SINGAPORE DURING WORLD WAR II

Two days after Pearl Harbor was attacked, on December 8, 1941, Singapore was attacked by the Japanese aircrafts. The British defended Singapore with 85,000 troops. In February 1942, Japanese sent forces pouring south down the Malay Peninsula. After the swift Japanese campaign in Malaya, Singapore was successfully attacked across the Johor Strait. Once described as an impregnable fortress, the British garrison at Singapore surrendered on February 15, 1942. Singapore remained occupied by the Japanese for the next three and half years, a time marked by oppression, hardship and loss of lives.

Most Singaporeans did not feel the effects of World War II until the first half of 1941. The main pressure on the Straits Settlements was the need to produce more rubber and tin for the Allied war effort. After the British surrendered the Japanese renamed Singapore island Syonan (“Light of the South”) and set about systematically dismantling the British establishment. Singapore suffered greatly during the war, first from the Japanese attack and then from Allied bombings of its harbor facilities. About 140, 000 allied troops were killed or imprisoned at the notorious Changi Prison.

The Japanese occupation of Singapore from 1942 to 1945 sparked a massive anti-Japanese movement in Singapore, especially among the Chinese population, who bore the brunt of the occupation in retaliation for their support of mainland China in its struggle against Japan. Thousands of Chinese were executed at Sentosa and Changi Beach; Malays and Indians were subject to systematic abuse. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

By the war’s end, the colony was in poor shape, with a high death rate, rampant crime and corruption, and severe infrastructure damage. During the 1942–45 occupation period, a favorable view of the colonial relationship had lapsed among the local population, as it had in other British colonies, and upon the return of the British, resulted in demands for self-rule.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SINGAPORE HISTORY: NAMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

JAPAN'S MALAYA CAMPAIGN AND DEFEAT OF THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE INVASION OF SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE AFTER WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

POLITICAL ACTIVITY IN PRE-INDEPENDENCE SINGAPORE: PAP, LEE KUAN YEW, COMMUNISTS, LABOUR FRONT factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE INDEPENDENCE: SELF RULE, UNION THEN SPLIT WITH MALAYSIA, CHALLENGES factsanddetails.com

LEE KUAN YEW — SINGAPORE'S FOUNDER-MENTOR — AND HIS LIFE, VIEWS AND DEATH factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE UNDER LEE KUAN YEW factsanddetails.com

Singapore and the British Prepare for War in the Late 1930s

In June 1937, Britain began to prepare for the possibility of war with Japan. Three British army battalions stationed in Singapore, one Indian battalion at Penang, and one Malay regiment at Port Dickson in the Malayan state of Negri Sembilan were the only regular forces available at the time for the defense of Singapore and the Malay Peninsula. Although the British military leaders had warned London in 1937 that the defense of Singapore was tied to the defense of Malaya and that any Japanese attack on the island would likely be made from the Malay Peninsula, their assessment was rejected by the British War Office, which was convinced that the impenetrable rain forests of the peninsula would discourage any landward invasion. Air bases were established in northern Malaya but were never adequately fortified. A new naval base was constructed on the northern coast of the island, but few ships were deployed there. Military strategists in London believed that the Singapore garrison could defend the island for about two months, or the time it would take for a relief naval force to arrive from Britain. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987*]

In December 1941, British and Commonwealth forces committed to the defense of the Malay Peninsula and Singapore comprised four army divisions supported by small numbers of aircraft and naval vessels that had been sent from other war zones to provide token support to the ground forces. Lieutenant General Arthur E. Percival, commander of these forces, deployed most units in the northern Malayan states of Kedah, Perak, Kelantan, and Terengganu. Fortified defensive positions were established to protect cities and the main roads leading south to Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, and Singapore. The British had no armor and very little artillery, however, and air bases that had been constructed in the Malayan states of Kelantan, Pahang, and Johore and in Singapore at Tengah, Sembawang, and Seletar were not well fortified. The attention of the War Office was focused on the fighting in Europe, and appeals to London for more aircraft went largely unanswered.*

A small fleet, comprising the aircraft carrier Unsinkable, the battleship Prince of Wales, the battle cruiser Repulse, and four destroyers, represented the only naval force deployed to Singapore before the outbreak of war in the Pacific. The Unsinkable ran aground in the West Indies enroute to Singapore, leaving the fleet without any air protection.*

Japanese Malaya Campaign

Japanese air and naval attacks on British and United States bases in Malaya and the Philippines were coordinated with the December 7, 1941, assault on the United States Pacific Fleet Headquarters at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Japan's Southern Army, headquartered in Saigon, quickly moved from bases in southern Indochina and Hainan to attack southern Thailand and northern Malaya on December 8 and the Philippines on December 10.

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese troops of two large convoys, which had sailed from bases in Hainan and southern Indochina, landed at Singora (now Songkhla) and Patani in southern Thailand and Kota Baharu in northern Malaya. One of Japan's top generals and some of its best trained and most experienced troops were assigned to the Malaya campaign. By the evening of December 8, 27,000 Japanese troops under the command of General Yamashita Tomoyuki had established a foothold on the peninsula and taken the British air base at Kota Baharu. Meanwhile, Japanese airplanes had begun bombing Singapore. Hoping to intercept any further landings by the Japanese fleet, the Prince of Wales and the Repulse headed north, unaware that all British airbases in northern Malaya were now in Japanese hands. Without air support, the British ships were easy targets for the Japanese air force, which sunk them both on December 10. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The main Japanese force moved quickly to the western side of the peninsula and began sweeping down the single north-south road. The Japanese divisions were equipped with about 18,000 bicycles. Whenever the invaders encountered resistance, they detoured through the forests on bicycles or took to the sea in collapsible boats to outflank the British troops, encircle them, and cut their supply lines. Penang fell on December 18, Kuala Lumpur on January 11, 1942, and Malacca on January 15. The Japanese occupied Johore Baharu on January 31, and the last of the British troops crossed to Singapore, blowing a fifty-meter gap in the causeway behind them. *

See Southeast Asia, World War II: JAPANESE INVASION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA IN WORLD WAR II: factsanddetails.com ; JAPAN DEFEATS THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II AND TAKES MALAYA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

Japanese Invasion of Singapore

The prediction that Japan would conquer the Malay Peninsula before attempting an invasion of Singapore proved to be correct. Lieutenant General Yamashita Tomoyuki was placed in command of the Twenty-fifth Army comprising three of the best Japanese divisions. The Japanese used tactics developed specifically for the operation in northern Malaya. Tanks were deployed in frontal assaults while light infantry forces bypassed British defenses using bicycles or boats, thereby interdicting British efforts to deliver badly needed reinforcements, ammunition, food, and medical supplies. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Cut off from their supply bases in southern Malaya and Singapore, demoralized by the effectiveness of Japan's jungle warfare, and with no possibility that additional ground or air units would arrive in time to turn the tide of battle, the British withdrew to Singapore and prepared for the final siege. The Japanese captured Penang on December 18, 1941, and Kuala Lumpur on January 11, 1942. The last British forces reached Singapore on January 27, 1942, and on the same day a 55-meter gap was blown in the causeway linking Singapore and Johore.

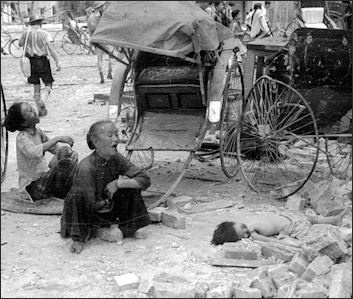

women and a dead child in Singapore

In January 1942, London had provided an additional infantry division and delivered the promised Hurricane fighter aircraft, although the latter arrived in crates and without the personnel to assemble them. In the battle for Singapore, the British had the larger ground force, with 70,000 Commonwealth forces in Singapore facing 30,000 Japanese. The Japanese controlled the air, however, and intense bombing of military and civilian targets hampered British efforts to establish defensive positions and created chaos in a city whose population had been swollen by more than a million refugees from the Malay Peninsula. Yamashita began the attack on February 8. Units of the Fifth and Eighteenth Japanese Divisions used collapsible boats to cross the Johore Strait, undetected by the British, to Singapore's northwest coast. By February 13, the Japanese controlled all of the island except the heavily populated southeastern sector. General Percival cabled Field Marshall Sir Archibald Wavell, British Supreme Commander in the Far East, informed him that the situation was hopeless, and received London's permission to surrender. On February 15, one week after the first Japanese troops had crossed the Johore Strait and landed in Singapore, Percival surrendered to Yamashita.*

See Separate Article:JAPANESE INVASION OF SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

Sinking of the Tanjong Penang

Describing the sinking of the Tanjong Penang, a refugee ship with 250 women and children hit by shells from a Japanese destroyer, in February 1942 one passenger wrote: "We settled down to sleep on the deck for the night, when suddenly a searchlight shone on us, and without any warning a shot was fired, and then another, both hitting the ship. When the shelling stopped...people were lying dead and wounded all around, but there was little we could do for the ship was sinking rapidly." [Source: “Eyewitness to History “, edited by John Carey, Avon Books, 1987]

"We both stepped into the water, and presently managed to pick up a small raft...During the night we picked up more people; on the end there sixteen of us holding on to two rafts — including six children, two being under one year old. We lost one or two the next morning; they just could not hold on."

"On the second day the children went mad, and we had a difficult time with them. We lost them all. That night I found myself alone with one other woman, so we got rid of our raft and just used the small one. We could see small islands in the distance, so next day we tried with our hands to paddle towards them, but the current was against us...I was picked up on the first evening” after that “by a Japanese cruiser."

Japanese Occupation of Singapore

The Japanese occupied Singapore from 1942 until 1945. They designated it the capital of Japan's southern region and renamed it Shonan, meaning "Light of the South" in Japanese. All European and Australian prisoners were interned at Changi on the eastern end of the island — the 2,300 civilians at the prison and the more than 15,000 military personnel at nearby Selarang barracks. The 600 Malay and 45,000 Indian troops were assembled by the Japanese and urged to transfer their allegiance to the emperor of Japan. Many refused and were executed, tortured, imprisoned, or sent as forced laborers to Thailand, Sumatra, or New Guinea. Under pressure, about 20,000 Indian troops joined the Japanese-sponsored Indian National Army to fight for India's independence from the British. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The Asian civilian population watched with shock as their colonial rulers and supposed protectors were marched off to prison and the Japanese set about establishing their administration and authority. The Chinese were to bear the brunt of the occupation, in retribution for support given by Singapore Chinese to China in its struggle against Japan. All Chinese males from ages eighteen to fifty were required to report to registration camps for screening. The Japanese or military police arrested those alleged to be antiJapanese , meaning those who were singled out by informers or who were teachers, journalists, intellectuals, or even former servants of the British. Some were imprisoned, but most were executed, and estimates of their number range from 5,000 to 25,000. Many of the leaders of Singapore's anti-Japanese movement had already escaped, however, and the remnants of Dalforce and other Chinese irregular units had fled to the peninsula, where they formed the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army. *

; JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA AND THE PACIFIC DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

Harsh Conditions During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore

The harsh treatment by the Japanese in the early days of the occupation undermined any later efforts to enlist the support of Singaporeans for the Japanese vision of a Greater East Asia CoProsperity Sphere, which was to comprise Japan, China, Manchuria, and Southeast Asia. Singapore's prominent Chinese leaders and businessmen were further disaffected when the Japanese military command bullied them into raising a S$10 million "gift" to the Japanese as a symbol of their cooperation and as reparation for their support for the government of China in its war against Japan. The Chinese and English schools were pressured to use Japanese as the medium of instruction. The Malay schools were allowed to use Malay, which was considered the indigenous language. The Japanesecontrolled schools concentrated on physical training and teaching Japanese patriotic songs and propaganda. Most parents kept their children at home, and total enrollment for all the schools was never more than 7,000. Although free Japanese language classes were given at night and bonuses and promotions awarded to those who learned the language, efforts to replace English and Chinese with Japanese were generally unsuccessful. [Source: Library of Congress *]

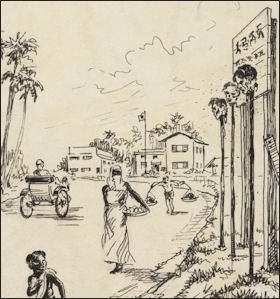

Chinese heads on poles in Singapore

Serious disruption of not only the economy but the whole fabric of society marked the occupation years in Singapore. Food and essential materials were in short supply since the entrepôt trade that Singapore depended on to provide most goods was severely curtailed by the war. Chinese businessmen collaborated with corrupt Japanese officials to establish a flourishing black market for most items, which were sold at outrageous prices. Inflation grew even more rampant as Japanese military scrip flooded the economy. Speculation, profiteering, bribery, and corruption were the order of the day, and lawlessness against the occupation government almost a point of honor. *

As the war wound down and Japanese fortunes began to fade, life grew even more difficult in Shonan. Military prisoners, who suffered increasing hardship from reduced rations and brutal treatment, were set to work constructing an airfield at Changi, which was completed in May 1945. Not only prisoners of war but also Singapore's unemployed civilians were impressed into work gangs for labor on the Burma-Siam railroad, from which many never returned. As conditions worsened and news of Japanese defeats filtered in, Singaporeans anxiously awaited what they feared would be a bloody and protracted fight to reoccupy the island. Although Japan formally surrendered to the Allies on August 15, 1945, it was not announced in the Singapore press until a week later. The Japanese military quietly retreated to an internment camp they had prepared at Jurong. On September 5, Commonwealth troops arrived aboard British warships, cheered by wildly enthusiastic Singaporeans, who lined the five-kilometer parade route. A week later, on the steps of the municipal building, the Japanese military command in Singapore surrendered to the supreme Allied commander in Southeast Asia, Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. *

Japanese Occupation and Brutality in Singapore

On the Japanese in Singapore, Lee wrote: "I passed a group of soldiers, I tried to look as inconspicuous as possible. But they were not to be denied. One soldier...beckoned to me. When I reached him, he thrust the bayonet on his rifle through the brim of my hat, knocking it off, slapped me roundly and motioned me to kneel. He then shoved his right boot against my chest and sent me sprawling on the road. As I got up, he motioned me to go back the way I had come. I had got off lightly. Many others who did not know the new rules of etiquette and did not bow to Japanese sentries at crossroads or bridges were made to kneel for hours in the sun, holding a heavy boulder over their heads until their arms gave way." Chinese looters who were caught were beheaded. Their heads were displayed at the local cinema as an example to others. [Source: “The Singapore Story” by Lee Kuan Yew, 1998, Times Editions]

Describing a Japanese search of his home, Lee wrote: "They roamed all over the house and compound. They looked for food, found the provisions my mother had stored, and consumed whatever they fancied, cooking in the compound over open fires. They made their wishes known with signs and guttural noises. When I was slow to understand what they wanted, I was cursed and frequently slapped.

In February 1942, Lee was ordered onto a truck by Japanese soldiers who were supposed to deliver him to a work site. He said he needed time to gather his things and the truck left without him. The people on the truck were never heard from again. "Somehow, I felt that particular lorry was not going to carry people to work," he said.

Lee wrote: "I discovered later that those picked out at random at the checkpoint were taken to the grounds of Victoria School...Their hands were tied behind their backs and they were transported to a beach at Tanah Meraj Besar...There they were forced to walk toward the sea. As they did, Japanese machine gunners massacred them. Later, to make sure they were dead, each corpse was kicked, bayoneted and abused in other ways. There was no attempt to bury the bodies, which decomposed as they were washed up and down the shore."

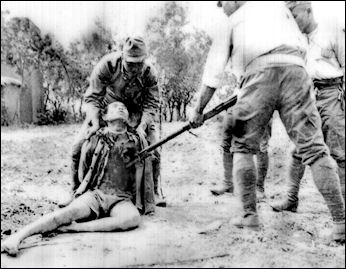

Sook Ching Massacre in February and March 1942

After Percival’s surrender ended the military campaign, the Japanese Army grew increasingly concerned about moral and financial support from Malayan and Singaporean Chinese for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government in China. In response, the Japanese launched an operation they termed Daikensho (“the Great Inspection”), known among the Chinese as Sook Ching (“the Purge,” a term coined in 1946). Yamashita authorized his forces to work with the Kempeitai to eliminate Chinese groups believed likely to undermine Japanese rule. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, ww2db.com ]

Those targeted included known supporters of the China Relief Fund, Chinese men bearing tattoos—suspected of belonging to secret societies—as well as communists and political activists. The operation soon widened far beyond these categories and came to encompass almost all Chinese men, many of whom had no connection to anti-Japanese activities. In Singapore, Chinese men were rounded up and taken to isolated locations such as Changi, Punggol, Blakang Mati, and Bedok, where they were executed by drowning or machine-gunning. In Penang, killings were equally indiscriminate, with entire Chinese villages detained and executed. The purge was halted on 3 March 1942.

Because records were poorly kept, the death toll has never been conclusively established. Postwar Japanese authorities acknowledged approximately 5,000 deaths, while Singaporean estimates ran as high as 100,000. Most historians, drawing on evidence presented during postwar trials, place the figure between 25,000 and 50,000.

The massacre destroyed any prospect of cooperation between the Japanese and the local population in Malaya and Singapore, Chinese and non-Chinese alike. As a result, large numbers of Japanese troops were tied down in both territories to maintain order. In 1947, seven Japanese officers were tried and convicted of war crimes related to the Sook Ching Massacre. Lieutenant Colonel Masayuki Oishi, commander of the No. 2 Field Kempeitai, was executed on 26 June 1947, as was Lieutenant General Saburo Kawamura. The remaining five officers received life sentences, including Lieutenant General Takuma Nishimura, who was later convicted by an Australian court for the Parit Sulong Massacre and executed under the Australian tribunal’s sentence.

Accounts of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore

Reporting on what it was like in Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew wrote, "From the end of 1943, food became scarcer and scarcer. Reduced to eating old, moldy, worm-eaten stock mixed with Malayan-grown rice, we had to find substitutes. My mother, like many others, stretched what little we could get...It was amazing how hungry my brothers and I became one hour after each meal...meanwhile, inflation had been increasing month by month, and by mid-1944 it was no longer possible to live on only salary . But there were better and easier pickings to be had as a broker on the black market." [Source: “The Singapore Story” by Lee Kuan Yew, 1998, Times Editions]

During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong the port facilities fell into disrepair, the governor was imprisoned in a luxury hotel, the British residents were imprisoned, torture cages were set up on the steps of the courthouse, trade virtually stopped and the Hong Kong and Shanghai bank was ordered to issue worthless currency. In Hong Kong, the Japanese did experiments with snakes and turned sumptuous mansions into geisha houses.

Romanus Miles wrote in the BBC People’s War: “We also discovered to our cost,that the infamous Kempeitai Division of the Nippon army now garrisoned our district. They were the vanguard of the successful assault on Singapore leading the 5th, 18th divisions and Imperial Guards. The men came from mining communities in northern Japan, were exceptionally tough and practiced their cruel brutality in occupied China. Now they were our masters setting up roadblocks all over the city terrifying anyone who dared to pass. This we had to do daily and I shall never forget the fear I had approaching one of these check points. Every bridge and major road junction became a terrifying experience for travelers. The soldiers manning these posts looked fearsome in their coarse uniforms, and those caps with the flaps. They took a delight in slapping or kicking us as we lined up to bow to the sentries. All watches and jewellery were taken, the owner usually receiving a slap as compensation and they liked British made bicycles especially the Raleigh make. Because of language and custom differences, misunderstandings often occurred with tragic consequences. [Source: BBC’s People’s War]

“For instance, the Japs pointed to their nose if they meant themselves just as we would point to our chest so if misunderstood tempers would flare up. When I pointed to my chest the sentry thought I had something on me and began to inspect me closely causing move havoc. Bowing the Japanese way was also a source of trouble so there was much shouting and violence. Often a few unfortunate souls would be bound tightly with rope and left in the hot sun, their fate unknown.

“We soon learnt the danger words like “Bageiroh, kurra and nanda” and would respond with much bowing. My heart would sink when having passed the post thinking all was well, I’d hear a loud “Oi’ and turning around I’d see a sergeant languishing in a chair in the shade beckoning me over. He was usually curious about my skin colour and if I didn’t satisfy his questions he would get nasty. On one occasion I was grabbed by my hair and had my head pulled down for inspection of my scalp. It was scary and just one of my many frightening experiences in those tyrannical times.

“Using our wits my Brother and I began claiming German or Italian nationality at interrogations and were rewarded with a pat on the head and a smile. But on one occasion it didn’t work, because the Jap was drunk and particularly nasty so in the end with a nod from L, we literally ran for our lives down the back streets of the Capitol cinema and got away with it. I can imagine what would have happened to us if we got caught. There were many proclamations from the army, displayed on notice boards in public places like markets, or just pasted onto street lamp post. Invariably they ended with a dire threat of sever punishment or death for non-compliance.

“All Eurasians had to assemble at the Padang near the Singapore cricket pavilion to be screened on a particular day. So with water bottles, food and sun hats we went there wondering if we would ever return. Jap guards ringed the area with machine guns, looking menacing but after being harangued in the hot sun by English speaking officers about co-operating with the new regime we were allowed to go home. There was a reminder that they were going to check birth certificates at a later date.

The date 1942 was now 2602, Singapore became known as Syonan-to, meaning “Light of the South” and the Emperor Hirohito was God. “Syonan- to” sounded to the local Hokkien Chinese like “Birdcage Island”, which was a sinister thought. Bowing to the North East, the bearing of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was a ritual we all got used to daily. At the road blocks, the sentries would ask locals in Malay where they were going, and if the response was Singapore, which was the customary term for the city a rain of blows would descend on the unwary individual until he remembered it was Syonan-to. On one occasion I watched a man beaten to the ground for replying “Raja” meaning King, when shown King George’s head on a coin.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Singapore Tourism Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated February 2026