LOOTING CHINESE ART

looted Summer Palace head

Looting is a serious problem in China. Looters have ravaged ancient tombs and archeological sites, taking priceless relics, armor, weapons, porcelain, bronzes, silk and ornaments. In many cases the looting is done by farmers, construction workers and criminal gangs. Many farmers have turned to looting because they make so little money from farming, their living expenses are high and looting presents an opportunity to make a lot of money quick that is hard to resist. According to one peasant saying: "To be rich dig up an ancient tomb; to make a fortune open a coffin." Evidence of looting is founded in the flashy clothes and nice homes owned by former peasant farmers.

Auctions, antique fairs and art galleries are filled with looted works. It is estimated that 80 percent to 90 percent of the Chinese art sold on the international market was somehow illegally obtained. Beginning around 1980, a stream of bronzes, ceramics and jades from Neolithic times to the 14th century began pouring into Western markets via Hong Kong. The objects originated on the mainland and most likely were looted from tombs. Over the years the amount of this kind of art available on the market has increased dramatically.

The looted articles are usually taken to Hong Kong, where they are given fake histories and documentation. Much of the valuable stuff ends up at antique shops and galleries in Hong Kong or auction houses and top galleries in the United States, Europe and Japan. In Hong Kong it is possible to buy Tang celadons, Ming bowls, even 2000-year-old terra-cotta and neolithic figures. It is widely believed that items are smuggled out the country with the help of bribed local- and high-level government officials.

By some estimates, there are around 100,000 looters in China. Experts guess that 300,000 to 400,000 ancient Chinese tombs were raided in China between 1980 and 2005, 220,000 tombs were broken into between 1998 and 2003 and 400,000 were raided between 1993 and 2013. Looting is particularly big problem around Xian, the home of the terra-cotta army and other archeological sites, and the city of Luoyang, the capital of at least nine dynasties. These areas are littered with imperial tombs that are mostly unguarded and easy pickings for looters. [Source: Lauren Hilgers, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2013]

Sometimes the art is stolen outright from museums, temples, archeological sites or government warehouses that store art and artifacts. A stone-carving of Buddha purchased for $2 million and displayed at the Miho Museum, near Kyoto, Japan, was stolen from an office in Boxing County in Shandong province in 1994. In 1997, a gang of thieves used a diamond saw and sledgehammer to knock off the head of a 7th century Akshobhya Buddha, one of four large statues of Buddha at the Four Gate Pagoda in Shandong Province. The thieves were caught soon afterwards but the head disappeared. In February 2002, it turned up as a gift from loyal disciples to a 73-year-old Buddhist master and founder of a meditation center. The Buddhist master alerted authorities. In December 2002 the head was placed back on the torso it was knocked off of.

See Separate Articles: LOOTING CHINESE ART AND ARTIFACTS AND TRYING TO GET THEM BACK factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART MARKET: COLLECTORS, AUCTIONS, HISTORY, PROFITS AND BRIBERY factsanddetails.com ; FORGING, BREAKING AND COPYING CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com ; HIGH PRICES PAID FOR CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Compensations of Plunder: How China Lost Its Treasures” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com ; “Foreign Devils on the Silk Road” by Peter Hopkirk (2006) Amazon.com; “A Modern History of China's Art Market” by Kejia Wu Amazon.com; “Chinese Antiquities: An Introduction to the Art Market (Handbooks in International Art Business) by Audrey Wang Amazon.com; “Collecting Chinese Art” by Sam Bernstein Amazon.com; “Collecting Chinese Art: Interpretation and Display” by Stacey Pierson Amazon.com; “Private Passions: Connoisseurship in Collecting Chinese Art” by Sam Bernstein Amazon.com

Chinese Looters

Lauren Hilgers wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Every archaeologist I met in my three years of writing about archaeology in China was familiar with the work of looters. One told me the tomb he was excavating had been raided multiple times — once a few hundred years ago, again in the 1970s, and finally just months before. At an underwater site near Guangzhou, local authorities were constantly chasing off free-diving thieves who tried to sneak by in the middle of the night. Tomb raiders are, by nature, hard to find. In general, archaeologists don’t like to talk about them because the scale of the problem makes it seem as if China is losing control of its history. [Source: Lauren Hilgers, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2013]

Tomb raiders work underground — literally and figuratively — and tend to hang out in the middle of nowhere, in places that were once on the periphery of great cities and rich trade routes. According to the officers who chase them, most are former farmers and peasants. They operate in gangs that teach new recruits how to find and excavate tombs, grabbing only the most desirable artifacts. What they take moves through the hands of middlemen to collectors and auction houses in China and around the world. What they leave behind is a source of endless frustration to archaeologists: damaged, incomplete sites that reveal only a fragmented picture of the past.

“The main character of the series is a reluctant looter, but he has no choice — it runs in the family. “Tomb raiding used to be a family business,” Liu said. “If your father is teaching you how to find a tomb and how best to dig, he is going to teach you the safest way to do it. There were fewer disputes.” Today, Liu continued, the relationships have changed. Tomb raiders are friends or acquaintances, or strangers brought together by larger criminal networks. And according to Liu, this can cause conflicts. He’s seen more than one operation fail when a disgruntled raider ratted out his compatriots. “Maybe someone thinks they aren’t getting paid enough,” Liu said. “Maybe they think things aren’t fair.” Though it is a centuries-old practice, the methods of tomb raiding have changed dramatically over the past 30 years, as the market for Chinese artifacts has exploded. Raiders have been caught with walkie-talkies, oxygen tanks, lights, and chainsaws.

Looting Operations in China

The looters usually work at night. It is not unusual for them to be half drunk. New recruits are often spooked about the idea of raiding tomb after a lifetime of listening to ghost stories. The work often involves tunneling. For those who go down the tunnels the work is very dangerous. It is not uncommon for the tunnels to collapse or the looters to be overcome by toxic fumes in the tomb. The looters who do the work are paid about $60 a night by middle men and dealers who make thousands of dollars off their work and have much fewer risks.

Lauren Hilgers wrote in Archaeology magazine: “A successful tomb raider can make a year’s salary in one night. Looters use metal rods to look for buried tombs, leaving telltale holes like these. If a rod punched into the ground encounters resistance, it could mean a tomb is below. “It’s a fact of our work,” said the archaeologist. Tomb raiders ruin excavation sites by taking what they think is valuable and trampling the rest. “Details that a looter doesn’t care about and destroys would otherwise have helped us better understand a site.” Evidence of construction techniques, the placement of objects in a tomb, and their potential significance can be lost. Despite this, Liu and his friend were surprisingly sympathetic to the raiders. “People here grow millet and corn and sometimes green beans,” Liu said. “There’s really no way to make much money.”[Source: Lauren Hilgers, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2013]

“Tomb raiders are difficult to catch, in part because of their efficiency. Teams survey large areas in advance by punching the ground with metal rods. “If there is just earth under you, the rod will go down easily,” Yuan said. “If there is a tomb, you will hit something hard.” Raiders then mark the sites and return later. In teams of eight to 10, they start as soon as it gets dark and work until two or three in the morning. In that time, they must dig a hole to the roof of the tomb wide enough for a man to enter, and then break through. There is more digging inside, along with identifying valuable artifacts and hoisting them back to the surface with ropes. Yuan pointed to footprints leading away from the hole and out of the field. “And then,” he said, “they get out of town.”

Sophisticated Looting Operations in China

Some of the looting operations can be quite sophisticated. In Xian a team of looters broke into the 2000-year-old tomb of the Empress Dou, a powerful Han dynasty dowager who died in 135 B.C., and made off with a huge cache of treasures. The tomb was located 131 feet below the surface inside a burial mound. With a tangon — a special shovel with a curved blade and steel screw-on handle extensions that can be used to extract sol samples from over 100 feet below the surface — the looters probed beneath the surface looking for things like charcoal — which ancient gravedigger placed around tombs for protection against moisture — to locate the best place to excavate. [Source: Time magazine]

To reach the tomb the gang dug a 115-foot-deep tunnel. To help them get started they used dynamite to blast a small crater at the surface to speed up the digging process. They were careful not use explosives powerful enough to cause the roof of the tunnel to collapse. Members of the gangs and their gear were lowered into the tunnel with a rope. An air blower powered by a portable generator pumped in fresh air from the surface. To reach the tomb roof a breach tunnel was built off the main tunnel. Saws were used to cut through the wooden-plank roof of the tomb.

Once inside the tomb the looters donned gas mask to filter out the stale air and toxic gases that have accumulated in the tomb as a result of decay. Without gas masks looters often pass out from the fumes. Police were alerting that looting was going on by villagers who smelled fumes from the explosives blown towards their a village. Three looters were arrested. Two got away. After the police left another gang penetrate into the tomb and made off with at least 2000 object, mostly ceramic statues (gold and valuable art is believed to be have carted away centuries earlier).

Some of the pieces were found by customs during a routine check of new ceramics. Others made their way to New York and were pulled from a Sotheby’s auction just 20 minutes before bidding on them was to began. They were eventually returned. Other pieces undoubtably did find buyers.

Scale and Sophistication of Looting in China Increases

auction selling Summer Palace heads

The Guardian reported in January 2012, “China's extraordinary historical treasures are under threat from increasingly aggressive and sophisticated tomb raiders, who destroy precious archaeological evidence as they swipe irreplaceable relics. The thieves use dynamite and even bulldozers to break into the deepest chambers — and night vision goggles and oxygen canisters to search them. The artefacts they take are often sold on within days to international dealers. [Source: Tania Branigan, Guardian, January 1, 2012]

Tomb theft is a global problem that has gone on for centuries. But the sheer scope of China's heritage — with thousands of sites, many of them in remote locations — poses a particular challenge. "Before, China had a large number of valuable ancient tombs and although it was really depressing to see a tomb raided, it was still possible to run into a similar one in the future," said Professor Wei Zheng, an archaeologist at Peking University. "Nowadays too many have been destroyed. Once one is raided, it is really difficult to find a similar one."

His colleague, Professor Lei Xingshan, said: "We used to say nine out of 10 tombs were empty because of tomb-raiding, but now it has become 9.5 out of 10." Their team found more than 900 tombs in one part of Shanxi they researched and almost every one had been raided. Wei said precious evidence such as how and when the tomb was built was often destroyed in raids, even if relics could be recovered. "Quite apart from the valuable objects lost, the site is also damaged and its academic value is diminished," he said.

Wei and Lei spent two years excavating two high grade tombs from the Western Zhou and Eastern Zhou periods (jointly spanning 1100BC to 221BC) and found both had been completely emptied by thieves. "It really is devastating to see it happening," Zheng said. "Archaeologists are now simply chasing after tomb raiders."

Experts say the problem became worse as China's economy opened up, with domestic and international collectors creating a huge market for thieves. Zheng said a phrase emerged in the 1980s: "If you want to be rich, dig up old tombs and become a millionaire overnight."

According to AFP: “The demand for Chinese antiquities has exploded, helping propel Hong Kong to third spot in the global auction market behind London and New York as collectors slap down eye-popping sums for a piece of the country's history. Helping drive the boom is a growing class of super-rich Chinese looking for opportunities to exploit their net worth while also "reclaiming" parts of Chinese history from Western collectors.Auction houses Sotheby's and Christie's together raised over $460 million from sales of Chinese antiquities and art works in 2011. [Source: AFP, February 2012]

Professional Looters in China and Their Audacity and Destructiveness of Looters

Officials say tomb thefts have become increasingly professionalised. Gangs from the provinces worst hit — Shanxi, Shaanxi and Henan, which all have a particularly rich archaeological heritage — have begun exporting their expertise to other regions. One researcher estimated that 100,000 people were involved in the trade nationally. Wei Yongshun, a senior investigator, told China Daily in 2011 that crime bosses often hired experienced teams of tomb thieves and sold the plunder on to middlemen as quickly as they could. Other officers told how thieves paid farmers to show them the tombs and help them hide from police.

Raiders return to a site repeatedly over months. In some cases, thieves have reportedly built small "factories" next to tombs — allowing them to break in without being noticed. Wei said: "Stolen cultural artifacts are usually first smuggled out through Hong Kong and Macao and then taken to Taiwan, Canada, America or European countries to be traded."

The sheer size as well as value of the relics demonstrates the audacity of the raiders — in 2011, the Chinese authorities recovered a 27-tonne sarcophagus that had been stolen from Xi'an and shipped to the US. It took four years of searching before China identified the collector who had bought the piece — from the tomb of Tang dynasty concubine Wu Huifei — for an estimated $1m (£650,000), and secured its return. In a particularly alarming case in 2011, raiders simply bulldozed their way through 10 newly discovered tombs in eastern Jiangxi province. The Global Times newspaper reported that pieces of coffins and pottery and iron items were scattered across the ravaged site, which was thought to date back 2,000 years. Archaeologists said further excavation was impossible because the destruction was so bad. [Source: Tania Branigan, Guardian, January 1, 2012]

Underwater Looting in China

Lauren Hilgers wrote in Archaeology magazine: The biggest threat to underwater archaeology, Cui says, is the popularity of the artifacts such sites carry. Unblemished, authentic Ming Dynasty porcelain can command high prices from collectors, and thieves have learned to target sunken ships to find it. According to the archaeologists at Nan'ao, keeping the wreck well protected has been the key to their success. However, they are on-site only a few months a year. The rest of the time, Nan'ao Number One is under the watch of one determined local law enforcement officer. "If we had no Zhu Zhixiong, we would have no Nan'ao," Cui says. [Source: Lauren Hilgers, Archaeology, September/October 2011]

Zhu, or Chief Zhu, as everyone on the boat calls him, is the head of Nan'ao Island's maritime border control. He is perpetually in uniform and has a tendency to stare, earnest and unblinking, when speaking about the Nan'ao. "When the fishermen uncovered the porcelain they wanted to keep it," he says. They discovered the Nan'ao's treasures while diving off the coast of the island in 2007 and set about building their collection in secret, hoping to attract the attention of a buyer. Instead, tales of the stash reached Zhu. "We run a program where we reach out to the local people and they feel comfortable talking to us," Zhu explains. "Somebody came to us and told us about the artifacts." The border patrol confiscated the porcelain and Zhu did his best to explain to other fishermen that retrieving and selling the artifacts is against the law.

"We didn't do this for glory," Zhu says. "We didn't know what was down there at that point. We don't dive, we can't see under the water, but we know it is important to protect our national heritage." Zhu dedicated himself to guarding a wreck he couldn't see. "This isn't just a Chinese problem," Zhu says carefully. "But thieves and treasure hunters are tireless." At the Nan'ao wreck, Zhu set up 24-hour surveillance. "They will come at night or in bad weather, thinking you won't chase them. Some of them are very professional." Some haul in diving gear and lights. Others are fishermen and experienced enough in the water to free dive 90 feet to the bottom. "One boat must have studied our habits and came in through an area we weren't patrolling. When we came with our boats they fled, but we saw, with complete clarity, where they were headed." Zhu's team called ahead to another guard base and caught the thieves.

Over the years, Zhu's reputation has spread. Patrol officers say they are seeing fewer attempts every year. Still, says Zhu, you have to be vigilant. "You can't sleep if you want to protect our heritage," he says. When Cui sees him on the deck of the Nan Tianshun, he gives him an affectionate pat on the shoulder and says, "Every wreck needs its own Chief Zhu."

Combating Looting in China

To combat looting 1) auction houses and antiques dealers are required to reapply every year for their licenses; 2) motion sensors and satellite devises have been installed at archeological sites and places with a lot tombs; and 3) volunteers have been marshaled to guard the best-known sites. Chinese law forbids the export of art more than 200 years old. The looting problem is still serious but many believed its is not as bad as it once was. Smuggling and looting was at its peak in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Since the 1990s, China’s security forces have stepped up their efforts, instituting harsh punishments for looting, working with the United States and Europe to stop smuggling, andcreating a national information center. Tania Branigan wrote in the Guardian in 2012, “Police have stepped up their campaign against the criminals and the government is devoting extra resources to protecting sites and tracing offenders. In 2011 it set up a national information centre to tackle crimes related to looting antiquities. Spending on protecting cultural relics as a whole soared from 765 million yuan in 2006 to 9.7 billion in 2011. [Source: Tania Branigan, Guardian, January 1, 2012

Luo Xizhe of the Shaanxi provincial cultural relics bureau told China Daily: "If we don't take immediate and effective steps to protect these artefacts, there will be none of these things left to protect in 10 years." He said provincial and national authorities planned to spend more than 100m yuan (£10m) on surveillance equipment for tombs in Shaanxi over the next five years. But video surveillance and infrared imaging devices for night-time monitoring cost 5m yuan for even a small grave, he added.

Local officials have insufficient resources to prevent the crimes and often do not see the thefts as a priority. Others turn a blind eye after being bribed by gangs. But international collectors bear as much responsibility for the crimes as the actual thieves: the high prices they offer create the incentive for criminals.

At least for a while China instituted the death penalty for smuggling cultural relics out of the country. Several looters who have been caught have received the death penalty. In 1987, some looters received the death penalty after they were caught trying to sell the head of one Xian's famous terra-cotta soldiers to a foreign dealer for $81,000. In May 2003, three men were executed for plundering tombs dating back to 2,000 years. In August 2010, the Chinese government said it was considering dropping the death penalty for smuggling cultural relics out of the country. [Source: AP]

Many feel that most effective measure would be import ban on antiques in Europe, Japan and the United States. Many looted items are believed to end up on the United States. Beijing has repeatedly urged Washington to adopt a ban on imports of any art or artifacts predating 1911. Thus far Washington has not responded in part because of fierce objection by art dealers and collectors. Some would like to see tough measures taken in Hong Kong as well. Demonstrations have been held there calling for an end to auctions where looted mainland art is sold

Impact Combating Looting in China

Explorer David Neel

The crackdown by authorities was helping to contain the problem to an extent. According to the ministry of public security, police investigated 451 tomb-raiding cases in 2010 and another 387 involving the theft of relics. In the first six months of that year, they smashed 71 gangs, detained 787 suspects and recovered 2,366 artefacts. Those caught face fines and jail terms of three to 10 years, or life in the most serious cases. [Source: Tania Branigan, Guardian, January 1, 2012

Lauren Hilgers wrote in Archaeology magazine: “ Tomb raiders today aren’t as brazen as they once were. In a famous case from 1997, reports estimated that more than 1,000 people were looting the ancient tombs built during the Tuyuhun Kingdom (A.D. 417 — 688) in China’s Qinghai Province. One archaeologist reported that as he excavated one side of a burial site, looters worked on the other. Looters today are just as determined, but perhaps not quite so bold or foolish. [Source: Lauren Hilgers, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2013]

“Just before my arrival in Henan, a story had broken about a tomb-raiding ring in Hubei, another province rich in both tombs and looters. Local farmers had reported finding holes surrounded by cigarette butts and litter. Investigators arrived and were able to arrest a group of what some Chinese media outlets characterized as “suspicious people from Shandong.” The arrested looters claimed that the artifacts they took had already been sold to a man called “Little Fatty” for 4 million yuan — around $643,000.

“Investigation into the mysterious Little Fatty led to a man named Zhang Moumou. Though Zhang had no apparent profession, he kept two apartments, and large sums of money frequently passed through his accounts. In his two homes, investigators recovered 198 stolen artifacts from all over the country. “The artifacts they recovered come anywhere from the Spring and Autumn Warring States period [771 — 221 B.C.] to the Jin Dynasty [A.D. 1115-1234],” Bao Dongbo, the director of the Hubei Provincial Archaeological Institute, told me. “When the police found those artifacts, they looked as they would have when first unearthed. The raiders have done no repair or cleaning.” Little Fatty was one of countless middlemen, a stopping point for artifacts passing between the hands of looters and the display cases of wealthy collectors.

“Their method of operation is actually very complicated,” said Bao. “Someone contributes money, someone else contributes labor, someone gives instructions, someone else does the digging. You know, no matter where you are, you can find people who want to make quick money.”

Who’s Responsible For Chinese Treasures in Western Museums

In the 1920s, Sven Hedin's Sino-Swedish excavations in Xinjiang and Manchuria unearthed 10,000 strips with writing, Han documents on silk, wall paintings from Turpan and pottery and bronzes. The most prominent of the Western explorers of the remote parts of China was Sir Aurel Stein (1863-1943), an explorer, linguist and archaeologist who made four expeditions to Central Asia in the early 20th century. Stein was Jewish and born in Hungary. He pioneered the study of the Silk Road and looted Buddhist art from caves in the western Chinese desert. Accompanied by his dog Dash, he carted away a treasure trove of ancient Buddhist, Chinese, Tibetan and Central Asia art and texts in a number of languages from the ancient city of Dunhuang and gave them to the British Museum.

In the late 1920s, Stein trekked over 18,000-foot Karakoram Pass three times and traced the Silk Road through Chinese Turkestan and followed routes on which Buddhism spread to China from India. Stein discovered the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas near Dunhuang in northwest China and carted away 24 cases of artifacts, including silk painting, embroideries, sculptures and 1,000 early manuscripts written in Tangut, Sanskrit and Turkish, which included the world's oldest book, The Diamond Sutra.

When news got out about Stein's discoveries it set in motion and age of discovery and looting. During the first quarter of the 20th century, archaeologists from Great Britain, Russia, Germany, Japan and other nations competed for shares of Silk Road treasure. These archaeological exploits even got tangled up in what has been termed the Great Game where Great Britain and Russia competed for political influence in Central Asia and Western China. Christian missionaries also made their way out to Xinjiang. Among the most famous were Francesca French and Mildred Cable who wrote the book “The Gobi Desert”.

In the book “The Compensations of Plunder: How China Lost Its Treasures”, Justin Jacobs argues that the presence of priceless Chinese art and antiquities in Western museum wasn’t, as is often assumed, the inevitable result of Western imperialist deception and plunder. According to a review in the Los Angeles Review of Books, “most Chinese knew exactly what the foreign archaeologist was doing and how he was doing it. Not only that, but they even went so far as to provide voluntary and enthusiastic assistance to the exodus of treasures from China. The reasons why they did so have been lost to history, obscured by nationalist narratives of cultural sovereignty that were not shared by most Chinese in the early 20th century. This book reconstructs the original political, cultural, and economic context of the late Qing and early Republican eras that surrounded these expeditions and, in doing so, explains how China really lost its treasures. [Source: China Channel, Los Angeles Review of Books, August 5, 2020; Book: “The Compensations of Plunder: How China Lost Its Treasures” by Justin Jacobs (University of Chicago Press, July 2020)]

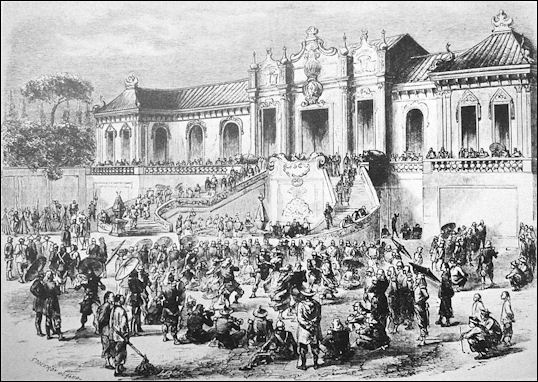

Looting of the Summer Palace by Europeans in 1860

In October 1860, after the Second Opium War officially ended, French and British troops went on the rampage and looted and burned down the Emperor's spectacular Summer Palace, known in Chinese as Yuanmingyuan ("Garden of Perfect Brightness"), near Beijing. Every schoolchild in China knows the story as a symbol of the humiliation exacted on China by the colonial powers. British-French forces razed the palace in retaliation for the execution of allied prisoners. After watching the looting of the Summer Palace, Captain Charles Gordon of the British army wrote, "You can scarcely imagine the beauty and magnificence of the palaces we burnt."

Recounted in Chinese textbooks and in countless television dramas, the destruction of the Old Summer Palace, remains a crucial event epitomizing China’s fall from greatness. Begun in the early 18th century and expanded over the course of 150 years, the palace was a wonderland of artificial hills and lakes, and so many ornate wooden structures that it took 3,000 troops three days to burn them down. The wound is still open and hurts every time you probe it, said Liu Yang, a Beijing lawyer and a driving force in the movement to regain stolen antiquities. It reminds people what may come when we are too weak. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, December 12, 2009]

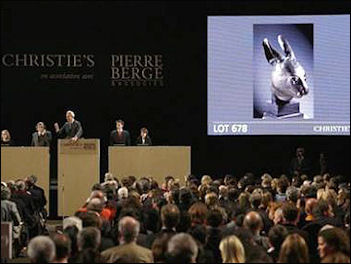

A number of antiquities and valuable pieces of art were stolen from the Summer Palace when it was razed by French and British troops. The most famous stolen antiquities are bronze animal heads, which date to 1750 and were part of a 12-animal water-clock fountain configured around the Chinese zodiac in the imperial gardens of the Summer Palace. As of the 2000s, seven of the 12 fountain pieces had been found; the whereabouts of the other five bronze heads are unknown. In March 2008, a big deal was made about the offering of a bronze rabbit’s head and a companion piece depicting a rat that were put up for sale at a Christies auction. The pieces had been stolen from the Summer Palace in 1860. They were owned by the late fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent.

Looting of the Summer Palace

Looting the Qing Imperial Tombs by Chinese in the 1920s

After the fall of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and because factions from the Revolution of 1911 could not agree, separationist warlord regimes fought ceaseless wars against one another. In the chaos of war, grave robbers were very active. Tomb guards left by former Qing governments no longer had wages, so they often stole, or helped to steal, what they were guarding. Trucks full of cultural relics stolen from mausoleums were common sights on the roads of Jixian County at that time. Under the rule of warlord Zhang Zuolin in Northeast China, the time saw so much was stolen that even most trees in the mausoleum areas were felled. [Source: China.org]

In 1928, such a large scale grave robbing operation occurred that almost all the underground funeral objects of the Huifeiling, Yuling Mausoleum and Putuoyu East Dingling disappeared. On June 12 of that year, Ma Futian, Regimental Commander in the 28th Army of Zhang Zuolin quietly occupied Malanyu. Sun Dianying, another warlord, however, ordered Tan Wenjiang, one of his military leaders to capture the tomb area. At dawn on July 2, Ma Futian was driven away and Tan's army looted the mausoleums in Malanyu. After that, Sun's army went straight to the area of Qing East Tombs, pretending to engage in war exercises in the area.

Tan Wenjiang placed policemen all around, denying access to the area and signs declared the army was "protecting the Tombs" to reassure the way. At midnight the engineering corps blew up the entrance, opening the passage leading to the underground palace. The stone door was pried open to give access to the rear room of the grave. Then Sun Dianying gave first priority to officers above battalion commander level to collect treasure for themselves. Finally, ordinary soldiers were allowed to take the leftovers.

The robbers first took the large treasure objects placed around the remains of Ci Xi, such as jadeite watermelons, grasshoppers and vegetables, jade lotus and coral. They even grabbed objects found beneath the body and ravaged the corpse itself, taking her imperial robe; tearing off her under clothing, shoes and socks, and taking all the pearls and jewels on her body. They even pried open Ci Xi's jaws and took the scarce pearl from her mouth. Finally they looted the objects under the coffin which had been favorites of Ci Xi when she was alive.

While Tan Wenjiang was robbing Ci Xi's tomb, Han Dabao, Brigade Commander under Sun Dianying led another army to Yuling Mausoleum and declared his intention to conduct war exercise. They blew the entrance of the underground palace, struck through the first, second, third and fourth stone doors and rushed into the rear room of the tomb. The coffins of Emperor Qian Long and his two empresses and three concubines were pried open: all the valuables from these coffins were looted and the skeletons thrown into the mud.

The looting operation was directed by Sun Dianying, who inspected from his car. When a truck had been filled with the valuable booty, the army fled quickly. The soldiers then rushed to Yuling Mausoleum and the underground palace of Putuoyu East Dingling and looted what they could.

Finally, local riffraff snuck into the two underground palaces to pick up leftovers. This kind looting left nothing in those two mausoleums except broken coffins; an inestimable lost. Newspapers reported the grave robbing and the news spread throughout China and around the world. People were outraged. Emperor Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi, who had dismissed Sun from his post, sent telegrams to Chiang Kai-shek; Yan Xishan, Commander of Garrison Force in Beijing; the Central Committee of Kuomintang, and local newspapers asking them to punish Sun Dianying severely. Many others also called for punishment. However, Sun Dianying bribed those who were in a position to discipline him and nothing was done.

Hunt in Foreign Museums for Art Treasures Taken From China

looted Summer Palace head

In late 2009, a delegation of Chinese cultural experts swept through American institutions, seeking to reclaim items once ensconced at the Old Summer Palace in Beijing, which was one of the world’s most richly appointed imperial residences until British and French troops plundered it in 1860. The delegation visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York with a crew from China’s national broadcaster filming the visit and fired off questions about the provenance of objects on display and requested documentation on a collection of jade pieces to show that the pieces had been acquired legally...But when nothing out-of-order was discovered the Chinese posed for a group photo and left.[Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, December 12, 2009]

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “Emboldened by newfound wealth, China has been on a noisy campaign to reclaim relics that disappeared during its so-called century of humiliation, the period between 1842 and 1945 when foreign powers subjugated China through military incursions and onerous treaties. But the quest, fueled by national pride, has been quixotic, provoking fear at institutions overseas but in the end amounting to little more than a public relations show aimed at audiences back home.” Stoked by populist sentiment but carefully managed by the Communist Party, the drive to reclaim lost cultural property has so far been halting. While officials privately acknowledge there is scant legal basis for repatriation, their public statements suggest that they would use lawsuits, diplomatic pressure and shame to bring home looted objects — not unlike Italy, Greece and Egypt, which have sought, with some success, to recover antiquities in European and American museums.”

“The United States scouting tour — followed by visits to England, France and Japan — quickly turned into a spectacle sponsored by a Chinese liquor company. As for the eight-member delegation, a closer look revealed that most either were employed by the Chinese media or were from the palace museum’s propaganda department. But the 20-day spin through a dozen institutions has not been especially fruitful. Wu Jiabi, an archaeologist and the leader of the delegation, said that meaningful contacts were made but acknowledged that the group had not discovered illicit relics. The visit has had its share of mishaps. Not all the museums on the itinerary were prepared for the delegation. One stop, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Mo., was scrapped after the group realized the museum was in the Midwest, not in the Northeast.

The art experts whom the group met along the way offered consistent advice: the lion’s share of palace relics are in private hands, including those of collectors in Hong Kong, Taiwan and mainland China. The best thing would be to look through the catalogs of Sotheby’s and Christie’s, said a curator at the Metropolitan Museum.

Efforts to Sell the Bronze Heads from the Summer Palace

In March 2008, a big deal was made about the offering of a bronze rabbit’s head and a companion piece depicting a rat that were put up for sale at a Christies auction. The pieces had been stolen from the Summer Palace in Beijing, razed by French and British troops in 1860 described above. A Chinese bidder, art dealer Cai Mingchao, claimed the bronzes with a $40 million bid and then said he no intention of paying. Acting on behalf of a nongovernmental group whose aim is to repatriate looted art, Ming said he bid on the bronzes as a patriotic act. Christie’s had put the the objects up for auction even though Beijing called the auction “illegal” and warned Christies not to proceed with it. “I think any Chinese person would have stood up at that moment,” Cai said of his bid, made by telephone through Christie’s. “It was just that the opportunity came to me. I was merely fulfilling my responsibilities...On moral grounds, and as a way to protest the auction...I want to emphasize that the money won’t be paid.” “Cai said he did not have the money to pay for the two heads he bought. And it was unclear how he had been able to register as a qualified bidder. Kate Malin, a spokesperson for Christie’s in Hong Kong, said all potential bidders at major auctions are required to submit bank and credit information as part of a registration process. [Source: Mark Mcdonald, New York Times, March 2, 2009 ^^]

In April 2000, two of the 12 zodiac bronze animal heads — the ox and monkey — were put on sale in Hong Kong. They were both successfully bought by the Poly Group, a People's Liberation Army affiliated corporation and arms dealer based in Beijing, for $900,000 and $930,000respectively. At the time, critics questioned whether the bronze heads were worth such high prices and said Poly's bids might raise the price for other heads from the same collection. But a representative of Poly Group said the bronze heads were invaluable “national treasures” and that they hoped their move could cause the rest of the animal heads to surface for public sale. . More of them did soon appear at public auctions, and just a month after buying the the ox and monkey heads, Poly bought the tiger head at a public auction in Hong Kong, this time for HK$14 million. [Source: Wu Zhong, Asia Times, March 11, 2009]

“In 2003, the National Treasures Fund of China, a quasi-governmental group, brokered a deal that brought one of the bronze fountain pieces — a pig’s head — back to China. With about $1 million donated by Stanley Ho, the real estate and casino billionaire from Macao, the head was purchased from an American collector, according to an account by Xinhua, the official Chinese news agency. Ho bought another — a horse’s head — for $8.84 million at an auction run by Sotheby’s in 2007. He subsequently gave the piece to China Poly, which owns a museum where it displays the Qing Dynasty bronzes.” Niu Xianfeng, deputy director of the Lost Cultural Relics Recovery Program, said his group had tried to buy the rat and rabbit heads in 2003 but dropped the effort when the sellers, apparently representatives of Saint Laurent, who died in June 2009 , and Bergé, asked for $10 million for each head. ^^

Was the Chinese Government Involved in the Sabotaged Sale of the Looted Bronze Heads?

looted Summer Palace head

There was speculation that the sabotage of the auction had the backing of the Chinese government. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Qin Gang said Cai had acted without government approval, though he reiterated Beijing's position that the bronze heads should be returned to China. Chinese officials attending the NPC and CPPCC annual sessions were grilled by the media on the scandal. [Source: Wu Zhong, Asia Times, March 11, 2009]

Neither the Chinese government nor the general public made a fuss over Summer Place bronze head in Hong Kong auctions in 2000, 2003 and 2007. But Beijing and the Chinese public were indignant over the Paris sale. For one thing, the auction was like a slap in the face for China as the looting of Yuanming Yuan was carried out by French and British forces during the second Opium War in 1860. The Chinese people's anger at the sale was heightened by the poor state of Sino-French relations. Beijing was angry over a recent meeting between French President Nicolas Sarkozy and the Dalai Lama last December.

“For Chinese people, the looting and burning of Summer Palace is a shameful chapter of Chinese history, and the 12 bronze animal heads would be better classed as symbols of Chinese shame rather than “national treasures”. For, as many critics have pointed out, they are not so ancient when compared with other Chinese bronze relicts; nor are they really fine pieces of Chinese art, as they were in fact designed by Jesuit missionaries.”

Many Chinese were taken aback aback what Cai had done. On the Internet, criticism of Cai is more harsh. “You said you did this on behalf of the whole Chinese people? How could you ever say this? We did not authorize you to act on our behalf,” said one blogger. “You seem to want to become a national hero. But what you have done shames our nation,” said another.

Image Sources: Palace Museum in Taipei ; Want China Times, Shanghaiist, Xinhua, Christie's

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021