COPYING, FORGERIES AND FAKES IN CHINESE ART

Copy artist in Imperial times

New York Times art critic Holland Carter wrote, "Debates about authenticity have always been part of art in China, where 'originals' are often chimerical things, creative copies are revered as supreme masterpieces and distinctions between copying and forging are fuzzy." What is regarded as fake in the West is often treated with great reverence in China. Even great Chinese masters copied works of their predecessors right down to their signatures and seals. Chiang Dai-chein, regarded by many as China's greatest 20th century artist, was an expert forger who sold thousands of paintings attributed to classic painters. The wide availability of counterfeit goods and indifference to copyright laws today shows the notions of individualism and individual ownership remain weak in China.

David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox wrote in the New York Times: “In China, the tradition of copying reflects more than a simple reverence for the past; it is an appreciation that beauty has been captured in a fashion worth emulating. Unlike the West, where “the shock of the new” is admired, China values tradition, and its best-selling works often pay homage to, and look like, those made hundreds of years earlier. At prestigious art schools, students engage in what the Chinese refer to as “lin mo,” or imitating the masters. Forgery and fraud are not necessarily part of the tradition, experts say, though famous painters like Zhang Daqian, who died in 1983, took pleasure in fooling the experts. [Source: David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox, New York Times, October 28, 2013]

"The inspiration of nature and past masters," wrote Boorstin, "gave a special kind and continuity, originality, and inwardness to painters. ...Forgery acquired a new ambiguity. The Chinese artists' proverbial talent for copying leads reputable art dealer nowadays to be wary of offering 'authentic' old Chinese paintings. Seeking constant touch with the past and the works of great masters by hanging pictures on the wall in rotation according to the seasons or festivals, the Chinese created a continuing demand that supported workshops for mass production by professional painters. These artists following the Tao showed remarkable skill in making both new originals and copies of copies.” [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Michele Cordardo, the director of the Central Conservation Institute in Rome, was invited to China to work in Xian. He told The New Yorker, "The Chinese have a different sense of the value of original and copy...The Chinese...have a tradition of conserving by copying and rebuilding...This system of considering by copying or rebuilding works well as long as you keep the artisan traditions intact. The problem is that those traditions have broken down in China...Once the continuity of Chinese imperial civilization came to an end knowledge of traditional pigments, resin, and textiles, and techniques of painting, wood carving or building quickly began to disappear."

Zhao Xu And Su Qiang wrote in the China Daily:““The painter Qian Xuan (1239-1299) was a prodigious user of personal hallmarks. Qian, who lived in a time of dynastic change, admitted to having signed works with "a byname never used before", in order to "stop and shame my imitators". What makes this particularly remarkable is that Qian, also a much-celebrated poet and essayist, had long championed the view that true artists should not be influenced in their creative work intent to pander, and that their works certainly should not be traded for money. [Source: Zhao Xu And Su Qiang, China Daily, December 19, 2015]

See Separate Articles: 20TH CENTURY CHINESE ARTISTS: QI BAISHI ZHANG, DAQIAN AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com ; MAO ERA ART factsanddetails.com ; MODERN ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE MODERN ARTISTS: CAI GUO-QIANG, ZENG FANZHI, WANG GUANGYI AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com ; AI WEI WEI: HIS LIFE, ART AND POLITICAL ACTIVITIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SHOCK ART, BODY PARTS, PHOTOGRAPHERS AND VIDEO AND GRAFFITI ARTISTS factsanddetails.com ; LOOTING CHINESE ART AND ARTIFACTS AND TRYING TO GET THEM BACK factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART MARKET: COLLECTORS, AUCTIONS, HISTORY, PROFITS AND BRIBERY factsanddetails.com ; HIGH PRICES PAID FOR CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Art Scene China Art Scene China ; Artron en.artron.net ; Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk ; Graphic Arts washington.edu ; Yishu Journal yishujournal.com ; Asia Society asiasociety.org ; Art in Beijing Factory 798 in Beijing Wikipedia Wikipedia; Communist China Posters Landsberger Posters ; More Posters chinaposters.org ; More Posters still Ann Tompkins and Lincoln Cushing Collection

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “A Modern History of China's Art Market” by Kejia Wu Amazon.com; “Chinese Antiquities: An Introduction to the Art Market (Handbooks in International Art Business) by Audrey Wang Amazon.com; “Collecting Chinese Art” by Sam Bernstein Amazon.com; “Collecting Chinese Art: Interpretation and Display” by Stacey Pierson Amazon.com; “Private Passions: Connoisseurship in Collecting Chinese Art” by Sam Bernstein Amazon.com; “The Compensations of Plunder: How China Lost Its Treasures” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com ;

Fakes in the Chinese Art Market

David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox wrote in the New York Times: The art market in China “is flooded with forgeries, often mass-produced, and has become a breeding ground for corruption, as business executives curry favor with officials by bribing them with art. “The market is in a very dubious stage,” said Alexander Zacke, an expert in Asian art who runs Auctionata, an international online auction house. “No one will take results in mainland China very seriously.” Indeed, even as the art world marvels at China’s booming market, a six-month review by The New York Times found that many of the sales — transactions reported to have produced as much as a third of the country’s auction revenue in recent years — did not actually take place. [Source: David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox, New York Times, October 28, 2013]

“Fraud is certainly no stranger to the international art world, but experts warn that the market here is particularly vulnerable because, like many industries in China, it has expanded too fast for regulators to keep pace.” In addition, China’s “reverence for the cultural past is now contributing greatly to the surge in forgeries. Artists here are trained to imitate the old Chinese masters, and they routinely produce high-quality copies of paintings and other works, such as ceramics and jade artifacts. That tradition has intersected with the newly lucrative art market, in which reproductions that so many have the skills to create are often offered as the real thing. It would be hard to create a more fertile environment for the proliferation of fakes. “This is the challenge right now,” said Wang Yannan, the president and director of China Guardian, the nation’s second-biggest auction house. “In the mind of every Chinese, the first question is whether it’s fake.”

“For years, much of the forgery went unnoticed as works passed from buyer to buyer, their prices spiraling up. But, increasingly, high-profile scandals are exposing the extent of the fakery and sowing doubts about the larger market. In one case, three years ago, an oil painting attributed to the 20th-century artist Xu Beihong, which sold at auction for more than $10 million, turned out to have been produced 30 years after the artist’s death by a student during a class exercise at one of China’s leading arts academies.

“Even more embarrassing was the government’s decision last July to close a private museum in Hebei because of suspicions that nearly everything in it — all 40,000 artifacts, including a Tang dynasty porcelain vase — were fake. “There’s always been forgers on the market, but it’s a matter of proportion,” said Robert D. Mowry, a former curator of Asian art at Harvard who is now a consultant for Christie’s.

“It is easier to detect fakes, of course, when the artists are still alive. Artron recently collected 100 works attributed to a popular painter, He Jiaying, and, with his help, determined that about 80 were fakes. “Basically, everything is controlled by middlemen,” said Wu Shu, a writer who has posed as an art dealer and published three books on the subject, including, “Who Is Swindling China?” “They generally divide the goods into three categories: the best-quality things go to the auction market; midlevel works go to the antiquity markets; and lower-level things go to flea markets,” Mr. Wu said.

“Experts say some Chinese dealers and consignors slip works into auction by doctoring old sales catalogs to invent a provenance, and — if all else fails — paying an auction house specialist to include a suspect item. Auction houses need impressive consignments to attract collectors, and experts say that, in their desperation for inventory, many have ordered forgeries. “I would say 80 percent of the lots at small and medium-sized auction houses are replicas,” said Xiao Ping, a prominent painter who formerly worked as an authentication adviser to the Nanjing Museum. Immortal Creativity

Producers of Fake Art in China

Modern Copy artist

David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox wrote in the New York Times: The stool and dressing table were a set, carved from jade and said to date from the Han dynasty, some 2,000 years ago. Their sale at auction in Beijing in 2011 ago drew $33 million and lots of fanfare. But then experts began pointing out that Chinese did not sit on chairs during the Han dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220). They sat on the floor. Eventually, a leader of the jade trade in Pizhou, a village in Jiangsu Province in eastern China, acknowledged that the pieces had been created by craftsmen there in 2010. [Source: David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox, New York Times, October 28, 2013]

“Wang Rumian, former president of the Pizhou Gemstone and Jade Industry Association, said in an interview in September 2013, that it had been the art dealers, not the craftsmen, who chose to pass off the set as ancient. “It wasn’t made that well,” he insisted. But it was good enough to fool the Chinese art market and draw a record price for jade that year.

“The trail of phony “antiques,” bogus paintings and fake bronzes winds throughout China these days. In Jingdezhen, a city in the rugged mountains of southeast China, small workshops produce exquisite reproductions of Ming and Qing dynasty porcelain, the craftsmen going to some lengths to build the wood-fired kilns that help create the subtle textures and glazes. In Yanjian, a dusty village in central Henan Province, they use ammonia on bronze to induce corrosion and produce that same greenish, oxidized patina that comes from exposure, allowing a bell or ritual wine vessel made a few days ago to pass for an artifact unearthed from a tomb. And in Beijing, Tianjin, Suzhou and Nanjing, highly skilled painters and calligraphers are replicating the brush strokes of revered masters.

“So-called traditional Chinese paintings typically depict the natural beauty of mountains, rivers and forests in an ancient style, and, together with calligraphy, are the workhorses of China’s art market, accounting for nearly half the money taken in at auction last year. So, throughout the country, painters work to copy masters like Qi Baishi and Fu Baoshi. “I’ve seen 700 to 800 people in a painting workshop, with a clear division of labor, making the works of Qi Baishi,” says Zhang Jinfa, a professional arts authenticator based in Beijing.

“A study last year by Artron, an art data company based in China, estimated that as many as 250,000 people in about 20 Chinese cities may be involved in producing and selling fakes. Visits to several of these cities in recent months documented that such production centers are thriving. Thousands of people in Jingdezhen, the ancient center of porcelain making, are employed by its bustling workshops, where bare-chested craftsmen sit hunched over, spinning clay into ancient forms. Down the production line, painters dip their brushes in ink and copy the outlines of flowers or traditional Chinese patterns onto the pottery. Often, the images are taken directly from auction catalogs that are pressed open on a nearby table.

“One of the best-known ceramic reproduction makers in Jingdezhen is Xiong Jianjun, who spent eight years making a copy of a Qianlong vase at the request of the National Museum in Beijing. “You need to study the fundamentals and decipher what they did back then,” said Mr. Xiong, who said some of his reproductions have been sold without his consent as antiquities.

Librarian Who Discovered Fakes Becomes a Master Faker Himself

Austin Ramzy wrote in the New York Times’s Sinosphere: “A librarian who admitted to a court this week that he substituted his own paintings for works by Chinese masters, and then sold the originals at auction, insisted he was not the only one to carry out such fraud. He was simply the best at it. Xiao Yuan, the author of several books on Chinese art and a former librarian at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, said he came up with the scheme when he began a project to digitize the school’s collection in 2003 and noticed that many originals had been replaced with fakes. That was what gave him the inspiration to do it himself, he told the court on Tuesday, according to a video of the proceedings. “At that time, when I first looked, I realized there were already many fakes that had already been substituted before me, but I didn’t say anything,” he said. “I was very greedy and tempted. How was it that in the past there were so many people who did this? Now I had the keys, and I could do it, too.” [Source: Austin Ramzy Sinosphere, New York Times, July 22, 2015]

“A year later he began visiting the library on weekends, taking home works by famous painters such as Qi Baishi and Zhang Daqian, then copying them himself. He avoided the best-known works, including the more impressionistic paintings of the Lingnan School, which scholars at the institution knew well and were likely to be lent out for exhibitions. Mr. Xiao purchased centuries-old blank paper and ink to render his forgeries and boasted that no one at the school’s library could tell the difference. “From then up to the present, no one else understood except me,” he said. “They just understood how to keep track of the numbers.”

“Prosecutors said that Mr. Xiao sold 125 paintings valued at 34 million renminbi, about $5.5 million, through auction houses. He also still had in his possession 18 works from the library with a total estimated worth of 77 million renminbi. He told the court that auction houses had thought those works were fake and had refused to sell them. “He was discovered after a Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts graduate noticed a work at auction in Hong Kong had the school’s seal.

“Mr. Xiao told the court he stopped swapping his fakes for the school’s real works in 2006, after the collection was moved to the school’s new campus, restricting his access. Upon seeing some of the collection later, he noted that some of his forgeries had been replaced with even cruder fakes. “I realized that paintings I had substituted 10 years ago had been substituted again,” he said. “I could tell right away they weren’t mine. The quality was too low. I pointed this out to people, but they didn’t pay any attention.”

Great 20th Century Chinese Painters and Forged Art

Zhang Daqian (Chang Dai-chein) (Zhang Daqian, Chang Dai-she, 1899-1983) is generally recognized as China's greatest 20th century painter. Born in Sichuan and regarded as a non-conformist, who worked briefly as a private calligrapher for a bandit, he mastered nearly all China styles and produced 30,000 paintings. He lived many years in South America and kept a pet gibbon. Chang was an expert forger who sold thousands of paintings attributed to classic painters. Zhang Daqian, took pleasure in fooling the experts. “Zhang Daqian felt he was an equal to the old masters,” Maxwell K. Hearn, chairman of the Asian art department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, told the New York Times. “And so the true test was whether he could copy them.[Source: David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox, New York Times, October 28, 2013]

Qi Baishi (1864-1957) is regarded as one of the greatest contemporary painters in China. He was influenced by Western styles but is considered by some to be the last great traditional painter of China. He painted a variety of subjects and was praised for the “freshness and spontaneity that he brought to the familiar genres of birds and flowers, insects and grasses, hermit-scholars and landscapes”.

David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox wrote in the New York Times: “The rising values and popularity of Qi’s art have led to a flood of fake Qi Baishis on the market. Liu Xilin, editor of “The Complete Works of Qi Baishi at the Beijing Fine Arts Academy,” said about half the Qi Baishi works that come up for auction in China are fake. “I can see that by just looking at their catalogs.” In the past 20 years, works attributed to Qi Baishi have been put up for auction more than 27,000 times in China. In one sign of the mania, 5,600 works attributed to Qi Baishi came on the market in 2011, up from 381 works in 2000. Auction records, though, show that more than 18,000 distinctive works by Qi Baishi have been offered for sale since 1993, an impossible number, if the expert estimates are right. [Source: David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox, New York Times, October 28, 2013]

See Separate Article 20TH CENTURY CHINESE ARTISTS: QI BAISHI ZHANG, DAQIAN AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com

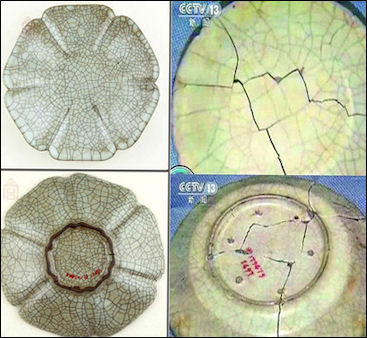

Priceless Song Porcelain Broken at China's Palace Museum

The Palace Museum in Beijing has confirmed a claim made by a netizen that a priceless porcelain. dating from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) has been broken. Long Can disclosed on Sina Weibo, China's equivalent of Twitter that an item of Ge porcelain ware, one of 1,106 pieces of first-grade porcelain in the Palace Museum, was broken into six pieces by a staff worker, according to Jinghua Times in Beijing. [Source: J. L. Young, Want China Times, July 31, 2011, Leo Lewis, Times of London, August 2011]

After the message was posted on Weibo, it was reposted by tens of thousands of netizens over the course of a few hours. Following this, the museum made an announcement that the porcelain ware was broken into six pieces by a staff worker who was doing non-destructive analysis and testing. The plate was in the jaws of precision testing which the worker accidently programmed to squeeze too hard. The announcement also said that right after the incident happened, all the testing works were stopped and the incident was reported to the authority. Many netizens suspected that the museum intended to conceal the fact, not wishing for a repeat of the embarassment when a thief made off with a number of watches from a visiting exhibition.

The broken work was a celadon-glazed masterpiece from the Fe Kiln. The worker who broke its is said to have a Master’s degree and seven years experience in the laboratory. Experts in Chinese antiques have estimated that the price of a well-preserved porcelain ware from Ge kiln is worth over 100 million yuan (US$15,530,000). In a 2008 auction at Sotheby's in Hong Kong, a Ge porcelain counterfeited during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) was sold for 3.28 million yuan (US$509,710).

In one of his early acclaimed works, according to the New York Times, a series of three photographs called "Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn", the Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei dispassionately shatters a priceless ancient Chinese vase, striking a theme — destruction and recreation — that runs through much of his art. Other works employ Ming and Qin period urns, furniture and architecture, assembled into haunting new creations, or painted over, Warhol-style, with the Coca-Cola logo, or speared by wooden beams. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, November 27, 2009]

Payment Defaults in the Chinese Art Market

David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox wrote in the New York Times: “The forgery problem helps account for the soaring number of payment defaults. Between 2009 and 2013, a study of sales at mainland auction houses by the China Association of Auctioneers found that about half the sales of artworks worth more than $1.5 million — a major portion of the market — were not completed because the buyer failed to pay what was owed. (For major auction houses in the United States, the default rate for works of the same value is negligible, several experts said.) ““It has something to do with the general environment in China,” said Zhang Yanhua, the association chairwoman. “As you know, China is still trying to build the rule of law in this country.” [Source: David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox, New York Times, October 28, 2013]

“Other explanations for the wave of defaults and late payments, experts say, include instances in which bidders got buyer’s remorse or just bid up a price to increase the value of works by a particular artist they collect. And then there are the payment problems that arise because China’s art market is, economically speaking, so young, and its rich are so recently minted. “There is still a big difference between East and West in understanding whether raising a paddle at an auction is actually a binding contract or not,” said Philip Tinari, director of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. “Some young starlet buys a bunch of paintings at an auction, walks out and says, ‘Nos. 13, 11, 7, 6, 5 those are the ones I don’t want.’ It happens all the time.”

In an interview in September 2013, Kou Qin, director and vice president of China Guardian, described the nonpayment problem in the market as “a very bad phenomenon,” but one that will be fought. His company reduced its nonpayment rate for the most expensive items to 17 percent last year. “Lack of honor,” he said. “It is a problem faced by the whole of society.”

“Auction houses have typically papered over the nonpayments, reporting aborted transactions as true sales, even posting record prices and seldom correcting the record. This has misleadingly burnished their revenues, making the market seem hotter and propping up prices, industry experts said.

“The practice has so alarmed the Chinese authorities, who worry that it could undermine the credibility of the market, that the auction association and state bodies like the ministries of commerce and culture stepped in a few years ago. As part of a larger program of reforms, the association now collects nonpayment data and publishes its findings in an effort to expose malefactors. It not only encourages auction houses to blacklist buyers with a history of not paying, but also recommends that the houses require steep deposits from potential bidders. The government has canceled or suspended the licenses of 150 auction houses between 2008 and 2011 for a variety of problems, including the sale of fake items.

"Suzhou Fakes": Fineries of Forgery

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “the Chinese term "wei haowu," which can be translated as "spurious finery", derives originally from the great Northern Song artist and collector Mi Fu (1052-1107) in his critique of a calligraphic work entitled "Classic of the Yellow Court" attributed to Zhong You (151-230). At the time, Mi believed that, even though the work was a tracing copy from the Tang dynasty (618-907), the imitation was of such exceptional quality as to merit the use of "spurious finery" to describe and affirm its high artistic value. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

"Fineries of Forgery" here refers to fake but fine works of painting and calligraphy produced in the sixteenth to eighteenth century in Suzhou or with a Suzhou style. “These forgeries that had been provided with the names of famous masters from the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties are, regardless of quality, traditionally lumped together under the label of "Suzhou pian," or "Suzhou fakes." The large numbers of and wide range of subjects in "Suzhou fakes" serve as apt reminders of the "craze for antiquities" that spread in the late Ming and early Qing period along with the rise of painting and calligraphy as consumer items. The "fineries of forgery" from the late Ming and early Qing in the collection of the National Palace Museum demonstrate how commercial workshops at the time proceeded to reproduce works in the name of ancient masters and to employ the styles of such renowned Suzhou artists as Wen Zhengming (1470-1559), Tang Yin (1470-1524), and Qiu Ying (ca. 1494-1552) to meet the demands of consumers for this fashion. As such, these works fed into the vivid imagination of a public seeking famous literary allusions and popular auspicious themes in art, resulting in numerous "hot" products, such as "Up the River on Qingming" and "Shanglin Park," appearing on the market.

"Suzhou fakes," though originally made in commercial workshops, had the advantages of mass production and wide circulation, features that should not be overlooked. As a result, they actually are a vital medium for studying the dissemination of information, imagining of antiquity, and construction of knowledge starting from the middle Ming dynasty. "Suzhou fakes" even later managed to successfully enter the imperial collection of the following Qing dynasty. Having a direct impact on the formation of the Qing court academic style, these "fineries of forgery" came to play an important role in the development of later Chinese painting that has previously gone mostly unnoticed.

"Up the River on Qingming" Fakes

“Along the River During the Qingming Festival” — also known as "Up the River on Qingming", by Zhang Zeduan (early 12th architecture) — is arguably China’s most famous painting. One thing that means is that it has been copied many times, often with great care and craftsmanship. There are also many stories related to these copies. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei and “miscellaneous notes and stories, in the Ming dynasty the notorious Grand Secretary Yan Song (1480-1567) and his son coveted the handscroll painting of "Up the River on Qingming" by the Northern Song artist Zhang Zeduan, learned it was in the possession of the official Wang Yu (1507-1560), and demanded it from him. Unwilling to relinquish his prized work, Wang surreptitiously commissioned the artist Huang Biao (1522-after 1594) to make an exact copy and offered it instead. Yan and son thereupon reveled at acquiring the painting, considering it the best work in the family collection. Later, the mounter of the forgery, Tang Chen, unsuccessfully tried to extort money from Wang Yu, and the deception was revealed. Furious at being cheated, Yan and son had Wang Yu framed and ultimately beheaded in revenge. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

This story of literally "dying for a painting," which comes in many versions, involves characters from different levels of society, from the Grand Secretary down to an official, a painter, and a mounter. As it turns out, "Up the River on Qingming" as a "finery of forgery" by Huang Biao proved to be one of the most popular subjects among so-called "Suzhou fakes," demonstrating how this theme permeated almost every level of society at a time when the "craze for antiquities" and fineries of forgery became "trendy" consumer products among those with purchasing power.

Huang Biao was a professional artist of Suzhou who excelled at making copies of paintings. Legend has it that he did an imitation of "Up the River on Qingming" to be presented to the powerful Grand Councilor Yan Song (1480-1567) and his son instead of the twelfth-century original by Zhang Zeduan of the Northern Song. Scholars believe that he is one of the few artists representative of "Suzhou fakes" who can be clearly identified.

“The Nine Elders”, by Huang Biao (1522-after1594 during the Ming dynasty, is an ink and colors on silk handscroll measuring 27.2 x 193 centimeters. This painting is the only surviving one personally signed by Huang Biao. Dated to the equivalent of 1594, it was done at the advanced age of 74 by Chinese account. The composition is actually similar to "The Nine Elders of Huichang," a painting attributed to Liu Songnian in the National Palace Museum collection that is an example of Huang Biao copying an ancient work. Huang's inscription on this handscroll compares the rise and fall of painting to that of worldly matters. And he saw his own reworking of "The Nine Elders" as "reviving (that which is all but) extinct," in other words playing a vital role in continuing and preserving the past.

“Qingming in Ease and Simplicity”, attributed to Zhang Zeduan (early 12th c.), is an ink and colors on silk handscroll measuring 38 x 673.4 centimeters. Painted at the end of this scroll is a columnar rock, upon which is a signature that reads, "Submitted by Your Servant, Zhang Zeduan, Painter of the Hanlin (Academy)." Many of the shop signs in this painting, such as "Good-hand Sun's Steamed Buns" and "Pan's Milk-vetch Dumplings," correspond to the names of shops in Record of Dream Splendors at the Eastern Capital, a text from the Southern Song period of the Northern Song capital Kaifeng. However, the type of masonry used in the city wall here had not yet appeared in the Northern Song, and the depictions of landforms and vegetation reveal the influence more of Qiu Ying's (ca. 1494-1552) style. In addition, the combination of blue, green, and red washes for the buildings and palaces is typical of that found in "Suzhou fakes." Along with the spurious seals of Wang Shizhen (1526-1590) and Yan Shifan (1513-1565), these all point to this as being a late Ming dynasty work based on a Southern Song description of Bianjing (Kaifeng).

At the same time, it mentions Wang Shizhen's father and the famous story of "dying for a painting" involving Yan Song. Incorporating the bustling market atmosphere of that time, it makes for a careful (and innovative) Ming dynasty interpretation of the renowned "Up the River on Qingming" painting. The delicate delineation of the figures and their expressions as well as the bustling commercial activities are all marvelously rendered with great interest, making this a masterpiece among "Suzhou fakes."

If Suzhou Was the Source: The Forgeries Were Greatly Prized

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ Starting from the middle Ming dynasty, Suzhou had already become a center for culture and fashion in the Jiangnan region and the whole country, too. Suzhou-style clothing, furniture, and crafts as well as Suzhou gardens, painting, and even snacks became objects of emulation among competitors in other areas. Suzhou previously had had a long history of considerable "cultural capital," and painters learned and copied from the rich collections in Jiangnan to form their own unique styles, which became a trend among painting circles at the time. For example, "Emperor Minghuang's Journey to Shu" came into the collection of a member in the Xiang family, where the famous Suzhou professional painter Qiu Ying learned and copied from the ancients to create many of his own masterpieces. And with the display and critique of artworks at scholarly gatherings, a taste for and knowledge of painting and calligraphy in Suzhou gradually deepened and expanded. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Suzhou at this time flourished economically, and increasing numbers of people there had the desire and means to collect works of painting and calligraphy. Tempted by the profits to be made, many workshops appeared in the Suzhou area to produce "ancient paintings" for the market, and even some scholar-artists took part in manufacturing these forgeries. The set of hanging scrolls here ascribed to Qiu Ying consists of "ruled-line" paintings done after such works of his as "Towers and Pavilions in Mountains of the Immortals." This subject depicts famous palaces from antiquity complemented by poetry to create a product both opulent in appearance and full of cultural meaning, making it quite suitable for display in a reception hall. This kind of "Suzhou fake" bespeaking the pursuit of fine delicate detail, rich narrative meaning, and deep cultural roots became a new paradigm for "fineries of forgery" that won broad appeal.

The "Suzhou fakes" now in the National Palace Museum were once sought-after products revealing several different styles popular in collecting circles at the time. For example, one type is represented by "Spring Dawn in the Han Palace" and "One Hundred Beauties," works which offer an imaginatively romantic view of life in the ladies quarters of the palace. Suzhou workshops also manufactured narrative paintings based on famous literary works, such as majestic depictions of the imperial hunting grounds at "Shanglin Park" from "Ode on Shanglin Park" by Sima Xiangru (179-118 BCE). Paintings of immortals with obvious messages of long life, such as "Gathering of Immortals Offering Blessings" and "Offerings for Longevity at Gem Pond," were likewise popular along with such didactic and Confucian themes as "Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety" and "Explanations on Cultivating Rectitude." The works in this section of the exhibit, with title slips giving the names of masters including Zhou Fang of the Tang dynasty, Zhao Boju of the Song, Wang Yuan of the Yuan, and Qiu Ying of the Ming, often have rich colors of dazzling blue-and-green, feature detailed renderings of decoration on clothing and buildings, and emphasize scenery in the narratives, all of which are qualities reflective of these "Suzhou fakes."

The phenomenon of "multiple versions from a single source" seen among the works in this exhibit illustrates the fact that Suzhou fakes were commercial products made in large quantities. The varied quality of these versions also suggests there may have been price discrepancies on the market, and various themes but with similar styles, inscriptions, and seals and signatures point to the range and subject matter of Suzhou fakes. This part of the exhibition presents a fascinating display of Suzhou fakes divided into two rotations to accommodate all the alluring attraction of these "fineries of forgery."

“Noble Sons,” attributed to Zhou Fang (fl. ca. 780-ca. 810) of the Tang dynasty, is an ink and colors on silk handscroll measuring 39.6 x 327.7 centimeters. The title of this painting translated literally from the Chinese is "hoofs of lin," referring to a mythical beast and alluding to sons of the ruling family. The handscroll depicts the ladies' quarters of the inner palace, where we see children being bathed and playing. Although the painting certainly does not date back to the Tang dynasty, certain elements, such as the plump ladies and their high-waisted robes, indeed fit the Tang dynasty "Zhou style" as practiced and popular in the Ming dynasty. Such motifs as children bathing and teasing youngsters can likewise be found in other "Suzhou fakes" given to Zhou Fang. Also seen among the figures are those associated with the famous Ming artist Qiu Ying (ca. 1494-1552), such as the lady sitting on a throne chair, which appears in his "Spring Dawn in the Han Palace." Although figures are interspersed in the various scenes, each is individually rendered, this work representing a combination of motifs popular among Suzhou workshops at the time.

Fake Chinese Antiquities

The market for Chinese antiquities has also generated a slew of fakes from con-men hoping to make big bucks. "There are many fakes on the market, and there are probably more now because the price of these antiquities have increased dramatically," Tang Hoi-chiu, chief curator of Hong Kong's Museum of Art, told AFP. "There are some very good copies out there." [Source: AFP, February 2012]

AFP reported: “The problem was highlighted again last month when questions arose about the authenticity of a jade dressing table and stool from the Han dynasty, which had fetched about $35 million at a mainland Chinese auction. Experts are now publicly questioning the piece since Chinese were believed to have sat on the floor, not stools or chairs, during the ancient period which ran from about 206 BC to 220 AD, the South China Morning Post reported.

Facts and figures about the black market in antiquities are difficult to come by, although many fakes are produced in mainland China, said Rosemary Scott, international academic director to Christie's Asian art departments. Scott has seen fakes many times larger than they should be and other amateur mistakes that can make determining authenticity a 30-second operation. "Some are absolutely dreadful and some are very good," she said. "In one case, a person presented me with (a piece) that was taller than me when it's only supposed to be a foot tall." But other items can take weeks or longer to determine if they're genuine, demanding a rigorous checklist, she said. Auction houses have even pulled items displayed in pre-sale catalogues when doubts about their authenticity lingered. "Our reputation is paramount - it's what we stand by," Scott said.

Auction Houses Outfox Chinese Antiquity Fakers

Nicolas Chow places a magnifying glass against a Ming Dynasty vase to inspect the potter's 600-year old workmanship. Chow, the international head of Chinese ceramics and works of art at auction giant Sotheby's, points out layers of uneven bubbles invisible to the naked eye along the early 15th Century blue and white porcelain. The distinctive markings are just one tell-tale sign that experts rely on to determine if a piece is a multi-million dollar original or worthless fake. [Source: AFP, February 2012]

"That happens in the firing process - they did not have an even temperature in (kilns) during the 15th century," Chow said of the piece, which fetched nearly US$22 million at an auction in Hong Kong late last year, setting a world record price for Ming Dynasty porcelain. "The feel of the glaze is also incredibly important. Just running your hands over it will give you the answer. "Potters in the old days would do lots and lots of these, one after the other. They breathed it, they lived it. It's very difficult for fakers to recreate... But there is still a degree of fear in the market."

Auction houses use various means including carbon dating to pinpoint a piece's age, but that requires taking a value-denting sample and threatens to make an item less appealing to keen-eyed collectors. "You have to decide if it's worth it because (carbon dating) could make the piece less aesthetically pleasing or just plain disfiguring," Scott said. The art expert said she runs pieces through a slew of criteria before making a determination and often brings in colleagues to gauge their opinion. "Does it have the right shape?" she said. "Is it the right texture, the right colour, was it painted with the right kind of brush?"

And when a piece fetches a giant price tag, auction houses are sure to be flooded with offers of similar antiquities, though most don't pass muster. "Within a few weeks, we are being offered copies of that piece," said Pola Antebi, head of Chinese ceramics and works of art at Christie's Hong Kong. "The turnaround is pretty scary." Complicating matters, some Chinese emperors ordered underlings to recreate works from earlier periods, which do not count as fakes, while there are also genuine pieces that have been retouched over the centuries."That is a restoration issue, it is not an authenticity issue. But collectors prefer untouched, so something has not been altered in any way," Antebi said, adding that retouching can slash a piece's value by half or more.

Most genuine works come from established collectors, but ordinary people also tap auction houses to authenticate pieces that may have been in their families for years, or ones they bought without first confirming their credentials. "People's expectations of the value are quite high. So when you tell them (the piece) is not going to pay for school fees or their retirement, it's terribly difficult," Antebi said, adding that she delivers the news "as politely as possible." Auction houses are also on the look out for phony collectors who "just ask too many questions" when they are told a piece is not genuine, suggesting they are trying to learn how to make a more convincing fake that will evade detection, Scott said.

For Chow at Sotheby's, spotting fakes means taking stock of every minute detail, although experts are not keen to reveal all their secrets for fear they could fall into the wrong hands. "But after some time you just get a feel," Chow said. "If you lift 50 similar Ming vases and know this one is not the right weight, then you know something is wrong - it's like your bag with and without a laptop," he added. "I'm not saying fakers can't get one thing right, but to get it all right is really difficult."

Copying Art in China

Chinese artists working in factory-like conditions produce much of the world’s supply of copied Western art. They create reproductions of paintings by Van Gogh, Turner, Da Vinci, Klimt and others at a rate of several a day. China now dominates the under $500 art market the same way it dominates the toys, plastic goods and textiles industries. Works by Chinese artists have found their way into homes and markets around the globe, so much so that artists who sell their works at the Spanish Steps in Rome and along the beaches in Santa Monica feel threatened.

Dafen near Hong Kong and Shenzhen is ground zero for the copy art trade. In 1989 Hong Kong art dealer Huang Jiang came to Dafen because the rent and labor were cheap. With a few years he established one of the world's largest painting operations in Dafen, employing 300 people in the early 2000s. Of the 300 workers 100 were “designers” who did the original copy work and 200 other workers mostly engaged in raming. There are even some assembly line operation with one artist specializing in trees, another flowers, and another skies. On copyright issues, one dealer told Reuters, “When leaders or cultural officials come, they say: “These items are copyrighted, so just don’t put them on top."

By the mid 2000s, the works by modern Chinese artists had become so popular and fetched such jaw-dropping prices at auction house that copy artists became increasingly busy copying these works. An artist in Dafen that churns out works by Yue Minjun at a rate of about one every day or two told Reuters, “I have done hundreds of his paintings. Copies like this aren’t really hard at all. It just takes time.” Art dealers in Dafen say that contemporary Chinese works now make up 10 percent to 20 percent of their sales.

Reporting from Dafen, in 2016, Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “A Van Gogh still life hangs in a budget hotel room. An abstract, black and gray composition brightens a corporate office. A Paris street scene gathers dust in a kitschy bar. The artist behind any of these may well have been a resident of the Dafen Oil Painting Village, a community in the southern Chinese boomtown of Shenzhen that once produced 60 percent of the world’s imitation oil painting masterpieces. “The village, a labyrinth of low-lying tile buildings and dark, narrow alleys, is home to an estimated 5,000 workers and 800 shops, most of which sell huge stacks of imitation art. Its artists, many of them classically trained, spend their days painting replicas of masterpieces by Picasso, Warhol, Monet, Rembrandt and others, each a testament to China’s prowess at producing mass quantities of inexpensive things. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, July 9, 2016]

“Dafen was a farming and fishing village until 1989, when Huang Jiang, a Hong Kong entrepreneur and master art copier, moved there with about 20 other artists. The village was cheap, he told the state-run China Daily newspaper in 2011, and was only a short drive from Hong Kong. He had been selling a few dozen copied paintings each month to foreign buyers, most from the United States and Europe; knowing the market’s potential, he began teaching other artists his trade. Over the years, demand skyrocketed, the village blossomed and Huang grew rich. Graduates from China’s art academies flocked to Dafen; they’d train for three to six months, learning to paint up to 20 masterpieces a day. They’d specialize in certain forms: Renaissance portraits, floral still lifes, Monets. Nobody would mistake them for con artists — their works are unabashedly copies, and cost anywhere from a few dollars to a few hundred. Dafen’s painters have argued that the original works are in the public domain, as their artists died more than 70 years ago (though the Andy Warhol and Thomas Kinkade estates would probably disagree).

Chinese Copy Artists

China’s art schools churn out tens of thousands of skilled painters every year. Copying Western art is the only way many of them can earn a living from their art. Zhang Lining, an artist in Shenzhen, estimates he painted 2,000 Van Gogh before he reached age of 25. That is more than Van Gogh himself painted in his lifetime. Other artists produce landscapes and copies of famous paintings by other Western artists. They often work from post cards or art books. One told National Geographic, “I’d love to give up replication and follow my artistic dreams.

Some 8,000 painters worked in the Dafen Oil Painting Village as of the late 2000s. Some are trained artists. Others paint by numbers and churn out 20 Van Gogh Sunflowers a day. These works are hung outside like laundry to dry and are sold for $3.50 a piece. Typically the artists are paid around $200 a month and given room and board. The cost of paints, canvas and other materials is minimal. The company that employs them sells the paintings for around $25, including the frames. Shipping charges are $1 per painting. In the United States they are sold to furniture stores or traveling commercial art sales for $35 to $40, with customers paying between $100 and $125 for them.

A copyist can earn $1,500 to $4,500 a year. Some artists specialize in painting their customers face’s with a Mona Lisa body. Describing a copy artists who worked out of a government-supported artist colony near Lishui in Zhejiang Province Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker, ‘she didn’t have a favorite painter; there wasn’t any particular artist period that influenced her...The government had commissioned some European-style paintings of local scenery but Chen had no use for any of it. Like many young Chinese from the countryside she had already had her full of bucolic surroundings. She stayed in the Ancient Weir Village strictly because of the free rent, and she missed the busy city of Guangzhou where had previously lived.”

Copy Art Village Struggles as Demand Falls

Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Hard times have fallen on Dafen. As labor costs rise, printing technology improves and foreign customers look elsewhere, artists are struggling to survive. Some are hanging up their brushes entirely. “A lot of artists have given up and left,” said Xie, an art school graduate from the southeastern province of Jiangxi, as she hawked small Van Gogh replicas by the roadside. “Before, the international market was huge, and profits were high; we'd sell two or three paintings a day and be able to feed our families. Now we sell five or six, and we still can’t.” [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, July 9, 2016]

“Experts say that Dafen is a microcosm of China’s economy at large. Beijing is attempting to shed the country’s decades-old growth model — one based on manufacturing and investment — for a more sustainable, innovation-oriented economic future. Out are dingy factories; in are tech start-ups and shiny office parks. “The transition has been rocky. In 2015, China recorded its slowest growth in 25 years, and manufacturing workers in Guangdong province, a place once known as the “world’s factory floor,” have been among the hardest hit. “Dafen village is just like other coastal cities in Guangdong,” said Zhou Zhengbing, a professor at the Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing who researches China’s cultural economy. “They’re focused on labor-intensive products…. These years, the economy is slowing down, demand is decreasing, yet labor costs are going up. For all these reasons, there are limited opportunities for the people who work there.”

“Now, residents are trying to adjust their craft to accommodate the new economy. As foreign buyers flag, they’ve been targeting the domestic market, swapping their Picassos for traditional Chinese landscape paintings and bright, colorful portraits. They’re also spending more time on their work. Rather than churning out 15 imitation Warhols a day, they’re painting originals — and selling them at a premium. A village museum showcases some of the local talent: Their paintings depict wind-swept Tibetan nomads, determined People’s Liberation Army soldiers, young urban women speaking on cellphones.Paintings are displayed on a street in China's Dafen Oil Painting Village.

“Lin Jinghong, the owner of Hongyi Oil Paintings, a small shop stocked with paintings of horses, said that his business has been performing well with domestic tourists and wholesalers from Russia. “You build relationships, and people come back to you,” he said. “Only a few people leave — maybe they’re just bad painters. There are still opportunities here.” Yet he fears that improved printing technology could someday drive him out of business. “This is really scary,” he said. “It’s been a trend over the past two years or so. Hotels and other customers, now they're using printing services.”

“Liu Yaming, a shopkeeper and 17-year Dafen resident, was also optimistic about the village’s future. “Some artists are very creative, and the market will acknowledge them,” he said. “People start by copying, then they want to create their own things. That's a route to innovation.” He noted that most of Dafen’s paintings, especially its highest-quality ones, are not created on assembly lines; they’re painted by individuals. If a factory fails, its workers lose their jobs; if a Dafen workshop goes under, its artists still have the means to thrive. “Over the past 10 or 20 years here, people have just kept on adapting,” he said. “It's a place that emerged organically. So it's not just going to disappear.”

Image Sources: Palace Museum in Taipei ; Want China Times, Shanghaiist, Xinhua, Christie's

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021