LIFE IN JAPAN IN THE EDO PERIOD

Edo (Tokyo) was made the capital of Japan by the Tokugawa shogunate. When the shogunate set up a fortress city there around 1600 it was a small village. By 1700, it was the largest city on the world, with a population of 1,200,000, compared to 800,000 in London and 500,000 in Paris at that time. Edo society was very urbanized. Urban fashion spread outwards from Edo and people came from the country to seek employment during the slack agricultural season or in difficult times.

Japan became affluent enough in the Edo Period that many Japanese were able to switch from eating two meals to three meals a day. Typical dishes included rice, fish and tofu. People began seasoning their food with sweet sake and soy sauce. Sweet potatoes and pumpkins were introduced from overseas. One cookbook contained more than 100 recipes for tofu that were graded into six levels: mediocre, standard, fine, novel, delicious and supreme. A recipe for boiled tofu went: “Put tofu into an open pot of boiling kudzu starch gruel. Wait until the tofu starts to move slightly and scoop it up just as it is about to float."

Life was difficult for the rural populations but not so difficult that they rose up in revolt. The worst hardships were disease, famine and earthquakes. The Great Meireki Fire in January 1657 destroyed Edo Castle. In 1732, nearly 1 million people starved to death in a famine caused by poor harvests. Hundreds of thousands more died of cholera.

Many people sushi think must have been since time immortal in Japan---according to some sources sushi originated in China and came to Japan in the 8th century---but it was in fact was invented around 1850 by Tokyo street vendors as a snack. The nigiri-zushi (modern sushi) was tasty, nutritious and cheap and became a staple of Tokyo’s poor. Sushi didn't really catch on nationwide until the 1950s when modern transportation and refrigeration made it easier to keep it fresh.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS SAMURAI AND THE TALE OF 47 RONIN factsanddetails.com; NINJAS IN JAPAN AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com; NINJA STEALTH, LIFESTYLE, WEAPONS AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; WOKOU: JAPANESE PIRATES factsanddetails.com; MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN: KUBLAI KHAN AND KAMIKAZEE WINDS factsanddetails.com; MUROMACHI PERIOD (1338-1573): CULTURE AND CIVIL WARS factsanddetails.com; MOMOYAMA PERIOD (1573-1603) factsanddetails.com; ODA NOBUNAGA factsanddetails.com; HIDEYOSHI TOYOTOMI factsanddetails.com; TOKUGAWA IEYASU AND THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com; EDO (TOKUGAWA) PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; CULTURE IN JAPAN IN THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; MARCO POLO, COLUMBUS AND THE FIRST EUROPEANS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND THE WEST DURING THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DECLINE OF THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com; EDO PERIOD ART: SAMURAI ART, URBAN ART, DECORATIVE AND GENRE PAINTING factsanddetails.com; UKIYO-E (JAPANESE WOODBLOCK PRINTS): MAKING AND COLLECTING IT, SEX AND VAN GOGH factsanddetails.com; UKIYO-E ARTISTS: SHARAKU, HOKUSAI, HIROSHIGE AND UTAGAWA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on the Edo Period: Essay on the Polity opf the Tokugawa Era aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on the Edo Period Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the History of Tokyo Wikipedia; Making of Modern Japan, Google e-book books.google.com/books ; Wikipedia article on the Momoyama Period Wikipedia ; Culture in the Edo Period Edo-Tokyo Museum edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp ;Edo Virtual Tour us-japan.org/edomatsu ; Tokugawa Art Museum tokugawa-art-museum. ; Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de Ukiyo-e Viewing Japanese Prints viewingjapaneseprints ; Ukiyo-e Pictures of te Floating World ukiyo-e.se ; Christianity in Japan: Japan-Photo Archive of Christianity japan-photo.de ; Wikipedia article on Christianity in Japan Wikipedia ; Catholic Encyclopedia Article on Japan (scroll down for info on Christianity in Japan) newadvent.org ; History of Japanese Catholic Church english.pauline.or.jp ; Artelino Article on the Dutch in Nagasaki artelino.com ; Samurai Era in Japan: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Artelino Article on Samurai artelino.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Musui's Story: The Autobiography of a Tokugawa Samurai” by Katsu Kokichi and Teruko Craig Amazon.com“The Shogun's Soldiers: Volume 2 - The Daily Life of Samurai and Soldiers in Edo Period Japan, 1603–1721' by Michael Fredholm von Essen Amazon.com; “Japanese Art of Edo Period (1999) By Guth Christine Amazon.com; “Edo, The City That Became Tokyo: An Illustrated History” by Akira Naito (Kodansha Press, 2003) Amazon.com; “Tokugawa Shogunate: Final Feudal Era of Japan” by in60Learning Amazon.com; "The Dog Shogun: The Personality and Policies of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi” by Beatrice M. Bodart-Bailey Amazon.com; “Giving Up the Gun” by Noel Perrin Amazon.com; “Shogun: The Life and Times of Tokugawa Ieyasu: Japan's Greatest Ruler” (Tuttle Classics) by A. L. Sadler, Stephen Turnbull, Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “Shogun” by James Clavell Amazon.com; “Shogun & Daimyo: Military Dictators of Samurai Japan” by Tadashi Ehara Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan” by John Whitney Hall (Editor), James L. McClain Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 3: Medieval Japan” by Kozo Yamamura Amazon.com; “A History of the Samurai: Legendary Warriors of Japan” by Jonathan Lopez-Vera and Russell Calvert Amazon.com; “Bushido: The Samurai Code of Japan” (1899) by Inazo Nitobe Amazon.com; “The Samurai Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive Guide to Japan's Elite Warrior Class” by Constantine Nomikos Vaporis and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com

Bakufu Bureaucracy

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Bakufu was a large bureaucracy. In theory, and sometimes in practice, the shogun ruled as absolute dictator. In fact, some shoguns were weak-willed, incompetent, or simply lazy. The bakufu machinery functioned reasonably well with or without strong shogunal leadership.The two most important agencies within the bakufu were the Senior Councilors (roju, literally "elders within") and the Junior Councilors (wakadoshiyori, literally, "younger elders"). The Senior Councilors usually consisted of four or five daimyo of a certain type. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“Each individual councilor served as overall bakufu administrator on a monthly rotational basis. The whole group met in council to decide important matters of state, such as the selection of a new shogun should the previous one die without naming a successor. The Senior Councilors also supervised several high-ranking officials such as the commissioners that administered the major cities (e.g., Osaka and Nagasaki, both bakufu-administered), those that oversaw shrines and temples, those in charge of revenue and finance, and others. The Senior Councilors were a powerful group. Some shoguns gave them wide latitude; others tried to rein them in.~

“The Junior Councilors, all of whom were daimyo, were like the Senior Councilors but with slightly lower status. They supervised inspectors, who kept watch over bakufu retainers of sub-daimyo rank. The Junior Councilors also supervised the bakufu’s corps of intendants. These intendants administered parcels of the bakufu’s extensive land holdings throughout Japan. Another important task of the Junior Councilors was supervision of the day-to-day operation of the shogun’s castle in Edo.” ~

Daimyo procession

Types of Daimyo

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: In the Tokugawa period, there were over two hundred daimyo throughout Japan, whose domains varied in size from tiny (10,000 units of rice productivity) to vast (over half a million units of rice productivity). There were three categories of daimyo. Fudai were those daimyo personally allied with Tokugawa Ieyasu at the time of the Battle of Sekigarhara in 1600. Tozama were those daimyo not allied with Tokugawa Ieyasu at the time of the battle, including those who fought against him and those who did not. Shinpan daimyo were Tokugawa family relatives. In its early period, the bakufu designated three branches of the Tokugawa family (descending from Ieyasu) as daimyo lineages and potential heirs to the office of shogun should the main line fail to produce a suitable male heir. Later, three more branches assumed shinpan status, making a total of six. Some but not all of these branches had the Tokugawa surname. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“As we have seen, some daimyo not only administered their own domains but also worked as high-ranking bakufu officials. For bakufu offices requiring daimyo status, normally, only fudai were eligible to for appointment. Shinpan daimyo occasionally served as bakufu officials, typically as regents for a boy shogun. Tozama were ineligible to become bakufu officials. The fudai domains were small and often clustered around the larger tozama domains. The first three shoguns worked to create a geographic balance by surrounding tozama domains with the presumably more trustworthy fudai, with the fudai located in positions of strategic importance. Maintaining a balance of power, geographically and otherwise, between all potentially conflicting interests and groups was a conscious policy of the early shoguns. ~

“After Ieyasu’s victory, all the daimyo throughout Japan swore allegiance to the Tokugawa house. Such oaths would hardly have been worth the paper on which they were written had not the shogun and his government (which, of course, included some daimyo--an incentive for these daimyo to preserve the bakufu) held the preponderance of military and economic power. The bakufu directly controlled one-fifth of Japan’s agricultural land, making it the largest single land holder by far. It was taxes from this land that provided most of the bakufu’s income. The bakufu also controlled all major cities and ports, even if they would otherwise be part of another daimyo’s domain. It owned all the gold and silver mines throughout Japan. In theory at least, the daimyo ruled at the pleasure of the shogun, who formally reappointed the daimyo from time to time and had the authority to confiscate or reduce any domain. The first three shoguns often did confiscate domains of daimyo they suspected of disloyalty or other problems. As time when on and the domains became well established, confiscations by the bakufu took place only under highly unusual circumstances.” ~

Relations Between Daimyo and the Bakufu

Daimyo Naito Ienaga and his wife

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Bakufu relations with the daimyo were complex. In some respects, the shogun was simply a very large and powerful daimyo. In other respects, such as when dealing with foreign countries, the shogun was the singular leader of all of Japan. The bakufu imposed numerous restrictions on daimyo, the most important of which are included in the excerpts from Laws for Warrior Households above. Daimyo were limited to a single castle and had to obtain bakufu permission to make any repairs on it. Daimyo were forbidden to act in concert with each other on any matters of policy. Their relationships, in other words, were to be with the shogun and the people of their domains, not each other. Even marriages were subject to shogunal approval. Should a daimyo appear to have accumulated a major surplus of wealth, the shogun might require him to build a bridge or do some other sort of work for the public good outside his own domain--in part as a way of draining off some of that wealth. Alternate attendance also kept daimyo expenses up. Bakufu inspectors visited each domain from time to time. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“The bakufu clearly held more power than any daimyo. The daimyo nevertheless governed with a high degree of autonomy within their domains. Daimyo, for example, paid no regular taxes to the bakufu. As long as they fulfilled their duties to the shogun, abided by the restrictions mentioned above, and caused no major problems, daimyo were free to govern as they saw fit. Some domains issued their own currency, good only within its borders, and laws sometimes varied from one domain to the next. In the early decades of the Tokugawa period, the daimyo were a culturally diverse group. By the second and third generations, however, all daimyo spent their formative years in Edo, which resulted in a high degree of cultural homogeneity among them. ~

“As the years went by, both the bakufu and the various daimyo domains encountered fiscal problems and accumulated ever larger debts to the leading business establishments in Osaka and Edo. Indeed, the samurai class as a whole--which depended on fixed incomes, the value of which steadily shrank owing to inflation--tended to sink into poverty throughout the eighteenth century. In the long run, it was the merchants who prospered during the Tokugawa period. Mainly for this reason, Tokugawa-era culture tended to celebrate merchant values and material wealth. We examine certain aspects of Tokugawa-period culture in the next two chapters. Here, we jump to the end of the Tokugawa period to see how it fell and to sketch the outlines of the modern state that replaced it.” ~

Rules in the Edo Period

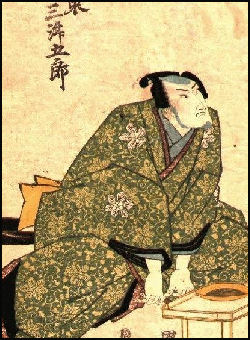

Edo-period samurai Edo-period samurai During the Edo period only samurai were allowed to carry weapons, life was ordered according to strict Confucian principals of duty and family loyalty, and people were restricted to their villages and only allowed to leave on special holidays or to visit special shrines.

There were also rigid caste-like rules that defined what people could wear eat and eat. Social status was defined by birth and social mobility was prohibited. The result of all this was peace, stability and flourishing of sanctioned arts such as kabuki, haiku poetry, ceramics, lacquerware, painting and weaving but little freedom.

People were told the size and kind of house they could live in, based on class and rank more than wealth. Farmers, no matter how rich, could not have grander homes than low-ranking samurai who often owed money to the farmers.

The Tokugawa passed a strict dress code, forbidding merchants from wearing embroidered silk, to cub inflationary spending and keep a lid on social pretension. People were told the designs and materials to use for their the clothes they wore and objects the used. There were even rules that designated the food people ate and the dates when people were supposed to change from their winter clothes to their summer clothes. Even horses needed identity cards to move around.

Excerpts from Laws for Warrior Households: 1) The arts of peace and war, including archery and horsemanship, shall be pursued single-mindedly. 2) Drinking parties and wanton revelry are to be avoided. 3) Offenders against the law shall not be harbored or hidden in any domain. 4) Whenever one intends to make repairs on a castle of one of the domains, bakufu authorities should be notified. All construction of new castles is to be stopped and never resumed. 5) Immediate report should be made of innovations which are being planned or factional conspiracies being formed in neighboring domains. 6) Do not enter into marriage privately [i.e., without notifying bakufu authorities]. 7) Visits of the daimyo to the capital are to be in accordance with regulations [regarding the total number of escorting samurai and related matters]. 8) The samurai of the various domains shall lead a frugal and simple life. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

There was little tolerance for criminals and lawbreakers. By some counts more than 200,000 criminals and political rebels were beheaded or tied to wooden crosses at the Kozukabara execution grounds in Edo. Nearby was the bridge of tears, where the family of the condemned saw their loved ones alive for the last time.

Women in the Edo Period

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Kaibara Ekken (1630-1714) was a neo-Confucian scholar and naturalist who served the Kuroda lords of Fukuoka domain on the southern island of Kyushu. Ekken was committed to popularizing Confucian ethics and was well-known for his accessible self-help guides — down-to-earth manuals of behavior written in vernacular Japanese rather than in difficult scholarly language. Ekken’s treatises included volumes delineating proper conduct for lords, warriors, children, families, and, perhaps most famously, women. In “Onna daigaku” (“The Great Learning for Women”) Ekken promotes a strict code of behavior for mothers, wives, and daughters very much in harmony with the neo- Confucian intellectual orthodoxy of Tokugawa Japan. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Excerpts from The Great Learning for Women (Onna Daigaku) by Kaibara Ekken: “It is the duty of a girl living in her parents’ house to practice filial piety toward her father and mother. But after marriage, her duty is to honor her father-in-law and mother-in-law, to honor them beyond her father and mother, to love and reverence them with all ardor, and to tend them with a practice of filial piety. While thou honorest thine own parents, think not lightly of thy father-in-law! Never should a woman fail, night and morning, to pay her respects to her father-in-law and mother-in-law. Never should she be remiss in performing any tasks they may require of her. With all reverence she must carry out, and never rebel against, her father-in-law’s commands. On every point must she inquire of her father-in-law and mother-in- law and accommodate herself to their direction. Even if thy father-in-law and mother-in-law are disposed to hate and vilify thee, do not be angry with them, and murmur not. If thou carry piety toward them to its utmost limits and minister to them in all sincerity, it cannot be but that they will end by becoming friendly to thee. [Source: [“Onna daigaku,” in NST, vol. 34, pp. 202–5; trans. adapted and revised from Chamberlain, “Educational Literature of Japanese Women,” pp. 325.43; WtdB; “Sources of Japanese Tradition”, edited by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Carol Gluck, and Arthur L. Tiedemann, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 263-271]

“A woman has no other lord; she must look to her husband as her lord and must serve him with all worship and reverence, not despising or thinking lightly of him. The Way of the woman is to obey her man. In her dealings with her husband, both the expression of her countenance and the style of her address should be courteous, humble, and conciliatory, never peevish and intractable, never rude and arrogant — that should be a woman’s first and principal care. When the husband issues his instructions, the wife must never disobey them. In doubtful cases she should inquire of her husband and obediently follow his commands. If her husband ever asks her a question, she should answer to the point; to answer carelessly would be a mark of rudeness. If her husband becomes angry at any time, she must obey him with fear and trembling and not oppose him in anger and forwardness. A woman should look on her husband as if he were Heaven itself and never weary of thinking how she may yield to him and thus escape celestial castigation.

19th century geisha

“A woman must always be on the alert and keep a strict watch over her own conduct. In

the morning she must rise early and at night go late to rest. Instead of sleeping in the middle of

the day, she must be intent on the duties of her household; she must not grow tired of weaving,

sewing, and spinning. She must not drink too much tea and wine, nor must she feed her eyes

and ears on theatrical performances (kabuki, jōruri), ditties, and ballads...In her capacity as a wife, she must keep her husband’s household in proper order. If the wife is evil and profligate, the house will be ruined. In everything she must avoid extravagance, and in regard to both food and clothes, she must act according to her station in life and never give in to luxury and pride.

“The five worst infirmities that afflict women are indocility, discontent, slander, jealousy, and silliness. Without any doubt, these five infirmities are found in seven or eight of every ten women, and it is they that cause women to be inferior to men. A woman should counteract them with self.inspection and self reproach. The worst of them all and the parent of the other four is silliness. A woman’s nature is passive (yin). The yin nature comes from the darkness of night. Hence, as viewed from the standard of a man’s nature, a woman’s foolishness [means that she] fails to understand the duties that lie before her very eyes, does not recognize the actions that will bring blame on her own head, and does not comprehend even those things that will bring calamity to her husband and children. Nor when she blames and accuses and curses innocent persons or when, in her jealousy of others, she thinks only of herself, does she see that she is her own enemy, alienating others and incurring their hatred. Lamentable errors. Again, in the education of her children, her blind affection induces an erroneous system. Such is the stupidity of her character that it is incumbent on her, in every detail, to distrust herself and obey her husband.

Hair and Cosmetics in Japan in the Edo Period

Japanese women generally wore their hair long and straight until the late 16th century. The practice of tying the hair up geisha-style with combs, ornaments, and knitting-needle-like hairpins was not a common practice until the Edo Period (1603-1867) when women began imitating the hairstyles of men, and the kind of hairstyle a woman wore often indicated her class and marriage status.

The Osafune hairstyle, with the hair sticking out and pointing down like insect antennas was worn by fashionable wives or mistresses. The butterfly-like Yoko-hyogo was worn by courtesans. Girls wore their hair like geishas in a hairstyle called Momoware. Unmarried women wore shimadamage hairstyle. The Taka-Shimada style, worn by brides today, was originally worn by the high-ranking servants of samurai.

In the Edo Period (1603-1867) there basically only three colors for make-up: white for face powders, black for eyebrows and teeth and beni for lips. In the Edo period when women married they shave off their eyebrows.

In the 19th century women painted their teeth black, a custom that was considered to make them attractive. Women painted their teeth with a layer of logwood, a dye made with rice vinegar and pieces of iron and was the same material use to make the base for Japanese lacquerware. Women shaved their eyebrows and blackened teeth, some believe, to hide their natural expression.

In the old days, the red lips of geishas was not made with lipstick but rather with rouge that was kept in a bowl and applied with a brush. Edo period woodblock prints show women applying it. Many Japanese women used beni, material made from flowers that looks green when dry bit almost magically turns bright red when water is applied to it.

Sometimes the beni was applied in such thick coatings it looked noticeably green. Beni is still sold by the Japanese cosmetics company Isehand, It is worn mostly by women who wear kimonos and is said to have a lighter and more natural feel than lipstick and is better at bringing out the natural color of one’s lips. A jar a high quality beni, enough for 40 or 50 applications, sell for around $100. One of the main reason it is so expensive is that it requires enormous amounts fo safflower to make.

Justice and Education in Japan in the Edo Period

In the Edo period, legal matters were taken care of at kujiyado (litigation inns). The owners of these inns were the equivalent of lawyers. Mostly they dealt with disputes over money. Of the 35,000 civil suits that were addressed in 1718, about 33,000 of them involved money.

In feudal Japan provincial lords set up special schools for samurai and rural communities operated schools for wealthier members of the merchant and farming class.

In the Edo period, children from age 7 to 15 attended neighborhoods temple schools run by Buddhist sects. They were taught to read, write and use an abacus. Most were taught by priests or monks but samurai, doctors and people in other professions also served as teachers. Generally there was no set tuition. Students paid what the could. The schools were so widespread that by some estimates the literacy rate in Tokyo was 80 percent. In the countryside there were not so many schools but rural people were motivated to learn to read and write so they wouldn't be cheated by tax collectors.

Economy in Japan in the Edo Period

The long period of peace, allowed economic growth to take place. An early consumer society took hold. There were lots of street vendors, selling all sorts of things. Craftsmen were able to find buyers for their products. Tea shops and restaurants opened as people began to eat out more.

Cheaper varieties of lamp oil became available and people stay up later at night. The distribution of sugar was increased and a large variety of confectionaries became available.

People read bestselling books and bought name brand items. Yuzen-zome dyed textiles were highly sought after in the 18th century. Even though Japan was largely closed to outsiders, wealthy Japanese greatly desired clothe made from foreign materials. There were entire quarters devoted to the needs of wealthy samurai and rising merchants. Men who could afford it indulged themselves with things like silk underwear with red and white flowers.

Edo (Tokyo)

Rise of the Merchant Class in Japan

The merchant class grew and prospered. As the merchant class grew richer their power grew. As the daimyo grew poorer they lost their power. By the 1800s, the revenues a once powerful daimyo made from selling rice was about that of a single kimono shop in Tokyo. The samurai under the daimyos became impoverished and had to seek other lines of work, such as working as policemen and craftsmen. Many were forced to beg or sell their swords to eat.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Although merchants were accorded low social status in the Tokugawa order and the Confucian orthodoxy of the time, commerce thrived in early modern Japan. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

One of the most respected figures today from the Edo period is Uesugi Yozan, a feudal lord in what is now Yamagata Prefecture. He is credited with turning his debt-ridden domain into one of the most productive regions in Japan by developing new rice paddy fields, cultivating lacquer trees and safflower, and encouraging samurai to take up farming. He is famous for implementing belt-tightening measures such as recommending that people eat simple meals and wear cotton clothes. He described his policies and reasoning behind them in Denkoku no Ji, a book on how feudal lords should think and behave. In moderns Japan this book and Uesugi’s ideas and methods has drawn the interest of business executives and local administrators and bureaucrats.

Merchant House Code: The Code of the Okaya House (1836)

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Beginning in the seventeenth century, merchant houses (and especially those of wealth and age) began issuing codes, essentially lists of instructions intended for later generations to follow. These written codes echoed the military house codes that had a much longer history in Japan. The Okaya house was based in Nagoya in central Japan and had its origins trading in hardware. This code was written by Okaya Sanezumi, under whose leadership the house prospered, in 1836. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Codes of Merchant Houses: The Code of the Okaya House (1836): 1) Remember your duties to your parents. We cannot distinguish between cause and effect unless we remember that our parents are the “cause” of our existence. Neither can we make filial piety the “cause” of our actions unless we remember the debt of gratitude we owe our parents. [Source: Yoshida, ed., “Shōka no kakun,” pp. 114–24; trans. adapted from Ramseyer, “Thrift and Diligence,” pp. 227–30; “Sources of Japanese Tradition”, edited by Wm. Theodore De Bary, Carol Gluck, and Arthur L. Tiedemann, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 313 ]

2) Honor your superiors. Everyone, young or old, should consider the distinctions between master and servant and between superior and inferior to be basic, and so honor those above him.

Edo

3) Maintain peace within the neighborhood. Peace in a neighborhood depends on peace in each house, but peace in a house depends on the attitudes of its members. If each person in your house maintains a healthy attitude and works faithfully, everyone will be on good terms with his colleagues, and your house will win the respect of the neighborhood.

4) Instruct your descendants. Teach your children when they are young to lead pure lives. Teach them to obey their parents, to respect their elders, never to tell even a small lie, to move about quietly, never to neglect their work, to be always alert, never to walk about aimlessly, and never to dress or eat extravagantly.

5) Be content with your Way. Samurai study the martial arts and work in the government. Farmers till their lands and pay their taxes. Artisans work at their family industries and pass on to their children the family traditions. Merchants have trading as their duty and must trade diligently and honestly. Each of the four classes has its own Way, and that Way is the true Way.

6) Avoid bad behavior. Although the world is limitless, everything in it is either good or bad. That which follows the Way is good, while that which goes against it is bad.

Edo Period and the Beginning of Japan’s Large Corporations

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Tokugawa period was a time of dynamic commercial growth. At the center of this was the merchant class. Although socially the merchants had less prestige then other classes, they held great economic power. A number of the great Japanese multi-national corporations of today came from simple beginnings in the Tokugawa period. [Source:Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Mitsui Takatoshi (1622-1694), founder of the Mitsui empire, said: "A great peace is at hand. The shôgun rules firmly and with justice at Edo. No more shall we have to live by the sword. I have seen that great profit can be made honorably. I shall brew sake and soy sauce and we shall prosper." [Source: Translation by Carol Gluck, George Sansom Professor of Japanese History, Columbia University]

Carol Gluck of Columbia University said: In the Edo Period there was “tremendous commercialization. The penetration of the money economy. The urbanization — and towns are so important to commerce — the what some scholars now like to call "proto-industrialization," "proto-capitalism," — all these "protos," which is just by way of saying that there were a lot of changes that became capitalism and industrialization, all that later, that seemed to be starting in the Tokugawa...There are no merchant princes in Japanese history in the Tokugawa period, which is an interesting thought. It would have to be something like a merchant feudal lord, or a merchant samurai, and that kind of coupling is not possible in Japanese history. It did not happen. What you have instead, in terms of this rise of what became the truly wealthy and prosperous and influential merchants, is simple beginnings and consistent prospering across the centuries.”

Echigo-ya, the World’s First Large-Scale Retailer

model of Echigo-ya in the Edo-Tokyo Museum

Echigo-ya, a kimono store that was the predecessor of Mitsukoshi department store, was the world’s first large-scale retailer and the biggest store throughout the 18th century, according to a study by Japanese and French scholars. According to an article published in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “ Echigo-ya started business in Edo, today’s Tokyo, in 1673 during the Edo period (1603-1867). The latest discovery was made by Tsunehiko Yui, a researcher of business history and the curator of Mitsui Bunko, or Mitsui Archives. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, February 4, 2013 ***]

“Mitsui Bunko is known for its vast collection of historical business records and its research of such records related to the Mitsui family business conglomerate. In comparing the records of Echigo-ya with those from Europe and other regions, Yui confirmed the store’s annual sales in the 18th century were equivalent to about 10 billion yen in today’s terms. It also boasted one of the world’s largest workforces and ground area at the time. The shop employed at least 300 people and occupied an area up to about 2,400 square meters. The recent study was conducted jointly with Prof. Patrick Fridenson of France’s state-run School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, who is also a researcher of business history. The results of the two scholars' research were presented at the Japan-France business management history conference. ***

“Echigo-ya introduced a new sales formula in Japan of "cash payment, no discounts and no markups," in its sales of kimono and other merchandise to a wide range of ordinary people. The shop’s business grew rapidly. According to ledgers stored at Mitsui Bunko, in the 10-year period from 1739, Echigo-ya’s annual sales amounted to 200,000 ryo. One ryo is equivalent to between 40,000 yen and 60,000 yen today.According to Fridenson, who specializes in comparing business management history across nations, Europe’s storefront retailers developed in the 18th century but on a smaller scale.Thus they concluded there was no retail establishment on the same scale as Echigo-ya during the time period. ***

“The researchers said it was not until the 19th century when such large-scale retailers as French department stores Le Bon Marche and Printemps appeared on the continent. Yui said: "In the 18th century, people talked about Paris or London as the center of the world economy. But Edo had already developed as one of the world’s largest cities with a population of nearly 1 million. I assume the development of traffic networks and a growing number of consumers also contributed to the growth of large-scale retailers." ***

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Ukiyo- from Library of Congress, British Museum, and Tokyo National Museum, Old photos from Visualizing Culture, MIT Education; mummy: National Museum of Science, Tokyo

Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016