EARLY HISTORY OF SINGAPORE

The origins of what became Singapore are unclear.Some historians believe that a town was founded on Singapore Island as early as the seventh century, while other sources claim that "Singapura" (Lion City) was established by an Indian prince in 1299. A third century Chinese account describes it as "Pu-luo-chung", or the "island at the end of a peninsula". Later, the city was known as Temasek ("Sea Town"), when the first settlements were established from AD 1298-1299. During the 13th and 14th centuries, historians believe a thriving trading center existed until it was destroyed by a Javanese attack in 1377. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007; YourSingapore.com, Singapore Tourism Board; N. Prabha Unnithan, World Press Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

During the seventh century, when a succession of maritime states arose throughout the Malay Archipelago, what is nows Singapore probably was one of the many trading outposts serving as an entrepôt and supply point for Malay, Thai, Javanese, Chinese, Indian, and Arab traders. A fourteenth-century Javanese chronicle referred to the island as Temasek ("Sea Town"), and a seventeenth-century Malay annal noted the 1299 founding of the city of Singapura (“lion city”) after a strange, lion-like beast that had been sighted there. Singapura was controlled by a succession of regional empires and Malayan sultanates.

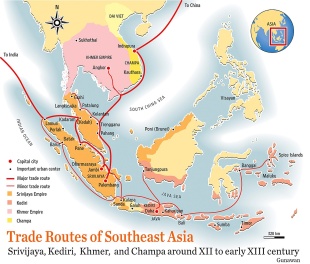

In time, the ports of the peninsula and archipelago formed the nucleus of a succession of seabased kingdoms, empires, and sultanates. By the late seventh century, the great maritime Srivijaya Empire, with its capital at Palembang in eastern Sumatra, had extended its rule over much of the peninsula and archipelago. Historians believe that the island of Singapore was probably the site of a minor port of Srivijaya. Temasek and Singapura. For a time Singapore was a small Malay fishing village that belonged to the Sultan of Johor and was part of the powerful 15thand 16th century Malacca sultanate..

RELATED ARTICLES:

SINGAPORE HISTORY: NAMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE EARLY 1800s: BRITAIN, RAFFLES AND HIS PLAN factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE GROWS AND PROSPERS IN THE 19TH CENTURY: TRADE, THE BRITISH, IMMIGRANTS factsanddetails.com

CHINESE, MALAYS AND INDIANS IN EARLY SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

JAPAN'S MALAYA CAMPAIGN AND DEFEAT OF THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE INVASION OF SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE DURING WORLD WAR II: POOR BRITISH DEFENSE, HARSH JAPANESE OCCUPATION factsanddetails.com

Early Accounts of Singapore

Although legendary accounts shroud Singapore's earliest history, chroniclers as far back as the second century alluded to towns or cities that may have been situated at that favored location. Some of the earliest records of this region are the reports of Chinese officials who served as envoys to the seaports and empires of the Nanyang (southern ocean), the Chinese term for Southeast Asia. The earliest first-hand account of Singapore appears in a geographical handbook written by the Chinese traveler Wang Dayuan in 1349. Wang noted that Singapore Island, which he called Tan-ma-hsi (Danmaxi), was a haven for several hundred boatloads of pirates who preyed on passing ships. He also described a settlement of Malay and Chinese living on a terraced hill known in Malay legend as Bukit Larangan (Forbidden Hill), the reported burial place of ancient kings. The fourteenth-century Javanese chronicle, the Nagarakertagama, also noted a settlement on Singapore Island, calling it Temasek. [Source: Library of Congress *]

A Malay seventeenth-century chronicle, the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), recounts the founding of a great trading city on the island in 1299 by a ruler from Palembang, Sri Tri Buana, who named the city Singapura ("lion city") after sighting a strange beast that he took to be a lion. The prosperous Singapura, according to the Annals, in the mid-fourteenth century suffered raids by the expanding Javanese Majapahit Empire to the south and the emerging Thai kingdom of Ayutthaya to the north, both at various times claiming the island as a vassal state. *

The Annals, as well as contemporaneous Portuguese accounts, note the arrival around 1388 of King Paramesvara from Palembang, who was fleeing Majapahit control. Although granted asylum by the ruler of Singapura, the king murdered his host and seized power. Within a few years, however, Majapahit or Thai forces again drove out Paramesvara, who fled northward to found eventually the great seaport and kingdom of Malacca. In 1414 Paramesvara converted to Islam and established the Malacca Sultanate, which in time controlled most of the Malay Peninsula, eastern Sumatra, and the islands between, including Singapura. Fighting ships for the sultanate were supplied by a senior Malaccan official based at Singapura. The city of Malacca served not only as the major seaport of the region in the fifteenth century, but also as the focal point for the dissemination of Islam throughout insular Southeast Asia.

Legend of Sang Nila Utama

According to legend, Sang Nila Utama, a prince from Palembang—the capital of the Srivijaya empire—was on a hunting expedition when he encountered an animal he had never seen before. Interpreting the sighting as a favorable omen, he founded a settlement in 1299 at the place where the animal appeared and named it “Singapura,” or “The Lion City,” from the Sanskrit words simha (lion) and pura (city). At the time, the city was said to be ruled by the five kings of ancient Singapura. Situated at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, a natural crossroads of maritime routes, Singapura flourished as a trading port, hosting vessels ranging from Chinese junks and Indian ships to Arab dhows, Portuguese warships, and Buginese schooners.

Sang Nila Utama—whose name literally means “main indigo”—was formally styled Sri Maharaja Sang Utama Parameswara Batara Sri Tri Buana, meaning “Lord Central King Batara of the Three World Realms,” signifying authority over Palembang, Bintan, and Singapura. He consolidated his rule by forging strong ties with China and was officially recognized as ruler of Singapore by a Chinese imperial envoy in 1320. He died in 1347 and was succeeded by his son, Paduka Seri Wikrama Wira. [Source: Wikipedia]

A longer version of the legend recounts that, in search of a suitable site for a new city, Sang Nila Utama sailed with a fleet from Palembang to the islands off the coast of southern Sumatra. After reaching the Riau Islands and being welcomed by their queen, he went hunting on a nearby island. While chasing a deer up a hill, the animal vanished, leading him instead to a large rock. From its summit, he gazed across the sea and noticed an island with a white sandy beach that resembled a white cloth. When he asked his chief minister about it, he was told the island was Temasek, and he decided to visit it.

As his ship set out, a violent storm arose, tossing the vessel and causing it to take on water. To save the ship, his men threw heavy objects overboard, but the flooding continued. Acting on the advice of the ship’s captain, who claimed the storm was caused by Sang Nila Utama’s grandfather, the Lord of the Sea, he cast his crown into the water as an offering. The storm immediately subsided, and he reached Temasek safely. Another version of the legend suggests that the crown was simply too heavy for the ship.

Landing near the mouth of what is now the Singapore River, Sang Nila Utama ventured inland to hunt. There he saw a striking animal with an orange body, black head, and white breast that moved swiftly before disappearing into the forest. His chief minister identified it as a lion. Modern studies, however, indicate that lions never inhabited Singapore, leading some scholars to suggest the animal was more likely a Malayan tiger. Others argue that tigers were common in ancient Southeast Asia and would have been easily recognized, proposing instead that the creature was mythical—a guardian spirit of Temasek.

Taking the sighting as an auspicious sign, Sang Nila Utama resolved to establish his city on the island. He and his followers settled there in 1324 and renamed Temasek “Singapura.” The name combines singa, the Malay word for lion (derived from the Sanskrit singha), and pura, meaning town or city. Sang Nila Utama ruled Singapura for forty-eight years, strengthened diplomatic relations with China, and was again formally recognized by a Chinese imperial envoy in 1366. He was said to have been buried at the foot of Bukit Larangan (present-day Fort Canning Hill), possibly beside his wife, though no confirmed tomb has ever been found. Some believe his remains may instead lie at the shrine known as Keramat Iskander Shah.

Trade in 14th-15th -Century -Singapore

Singapore was strategically located at the junction of the Malacca Straits and the South China Sea at the southern tip of what is now Southeast Asia. Maritime trade carried on Arab dhows, Portuguese ships, Chinese junks and Buginese prabus between China, Japan and the Spice Islands in the Far East and India, Europe and the Middle East to the west all sailed by. In the 14th century it was known on some charts as Temask ("Sea Town"). Singapore was a trading center in the large, Sumatra-centered Srivijaya Empire (A.D. 7th and 13th centuries) it was destroyed in the 14th century by the Java-based Majapahit empire. It later became part of Johore in the Malacca Sultanate.

Located astride the sea routes between China and India, from ancient times the Malay Archipelago served as an entrepôt, supply point, and rendezvous for the sea traders of the kingdoms and empires of the Asian mainland and the Indian subcontinent. Singapore sits on the Strait of Malacca, according to Archaeology magazine, a narrow channel in the Malay-Indonesian archipelago that connects the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. Situated at the junction of two monsoons, the strait necessitated a long layover for ships dependent on seasonal winds. The region’s premier entrepôt at the time was Melaka, where traders from Arabia and India would stop over until the next monsoon wind took them farther north to China, or back south laden with silks and spices. [Source: Vaishnavi Chandrashekhar, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2017]

The trade winds of the South China Sea brought Chinese junks laden with silks, damasks, porcelain, pottery, and iron to seaports that flourished on the Malay Peninsula and the islands of Sumatra and Java. There they met with Indian and Arab ships, brought by the monsoons of the Indian Ocean, carrying cotton textiles, Venetian glass, incense, and metalware. Fleets of swift prahu (interisland craft) supplied fish, fruit, and rice from Java and pepper and spices from the Moluccas in the eastern part of the archipelago. All who came brought not only their trade goods but also their cultures, languages, religions, and technologies for exchange in the bazaars of this great crossroads. [Source: Library of Congress]

According to Archaeology magazine: Two shipwrecks dating to the period when Singapore was a key stop on the trade route connecting the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea were discovered in the waters near the outlying island of Pedra Branca. The older of the 2 ships sank in the 14th century. The other has been identified as Shah Munchah, an Indian-built ship that wrecked in 1796. It carried a huge cargo of Chinese ceramics and blue-and-white Yuan Dynasty porcelain destined for Great Britain. [Source: Archaeology Magazine, September 2021]

See Maritime Silk Road factsanddetails.com

Archaeology That Reveals Singapore’s Glorious 14th-15th Century Past

The historical narrative that says Singapore was nothing but a fishing village before 1819 has been revised. Vaishnavi Chandrashekhar wrote in Archaeology magazine: Largely due to archaeological excavations that began in 1984 and culminated in the island’s largest-ever dig, in 2015, evidence now exists of a fourteenth-century port city that had long been buried under downtown Singapore. Led by American archaeologist John Miksic and more recently by Singaporean archaeologist Lim Chen Sian, a researcher with the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Archaeology Unit at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, these rescue digs have revealed fragments of earthenware, Chinese pottery, Indian beads, and Javanese jewelry that date to between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. [Source:Vaishnavi Chandrashekhar, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2017]

In the 1980s, Miksic was involved in excavations within Singapore’s Fort Canning Park. The fort was built in 1859 on the leveled summit of a small hill downtown, known in Raffles’ time as Forbidden Hill, and host to a tomb or memorial purportedly of the last king. Parts of the site were undisturbed and the stratification layers were clear. Archaeologists found sherds of Chinese pottery — both imported and locally made — and coins of the Song and Tang Dynasties. Miksic recalls being taken by complete surprise. Although there were records of Temasek in Chinese writings, there had always been arguments over its location. And the Malay Annals were considered a romance — to the extent that even Miksic’s Cornell adviser believed the Singapura story to be a fabrication. “The idea that the Annals were closely paralleled by reality was not taken seriously by historians,” says Miksic. “We had no clue until we found this stuff.”

Miksic went on to lead 10 more digs at Fort Canning after moving to Singapore in 1987, and undertook another 10 to 15 excavations along the Singapore River. The sites were chosen serendipitously — all were rescue digs carried out quickly when a building was knocked down or a parking garage chosen for development. The finds, in total, included 10,000 Indian and Javanese glass beads, Indian bangles and other pieces of jewelry, and 500,000 pieces of pottery, some of which are still being sorted. Chinese and Sri Lankan coins found along the riverbank speak to the high volume of trade, and Chinese glass beads and vessels, as well as the fragment of a rare porcelain pillow and a unique compass bowl, all suggest an exceptionally close relationship with China.

Significantly, a substantial amount of locally made household pottery was also found. Because cooking pots are unlikely to be imported, their presence indicates a settled community rather than a city of transients. The quantity and style of pots can also provide clues to the cultural affiliations of residents and the sizes of settlements in different parts of the old city. Some of the forms of pottery found, Miksic says, “enable us to certify that the local inhabitants were culturally related to those of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, rather than Java.”

Taken together, the finds reveal that Singapore was a major trade hub by 1350, importing and exporting between India, Southeast Asia, and China. It was fortified — rare for the time — used currency, and likely hosted a multiethnic population governed by a local chief. Miksic says evidence suggests that it was not a political power or ceremonial center, but was perhaps like contemporaneous port towns of the Mediterranean. There was little agriculture, and services were the mainstay. Singapore procured raw materials such as iron, as well as porcelain, tortoiseshell, glass, and beads, from a network of suppliers. “The archaeology of Singapore confirms what we thought we knew from local chronicles such as the Malay Annals and Chinese texts,” says Miksic, “while adding much more detail about the types of objects traded and the complexity of the economy of even a medium-sized port.” He adds, “We are also beginning to see what a place with a strong Chinese influence would have looked like.”

Singapore’s golden age lasted almost a century. There are almost no artifacts from the fifteenth century, when the city was likely conquered and the trade hub moved to Melaka. But Singapore continued to be a transit point for ships — Saint Francis Xavier wrote a letter while docked here in 1551 — before it was finally abandoned in the seventeenth century. According to Miksic, the Dutch policy of forcing traders to call at Batavia (today’s Jakarta) may be partly responsible, but trade in Asia also contracted in this period.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Lion City's Glorious Past” by Vaishnavi Chandrashekhar, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2017archaeology.org

Early European Presence in the Singapore Area

Portuguese explorers captured the port of Melaka (Malacca)—not far from present-day Singapore—in 1511, forcing the reigning sultan to flee south, where he established a new regime, the Johore Sultanate, that incorporated Singapura. The Portuguese burned down a trading post at the mouth of the Temasek (Singapore) River in 1613; after that, the island was largely abandoned and trading and planting activities moved south to the Riau Islands and Sumatra. However, planting activities had returned to Temasek by the early nineteenth century.

By the early seventeenth century, both the Dutch and the English were sending regular expeditions to the East Indies. The English soon gave up the trade, however, and concentrated their efforts on India. In 1641 the Dutch captured Malacca and soon after replaced the Portuguese as the preeminent European power in the Malay Archipelago. From their capital at Batavia on Java, they sought to monopolize the spice trade. Their short-sighted policies and harsh treatment of offenders, however, impoverished their suppliers and encouraged smuggling and piracy by the Bugis and other peoples. By 1795, the Dutch enterprise in the East was losing money and, in Europe, the Netherlands was at war with France. The Dutch king fled to Britain where, in desperation, he issued the Kew Letters, by which all Dutch overseas territories were temporarily placed under British authority in order to keep them from falling to the French.

Although the region came under the control of European maritime empires after the Portuguese acquired Melaka in 1511, Singapore's rapid development beginning in the nineteenth century must be seen as an expansion of existing Asian internal and external trade. After Guangdong, China, was opened to European trade in 1757, the British East India Company's tea trade with China increased. [Source: History of World Trade Since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2006.]

Singapore and the Johore Sultanate

When the Portuguese captured Malacca in 1511, the reigning Malaccan sultan fled to Johore in the southern part of the Malay Peninsula, where he established a new sultanate. Singapura became part of the new Johore Sultanate and was the base for one of its senior officials in the latter sixteenth century. In 1613, however, the Portuguese reported burning down a trading outpost at the mouth of the Temasek (Singapore) River, and Singapura passed into history. [Source: Library of Congress]

In the following two centuries, the island of Temasek was largely abandoned and forgotten as the fortunes of the Johore Sultanate rose and fell. By 1722 a vigorous seafaring people from the island of Celebes (modern Sulawesi, Indonesia) had become the power behind the throne of the Johore Sultanate. Under Bugis influence, the sultanate built up a lucrative entrepôt trade, centered at Riau, south of Singapore, in present-day Sumatra. Riau also was the site of major plantations of pepper and gambier, a medicinal plant used in tanning. The Bugis used waste material from the gambier refining process to fertilize pepper plants, a valuable crop, but one that quickly depletes soil nutrients. By 1784 an estimated 10,000 Chinese laborers had been brought from southern China to work the gambier plantations on Bintan Island in the Riau archipelago (now part of Indonesia). In the early nineteenth century, gambier was in great demand in Java, Siam, and elsewhere, and cultivation of the crop had spread from Riau to the island of Singapore. *

The territory controlled by the Johore Sultanate in the late eighteenth century was somewhat reduced from that under its precursor, the Malacca Sultanate, but still included the southern part of the Malay Peninsula, the adjacent area of Sumatra, and the islands between, including Singapore. The sultanate had become increasingly weakened by division into a Malay faction, which controlled the peninsula and Singapore, and a Bugis faction, which controlled the Riau Archipelago and Sumatra. When the ruling sultan died without a royal heir, the Bugis had proclaimed as sultan the younger of his two sons by a commoner wife. The sultan's elder son, Hussein (or Tengku Long) resigned himself to living in obscurity in Riau. *

Although the sultan was the nominal ruler of his domain, senior officials actually governed the sultanate. In control of Singapore and the neighboring islands was Temenggong Abdu'r Rahman, Hussein's father-in-law. Singapore's last sultan died 1835. He ruled Singapore and parts of southern Malaysia until he formally ceded them to the British in 1824. More than 200 of the sultan’s relatives continued to live in his palace until they were thrown out in 1999.

Early British Presence in Singapore

In the late eighteenth century, the British began to expand their commerce with China from their bases in India through both private traders and the British East India Company. The company had occupied a small settlement at Bencoolen (Bengkulu) on the western coast of Sumatra since 1684; from there it had engaged in the pepper trade after being forced out of Java by the Dutch. Acutely aware of the need for a base somewhere midway between Calcutta and Guangzhou, the company leased the island of Penang, on the western coast of the Malay Peninsula, from the sultan of Kedah in 1791.

Thomas Stamford Raffles arrived in 1819 while searching for a trading location along the Strait of Malacca that would be free from Dutch influence. He established a trading station in Singapore, which came under British control in 1824. Two years later, Singapore, Penang, and Malacca became a British colony known as the Straits Settlements. [Source: History of World Trade Since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2006]

In the early 1800s, Singapore was known for its tiger-infested jungles and pirate-ridden seas. It was a mostly-uninhabited swampy island surrounded by small islands occasionally used by pirates. Sentosa, an island that now has several theme parks, used to be known as Pulau Blakang Mati (the island in front of death) because pirate launched attacks from it. In 1818 Temasek was settled by a Malay official of the Johore Sultanate and his followers, who shared the island with several hundred indigenous tribal people and Chinese planters.

Anglo-Dutch Competition Over Singapore

In the early 19th century, Singapore was an up and coming trading post along the Malacca Straits, and Britain realised the need for a port of call in the region. British traders needed a strategic venue to refresh and protect the merchant fleet of the growing empire, as well as forestall any advance made by the Dutch in the region.

In 1818, before Raffles arrived in what is now Singapore, the temenggong (a high Malay official) and some of his followers left Riau for Singapore shortly after the Dutch signed a treaty with the Bugis-controlled sultan, allowing them to station a garrison at Riau. The temenggong's settlement on the Singapore River included several hundred orang laut (sea gypsies in Malay) under Malay overlords who owed allegiance to the temenggong. For their livelihood the inhabitants depended on fishing, fruit growing, trading, and occasional piracy. Large pirate fleets also used the strait between Singapore and the Riau Archipelago as a favorite rendezvous. Also living on the island in settlements along the rivers and creeks were several hundred indigenous tribespeople, who lived by fishing and gathering jungle produce. Some thirty Chinese, probably brought from Riau by the temenggong, had begun gambier and pepper production on the island. In all, perhaps a thousand people inhabited the island of Singapore at the dawn of the colonial era. *

From their posts at Penang and Bencoolen, the British began in 1795 to occupy the Dutch possessions placed temporarily in their care by the Kew Letters, including Malacca and Java. After war in Europe ended in 1814, however, the British agreed to return Java and Malacca to the Dutch. By 1818 the Dutch had returned to the East Indies and had reimposed their restrictive trade policies. In that same year, the Dutch negotiated a treaty with the Bugis-controlled sultan of Johore granting them permission to station a garrison at Riau, thereby giving them control over the main passage through the Strait of Malacca. British trading ships were heavily taxed at Dutch ports and suffered harassment by the Dutch navy. Meanwhile, the British government and the British East India Company officials in London, who were concerned with maintaining peace with the Dutch, consolidating British control in India, and reducing their commitments in the East Indies, considered relinquishing Bencoolen and perhaps Penang to the Dutch in exchange for Dutch territories in India.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Singapore Tourism Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026