MING DYNASTY ART

Ming Era Toothpick Box

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The early Ming dynasty was a period of cultural restoration and expansion. “Early Ming decorative arts inherited the richly eclectic legacy of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, which included both regional Chinese traditions and foreign influences. For example, the fourteenth-century development of blue-and-white ware and cloisonné; enamelware arose, at least in part, in response to lively trade with the Islamic world, and many Ming examples continued to reflect strong West Asian influences. A special court-based Bureau of Design ensured that a uniform standard of decoration was established for imperial production in ceramics, textiles, metalwork, and lacquer. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “With the establishment of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) in the latter half of the 14th century, the production of objets d'art entered a new realm. In the world of porcelain alone, as painted and colored glazes of decorative designs became more elaborate, this period may well be dubbed a "new era of ornamentation." Compared with plainer Song and Yuan pieces, the emphasis on colors in Ming porcelains is a key feature differentiating them from predecessors. Be it early Ming piece of carved red lacquer with its multi-layered engraving or a glittering work of cloisonné enamel, one can clearly observe the value that Ming artists placed on color. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Items of daily use were specially produced for the Ming imperial court. The most skilled craftsmen of ceramics, lacquers, enamels, and textiles were summoned to work at the imperial workshops. Court officials also studied the arts themselves, and even they themselves provided exemplary models. With the full support of official supplies of materials, manpower, and tools, the development of imperial wares reached new heights. The handicraft most heavily endorsed by the Ming court was the making of porcelains.

“Following Zheng Ho's maritime explorations in the early Ming, China's contact with the Middle East became more frequent. There were members of the court who were followers of Tibetan Buddhism and Islam, and they eagerly absorbed elements of Persian culture. In the design of shapes and decorative motifs, auspicious Arabic and Tibetan inscriptions were integrated into the making of wares. One can see the introduction of new elements, increasing the vitality and beauty of Ming craftsmanship.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “Just as puppet plays and shadow theatre are the "opera of the common man" and took a new development in Ming time, the wood-cut and block-printing developed largely as a cheap substitute of real paintings. The new urbanites wanted to have paintings of the masters and found in the wood-cut which soon became a multi-colour print a cheap mass medium. Block printing in colours, developed in the Yangtze valley, was adopted by Japan and found its highest refinement there. But the Ming are also famous for their monumental architecture which largely followed Mongol patterns. Among the most famous examples is the famous Great Wall which had been in dilapidation and was rebuilt; the great city walls of Beijing; and large parts of the palaces of Beijing, begun in the Mongol epoch. It was at this time that the official style which we may observe to this day in North China was developed, the style employed everywhere, until in the age of concrete it lost its justification. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Website on the Ming Dynasty Ming Studies mingstudies.arts.ubc.ca; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MING- AND QING-ERA CHINA AND FOREIGN INTRUSIONS factsanddetails.com; HONGWU (ZHU YUANZHANG) AND OTHER MING DYNASTY EMPERORS factsanddetails.com; YONGLE EMPEROR factsanddetails.com; MING DYNASTY DOCUMENTS AND THEIR INSIGHTS INTO MING LIFE factsanddetails.com; EXPLORATION AND EUROPEAN INFLUENCES IN THE MING DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; QING- AND MING-ERA ECONOMY factsanddetails.com; MING-QING ECONOMY AND FOREIGN TRADE factsanddetails.com; WOKOU: JAPANESE PIRATES factsanddetails.com; CHINESE EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com; ZHENG HE: THE GREAT CHINESE EUNUCH EXPLORER factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Power and Glory: Court Arts of China's Ming Dynasty” by He Li, Michael Knight, et al. Amazon.com; “Defining Yongle: Imperial Art in Early Fifteenth-Century China” by James C. Y. Watt and Denise Patry Leidy Amazon.com; “Paintings of the Ming Dynasty from the Palace Museum” by Guogiang Amazon.com; “Chinese paintings of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, 14th-20th century” by Edmund Capon and Mae Anna Pang Amazon.com; “In Pursuit of the Dragon: Traditions and Transitions in Ming Ceramics” by Idemitsu Bijutsukan. Amazon.com; “Objectifying China: Ming and Qing Dynasty Ceramics and Their Stylistic Influences Abroad” by Ben Chiesa, Florian Knothe, et al. Amazon.com; “The Wares of the Ming Dynasty” by R. L. Hobson Amazon.com; “A Treasury of Ming and Qing Dynasty Palace Furniture from The Palace Museum Collection” (2 Volumes) by Desheng Hu and Curtis Evarts Amazon.com; “Ming Dynasty Tales: A Guided Reader” by Victor H. Mair, Zhenjun Zhang Amazon.com; “The Urban Life of the Ming Dynasty” by Chen Baoliang, Zhu Yihua, et al. Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Ming Government and Art and Craftsmanship

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The Ming dynasty (1368-1644), with a highly centralized government, became increasingly plagued by political impasse and administrative rigidity toward the end. On the other hand, its folk culture expanded and thrived, commerce and economy grew robust and bustling, and the arts market was active and flourishing. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Artisans in every part of the country in the early Ming were required to work for the government, and the imperial workshops received substantial support from the Ming court, becoming the standard for craftsmanship. However, the quality of imperial production declined in the middle to late Ming, as master craftsmen could pay a fee in lieu of working for the imperial workshops, and the government began entrusting production to less-skilled craftsmen. The newly freed artisans began producing goods for society in general, and the quality available to ordinary citizens thereby improved.

“The late Ming was also a period of expanding freedom on many fronts. The material economy improved, as manifested through the evolving spending behavior and heightened demand for arts and crafts. The influence of ordinary citizens rose in society along with the status of craftsmen. Civilian production was elevated, and scholars became more engaged in artistic process. Foreign ideas also brought innovation to creativity in the arts and crafts. Each of these elements contributed to a lively and diverse artistic atmosphere.

“The late Ming Neo-Confucian philosophy of merging knowledge with action emphasized the practical and encouraged the learning of science. The ideological framework was eventually expressed in books of the late Ming. "Catalogue of Lacquer Decoration", written by Huang Ta-ch'eng in the T'ien-ch'i era (1621-1627), is the only surviving publication on ancient Chinese lacquer production; "Exploiting the Works of Nature" is a masterpiece by Song Ying-hsing on Ming dynasty arts and crafts. In the late Ming, many of the past experiences over the previous generations were compiled, and conclusions, commentaries, and records were produced. These texts not only allow a glimpse into the understanding of people and their knowledge at the time, but they have further implications and importance for people in modern times.

“Three waves of influence converged to generate the artistic achievements that occurred during the late Ming: the imperial family, scholars, and merchants. Though overlapping to a certain extent, these three main styles are manifested in the works of art from this period.

Colors and Auspicious Symbols in the Ming Era

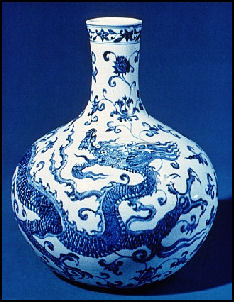

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““The Song Dynasty emphasis on minimalism and the intricate witnessed a great change by the late Ming period. During the middle and late Ming dynasty, the colorfully novel and effervescent "tou-ts'ai" and "wu-ts'ai" forms of porcelain decoration developed from the Yuan dynasty foundation of underglaze blue wares. Vessels also grew larger in size and cobalt produced a more vibrant blue, contrasting with the darker, colder shade of the early Ming. Low-temperature glazes were used and decoration was plentiful, creating a truly exciting and lively visual effect against the white background glaze. Such pieces represented some of the preferences of Ming taste. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The love of color was not limited to the decoration of ceramics. In addition to red, the palette of carved lacquer expanded to yellow, green, and even multi-colored. During the mid-Ming, enamelware became more readily available to the general public. Enamelware became increasingly popular in the middle Ming, reaching a peak in the late Ming. Colorful pieces of enamelware became an important part of the collection of ritual items at the imperial court. A variety of Western elements also found their way into the Chinese artistic vernacular.

“Apart from the dragon design representing the imperial family, decorative motifs also included symbols for good fortune, prosperity, and longevity. Equally prevalent was the practice of directly inscribing quotes onto vessels that pray for blessings. The popularity of designs such as the Eight Treasures, Eight Auspicious Symbols, Eight Divinatory Symbols, "ling-chih" spirit fungii, Eight Immortals, crane, lion, fish and water plants, and images of children playing (laden with allusions to Chinese history and mythology), combined with the abundance of colors and superior artistic expression, demonstrate the ideological foci of people at the time. For example, images related to auspiciousness often represent a play on words, such as that for "deer" in Chinese being a homonym for "official rank".

“Be it an auspicious symbol or multi-colored presentation, arts and crafts of the period were firmly rooted in a cultural profundity that had accumulated over time. Responding to the demands and preferences of the market, an animated and exquisite taste emerged. Examples of this include 1) “Monk with white glaze, mark of Shih Ta-pin Porcelain, late Ming to early Qing dynasty, 17th-18th century; and 2) Lotus-shaped dish with underglaze blue decoration of Sanskrit script, Ming dynasty, Wan-li period, 1573-1619.

Scholarly Appreciation and Collection of Antiques

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““Scholar-officials are guides to culture. However, the path to officialdom in the late Ming became increasingly blocked for scholars, and the political turbulence at the time also produced many who chose a life of reclusion or distance from the court, making for a group of figures who had a major influence on society. They focused on literature, the arts, and the pleasures of life. With many students, they also mingled among newly risen classes in society and merchant gentlemen. In the flourishing economy of the period, they helped form a new cultural trend. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Scholars revered classical civilization, considering antique objects to be symbols of cultivation and learning of the highest order. They believed that by studying and appreciating these antiquities, they would be able to become steeped in the didactic culture of the past. Almost everyone from the emperor down to merchants were inspired by scholars to imitate this lofty lifestyle, resulting in a new urban trend of collecting antiques in the hopes of demonstrating one's cultural refinement. Collectors consulted the scholars' expertise on connoisseurship and opened their collections to them for study. Printing also became increasingly accessible, with books such as "K'ao-ku t'u (Illustrated Antiquities)" and "Hsüan-ho po-ku t'u (Illustrated Hsüan-ho Antiquities)" even falling into the hands of the general public.

In order to satiate the mounting demand for ancient works of art, craftsmen were impelled to produce delicately styled goods that imitate the styles of antiques. Collectors, as investors, assumed the role of patrons for talented artisans and promoted further the improvement of their work. The financial power bestowed upon the industry stimulated pivotal developments in the creation and production of refined arts and crafts. Among the examples are: 1) Yellow-ground square basin with overglaze green decoration of phoenixes, porcelain, Ming dynasty, Chia-ching period, 1522-1566; and 2) FIowerpot in the shape of a dragon-fish Jade, FIowerpot in the shape of a dragon-fish Jade, Ming dynasty, 16th-17th century.

Independent Craftsmen, the Public and Flourishing Ming Economy

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““With changes in consumer culture, merchants were able to increase their profits. Also, as the number of officials, scholars, and ordinary folk engaged in business increased, merchants saw their status in society rise. At the same time, artisans with scholar status and points of view became increasingly common in the late Ming. Craftsmen with their ample experience produced exquisite works of art that catered to scholarly taste, with some scholars even providing the designs. The result was a form of interaction, in which skilled artisans received the praise of scholars, thereby elevating their renown and allowing them to command high prices and even compete on equal terms with the gentry. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Scholars provided craftsmen with new ideas, and artisans helped direct scholarly taste, the end result being decorative motifs associated with painting and calligraphy. Literati helped direct and design objects for the studio, sometimes even taking part in production. The cooperation and ties between the two raised the status of workmen and gained them respect. From each major production center emerged professionals of renown. The specialization reached a level close to the modern concept of establishing a unique brand — craftsmanship became superb and artisans received well-deserved attention and rightful compensation, even to the point where they could take part in civil service examinations, enter officialdom, and become outstanding members of society.

“The porcelain market flourished as demand by the imperial court and foreign markets escalated, resulting in private kilns being delegated by the court to produce most official wares in later periods of the Ming dynasty. With rising commercialization of products in the economy, artisans from official kilns could pay their way out of working for the imperial court. While official kilns went into decline, superior craftsmen trickled into local kilns, injecting new life and potential into the ceramics industry. With rapid developments in the middle and late Ming, production rose and porcelains were exported in increasing number. Private kilns expanded, and the famed Jingdezhen kiln, with its expertise dating back to the Five Dynasties period, helped the porcelain industry of the late Ming reach new heights, not only competing with official wares, but sometimes even exceeding them in quality. Examples: 1) Brush pot with rendition of a scene from ''The West Chamber'', mark of Chu San-sung Bamboo, Ming dynasty, 17th century; and 2) Yellow censer in the shape of a ting, mark of Chou Tan-chüan, Ming dynasty, 17th century.

Ming Dynasty Painting

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The reestablishment of an indigenous Chinese ruling house led to the imposition of court-dictated styles in the arts. Painters recruited by the Ming court were instructed to return to didactic and realistic representation, in emulation of the styles of the earlier Southern Song (1127–1279) Imperial Painting Academy. Large-scale landscapes, flower-and-bird compositions, and figural narratives were particularly favored as images that would glorify the new dynasty and convey its benevolence, virtue, and majesty. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“In Ming painting, the traditions of both the Southern Song painting academy and the Yuan (1279–1368) scholar-artist were developed further. While the Zhe (Zhejiang Province) school of painters carried on the descriptive, ink-wash style of the Southern Song with great technical virtuosity, the Wu (Suzhou) school explored the expressive calligraphic styles of Yuan scholar-painters emphasizing restraint and self-cultivation. In Ming scholar-painting, as in calligraphy, each form is built up of a recognized set of brushstrokes, yet the execution of these forms is, each time, a unique personal performance. Valuing the presence of personality in a work over mere technical skill, the Ming scholar-painter aimed for mastery of performance rather than laborious craftsmanship. \^/

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In the Mongol epoch, most of the Chinese painters had lived in central China; this remained so in the Ming epoch. Of the many painters of the Ming epoch, all held in high esteem in China, mention must be made especially of Qin Ying (c. 1525), Tang Yin (1470-1523), and Tung Ch'i-ch'ang (1555-1636). Qin Ying painted in the Academic Style, indicating every detail, however small, and showing preference for a turquoise-green ground. Tang Yin was the painter of elegant women; Tung became famous especially as a calligraphist and a theoretician of the art of painting; a textbook of the art was written by him. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

During the Ming Dynasty scholarly painting continued to prevail and ink wash painting of the Imperial Painting Academy and Southern Song court was briefly popular. Paintings were often filled with human figures, whose size was an indication of their rank. During the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties two approaches to scholarly painting were developed: the first in which artists copied and studied ancient themes and subjects, and the second in which artists abandoned models and expressed their own creativity through inventive means. The individualist expressive form predominated in the mid Qing dynasty. Research on ancient inscriptions influenced painting in the late Qing period. Hanging scroll portraits of emperors and other nobleman contained Tibetan and Islamic influences.

See Separate Article MING DYNASTY PAINTING AND ITS FOUR GREAT MASTERS factsanddetails.com

Ming Porcelain

Ming Dynasty ceramics were known for the boldness of their form and decoration and the varieties of design. Craftsmen made both huge and highly decorated vessels and small, delicate, white ones. Many of the wonderful decorations and glazes — peach bloom, moonlight blue, cracked ice, and ox blood glazes; and rice grain, rose pink and black decorations — were inspired by nature.

Ming Dynasty ceramics were known for the boldness of their form and decoration and the varieties of design. Craftsmen made both huge and highly decorated vessels and small, delicate, white ones. Many of the wonderful decorations and glazes — peach bloom, moonlight blue, cracked ice, and ox blood glazes; and rice grain, rose pink and black decorations — were inspired by nature.

In 1402, the Ming Emperor Jianwen ordered the establishment of an imperial porcelain factory in Jingdezhen. It's sole function was to produce porcelain for court use in state and religious ceremonies and for tableware and gifts. Between 1350 and 1750 Jiangdezhen was the production center for nearly all of the world's porcelain. Jiangdezhen was located near abundant supplies of kaolin, the clay used in porcelain making, and fuel needed to fire up kilns. It also had access to China's coast, which was used for transporting finished products to places in China and around the world. So much porcelain was made that Jingdezhen now sits on a foundation of shards from discarded pottery that over is four meters deep in places.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In the Ming epoch the porcelain with blue decoration on a white ground became general; the first examples, from the famous kilns in Ching-te-chen, in the province of Jiangxi, were relatively coarse, but in the fifteenth century the production was much finer. In the sixteenth century the quality deteriorated, owing to the disuse of the cobalt from the Middle East (perhaps from Persia) in favour of Sumatra cobalt, which did not yield the same brilliant colour. In the Ming epoch there also appeared the first brilliant red colour, a product of iron, and a start was then made with three-colour porcelain (with lead glaze) or five-colour (enamel). The many porcelains exported to western Asia and Europe first influenced European ceramics (Delft), and then were imitated in Europe (Böttger); the early European porcelains long showed Chinese influence (the so-called onion pattern, blue on a white ground). In addition to the porcelain of the Ming epoch, of which the finest specimens are in the palace at Istanbul, especially famous are the lacquers (carved lacquer, lacquer painting, gold lacquer) of the Ming epoch and the cloisonné work of the same period. These are closely associated with the contemporary work in Japan. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

See Separate Article MING DYNASTY PORCELAIN factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei ; \=/ Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021