SEMANG

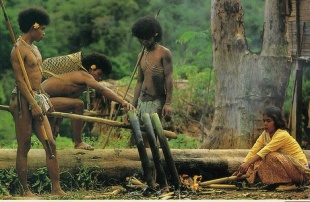

The Semang are a Negrito group of hunter-gatherers and shifting cultivators that live in the lowland rain forests in northern Malaysia and southern Thailand. Most Semang languages are in the Mon-Khmer group or the Aslian Branch of the Austroasiatic group of languages. Most also speak some Malay and there are many Malay loan words in Semang languages. [Source: Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

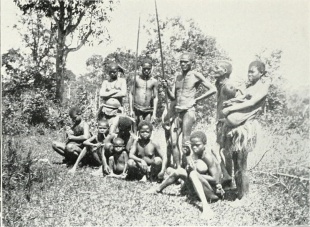

The term “Semang” was a nineteenth-century label for small, dark-skinned, curly-haired forest peoples of the Malay Peninsula, sometimes subdivided as “Pangan” in the east. Although the idea that they constitute a distinct race is now rejected, these groups share enough cultural traits to be treated as a single category. Outsiders have used names such as “Sakai,” “Orang Asli,” and the Thai “Ngò’ Pa,” while the peoples themselves use names like “Meni’” and “Batèk,” meaning “human beings (of our kind).” ~

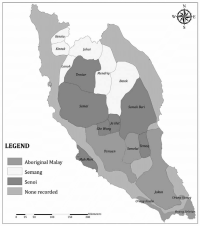

Semang generally live in the lowlands and foothills in primary and secondary tropical rain forest of Perak, Pahang, Kelantan and Kedah of peninsular Malaysia and southern Thailand between 3°55 and 7°30 N and between 99°50 and 102°45 E. Only the Jahai group inhabit higher elevations.In the past, the territory of the Semang settlements was larger, but neighboring ethnic groups pushed them into more remote areas. Today, the Semang, who are part of the Orang Asli group, live in urban areas of Malaysia alongside members of other ethnic groups. While a significant portion of these tribes live in permanent settlements, traditionally, groups from different time periods go into the jungle to harvest produce. Such cases most often take place at the end of fall, during the wild fruit season. Because of this tradition, they are often considered nomadic, though the Semang in Malaysia are no longer nomadic. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Semang have been recorded since before the A.D. 3rd century and have been described ethnologically as nomadic hunter-gatherers. In the early days the Semang may have interacted and traded with the Malay settlers after the first Malays arrived but relations soured when the Malays began taking Semang as slaves. After that many Semang retired into the forests. The Semang and other similar groups became known as the Orang Asli in peninsular Malaysia. Even though they were considered "isolated" they traded rattan, wild rubbers, camphor and oils for goods from China

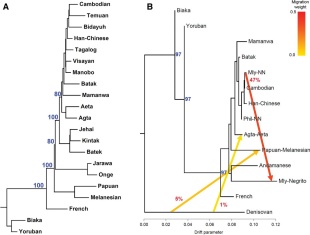

The Semang are grouped with other Orang Asli groups, which are diverse populations of distinct hunter-gatherers. Historically, they preferred to trade with the local population. For over a thousand years, some Semang remained isolated while others were subjected to slave raids or forced to pay tribute to Southeast Asian rulers. Other Negrito groups include the Andaman Islanders in India, the Veddoid Negritos of Sri Lanka and the Negritos of the Philippines and the Indian Ocean islands. The resemble other dark skinned, frizzy-haired people from Africa, Melanesia and Australia.

RELATED ARTICLES:

NEGRITOS (AETA) OF THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

See Sakai Under MINORITIES AND HILL TRIBES IN THAILAND factsanddetails.com

VEDDAS: THEIR HISTORY, LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

LIFE AND CULTURE OF THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND TRIBES factsanddetails.com

ORANG ASLI: GROUPS, HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHY LANGUAGES factsanddetails.com

SENOI: HISTORY, GROUPS, DREAM THEORY factsanddetails.com

TEMIAR: HISTORY, SOCIETY AND RICH RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MALAYSIA: HARMONY, DISHARMONY, GOVERNMENT POLICIES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA: DISCRIMINATION, SEPARATION, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

History of the Semang

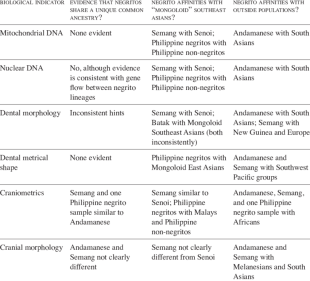

Negritos are of an unknown origin. Some anthropologists believe they are descendants of wandering people that "formed an ancient human bridge between Africa and Australia.” Genetic evidence indicates they much more similar to the people around them than had been previously thought. This suggests that Negritos and Asians had the same ancestors but that Negritos developed feature similar to Africans independently or that Asians were much darker and developed lighter skin and Asian features, or both. [Source: Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Semang are probably descendants of the pre-Neolithic Hoabinhian rain forest foragers who inhabited what is now the Malay Peninsula, arts of Sumatra, and Southeast Asia as far north as Vietnam, from 10,000 to 3,000 year ago. After the arrival of agriculture about 4,000 years, some became agriculturalists but enough remained hunter gatherers that they survived as such until recent times. At this time Austroasiatic-speaking migrants arrived and also brought to the Malaysan peninsula Aslian languages, which evolved into modern Senoic languages and Semang languages.

Beginning From about 500 B.C. there is evidence of forest people supplying India and China, with valuable forest product such as as aromatic woods, camphor, rubber, rattan, rhino horns, elephant tusks, gold and tin. The Srivijaya Empire (7th to 13th centuries) came into contact with Negrito peoples, who were sometimes presented as tribute. By the late 14th and early 15th centuries, Malay trading settlements emerged along the Strait of Malacca, centered on Malacca. They adopted Islam and their influence expanded inland, some indigenous groups were absorbed, while many Orang Asli, including the Semang, retreated further into the interior.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Semang and other indigenous groups were victims of the Batak and Rawa slave trade. In response to this, the Semang developed a tactic to avoid contact with outsiders. To preserve their autonomy, they would destroy their shelters immediately if an outsider intruded, and they would remain hidden in the jungle. As the Semang became increasingly isolated, surrounding societies came to view them as mysterious and even magical, often associating them with jungle spirits and folklore. Among Malay and southern Thai rulers, it was once considered prestigious to keep Negritos as exotic curiosities.

In the early twentieth century, Thailand’s King Chulalongkorn met the Semang and took an orphaned boy, Khanung, into the royal court, an event that led to royal patronage of the Semang. Under British rule, slavery was abolished and a protection policy for the Orang Asli was introduced, shaped by a romanticized view of indigenous peoples as “noble savages” needing protection from modern society. Many Orang Asli groups were moved onto “relocation settlements” in the 1970s in part so the government could carry out anti-insurgency operations against Communist insurgents.

Semang Groups

In Malaysia, at least ten tribes are commonly classified as Semang, though not all are officially recognized by the government.

1) Kensiu live in northern and eastern Kedah near the Thai border and Baling and southern Thailand (Yala Province), with most now settled in Kampung Lubuk-Legong in Baling District.

2) Kintak (Kintaq) occupy a single village near Gerik in Hulu Perak District, Perak, although they traditionally ranged around Klian Intan and parts of Kedah.

3) Lanoh reside in three villages in Hulu northwestern Perak near Gerik and include distinct subgroups such as the probably nomadic Lanoh Yir and the semi-settled Lanoh Jengjeng.

4) Semnam are closely associated with the Lanoh. They who live along the Ayer Bal River near Kampung Kuala Kenering but are not listed separately by JAKOA.

5) Sabub’n is a nearly extinct group whose remaining members live near Lenggong and Gerik.

6) Mendriq live in several villages along the middle reaches of the Kelantan River in the remote Gua Musang District of of central Kelantan. [Source: Wikipedia, Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

7) Jahai inhabit the mountainous region of northeastern Perak and northwestern Kelantan along the Perak–Kelantan border south of Thailand, the only highland area occupied by Semang groups. Their settlements are mainly along rivers and lakes, including Sungai Banun, Sungai Tiang, and Temenggor Lake in Perak, and Sungai Rual and Sungai Jeli in Kelantan.

Several groups are classified under the broader Batek category. 8) Bateg Deq (Batèk Dè') live in southeastern Kelantan and northern Pahang mainly along the Aring River in southern Kelantan, extending into Terengganu and Pahang. 9) Bateg Nong are found primarily in northern Pahang, with villages in Lipis and Jerantut districts, as well as small hamlets in Gua Musang, Kelantan. The 10) Mintil, also known as Mayah, live along Sungai Tanum in north-central Pahang near Chegar Perah in Lipis District and are officially recognized as part of the Batek.

Small Semang groups in Southern Thailand include the Tonga, Mos, Chong, and Ten'en call themselves Mani, though their linguistic affiliations remain unclear. The Mos and Chong live in southern peninsular Thailand in Trang Province and Phatthalung Province, several kilometers apart. Further south, there is another very small group of Semang near the Malaysian border in the southern part of Satun Province. The remaining Thai Semang groups live in Yala Province. In the upper part of the valley in the Than To district of this province, about two kilometers from the Thai-Malaysian border, there is a village that is home to the only settled Semang group in Thailand. There is another group of nomadic Semang living along the border with Malaysia in Yala province. Both nomadic and settled groups maintain close contact with Malaysia. The border here has only political significance and does not prevent the Semang from crossing it freely. [Source: Wikipedia[

Semang Population

There are only about 2,000 to 5,000 Semang depending on the source and they are divided into ten groups whose numbers range from about 100 to over 2,000. The population of Semang has remained at about 2,000 through the 20th century, but individual groups have increased or decreased as conditions changed. Because many of these groups are very small, several Semang communities are now at risk of disappearing. The 1986 Department of Aboriginal Affairs census reports:Kintak 107, Kensiu 135,Jahai 873, Mendriq 144, Batèk (including Batèk Dè', Batèk Tè', Batèk Nòng, and Mintil) 822, and Lanòh 229. [Source: Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Semang Population

Group — 1960 — 1965 — 1969 — 1974 — 1980 — 1996 — 2000 — 2003 — 2010

Kensiu — 126 — 76 — 98 — 101 — 130 — 224 — 254 — 232 — 280

Kintaq — 256 — 76 — 122 — 103 — 103 — 235 — 150 — 157 — 234

Lanoh — 142 — 142 — 264 — 302 — 224 — 359 — 173 — 350 — 390

Jahai — 621 — 546 — 702 — 769 — 740 — 1,049 — 1,244 — 1,843 — 2,326

Mendriq — 106 — 94 — 118 — 121 — 144 — 145 — 167 — 164 — 253

Batek — 530 — 339 — 501 — 585 — 720 — 960 — 1,519 — 1,255 — 1,359

Total — 1,781 — 1,273 — 1,805 — 1,981 — 2,061 — 2,972 — 3,507 — 4,001 — 4,842 [Source: Wikipedia]

Population of Semang by State (1996)

Kensiu: 180 in Kedah; 30 in Perak; 14 in Kelantan:Total: 224

Kintaq: 227in Perak and 8 in Kelantan: Total: 235

Lanoh: 359 in Perak: Total: 359

Jahai: 740 in Perak and 309 in Kelantan: Total: 1,049

Mendriq: 131 in Kelantan and 14 in Pahang: Total: 145

Batek: 247 in Kelantan; 55 in Terengganu and 658 in Pahang: Total: 960

Total — 180 — 1,356 — 709 — 55 — 672 — 2,972

The population of Semang in Thailand was estimated at 240 people (2010)

Semang Languages

All Semang languages—except that of the Lanòh, who speak a Central Aslian language—are in the Northern Aslian Family of the Aslian Stock of Mon-Khmer languages. These languages are also spoken by the neighbouring Senoi. Most Semang also speak Malay, and many Malay loanwords have been absorbed into all Semang languages. Not all Semang languages and dialects have survived, and some are already extinct. Others, such as Sabüm, Semnam, and Mintil, are currently endangered. Nevertheless, most Semang languages remain relatively stable despite their small number of speakers and are not immediately threatened with disappearance. [Source: Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

It is generally thought that the Aslian languages entered the Malay Peninsula from the north, originating in what is now Thailand. The ancestors of the Semang, however, were present on the peninsula long before the arrival of Austroasiatic speakers and must originally have spoken other, now unknown, languages. So far, no direct lexical evidence of these earlier languages has been identified.

Aslian is usually divided into four main branches: Northern Aslian, Central Aslian, Southern Aslian, and Jah Hut, the latter occupying a distinct position of its own. Among the Semang of Malaysia, a range of related languages and dialects are spoken, including Kensiu, Kentaq Bong, Kintaq Nakil, Jahai, Minriq, Bateg Deq, Mintil, Bateg Nong, Semnam, Sabüm, and the Lanoh Yir and Lanoh Jengjeng dialects. Most of these belong to the Northern Aslian branch, while the Lanoh language and its related dialects, together with the closely associated Semnam language, fall within Central Aslian. In Thailand, very few Semang languages have been studied in detail, most research focusing on Kensiu or Jahai.

A notable feature of Semang languages is the lack of sharp boundaries between them. This reflects the social organization of small, often nomadic groups, where people from different ethnic communities commonly share temporary camps. As a result, the Northern Aslian languages form a broad, interconnected linguistic continuum, while a similar but smaller network characterizes the Lanoh-related languages.

Semang Religion

The Semang have no religious authority or scripture and beliefs vary from group to group and even individual to individual. Even so there are similarities found among Semang and other Orang Asli. Most groups tend to see the world as a disk resting on the back of a snake or turtle. Above the earth is a paradise filled with flowers and trees. It is connected to the terrestrial world by stone pillars. [Source: Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Semang believe that a number of immortal superhuman beings live in the stone pillars and below the earth. Some were once humans and they occasionally return to earth and appear in people’s dreams. Many of these beings are grouped and linked with natural phenomena such as wind or fruiting trees. Important figures include the Thunder God (Karey; Batèk Dè'; Gobar) who has the power to topple trees on Semang who break taboos; the “Grandmother” of the underworld (Ya'),; and the snake that supports the earth, who can produce devastating floods. Most groups personify one or more other celestial beings (e.g., Kensiu, Tapn).

When punishing humans, the Thunder God may collaborate with the Grandmother, who produces a flood beneath the offender. The thunder god may also punish offenders with disease or a tiger attack. To avert his wrath, the offender makes a blood offering by scraping a small amount of blood from the shin with a knife. The blood is mixed with water and thrown to the thunder god and Grandmother.

Shaman are known as “hala”. They can be either male or female and often act as healers and receive some training through their dreams. These shaman use songs, massages, herbal medicines and spells to cure illnesses. Sometimes they go into trances in their healing ceremonies to cure diseases. The “big hala” is a supernatural being that can take the form of a tiger and scare off ordinary tigers.

Death and Afterlife: Upon death, most groups believe the shadow-soul goes to an island in the afterworld in the western horizon. After death, Semang become immortal superhumans who can visit Earth. Before the shadow-soul departs it sometimes lingers as a malevolent ghost. Most Semang groups bury their dead in shallow graves. Much of a traditional Semang funeral involves going through rituals and setting up protective measures to protect people from the malevolent spirits. Some groups practice tree burial, in which the dead are buried on a platform in a tree. Sometimes shaman are buried with their head above the ground.

Semang Society

The conjugal family is the most important social unit in Semang society. There are no descent groups and no bands that always camp together The camps are made of families that come together and break up as necessity and convenience apply. [Source: Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Semang are very egalitarian and place a strong emphasis on individual autonomy. . Camp groups traditionally have not had head men or leaders and the individual autonomy of families is respected. Social control is exerted through informal social pressure. Some taboos are enforced by the belief that if they are broken the offender will be punished by the thunder god. The Semang abhor violence. Disputes are generally settled through negotiations or public airing of a grievance and seeking a decision by the group. Individuals who are not on friendly terms join different camps.

Most activities and chores are done by both men and women and work is often done in mixed groups or husband and wife teams. Although both groups dig for tubers women spend more doing this than men. Men do most of the hunting and heavy chores such as felling large trees. Kinship is reckoned on both the paternal and maternal lines. For the Semang, there is no distinction between relatives, cousins, and siblings. However, they differentiate based on age, dividing their siblings into elder and younger groups. People are interconnected by ties of kinship and friendship. Social classes do not exist.

Leadership when it manifests itself is informal and based on personal charisma rather than authority, and such figures—men or women—may guide others without holding real power. The title penghulu, however, usually refers to a male leader appointed or recognized by the state, whose role is mainly to mediate between the group and outside authorities. These penghulu are salaried, formally elected under government supervision, often inherit the position, and hold little influence within everyday community life.

Semang Marriage and Family

Semang couples come together on their own accord; parents have little influence. There are some rules that discourage marriages of close relatives. A marriage is often defined when a couple starts living together. Sometimes there is a small feast and the groom gives some gifts to the bride’s family. Among more settled groups, the husband sometimes does a bride service for a year or two to the bride’s family. Couples may join the camp of the groom’s family or the bride’s family or alternate between both. [Source: Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Polygyny and polyandry are sometimes practiced but are rare. Divorce is acceptable in most cases, especially if the couple has no children. In most cases, the couple simply stop living together. For the most part the break ups are ultimately amicable and often divorced people remain in the same camps together.

In most cases parents and their preadolescent children share a lean-to. Adolescent girls stay in an adjacent lean-to. Adolescent boys from several families sleep together in their own lean to. Children are brought up by both parents although women usually devote more time to childrearing than men. Children tend to pick up skills through casual observation and participation rather than formal training.

Rules that prohibit physical contact with the opposite sex, supported by relevant taboos, make sexual relations outside of marriage difficult. Young children of divorced couples typically live with their mother, while older children often choose to live with one parent or the other. Stepparents usually refer to children from previous marriages as their own. ³ Just as in the case of divorce or the death of a wife, a Semang man may marry multiple times but remain monogamous. [Source: Wikipedia]

Semang Life

The Semang have traditionally lived in temporary camps lasting from one night to six week. The camps are comprised of a cluster of lean-tos with frames made from branches and covered in palm thatch. Each lean-to is home to a conjugal family, a widow and widower or a group of unmarried boys and/or girls. Each camp has two to 20 shelters with six to 60 people. [Source: Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The nomadic western Semang groups live in lean-to that are arranged in two rows, facing each other and forming a kind of tunnel. Semang who have settled, often have done so under pressure from the Malaysia government. They live in Malay-style bamboo and thatch houses, or cinder block houses built by the Department of Aboriginal Affairs. Many of the groups that live in government settlements use their houses as bases from which the groups go into the forest.

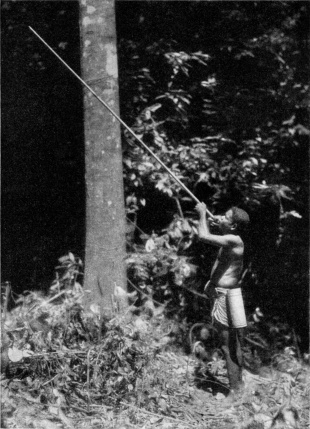

The Semang make extensive use of jungle plants in daily life. Bamboo is especially important, serving for house construction, blowguns and darts, fish traps, utensils, containers, mats, rafts, and ritual objects. Cooking vessels, water containers and sleeping platforms are made from bamboo. Mats, baskets and clothing are made from pandanus, Belts and ladders are made from rattan. Cloth used to made from bark. Wood is used for knife handles, sheaths, and cutting boards.

The Semang also rely on the forest for trade, collecting wild fruits and products such as rattan, rubber, beeswax, resinous woods, honey, and medicinal herbs to sell or exchange with nearby Malay villages or with Chinese and Malay traders for metal tools such as knives, spear points and digging blades and things like tobacco, flour and rice and cloth.

Many Semang have been displaced by dam projects, development and logging. The Department of Aboriginal Affairs has attempted to persuade the Semang to take up commercial crop production and has trained them do so. Many Semang have resisted this. ]

Semang Hunting and Gathering

Traditionally, the Semang hunted and gathered wild foods and traded forest products for cultivated food and manufactured goods. Even the onesconsidered nomadic plant a few crops from time to time and work for outsiders. Often they help Malays harvest their rice crop in return for a portion of the rice crop. Commonly harvested foods include petai, kerdas, keranji, jering, and durian, each gathered in specific seasons. All collected produce is shared within the camp, and income from sales is used to purchase essentials like rice, oil, salt, sugar, tobacco, clothing, and tools [Source: Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The staple of the nomadic Semang diet is wild yams, which come in 12 varieties and are valuable year round. Wild foods consumed include bamboo shoots, nuts, seasonal fruits. Hunters have traditionally used blowguns and poison darts to catch monkeys, gibbons and birds, their primary sources of wild meat. They also dig bamboo rats out of their burrows and fish with nets, poison, spears and hooks and lines. They used to hunt large game with bows and arrows but gave that up. The seldom used traps. Groups had loose claims to a particular area but these claims were not so strong and they were difficult to enforce.

When the Semang raised crops they practiced slash-and-burn agriculture and grew dry rice, cassava, maize, and sweet potatoes. Food is generally shared after the harvest. Sometimes dogs are kept as guard animals. They are relatively useless in hunting monkey and birds. Some settled Semang raise chickens for food and keep dogs and monkeys as pets.

Martin (1905) mentions that the southern groups of the Senoi and the Semang devour everything edible although vegetable food prevails. His statement that some insects are not eaten suggests that some insects are eaten. Bristowe (1932) was told by the Semang that they ate queen termites and the larvae of a greenish coconut beetle. [Source: “Human Use of Insects as a Food Resource”,Professor Gene R. De Foliart (1925-2013), Department of Entomology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002]

Semang Culture

The Semang enjoy singing. Both sexes sometimes put on flowers, leaves and pigments when the hold singing sessions. Blowpipes, quivers, and bamboo combs are sometimes decorated with geometric and floral patterns. Semang don't like to say thank you when receiving a portion of meat because it is considered rude to express surprise at a hunter's generosity or to size up the piece of meat received.

Scarification is practiced. Young boys and girls undergo a simple ritual to mark the end of their adolescence. A finely serrated sugarcane leaf is drawn across the skin and charcoal powder is rubbed into the cut. They have used divination by smoke (capnomancy) to determine whether a camp is safe for the night.

The Semang have bamboo musical instruments, including a jaw harp and a nose flute. Ingo Stoevesandt wrote in his website on Southeast Asia music: “Among the Orang Asli, the “Negrito” always built an instrument to use it once and then throw it away. Their nomadic life made it impossible to carry around heavy gongs or instruments which are complex in structure and easy to break. Today, the nomadic life is over and this also regards to the appearance of Negrito musical instruments today. Besides from all “jungle stories” the shamanistic rituals found among the Orang Asli are one of the latest chances to study shamanistic traditions and philosophies. Here we find music that works as a “bridge to heaven”, with drums beating players into trance.” [Source: Ingo Stoevesandt from his website on Southeast Asia music

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026