JAPANESE INVASION OF SINGAPORE

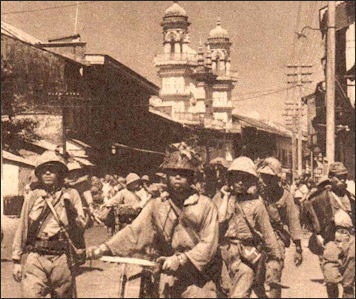

fighting in Malaysia

Singapore was the Japanese goal in Southeast Asia. On December 8, 1941, the day after the raid on Pearl Harbor, Japan invaded Malaya and began bombing Singapore. The Japanese overran the Malay peninsula in about eight weeks, advancing on bicycles across the Malay peninsula on excellent British-built roads while the British forces in Southeast Asia retreated to Singapore.

On December 8, Japanese troops of two large convoys, which had sailed from bases in Hainan and southern Indochina, landed at Singora (now Songkhla) and Patani in southern Thailand and Kota Baharu in northern Malaya. One of Japan's top generals and some of its best trained and most experienced troops were assigned to the Malaya campaign. By the evening of December 8, 27,000 Japanese troops under the command of General Yamashita Tomoyuki had established a foothold on the peninsula and taken the British air base at Kota Baharu. Meanwhile, Japanese airplanes had begun bombing Singapore. Hoping to intercept any further landings by the Japanese fleet, the Prince of Wales and the Repulse headed north, unaware that all British airbases in northern Malaya were now in Japanese hands. Without air support, the British ships were easy targets for the Japanese air force, which sunk them both on December 10. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The main Japanese force moved quickly to the western side of the peninsula and began sweeping down the single north-south road. The Japanese divisions were equipped with about 18,000 bicycles. Whenever the invaders encountered resistance, they detoured through the forests on bicycles or took to the sea in collapsible boats to outflank the British troops, encircle them, and cut their supply lines. Penang fell on December 18, Kuala Lumpur on January 11, 1942, and Malacca on January 15. The Japanese occupied Johore Baharu on January 31, and the last of the British troops crossed to Singapore, blowing a fifty-meter gap in the causeway behind them. *

RELATED ARTICLES:

SINGAPORE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

JAPAN'S MALAYA CAMPAIGN AND DEFEAT OF THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE DURING WORLD WAR II: POOR BRITISH DEFENSE, HARSH JAPANESE OCCUPATION factsanddetails.com

PEARL HARBOR, JAPANESE VICTORIES AND OCCUPATION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com;

BEGINNING OF WORLD WAR II IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC factsanddetails.com;

BRITISH IN MALAYSIA: TIN, RUBBER AND HOW THEY TOOK CONTROL factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE INVASION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com;

JAPAN TAKES THE PHILIPPINES: MACARTHUR, CORREGIDOR AND THE BATAAN DEATH MARCH factsanddetails.com;

JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA AND THE PACIFIC DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com INTERNED JAPANESE AMERICANS DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “World War II and Southeast Asia” by Gregg Huff Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: Volume 2, Part 2, From World War II to the Present” by Nicholas Tarling Amazon.com; “Malayan Campaign” by Hourly History and Matthew J. Chandler-Smith Amazon.com; “The Battle For Singapore: The true story of the greatest catastrophe of World War II” by Peter Thompson Amazon.com; “8 Miraculous Months in the Malayan Jungle: A WWII Pilot's True Story of Faith, Courage, and Survival” by Donald J. "DJ" Humphrey II Amazon.com; ”The Bridge Over the River Kwai” by Pierre Boulle, a classic novel that inspired the film Amazon.com; “The Second World War Asia and the Pacific Atlas (West Point Millitary History Series) by Thomas E. Griess Amazon.com; “The Pacific War, 1931-1945: A Critical Perspective on Japan's Role in World War II” by Saburo Ienaga Amazon.com; “Japan at War in the Pacific: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese Empire in Asia: 1868-1945" by Jonathan Clements Amazon.com

Singapore’s Military Defenses Before World War II

Malayan Campaign

The Singapore naval base was built and supplied to sustain a siege long enough to enable Britain's European-based fleet to reach the area. By 1940, however, it was clear that the British fleet and armed forces were fully committed in Europe and the Middle East and could not be spared to deal with a potential threat in Asia. In the first half of 1941, most Singaporeans were unaffected by the war on the other side of the world, as they had been in World War I. The main pressure on the Straits Settlements was the need to produce more rubber and tin for the Allied war effort. Both the colonial government and British military command were for the most part convinced of Singapore's impregnability. *

Even by late autumn 1941, most Singaporeans and their leaders remained confident that their island fortress could withstand an attack, which they assumed would come from the south and from the sea. Heavy fifteen-inch guns defended the port and the city, and machine-gun bunkers lined the southern coast. The only local defense forces were the four battalions of Straits Settlements Volunteer Corps and a small civil defense organization with units trained as air raid wardens, fire fighters, medical personnel, and debris removers. Singapore's Asians were not, by and large, recruited into these organizations, mainly because the colonial government doubted their loyalty and capability. The government also went to great lengths to maintain public calm by making highly optimistic pronouncements and heavily censoring the Singapore newspapers for negative or alarming news. Journalists' reports to the outside world were also carefully censored, and, in late 1941, reports to the British cabinet from colonial officials were still unrealistically optimistic. If Singaporeans were uneasy, they were reassured by the arrival at the naval base of the battleship Prince of Wales, the battle and four destroyers cruiser Repulse, on December 2. The fast and modern Prince of Wales was the pride of the British navy, and the Repulse was a veteran cruiser. Their accompanying aircraft carrier had run aground en route, however, leaving the warships without benefit of air cover. *

The British had begun building a naval base at Singapore in 1923, partly in response to Japan's increasing naval power. A costly and unpopular project, construction of the base proceeded slowly until the early 1930s when Japan began moving into Manchuria and northern China. A major component of the base was completed in March 1938, when the King George VI Graving Dock was opened; more than 300 meters in length, it was the largest dry dock in the world at the time. The base, completed in 1941 and defended by artillery, searchlights, and the newly built nearby Tengah Airfield, caused Singapore to be ballyhooed in the press as the "Gibralter of the East." The floating dock, 275 meters long, was the third largest in the world and could hold 60,000 workers. The base also contained dry docks, giant cranes, machine shops; and underground storage for water, fuel, and ammunition. A self-contained town on the base was built to house 12,000 Asian workers, with cinemas, hospitals, churches, and seventeen soccer fields. Above-ground tanks held enough fuel for the entire British navy for six months. The only thing the giant naval fortress lacked was ships. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Battle of Singapore in Early February 1942

On 1 February 1942, Japanese forces reached Singapore Island after overrunning British, Australian, and Indian troops. By 5 February, reduced to just 18 tanks and short of ammunition and food, the smaller force commanded by Yamashita launched an attack on Pulau Ubin in the east. This move was a bluff, intended to suggest that a major Japanese assault was coming from the east. The ruse deceived Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, who shifted his main ammunition reserves eastward. When the real Japanese assault came from the northwest, Singapore’s defenses were critically misaligned. On 8 February, the invasion of Singapore began with landings on the island’s northwest coast. Australian troops initially repelled the landings and inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese. However, amid the confusion of battle, the Australians withdrew unnecessarily, allowing Japanese troops to secure key shore defense positions. Subsequent Japanese landings met little resistance. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, ww2db.com ]

From the outset, British commander Percival ordered the destruction of docks and fuel depots to deny their use to the enemy. While this did deprive Japan of readily available infrastructure and supplies, it also had a corrosive effect on morale among the defenders. The early demolition of these facilities fostered a sense of inevitability and defeat. “Such moves instilled the soldiers with the notion that the battle had already been lost.”

On 10 February, the Japanese 5th and 18th Divisions overwhelmed the 22nd Australian Brigade, which withdrew deeper into the city and, in the chaos, turned on civilians, looting food and liquor. By this stage, Japanese tanks had entered Singapore in strength, first scattering Indian units at the hills of Bukit Timah and then blunting a counterattack led by British Brigadier Coates. Although RAF fighter pilots initially shot down several Japanese bombers, most were soon eliminated in dogfights against the superior Zero fighters. Civilians continued to flee the city as they had earlier, but many evacuation boats were now strafed by Japanese aircraft. On 13 February, Japanese forces seized or damaged most of the city’s reservoirs in an effort to sow panic by cutting off the water supply. “While there’s water,” Lieutenant General Arthur Percival declared, “We fight on.”

By 14 February, Japanese troops had pushed into the city itself, and atrocities followed. Lieutenant Western, a British medical officer, attempted to surrender under a white flag but was bayoneted to death. Japanese troops then entered Alexandra Hospital, killing more than 300 doctors, nurses, and patients, most with bayonets. When Yamashita learned of the incident, he ordered the soldiers responsible to be executed at the hospital.

Other atrocity reports described even more gruesome acts, including accounts of captured British soldiers being mutilated and displayed in trees for Allied patrols to discover, with placards hung around their necks reading “he took a long time to die.” These acts were intended to, and to some extent succeeded in, demoralizing Allied troops.

At 1400 hours on Sunday, 15 February, Percival concluded that his forces had supplies for only two more days of fighting and chose to surrender. Yamashita asked Percival, who was dressed in the baggy tropical shorts of the British uniform of the day, “do you wish to surrender unconditionally?” Percival replied, “Yes we do,” sealing the fate of the so-called “Impregnable Fortress” of Singapore at the hands of General Tomoyuki Yamashita. In reality, Yamashita’s own forces had ammunition for only a few more days, but Percival was unaware of this. Singapore—the Gibraltar of the East—would remain under Japanese control until the end of the war. Even in the final hours, the British coastal batteries of 15-inch and 19-inch guns remained trained southward, awaiting a naval assault that never came.

Lee Kuan Yew's Account of the Invasion of the Malay Peninsula and Singapore

The Japanese began attacking Singapore with planes before dawn, just hours after the Pearl Harbor attack. Lee Kuan Yew, the future leader of Singapore, wrote in Newsweek: "I was awakened by the dull thud of exploding bombs. The war with Japan had begun. It was a complete surprise. The street lights had been on, and the air raid sirens did not sound until those Japanese planes dropped their bombs, killing 60 people and wounding 130...Nearly everyone believed Singapore would be the main target for an attack, and it would therefore be prudent to return to the countryside of Malaya, which offered more safety from Japanese bombers."[Source: “The Singapore Story” by Lee Kuan Yew, 1998, Times Editions]

Later, Lee wrote In Newsweek, "Stories came down from Malaya of the rout on the war front, the ease with which the Japanese were cutting through British lines and cycling through rubber estates down the peninsula, landing behind enemy lines on boats and sampans, forcing more retreats. By January the Japanese forces were ensnaring Johor, and their planes started to bomb Singapore in earnest, day and night. I picked up my first casualties one afternoon...A bomb had fallen near the police station and there were several victims. It was a frightening sight."

Burning rubber plantation

“The British had thought Singapore was impregnable. They expected the Japanese to arrive by sea and built a line of guns facing the sea in Maginot Line fashion, and were unprepared for an overland attack from Malaya. The Japanese crossed into Singapore on a causeway which the British didn't blow up. "The Royal Engineers blew open a gap in the Causeway on the Johor side. But that didn’t delay the Japanese for long. The British engineers also blew up the pipeline that carried water from Malaysia to the island of Singapore.

Fighting in Singapore During Japanese Malaya Campaign

Singapore faced Japanese air raids almost daily in the latter half of January 1942. Fleeing refugees from the peninsula had doubled the 550,000 population of the beleaguered city. More British and Commonwealth of nations fleets and armed foces were brought to Singapore during January, but most were poorly trained raw recruits from Australia and India and inexperienced British troops diverted from the war in the Middle East. Singapore's Chinese population, which had heard rumors of the treatment of the Malayan Chinese by the invading Japanese, flocked to volunteer to help repel the impending invasion. Brought together by the common enemy, Guomindang and communist groups banded together to volunteer their services to Governor Shenton Thomas. The governor authorized the formation of the Chung Kuo Council (China National Council), headed by Tan Kah Kee, under which thousands volunteered to construct defense works and to perform other essential services. The colonial government also reluctantly agreed to the formation of a Singapore Chinese Anti-Japanese Volunteer Battalion, known as Dalforce for its commander, Lieutenant Colonel John Dalley of the Federated Malay States police force. Dalley put his volunteers through a ten-day crash training course and armed them with basic weapons, including shotguns, knives, and grenades. [Source: Library of Congress *]

From January 1-8, 1942, the two armies faced each other across the Johore Strait. The Japanese stepped up their air raids, bombing the airfields, naval base, and harbor area. Bombs also fell in the commercial and residential sections of the city, causing great destruction and killing and wounding many civilians. With their mastery of the skies, the Japanese could choose the time and place for invasion and maintain an element of surprise. Yamashita, however, had only 30,000 troops and limited ammunition available to launch against a British force of about 70,000 armed personnel. As the General Officer Commanding Malaya, Lieutenant General Arthur E. Percival commanded the defense of Singapore under the direction of General Archibald Wavell, the newly appointed commander in chief Far East, who was headquartered in Java. Percival's orders from British prime minister Winston Churchill through Wavell called for defending the city to the death, while executing a scorched-earth policy: "No surrender can be contemplated . . . . every inch of ground . . . defended, every scrap of material or defences . . . blown to pieces to prevent capture by the enemy . . . ." Accordingly, the troops set about the task of destroying the naval base, now useless without ships, and building defense works along the northern coast, which lay totally unprotected. *

On the night of February 8, using collapsible boats, the Japanese landed under cover of darkness on the northwest coast of Singapore. By dawn, despite determined fighting by Australian troops, they had two divisions with their artillery established on the island. By the next day the Japanese had seized Tengah Airfield and gained control of the causeway, which they repaired in four days. The British forces were plagued by poor communication and coordination, and, despite strong resistance by Commonwealth troops aided by Dalforce and other Chinese irregulars, the Japanese took Bukit Timah — the highest point on the island — on February 11. The British forces fell back to a final perimeter around the city, stretching from Pasir Panjang to Kallang, as Yamashita issued an invitation to the British to surrender. On February 13, the Japanese broke through the final perimeter at Pasir Panjang, putting the whole city within range of their artillery. As many as 2,000 civilians were killed daily as the Japanese continued to bomb the city by day and shell it at night.

Capture of Singapore

Japanese troops in Singapore

On February 2, 1942, the Japanese entered Singapore, easily driving out the British and capturing the naval base there on February 15. It was Britain's largest defeat ever. The capture of Singapore exposed the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) and the Indian Ocean to a Japanese advance. When Hitler heard the news he said, “Yes, a relief, an immense relief. But it was a turning point in history. It means the loss of a whole continent, and one might regret it, for it’s the white race which is the loser.”

Describing the first Japanese soldiers he encountered, Lee wrote in Newsweek, "They were outlandish figures, small, squat men carrying long rifles with bayonets. They exuded an awful stink, a smell I will never forget. It was the odor from the great unwashed after two months of fighting along jungle tracks and estate roads from Kota Bahru to Singapore." [Source: "The Singapore Story" by Lee Kuan Yew, 1998, Times Editions]

On the looting he witnessed in Singapore, Lee wrote: "I saw Malays carrying furniture and other items out of bigger houses...The Chinese looters went for goods in warehouses, less bulky and more valuable. The Japanese conquerors also went for loot. In the first few days, anyone in the street with a fountain pen or wristwatch was relived of it. Soldiers would go into houses either officially to search, or pretending to do so...appropriating any small items they could keep on their person."

Surrender of Singapore

The British in Singapore surrendered on February 15, an event Winston Churchill described as “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history.” Some 130,000 British, Australian and Indian troops were captured. Many Allied soldiers were imprisoned in the infamous Changri Gaol, and then transferred from there to work on the infamous Burma-Thai Death Railway and the Bridge over the River Kwai as prisoners of war. Describing the movement of British, Australian and Indian forces, Lee wrote, "The march started on 17 February 1942, and for two days and one night they tramped past the house and over the red bridge on their way to Changi. I sat on my veranda for hours at a time watching those men, my heart heavy as lead. Many looked dejected and despondent, perplexed that they had been beaten so decisively and easily. The surrendered army was a mournful sight."

Governor Thomas cabled London that "there are now one million people within radius of three miles. Many dead lying in the streets and burial impossible. We are faced with total deprivation of water, which must result in pestilence...." On February 13, Percival cabled Wavell for permission to surrender, hoping to avoid the destruction and carnage that would result from a house-to-house defense of the city. Churchill relented and on February 14 gave permission to surrender. On the evening of February 15, at the Japanese headquarters at the Ford factory in Bukit Timah, Yamashita accepted Percival's unconditional surrender. [Source: Library of Congress]

Allied troops surrender in Singapore

David Lamb wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “After a week of fierce fighting and mounting Allied and civilian casualties, Lt. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, his open-neck shirt dripping with medals, his boots kicked off under the negotiating table, and Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival, wearing shorts and a mustache, faced each other in the downtown Ford Motor Company factory. Yamashita pounded on the table with his fists for emphasis. "All I want to know is, are our terms acceptable or not? Do you or do you not surrender unconditionally? Yes or no?" the Japanese commander demanded. Percival, head bowed, answered softly, "Yes," and unscrewed his fountain pen. It was the largest surrender in British military history. The myth that British colonial powers were invincible and that Europeans were inherently superior to Asians was shattered. Japan renamed Singapore Syonan-to, Light of the South Island. The sun was setting on the British Empire. [Source: David Lamb, Smithsonian magazine, September 2007]

C. Peter Chen wrote in World War II Database: “At the conclusion of the Japanese campaign at Malaya, all Allied troops at the peninsula, numbered at over 138,000, were killed or captured. Many of the captured would endure a four-year long brutal captivity as forced labor in Indo-China. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill considered the British defeat at Singapore one of the most humiliating British defeats of all time. Many historians suggested similarly. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, ww2db.com]

Surrender of Singapore from the View of a British Soldier

Len (Snowie) Baynes wrote in the BBC’s People’s War: “At a quarter to three, I received what I hope will remain as the greatest shock of my life, as a messenger came with the order to lay our weapons down in front of us and surrender. I find it quite impossible to describe my feelings. Until now we had felt that we were holding our own, and anticipated pushing the Japanese back off the island before many more days had passed (we were still optimistically awaiting the arrival of Allied aircraft). [Source: BBC’s People’s War website ]

“Our wildest guesses did not take into account the possibility of abandoning the territory to the enemy - we had been told that the island must be retained at all costs, since it was an essential link in our communications with Australasia. In any case we did not think of throwing in the sponge while any of us remained alive - that was not the British way. I crept round the position passing on the order, adding the instruction to remove the rifle bolts and bury or otherwise hide them.

“Private Tanner stood 6ft 2in, and had proved himself in the fighting to be a very brave soldier - when he heard the order, he stood there unashamedly with tears streaming down his cheeks. His were not the only tears that sad day. I felt as though my bowels had been painlessly removed, my mind refused to work properly, and I was unable to grapple with the situation. Hardly a word was exchanged between us, as we awaited further orders. Talking about this afterwards, we agreed that we were still undergoing a feeling of bitter shame, with our arms lying useless on the ground and our country's enemy only a hundred yards away.

Events on the remainder of the island had been going very badly however, and we were one of the few regiments not to have been forced to withdraw from its allotted area. Singapore had no previously prepared positions for defence against an attack from the mainland of Malaya, and the story of the big unmanageable guns pointing out to sea is now familiar. For the previous few years, our military people had taught us the necessity for all-round defence in modern warfare, yet Singapore's only big guns were still concreted in to positions facing out to sea. Their main defensive weapons were therefore hardly used. This was at a time when nearly every army in the world was training paratroops, and our potential enemy had been advancing through the Chinese mainland for years. A few thousand pounds worth of concrete pill-boxes, strategically placed, a few mobile guns or tanks, and Singapore could well have proved, like Gibraltar, an impregnable fortress.

C. Peter Chen wrote in World War II Database: “At the conclusion of the Japanese campaign at Malaya, all Allied troops at the peninsula, numbered at over 138,000, were killed or captured. Many of the captured would endure a four-year long brutal captivity as forced labor in Indo-China. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill considered the British defeat at Singapore one of the most humiliating British defeats of all time. Many historians suggested similarly. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, ww2db.com]

“No plans seemed to have been worked out for the deployment of troops, however, should the Japanese do the obvious and attack from the dry land, instead of sailing into the muzzles of our big guns from seaward. At the time of surrender, as we were to learn later, the enemy had penetrated nearly everywhere, and Singapore City was full of leaderless men making for the docks in the hope of getting away on a ship from this doomed place. We were also told later that the order for surrender was given because the Japanese had cut off Singapore’s only water supply, which came from the mainland, and that we were giving in for the sake of the civilian population. Oriental people fully understand what face-saving is all about, and in the weeks that followed, they showed no gratitude to us for laying down our arms for their sakes. The Malays spat on the ground when they saw us during the first days after our surrender - but they were soon to learn that there are worse masters than the British.

Escape from Singapore Under a Hail of Bullets

Len (Snowie) Baynes wrote in the BBC’s People’s War: “We seemed to wait in our trenches after the arrival of the cease-fire order for a very long time, without anything happening. An hour and a half after we received it, men dug in fifty yards away, in the centre of a lawn, decided to climb out of their trenches - a machine gun opened fire on them, and they all lay still around their position. I ran back to our RAP to try to borrow a Red Cross flag to take out over the lawn, and fetch in any wounded. [Source: BBC’s People’s War]

“Dodging a hail of bullets from that same machine gun, I found our Medical Officer and explained my mission, but was told that since some of our men had fired on Japanese stretcher bearers, they had ceased to respect the Red Cross, and were firing indiscriminately at both stretcher bearers and ambulances. I was told to stay quietly with my men until further instructions were received. Again, it was later that we learned that Indian troops had fired on the Japanese from the windows of Robert’s Hospital, and this was responsible for the retribution.

“Stepping out through the front door of the house where the RAP was situated, and seeing an ambulance standing there, I looked in over the tailboard. Within seconds I came under machine gun fire from an unexpected direction, and tracer bullets whizzed past me like fireworks and into the ambulance. Although it seemed that I could have touched these bullets, again they all missed me. I jumped to cover into an alcove built in the wall of the house, and as I did so the ambulance burst into flames - a tracer bullet had penetrated the petrol tank. The fire spread and the ambulance became an inferno. The firing did not ease up, and I began to feel the intense heat. Soon I had to choose between roasting and stepping out again into the line of fire.

“The house was built on a slope, and like most of the dwellings in that area it was built on piers, high off the ground. I leapt out of the alcove and fell flat on the ground in a spot where I could roll back under the house, and managed to accomplish this in one movement. I lay there for a few seconds, getting my breath back, and watching the tracers fly past, almost within reach of my hand. Then the heat increased, and I realised that the fire had spread to the house, so crawled to the rear of the under-floor space.

“Teams of men were carrying the wounded to safety out of the back door, and they were not being fired on. I met Captain Coppin at the rear of BHQ, and stopped for a second to speak to him before carrying on behind the house. A steep bank arose a few yards from us, and I thought we were safe from fire for the moment. I continued on my way, but half-way along, two Japanese armed with a light machine gun suddenly appeared from behind a hedge, only four yards away. One yelled something that sounded like “shoot”, and the other released a burst of fire at me from point blank range.

“Before I could move, I felt a pain in the back of my neck, then dived under the building and rolled out of range. I put my hand up to my neck - no blood, I had been hit only by chips of brick from the wall. Captain Coppin had quite a shock when we came face to face later on. He had watched my progress from the corner, and seeing what had occurred, had reported my death to HQ.

“It later transpired that the Japanese had brought up their veteran troops. As we had defended our ground so well, they thought we were a crack regiment under the direct command of General Wavell. These enemy companies acted more or less independently, and had few lines of communication. Their leaders had therefore not been able to inform them of the cease-fire, and as a result this was our worst period, as, without weapons, we were picked off one by one.

I continued unscathed, however. Had I seen myself in a Western, being missed so many times at point blank range, I would probably have classed it as impossible fiction. Once again I reached my men unharmed, and as we awaited the next move our thoughts dwelt on what we had heard of the way the Japanese dealt with prisoners.

We had been told of soldiers' bodies found with their hands tied together with barbed wire and riddled with bullets, and that they liked torturing their captives before disposing of them. We knew that the Chinese, whom they had been fighting for several years, did treat their prisoners this way. Our comrades out on the lawn had been shot down in cold blood. We did not discuss these things as we waited in silence, each kept his thoughts to himself.

Image Sources: YouTube, National Archives of the United States; Wikimedia Commons; Gensuikan;

Text Sources: National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Yomiuri Shimbun, The New Yorker, Lonely Planet Guides, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, “Eyewitness to History “, edited by John Carey ( Avon Books, 1987), Compton’s Encyclopedia, “History of Warfare “ by John Keegan, Vintage Books, Eyewitness to History.com, “The Good War An Oral History of World War II” by Studs Terkel, Hamish Hamilton, 1985, BBC’s People’s War website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026