CHINESE CERAMICS

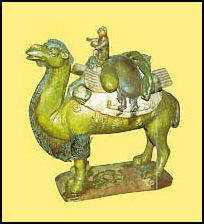

Tang Camel

China has long been known throughout the world as the home of porcelain, known to many as China. Its porcelain has been exported continuously since the A.D. eighth century. In Shakespeare’s "Measure for Measure" (ca. 1600) a character says, ‘They are not China-dishes, but very good dishes,’ demonstrating that even back then Chinese porcelain was equated with quality. See Separate Article on Porcelain factsanddetails.com

Chinese ceramics is famous for its exquisite forms, shapes, finishes and delicate use of color. Early in China’s history it was raised above utilitarianism to a fine art. Great works of art were patronized by the imperial court and the upper classes and sought after outside of China in Europe and other places. According to the Shanghai Museum: Ancient ceramic includes pottery from the Neolithic period, proto-type celadon of the Shang, the Zhou, the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States periods, fine celadon of the Eastern Han and famous polychrome-glazed pottery of the Tang dynasty. During the Liao, the Song, and the Jin dynasties, celadon kilns emerged in various places of China. Green, white, black-glazed ware and porcelain with painted designs became popular, thus a wide variety of porcelain blossomed in lots of color. Throughout the Yuan, the Ming and the Qing dynasties, Jingdezhen was the center of porcelain production and its exquisite products became well known all over the world.[Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

Famous Chinese ceramic include include renowned Song wares, doucai porcelains of the Chenghua reign in the Ming dynasty, painted enamel porcelains of the High Qing as well as official wares of various Ming and Qing dynasty reigns. From the perspective of various glaze colors, it is possible to see how glazes evolved at different kilns and periods as well as how official models of decoration formed over time. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Connoisseurship of Chinese ceramics can take the two main approaches: vessel shape and glaze. From the time a form appears to its transformation also involves changes in period style. Likewise, glaze color and decoration can reflect official or market taste. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“ The "Neolithic Age to the Five Dynasties" represents a long period of time when ceramics evolved from primitive beginnings to a more sophisticated stage. Using the perspective of daily aesthetics, "Song to Yuan Dynasties" explores the decorations and beauty of various wares from different kilns. The "Ming Dynasty" period narrates the establishment of the Jingdezhen imperial kilns, as porcelain production became a state affair and local civilian kilns competed for market share. The "Qing Dynasty" was a time when three emperors, Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong, personally gave orders for the imperial kilns, the influence of official models reaching a peak at that time. As the dynasty began to decline, the styles of folk art began to creep into late Qing imperial wares.

See Separate Article PORCELAIN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CELADONS factsanddetails.com ; JINGDEZHEN AND ITS PORCELAIN, KILNS AND GLAZING AND PAINTING TECNIQUES factsanddetails.com ; HAN DYNASTY ART: BRONZE MIRRORS, JADE SUITS AND TOMB FIGURES factsanddetails.com TANG HORSES AND TANG ERA SCULPTURE AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY CERAMICS — PORCELAIN, JU WARE AND CELADON — AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com ; YUAN DYNASTY CRAFTS AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com MING DYNASTY PORCELAIN factsanddetails.com QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: 1) China Museums Online: chinaonlinemuseum.com ; 2) Guide to Chinese Ceramics: Song Dynasty, Minneapolis Institute of Arts; artsmia.org features many examples of different types of ceramic ware produced during the Song dynasty, including ding, qingbai, longquan, jun, guan and cizhou. 3) Making a Cizhou Vessel Princeton University Art Museum artmuseum.princeton.edu. This interactive site shows users seven steps used to create Song- and Yuan-era Cizhou vessels.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Ceramics: “Chinese Ceramics: From the Paleolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty” by Laurie Barnes, Pengbo Ding, Jixian Li, Kuishan Quan Amazon.com “How to Read Chinese Ceramics by Denise Patry Leidy (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Amazon.com; “Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry, and Recreation” by Nigel Wood Amazon.com; Celadons: “Chinese Celadon Wares”by Godfrey St. George Montague. Gompertz Amazon.com “Ice and Green Clouds: Traditions of Chinese Celadon” by Yutaka Mino and Katherine Tsiang Amazon.com; Porcelain: “Illustrated Brief History of Chinese Porcelain” by Guimei Yang and Hardie Alison Amazon.com “Chinese Porcelain” by Anthony du Boulay Amazon.com; “Chinese Pottery and Porcelain” By Vainker ( Amazon.com ; Jingdezhen: “China's Porcelain Capital: The Rise, Fall and Reinvention of Ceramics in Jingdezhen” by Maris Boyd Gillette Amazon.com; “Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum” by Zhu Pei Amazon.com Art: “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com

Early History of Pottery

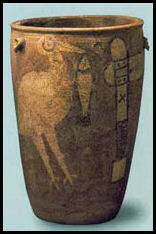

Yangshou vessel

3300 B.C.According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““Ceramics is a sign of civilization. From processing the clay, shaping the forms, applying the glazes to firing the products in kilns, raw materials go through many changes as soft clay becomes durable ceramic. The forms, glazes and decorative patterns on ceramics are diverse and varied due to their being created under different cultural and social conditions. Emperors, officials, potters and users of ceramics all contributed to the formation of various period styles. What is attractive about ceramics is that it echoes and records the long course of history, the network development of kilns also reflecting the phenomenon of cross-cultural interactions that took place over time. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

The craft of making ceramics and clay vessels is one of the oldest human arts. Pottery is made by cooking soft clay at high temperatures until it hardens into an entirely new substance — ceramics. Early pottery vessels were used primarily for storing liquids, grains and other items. Clay pots were used for cooking and storage. Pottery from Japan dated to 10,000 B.C. was long thought to be the oldest known ceramics in the world but older pottery has been found in China (See Below). Nine thousand year old sites in Turkey with ancient pottery have yielded mostly bowls and cups.

Potters first fired vessels in hearths, and afterwards in kilns. Kilns are special structures made of bricks or stones in which temperatures of at least 1,050̊C can be generated. Firing ceramics at high temperatures improves their durability and impermeability and creates greater opportunities for changing the surface color. Common ways of decorating pottery included printing selected areas, covering the surfaces with a thin slip made of iron-rich red clay, and burnishing (compacting the surface with a hard, tool such as a pebble).

The first pottery vessels were fashioned by hand from lumps of clay. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in 4000 B.C. With a potter’s wheel, a lump of clay can be spun around and round, shaped, usually into a vessel, with the hands and a variety of tools. To make a pottery vessel, a potter must find the right clay, and purify and cure it to make it usable. Raw clays have traditionally been put into large vats to remove foreign matter such as sand and pebbles. When clay is washed these materials settle to the bottom while the clay remains suspended and is poured off. Clay washed in this manner is known as slip.

Early Pottery in China

At places in both the Yellow River valley and the Yangtze River valley handmade pottery from as early as the 6th millennium B.C. has been unearthed. Some of the earliest examples of pottery in China, dating back to 6000 B.C. , were created by the "Yangshao Culture," (named after village near the confluence of the Yellow, Fen and Wei rivers where the artifacts were found). Some of these clay vessels have painted flowers, fish, human faces, vaginas and geometric designs. Beginning around 3500 B.C., the Lungshan Culture (named after a village in Shandong province where the artifacts were found) produced white pottery and "eggshell-thin" black pottery. Multi-colored and burnished black pottery appeared in Neolithic times in settlements along the upper, middle and lower reaches of the Yellow and Yangtze River.

One of the earliest methods of pottery making was building up a vessel by winding up a clay chord. First the maker rolled wet clay or mud into a long snake-like cord and wound it up from bottom to top to shape the vessel and then smoothed the surface by striking it with bat and forging it. The pottery wheel was used at least as far back as the Dawenkon Culture (2800-2400 B.C.) to produce lovely black pottery stem cups and other objects, The Chinese pottery wheel is thought to have been a round working table with a central hole on an axle that could be spun at a relatively high speed, The potter put the pottery on the center of the table and spun the wheel and shaped vessels with tools or by hand.

Advancement in firing techniques lead to new types of pottery such as high-fired stoneware and glazed stoneware developed during the Shang (1766-1122 B.C.), Zhou (1122-221 B.C.), Qin (221-206 B.C.) and Han (206 B.C.” A.D. 220) dynasties. In the Shang period a high-fired glazed ware (proto-porcelain) appeared. The stoneware called mature celadon was first made in the first century A.D. (late Han dynasty) and was steadily improved at southern kilns over the next few centuries (the Three Kingdoms, Western Jin, and Eastern Jin dynasties and the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, A.D. 220-589). [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

World’s Oldest — 20,000-Years-Old — Pottery Found in a Chinese Cave

In 2012, Pottery fragments found in a south China were confirmed to be 20,000 years old, making them the oldest known pottery in the world. The findings, which appeared in the journal Science, was part of an effort to date pottery piles in east Asia and refutes conventional theories that the invention of pottery correlates to Neolithic Revolution, a period about 10,000 years ago when humans moved from being hunter-gathers to farmers. [Source: Didi Tang, Associated Press, June 28, 2012 /+/]

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The invention of pottery for collecting, storing, and cooking food was a key development in human culture and behavior. Until recently, it had been thought that the emergence of pottery was part of the Neolithic Revolution around 10,000 years ago, which also brought agriculture, domesticated animals, and groundstone tools. Finds of much older pottery have put this theory to rest. This year, archaeologists dated what is now thought to be the oldest known pottery in the world, from the site of Xianrendong Cave in the Jiangxi Province of southeastern China. The cave had been dug before, in the 1960s, 1990s, and 2000, but the dating of its earliest ceramics was uncertain. Researchers from China, the United States, and Germany reexamined the site to find samples for radiocarbon dating. While the area had particularly complex stratigraphy — too complex and disturbed to be reliable, according to some — the researchers are confident that they have dated the earliest pottery from the site to 20,000 to 19,000 years ago, several thousand years before the next oldest examples. “These are the earliest pots in the world,” says Harvard’s Ofer Bar-Yosef, a coauthor on the Science paper reporting the finds. He also cautions, “All this does not mean that earlier pots will not be discovered in South China.” [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2013]

AP reported: “The research by a team of Chinese and American scientists also pushes the emergence of pottery back to the last ice age, which might provide new explanations for the creation of pottery, said Gideon Shelach, chair of the Louis Frieberg Center for East Asian Studies at The Hebrew University in Israel. "The focus of research has to change," Shelach, who is not involved in the research project in China, said by telephone. In an accompanying Science article, Shelach wrote that such research efforts "are fundamental for a better understanding of socio-economic change (25,000 to 19,000 years ago) and the development that led to the emergency of sedentary agricultural societies." He said the disconnection between pottery and agriculture as shown in east Asia might shed light on specifics of human development in the region. /+/

See Separate Article NEOLITHIC CHINA factsanddetails.com

Neolithic Pottery in China

Cermaic black pottery cup,

Liungshan Culture 2600 2000 B.C.

According to the Shanghai Museum:“Pottery was an important innovation of the Neolithic Age. Along with domestication and sedentary life, ancient people learned how to make pottery. Neolithic archaeological sites and cultures have been found all over China. Distinctive workmanship and decoration of Neolithic pottery became representatives of different cultures in time and space. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net =]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ In the late Neolithic Age, various regions produced an assortment of ceramics, displaying the dynamic spirit of these early peoples. For example, the Yangshao culture, located at the upper reaches of the Yellow River, produced pottery painted with geometric patterns in bright colors such as red, black, and white, while in the lower reaches, the Longshan culture featured lustrous, black pottery characterized by its thin, eggshell-like form. The Dawenkou culture also manufactured very fine and meticulous white colored pottery. Through these examples, it is clear that the knowledge for selecting materials and the techniques for shaping forms and kiln firing were advanced, allowing for the development of diverse aesthetic ideas. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Painted Pot with Swirls Design”, a piece in the Shanghai Museum, is named after the excavated Banshan Tomb in Gansu province, Banshan Type is the most typical pottery of Majiayao Culture with a history of about 4,300 to 4,600 years. Banshan Type painted pottery usually adopts black paints, mainly featuring various geometrical patterns, many of which are edged with black saw-tooth design in sleek and dynamic lines, presenting a vivid aesthetic feeling of primitive art. The pottery with its fine and smooth paste, full and plump shape and dense and complex pattern, possesses the typical features of Banshan Type painted pottery. =

“Jar with a High Handled Lid” was made by the Liangzhu Culture (3300-2250 B.C.), which flourished in present-day Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shanghai and other areas was so named since it was discovered in Liangzhu, Yuhang, Zhejiang province in 1936. Pottery ware of this kind is best represented by black pottery made of grey clay, bright and refined surface as well as unique and structured shape, a minority of the pieces being carved with meticulous and smooth patterns. This jar has a delicate shape and pitch-dark shiny surface with several wide painted reddish-brown lines, the ring foot of which is decorated with three sets of openwork geometric patterns. =

Proto-Porcelain in the Shang and Zhou Dynasties

A fine white pottery was made during the Shang Dynasty (1766-1122 B.C.) . Many vessels were similar in size and shape to bronze vessels made during the same period. Scholars believe the bronze vessels were likely copies of ceramic vessels.

According to the Shanghai Museum:“Proto-celadon appeared no later than the Shang period and was produced in large quantities during the periods of the Western Zhou, the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States ((11th-3rd century B.C.). In the second and first centuries B.C. production declined. Proto- celadon contains essential features of porcelain but still displayed some primitive characteristics, which represented the initial stage of porcelain production. The quality was not that great as water absorptivity was high and there were many air bubbles. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

“Glazed high-fired porcelain first appeared in the Shang dynasty. By the late Spring and Autumn period, ritual and ceremonial wares with evenly applied green glaze developed in the Zhejiang area. However, large-scale production of porcelain did not begin until the Three Kingdom period and the Jin dynasties. As porcelain became associated with refined tastes and grew in popularity among high-ranking officials, ci, the Chinese character for porcelain, began to appear in poetry and essays.

“Proto-Celadon Zun (wine vessel) with String Pattern”, at the Shanghai Museum, is an example of proto-porcelain and early celadon porcelain. It is molded with clay with an iron content of about 2 percent, and then fired in 1200 high temperature after manual glazing. This Zun looks noble and stylish in both shape and glaze and shares the same style with the pottery unearthed from the tombs of Yin Ruins Culture, Shang dynasty. It should be the drinking vessel used by the Shang royal family and a typical proto-porcelain of the Shang dynasty.

Han Era Ceramics

Many great works of pottery and ceramic art came from the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220). Lovely vessels and objects were buried with dead and have been excavated by archeologists and looters. The first use of glazes on Chinese pottery dates back to this period. Beautiful figures, particularly of animals, were created during Six Dynasties period (A.D. 220-587).

In the Han dynasty, archaic and solemn green and brown glazes were much loved. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““Pottery also played an important role in Chinese burial customs, which involved serving the deceased as if they were still alive. Using clay, craftsmen recreated scenes from life. Figurines, in the form of musicians, servants, officials, domestic animals, and buildings reflect the social conditions of ancient civilizations and the contemporary aesthetics. The surface of the pottery was often decorated with a coat of low-fired glaze. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Mature celadon was achieved in southern kilns in the A.D. first century and in the A.D. third and fourth centuries further refinements were made. Production increased but quality declined slightly. By the fourth century A.D. mature celadon has been produced at kilns in north China and many pieces of high quality were made there. According to the Shanghai Museum:“Celadon production was gradually matured during the Eastern Han and further developed during the Wei (Wu State) and the Western Jin periods. The scale of celadon production was enlarged during the periods of the Eastern Jin, the Southern dynasty and the Sui dynasty, but their quality declined slightly. From the Northern dynasty, matured celadon appeared at kilns in northern China and many masterpieces of high quality were manufactured. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

See Separate Article HAN DYNASTY ART: BRONZE MIRRORS, JADE SUITS AND TOMB FIGURES factsanddetails.com

Celadons

Celadon is a bluish, grayish green porcelain made with a slip and glaze, sometimes with incised and inlaid decorations. Evolving during the Six Dynasties period (A.D. 220-589), it is associated with both China and Korea.. The color of celadon results from natural iron oxide in the glaze, which produces the green hue when fired in a reducing atmosphere kiln.

Soyoung Lee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The term celadon is thought to derive from the name of the hero in a seventeenth-century French pastoral comedy. The color of the character Céladon’s robe evoked, in the minds of Europeans, the distinctive green-glazed ceramics from China, where celadon originated. Some scholars object to such an arbitrary and romanticized Western nomenclature. Yet the ambiguity of the term celadon effectively captures the myriad hues of greens and blues of this ceramic type. [Source: Soyoung Lee, Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003]

Some of the most beautiful porcelain ever produced was made during the Song dynasty (960-1279), when world-famous monochrome porcelains, including celadon, were produced. Ju ware, a kind of celadon from the Northern Song dynasty that ranges in color from blue to green, is the rarest of all forms of porcelain. Only 65 pieces of it exist and 23 of them are possessed by the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

See Separate Article CELADONS factsanddetails.com

Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618-906) Ceramics

Proto-porcelain evolved during the Tang dynasty. It was made by mixing clay with quartz and the mineral feldspar to make a hard, smooth-surfaced vessel. Feldspar was mixed with small amounts of iron to produce an olive-green glaze. Tang funerary vessels often contained figures of merchants. warriors, grooms, musicians and dancers. There are some works that have Hellenistic influences that came via Bactria in Afghanistan and Central Asia. Some Buddhas of immense size were produced.

In the Sui and Tang dynasties (A.D. 581-907) celadon production advanced in parallel with the production of porcelain, a vitrified ceramic material with a very hard white body. By the time of the Liao, Song and Jin dynasties (10th — 13th century) major porcelain-making kilns were widely distributed in both the south and the north. In addition to celadon and white porcelain, many other wares were popular, such as qingbai (porcelain with a bluish-white glaze), black-glazed ware, and porcelain with painted designs. A wide variety of porcelain-making techniques competed vigorously. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ During the Sui and Tang dynasties , kilns thrived in both northern and southern China. White-glazed porcelains from the Xing kilns in Hebei as well as the Ting kilns enjoyed broad popularity. Anhwei, Hunan, and Shanxi were especially known for their celadons. The Yüeh-chou region, an area surrounding present-day Lake Shang-lin in Tz'u-hsi County, Zhejiang, was the reigning center of porcelain production. Wares of the region delivered to the imperial court after the mid-Tang were characterized by a quality called "mi-se (mysterious color)".[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Potters of Six Dynasties (221-580) through the Tang dynasty (618-907) period turned their attention to the naturalistic and lively representation of modeling forms and the use of low-temperature glazes. In terms of funerary clay figures that thoroughly document the aspects of daily life at the time, they include ceremonial guards, cavalry, chariot riders, servants, vessels of daily use, and motifs of a religious nature that were either auspicious or served to dispel malignant influences. Gray ware pottery figures were sculpted in the following manner: clay was modeled into the appropriate shape, color added by applying a vitreous lead glaze, and then the piece fired at a low temperature, resulting in the final appearance. Yellow, green, and white were the most prevalent colors of glaze in this style of coloration, known as "san ts'ai", or tri-color glaze. In addition to these three more common hues, brownish-red, eggplant, sky blue, deep yellow, and other glaze colors appear in pottery pieces of the period, and they were applied to the surface using a variety of methods, including splashes, dyes, and imprinting.

See Separate Article TANG HORSES AND TANG ERA SCULPTURE AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com

Tang Horses

Chinese art specialist J.J. Lally told the New York Times, "Tang horses are the most widely popular image of Chinese art because they are immediately accessible to everyone. You don't have to read the Tang dynasty was a moment in Chinese art when there was a strong move toward realism and strong decorative impulse. Horses imported from the Near East were precious. In Tang China, the horse was the emblem of wealth and power. They are meant to embody rank and speed."

The Chinese used horses as far back as the Shang dynasty (1600 to 1100 B.C.) but these were mainly strong, draft animals. Later they began importing horses from Central Asia and Middle East. By the Tang dynasty horses were favorite subjects of not only artists but also poets and composers. The inspiration for the many of Tang horses were Tall horses, the heavenly horses from Central Asia introduced to China in the first century B.C.

The highest price ever paid for ceramics and/or a Chinese work of art was $6.1 million for a Tang dynasty horse sold by the British Rail Pension Fund to a Japanese dealer at Sotheby's in London in December 1989. Collectors like Tang horses because they can be dated with some certainty using thermoluminescnece testing.

Porcelain

Porcelain is a type of pottery made from kaolin, a fine whitish clay composed of quartz and feldspar, that becomes hard, glossy and nearly transparent when it is fired in a kiln. The word "porcelain" reportedly is derived from the Italian word porcella, meaning little pig, or possibly from a similar word meaning female pig genitals. The name was given first to a smooth, white, cowrie shell, and then to the smooth, white finish on porcelain pottery. The term “porcelain” was used in Marco Polo’s writings. Porcelain pieces can be dated by their inscribed reign marks.

"Porcelain" generally refers to an object whose body is made from clay containing kaolin, is covered with a glaze, and is fired at a high temperature so that the body material fuses and the resultant object is impervious to liquids and is resonant when struck. True porcelain is made of fine kaolin clay and feldspar, also known as petuntse or Chinese stone. It is white, thin and transparent or translucent. Before it is shaped the kaolin is mixed, filtered and vacuum pressed into slabs for aging. Blue and white porcelain has traditionally been made from kaolin clay mined near Jingdezhen, a town in southern China, and mixed with a particular kind of cobalt imported from Persia. Other kinds of porcelain include underglaze red, underglaze blue, copper red (used for imperial ceremonies), "sweet-white," peacock blue and celadon green.

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: “Porcelain, as indicated by its popular name of "china," is another major product of China. Earthenware bowls, plates, and vases have been baked from clay by almost all people since time immemorial, but porcelain is justly acclaimed as a product of Chinese genius alone. True porcelain is distinguished from ordinary pottery or earthenware by its hardness, whiteness, smoothness, translucence when made in thin pieces, nonporousness, and bell-like sound when tapped. The plates you eat from, even heavy thick ones, have these qualities and are therefore porcelain. A flower pot, on the other hand, or the brown cookie jar kept in the pantry are not porcelain but earthenware.[Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu]

See Separate Article PORCELAIN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Jingdezhen

Jingdezhen (140 kilometers northeast of, and 2½ hours by train, from Nanchang) is regarded as the "Porcelain Capital of China" and has been called the "Porcelain City" of China. The home of a centuries-old porcelain industry, it produces four famous kinds of porcelain: "blue and white," "rice pattern," "family rose" and "monochrome and polychrome glaze." Many other kinds of porcelain and porcelain sculptures are also produced here.

Jingdezhen (140 kilometers northeast of, and 2½ hours by train, from Nanchang) is regarded as the "Porcelain Capital of China" and has been called the "Porcelain City" of China. The home of a centuries-old porcelain industry, it produces four famous kinds of porcelain: "blue and white," "rice pattern," "family rose" and "monochrome and polychrome glaze." Many other kinds of porcelain and porcelain sculptures are also produced here.

Jingdezhen was known in the Song period (960–1279) for its bluish-white qingbai porcelain, which rapidly came to dominate porcelain production after it began to mass-produce underglaze blue in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). “Vase with Underglaze Blue Design of Interlaced Peonies” is a piece at the Shanghai Museum that dates to the Yuan period. According to the museum: Decorated with blue-and-white patterns all over with rich layers, this vase is an exquisite work of underglaze blue porcelain of the Yuan dynasty. The Yunjian design of the decoration band on the shoulder is almost at the same level of the band of interlaced branches and peony sprays at the belly part, highlighting two different themes. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Located on the eastern bank of the Yangtze River and bordering Anhui province to the north, Jiangdezhen is where porcelain was invented and first fired from kaolin clay mined nearby. Official kilns dedicated to the production of imperial wares were established at Jingdezhen in the early Ming period, and these kilns introduced a large number of fine wares. In the Qing period many more new wares were created, drawing on the long experience of both folk and imperial kilns. By that time Jingdezhen was famous for porcelain throughout the world.

See Separate Article JIANGDEZHEN AND ITS PORCELAIN, KILNS AND GLAZING AND PAINTING TECNIQUES factsanddetails.com

Ceramics of the Song Period

In the time of the Liao, Song and Jin dynasties (10th — 13th century) major porcelain-making kilns were widely distributed in both the south and the north. In addition to celadon and white porcelain, many other wares were popular, such as qingbai (porcelain with a bluish-white glaze), black-glazed ware, and porcelain with painted designs. A wide variety of porcelain-making techniques competed vigorously. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

According to the Shanghai Museum:“ During the Song dynasty, five well known kilns, Ru, Guan, Ge, Ding and Jun, manufactured exquisite porcelain wares for royal families. In addition, folk kilns both in the south and the north produced many unique wares of high quality. Porcelain manufacture of the Liao and Xi-Xia regimes in northern China provided many distinctive products with ethnic style and craftsmanship. Meanwhile, production of blue-white porcelain at the Jingdezhen greatly promoted its position in China. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “After the Sui and Tang dynasties, the spread of kiln firing technique allowed for porcelain to become available to both the rich and the poor. Amongst the most popular were the green wares of the Yue kilns in the South and the white wares of the Xing kilns in the North. Furthermore, Ding ware and Changsha ware were exported in large quantities, reaching as far as Egypt and Mesopotamia. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

The ruling house of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) doted on refinement and the elegant accoutrements of culture, and it accordingly gave priority to the fine arts. Under this stimulation, the manufacture of porcelain progressed, and it was at this time that several famous types of wares were produced. From the Tang dynasty (618-907) into the Sung, Ting ware succeeded Xing ware, Lung-ch'uan ware carried on the tradition of Yuah ware, and both the white wares and the green wares made great strides in terms of quality and quantity. In addition, the production of dignified shapes and harmonious glazes reached a full maturation in Kuan ware, Ju ware, Ko ware, and Chua ware. The porcelain industry at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province was also forging ahead at this time with Ying Qing wares, white wares and Tz'u-chou type wares being sold throughout the north. Pieces with black ground and white decoration or white ground and black decoration are particularly lively and exuberant, expressing the special spirit of the people. Among the black-glazed wares, Chien wares from Fujian province and Chi-chou wares from Jiangxi province are the most famous. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

See Separate Article: SONG DYNASTY CERAMICS — PORCELAIN, JU WARE AND CELADON — AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Yuan Ceramics and Porcelain

With the invention of underglaze blue porcelain in the Yuan period (1271-1368), Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province made itself the pre-eminent center for porcelain production, a position it held throughout the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. Celadon and white porcelain were superseded by porcelain with decoration painted under or over the glaze and by various wares with monochrome glazes. Porcelain decoration became richer and more colorful than ever before. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: In the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) Jingdezhen became the center of porcelain production for the entire empire. Most representative of Yuan dynasty porcelain are the underglaze blue and underglaze red wares, whose designs painted beneath the glaze in cobalt blue or copper red, replaced the more sedate monochromes of the Song Dynasty. At the same time, from the standpoint of the shape of the objects, Yuan dynasty porcelains became thick, heavy, and characterized by great size, transforming the refinement of Song Dynasty shapes. From this we can get some idea of the differences between the eating and drinking customs of the Sung and Yuan dynasties. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

During the Song, Jin and Yuan dynasties from the tenth to fourteenth centuries, the firing of stoneware are widespread. Famous stonewares were named after the locations at which they were produced. Various kilns in different places came to establish their own independent styles as each excelled in the forms, glazes, skills for decorating and techniques of production for which they became known.

See Separate Articles YUAN DYNASTY CRAFTS AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com

Ming and Qing Ceramics and Porcelain

Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) ceramics were known for the boldness of their form and decoration and the varieties of design. Craftsmen made both huge and highly decorated vessels and small, delicate, white ones. Many of the wonderful decorations and glazes — peach bloom, moonlight blue, cracked ice, and ox blood glazes; and rice grain, rose pink and black decorations — were inspired by nature. In 1402, the Ming Emperor Jianwen ordered the establishment of an imperial porcelain factory in Jingdezhen. It's sole function was to produce porcelain for court use in state and religious ceremonies and for tableware and gifts.

Between 1350 and 1750 Jiangdezhen was the production center for nearly all of the world's porcelain. Jiangdezhen was located near abundant supplies of kaolin, the clay used in porcelain making, and fuel needed to fire up kilns. It also had access to China's coast, which was used for transporting finished products to places in China and around the world. So much porcelain was made that Jingdezhen now sits on a foundation of shards from discarded pottery that over is four meters deep in places.

Qing dynasty (1644-1912) porcelain was famous for its polychrome decorations, delicately painted landscapes, and bird and flower and multicolored enamel designs. Many of the subject had symbolic meanings. The work of craftsmen reached a high point during the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722) During a rebellion in 1853, the imperial factory was burned. Rebels sacked the town and killed some potters. The factory was rebuilt in 1864 but never regained its former stature. With the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912, the long history of Chinese porcelain making drew to a close.

See Separate Article MING DYNASTY PORCELAIN factsanddetails.com

Some of the "Eighteen Scholars"

Tea Pots and Wine Vessels in the Painting "The Eighteen Scholars"

"The Eighteen Scholars" by an anonymous Ming dynasty artist, is a hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, measuring 173.7 x 102.9 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The white porcelain handled pot has a flaring mouth, constricted neck, and sloping shoulders, both sides of which have an apricot-leaf form standing out from the surface. Its slender spout is as tall as the opening, and the vessel has a reticulated flat handle. This type of flat pot probably dates from the last half of the sixteenth or first half of the seventeenth century. Accompanying it is a cup in the shape of an inverted bell, its flaring rim, deep body, and short base reflecting a form popular during the Xuande reign (1426-1435). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“This gem-inlaid golden handled pot is part of a wine vessel set. The cover of this melon-shaped pot is rendered in two levels and topped with a semi-precious stone knob. The spout, handle, and body are also inlaid with turquoise and semi-precious stones, the shape quite complex and ingeniously designed. In front is a large wine-warming bowl inlaid with gems in continuous bead and floral patterning, accompanied by a small golden cup and tray. The cup has a flaring rim, raised foot, and plain body with two "ruyi"-shaped" handles welded onto the sides, the rim featuring a continuous bead design. The use of precious inlays on gold and silver vessels was popular in the middle and late Ming dynasty, this set featuring gorgeous decoration much in the manner of the imperial court.

“The floral-stem peach-shaped white jade cup is named after its floral-stem handle. Its tray here is in the form of a curving lotus leaf, the inside of which is decorated with shallow vein engraving and the center raised to serve as a cup stand. Jade peach-shaped cups appeared in the Southern Song period and became especially numerous later in the Ming dynasty. In the middle and late Ming, under the influence of Taoism, such vessels shaped like a peach (symbolizing immortality) became extremely popular due to their auspicious overtones of longevity. Generally speaking, Ming jade peach-shaped cups have more realistic stems, and few examples have a tray, with fewer still rendered in the shape of a lotus leaf.

“The body of the white porcelain vessel depicted here is decorated with a red heavenly horse among waves, similar to the flying horse and auspicious clouds often seen on porcelains after the Chenghua (1465-1487) and during the Jiajing era (1522-1566). Although only a portion of the decoration is revealed, the coarse lines of the horse's hair along with the patterned flame and cloud forms accord with imperial wares of the Jiajing court, evidence of a decline in precision painting at the time.

Image Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, McClung Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021