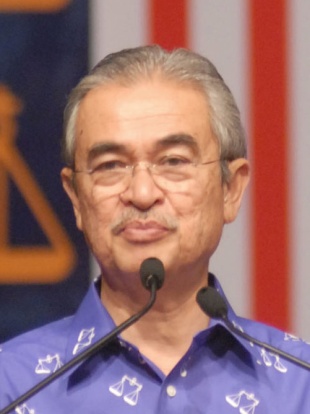

ABDULLAH AHMAD BADAWI

Tun Abdullah bin Haji Ahmad Badawi served as Prime Minister of Malaysia from 2003 to 2009. Malaysia’s 5th prime minister since it became independent in 1957, he was also the president of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), the largest political party in Malaysia, and led the governing Barisan Nasional parliamentary coalition. He is informally known as Pak Lah, 'Pak' meaning 'Uncle' while 'Lah' is taken from his name 'Abdullah'. He also called Father of Human Capital Development (Bapa Pembangunan Modal Insan).

In October 2003, after 22 tumultuous years in power, Dr Mahathir Mohamad retired and handed power to his anointed successor, Abdullah, who who was one of UMNO’s vice presidents and pledged to maintain Mahathir’s core policies but adopted a more restrained and conciliatory political style. After several months as an appointed prime minister, Abdullah sought a popular mandate and won a landslide victory in the March 2004 general election. His Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition expanded its already large majority, capturing more than 90 percent of parliamentary seats and about 64 percent of the vote, while the opposition Parti Islam se-Malaysia (PAS) suffered heavy losses at both the national and state levels. During the campaign, Badawi stressed greater transparency in government and promoted Islam Hadhari (“Civilizational Islam”), portraying it as a moderate, open, and tolerant alternative to more fundamentalist interpretations of Islam. After the 2004 win, Abdullah was criticised by Mahathir for degrading the freedom of the press and for scrapping projects such as a new bridge between Malaysia and Singapore that would have replaced the existing causeway. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Abdullah has been a politician most of his life, Known as “Mr. Clean” and “Mr. Nice-guy,” he served as foreign minister and education minister before being named as deputy prime minister in 1998 when Anwar Ibraham was sacked. He was widely respected among the middle class and regarded as consensus builder. He is calm and affable where Mahathir was brash and abrasive. Sean Yoong of Associated Press wrote: “Abdullah is considered milder than the blunt-spoken Mahathir, an advocate of the developing and Islamic worlds and known for his fiery criticism of globalization and U.S. policy in the Middle East. Dubbed the "Mr. Nice Guy" of Malaysian politics, Abdullah, who has a degree in Islamic studies and once worked in the civil service, waded into politics after the death of his father, a pioneer member of the ruling party. He entered Parliament in 1978, holding the education, defense and foreign affairs portfolios before becoming Mahathir's deputy. [Source: Sean Yoong, Associated Press, November 2, 2003]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MAHATHIR MOHAMAD: HIS LIFE, VIEWS, CHARACTERS, OUTRAGEOUS STATEMENTS factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA UNDER MAHATHIR MOHAMAD factsanddetails.com

ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS OF 1997-98 IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

NAJIB RAZAK: LIFE, POLITICAL CAREER, SCANDALS factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA UNDER PRIME MINISTER NAJIB RAZAK 2009-2018 factsanddetails.com

1MDB SCANDAL: BILLIONS, BIRKIN BAGS, CELEBRITIES, JHO LOW, JAILTIME FOR NAJIB factsanddetails.com

ANWAR IBRAHIM'S LIFE AND POLITICAL CAREER factsanddetails.com

ANWAR IBRAHIM'S TRIALS, LEGAL PROBLEMS AND TIME IN JAIL factsanddetails.com

ANWAR IBRAHIM FINALLY BECOMES PRIME MINISTER factsanddetails.com

RISE OF MODERN MALAYSIA 1963-1990: DEVELOPMENT, ECONOMICS, POLITICS factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIAN INDEPENDENCE AND THE CREATION OF MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA AFTER WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

RACIAL DISCORD IN MALAYSIA: RIOTS ON MAY 13, 1969, AFFIRMITIVE ACTION, BOAT PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

ELECTIONS IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

POLITICS IN MALAYSIA: LEADERS, ETHNICITY, RELIGION, SYMBOLS, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

POLITICAL PARTIES IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

Life and Family of Abdullah Ahmad Badawi

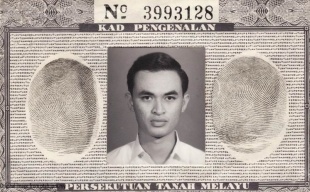

Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, born in November 1939 in Bayan Lepas, Penang, came from a family with deep religious roots. Both his father and grandfather were respected religious teachers. He received his early education at Bukit Mertajam High School and later completed his Sixth Form at Methodist Boys’ School, Penang. In 1964, he graduated from the University of Malaya with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Islamic Studies. After university, he joined the Malaysian Administrative and Diplomatic Corps, beginning a long civil service career that included serving as Director of Youth at the Ministry of Youth and Sports and as secretary of the National Operations Council (MAGERAN).

Badawi’s paternal grandfather, Syeikh Abdullah Badawi Fahim, was of Arab descent and was a highly regarded religious leader and nationalist. He was a founding member of Hizbul Muslimin, which later evolved into the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS), and after independence became the first Mufti of Penang. Abdullah’s father, Ahmad Badawi, was also a prominent religious figure and a member of UMNO. On his mother’s side, his grandfather, Ha Su-chiang, was a Utsul Muslim who migrated from Sanya in Hainan. [Source: Wikipedia]

Abdullah became prime minister in 2003 at the age of 63. His first wife, Endon Mahmood, a former colleague from the civil service, was known for not wearing a headscarf and for leading the group Sisters in Islam, which promotes monogamy as a Muslim ideal. The couple had been married for 40 years when Endon died of breast cancer on 20 October 2005. While still serving as prime minister, Abdullah remarried. In 2007, he married Jeanne Abdullah, the manager of his official residence, in a private ceremony held at his official home in Putrajaya and attended only by close family members. After the wedding, the couple visited Endon Mahmood’s grave, and their first overseas trip together was to Brunei for the wedding of the Sultan of Brunei’s daughter. [Source: Reuters, June 10, 2007]

Political Career of Abdullah Ahmad Badawi

Abdullah Ahmad Badawi entered electoral politics in 1978 when he won a parliamentary seat for UMNO in the constituency of Kepala Batas in northern Seberang Perai, an area previously represented by his late father. His strong religious background made it difficult for Islamic fundamentalists to portray him as insufficiently committed to Islam, helping to bolster his political credibility among Malay voters.

Early in Mahathir Mohamad’s tenure as prime minister, UMNO was torn by an intense internal struggle that split the party into two factions: “Team A,” led by Mahathir and his loyalists, and “Team B,” which supported former Finance Minister Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah and former Deputy Prime Minister Musa Hitam. Mahathir ultimately emerged victorious, and Tengku Razaleigh was excluded from the newly formed UMNO (Baru). Abdullah, who was closely aligned with his mentor Musa Hitam in Team B, suffered politically as a result and was dismissed from his post as Minister of Defence. However, he did not join Tengku Razaleigh’s breakaway party, Semangat 46, which later became defunct. [Source: Wikipedia]

When UMNO (Baru) was established in February 1988, Mahathir brought Abdullah back into the party leadership by appointing him to the pro tem committee as a vice president, a position he retained following the 1990 party elections. In a cabinet reshuffle in 1991, Mahathir returned Abdullah to the Cabinet as Minister of Foreign Affairs, a post he held until November 1999, when he was succeeded by Syed Hamid Albar. Although Abdullah lost his UMNO vice-presidency in the 1993 party elections, he remained in the Cabinet and continued to serve in senior ministerial roles. Over the years, he held several key portfolios, including Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department, Minister of Education, Minister of Defence, and Minister of Foreign Affairs. His long period of political rehabilitation culminated in his appointment as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Home Affairs following the dismissal of Anwar Ibrahim.

Abdullah Steps Out Mahathir Shadow

It was thought Abdullah would pretty much follow in Mahathir’s footsteps but that was not the case. A few months after taking office he embarked on a high profile anti-corruption campaign and canceled one Mahathir‘s most cherished pet projects: the $3.7 billion cross-Malaysia railroad project, Malaysia’s largest infrastructure program, whose contact had been awarded to a Mahathir crony. Abdullah has promoted rural development and a moderate form of Islam and freed Anwar, which was seen as a portent of a mild liberalisation.. And he did all this while continuing Malaysia’s impressive emergence from the 1997 economic crisis and maintaining robust economic growth.

A year after taking office as prime minister, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi had established himself as a leader distinct from his predecessor, Mahathir Mohamad, projecting quiet confidence and independence rather than trying to emulate Mahathir’s dominant style. He presided over one of Malaysia’s most significant political shifts in years, reversing or shelving several of Mahathir’s policies and placing greater emphasis on public welfare, consensus-building, and a more democratic approach to governance. Source: Sean Yoong, Associated Press, October 25, 2004]

Abdullah moved away from costly mega-infrastructure projects, improved relations with countries such as the United States, Australia, and Singapore, and launched an anti-corruption drive that included action against figures linked to Mahathir. He also tacitly supported the release of Anwar Ibrahim, Mahathir’s former deputy and political rival, a move widely seen as a major political turnaround. Although Abdullah lacked Mahathir’s charisma, he quickly asserted authority within the ruling coalition, won strong support from the business community, and boosted his popularity by adopting a less confrontational political style. His leadership was consolidated in March, when the National Front secured an overwhelming parliamentary victory, giving him a strong five-year mandate.

Malaysia General Election in 2004

In the March 2004 general election, the United Malays National Organization (UMNO)-dominated Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition won 198 of the 219 seats in the lower house of Parliament and 11 of the 12 contested state governments. The opposition Parti Islam se Malaysia (PAS) won only six seats and lost even in conservative Muslim states, while the Democratic Action Party (DAP) won 12 seats, making Lim Kit Siang of the DAP the opposition leader in the Malaysian parliament. The PAS and the DAP were at odds over religious policy issues, leaving the opposition in a weakened position. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

In the March 2004 general election, the Barisan Nasional (National Front) led by Abdullah had a massive victory, virtually wiping out the PAS and Keadilan, although the DAP recovered the seats it had lost in 1999. This victory was seen as the result mainly of Abdullah's personal popularity and the strong recovery of Malaysia’s economy, which has lifted the living standards of most Malaysians to almost first world standards, coupled with an ineffective opposition.

Abdullah’s and Mahathir’s National Front coalition took 198 (90 percent) of the 219 seats. It was the biggest parliamentary majority ever. The Islamic Party PAS, collapsed from 27 to 7 seats. The Democratic Action Party became the major opposition party by increasing the number of seats from 10 to12. Keadilan (National Justice Party) held on to only one of its previous five seats, the seat held by Anwar’s wife Azizah Ismail.

Abdullah seemed to have the right mix of continuing some Mahathir policies and establishing new ones. His anti-corruption campaign and his religious background gave him the moral high ground and deprived the opposition of their complaints and issues with the ruling party. The opposition alleged fraud and demanded new elections. Not much came of the allegations or demands. In July 2004, Abdullah secured the top position in the ruling party after his top opponent couldn’t even secure enough nominations to oppose him.

Abdullah Ahmad Badawi as Prime Minister

As Abdullah Ahmad Badawi settled into office, he sought to consolidate support within UMNO by easing earlier austerity measures that had angered party members dependent on government contracts. To placate these concerns, his government launched a US$15 billion infrastructure development project in Johor, a key UMNO stronghold. Internationally, Abdullah criticised Western countries for focusing too heavily on terrorism while neglecting global poverty, and domestically he urged Malaysians to move beyond an excessive preoccupation with race and religion. Human rights issues drew limited public attention, reflecting political fatigue after Mahathir’s long rule.

Although Abdullah initially faced criticism for lacking decisiveness and being reluctant to confront entrenched interests in UMNO, gradual but meaningful changes became evident. Courts were allowed to act independently, leading to Anwar Ibrahim’s release; official reports exposed corruption and abuses within the police; a senior UMNO minister was suspended for corruption; and the media and Parliament gained slightly more space for dissent and scrutiny. Senior appointments increasingly favoured professional credibility, and relations with key partners such as the United States, Australia, and Singapore improved. [Source: Philip Bowring, New York Times, August 5, 2005]

Despite these reforms, Abdullah was still seen as constrained by party pressures, with an unchanged cabinet and lingering Mahathir-era influence. His consensual, delegated leadership style slowed decision-making and frustrated some in the business community. While he remained more popular with the public than within UMNO, Abdullah emerged strongly from the party’s annual assembly, reaffirming his commitment to clean government and continuing to challenge Malays to reduce dependence on preferential policies and better seize opportunities for economic and educational advancement.

The Badawi government’s approach to illegal immigrants—most of them from conflict-prone areas of Indonesia and Myanmar—was widely seen as inconsistent. A tough law introduced in 2002 forced large numbers of Indonesians and Filipinos to leave Malaysia, straining relations with Indonesia as an estimated 400,000 workers returned home. This was followed by a second wave in late 2004 and early 2005, when about half a million undocumented immigrants departed under a government amnesty. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007; Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

In March 2005, the amnesty gave way to a crackdown, with immigrant workers detained, imprisoned, and deported. However, the policy soon ran up against economic realities. Labour shortages, especially in the construction sector, emerged as the slow inflow of legally permitted workers failed to meet demand. By May 2005, the government reversed course and allowed Indonesians seeking work to enter on tourist visas. Throughout this period, Malaysia continued to attract foreign labour, but official policy toward undocumented workers, political refugees, and asylum seekers remained unclear and uneven.

Economic Policy Under Abdullah Ahmad Badawi

After Mahathir stepped down in 2003, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi became prime minister, softened earlier economic controls under business pressure, projected a more moderate image, and moved against several figures associated with corruption. These measures helped him secure a landslide election victory in 2004. He promoted foreign investment, privatisation, and free trade, including a major agreement with Japan. [Source: Dante Pastrana, World Socialist Web Site, April 2, 2009; Thomas Fuller, New York Times, March 7, 2008, AP, March 7, 2008; Philip Bowring, New York Times, August 5, 2005]

Malaysia experienced strong economic growth between 2004 and 2007, driven largely by exports of electronics, though growth slowed at times and inflation and unemployment remained moderate. Key policy shifts included ending the ringgit’s peg to the US dollar in 2005 and raising interest rates to curb inflation. Analysts argued that currency reform reduced protection for inefficient industries and created opportunities for broader economic restructuring.

Despite these gains, public concern grew over rising prices, inequality, crime, and ethnic relations. Income distribution remained highly unequal, and many in the business community—especially ethnic Chinese—were pessimistic about future prospects. By 2006, Abdullah’s popularity declined as he was blamed for inflation, corruption, crime, and worsening ethnic tensions linked to long-standing affirmative action policies favouring Malays. By early 2008, shortages and rationing of subsidised goods such as cooking oil further highlighted economic and political strains.

Malaysia and the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-2009

During the 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis, Malaysia’s economy slowed sharply as falling commodity prices hurt palm oil, rubber, oil, and gas, while weak global demand damaged the electronics sector and exports. The country entered its first recession in a decade, with growth plunging to –6.2 percent in the first quarter of 2009 before rebounding later in the year; overall, the economy contracted by 1.7 percent in 2009. [Source: Liz Gooch, New York Times, August 31, 2009; Elffie Chew, Wall Street Journal, March 11, 2008]

Unemployment rose and layoffs increased, with more than 31,000 job losses recorded in the first seven months of 2009 and unemployment reaching 4 percent. Although conditions improved by mid-2009 and the economy emerged from recession, labor unions urged restrictions on foreign workers to protect local jobs.

To counter the downturn, the government launched its largest-ever stimulus program, a 60-billion-ringgit ($16 billion) package equal to about 9 percent of GDP, alongside earlier measures and significant interest-rate cuts by the central bank. The stimulus aimed to boost confidence, curb unemployment, and support struggling companies, helping stabilize the economy and prevent a deeper collapse.

Criticism of Badawi and Clash with Mahathir

By 2006, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi had lost much of the goodwill he enjoyed when he took office in 2003 and was increasingly blamed for failing to manage inflation, crime, corruption, and rising ethnic tensions. Minority communities complained of persistent discrimination under long-standing pro-Malay affirmative action policies, court rulings favoring Malays in religious disputes, and incidents such as the demolition of Hindu temples, which angered many Indians. At the same time, Abdullah was criticized as weak and out of touch by both the opposition and figures within his own party, including Mahathir. He was portrayed as indecisive and complacent amid worsening social and economic problems, with critics even mocking him as inattentive and lethargic. Although opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim called for an end to racial discrimination, Abdullah’s leadership increasingly appeared adrift, and perceptions grew that corruption was continuing or even worsening under his administration. [Source: AP, March 7, 2008; Thomas Fuller, New York Times, March 7, 2008; Richard Lloyd Parry, The Times, October 30, 2006]

After Abdullah cancelled several major projects, including a proposed bridge to Singapore, sharp tensions emerged with his predecessor Mahathir Mohamad. In 2007 Mahathir publicly denounced Abdullah, accusing him of corruption, authoritarianism and running a “police state,” claims Abdullah denied.

The clash was striking given Mahathir’s own long record of repression while in office, making his criticisms appear deeply ironic to many Malaysians. Under Abdullah, the press had become somewhat freer and some detainees were released without trial. Despite the public attacks, Abdullah managed to fend off an internal party challenge by using strong, centralized control similar to Mahathir’s own methods, as their rivalry became one of the defining political dramas of the period.

Scandals, Corruption and Protests Under Abdullah

Abdullah’s administration was increasingly undermined by scandals and controversies that tarnished his reformist image as “Mr. Clean.” High-profile cases, including the murder trial involving a senior aide and police commandos linked to his security detail, and the release of a video allegedly showing judicial appointment brokering, intensified public concern over corruption and judicial independence. [Source: Thomas Fuller, New York Times, March 7, 2008; Al-Jazeera, July 6, 2008; David Chance, Reuters, October 9, 2008; Wikipedia]

Despite winning a landslide victory in 2004 on an anticorruption platform, Abdullah failed to curb entrenched corruption and nepotism within UMNO and the ruling Barisan Nasional coalition. Malaysia’s standing on Transparency International’s corruption index slipped, and public disillusionment contributed to the government’s worst electoral showing in 2008, ultimately forcing Abdullah from office.

Mounting unrest was reflected in large street protests in 2007 and 2008, including mass rallies demanding electoral reform, an end to ethnic discrimination, and opposition to sharp fuel price hikes. Government attempts to suppress these demonstrations further fueled public anger and highlighted the growing crisis of confidence in Abdullah’s leadership.

2008 Elections in Malaysia

In late 2007 and early 2008, there was an increase in public unhappiness among Malaysians of South Asian descent regarding their lagging standard of living relative to Malays and Chinese. These concerns carried over into the March 2008 parliamentary elections. Though the National Front retained a majority, it failed to win two-thirds of the seats for the first time since 1969 and lost control of five states (one of which returned to National Front control in 2009). The Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS), Anwar Ibrahim's Justice Party, and the largely Chinese Democratic Action Party all gained seats. The election results led to calls for Abdullah to resign, and he eventually announced that he would step down in March 2009. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

In the 2008 elections, Abdullah’s National Front coalition retained power but lost its two-thirds parliamentary majority, control of five states, and most urban areas. The opposition surged to 82 of 222 parliamentary seats, up from 19, depriving the government of its long-held ability to amend the constitution at will. UMNO and its allies lost key states such as Penang, Selangor, Kedah, and Perak, while failing to regain Kelantan. The results signaled the emergence of a viable two-party system and a major shift in Malaysia’s political landscape. The opposition’s gains were driven by widespread dissatisfaction over corruption, inequality, rising prices, crime, and ethnic discrimination. Led largely by Anwar Ibrahim’s People’s Justice Party and supported by PAS, the opposition capitalized on public anger toward the ruling elite, marking a turning point in Malaysian politics. [Source: Vijay Joshi, Associated Press, March 8, 2008; Associated Press, March 10, 2008; Niluksi Koswanage, Reuters, March 11, 2008; Dante Pastrana, World Socialist Web Site, April 2, 2009]

See Separate Article ELECTIONS IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

Abdullah Ahmad Badawi’s Downfall and Retirement

UMNO’s poor performance in the 2008 elections plunged the party into crisis, with many leaders blaming Abdullah Ahmad Badawi’s moderate policies for the defeat. The opposition gained further momentum when Anwar Ibrahim won a by-election in August 2008 and entered parliament, heightening pressure on Abdullah amid renewed sodomy charges against Anwar. Although Abdullah initially rejected calls to resign, insisting he still had a mandate despite heavy losses, dissent within UMNO intensified. [Source: Sean Yoong, Associated Press, October 20, 2008; Al-Jazeera, April 2, 2009; Dante Pastrana, World Socialist Web Site, April 2, 2009; Associated Press, March 14 2008]

Mahathir quit UMNO in protest and urged others to follow, deepening instability within the ruling coalition. Smaller coalition partners began to defect, raising fears that the government could collapse through parliamentary defections. Under mounting internal and external pressure, Abdullah announced in October 2008 that he would step down as UMNO president and prime minister.

Abdullah formally relinquished office in April 2009, handing power to his deputy, Najib Razak. He left office remembered for allowing greater political openness than his predecessor, but also for unfulfilled promises on corruption, institutional reform, and governance—failures that contributed to his downfall and to what he later described as “missed opportunities.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026