CHINESE SHOCK ART

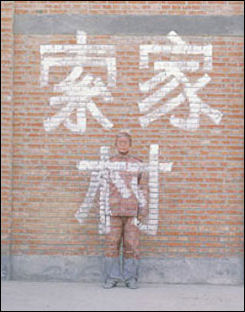

Tsang Tsou-choi with his work

Chinese artists are also grabbing headlines by roducing some of the world's most disgusting, shocking and extreme art. Many of the artist are graduates of Central Academy of Fine Art. Critics call the art empty and pointless and shock for shock's sake.

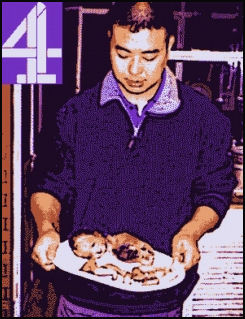

The performance artist Zhu Yu has displayed photographs of himself washing a stillborn baby and then eating dismembered body parts. He has had his own body parts grafted onto a pig. He describes his work an expression of the Christian faith, saying, “Jesus is always related It death, blood, wounds, etc.” On the point of shock art he said, "This is a numb society. So we need to scream. I wanted to experiment with the idea of wickedness. I wanted to show my distaste for all things civilized. I wanted to get to the bottom line."

One artist extracted human oil from a corpse and dumped it down a sink. Another made ink splotches on the Encyclopedia Britannica with his penis.One guy hung himself from a roof beam in a barn with blood dripping from a tube in his neck. Another emerged naked from the carcass of a cow. We can't forget the guy who strung some sparrows to his penis with some strings. The idea was that they were supposed to fly. They didn't. At birthday party for one their own, the artist who create these works get drunk, take off their clothes and drip paint on each other genitals and body parts.

Qiang Gao and Zhen Gao are famous artist brothers who are known best for for using images of Mao Zedong in unsettling sculptures, paintings and performance art, including one of Mao figures pointing fingers at Jesus Christ, and for portraits of hated figures of Hitler, Kim Jong Il, Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden when they were children. Gao Qiang told the Los Angeles Times, “I don’t consider myself a dissident at all, I never even think about this question, I just use art to express what I want to express.” The Chinese government may not share that opinion. Security forces have raided the brother’s exhibitions, confiscate their pieces, jailed their friends and shut off the electricity to their studio, They we denied passport and forbidden from leaving China for their first solo show in Los Angeles in September 2010.

“Zhang Dali's “Chinese Offspring” is a collection of naked humans hanging upside-down from the ceiling, representing the powerlessness of Chinese immigrant workers. Some look anguished, others desolate; all are helpless.” [Source: Lucy Farmer, More Intelligent Life, November 12, 2008]

See Separate Articles: MAO ERA ART factsanddetails.com ; MODERN ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE MODERN ARTISTS: CAI GUO-QIANG, ZENG FANZHI, WANG GUANGYI AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com ; AI WEI WEI: HIS LIFE, ART AND POLITICAL ACTIVITIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART MARKET: COLLECTORS, AUCTIONS, HISTORY, PROFITS AND BRIBERY factsanddetails.com ; FORGING, BREAKING AND COPYING CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com ; HIGH PRICES PAID FOR CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Art Scene China Art Scene China ; Artron en.artron.net ; Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk ; Graphic Arts washington.edu ; Yishu Journal yishujournal.com ; Asia Society asiasociety.org ; Art in Beijing Factory 798 in Beijing Wikipedia Wikipedia; Communist China Posters Landsberger Posters ; More Posters chinaposters.org ; More Posters still Ann Tompkins and Lincoln Cushing Collection ; Chinese Modern Artists Cai Guo Qiang.com caiguoqiang.com Guggenheim Show guggenheim.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Zhang Xiaogang Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk Wikipedia article ; Wikipedia ; Various works artnet.de ; Yue Minjun Works artnet.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Art of Contemporary China” by Jiang Jiehong Amazon.com; The Art of Modern China by Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen Amazon.com; “A Modern History of China's Art Market” by Kejia Wu Amazon.com; “Modern Art for a Modern China” by Yiyan Wang | Amazon.com; “From Mao's Art Soldier to Xi’s Cartoonist: Political Cartoons” by Shaomin Li Amazon.com; “Chinese Propaganda Posters” by Anchee Min and Stefan R. Landsberger Amazon.com; “Cultural Revolution and Revolutionary Culture” by Alessandro Russo Amazon.com; “The Art of Resistance: Painting by Candlelight in Mao's China” by Shelley Drake Hawks Amazon.com; “Art Mao: The Big Little Red Book of Maoist Art Since 1949" by Pia Copper and Francesca Dal Lago Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong’s “Talks at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Ar

Works by Modern Chinese Shock Artists

Work by Sheng Qi

The artist Pen Yu creates art from live animals. One of her most infamous pieces, Curtain, featured more that 1,000 frogs, grass snakes and lobsters, each pierced with a wire and strung up to die. On the piece Pen told Independent, "Yes, it's cruel. It's dangerous. It hurts. My art attacks the animals. The animals attack the viewer."

Sun Yuan makes installations with body parts and dead babies. One of his most sickening works, “Honey”, features a still-born fetus placed on top of the head of a dead old man. Another one of his works is made up of bloody spinal columns from dozens of sheep. Sun and Peng live together in an apartment-studio filled with pictures dead people and tortured animals.

Sheng Qi mutilates his body and then paints it. He first emerged in 1986, when he did a number of performance pieces that involved standing naked in the freezing cold at the Great Wall of China. In 1989, distraught over Tiananmen Square, he hacked off one fingers with a meat cleaver and now uses the stub as a paint brush. His performance piece, “Universal Happy Brand Chicken”, performed in London in the late 1990s, consisted of teh artist fondling and kissing four plucked chickens, slashing the dead birds with a knife and then urinating on them.

Xiao Yu makes ghoulish creatures with actual human heads, fish eyes, chicken wings and goose eyes. He sewed a the head of a human fetus on to the body of a sea gull to “provoke the viewer into reflecting on the absurdity of life.” The work was removed from an exhibit in Switzerland after museum-goers complained. Gu Wenda’s 10,000 Kilometers is a mini-replica of the Great Wall of China made entirely of bricks made of pressed human hair. The artist Gu Dexin displayed containers full of frozen animal brains and hearts.

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu are known for their works with cadavers. A piece shown at the Saatchi gallery in London features replicas of old people — toothless and disheveled and looking a lot like famous world leader — moving slowly around in motorized wheelchairs.

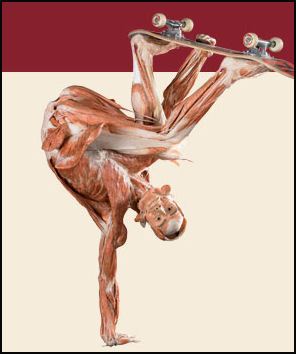

China: the Supplier of Parts for Body Art

In 1990s and 2000s, “Body Worlds” exhibitions — featuring "sculptures" made with skinless cadavers, dehydrated brains, tarred human lungs, and corpses posed like soccer players — were very popular at galleries and museums throughout the world. Some exhibitions attracted over 300,000 people, with people waiting three hours in line to see the works. As of 2006, the shows had been seen by 20 million people and taken in $200 million. The source of most of the bodies and the body parts for the “Body Worlds” exhibitions has been China — with suppliers centered around the eastern city of Dalian. Dr. Gunther von Hagens, the organizer of the exhibitions, told the New York Times that he came to China because there was easy access to bodies, cheap labor and few government regulations, “When I came here,” he said,” I was told, we’ll have no problems with Chinese bodies.” His Chinese partners told him “we can use unclaimed bodies...Now it’s difficult but then it was no problem at all.”

Body Worlds piece

Most of the businesses that deal in the body trade are a bit cagey when asked where the bodies come from. Some have been legally obtained from the Dalian Medical University. A spokesman for one company involved in the trade said these are unclaimed Chinese bodies that police have given to medical schools. Some are said to belong to mentally ill people or executed prisoners. In June 2006, police in Dandong, a city 150 miles northeast of Dalian, found 10 corpses in a farmers yard. The police said the bodies were being used by a firm financed by foreigners. Worried about the trade in illegal bodies, the Chinese government issued new regulations in July 2006 that outlawed the purchase or sale of human bodies and restricted the import and export of human specimens unless used in research,.

Body Worlds pieces have included livers and lungs damaged by alcohol and smoking, a female corpse cut open to reveal a five month old fetus, and a copse with all of its muscles and organs exposed and its skin draped like a coat over one arm. The bodies and organs have been preserved by "plasitnation"a process in which cell water is replaced by plastic by immersing body parts in acetone chilled to 13 degrees F. The procedure was invented by Dr. von Hagens, an anatomy lecturer at Heidelberg University, as "anatomical artwork."

Plasination preserves the shape and color of the body parts but give them a plastic-like appearance. The factories and work shops that prepare the bodies and body parts are in China. One employs 260 workers who process about 30 bodies a year. The workers, who get paid $200 to $400 a month first dissect the bodies, and remove the skin then place the bodies into machines that replace human fluid with soft chemical polymers.

Describing the workers at one such factory, David Barboza wrote in the New York Times: “Inside a series of unmarked buildings, hundreds of Chinese workers, some seated in assembly line formations, are cleaning, cutting, dissecting, preserving and re-engineering human corpses...In a large workshop called the positioning room, about 50 medical school graduates work with the dead, picking fat off the cadavers, placing them in seated or standing positions and forcing the corpses to do lifelike things such as hold a guitar or assume a balled position.”

Crickets, Cockroaches, Scorpions and Meat

Jane Perlez wrote in the New York Times: The signature work at “Art and China After 1989,” a highly anticipated show at the Guggenheim” in the fall of 2017 “was a simple table with a see-through dome shaped like the back of a tortoise. On the tabletop hundreds of insects and reptiles — gekkos, locusts, crickets, centipedes and cockroaches — mill about under the glow of an overhead lamp. During the three-month exhibition some creatures will be devoured; others may die of fatigue. The big ones will survive. From time to time, a New York City pet shop will replenish the menagerie with new bugs. [Source: Jane Perlez, New York Times, September 20, 2017]

“In its strange way, the piece, called “Theater of the World,” created in 1993 by the conceptual artist Huang Yong Ping.““Whether artists are Chinese or French is not important,” said Mr. Huang, who lives and works outside Paris. “I think the duty of the artist is to deconstruct the concept of nationality. There is going to be a day when there is no concept of nationality.” “Theater of the World” caused a stir in Vancouver in 2007 when Mr. Huang included scorpions and tarantulas; he withdrew the piece from the show there rather than comply with requests to remove those particular creatures.

Zhang Huan is a former performance artist who some years ago dressed himself in a suit made of slabs of carefully sculptured beef and paraded through the streets of New York City like Mr. America. The art critic Marc Glimcher said has the versatility of Rauschenberg. Mr. Zhang’s vast studio — a series of converted factories in the Shanghai suburbs — operates with about 100 workers who sand, carve and sculpture. They paint by sprinkling ashes onto a canvas and, following Mr. Zhang’s ideas, they stitch together giant dolls made from animal hides. Among his works are cowhide imprinted with a reverential image of Chairman Mao.

Peng Yu and Sun Yuan — the Bad Ass Couple of Chinese Art

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, a sculpting duo, are known for their satirical work. “Old People's Home” depicts a group of decrepit men, modeled to look like aged political figureheads, sit slumped in wheelchairs. Lucy Farmer wrote in More Intelligent Life: “The chairs slowly creep around the floor, occasionally nudging each other in an eerie game of slow-motion dodgems. Again the human likeness is uncanny, and the resemblances to men such as Yasser Arafat and Fidel Castro is both provocative and wickedly funny. As visitors stroll around the floor, noticing the lines of drool and stained uniforms, there are nervous giggles, evil sniggers and outbursts of hilarity. [Source:Lucy Farmer, More Intelligent Life, November 12, 2008]

Jane Perlez wrote in the New York Times: “They are known as the bad couple of China’s art. Peng Yu, 43, and Sun Yuan, 45, her husband, work in adjacent studios in Beijing’s thriving 798 Art District. Three heavy-duty motorcycles are parked outside Mr. Sun’s door. Inside, skeletons of a lion, a boar, a griffin and a few other animals decorate the shelves. Ms. Peng’s space is smaller, more spartan and contains a bare-bones kitchen. In 2000, they attracted attention with a performance piece, “Body Link,” at a show in Shanghai. Both artists took part in a transfusion of their own blood into the corpse of Siamese twins. The piece was created just after they decided to get married and was “a special kind of coming together,” Ms. Peng said. [Source: Jane Perlez, New York Times, September 20, 2017]

“Ms. Peng revels in her brazen politically incorrect attitudes. The couple’s work at the Guggenheim is one of their less radical pieces. The seven-minute video shows four pairs of American pit bulls tethered to eight wooden treadmills. The camera closes in on the animals as they face each other, running at high speed. The dogs are prevented from touching one another, a frustrating experience for animals trained to fight. The dogs get wearier and wearier, their muscles more and more prominent, and their mouths increasingly salivate. The piece was first shown with the actual dogs appearing before an audience at the Today Museum in Beijing in 2003. “The piece was so special, it stood out,” Ms. Peng said. “The art critics didn’t know what to say.”

Chinese Modern Photographer Artists

Tsung Leong photographs buildings torn down and replaced with tennis courts and apartment towers. Zhang Dali makes images of large heads in condemned buildings and then photographs them before they are torn down.

Zhao Liang did a series called “Social Survey” in which he photographed the reactions of people after he pulls out a fake gun on them. Cui Xiuwen placed a hidden camera in the women’s room at a high-class hostess bar and captured women shoving money in their cleavage and talking about money on their cell phones. Liu Wei has taken hundreds of close up of different body parts and recombined then using Photoshop so they look like ancient scrolls.

Wang Wei has had his art exhibited in London, Chicago and New York. He is known for his large-format photographs, often with a Coke or McDonald’s’s logo somewhere, that both celebrate and denounce “global” culture. His most famous pieces, China Mansion, feature female models acting out famous scenes from art history with orgies and feasts in the background. One of his video pieces features children endlessly repeating Maoist slogans.

Feng Li pokes fun at the Maoist era with a door-size "Big Red Book" with her picture on the cover. Xing Danwen did a piece called "Born in the Cultural Revolution" which features photographs of a naked, pregnant woman surrounded by Mao memorabilia. A Wang Jianwei exhibit featured a film showing Chinese people in various scenarios including a ping pong room, a court scene, a factory scene and a hospital scene where naked men were being weighed.

Wang Wusheng is a photographer honored with a United Nations exhibit in New York. He is best known for his images if Mt, Huangshan in eastern Aihui Province. His works evoke comparisons to Chinese landscape ink paintings. Trained as a physicist, he has been photographing the mountains for more than 30 years. Zhan Wang creates dreamy photographic images using the carved surface of a chrome “rock.”

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man

Liu Bolin is an artist-photographer born in 1973 in Shandong province. He graduated from Shandong Art Institute in 1995. He is well-known for making photographs of himself camouflaged in any environment. Each of his photos requires long hours of preparation, the longest being ten plus hours. He transforms himself into a painting canvas, and with his assistant’s help, he blends in with the background. [Source: Ministry of Tofu, January 29, 2011]

Liu said he tries to convey the message through his works: “Chinese artists are in a very difficult situation. The reason why I came up with this idea is many artists’ workshops were demolished forcibly. I wanted to create a series of photos titled “Hiding in the City” to protest in silence the adverse circumstances artists live in, the terrible attitudes the society takes towards art.” Can you find him in the following pictures? Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com http://photo.huanqiu.com/creativity/unlimited/2010-11/1254288.html

Zhang Peili and Chinese Video Artists

Zhang Peili is regarded as China’s first video artist. Jane Perlez wrote in the New York Times: A standout work by Zhang “shows a female newscaster on China’s state television, CCTV, repeating a meaningless screed about water. The woman, Xing Zhibin, with bouffant hair, and an expressionless middle-aged face from the 1980s and 1990s, was China’s Walter Cronkite. Mr. Zhang, 60, was shattered, he said, by the end of the democratic movement at Tiananmen Square. “That left a heavy influence on every Chinese person, and it lasts until today,” he said in his small apartment in Hangzhou. “He wanted to find a way to depict the absurdity of the state broadcaster never reporting the monumental event on the square. A friend of the artist contacted Ms. Xing and suggested that she read the definition of water many times over. “I lied and let my friend pass on the message that I was doing an education project about water,” he said. “I still don’t know if she knew that this video of her was actually used for a contemporary art piece.” [Source: Jane Perlez, New York Times, September 20, 2017]

Mr. Zhang is one of the most influential art teachers in China. He detects less political restlessness among the new generation of students, who are impressed by the new consumer-driven economy. Still, the huge gap between the rich and the not-so-rich in China is a recipe for future unrest, he said. But for the moment, he went on: “I procrastinate. Society is procrastinating. There is a lot to be done to change society but mostly we just skip it and wait.”

Wang Gongxin is a video artist who worked many year in Brooklyn, New York, where he was first turned on to video. Among his works are “It’s about Dream”, featuring 200 colorful mp4 screens with sleeping faces, and “Sky of Brooklyn”, a television monitor placed on three-meter-deep hole in his backyard in Beijing, showing a video of the Brooklyn sky .

Garbageman’s Graffiti Artist's Retrospective

A handful of graffiti artists are active in Beijing and other cities. Many of them have an interest in hip hop culture and seems to have been embraced it more as an art form than a means of political expression and rebellion. Luo Zhonglis of Sichuan Fine Arts Institute told the China Daily, “Graffiti art in China has gotten rid of the strong rebelliousness and confrontational attitude in Western graffiti.” Instead “it’s related to the aesthetics of people’s lives and leans more towards fashion.” Fear may be the primary reason the graffiti artists stay clear of politics. One artist in Xian told the China Daily, “There can’t be political themes, and if there are, they must be beneficial towards the government or the party.”

Invisible man Lu Bolin

hidden in graffiti Reporting from Hong Kong, Joyce Hor-chung Lau wrote in the New York Times, “A toothless garbageman who once wandered Hong Kong’s streets with dingy bags of ink and brushes tied to his crutches is now the subject of a major retrospective. About 300 calligraphic works by the late Tsang Tsou-choi — who is best known by his self-dubbed title, the King of Kowloon — are showing at the ArtisTree art space in a high glass tower.” “The show, “Memories of King Kowloon” in a spacious corporate-sponsored dimly lighted gallery, quiet as a library, would have been foreign territory for Mr. Tsang. He was most at home under the tropical sun and neon lights. An outsider artist, he spent half a century dodging security guards and police officers as he obsessively covered lampposts and mailboxes, slums and ferry piers, with his distinctive Chinese text.

[Source: Joyce Hor-chung Lau, New York Times, May 4, 2011]

“The colorful ink-on-paper pieces make up the best part of the ArtisTree retrospective. But there was little the organizers could do to replicate Mr. Tsang’s real legacy: his street art has been reduced to only four sites, including a single pillar now preserved at the old Star Ferry pier. Mr. Tsang’s work is supplemented with photographs, a documentary film, installations and pieces by other artists said to be inspired by Mr. Tsang. The presentation seems almost too slick for its subject. The space is dark and serious. Newspaper clippings and objects from Mr. Tsang’s apartment — a crushed Coke can, brushes, empty ink bottles — are displayed in light boxes, as if they were treasures. To show where Mr. Tsang’s works once existed, there is a glowing 3-D replica of Hong Kong’s skyline that looks like a property developer’s model.”

Mr. Tsang’s scribbles were once part of a messy but wonderfully human cityscape, and nostalgia for him has grown as modern complexes have replaced wet markets, family shops and streetside stalls. “Hong Kong has been tidied to the point that it no longer makes sense,” Joel Chung a fiend of Tsang told the New York Times. “It’s only tall glass buildings, where people go straight from the home to the metro to the mall, all in air-conditioned interiors.” Mr. Chung acknowledged the irony of having a King of Kowloon retrospective in a skyscraper. “Ideally, his art would be anywhere and everywhere, but it’s too late for that now,” he said. “People in the art world would probably not go seek out some graffiti in Mongkok anyway, so it’s good that we have a show here.”

Swire Properties’Island East complex, which is home to both ArtisTree and the offices of 300 multinationals, is a place of uniformed guards and immaculate lobbies, where nobody would dare litter, much less paint graffiti on a wall. Babby Fung, a spokeswoman for Swire, called Tsang a “cultural icon.” When asked how Swire would react to a modern-day King of Kowloon decorating its glass towers with ink, she replied, “We’re not focusing just on his graffiti. Instead, we’re seeing his as a part of Hong Kong history.” Pressed further, she added, “We’d communicate with him first to ascertain if he was really an artist.”

Graffiti Artist's Unique Story

Joyce Hor-chung Lau wrote in the New York Times, “Mr. Tsang, who died in 2007 at the age of 85, created an estimated 55,000 outdoor pieces, almost all of which have been washed away, painted over or torn down by the authorities and real estate developers. He was a rebel graffiti artist decades before it was fashionable, creating art brut in a city that has no time for outsiders.” [Source: Joyce Hor-chung Lau, New York Times, May 4, 2011]

“Mr. Tsang arrived in Hong Kong as a teenage refugee from Guangdong, a southern province bordering Hong Kong, in the 1930s, and began his urban painting in the 1950s. He toiled under the delusion that he was the rightful heir and ruler of the Kowloon Peninsula, dismissing all political factions that had controlled the area: the Qing Dynasty until 1898, the British until 1997 and China today. In his thick scrawl, he marked his territory with “royal decrees’and a “family tree,” using the names of his ancestors and eight children to build an imaginary web of princes and princesses. Intentionally or not, he tapped into the unease of a populace tossed between two governments. He defaced, with equal joy, Queen Elizabeth II’s insignia on colonial-era post boxes and campaign posters for Hong Kong politicians.”

His real-life wife and children shrank from attention when Mr. Tsang’s art became known, and even held a decoy funeral when he died to divert fans and the news media. “The way society saw him, as an insane person, caused his family to feel ashamed,” said Chung, a longtime friend of Mr. Tsang’s who lent hundreds of ink-on-paper works for the show. “He loved his family but, by figuring them so prominently in his work, he embarrassed them and, in their eyes, brought them down in society.” Mr. Chung, an artist and curator who teaches at a creative arts high school in Kowloon, told the New York Times that most of his students had been taught to shun Mr. Tsang for being mentally ill. “Generations of parents and grandparents have been pulling kids away from him on the street saying, “That man is dirty and crazy. Don’t go near him.”

Mr. Chung recounted meeting Mr. Tsang in the 1980s. “He was working at a busy intersection and the crowd around him was so great that I didn’t even see him at first,” he said. “There was this shirtless old man, sitting on a trash can, painting. I stood there transfixed for an hour, but he didn’t notice me until he ran out of ink and started hollering for more. He never said please. He was the king, and kings don’t have to say “please” to their subjects.” For years, Mr. Chung and others in the art scene bought him food and introduced him to writers and visiting artists.

Mr. Tsang’s entry into the mainstream was a 1997 exhibition at the Hong Kong Arts Centre, followed by a show at the 2003 Venice Biennale. In 2009, two years after he died, one of his pieces sold at an auction at Sotheby’s. Mr. Tsang, who began receiving disability and welfare payments when a falling garbage bin impaired both legs in 1987, never made a living from his art. “It earned him some pocket money, but it made no difference to him,” Mr. Chung said. “He just handed the cash over to his wife. Except for eating, sleeping and bathing — well, he didn’t bathe often — he was painting.”

Street Art in China as a Commercial Statement

Hannah Seligson wrote in the New York Times, “It isn’t the familiar Adidas look — that bold and basic three-stripe logo. Instead, it’s a design meant to evoke blowing wind, flowing water and flapping wings. The tricked-out design for new T-shirts in China was created by Chen Leiying, a 27-year-old artist known as Shadow Chen who lives in the coastal city of Ningbo. She is not even an employee of the company, but multinationals like Adidas are beginning to turn to young creative types like her to dream up images and logos for the under-30 set in China, a group that is 500 million strong.” [Source: Hannah Seligson, New York Times, April 30 2011]

“Call them China’s youth whisperers. From Harbin in the north to Guangzhou in the south, young artists, musicians and designers are being tapped to make companies’ brands cool. Like its counterparts elsewhere, this arty crowd sometimes looks and acts unconventional — but it’s not with political ends in mind. These young artists tend to set aside politics for commerce, and the promise of attractive paydays from foreign businesses.”

Adidas wants to be cool, “and the only way to be cool is to appeal to young people,” Jean-Pierre Roy, who until recently helped oversee product development in China for Adidas, told the New York Times. To help enhance that image, Adidas selected four Chinese artists, including Ms. Chen, to design 20 graphics for its new T-shirts.

Defne Ayas, an art history instructor at New York University in Shanghai, told the New York Times: “For some artists in this younger generation, the new political has become the “market.” They tend to be curious and friendly to the market; they don’t want to miss out on its opportunities.”

NeochaEdge and Making Money from Art as a Commercial Statement

Zhu Yu eats a baby

“At the center of this experiment is NeochaEdge, the first and only creative agency of its type in China,”Hannah Seligson wrote in the New York Times. “It was started in 2008 by two Americans, Sean Leow and Adam Schokora, to showcase the work of illustrators, graphic designers, animators, sound designers and musicians from across China. It now has 200 member-artists; NeochaEdge pays them per project to work on campaigns and product designs for brands like Nike, Absolut vodka and Sprite...Coca-Cola recently teamed up with it for a contest to find a young, creative type to put a Chinese spin on its American theme of “energizing refreshment.” The winner — or winners — will receive up to $65,000 in cash prizes and a trip to the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity.” [Source: Hannah Seligson, New York Times, April 30 2011]

Members of the agency have also produced a soundtrack and a streetlight graffiti show for Absolut, designed sneakers for the Jimmy Kicks shoe company and created content for an e-magazine for Nike about basketball culture in China. And by the end of this year, NeochaEdge will also become a virtual art gallery, selling artwork from its artists through its Web site.” The government is even starting to put its muscle behind companies like NeochaEdge. In Shanghai alone, the government has created more than 80 creative industry zones for 6,000 businesses. In 2008, the Shanghai municipal government named NeochaEdge as “one of the top representatives of the creative industry.”

“You can’t just stroll into China and see who is a hot artist,” says Roy told the New York Times. “It’s all still a little underground.” So Mr. Schokora, 30, and Mr. Leow, 29, have become trusted guides. “There are not many young Americans who speak fluent Mandarin and are as much at home talking to chief marketing officers as they are talking to graffiti artists in Guangzhou,” says Paul Ward, head of operations for Asia at the advertising agency Bartle Bogle Hegarty in Shanghai, which has collaborated with NeochaEdge, “They want to advance their careers, not challenge the political establishment,” Mr. Leow says. “Commercial art has rarely, if ever, contained dissent.”

In the early days of the the company,” Seligson wrote. “Mr. Schokora and Mr. Leow went searching for members at indie rock concerts, gallery openings and music festivals; now, however, the artists mostly come to them. Mr. Schokora says the company receives dozens of e-mails a day from young people all over China who want to be featured on the Web site, which also showcases work from artists who are not members of the consortium. Sometimes, artists even show up at the company’s office in the Jing An District in Shanghai without an appointment.”

“As well as playing matchmaker, NeochaEdge produces trend reports and a monthly e-magazine on the creative scene in the youth market. It also recruits for focus-group research, plans exhibitions and performances and holds workshops and training for artists. “We are a complement to advertising agencies,” Mr. Schokora told the New York Times. “If an advertising agency wanted an illustrator from, let’s say, Harbin, it would be pretty easy to search the database and find their portfolio online,” he says, referring to the capital of Heilongjiang Province in northeastern China. “Then we just hop on instant message and get in touch.”

Guo Jian and His Unsettling Diorama of Tiananmen Square Under Attack

Guo Jian is Chinese-born artist and Australian citizen. Didi Kirsten Tatlow wrote in the New York Times, “As an artist, Mr. Guo both actively and unconsciously reflects his surroundings, often via symbols. He said he had no wish to see China plunged into chaos. Yet he is drawn to probe boundaries, and the square’s apparent untouchability, he said, symbolizes the state’s desire for untouchable power.”

Guo has produced an unsettling diorama of Tiananmen Square under attack from helicopters with heavy machinery digging up the square. “In his taboo-shattering diorama,” Tatlow wrote, “this most powerful symbol of Communist Party rule — with its Mao Zedong mausoleum and portrait, its revolutionary monuments and Great Hall of the People — is under assault from all sides.

“In China you can knock down everything, just not Tiananmen Square,” said Mr. Guo. But, “If you have that attitude, then in the end, people will knock down your power.” Because a government intent on maintaining absolute power will eventually generate too much antipathy to endure. “And that’s the cycle of Chinese history,” he said. The diorama, which has not been publicly exhibited, is in his Beijing studio.

In Mr. Guo’s diorama, a 4.6-by-2.2 meter, or 15-by-7 foot, work in progress, toy trucks and diggers balance on piles of “granite” debris, actually Styrofoam. The roof of Mao’s mausoleum is caved in. The Forbidden City’s Gate of Heavenly Peace and the new National Museum of China show damage from both the wrecker’s ball and gunfire. Trees lie felled. Smoke billows.

The diorama plays specifically on the sensitive issue of government land seizures and property demolitions. Tens of millions of farmers and urban residents have lost their homes in the last three decades, forced out by local officials in league with developers. Earth-moving machines and trucks are a common sight in China. But why the attack helicopters? “Doesn’t “chai” look like warfare?” asked Mr. Guo, using the Chinese word for demolition. “Places that have been “chaied” look like battlefields.” Why the giant Ferris wheel, tilting at the edge of the square” “Everything in China today is entertainment, even destruction,” he said. “People gather and say, “Wow, that was knocked down really well.” So why not have fun watching Tiananmen Square being chaied, too?”

Zhang Runshi

Zhang Runshi is known for his portraits of the faceless poor. His sketches of street children, rural peasants and homeless and paintings of urban and rural landscapes bring to life the suffeirng of the poor and vividly illustrate China’s wealth gap. What is all the more remarkable about Zhang is that for a long a time he was one of the faceless poor himself. “At age 11 he was abandoned on the streets by a truck driver father from Shanxi Province with eight kids. With nowhere to sleep and nothing to eat, he he discovered that people would pay for his ink drawings sold on the sidewalk. Pen and ink literally saved him from starvation. Back then, the child artist sold his sketches for 8 jiao ($0.12) each. Thirty-five years and 20,000 sketches later, his black and white drawings of rural poverty sell for 8,000 yuan ($1,180.80) apiece.” [Source: Barry Cunningham, Global Times, August 4, 2010]

“In 1992, a patron paid 100,000 yuan to buy a Beijing hukou for Zhang. No longer did the artist need to scrounge for scrap lumber to create his woodblock prints, or forage in junkyards for metal to do his etchings. Today, Zhang's patrons are fiercely dedicated to his art, a fountain of creativity that spouts from his imagination 12 hours a day at his Beijing studio, with illustrations and artworks that now fill 164 books.”

“Today, I live a good life and often feel guilty that I cannot paint as I did over the past 20 years of perseverance, humility and poverty,: he told the Global Times. “But who else could understand what I encountered in my childhood?

“Zhang's landscapes were exhibited at the XYZ Gallery in Beijing's 798 Art District. Curator Cheng Guoqin says she is grateful that formal training didn't spoil Zhang's natural gift for art forged by a hard life. His buyers are touched by his experience. They can feel the shadow of their past.

Image Sources: Body Worlds, Lu Bolin, Tsang Tsou-choi

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021