SINGAPORE GROWS AND PROSPERS

In 1819, the British East India Company leased parts of what became Singapore from the Sultan of Johore to establish a trade and communication post, the area was a small settlement in a swampy region. However, the British administration quickly cleared the jungle, reclaimed the marshes, and established a merchant seaport. Due to its strategic and convenient location along the main sea route connecting the Far East to British India and Europe, this port expanded into a major regional trading post. Singapore's rise as a communication hub would lay the groundwork for its future prosperity.[Source: Rafis Abazov, Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

Following Sir Thomas Raffles’s establishment of his free-trade port, Singapore grew in size, population, and prosperity. In 1824 the Dutch formally recognized British control of Singapore, and London acquired full sovereignty over the island. In 1832, Singapore became the centre of government for the Straits Settlements of Penang, Malacca and Singapore. From 1826 to 1867, Singapore, along with two other trading ports on the Malay Peninsula—Penang and Malacca—and several smaller dependencies, were ruled together as the Straits Settlements from the British East India Company headquarters in India.

In the first half-century after its founding, Singapore grew from a precarious trading post of the British East India Company populated by a few thousand to a bustling, cosmopolitan seaport of 85,000. Although the general trend of Singapore's economic status was upward during this period, the settlement endured economic recessions as well as prosperity, fires and floods as well as building booms, and bureaucratic incompetence as well as able administration. In 1826 the British East India Company combined Singapore with Penang and Malacca to form the Presidency of the Straits Settlements, with its capital at Penang. The new bureaucratic apparatus proved to be expensive and cumbersome, however, and in 1830 the Straits Settlements were reduced to a residency, or subdivision, of the Presidency of Bengal. Although Singapore soon overshadowed the other settlements, Penang remained the capital until 1832 and the judicial headquarters until 1856. The overworked civil service that administered Singapore remained about the same size between 1830 and 1867, although the population quadrupled during that period. Saddled with the endless narrative and statistical reports required by Bengal, few civil servants had time to learn the languages or customs of the people they governed. [Source: Library of Congress]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SINGAPORE HISTORY: NAMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

EARLY HISTORY OF SINGAPORE: LEGENDS, ARCHAEOLOGY AND 14TH CENTURY TRADE factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE EARLY 1800s: BRITAIN, RAFFLES AND HIS PLAN factsanddetails.com

CHINESE, MALAYS AND INDIANS IN EARLY SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

JAPAN'S MALAYA CAMPAIGN AND DEFEAT OF THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE INVASION OF SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE DURING WORLD WAR II: POOR BRITISH DEFENSE, HARSH JAPANESE OCCUPATION factsanddetails.com

Trade in 19th Century Singapore

Singapore quickly became a major shipping hub, especially for merchant ships traveling between India and China. Materials produced in Southeast Asia and shipped through the area included spices, gold, resins, rare gums, and other products from the region’s rainforests, mines, and plantations. When Raffles founded Singapore, he intended for it to remain a free port, so he imposed no import or export duties, wharf fees, marine or port dues, or other charges on shipping. The movement of goods and people in and out of the port was not regulated. With some minor exceptions, Singapore remained a free port until the latter half of the twentieth century. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Thomson Gale, 2008]

The initial phase of Singapore's commercial development accommodated local and Asian enterprise, with the Chinese dominating the scene. The Bugis, for instance, were important carriers; from their headquarters in the Celebes (present-day Sulawesi, Indonesia), they made their way in sailing boats called prahus, collecting and distributing the produce of the eastern half of the archipelago to Singapore and taking away in exchange European and Indian textiles and other products. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Singapore's economy was primarily based on its role as an entrepôt for neighboring countries, thanks to its strategic location at the entrance to the Strait of Malacca. It lacked minerals and other primary products of its own to export and it served a major economic function by processing and transshipping goods from nearby lands. Singapore became highly active in shipbuilding and repair, tin smelting, and rubber and copra milling. However, until around 1960, its economy was frequently shaken by major fluctuations in export earnings, particularly from rubber and tin, due to adverse commodity and price trends. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

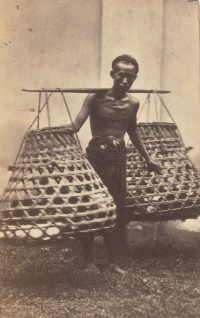

Chinese, Indians and Other Groups Flow Into Singapore

The lucrative trade activity in Singapore attracted settlers from the Malay Peninsula and India, as well as large numbers of merchants, craftsmen, and planters from China. As trade increased and infrastructure developed under British rule, migrant workers—many of them Chinese and Indian, from what is now Sri Lanka—began arriving to join the indigenous Malays. The island became a rich blend of colors, religions—including Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Confucianism, Christianity, and Hinduism—and languages, such as English, Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil. [Source: David Lamb, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2007]

By 1827 Chinese had become the most numerous of Singapore’s various ethnic groups. They came from Malacca, Penang, Riau, and other parts of the Malay Archipelago. More recent Chinese migrants came from the South China provinces of Guangdong and Fujian. After 1837 the Chinese dominated the trade of Singapore. Around this date, Singapore was recorded to have imported British manufactures to the annual amount of several hundred thousand pounds and to have attracted a polyglot population of Chinese, Malays, Indians, Javanese, Bugis, Balinese, and Arabs.[Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Over the next century, Singapore’s population grew to be predominantly Chinese. By the beginning of the 1900s, more women had joined Chinese society in Singapore, and the region became more settled as families and schools were established. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Thomson Gale, 2008]

Singapore Becomes a Flourishing Free Port

Britain's acquisition of Hong Kong in 1842 increased its trade with China. Along with the advent of steamships and telegraphs the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, Singapore's significance as a free financial and trading entrepôt, as well as a coaling station for shipping in Southeast Asia, East Asia, and the British Navy, increased. While European commercial banks established branches in Singapore, Chinese moneylenders and Hindu chettiars financed native trade. They provided Asian merchants with funds and a strong commercial base. [Source: History of World Trade Since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2006]

With its excellent harbor, Singapore became a flourishing commercial center and the leading seaport of Southeast Asia, handling the vast export trade in tin and rubber from British-ruled Malaya. The port on the island of Singapore was initially developed by the East India Company. In 1867 it was taken over by the British government. Singapore was considered Britain's key defensive position in the Far East. Trade grew because of its status as a free port. After the Suez Canal opened Singapore's importance as a centre of the expanding trade between the East and West increased tremendously. By 1860, the thriving country had a population that had grown from a mere 150 in 1819 to 80,792, comprising mainly Chinese, Indians and Malays.

With the advent of steam shipping, Singapore's advantages increased even further due to its location as a coaling depot. The expansion of steam-based commercial transport threatened to increase congestion and undermine trade, but this was averted with the development of the New Harbour (later known as Keppel Harbour), which began in earnest in the 1860s. Between 1860 and 1912, a number of companies competed against each other for contracts related to dock building and wharfing facilities. In 1912 the Singapore Harbour Board was reconstituted and the government began an extensive program of wharf accommodation and dock building. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Intra-Asia Trade in Singapore

Trade between Europe and Asia formed only one part of Singapore’s commercial activity. Equally important was intra-Asian trade, which involved large-scale exchanges with Southeast Asia, particularly in rice and fish. British political control played a significant role in driving the expansion of this regional trade. British dominance in Malaya, in particular, had a marked impact on the commerce of the Straits Settlements, whose merchants were heavily invested in Malaya’s natural resources, especially tin and rubber. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Trade with Thailand illustrates this pattern of growth. In 1870, the value of imports from and exports to Thailand was roughly equal. By 1915, however, imports had increased thirteenfold, while exports rose by only four and a half times. Thailand supplied rice to Singapore and the Straits Settlements, while Malaya exported rubber and tin.

Burma (Myanmar) played a comparatively minor role in this network. Although Burma was a major rice producer, its exports were increasingly diverted to British and European markets following the opening of the Suez Canal. Borneo, by contrast, figured prominently in Singapore’s trade. Goods such as rice, fish, cloth, opium, machinery, and railway materials were exported from Singapore to Borneo, while the port received substantial imports of rattan, gambier, sago, gum, copra, coffee, and tobacco. Other Southeast Asian products entering Singapore included Indonesian commodities such as pepper, rattan, gambier, and small quantities of rubber.

By the period between 1870 and 1915, the trade of the Straits Settlements had evolved into one largely centred on Southeast Asian produce. By the end of this era, Malaya had become Singapore’s most important trading partner, with tin and rubber dominating imports. The city’s extraordinary commercial growth was mirrored in the rapid expansion of infrastructure, including dock facilities and civic amenities, built to support its rising economic stature.

Singapore Becomes a Key Military, Administration and Immigration Center

Although the European and Asian commercial community was reasonably satisfied with the administration of the settlement under Bengal, an economic depression in the 1840s caused some to consider the merits of Singapore being administered directly as a crown colony. The advent of the steamship had made Singapore less dependent on Calcutta and more closely tied to the London commercial and political scene. By mid-century, the parent firms of most of Singapore's British-owned merchant houses were located in London rather than Calcutta.

In 1851, following a visit to Singapore, Lord Dalhousie, the governor general of India, separated the Straits Settlements from Bengal and placed them directly under his own charge. In the following sixteen years, a number of issues arose that caused increased agitation to remove the Straits Settlements completely from administration from India and place it directly under the British Colonial Office. Among these issues were the need for protection against piracy and Calcutta's continuing attempts to levy port duties on Singapore. Mostly as a result of the need for a place other than fever-ridden Hong Kong to station British troops in Asia, London designated the Straits Settlements a crown colony on April 1, 1867. [Source: Library of Congress ]

In 1867 the British needed a better location than fever-ridden Hong Kong to station their troops in Asia, so the Straits Settlements were made a crown colony and its capital Penang, ruled directly from London. The British installed a governor and executive and legislative councils. By that time, Singapore had surpassed the other Straits Settlements in importance, as it had grown to become a bustling seaport with 86,000 inhabitants.

Singapore also dominated the Straits Settlements Legislative Council. After the Suez Canal opened in 1869 and steamships became the major form of ocean transport, British influence increased in the region, bringing still greater maritime activity to Singapore. Later in the century and into the twentieth century, Singapore became a major point of disembarkation for hundreds of thousands of laborers brought in from China, India, the Dutch East Indies, and the Malay Archipelago, bound for tin mines and rubber plantations to the north.

Early Financial Success for Singapore

Singapore came into its own as a hub for the international tea trade. Trade at Singapore had eclipsed that of Penang by 1824, when it reached a total of Sp$11 million annually. By 1869 annual trade at Singapore had risen to Sp$89 million. The cornerstone of the settlement's commercial success was the entrepôt trade, which was carried on with no taxation and a minimum of restriction. The main trading season began each year with the arrival of ships from China, Siam, and Cochinchina (as the southern part of Vietnam was then known). Driven by the northeast monsoon winds and arriving in January, February, and March, the ships brought immigrant laborers and cargoes of dried and salted foods, medicines, silk, tea, porcelain, and pottery. They left beginning in May with the onset of the southwest monsoons, laden with produce, spices, tin, and gold from the Malay Archipelago, opium from India, and English cotton goods and arms. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The second major trading season began in Septeember or October with the arrival of the Bugis traders in their small, swift prahu, bringing rice, pepper, spices, edible bird nests and shark fins, mother-of-pearl, gold dust, rattan, and camphor from the archipelago. They departed carrying British manufactures, cotton goods, iron, arms, opium, salt, silk, and porcelain. By mid-century, there were more than twenty British merchant houses in Singapore, as well as German, Swiss, Dutch, Portuguese, and French firms. The merchants would receive cargoes of European or Indian goods on consignment and sell them on commission. *

Singapore's development and prosperity at mid-century were largely confined to the coast within a few kilometers of the port area. The interior remained a dense jungle ringed by a coastline of mangrove swamps. Attempts to turn the island to plantation agriculture between 1830 and 1840 had met with little success. Nutmeg, coffee, sugar, cotton, cinnamon, cloves, and indigo all fell victim to pests, plant diseases, or insufficient soil fertility. The only successful agricultural enterprises were the gambier and pepper plantations, numbering about 600 in the late 1840s and employing some 6,000 Chinese laborers.

When the firewood needed to extract the gambier became depleted, the plantation would be moved to a new area. As a result, the forests of much of the interior of the island had been destroyed and replaced by coarse grasses by the 1860s, and the gambier planters had moved their operations north to Johore. This pressure on the land also affected the habitats of the wildlife, particularly tigers, which began increasingly to attack villagers and plantation workers. Tigers reportedly claimed an average of one victim per day in the late 1840s. When the government offered rewards for killing the animals, tiger hunting became a serious business and a favorite sport. The last year a person was reported killed by a tiger was 1890, and the last wild tiger was shot in 1904. *

The main site for mercantile activity in mid-century Singapore was Commercial Square, renamed Raffles Place in 1858. Besides the European merchant houses located on the square, there were in 1846 six Jewish merchant houses, five Chinese, five Arab, two Armenian, one American, and one Indian. Each merchant house had its own pier for loading and unloading cargo; and ship chandlers, banks, auction houses, and other businesses serving the shipping trade also were located on the square. In the early years, merchants lived above their offices; but by mid-century most had established themselves in beautiful houses and compounds in a fashionable section on the east bank of the Singapore River. *

Most of the trade between the European and Asian merchants was handled by Chinese middlemen, who spoke the necessary languages and knew the needs of their customers. Many of the middlemen had trained as clerks in the European trading firms of Malacca. With their experience, contacts, business acumen, and willingness to take risks, the middlemen were indispensable to the merchants. For the Chinese middlemen, the opportunities for substantial profit were great; but so were the risks. Lacking capital, the middlemen bought large quantities of European goods on credit with the hope of reselling them to the Chinese or Bugis ship captains or themselves arranging to ship them to the markets of Siam or the eastern Malay Peninsula. If, however, buyers could not be found or ships were lost at sea, the middlemen faced bankruptcy or prison. Although the merchants also stood to lose under such circumstances, the advantages of the system and the profits to be made kept it flourishing. *

Construction of government buildings lagged far behind commercial buildings in the early years because of the lack of taxgenerated revenue. The merchants resisted any attempts by Calcutta to levy duties on trade, and the British East India Company had little interest in increasing the colony's budget. After 1833, however, many public works projects were constructed by the extensive use of Indian convict labor. Irish architect George Drumgold Coleman, who was appointed superintendent of public works in that year, used convicts to drain marshes, reclaim seafront, lay out roads, and build government buildings, churches, and homes in a graceful colonial style. *

Life in Colonial Singapore

The highly unbalanced sex ratio in Singapore contributed to a rather lawless, frontier atmosphere that the government seemed helpless to combat. Little revenue was available to expand the tiny police force, which struggled to keep order amid a continuous influx of immigrants, often from the fringes of Asian society. This tide of immigration was totally uncontrolled because Singapore's businessmen, desperate for unskilled laborers, opposed restriction on free immigration as vehemently as they resisted any restraint on free trade. Public health services were almost nonexistent, and cholera, malnutrition, smallpox, and opium use took a heavy toll in the severely overcrowded working-class areas. [Source: Library of Congress]

Philp Lim of AFP wrote: Publications kept by the Rare Materials Collection (RMC) of Singapore's National Library include European travelogues from as early as 1577, biographical accounts of daily life in Malaya and even love poems and cookbooks from a hundred years ago. "The Mem's Own Cookery Book" — meant for the wives of British administrators who established colonies around Asia at the time — features recipes to suit the tastebuds of homesick Englishmen. Recipes for spinach soup, roast hare and pigeon mingle with tips for more adventurous fare like jungle deer curry and sheep head broth. In contrast, the "Hikayat Abdullah," an 1849 biography of the father of modern Malay literature Munshi Abdullah, offered a unique perspective often missing from records largely penned by Western authors, librarian Ong said. "It offers an Asian perspective in contrast to the accounts you see from the East India company's records and the memoirs written by those officials," he stated. [Source: Philp Lim, AFP, September 18, 2011]

In the biography, Abdullah praises Raffles — who had employed him as a translator — but offered a less than complimentary description of British sailors who docked in his hometown Malacca, now part of Malaysia. "To see an Englishman was like seeing a tiger, because they were so mischievous and violent... At that time I never met an Englishman who had a white face, for all of them had 'mounted the green horse', that is to say, were drunk," he wrote. "So much so that when children cried their mothers would say, 'Be quiet, the drunken Englishman is coming,' and the children would be scared, and keep quiet."

the Tanglin Club was to Singapore what the Pegu Club was to Rangoon and what the Selangor Club was to Kuala Lumpur.

Singapore as a Crown Colony

After years of campaigning by a small minority of the British merchants, who had chafed under the rule of the Calcutta government, the Straits Settlements became a crown colony on April 1, 1867. Under the crown colony administration, the governor ruled with the assistance of executive and legislative councils. The Executive Council included the governor, the senior military official in the Straits Settlements, and six other senior officials. The Legislative Council included the members of the Executive Council, the chief justice, and four nonofficial members nominated by the governor. The numbers of nonofficial members and Asian council members gradually increased through the years. Singapore dominated the Legislative Council, to the annoyance of Malacca and Penang. [Source: Library of Congress *]

By the 1870s, Singapore businessmen had considerable interest in the rubber, tin, gambier, and other products and resources of the Malay Peninsula. Conditions in the peninsula were highly unstable, however, marked by fighting between immigrants and traditional Malay authorities and rivalry among various Chinese secret societies. Singapore served as an entrepôt for the resources of the Malay Peninsula and, at the same time, the port of debarkation for thousands of immigrant Chinese, Indians, Indonesians, and Malays bound for the tin mines and rubber plantations to the north. Some 250,000 Chinese alone disembarked in Singapore in 1912, most of them on their way to the Malay states or to the Dutch East Indies. *

A number of events beginning in the late nineteenth century strengthened Singapore's position as a major port and industrial center. When the Suez Canal opened, the Strait of Malacca became the preferred route to East Asia. Steamships began replacing sailing ships, necessitating a chain of coaling stations, including Singapore. Most of the major European steamship companies had established offices in Singapore by the 1880s. The expansion of colonialism in Southeast Asia and the opening of Thailand to trade under King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) brought even more trade to Singapore.

The spread of British influence in Malaya increased the flow of rubber, tin, copra, and sugar through the island port, and Singapore moved into processing and light manufacturing, some of which was located on its offshore islands. To serve the growing American canning industry a tin smelter was built in 1890 on Pulau Brani (pulau means island). Rubber processing expanded rapidly in response to the demands of the young automobile industry. Oil storage facilities established on Pulau Bukum made it the supply center for the region by 1902. *

British Military in Singapore in the Late 1800s

By the mid-nineteenth century, London was recognized as the supreme naval power in the region, despite the fact that it deployed only about twenty-four warships to patrol an area extending east from Singapore as far as Hong Kong and west from Singapore as far as India. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987*]

Between 1867 and 1914, London contributed little to the establishment of permanent armed forces in Singapore. Units of the British Army's Fifth Light Infantry Regiment, which included infantry units brought from India, were stationed on the island. More often than not, however, these forces were deployed in the Malay states to protect British citizens there during periods of domestic violence.

In 1867 when the strategic value of Singapore influenced London's decision to make the Straits Settlements a crown colony, the local governments were required to pay 90 percent of their own defense expenditures. The issue of collecting taxes from the residents of Singapore for defense remained controversial until 1933, when the Colonial Office finally agreed that the city should not be required to pay more than 20 percent of its revenue for defense costs.*

Law Enforcement in Singapore in the Late 1800s

In 1843 the British recruited a small group of itinerant workers and single-handedly trained and organized them into an effective police force. By 1856 gang robberies no longer were a major problem, but the secret societies continued to control lucrative gambling, drug, and prostitution operations.[Source: Library of Congress]

From 1867 to 1942, the Straits Settlements had unified law enforcement and criminal justice systems. However, colonial authorities in Singapore continued to respect religious and cultural customs in the Chinese and Malay communities as long as local practices were peaceful and residents respected British authority. In 1868 Governor Sir Harry Ord established a circuit court, and its jurisdiction over criminal and civil matters gradually expanded in Singapore during the period up to World War II. Leaders of the Chinese community appreciated the cooperative nature of British government officials and helped to promote respect for the law. By the 1880s, government efforts to reduce the criminal elements of the Chinese secret societies had succeeded in making the city a safer place to live. Europeans and Indians dominated the police force. Colonial authorities rarely hired Chinese for police work for fear the secret societies would infiltrate the force. [Source: Library of Congress]

During the period that Singapore was a crown colony, militia groups trained by the British army occasionally assisted the police force in maintaining civil order and promoted citizen involvement in protecting the city from foreign invasion. Even before Singapore became a crown colony, concerned citizens in the European community had formed a citizens' militia. In 1854 about sixty European expatriates established the Volunteer Rifle Corps to protect citizens from violent riots. Although most riots occurred because of factional fighting between Chinese secret societies, some disturbances also disrupted the commercial activities of the city.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Singapore Tourism Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated February 2026