MOST EXPENSIVE CHINESE ART WORKS

Most expensive Chinese art works sold at auction:

1) Qi Baishi’s “Twelve Landscape Screens” (1925) is the most expensive Chinese painting ever sold at auction as of 2020. It was was sold for US$140.8 million at Poly Auction, Beijing in December 2017.

2) Wu Bin’s “Ten Views Of Lingbi Rock” (c. 1610) was sold for US$77 million at Poly Auction, Beijing in October 2020. It consists of ten detailed drawings of a single stone.

3) Zao Wou-Ki’s “Juin-Octobre” 1985 (1985) was sold for US$65.8 million at Sotheby’s, Hong Kong in September 2018.

4) Huang Tingjian’s “Di Zhu Ming”(1045-1105) was sold for US$62.8 million via the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York at Poly Auction, Beijing in June 2010. It is a huge hand scroll with calligraphy. [Source: Mia Forbes thecollector.com, January 2, 2021]

5) Su Shi’s “Wood and Rock” (1037-1101) was sold for US$59.7 million at at Christie’s, Hong in November 2018. Su Shi’s elegant handscroll with paintings and calligraphy is from the Song Dynasty (960–1279)

6) Qi Baishi’s “Eagle Standing On Pine Tree” (1946) sold for $65.5 million at the China Guardian Spring Auction in Beijing in May 2011.

7) Huang Binhong’s “Yellow Mountain” (1955) was sold for US$50.6 million at the at China Guardian 2017 Spring Auctions. The work highlights Huang’s use of both ink and color.

8) Chen Rong’s “Six Dragons” (13th Century) was sold for US$49 million at Christie’s in New in March 2017. It was sold by the Fujita Museum. The scroll exceeded all expectations at Christie’s, selling for well over 20 times its estimate.

9) “Imperial Embroidered Silk Thangka” 1402-24) was sold for US$44 million at Christie’s in Hong Kong in November 2014. The ornate Tibetan silk thangka is remarkably well-preserved for an object of this age.

10) Pan Tianshou’s “View From The Peak” (1963) was sold for US$41 million at the at China Guardian 2018 Autumn Auctions. The work displays the painter’s skill with brush and ink.

11) Zhao Mengfu’s “Letters” (Ca. 1300) was sold for US$38.2 million at the China Guardian Autumn Auctions. It is a beautiful by one of the great masters of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368)

As a yardstick for comparison the most expensive painting sold internationally are:

1) $450.3million for “Salvator Mundi” (c.1500) by Leonardo da Vinci, sold in November 2017 at Christie's, New York

2) $300 million for “Interchange” (1955) by Willem de Kooning, sold in September 2015 through a Private sale

3) $250 million for “The Card Players”(1893) by Paul Cézanne in April 2011through a private sale

4) $210 million for “Nafea Faa Ipoipo” (When Will You Marry?) (1892) By Paul Gauguin in September 2014 through a Private sale

5) $200 million for Number 17A (1948) by Jackson Pollock, sold in September 2015 through a Private sale.

See Separate Articles: 20TH CENTURY CHINESE ARTISTS: QI BAISHI ZHANG, DAQIAN AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com ; MAO ERA ART factsanddetails.com ; MODERN ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE MODERN ARTISTS: CAI GUO-QIANG, ZENG FANZHI, WANG GUANGYI AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com ; AI WEI WEI: HIS LIFE, ART AND POLITICAL ACTIVITIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SHOCK ART, BODY PARTS, PHOTOGRAPHERS AND VIDEO AND GRAFFITI ARTISTS factsanddetails.com ; LOOTING CHINESE ART AND ARTIFACTS AND TRYING TO GET THEM BACK factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART MARKET: COLLECTORS, AUCTIONS, HISTORY, PROFITS AND BRIBERY factsanddetails.com ; FORGING, BREAKING AND COPYING CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Art Scene China Art Scene China ; Artron en.artron.net ; Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk ; Graphic Arts washington.edu ; Yishu Journal yishujournal.com ; Asia Society asiasociety.org ; Art in Beijing Factory 798 in Beijing Wikipedia Wikipedia; Communist China Posters Landsberger Posters ; More Posters chinaposters.org ; More Posters still Ann Tompkins and Lincoln Cushing Collection ; Chinese Modern Artists Cai Guo Qiang.com caiguoqiang.com Guggenheim Show guggenheim.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Zhang Xiaogang Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk Wikipedia article ; Wikipedia ; Various works artnet.de ; Yue Minjun Works artnet.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “A Modern History of China's Art Market” by Kejia Wu Amazon.com; “Chinese Antiquities: An Introduction to the Art Market (Handbooks in International Art Business) by Audrey Wang Amazon.com; “Collecting Chinese Art” by Sam Bernstein Amazon.com; “Collecting Chinese Art: Interpretation and Display” by Stacey Pierson Amazon.com; “Private Passions: Connoisseurship in Collecting Chinese Art” by Sam Bernstein Amazon.com; “The Compensations of Plunder: How China Lost Its Treasures” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com ;

Two Qi Baishi Works Sell for Over US$215 Million

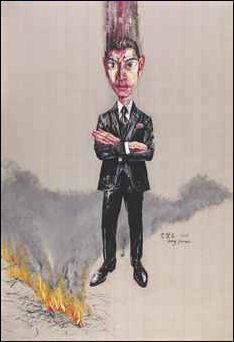

Zeng Fanzho work

auctioned by Christie's

Qi Baishi, “Twelve Landscape Screens” (1925) is the most expensive Chinese painting ever sold at auction as of 2020. It was was sold for US$140.8 million at Poly Auction, Beijing in December 2017. Mia Forbes wrote in thecollector.com: The work is a series of ink landscapes Mia Forbes wrote in thecollector.com: “The twelve screens, which show distinct yet cohesive landscapes, uniform in size and style but different in precise subject matter, epitomize the Chinese interpretation of beauty. Accompanied by intricate calligraphy, Wu’s paintings embody the power of nature while conjuring a feeling of tranquility. He produced only one other work of this sort, another set of twelve landscape screens made for a Sichuan military commander seven years later, making this version even more valuable. [Source: Mia Forbes thecollector.com, January 2, 2021]

Qi Baishi (1864-1957)is regarded as one of the greatest contemporary painters in China. He was influenced by Western styles but is considered by some to be the last great traditional painter of China. He painted a variety of subjects and was praised for the “freshness and spontaneity that he brought to the familiar genres of birds and flowers, insects and grasses, hermit-scholars and landscapes”. In 1953, four years before his death, Qi Baishi was elected president of the Association of Chinese Artists. In 2008 a crater on Mercury was named after him. “Eagle Standing on Pine Tree” is regared as Qi Baishi’s masterpiece. Among his other famous paintings are “Shrimp” and “Plum Blossom.”

In May 2011, Qi Baishi’s painting “Eagle Standing on Pine Tree”sold for $65.5 million..T he Global Times reported: “An ink-wash painting by Chinese painting master Qi Baishi was sold for 425.5 million yuan ($65.5 million) during the Guardian Spring Auction at the Beijing International Hotel Convention Center. The auction started with a price of 88 million yuan ($13.5 million) and was sealed with the record price for modern and contemporary Chinese art work after more than 30 minutes of bidding. As one of the largest paintings in Qi's oeuvre, it measures 100 centimeters by 266 centimeters, with the calligraphy couplet engraved within measuring 65.8 centimeters by 264.5 centimeters. The couplet reads "A Long Life, A Peaceful World." Another piece of Qi's work was also sold for 80 million yuan ($12.3 million) at the auction. [Source: Global Times, May 23, 2011]

Qi Baishi’s “Eagle Standing On Pine Tree” (1946) was 6th most expensive work of Chinese art ever purchased as of 2020. It was bought by Hunan TV & Broadcast Intermediary Co and sold by Chinese billionaire investor and art collector, Liu Yiqian. The purchase set off a controversy. After the gavel came down the top bidder refused to pay on the grounds that the painting was a fake. Mia Forbes wrote in thecollector.com: “As well as causing chaos for China Guardian, on whose website no trace of the painting can now be found, the controversy highlighted the ongoing problem with forgery in the emergent Chinese market.The issue is exacerbated in the case of Qi Baishi by the fact that he is thought to have produced between 8,000 and 15,000 individual works during his busy career. [Source:Mia Forbes thecollector.com, January 2, 2021]

Su Shi Scroll Sells For Nearly US$60 Million

Yang Shaobin work

auctioned by Christie's

Su Shi’s “Wood and Rock” (1037-1101) is fifth the most expensive Chinese work of art ever sold at auction as of 2020. One of only two works by 11th-century artist known to exist, it was sold for US$59.7 million at at Christie’s, Hong in November 2018. Su Shi’s elegant handscroll with paintings and calligraphy is from the Song Dynasty (960–1279). Measuring 28 centimeters high, and 51 centimeters wide, this ink-on-paper work depicts a gnarled, leafless tree and a rock behind from which a few young bamboo shoots emerge. [Source: Mia Forbes thecollector.com, January 2, 2021]

Mia Forbes wrote in thecollector.com: One of the scholar officials charged with the administration of the Song Empire, Su Shi was a statesman and a diplomat as well as a great artist, a master of prose, an accomplished poet and a fine calligrapher. It is partly for the multi-faceted and highly influential nature of his career that his remaining artwork is so valuable. ‘Wood and Rock’ is an ink painting on a handscroll over five meters in length. It depicts a strangely shaped rock and tree, which together resemble a living creature. Su Shi’s painting is complemented by calligraphy by several other artists and calligraphers of the Song Dynasty, including the renowned Mi Fu. Their words reflect on the meaning of the image, speaking of the passing of time, the power of nature and force of Tao.

Frederik Balfour of Bloomberg wrote: “The work is only one of two known scrolls produced by Su Shi, and the first to ever appear at auction, Christie’s said. The other resides in the National Palace Museum in Taiwan. "This is simply the best Chinese painting you could possibly get," said Jonathan Stone, co-chairman of Christie’s Asian Art department, who likened the piece’s significance and rarity to that of "Salvator Mundi" by Leonardo Da Vinci. "In the purely market sense, there is comparability." [Source: Frederik Balfour, Bloomberg, August 30, 2018]

Su Shi, a household name in China, was an 11th-century scholar, statesman, poet, writer, calligrapher and artist, whose painting style has influenced virtually every Chinese painter ever since, according to Kim Yu, Christie’s international senior specialist of Chinese paintings. “He began an "aesthetic revolution" that departed from the highly detailed and meticulous academic Song dynasty works, which required months to complete. Su Shi’s "Wood and Rock" is a simple and spontaneous work created for the artist’s personal pleasure and painted in one sitting, Yu said.

“Between the 11th and 16th century, four "colophons," or commentaries by famous calligraphers were added to the scroll, which now is more than six feet long. The scroll also contains 41 collector’s seals which provide an unimpeachable record of its ownership provenance. “Like Da Vinci, Su Shi was a "renaissance man," though long before the Western concept came into existence several centuries later, Stone said. "I like to think of Leonardo as a Western Su Shi, rather than Su Shi as a Chinese Leonardo. We shouldn’t look at things through an Atlantic lens," he said. The former owner was “a Japanese family that acquired it from a Chinese dealer in 1937. They contacted Christie’s about selling it after the success of a $263 million sale of Chinese artworks from the Fujita Museum it held in New York in March 2017.

Qing Dynasty Vase Sells for a World Record $41.6 Million

In 2021, a Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) vase sold for $41.6 million, a world record for Chinese ceramics. Antiques and the Arts Weekly reported: The world record for a Chinese ceramic has been reset at $41.6 million, which Poly Auctions realized on June 7. The intricate four-piece Imperial yangcai ruby ground with carved openwork “phoenix scene” revolving vase, was made during the Qianlong period (1736-1795). [Source: Antiques and the Arts Weekely, World June 22, 2021

The form features an outer shell as well as an interior vase, neck and cover, all parts requiring each element to be separately glazed, enameled and fired perfectly. Few revolving vases survive and, standing 24¾ inches tall, the example sold by Poly is only the second tallest known to survive.

The vase was not fresh to the market; it had crossed the block at Christie’s London in 1999 when it sold to Chinese art dealer William Chak, for $537,030. It subsequently sold to an Asian collector, who was the one selling it through Poly Auctions. The previous world record for Chinese ceramic was $37.7 million, which was achieved for a Northern Song dynasty (907-1127) Ru Guanyao brush washer by Sotheby’s Hong Kong in April, 2017. In 2010, $32.4 million was paid for a Qing double-gourd vase.

Ming Dynasty "Chicken Cup" Sell for $36.3 Million

In 2014 a Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) "Chicken Cup" sold for for $36 million. James Pomfret of Reuters wrote: “A rare wine cup fired in the imperial kilns of China's Ming dynasty more than 500 years ago sold for HK$281.2 million (US$36,3 million) at a Sotheby's sale in Hong Kong, making it one of the most expensive Chinese cultural relics ever auctioned. The tiny porcelain cup from the Chenghua period, dating from 1465 to 1487, is painted with cocks, hens and chicks, and known simply as a 'chicken cup'. It is considered one of the most sought-after items in Chinese art, viewed with a reverence perhaps equivalent to that for the jewelled Faberge eggs of Tsarist Russia. "Every time a chicken cup comes up on the market, it totally redefines prices in the field of Chinese art," said Nicolas Chow, deputy chairman of Sotheby's Asia, after the sale. The last time a similar chicken cup was auctioned, in 1999, it fetched HK$29 million, around a tenth of the 2014 price.[Source: James Pomfret, Reuters, April 8, 2014]

“With just 16 known Chenghua chicken cups surviving to the present day, most in public museums, only a handful have ever come to auction. Only four of these remain in private hands. Prized by Chinese emperors and afficionados through the centuries for their quality, rarity and legendary silky texture, Chenghua chicken cups fired in the imperial kilns of Jingdezhen are among the most prized, and forged, objects in Chinese art.

“In a packed auction hall, bidding for the delicate, palm-sized cup began at HK$160 million and drew steady bids from three parties, before being eventually sold to major Chinese collector Liu Yiqian for a bid of HK$250 million. The final price of HK$281.2 million, including fees, was a new world auction record for any Chinese porcelain.

“The cup had come from the celebrated Western collection of Chinese ceramics, the 'Meiyintang', accumulated over half a century by Swiss pharmaceutical tycoons the Zuellig brothers. With the purchase by Liu, a Shanghai-based billionaire with his own private 'Long Museum', the Meiyintang centrepiece is expected to become the only known genuine chicken cup in China. “"The price was OK, not so high, not so low," said Robert Chang, a leading collector based in Hong Kong. Some experts said China's slowing economy and credit squeeze may have sapped some market enthusiasm for the chicken cup, with the price falling just short of its high estimate. "There were not as many bidders, which was kind of surprising," said Richard Littleton, a Western dealer at the sale. "Where is all this big Chinese money we were expecting to see?"

Liu Yiqian paid for the cup with an American Express card and then proceeded to shock everyone by celebrating his new purchase by sipping some tea from it. The Wall Street Journal reported: “Mr. Liu bought his cup in a heated Hong Kong Sotheby’s bidding war that lasted seven minutes. When he paid up — by swiping his American Express card an individual 24 times, according to Sotheby’s — he also decided to take a celebratory swig from the cup. Images of Mr. Liu sipping from the cup circulated over the Internet this weekend, sparking fast condemnation from Chinese observers online. “You think you can drink it and become immortal? Or that it will extend your life? In fact, isn’t it just a way to satisfy your vanity?” wrote one Weibo user. “Sigh, Chinese people are just like this,” opined another: “No people who are civilized would treat a cultural treasure like this. No wonder Chinese people are looked down on by other countries’ citizens.” [Source: Te-Ping Chen and Olivia Geng. Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2014]

Mr. Liu told China Real Time that he wasn’t trying to show off his wealth. “It happened when I was paying,” said Mr. Liu, who made his fortune in finance. “A Sotheby’s staffer poured me some tea. I saw the [chicken cup] and excitedly poured some of that tea into the cup and drank a little,” he said. “Such a simple thing — what’s so crazy about that?” “Emperor Qianlong has used it, now I’ve used it,” said Mr. Liu of his chicken cup, referring to one of the Qing Dynasty’s most celebrated emperors. “I just wanted to see how it felt.” The cup, he added, “isn’t a commercial product appropriate for the masses.” Online, some said Mr. Liu should be left alone. “The money that people have strived to earn all their lives, they’re just spending in search for some happiness. What’s it got to do with you?”

Modigliani Painting Sold for $170 Million to Same Buyer as the Chicken Cup

In November 2015, Liu Yiqian, a former taxi driver turned billionaire art collector, who bought the chicken cup described above, bought a painting of a nude woman by Amedeo Modigliani for $170.4 million at an auction at Christie’s in New York. Liu said he planned to bring the work back to Beijing, where he and his wife have two private museums. ““We are planning to exhibit it for the museum’s fifth anniversary,” he said. “It will be an opportunity for Chinese art lovers to see good artworks without having to leave the country, which is one of the main reasons why we founded the museums.”[Source: Amy Qin, New York Times, November 10, 2015]

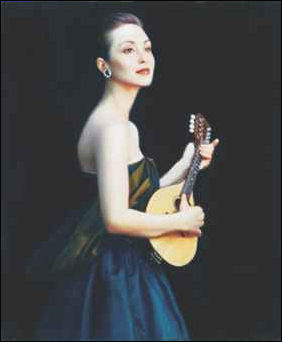

Chen Yifei work

auctioned by Christie's

Amy Qin wrote in the New York Times: “Bidding by telephone, Mr. Liu, 52, was one of six people competing for Modigliani’s 1917-18 canvas, “Nu Couché,” during the auction. The final price of $170.4 million with fees was well above the previous auction record of $70.7 million for a work by Modigliani. With Mr. Liu’s winning bid, the painting became the 10th work of art to reach the elite nine-figure club for works sold at auction. “Modigliani’s works already have a pretty established value on the market,” Mr. Liu said. “This work is relatively nice compared to his other nude paintings. And his nude paintings have been collected by some of the world’s top museums.”

“As a teenager growing up in Shanghai during the tumultuous years of the Cultural Revolution, Mr. Liu sold handbags on the street and later worked as a taxi driver. After dropping out of middle school, he went on to ride the wave of China’s economic opening and reform, making a fortune through stock trading in real estate and pharmaceuticals in the 1980s and 1990s. According to the 2015 Bloomberg Billionaires Index, Mr. Liu is worth at least $1.5 billion. “To me, art collecting is primarily a process of learning about art,” Mr. Liu said in an interview with The New York Times in 2013. “First you must be fond of the art. Then you can have an understanding of it.”

“Mr. Liu, together with his wife, Wang Wei, is one of China’s most visible some say flashy — art collectors. Over the years, they have built a vast collection of both traditional and contemporary Chinese art, much of which is displayed in their two museums in Shanghai: the Long Museum Pudong, which opened in 2012; and the Long Museum West Bund, which opened in 2014. Ms. Wang, 52, is the director of both museums.

“The couple’s collection includes a 15th-century silk hanging, called a thangka, bought by Mr. Liu for $45 million at a Christie’s auction in Hong Kong last year. The purchase made headlines when it set the record for a Chinese artwork sold at an international auction. Mr. Liu reportedly paid for the Modigliani with an American Express credit card, earning him many millions of reward points.

Record Prices for Traditional Chinese Art and Calligraphy in 2010

At the 2010, spring sales draw a number of ancient Chinese paintings and calligraphy works were sold for record prices. Several pieces fetched more than 100 million yuan ($18 million) each at sales hosted by domestic auction giants Beijing Poly, China Guardian and Beijing Hanhai, with one reaching 436.8 million yuan ($63.8 million). Apart from the astronomically-high sales, a large number of works went for around the 20-million-yuan ($2.94 million) mark. [Source: Wu Ziru, Global Times, June 2, 2010]

“This is an all-ascending market that you could have hardly imagined before,” Zhao Li, professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, told the Global Times. “Collectors and investors just keep bidding, as long as there is a rare piece.” “It used to be beyond our imagination that a piece of Chinese work, no matter how precious it is, could be sold for hundreds of millions of yuan,” commented Hu Jiaojiao, vice director of China Guardian. “Things are changing so fast today. Now we are confident that the market is sound and healthy, with so many collectors interested in classic paintings and calligraphic works.”

Hand scroll Dizhuming by poet and calligrapher Huang Tingjian from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) was one of the most hotly pursued items. It finally sold for 436.8 million yuan at Poly's spring sales to an undisclosed buyer, the price far beyond the expectations from both the auction house and collectors alike.

The sale set a new record for any genre of Chinese work - from antiques to contemporary pieces, almost doubling the previous high of 230 million yuan ($34 million) for a piece of blue and white porcelain from the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368), which sold at Christie's in London five years ago.

The 15-meter-long calligraphic hand scroll, Dizhuming, was completed in 1095. The original length of the hand scroll was 8.24 meters, but was then extended to 15 meters over the span of 800 years as its collectors, including prominent ancient Chinese scholars and royal court officials, added additional inscriptions to the piece.

Six Chinese classic paintings and calligraphic works each selling for over 100 million yuan. Temple in Mountains in Autumn, a landscape painting by Yuan Dynasty artist Wang Meng was sold for 136.64 million yuan ($20.1 million). Hand scroll painting Mount Yandang by Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) painter Qian Weicheng went under the hammer for 129.92 million yuan ($20 million), five times its former record price of 24.08 million yuan ($3.5 million) at China Guardian's 2007 spring auctions.

In March 2011, at the auction house Lebarbe, in Toulouse, France, a Chinese buyer set a new French record for Chinese art with a $31 million bid on a scroll painting from the Imperial Palace in Beijing.

Chinese collectors are buying up works by artists that few Westerners have heard of. In May 2011, the Global Times reported: “An ink-wash painting by Chinese painting master Qi Baishi (1864-1957) was sold for 425.5 million yuan ($65.5 million) during the Guardian Spring Auction at the Beijing International Hotel Convention Center Sunday night. The auction started with a price of 88 million yuan ($13.5 million) and was sealed with the record price for modern and contemporary Chinese art work after more than 30 minutes of bidding. As one of the largest paintings in Qi's oeuvre, it measures 100 centimeters by 266 centimeters, with the calligraphy couplet engraved within measuring 65.8 centimeters by 264.5 centimeters. The couplet reads "A Long Life, A Peaceful World." Another piece of Qi's work was also sold for 80 million yuan ($12.3 million) at the auction. [Source: Global Times, May 23, 2011]

Not only people from auction houses, but also many experts see the record-breaking prices as a good thing for the Chinese art market, saying there is still a large gap to be filled in terms of catching up with the international scene.

$81 Million Chinese Vase That Nobody Paid For

At the Ruslip auction house in Bainbridge in northeast London a Qianlong-era porcelain vase from China was sold at the staggering $81.5 million in November 2010, beating previous records for Chinese ceramics ($32 million) and Asian art ($62 million). For the elderly woman and her son who auctioned off the vase — which was kept on a bookcase by the woman’s brother in law and insured for $1,400 — it was like winning the lottery. Experts in the Asian art field were shocked. London art dealer Daniel Eskenazi told The Times of London, “It didn’t relate to anything else. That vase wasn’t worth double all previous works.” [Source: Times of London]

The price paid for the vase was nearly 50 times beyond its estimate of around $1.9 million. The colorful and intricately worked 18th porcelain century vase is of good enough quality it may have been kept in an imperial palace, perhaps the Qianlong Emperor himself. In the 1960s it was taken by the brother to the television show “Going for a Song” — a forerunner of “Antiques Roadhsow” and dismissed by a BBC as “a very clever reproduction.” It is not clear how the brother came in possession of it. Perhaps it is from a relative who traveled around the world between World War I and World War II.

The elderly woman inherited the vase when her brother died. David Reay, manger of Bainbridges, a small family-run auction house, told the Times of London, “The piece was sold by a 70-year-old woman. We were clearing her brother’s house after he died. I saw a few nice things: a lovely grandfather clock and some old books...Then a vase on top of the bookcase caught my eye. It was on a tall bookcase, It had been there for God knows how long. It was covered in dust, I looked at the vase and I said, “Oh, that looks nice. They told me it had been valued at 800 pounds two months earlier.”

Jane Macartney wrote in the Times of London: “Experts say that Qing porcelains are prized for their perfection. The Qing emperors, particularly Qianlong’s father, Yongzheng took a personal interest in all the creation of porcelain that would appeal to their aesthetic senses. The use of delicate powder enamels to create polychrome decorations was a difficult and time-consuming process. As many as 90 pieces out of 1000 could be smashed because they contained flaws. The creation of a single vase could involved with as many as 40 people.”

Shanghai art agent William Hanbury-Tenison told the Times of London the porcelain are prized not just for their scarcity: “The Chinese can say they exceed anything anyone in the world has ever done. They are a symbol of national technological prowess.” For a long time collectors sniffed at anything near from the Ming dynasty. Macartney wrote: “Porcelain thrown during the early years of the Qing dynasty were regarded as passable but anything lower was perceived as vulgar? Now however “the market is being revolutionized by the rising prosperity of Taiwan and China . New collectors are lured by the more ostentatious colors of pieces from emperors of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.”

The story of the $81 million vase though seems to have an unhappy ending. As of March 2011, the sellers had not been paid. Some suspect the buyer — thought to be a Beijing agent — has refused to pay on the grounds of cultural patriotism, the same rationale used after a 2009 auction to not pay for the bronze animal heads taken from the Summer Place.

Hong Kong Hotel Cleaners Mistakenly Throw Away $3.5 Million Painting

“Hong Kong hotel cleaners mistakenly threw away “Snowy Mountain” — a painting by Chinese artist Cui Ruzhuo that had just been sold at an auction for US$3.5 million. Umberto Bacchi wrote in the International Business Times: “Snowy Mountain” a 2012 ink wash painting by Cui Ruzhuo went under the hammer for US$3.5 million at an auction held at the five-star Grand Hyatt hotel in Hong Kong. “A day later it was reported missing to police by the auctioneers, Poly Auction. [Source: Umberto Bacchi, International Business Times, April 9, 2014]

“A Hong Kong police source told the South China Morning Post newspaper that CCTV images showed a hotel cleaner throwing the packed artwork atop a pile of rubbish. The source said police unsuccessfully searched a local landfill where the painting was likely to have been disposed. Police said they had not ruled out the possibility that the painting has been stolen, and were still treating its disappearance as a case of theft. No arrests have been made.

Gladis Young, director of communications at the hotel, said hotel staff were not responsible because auctioneers usually hired external staff. "It is the auction houses or third-party exhibitors that handle the installation and dismantling of their own exhibitions, whether by themselves or hiring a contractor," she told South China Morning Post. "The hotel is not responsible for the security of the exhibits."

Image Sources: 1) Palace Museum in Taipei ; Others Christie's, Sotheby's and Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021