YONGLE EMPEROR

Yongle Emperor

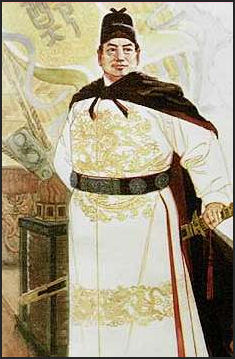

The Yongle Emperor (ruled 1403-1424) seized power from Zhu Yuanzhang's son with the help of a powerful group of court eunuchs. One of China's greatest emperors, he sent a great 300-ship armada to the Indian Ocean and Africa, restored the capital to Beijing, built the Forbidden City with a million workers, and invaded Mongolia and Vietnam.

Roberta Smith wrote in the New York Times, “Zhu Di (1360-1424), who would be called Yongle (Perpetual Happiness), is often compared to Peter the Great; the analogy fits in terms of brilliance, ambition, historical importance and brutality. Like Peter the Great, Yongle was a study in contradictions. A devout Tibetan Buddhist to the point of fanaticism, he ruthlessly executed not only his enemies but also their families and friends, sometimes in great numbers. And like Peter, he encouraged cultural openness, maintaining diplomatic ties with the Mamluk Empire based in Egypt and Syria, the Timurid Empire of Iran and Afghanistan and the Ashikaga shogunate in Japan. He also took full advantage of the accomplished workshops, populated by craftsmen from all of Asia, that the Yuan emperors had built. [Source: Roberta Smith, New York Times, April 1, 2005]

The great Yongle (pronounced YOONG-LUH) ruled China from 1403 to 1424. His father Zhu Yuanzhang, was the first Ming emperor, and a commoner who seized the throne after playing a leading role in the rebellion against the Mongol emperors of the Yuan Dynasty. Yongle, his fourth son, Smith wrote, “was not supposed to succeed him, and he didn't. The son of an older brother was named emperor when Yongle's father died in 1398, but after three years of civil war, Yongle drove him from the throne. He then set about laying the cultural, political and physical foundations that would sustain China for centuries to come. During his relatively brief reign, he moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing and vastly expanded the Forbidden City that 22 successive emperors would call home. He completed the Grand Canal connecting the Yangtze River to northern China and sent out six large armadas for trade and exploration. At home, he commissioned scholars to write an encyclopedia of classical and contemporary knowledge, which eventually numbered more than 11,000 volumes. His centralization of power and money was a particular spur to the decorative arts. Yongle's reign is considered the classic period for white porcelains and brought a revival of excellence in carved cinnabar lacquer.

Website on the Ming Dynasty Ming Studies mingstudies.arts.ubc.ca; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Ming Tombs Wikipedia Wikipedia : UNESCO World Heritage Site: UNESCO World Heritage Site Map ; Zheng He and Early Chinese Exploration : Wikipedia Chinese Exploration Wikipedia ; Le Monde Diplomatique mondediplo.com ; Zheng He Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Gavin Menzies’s 1421 1421.tv Matteo Ricci faculty.fairfield.edu Chinese History: Chinese Text Project ctext.org ; 3) Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MING- AND QING-ERA CHINA AND FOREIGN INTRUSIONS factsanddetails.com; MING DYNASTY (1368-1644) factsanddetails.com; HONGWU (ZHU YUANZHANG) AND OTHER MING DYNASTY EMPERORS factsanddetails.com; MING DYNASTY DOCUMENTS AND THEIR INSIGHTS INTO MING LIFE factsanddetails.com; EXPLORATION AND EUROPEAN INFLUENCES IN THE MING DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; QING- AND MING-ERA ECONOMY factsanddetails.com; MING-QING ECONOMY AND FOREIGN TRADE factsanddetails.com; WOKOU: JAPANESE PIRATES factsanddetails.com; CHINESE EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com; ZHENG HE: THE GREAT CHINESE EUNUCH EXPLORER factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Ming Dynasty: Its Origins and Evolving Institutions” (Michigan Monographs In Chinese Studies) by Charles O. Hucker Amazon.com; “From the Mongols to the Ming Dynasty: How a Begging Monk Became Emperor of China, Zhu Yuan Zhang” by Hung Hing Ming Amazon.com; “The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties” by Timothy Brook Amazon.com; “Ming Dynasty Tales: A Guided Reader” by Victor H. Mair, Zhenjun Zhang Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644, Part 1" by Frederick W. Mote, Denis Twitchett Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Volume 8, Part 2: The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644" by Denis C. Twitchett and Frederick W. Mote Amazon.com; “1587, A Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline” by Ray Huang Amazon.com; “Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle” by Shih-shan Henry Tsai Amazon.com; “The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty” by Shih-Shan Henry Tsai Amazon.com; “The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, 1618-44" by Kenneth M. Swope Amazon.com

Yongle’s Rise to Power

The Yongle emperor came to power by staging a rebellion in 1402 and deposing his nephew. He was helped by the eunuch Zheng He, today known as China's greatest explorer. Yongle means “Eternal Happiness." His devotion to Tibetan-Buddhism enabled him to forge a strong relationship with Tibet.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In Zhu Yuanzhang's last years (he was named T'ai Tsu as emperor) difficulties arose in regard to the dynasty. The heir to the throne died in 1391; and when the emperor himself died in 1398, the son of the late heir-apparent was installed as emperor (Huidi, 1399-1402). This choice had the support of some of the influential Confucian gentry families of the south. But a protest against his enthronement came from the other son of Zhu Yuanzhang, who as king in Beijing had hoped to become emperor. With his strong army this prince, Chengzu (Ch'eng Tsu) , marched south and captured Nanking, where the palaces were burnt down. There was a great massacre of supporters of the young emperor, and the victor made himself emperor (better known under his reign name, Yongle). As he had established himself in Beijing, he transferred the capital to Beijing, where it remained throughout the Ming epoch. Nanking became a sort of subsidiary capital. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“This transfer of the capital to the north, as the result of the victory of the military party and Buddhists allied to them, produced a new element of instability: the north was of military importance, but the Yangtze region remained the economic centre of the country. The interests of the gentry of the Yangtze region were injured by the transfer.

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: The nephew of Hongwu, founder of the Ming Dynasty, is popularly believed to have destroyed the lives of all those whom he met, and to have reduced to an uninhabited desert the whole region from the Yangtze River to Peking. After an ambitious youth had dispossessed his nephew, who was the rightful heir to the throne, he took the title of Yongle,, which became a famous name in Chinese history. To repair the ravages which had been made, compulsory emigration was established from southern Shanxi and from eastern Shandong. Tradition reports that vast masses of people were collected in Hongtong County in southern Shanxi, and thence distributed over the uncultivated wastes made by war. Certain it is that throughout great regions of the plain of northern China, the inhabitants have no other knowledge of their origin than that they came from that Hongtong [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

Rule of the Yongle Emperor

The Yongle emperor did everything in a big way. When he made his relatively frequent trips between the old capital of Nanjing and the new capital in Beijing his entourage was accompanied by 10,000 cavalry soldiers and 40,000 foot soldiers. The encyclopedia he commissioned, the Yongle Dadian, contained 11,099 volumes and was kept in the Hall of Literary Glory in the Forbidden City. Listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the largest publication and largest encyclopedia ever, it contained 22,937 chapters produced by 2,000 Chinese scholar between 1403 and 1408.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: The first Ming emperor had taken care to make his court resemble the court of the Mongol rulers, but on the whole had exercised relative economy. Yongle (1403-1424), however, lived in the actual palaces of the Mongol rulers, and all the luxury of the Mongol epoch was revived. This made the reign of Yongle the most magnificent period of the Ming epoch, but beneath the surface decay had begun. Typical of the unmitigated absolutism which developed now, was the word of one of the emperor's political and military advisors, significantly a Buddhist monk: "I know the way of heaven. Why discuss the hearts of the people?" [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

The Yongle emperor had a brutal side. One of his first acts after seizing power was torturing to death all those who opposed him. He was said to be particularly found of the death-by-a-thousand-cuts method of execution in which victims were bled to death very slowly and once declared that anyone was found with banned works "should be killed, together with their entire families." One victim, the great Confucian scholar Fang Xiaoru, was cut to pieces in a public square and 900 people associated with him were killed because he refused to express loyalty to the emperor.

Art from the Court of the Yongle Emperor

"Defining Yongle: Imperial Art in Early 15th-Century China" was an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2005 that featured about 50 objects from court of the Yongle Emperor. The first show at the Met to focus on one Chinese ruler, it included paintings, sculpture, lacquer ware, metalwork, textiles, cloisonné and ivory. It was organized by Denise Patry Leidy, associate curator in the museum's department of Asian art, and James C. Y. Watt, the department's chairman. [Source: Roberta Smith, New York Times, April 1, 2005 |<|]

toothpick box

Roberta Smith wrote in the New York Times, the “show is a kind of tasting menu of those workshops' extraordinary capabilities and includes examples of all the imperial and Buddhist art forms produced during Yongle's reign. On its own, nearly every object here is a kind of exquisite morsel...But together the objects illuminate the messy cultural openness of Yongle's court, reminding us that any culture is always an amalgam of many. In this case the amalgam included elements from India, Nepal and especially Tibet, as well as the Mamluk and Timurid cultures. |<|

“One vitrine displays a 15th-century Yongle period Ming porcelain blue and white basin beside a 14th-century Mamluk dynasty enameled glass basin. They are all but identical in shape and size, but the Mamluk basin is decorated with willowy Arabic script, while the Yongle basin is a controlled riot of scrolling vines of lotuses, chrysanthemums and peonies. A blue-and-white porcelain flask reflects the adaptation of an Islamic eight-pointed medallion, but the eight leaf-tip shapes nudging into its central circle introduce naturalistic (and painterly) inconsistencies that enliven the entire design. |<|

“Much of the power of this show resides in the details, and in the psychological intensity that exquisite craftsmanship and its tolerance for subtle variations can exude. This intensity legislates a kind of equality between different mediums and stylistic modes, especially the decorative and the representational. It is also reflected in the way certain motifs and devices migrate from object to object, and from art to life. A ritual staff and other ritual weapons made of iron inlaid with gold and silver are similar to those held by small gilt bronze statues of a sinuous Bodhisattva of Wisdom and a bristling multiheaded god, Yamantaka-Vajrabhairava; the detail in all three objects attests to the Yongle workshops' extraordinary level of craftsmanship in casting and metalwork. (Yamantaka-Vajrabhairava also appears, equally vehement, on an astonishing silk embroidery mounted like a Tibetan tangka, his 16 legs stomping evil spirits with precise, trill-like repetition.) |<|

“An intricate flywhisk made of woven and flowing palm-leaf fibers is a real-life version of a minuscule one that can be detected in a scene carved into a lacquer platter. On the platter, it is held by a servant attending scholars as they relax on a terrace, whose tile surface is detailed in fine tight patterns, as are the waves and starry sky beyond them and the leaves of several species of trees. The pictorial acuity of such carved-lacquer scenes finds an equivalent in three Tibetan-style paintings of Arhat, or enlightened beings, seated on rocklike thrones beneath trees. The exchange between the two mediums is one of several high points in this charged, not-so-little small show, which suggests that in the end the imperial art of Yongle may not submit to definition so easily.” |<|

Yongle Emperor, the Forbidden City and Other Projects

Yongle Encyclopedia

In 1409 Yongle, moved the capital of the Chinese Empire from Nanking to back Beijing in his effort to dominate the Mongol empire, the same way the Mongol's dominated Chinese empire. The Yongle emperor also vastly expanded the Grand Canal and the Great Wall and built hundreds of temples and palaces. His grand projects however drained the treasury and bled the country dry.

Yongle oversaw the construction of the "Violet-Purple Forbidden City"(the Forbidden City). Thousands of craftsmen, hundreds of thousands of laborers and building material from all over China were utilized in the project. Some scholars estimate that over two million laborers and craftspeople took part in the project. The basic outline of the palace was built between 1406 and 1420 under the Emperor Yongle. The majority of the five halls and 17 palaces that stand today were built after 1700.

The Yangshan Stone Tablet is a massive 31,000-ton monument created by Yongle to honor the founder of the Ming Dynasty. The size of skyscraper, it is located in an imperial quarry set among hills and canyons 15 miles from Nanjing. The idea was to create the world's largest monument in three parts: a base, steale and cap, that together would have stood 25 stories high. Thousands of workers spent years carving the stone from the mountain at great expense but ultimately the project was abandoned because no one could figure out a way to move the stones (even today it can't be done).

Great Ambitions of the Yongle Emperor

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Yongle Emperor, was particularly aggressive and personally led major campaigns against Mongolian tribes to the north and west. He also wanted those in other countries to be aware of China's power, and to perceive it as the strong country he believed it had been in earlier Chinese dynasties, such as the Han and the Song; he thus revived the traditional tribute system. In the traditional tributary arrangement, countries on China's borders agreed to recognize China as their superior and its emperor as lord of "all under Heaven." These countries regularly gave gifts of tribute in exchange for certain benefits, like military posts and trade treaties. In this system, all benefited, with both peace and trade assured. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Yongle Emperor, was particularly aggressive and personally led major campaigns against Mongolian tribes to the north and west. He also wanted those in other countries to be aware of China's power, and to perceive it as the strong country he believed it had been in earlier Chinese dynasties, such as the Han and the Song; he thus revived the traditional tribute system. In the traditional tributary arrangement, countries on China's borders agreed to recognize China as their superior and its emperor as lord of "all under Heaven." These countries regularly gave gifts of tribute in exchange for certain benefits, like military posts and trade treaties. In this system, all benefited, with both peace and trade assured. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu]

Because the Yongle emperor realized that the major threats to China in this period were from the north, particularly the Mongols, he saved many of those military excursions for himself. He sent his most trusted generals to deal with the Manchurian people to the north, the Koreans and Japanese to the east, and the Vietnamese in the south. For ocean expeditions to the south and west, however, he decided that this time China should make use of its extremely advanced technology and all the riches the state had to offer. Lavish expeditions should be mounted in order to overwhelm foreign peoples and convince them beyond any doubt about Ming power. For this special purpose, he chose one of his most trusted generals, a man he had known since he was young, Zheng He.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “After the collapse of Mongol rule in Indo-China, partly through the simple withdrawal of the Mongols, and partly through attacks from various Chinese generals, there were independence movements in south-west China and Indo-China. In 1393 wars broke out in Annam. Yongle considered that the time had come to annex these regions to China and so to open a new field for Chinese trade, which was suffering continual disturbance from the Japanese. He sent armies to Yunnan and Indo-China; at the same time he had a fleet built by one of his eunuchs, Zheng He (Cheng Ho). The fleet was successfully protected from attack by the Japanese. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Yongle and Zheng He's Expeditions

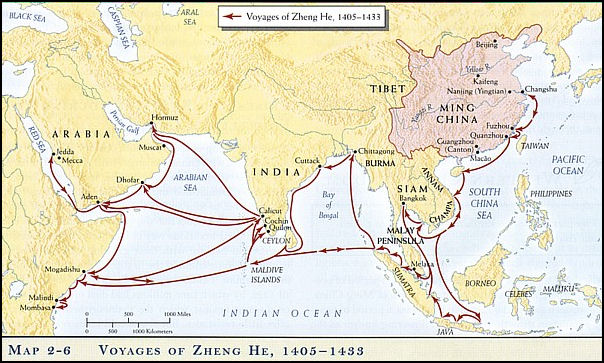

Zheng He, who had promoted the plan and also carried it out, began in 1405 his famous mission to Indo-China, which had been envisaged as giving at least moral support to the land operations, but was also intended to renew trade connections with Indo-China, where they had been interrupted by the collapse of Mongol rule. Zheng He sailed past Indo-China and ultimately reached the coast of Arabia. His account of his voyage is an important source of information about conditions in southern Asia early in the fifteenth century. Zheng He and his fleet made some further cruises, but they were discontinued. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

In the 3rd year of Yongle's rule, under the order of Ming Chengzu Zhu Di, Zheng He and his assistant, Wang Jinghong, led a fleet comprised of 317 ships, including 62 treasuredships and more than 27,000 people. They started from Liujia port, Suzhou, near Shanghai, and returned after more than two years. When arriving in each place, Zheng He exchanged porcelain, silk, copper and iron wares, gold and silver for local products."Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

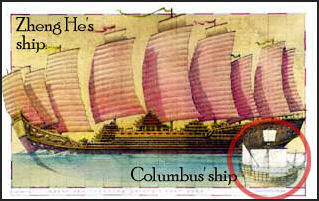

Sponsored by the Yongle Emperor to show the world the splendor of the Chinese empire, the seven expeditions led by Zheng He between 1405 and 1433 were by far the largest maritime expeditions the world had ever seen, and would see for the next five centuries. Not until World War I did there appear anything comparable. Overall He visited more than 30 countries and by some estimates covered 160,000 sea miles (about 300,000 kilometers).

The largest expedition utilized a crew of 30,000 men and a fleet of 317 ships, including a 444-foot-long teak-wood treasury ship with nine masts, the largest wooden ship ever made; 370-foot, eight-masted “galloping horse ships," the fastest boats in the fleet; 280-foot supply ships; 240-foot troop transports; 180-foot battle junks, a billet ship, patrol boats and 20 tankers to carry fresh water. The expedition was nothing less than a floating city that stretched across several kilometers of sea. By contrast to Columbus' expedition consisted for three ships with 90 men. The largest ship was 85 feet long. The largest ships in Vasco de Gama's fleet had four masts and were about 100 feet long.

The largest expedition utilized a crew of 30,000 men and a fleet of 317 ships, including a 444-foot-long teak-wood treasury ship with nine masts, the largest wooden ship ever made; 370-foot, eight-masted “galloping horse ships," the fastest boats in the fleet; 280-foot supply ships; 240-foot troop transports; 180-foot battle junks, a billet ship, patrol boats and 20 tankers to carry fresh water. The expedition was nothing less than a floating city that stretched across several kilometers of sea. By contrast to Columbus' expedition consisted for three ships with 90 men. The largest ship was 85 feet long. The largest ships in Vasco de Gama's fleet had four masts and were about 100 feet long.

The crew included sailors and mariners, seven grand eunuchs, hundreds of Ming officials, 180 physicians, geomacers, sail makers, blacksmiths, carpenters, tailors, cooks, merchants, accountants, interpreters that spoke Arabic and other languages, astrologers that predicted the weather, astronomers that studied the stars, pharmacologists that collected plants, ship repair specialists, and even protocol specialist that were responsible for organizing official receptions. To guide the massive ships, Chinese navigators used compasses and elaborate navigational charts with detailed compass bearings.

During the seven expeditions the treasure ships carried more than a million tons of Chinese silk, ceramics and copper coins and traded them for tropical species, gemstones, fragrant woods, animals, textiles and minerals. Among the things that the Chinese coveted most were medicinal herbs, incense, pepper, tropical hardwoods, peanuts, opium, bird's nests, African ivory and Arabian horses. The Chinese were not interested in Europe, which only had wool and wine to offer — things the Chinese could produce for themselves.

See Separate Articles ZHENG HE: THE GREAT CHINESE EUNUCH EXPLORER factsanddetails.com ; ZHENG HE'S EXPEDITIONS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

Yongle Emperor and the Giraffe

A big deal was made when a giraffe was delivered as a tribute to the Yongle Emperor from a ruler in Bengal in 1414. The Chinese believed the animal was a ch'i-lin (qilin) a Chinese unicorn with the "the body of a deer and the tail of an ox," which ate only herbs and harmed no living beings. Like the dragon, the ch'l-lin was said to be a being created by the surplus energy of the cosmos. Some historians believe that the emperor financed Zheng He's later expeditions with the understanding that he might be able to bring back equally interesting animals from Africa. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

In a lengthy paean the giraffe was compared with the Emperor's perfection:

Truly was produced a K'i-lin whose shape was high 15 feet

With the body of a deer and the tail of an ox, and a

fleshy boneless horn,

With luminous spots like a red cloud or a purple mist.

Its hoofs do not tread on living beings and in its wandering

it carefully selects its ground,

It walks in stately fashion and in its motion it observes a rhythm

It harmonious voice sounds like a bell or musical tube.

Gentle is this animal that in all antiquity has been since but once,

The manifestation of its divine spirit rises up to Heaven's abode.

Did the Yongle Emperor’s Extravagance Bring Down the Ming Dynasty

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Factions at court had long been critical of the Yongle emperor's extravagant ways. Not only had he sent seven missions of the enormous Treasure Ships over the western seas, he had ordered overseas missions northeast and east, had sent envoys multiple times across desert and grassland to the mountains of Tibet and Nepal and on to Bengal and Siam, and had many times raised armies against fragmented but still troublesome Mongolian tribes to the north. He had embroiled China in a losing battle with Annam (northern Vietnam) for decades (most latterly due to exorbitant demands for timber to build his palace). In addition to these foreign exploits, he had further depleted the treasury by moving the capital from Nanjing to Beijing and, with a grandeur on land to match that on sea, by ordering the construction of the magnificent Forbidden City. This project involved over a million laborers. To further fortifying the north of his empire, he pledged his administration to the enormous task of reviving and extending the Grand Canal. This made it possible to transport grain and other foodstuffs from the rich southern provinces to the northern capital by barge, rather than by ships along the coast.

“Causing further hardship were natural disasters, severe famines in Shantong and Hunan, epidemics in Fujian, plus lightning strikes that destroyed part of the newly constructed Forbidden City. In 1448, flooding of the Yellow River left millions homeless and thousands of acres unproductive. As a result of these disasters coupled with corruption and nonpayment of taxes by wealthy elite, China's tax base shrank by almost half over the course of the century.

“Furthermore the fortuitous fragmentation of the Mongol threat along China's northern borders did not last. By 1449 several tribes unified and their raids and counterattacks were to haunt the Ming Dynasty for the next two centuries until its fall, forcing military attention to be focused on the north. But the situation in the south was not much better. Without continual diplomatic attention, pirates and smugglers again were active in the South China Sea.

“The Ming court was divided into many factions, most sharply into the pro-expansionist voices led by the powerful eunuch factions that had been responsible for the policies supporting Zheng He's voyages, and more traditional conservative Confucian court advisers who argued for frugality. When another seafaring voyage was suggested to the court in 1477, the vice president of the Ministry of War confiscated all of Zheng He's records in the archives, damning them as "deceitful exaggerations of bizarre things far removed from the testimony of people's eyes and ears." He argued that "the expeditions of San Bao [meaning "Three Jewels," as Zheng He was called] to the West Ocean wasted tens of myriads of money and grain and moreover the people who met their deaths may be counted in the myriads. Although he returned with wonderful precious things, what benefit was it to the state?"

“Linked to eunuch politics and wasteful policies, the voyages were over. By the century's end, ships could not be built with more than two masts, and in 1525 the government ordered the destruction of all oceangoing ships. The greatest navy in history, which once had 3,500 ships (the U.S. Navy today has only 324), was gone.”

Image Sources: Zheng He, wikipedia; Zheng ship, Ohio State University; Zheng He expeditions, Dr. Robert Perrins, 1421; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021