to the fine arts. Under this stimulation, the manufacture of porcelain progressed, and it was at this time that several famous types of wares were produced. From the Tang dynasty (618-907) into the Sung, Ting ware succeeded Hsing ware, Lung-ch'uan ware carried on the tradition of Yuah ware, and both the white wares and the green wares made great strides in terms of quality and quantity. In addition, the production of dignified shapes and harmonious glazes reached a full maturation in Kuan ware, Ju ware, Ko ware, and Chua ware. The porcelain industry at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province was also forging ahead at this time with Ying Qing wares, white wares and Tz'u-chou type wares being sold throughout the north. Pieces with black ground and white decoration or white ground and black decoration are particularly lively and exuberant, expressing the special spirit of the people. Among the black-glazed wares, Chien wares from Fujian province and Chi-chou wares from Jiangxi province are the most famous.

Jiangdezhen

Jiangdezhen (140 kilometers northeast of, and 2½ hours by train, from Nanchang) is regarded as the "Porcelain Capital of China" and has been called the "Porcelain City" of China. The home of a centuries-old porcelain industry, it produces four famous kinds of porcelain: "blue and white," "rice pattern," "family rose" and "monochrome and polychrome glaze." Many other kinds of porcelain and porcelain sculptures are also produced here.

Jingdezhen was known in the Song period (960–1279) for its bluish-white qingbai porcelain, which rapidly came to dominate porcelain production after it began to mass-produce underglaze blue in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). “Vase with Underglaze Blue Design of Interlaced Peonies” is a piece at the Shanghai Museum that dates to the Yuan period. According to the museum: Decorated with blue-and-white patterns all over with rich layers, this vase is an exquisite work of underglaze blue porcelain of the Yuan dynasty. The Yunjian design of the decoration band on the shoulder is almost at the same level of the band of interlaced branches and peony sprays at the belly part, highlighting two different themes. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Located on the eastern bank of the Yangtze River and bordering Anhui province to the north, Jiangdezhen is where porcelain was invented and first fired from kaolin clay mined nearby. Official kilns dedicated to the production of imperial wares were established at Jingdezhen in the early Ming period, and these kilns introduced a large number of fine wares. In the Qing period many more new wares were created, drawing on the long experience of both folk and imperial kilns. By that time Jingdezhen was famous for porcelain throughout the world.

See Separate Article JIANGDEZHEN AND ITS PORCELAIN, KILNS AND GLAZING AND PAINTING TECNIQUES factsanddetails.com

Porcelain from Places Other Than Jiangdezhen

According to the Shanghai Museum:“Famous products include white Dehua wares from Fujian Province, Yixing Zisha ("purple clay") wares from Jiangsu Province,Shiwan wares from Guangdong Province,and white Zhangzhou wares from Fujian Province. In northern China,Fahua pottery in Shanxi Province and porcelain of Cizhou kiln in Hebei Province were also well known for their mass production. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

“White Glazed Statue of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva with ‘He Chaozong’ Mark” is an example of Dehua white-glazed ware of the Ming dynasty. It has a yellowish glaze taking on a color of milk white and a texture of smooth and plump, enjoyed high popularity among European people, also reputed as ivory white, lard white, China white and so on. Dehua porcelain of the early Ming usually takes on flesh pink, translucent under the light, and shows delicate and crystal luster like glutinous rice under a magnifying glass.

He Chaozong, also known as He Lai, was a Chinese porcelain artist in the Ming dynasty. With an elegant, solemn and generous style, He Chaozong’s work presents a strong feeling of texture. Depending solely on the beauty in sculpture and in the texture of the glaze and body other than applying color glaze, his statue finds nothing comparable in the porcelain world. His work absorbed strengths of ancient sculpture works, especially the art style of Tang Buddha statues. The statues of Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara and Bodhidharma he created are full of the charm of the Tang dynasty, with the image looking dignified and solemn, as well as approachable. This is one of his masterpieces.

“Kettle in Shape of a Semi-circular Roof Tile Designed” by Chen Mansheng in Yixing This teapot was a ‘Mansheng Pot’ jointly made by famous seal artist Chen Hongshou and renowned Zisha kettle artist Yang Pengnian of the Qing dynasty. Chen Hongshou, literary named Mansheng, was a famous Zhejiang School seal artist of the Qing dynasty. Since he was passionate for Zisha craft, he asked the famous craftsman Yang Pengnian to make Zisha kettles based on his own design and carved the inscription on the pot in person, known as ‘Mansheng Pot’. This teapot imitates the shape of a roof tile of the Han dynasty and is inscribed with Han roof tile script. Featuring primitive and elegant modelling, refined, stiff and smooth craftsmanship, with its fluent lines and mild texture, the teapot possesses a strong culture identity.

Song Dynasty Porcelain

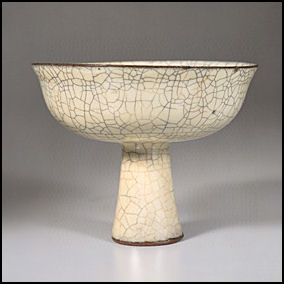

Some of the most beautiful porcelain ever produced was made during the Song dynasty (960-1279), when world-famous monochrome porcelains, including celadon, were produced. Celadon is green porcelain made with a slip and glaze, sometimes with incised and inlaid decorations. It is associated with both China and Korea. Wonderful crazed or cracked glazed pottery, produced by the shrinking and cracking of the glazes due to rapid cooling, appeared during the Song period. The earliest pieces with this kind of glazing were probably made by accident in the firing process but later was developed into an art form that had a great impact outside of China, influencing the famous tea ceremony ceramics of Japan. Ju ware, a kind of celadon from the Northern Song dynasty that ranges in color from blue to green, is the rarest of all forms of porcelain. Only 71 pieces of it exist and 23 of them are possessed by the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

In the time of the Liao, Song and Jin dynasties (10th — 13th century) major porcelain-making kilns were widely distributed in both the south and the north. In addition to celadon and white porcelain, many other wares were popular, such as qingbai (porcelain with a bluish-white glaze), black-glazed ware, and porcelain with painted designs. A wide variety of porcelain-making techniques competed vigorously. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

According to the Shanghai Museum:“ During the Song dynasty, five well known kilns, Ru, Guan, Ge, Ding and Jun, manufactured exquisite porcelain wares for royal families. In addition, folk kilns both in the south and the north produced many unique wares of high quality. Porcelain manufacture of the Liao and Xi-Xia regimes in northern China provided many distinctive products with ethnic style and craftsmanship. Meanwhile, production of blue-white porcelain at the Jingdezhen greatly promoted its position in China. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “After the Sui and Tang dynasties, the spread of kiln firing technique allowed for porcelain to become available to both the rich and the poor. Amongst the most popular were the green wares of the Yue kilns in the South and the white wares of the Xing kilns in the North. Furthermore, Ding ware and Changsha ware were exported in large quantities, reaching as far as Egypt and Mesopotamia. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

The ruling house of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) doted on refinement and the elegant accoutrements of culture, and it accordingly gave priority to the fine arts. Under this stimulation, the manufacture of porcelain progressed, and it was at this time that several famous types of wares were produced. From the Tang dynasty (618-907) into the Sung, Ting ware succeeded Xing ware, Lung-ch'uan ware carried on the tradition of Yuah ware, and both the white wares and the green wares made great strides in terms of quality and quantity. In addition, the production of dignified shapes and harmonious glazes reached a full maturation in Kuan ware, Ju ware, Ko ware, and Chua ware. The porcelain industry at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province was also forging ahead at this time with Ying Qing wares, white wares and Tz'u-chou type wares being sold throughout the north. Pieces with black ground and white decoration or white ground and black decoration are particularly lively and exuberant, expressing the special spirit of the people. Among the black-glazed wares, Chien wares from Fujian province and Chi-chou wares from Jiangxi province are the most famous. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

See Separate Article: SONG DYNASTY CERAMICS — PORCELAIN, JU WARE AND CELADON — AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Yuan Porcelain

In the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) floral motifs and cobalt blue paintings were made under a porcelain glaze. This was considered the last great advancement of Chinese ceramics. The cobalt used to make designs on white porcelain was introduced by Muslim traders in the 15th century. The blue-and-white and polychrome wares from the Yuan Dynasty were not as delicate as the porcelain produced in the Song dynasty. Multi-colored porcelain with floral designs was produced in the Yuan dynasty and perfected in the Qing dynasty, when new colors and designs were introduced.

With the invention of underglaze blue porcelain in the Yuan period (1271-1368), Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province made itself the pre-eminent center for porcelain production, a position it held throughout the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. Celadon and white porcelain were superseded by porcelain with decoration painted under or over the glaze and by various wares with monochrome glazes. Porcelain decoration became richer and more colorful than ever before. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: In the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) Jingdezhen became the center of porcelain production for the entire empire. Most representative of Yuan dynasty porcelain are the underglaze blue and underglaze red wares, whose designs painted beneath the glaze in cobalt blue or copper red, replaced the more sedate monochromes of the Song Dynasty. At the same time, from the standpoint of the shape of the objects, Yuan dynasty porcelains became thick, heavy, and characterized by great size, transforming the refinement of Song Dynasty shapes. From this we can get some idea of the differences between the eating and drinking customs of the Sung and Yuan dynasties. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

During the Song, Jin and Yuan dynasties from the tenth to fourteenth centuries, the firing of stoneware are widespread. Famous stonewares were named after the locations at which they were produced. Various kilns in different places came to establish their own independent styles as each excelled in the forms, glazes, skills for decorating and techniques of production for which they became known.

The world record price paid for an art work from any Asian culture is $27.8 million, paid in March 2005 for a 14th century Chinese porcelain vessel with blue designs painted on a white background. The vessel contains scenes of historical events in the 6th century B.C. and has unique Persian-influenced shape. Only seven jars of this shape exist in the world. The buyer was Giuseppe Eskenazi., the renowned dealer of Chinese art, acting on behalf of a client. The previous record for porcelain was $5.83 million paid for a14th-century blue-and-white porcelain vessel called the pilgrims vessel in September 2003.

See Separate Articles YUAN DYNASTY CRAFTS AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com

Ming Porcelain

Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) ceramics were known for the boldness of their form and decoration and the varieties of design. Craftsmen made both huge and highly decorated vessels and small, delicate, white ones. Many of the wonderful decorations and glazes — peach bloom, moonlight blue, cracked ice, and ox blood glazes; and rice grain, rose pink and black decorations —were inspired by nature.

In 1402, the Ming Emperor Jianwen ordered the establishment of an imperial porcelain factory in Jingdezhen. It's sole function was to produce porcelain for court use in state and religious ceremonies and for tableware and gifts. Between 1350 and 1750 Jiangdezhen was the production center for nearly all of the world's porcelain. Jiangdezhen was located near abundant supplies of kaolin, the clay used in porcelain making, and fuel needed to fire up kilns. It also had access to China's coast, which was used for transporting finished products to places in China and around the world. So much porcelain was made that Jingdezhen now sits on a foundation of shards from discarded pottery that over is four meters deep in places.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The imperial porcelain factory was established at Jingdezhen at the beginning of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), and from this time the position of Jingdezhen as the center of porcelain production became consolidated. The imperial wares that were specially manufactured for use at court were made particularly exquisitely and were marked with the reign mark of the emperor himself. In addition to the monochromes and the underglaze blue porcelains that continued to be produced among the official wares of the Ming dynasty, innovations appeared throughout the period.Ceramic production was an important state affair in the Ming dynasty. In early Ming, the ceramics industry was mainly based at the Longquan kilns in Zhejiang province and the Jingdezheng kilns in Jiangxi province. Their products not only circulated all over China but also reached overseas markets. Furthermore, both of these kiln sites produced official wares. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

See Separate Article MING DYNASTY PORCELAIN factsanddetails.com

Qing Porcelain

Qing dynasty (1644-1912) porcelain was famous for its polychrome decorations, delicately painted landscapes, and bird and flower and multicolored enamel designs. Many of the subject had symbolic meanings. The work of craftsmen reached a high point during the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722)

During a rebellion in 1853, the imperial factory was burned. Rebels sacked the town and killed some potters. The factory was rebuilt in 1864 but never regained its former stature. With the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912, the long history of Chinese porcelain making drew to a close.

Image Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, McClung Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021