MING DYNASTY PORCELAIN

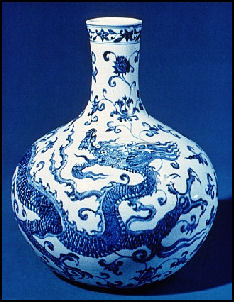

Ming Dynasty ceramics were known for the boldness of their form and decoration and the varieties of design. Craftsmen made both huge and highly decorated vessels and small, delicate, white ones. Many of the wonderful decorations and glazes — peach bloom, moonlight blue, cracked ice, and ox blood glazes; and rice grain, rose pink and black decorations — were inspired by nature.

Ming Dynasty ceramics were known for the boldness of their form and decoration and the varieties of design. Craftsmen made both huge and highly decorated vessels and small, delicate, white ones. Many of the wonderful decorations and glazes — peach bloom, moonlight blue, cracked ice, and ox blood glazes; and rice grain, rose pink and black decorations — were inspired by nature.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “With the establishment of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) in the latter half of the 14th century, the production of objets d'art entered a new realm. The craft most heavily endorsed by the Ming court was the making of porcelains. Painted and colored glazes of decorative designs became more elaborate, this period may well be dubbed a "new era of ornamentation." Compared with plainer Song and Yuan pieces, the emphasis on colors in Ming porcelains is a key feature differentiating them from predecessors. The administration of porcelain production was very strict, with specially appointed officials supervising its operation and introducing innovative approaches. Advancing from the high- and low-temperature, monochrome, underglaze-blue (blue-and-white), and underglaze-red wares of the late Yuan, they were able to come up with multi-colored, "wu-ts'ai (five-color)", and "tou-ts'ai (competing-color)" wares, ushering in a new, lively, and colorful period of decorative design. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Following Cheng Ho's maritime explorations in the early Ming, China's contact with the Middle East became more frequent. There were members of the court who were followers of Tibetan Buddhism and Islam, and they eagerly absorbed elements of Persian culture. In the design of shapes and decorative motifs, auspicious Arabic and Tibetan inscriptions were integrated into the making of wares. One can see the introduction of new elements, increasing the vitality and beauty of Ming craftsmanship.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In the Ming epoch the porcelain with blue decoration on a white ground became general; the first examples, from the famous kilns in Ching-te-chen, in the province of Jiangxi, were relatively coarse, but in the fifteenth century the production was much finer. In the sixteenth century the quality deteriorated, owing to the disuse of the cobalt from the Middle East (perhaps from Persia) in favour of Sumatra cobalt, which did not yield the same brilliant colour. In the Ming epoch there also appeared the first brilliant red colour, a product of iron, and a start was then made with three-colour porcelain (with lead glaze) or five-colour (enamel). The many porcelains exported to western Asia and Europe first influenced European ceramics (Delft), and then were imitated in Europe (Böttger); the early European porcelains long showed Chinese influence (the so-called onion pattern, blue on a white ground). In addition to the porcelain of the Ming epoch, of which the finest specimens are in the palace at Istanbul, especially famous are the lacquers (carved lacquer, lacquer painting, gold lacquer) of the Ming epoch and the cloisonné work of the same period. These are closely associated with the contemporary work in Japan. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

See Separate Articles: CHINESE CERAMICS factsanddetails.com ; PORCELAIN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CELADONS factsanddetails.com ; JIANGDEZHEN AND ITS PORCELAIN, KILNS AND GLAZING AND PAINTING TECNIQUES factsanddetails.com

Ceramics and Porcelain: 1) China Museums Online: chinaonlinemuseum.com ; 2) Guide to Chinese Ceramics: Song Dynasty, Minneapolis Institute of Arts; artsmia.org features many examples of different types of ceramic ware produced during the Song dynasty, including ding, qingbai, longquan, jun, guan and cizhou. 3) Making a Cizhou Vessel Princeton University Art Museum artmuseum.princeton.edu. This interactive site shows users seven steps used to create Song- and Yuan-era Cizhou vessels.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “In Pursuit of the Dragon: Traditions and Transitions in Ming Ceramics” by Idemitsu Bijutsukan. Amazon.com; “Objectifying China: Ming and Qing Dynasty Ceramics and Their Stylistic Influences Abroad” by Ben Chiesa, Florian Knothe, et al. Amazon.com; “The Wares of the Ming Dynasty” by R. L. Hobson Amazon.com; “A Treasury of Ming and Qing Dynasty Palace Furniture from The Palace Museum Collection” (2 Volumes) by Desheng Hu and Curtis Evarts Amazon.com; “Power and Glory: Court Arts of China's Ming Dynasty” by He Li, Michael Knight, et al. Amazon.com; “Defining Yongle: Imperial Art in Early Fifteenth-Century China” by James C. Y. Watt and Denise Patry Leidy Amazon.com; Ceramics: “Chinese Ceramics: From the Paleolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty” by Laurie Barnes, Pengbo Ding, Jixian Li, Kuishan Quan Amazon.com “How to Read Chinese Ceramics by Denise Patry Leidy (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Amazon.com; “Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry, and Recreation” by Nigel Wood Amazon.com; Celadons: “Chinese Celadon Wares”by Godfrey St. George Montague. Gompertz Amazon.com “Ice and Green Clouds: Traditions of Chinese Celadon” by Yutaka Mino and Katherine Tsiang Amazon.com; Porcelain: “Illustrated Brief History of Chinese Porcelain” by Guimei Yang and Hardie Alison Amazon.com “Chinese Porcelain” by Anthony du Boulay Amazon.com; “Chinese Pottery and Porcelain” By Vainker ( Amazon.com ; Jingdezhen: “China's Porcelain Capital: The Rise, Fall and Reinvention of Ceramics in Jingdezhen” by Maris Boyd Gillette Amazon.com; “Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum” by Zhu Pei Amazon.com; Art: “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Ming Dynasty Government-Run Kilns

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The imperial porcelain factory was established at Jingdezhen at the beginning of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), and from this time the position of Jingdezhen as the center of porcelain production became consolidated. The imperial wares that were specially manufactured for use at court were made particularly exquisitely and were marked with the reign mark of the emperor himself. In addition to the monochromes and the underglaze blue porcelains that continued to be produced among the official wares of the Ming dynasty, innovations appeared throughout the period, such as pan-t'o-t'ai wares in the Yung-lo reign (1403-1425), chi-hung in the Hsuan-te (1426-1436), tou-ts'ai in the Ch'eng-hua (1465-1488), chiao-huang in the Hung-chih (1488-1506), and wu-ts'ai in the Wan-li (1573-1620), all of which are representatively significant in the history of the development of Ming dynasty porcelain. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Ceramic production was an important state affair in the Ming dynasty. In early Ming, the ceramics industry was mainly based at the Longquan kilns in Zhejiang province and the Jingdezheng kilns in Jiangxi province. Their products not only circulated all over China but also reached overseas markets. Furthermore, both of these kiln sites produced official wares.

“In early Ming, the imperial kilns were set up at Jingdezhen, establishing the fundamental institution and system of Jingdezhen official wares for the next five hundred years. Production of official wares at the time was under direct supervision of the central government, which provided models and designs while also appointing superintendents. Under constant supervision, the quality and quantity of the products were carefully controlled. The selected final products were sent directly to the court for use by the imperial family and officials. From the Yongle reign, official wares began to bear the emperors’ reign mark, becoming the standard practice for most later official wares.

“Apart from Jingdezhen imperial kilns, other civilian kilns also produced porcelains. However, in terms of the quality and quantity of products, kiln types, modes of operation, and styles of their works, huge differences existed between official and civilian kilns. In late Ming, political and economic changes as diverse values merged. Although the official kilns possessed superior raw materials, its management was slack and lacking order in technique. Civilian kilns, on the other hand, took advantage of the occasion and flourished.

Jingdezhen

In 1402, the Ming Emperor Jianwen ordered the establishment of an imperial porcelain factory in Jingdezhen. It's sole function was to produce porcelain for court use in state and religious ceremonies and for tableware and gifts. Between 1350 and 1750 Jiangdezhen was the production center for nearly all of the world's porcelain. Jiangdezhen was located near abundant supplies of kaolin, the clay used in porcelain making, and fuel needed to fire up kilns. It also had access to China's coast, which was used for transporting finished products to places in China and around the world. So much porcelain was made that Jingdezhen now sits on a foundation of shards from discarded pottery that over is four meters deep in places.

Modern Jiangdezhen (140 kilometers northeast of, and 2½ hours by train, from Nanchang) is regarded as the "Porcelain Capital of China" and has been called the "Porcelain City" of China. The home of a centuries-old porcelain industry, it produces four famous kinds of porcelain: "blue and white," "rice pattern," "family rose" and "monochrome and polychrome glaze." Many other kinds of porcelain and porcelain sculptures are also produced here.

Jingdezhen was known in the Song period (960–1279) for its bluish-white qingbai porcelain, which rapidly came to dominate porcelain production after it began to mass-produce underglaze blue in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). “Vase with Underglaze Blue Design of Interlaced Peonies” is a piece at the Shanghai Museum that dates to the Yuan period. According to the museum: Decorated with blue-and-white patterns all over with rich layers, this vase is an exquisite work of underglaze blue porcelain of the Yuan dynasty. The Yunjian design of the decoration band on the shoulder is almost at the same level of the band of interlaced branches and peony sprays at the belly part, highlighting two different themes. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Located on the eastern bank of the Yangtze River and bordering Anhui province to the north, Jiangdezhen is where porcelain was invented and first fired from kaolin clay mined nearby. Official kilns dedicated to the production of imperial wares were established at Jingdezhen in the early Ming period, and these kilns introduced a large number of fine wares. In the Qing period many more new wares were created, drawing on the long experience of both folk and imperial kilns. By that time Jingdezhen was famous for porcelain throughout the world.

See Separate Article JIANGDEZHEN AND ITS PORCELAIN, KILNS AND GLAZING AND PAINTING TECNIQUES factsanddetails.com

Underglaze Wares

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Underglaze blue and underglaze red are wares had their beginnings in the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) and were major products of the Jingdezhen kilns. These wares were made by first sketching cobalt blue or copper red on the molded clay, over which a transparent glaze was applied and then fired at a high temperature. Besides monochrome red and white glazed ceramics, the most common imperial wares of the Hongwu (1368-1398) era in the early Ming were underglaze blue and underglaze red. Their styles still retain those of the Yuan dynasty and are often large in size. Following the Hongwu period came the Yung-lo (1403-1424) and Hsüan-te (1426-1435) reigns, the golden age for underglaze blue wares. In terms of shape, glaze, and decorative design, works of this era are superior to those from the late Yuan and early Ming in their beauty, spirit, and liveliness. Some examples of this are: 1) Bowl with underglaze copper red decoration of peony scrolls from the Ming dynasty, Hongwu reign (1368-98) and 2) a Single-handled cup and saucer with cobalt blue glaze, Jingdezhen ware from the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368).

[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Underglaze blue and underglaze red are wares had their beginnings in the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) and were major products of the Jingdezhen kilns. These wares were made by first sketching cobalt blue or copper red on the molded clay, over which a transparent glaze was applied and then fired at a high temperature. Besides monochrome red and white glazed ceramics, the most common imperial wares of the Hongwu (1368-1398) era in the early Ming were underglaze blue and underglaze red. Their styles still retain those of the Yuan dynasty and are often large in size. Following the Hongwu period came the Yung-lo (1403-1424) and Hsüan-te (1426-1435) reigns, the golden age for underglaze blue wares. In terms of shape, glaze, and decorative design, works of this era are superior to those from the late Yuan and early Ming in their beauty, spirit, and liveliness. Some examples of this are: 1) Bowl with underglaze copper red decoration of peony scrolls from the Ming dynasty, Hongwu reign (1368-98) and 2) a Single-handled cup and saucer with cobalt blue glaze, Jingdezhen ware from the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368).

[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The production of underglaze blue wares in the Ming dynasty, after passing through an initial phase in the Hongwu reign and reaching a golden age in the Yung-lo and Hsüan-te reigns, was further refined during the Ch'eng-hua (1465-1487) era. On the whole, underglaze blue became the primary product of Jingdezhen kilns. On white porcelain are clear glaze and intricate designs, and the underglaze blue of each reign features different materials as well as varying shades and intensities of colors. With delicate and clever drawings as well as realistic and abstract expressions of artistry, the porcelain of each reign may very well be considered a paragon of underglaze ware in its own right. Under the transparent glaze, these underglaze blue pieces, regardless of their shapes or decorations, were highly innovative, and many of them, such as the Yung-lo and Hsüan-te celestial globular vase, covered jar, large stem bowl, small stem cup, and stem cup have become archetypes in the field of Chinese ceramics. Such designs as the dragon-and-phoenix motif, poetic imagery, Eight Buddhist emblems among lotus flowers, and portrayals of children at play all became models for later imitations by artisans at the imperial kilns

"During the middle Ming dynasty, the underglaze blue of the Ch'eng-hua and Hung-chih reigns (from 1488 to 1505) was made with cobalt from Lo-p'ing in Jiangxi Province, which was called "p'ing-teng " or "p'o-Tang" blue. The colors are lighter and more delicate, with a grayish tinge to the blue and very appealing to the eye. The clear and bright underglaze blue of the Cheng-te reign (1506-1521) was, on the other hand, made with cobalt from Jui-chou in Jiangxi Province, known as "shih-tzu" blue. It has grayer overtones, and its decorations are drawn with large, free strokes. With the Cheng-te Emperor's belief in Islam, imperial wares often carried Arabic inscriptions, thereby adding an exotic foreign element to them. Examples of this include: 1) Large bowl with underglaze blue decoration of lotus pond from the Ming dynasty, Cheng-te reign (1506-1521) and 2) a Tea cup with underglaze blue decoration of lotus pond from the Ming dynasty, Ch'eng-hua reign (1465-1487)

Color Glazes and Overglaze Colors in Ming Porcelain

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Many color glazes and overglaze colors have their origins in the Yuan dynasty, but they only became common during the early part of the Ming. Hongwu red glaze, Yung-lo sweet white, Hsüan-te ruby red, underglaze copper red, as well as green, red, yellow, violet, and peacock green overglazes gave a new appearance to Ming imperial wares and provided the foundation for the later growth of "wu-ts'ai (five-color)" and "tou-ts'ai (competing-color)" wares. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Underglaze blue wares, along with the integration of monochrome, dual-color, and even tri-color overglazes, allow for a better understanding of the development behind the new genres of "wu-ts'ai " and "tou-ts'ai". Underglaze blue and overglaze colors generated striking contrasts, delivering the Ming imperial workshops into a new era of ornamentation.

Examples of this include 1) Wine cup with decoration of chicken in a garden outlined in underglaze blue and filled in with tou-ts'ai colors, Ming dynasty, Ch'eng-hua reign (1465-1487); 2) Tea cup with decoration of grape vines outlined in underglaze blue and filled in with tou-ts'ai colors, Ming dynasty, Ch'eng-hua reign (1465-1487); 3) Stemcup with underglaze copper red decoration of three fruits, Ming dynasty, Hsüan-te reign (1426-1435); and 4) Sauce pots with cobalt blue and sacrificial red glazed with incised decoration of lotus petals, Ming dynasty, Hsüan-te reign (1426-1435).

Porcelains with Persian Shapes and Tibetan Scripts

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “During the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), as part of the Mongol empire, the Jingdezhen kilns in China produced a large quantity of underglaze blue porcelains, fusing imperial styles with a Near Eastern flair in response to the needs of Muslims. At the beginning of the Ming dynasty, the Yung-lo Emperor ordered Cheng Ho to explore the western seas in order to expand ties with other lands, reaching the Islamic world among others. Porcelain thus became an important item of exchange and trade. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The shapes and decorative designs on porcelains during the Yung-lo and Hsüan-te reigns often exhibit a Near Eastern style. In the collection of the National Palace Museum, many of the underglaze blue ceramics from this period feature shapes and designs influenced by Islamic metalwork, reflecting the customs of that time. Among the examples of this are: 1) Flask with underglaze blue decoration of musicians in a landscape from the Ming dynasty, Yung-lo reign (1403-1424), and 2) a Perfume vessel with underglaze blue decoration of flowers in openwork, from the Ming dynasty, Yung-Io reign (1403-1424)

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “After the decline of the Yuan dynasty, contact between China and Tibet still remained close, the Ming government valuing and strengthening its ties with the area. The Yung-lo and Hsüan-te reigns saw the appointment of leaders from the three major Buddhist sects as "fa-wang (doctrinal kings)", an attempt at reinforcing China 's influence in Tibet. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The Yung-lo and Hsüan-te Emperors were also devout followers of Tibetan Buddhism. To meet the requirements for gifts and ritual vessels, the imperial Jingdezhen kilns produced porcelains with auspicious Tibetan inscriptions, as well as ceramics in the form of Tibetan religious implements. This reflected not only the special position of Tibetan Buddhism at the Ming imperial court, but also revealed the significance of these Tibetan-bearing porcelains, for they were also delivered as gifts. Fine examples of this include the “Monk's cap ewer with underglaze blue decoration of dragons among lotus blossoms and Tibetan script from the Ming dynasty, Hsüan-te reign (1426-1435)

Ming and Qing Vases and Flowers

You tend to thin of Ming and Qing vases as stand-alone objects but in Imperial China they were used to display flowers. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ Flower vessels include planters, in which flowers and plants are grown, along with vases and other objects used to hold floral arrangements. In China, they were traditionally made from a wide range of materials, such as bronze, ceramic, jade, stone, glass, lacquer, wood and bamboo. They also come in diverse forms, including standing and hanging vases, planters, bowls, dishes, tubs, and baskets. The most well-know ones are made of porcelain. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Flower arrangement in the Ming and Qing dynasties mostly used vases which often included metal inner liners. When water freezes in winter and early spring, the liners serve to keep the water away from the vase and thus prevent cracking. The liner caps often have holes or openwork which provide support for the stems and branches of the arrangement. The archives of the imperial household workshops during the Yongzheng reign in the Qing dynasty mention a "lotus pod inner liner" with a round cap and holes as well as a "crackle-style inner lining" decorated with a continuous bat and dragon design. From actual vases and their depictions in paintings, we can observe the choices of vases and the way they were used in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Converted ancient bronze and jade objects, enameled flower vessels, and imitation ding, ru, guan and ge porcelains all allow us to appreciate the elegance and innovation in imperial life during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

“"Floral arrangements" are displays of cut flowers and branches placed in vases to appreciate their aesthetic beauty. The way the flowers and the vase are selected often depends on the size and function of the display space-" Hall flowers", for example, are reserved for large hall areas and typically feature conspicuous vessels with a rich variety of beautiful flowers-" Studio flowers" on the other hand are for more private spaces and usually smaller and more refined. Flower arrangements also require attention to how the branches and stems will be fixed in place; this is why many vases in the museum collection feature metal inner liners with holes or have multiple necks.

“Potted scenery and flower arrangements can appear alone, in groups, or can incorporate decorative pieces in combination with other materials. Homonyms in Chinese for the floral material, flower holder, and decorative pieces create horticultural blessings with auspicious meanings, such as "Jade halls of wealth and nobility" or "May all go as you wish;" this gives insight into the historical meaning and conception of the art. The Ming and Qing imperial courts mostly used contemporary porcelain and enameled vessels but sometimes they also adapted selected bronze, jade, and ceramic antiques for this purpose. Changing the original function, these antiquities became floral vessels combining an archaic as well as elegantly opulent taste in art.

Ming and Qing Planters

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““"Planters" are vessels for growing the whole plant. Aesthetically arranged within, the plant turns the vessel into a kind of living art. Planters have been likened to landscapes in miniature, forming a microcosm where plants and rocks serve as a setting for figures and other creatures. These small garden views of macroscopic scenery are objects for appreciation, contemplation, and even vicarious travel, being thereby imbued with considerable meaning. The planters themselves are usually thick and heavy, typically shallow basins with wide rims in a variety of shapes, such as round, rectangular, square, and polygonal. They are also frequently accompanied by trays or in the form of various animals. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The porcelain planters from the Ming dynasty in the collection of National Palace Museum mostly feature underglaze-blue, polychrome wucai, and monochrome glazes. Jun porcelain planters with running splotches of reddish-purple can also often be seen in Ming paintings. Planters and trays form sets with arrangements of calamus grown around rocks in what is known as a "calamus rock planter-" Jun planters were often engraved with the names of halls at the Qing court, indicating their function as decorative pieces in their respective palaces.

The underglaze-blue and wucai planters fired at the Jingdezhen kilns in the early Qing reveal superior colors glazes and marvelous bird-and-flower and landscape rendering that appear just like paintings. Empress Dowager Cixi particularly appreciated flower vessels, and those with her marks "Daya Zhai”and “Tihe Dian zhi" often stand out for their unique illustrations of idyllic garden floral scenes and auspicious motifs. Large numbers of flower vessels fired in private kilns also made their way to the court during the late Qing dynasty. In addition to popular auspicious and celebratory themes, a confluence of figural and bird-and-flower subjects as well as styles associated with painting schools emerged at this time.

Chinese Porcelain Exported to Europe

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: In the A.D. second millennium, the southern sea route to China rose to a position of commanding importance. Over it porcelain became by all odds the major export shipped from China to the outside world. Tremendous quantities of porcelain went to Southeast Asia, including the Philippines, Indo-China, Siam, Malaya, the East Indies, Ceylon, and adjoining regions. Much porcelain went even farther, crossing the Indian Ocean and passing up the Persian Gulf to reach Persia, Syria, and Egypt. Some of it, too, went as far as the southeast coast of Africa, where its presence has been used by modern archaeologists as a means for dating certain recently discovered sites of Negro cultures. [Source: Derk Bodde, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University]

“From the fifteenth century on porcelain appeared in Europe in steadily increasing quantities. In the sixteenth century attempts, only partially successful, were made in Italy to imitate the marvelous product. Our word, porcelain, which comes from the Italian porcellana, is a memory of these attempts. This word originally referred in Italian to a small kind of white conch shell, from which porcelain was at first believed to be made.

Jeffrey Munger and Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Introduced to Europe in the fourteenth century, Chinese porcelains were regarded as objects of great rarity and luxury. The examples that appeared in Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were often mounted in gilt silver, which emphasized their preciousness and transformed them into entirely different objects. By the early sixteenth century—after Portugal established trade routes to the Far East and began commercial trade with Asia—Chinese potters began to produce objects specifically for export to the West and porcelains began to arrive in some quantity. An unusually early example of export porcelain is a ewer decorated with the royal arms of Portugal; the arms are painted upside down, however—a reflection of the unfamiliarity of the Chinese with the symbols and customs of their new trading partner. [Source: Jeffrey Munger, Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Department of American Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art[Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Porcelains were only a small part of the trade—the cargoes were full of tea, silks, paintings, lacquerware, metalwork, and ivory. The porcelains were often stored at the lowest level of the ships, both to provide ballast and because they were impervious to water, in contrast to the even more expensive tea stored above. The blue-and-white dishes that comprised such a significant proportion of the export porcelain trade became known as kraak porcelain, the term deriving from the Dutch name for caracca, the Portuguese merchant ship. Characteristic features of kraak dishes were decoration divided into panels on the wide border, and a central scene depicting a stylized landscape.\^/

“As the export trade increased, so did the demand from Europe for familiar, utilitarian forms. European forms such as mugs, ewers, tazze, and candlesticks were unknown in China, so models were sent to the Chinese potteries to be copied. While silver forms probably served as the original source for many of the forms that were reproduced in porcelain, it is now thought that wooden models were provided to the Chinese potters. It is likely that just such a model inspired a porcelain taperstick of around 1700–1710.\^/

“Porcelain decorated only in blue pigment painted under the glaze dominated the export trade until the very end of the seventeenth century. The popularity of polychrome enameled decoration, painted over the glaze seems to be a result of the growing interest in porcelain decorated with coats of arms. The first armorial porcelain was painted in cobalt blue only, and this monochrome palette made it extremely difficult to depict a legible coat of arms. Polychrome enamels allowed for detailed, accurate coats of arms, and the trade in armorial porcelain became the defining aspect of Chinese export porcelain in the eighteenth century. Curiously, only one complete design for an armorial service survives; made for Leake Okeover of England, the service dates to about 1740.\^/

Ming Porcelain Exports

From the beginning production at the Ming porcelain factories in Jingdezhen were oriented towards the export market. The factories produced coffee cups and beer mugs centuries before these drinks became popular in China. They also produced plates with Arabic and Persian motifs and place setting emblazoned with European coats of arms.

The porcelain trade was so lucrative that the porcelain making processes were closely guarded secrets and Jingdezhen was officially off limits to visitors to keep spies from uncovering these secrets. Over three million pieces were exported to Europe between 1604 and 1657 alone. This was around that the same time that the word "china" began being used in England to describe porcelains because the two were so closely associated with each other.

Pere d’Entrecolles, a Jesuit missionary from France, secretly entered Jingdezhen and described porcelain making in the city in letters that made their way to Europe in the early 1700s. He described a city with a million people and 3,000 kilns that were fired up day and night and filled the night sky with an orange glow. He learned the process but confused the clays.

Around he same time that d’Entrecolles was describing porcelain-making in Jingdezhen, Germans working independently in their homeland discovered the secret to making porcelain Large scale porcelain production began in the West in 1710 in Meissen, Germany.

Chinese porcelain dominated the world until European manufacturers such as those in Messen, Germany and Wedgewood, England began producing products of equal quality but at a cheaper price. After that the Chinese porcelain industry collapsed as many industries have done today when underpriced by cheap Chinese imports.

Porcelain Production in Europe

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: “It was only in 1709, however, that true hard porcelain was successfully produced in Europe, and this through a curious accident. For nine years before that date a German artisan, named Frederick Böttger, had been trying to make porcelain. His patron was Augustus the Strong of Saxony, and he worked at Meissen, a few miles outside of Dresden, which was later to become famous for its "chinaware." This was the period in Europe when most people wore wigs which were whitened with a powder. In 1709 Böttger happened to notice that the hair powder he was using was peculiarly heavy. Investigating the reason for this heaviness, he discovered that it was caused by the presence of kaolin. From this kaolin he succeeded in producing the first hard porcelain ever made in Europe. [Source: Derk Bodde, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University]

“A porcelain works was straightway established at Meissen by Böttger's patron, Augustus. He became so enthusiastic over the new discovery that he wished it to be used even for the making of chairs and tables. As in the case of many other new inventions, the process was at first a jealously guarded secret. The artisans were sworn to absolute secrecy and operated their kilns behind high walls, where they lived as virtual prisoners. In 1718, however, one of them made his escape to Vienna, where he brought the precious secret. The following decades saw the rapid erection of porcelain works in France, Holland, England, and other countries.

“Thus European porcelain came as an independent invention — an invention, nevertheless, directly inspired by examples of Chinese porcelain, which had been closely studied by Böttger during his years of experimentation. Most of the eighteenth century products of European kilns, moreover, closely imitated Chinese wares in their techniques, shape, color, and design. Especially is this true of the famous blue-and-white ware of Delft, Holland. The early examples of delftware often amazingly resemble the "willow pattern" and other designs commonly found on Chinese porcelain. Despite the enormous amount of porcelain since produced in Europe and elsewhere, however, the best work of the Chinese potter has never been successfully equaled outside the land of its origin.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “With the appearance of porcelain factories in Europe in the early eighteenth century, the demand for Chinese export porcelain began to diminish, and by the second half of the century the trade was in serious decline. New geographical markets, however, revitalized the export porcelain industry. Following the nation's newfound independence in 1784, America officially entered into trade with China. Consistent with European trade, American agents in China expedited special orders for clients. By the late nineteenth century, Chinese export porcelains, especially blue-and-white ware, had achieved a status in this country above the merely utilitarian. Looked upon with nostalgia, they became emblematic of the colonial era. During the last decades of the century, Chinese export porcelains were increasingly collected by connoisseurs, an indication of a new antiquarian interest in America's past.[Source: Jeffrey Munger, Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Department of American Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art[Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org]

Ming Dynasty "Chicken Cup" Sell for $36.3 Million

In 2014 a Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) "Chicken Cup" sold for for $36 million. James Pomfret of Reuters wrote: “A rare wine cup fired in the imperial kilns of China's Ming dynasty more than 500 years ago sold for HK$281.2 million (US$36,3 million) at a Sotheby's sale in Hong Kong, making it one of the most expensive Chinese cultural relics ever auctioned. The tiny porcelain cup from the Chenghua period, dating from 1465 to 1487, is painted with cocks, hens and chicks, and known simply as a 'chicken cup'. It is considered one of the most sought-after items in Chinese art, viewed with a reverence perhaps equivalent to that for the jewelled Faberge eggs of Tsarist Russia. "Every time a chicken cup comes up on the market, it totally redefines prices in the field of Chinese art," said Nicolas Chow, deputy chairman of Sotheby's Asia, after the sale. The last time a similar chicken cup was auctioned, in 1999, it fetched HK$29 million, around a tenth of the 2014 price.[Source: James Pomfret, Reuters, April 8, 2014]

“With just 16 known Chenghua chicken cups surviving to the present day, most in public museums, only a handful have ever come to auction. Only four of these remain in private hands. Prized by Chinese emperors and afficionados through the centuries for their quality, rarity and legendary silky texture, Chenghua chicken cups fired in the imperial kilns of Jingdezhen are among the most prized, and forged, objects in Chinese art.

“In a packed auction hall, bidding for the delicate, palm-sized cup began at HK$160 million and drew steady bids from three parties, before being eventually sold to major Chinese collector Liu Yiqian for a bid of HK$250 million. The final price of HK$281.2 million, including fees, was a new world auction record for any Chinese porcelain.

“The cup had come from the celebrated Western collection of Chinese ceramics, the 'Meiyintang', accumulated over half a century by Swiss pharmaceutical tycoons the Zuellig brothers. With the purchase by Liu, a Shanghai-based billionaire with his own private 'Long Museum', the Meiyintang centrepiece is expected to become the only known genuine chicken cup in China. “"The price was OK, not so high, not so low," said Robert Chang, a leading collector based in Hong Kong. Some experts said China's slowing economy and credit squeeze may have sapped some market enthusiasm for the chicken cup, with the price falling just short of its high estimate. "There were not as many bidders, which was kind of surprising," said Richard Littleton, a Western dealer at the sale. "Where is all this big Chinese money we were expecting to see?"

Liu Yiqian paid for the cup with an American Express card and then proceeded to shock everyone by celebrating his new purchase by sipping some tea from it. The Wall Street Journal reported: “Mr. Liu bought his cup in a heated Hong Kong Sotheby’s bidding war that lasted seven minutes. When he paid up — by swiping his American Express card an individual 24 times, according to Sotheby’s — he also decided to take a celebratory swig from the cup. Images of Mr. Liu sipping from the cup circulated over the Internet this weekend, sparking fast condemnation from Chinese observers online.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei ; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021