ETHNIC GROUPS IN MYANMAR

Paduang girl

Myanmar is one of the most ethnically diverse countries country in the world. Depending on how these groups are counted there are between 60 and 135 different groups. The latter figure (which is twice the number of ethnic groups in China) is arrived at by counting groups like Black Miao, Red Karen, White Karen, Burmese Karen and Mon Karen as four distinct groups, while ethnologists who use the 60 group count them as one. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: East and Southeast Asia”, edited by Paul Hockings (C.K. Hall & Company]

Myanmar’s non-Burman ethnic groups dominate the mountainous regions that surround the flood plains where most of the majority-Burman population live. Many of Myanmar’s states are named after the people that live there.

Describing a highland market Andrew Marshall wrote in “The Trouser People — In the Shadow of the Empire”: “At every corner I was bowled over by the sight of a woman in magnificent tribal finery. A ruddy-faced Lisu woman browsed at a cosmetics stall in an embroidered blue smock and maroon legging with delicate peppermint-green hems, a prig of herbs threaded deftly through her earlobe for safekeeping. There was an Akha woman with a stunning triangular headdress projected from the noon sun by a black wimple and festooned with coins and baubles, and a Silver Palaung woman wearing a cummerbund of beaten silver and black-rattan hoops stacked around her buttocks. In marked contrast, I spotted a dark-skinned woman wearing nothing but a skimpy sarong. I...realized later that Shan women in nearby village still around “as Scott said of the Wa’all unabashed, unhaberdashed, unheeding.”

U.S. Campaign for Burma, an exile group in close contact with Myanmar's ethnic leaders. Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), an exile media organisation,

MINORITIES IN MYANMAR factsanddetails.com;

INTHA LEG ROWERS AND THE FLOATING FARMS OF INLE LAKE factsanddetails.com;

CHIN PEOPLE: HISTORY, CHRISTIANITY, TATTOOS AND LIFE factsanddetails.com;

KACHIN MINORITY AND THEIR HISTORY AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com;

KACHIN LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com;

ROHINGYA AND THE PERSECUTION AND SUFFERING THEY ENDURE IN MYANMAR factsanddetails.com;

SHAN MINORITY: THEIR HISTORY, RELIGION AND OTHER PEOPLE IN SHAN STATE factsanddetails.com;

SHAN LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com;

PALAUNG PEOPLE: THEIR HISTORY, RELIGION AND LIFE factsanddetails.com;

NAGAS: THEIR HISTORY, LIFE AND CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com;

MOKEN SEA NOMADS: HISTORY, LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com;

MOKEN IN THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com;

MON PEOPLE factsanddetails.com;

HILL TRIBES FROM THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE factsanddetails.com;

MINORITIES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AND SOUTH CHINA: HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com;

LIFE AND CULTURE OF TRIBAL GROUPS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AND SOUTH CHINA factsanddetails.com;

HILL TRIBE ECONOMY, AGRICULTURE AND GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com;

AKHA MINORITY factsanddetails.com;

KAREN MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION, KAYAH AND GROUPS factsanddetails.com;

KAREN LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com;

PADAUNG LONG NECK WOMEN factsanddetails.com;

LAHU MINORITY factsanddetails.com;

LAHU PEOPLE LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com;

WA MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com;

WA PEOPLE LIFE AND SOCIETY factsanddetails.com;

WA STATE AND THE UNITED WA STATE ARMY factsanddetails.com;

LISU MINORITY: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com;

YAO (MIEN) MINORITY: GROUPS, BRANCHES AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com;

GOLDEN TRIANGLE: OPIUM, HEROIN, KUOMINTANG, HILL TRIBES AND THE CIA factsanddetails.com;

ILLEGAL DRUGS AND MYANMAR factsanddetails.com;

OPIUM AND HEROIN IN MYANMAR factsanddetails.com;

METHAMPHETAMINES, MYANMAR AND SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com;

KHUN SA: HIS LIFE, ARMY, AND THE OPIUM AND HEROIN TRADE factsanddetails.com

GOLDEN TRIANGLE DRUG LORDS: KHUN SA, LO HSING HAN, AND MISS HAIRY LEGS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Ethnofederalism and the Accommodation of Ethnic Minorities in Burma: United They Stand” by Naval Postgraduate School Amazon.com; “Political Authority in Burma's Ethnic Minority States: Devolution, Occupation, and Coexistence” by Mary P. Callahan Amazon.com; “Winning by Process: The State and Neutralization of Ethnic Minorities in Myanmar” by Jacques Bertrand, Alexandre Pelletier, et a Amazon.com; “Frontier Ethnic Minorities and the Making of the Modern Union of Myanmar: The Origin of State-Building and Ethnonationalism” by Zhu Xianghu Amazon.com; “Stalemate: Autonomy and Insurgency on the China-Myanmar Border” by Andrew Ong Amazon.com; “Rebel Politics: A Political Sociology of Armed Struggle in Myanmar's Borderlands” by David Brenner Amazon.com;“By Force of Arms: Armed Ethnic Groups in Burma” by Paul Keenan Amazon.com

Minority Group Numbers in Myanmar

Ethnic minorities make up about 30 to 40 percent of the Myanmar’s 55 million to 60 million people. It is difficult to calculate the minority numbers in Myanmar. The government has not done any known censuses or estimates for some time and if they have they haven’t released any information about them. There are about 15 million Karen, Shan, Kachin, in the mountainous region that Burma shares with China and Thailand. In this part of Myanmar there are no large roads or cities, only footpaths and villages.

The present population is generally estimated to be approximately 55 million, though no reliable census data exists, While the military junta presently ruling Burma claims that 67 to 70 percent of the population is ethnically Burman, this is based on skewed data from an old census in which anyone with a Burmese-language name was listed as Burman. By contrast, non-Burman groups set the figure at 70 percent non-Burman and 30 percent Burman. Other estimates range between these two extremes. [Source: Human Rights Watch, Sold to Be Soldiers, October 31, 2007]

While the Muslim and Christian communities are believed to be a very small minority nationally, the U.S. Department of State reported in 2005 that the size of Myanmar’s non-Buddhist population may be grossly underestimated. “According to the report, the country’s non-Buddhist population may be as high as 20 percent of the total population, rather than the 7 percent reported by the government.

Ethnic Diversity in Myanmar

Kachin

Linguists have identified 110 distinct ethnolinguistic groups, and the government recognizes 135 ethnic groups. The largest groups are the Shan (about four million), Karen (about three million), Arakanese or Rakhine (about two million), Chinese (over one million), Chin (over one million), Wa (about one million), Mon (about one million), Indians and Bengalis (about one million), Kachin (about less than one million), and Palaung (less than one million). With the exception of the Chinese, Indian, and Belgalis, each minority group occupies a relatively distinct area.[Source: Countries and Their Cultures everyculture.com ]

The Burmese have traditionally lives mainly in the river valleys and plains, particularly around the Irrawaddy River while the smaller ethnic minorities lived in the mountains and hills. Poor communicatiosn and transportation have tended to isolate ethnic groups from one another and form the lowland Burmese. Many highland people have never visited the lowlands and visa versa.

The Shan, Karens, Rashkine, Chin, Kayahs, Arakanese, Mons and Kachins all have their own semi-autonomous states. Many other minorities live in the Mon state. A third of the Karens live in the Karen state, two-thirds live elsewhere in Burma. There are very few foreigners in Myanmar and they are mostly Indians and Chinese.

According to Human Rights Watch: “Over the past three millennia various peoples have migrated into what is now Burma from other parts of East Asia, creating a diverse ethnic mix. The present population is generally estimated to be approximately 50 million, though no reliable census data exists; this is made up of Burmans and approximately 15 other major ethnicities, each of which has subgroups. While the military junta presently ruling Burma claims that 67 to 70 percent of the population is ethnically Burman, this is based on skewed data from an old census in which anyone with a Burmese-language name was listed as Burman. By contrast, non-Burman groups set the figure at 70 percent non-Burman and 30 percent Burman. Other estimates range between these two extremes. [Source: Human Rights Watch, Sold to Be Soldiers, October 31, 2007]

According to Countries and Their Cultures: “ The name Burma is associated with the dominant ethnic group, the Burmese... Efforts to create a broadly shared sense of national identity have been only partly successful because of the regime's lack of legitimacy and tendency to rely on coercion and threats to secure the allegiance of non-Burmese groups. The low level of education and poor communications infrastructure also limit the spread of a national culture. “Before colonial rule, Burma consisted essentially of the central lowland areas and a few conquered peoples, with highland peoples only nominally under Burmese control. The British brought most of the highlands peoples loosely under their control but allowed highland minorities to retain a good deal of their own identity. This situation changed after independence as the Burmese-dominated central government attempted to assert control over the highland peoples. Despite continued resistance to the central government, those in the lowland areas and the larger settlements in the highlands have come to share more of a common national culture. The spread of Burmese language usage is an important factor in this regard.”[Source: Countries and Their Cultures everyculture.com ++]

Different Ethnic Groups in Myanmar

Eight major ethnic groups—Arakanese, Burmese, Mon, Chin, Kachin, Karen, Karenni, and Shan—make up most of Myanmar’s population. Burmese are majority, comprising about 68 percent of the country population. The Burmese, Arakanese and Mon dress are closely related to one another and dress in a similar fashion while the Chin, Kachin, Karen, Karenni, and Shan are more distinct in clothes, culture and traditions.

Burmans (Bamars), who are related to Tibetans linguistically, make up two thirds of the population according to the Burman-dominated government. Minorities make up to 30 percent to 40 percent of the population. The Shan are the largest minority (9 percent). They live in northeast World War II. Other ethnic groups with sizable populations include the Karens (7 percent), who live in the east; the Rashkine (4 percent) who libe in the west: the Chin (2 percent), the Mon (2 percent), the Kachin (1.5 percent),and Chinese (1.4 percent). The remaining 5 percent or so of the population is made of minorities such as the Kayahs, Arakanese, Wa, Naga, Lahu, and Lisu.

The Shan, Karens, Rashkine, Chin, Kayahs, Arakanese, Mons and Kachins all have their own semi-autonomous states. Many of Myanmar’s vast natural resources are located in its ethnic nationality regions, particularly in Kachin State. Many mon-Mon minorities live in the Mon state. A third of the Karens live in the Karen state, two-thirds live elsewhere in Burma. There are very few foreigners in Myanmar and they are mostly Indians and Chinese.

Language Groups in Myanmar

Language Breakdown of Myanmar’s Minorities

The majority of the people speak Tibeto-Burman languages. Tibeto-Burman speakers in Burma can be divided into six distinct groups. The Burmish constitute the largest of these groups by population. Nungish speakers live in upland areas in Kachin State. The main Baric-speaking group is the Kachin (Jingpho) in Kachin State. The Kuki-Naga-speaking peoples include a large number of ethnic groups in the mountains along the border with India and Bangladesh. The Luish group includes the Kado, who live near the border with the Indian state of Manipur. The Karen groups live in the hills along the border with Thailand and the southern lowlands. The Lolo-speaking groups tend to be the most recent immigrants to Burma; they live in the highlands of Shan and Kachin states. [Source: Countries and Their Cultures everyculture.com ]

There are also large numbers of speakers of Austro-Tai languages. The largest Daic-speaking group is the Shan, who constitute the majority in Shan State. Smaller, related groups include the Tai Khun, Lue, Tai Nua, and Khamti. Other Austro-Tai speakers include the Austronesian-speaking Moken and small groups of Hmong and Mien in Shan State.

Early History of Minorities in Burma

Over the past three millennia various peoples have migrated into what is now Burma from other parts of East Asia, creating a diverse ethnic mix. Minorities in Burma arrived in three waves: 1) first the Mon and Khmer; 2) then Tibeto-Burman people; and 3) finally Tai-Chinese in the 13th and 14th centuries. There have been a lot of movment in recent centuries. Many of the ethnic groups in Thailand arrived in the last two centuries from Burma and China.

Enmities between certain ethnic groups go back hundreds of years, dating from the times that Burman, Mon-Khmer, and Rakhine kingdoms fought each other, while more peaceable peoples were driven into remote areas. The end result was a central plain dominated by Burmans, encircled by various non-Burman populations who form the majority in the outlying and more rugged regions of the country. Most of the ethnic groups are concentrated within a particular region, which has been a central factor in the formation of ethnicity-based armed groups, each based in their home region and drawing support from the local population. [Source: Human Rights Watch, Sold to Be Soldiers, October 31, 2007]

Under the pre-colonial Burman kingdoms as well as during British colonial rule, all of the main ethnic groups enjoyed a high degree of autonomy. The British colonists, the World War II Japanese occupying force and the present government have never completely controlled the mountainous regions in northern Burma and the kaleidoscope of ethnic groups that live there. Under the British the regions were simply known as the “Frontier Areas.” They generally stayed clear of these places and concentrated their energies on central “Ministerial Burma.”

During World War II many ethnic fighters were recruited by the British to fight against the Japanese. Many of these fighters would later fight against the Burmese government.

Up until recently about a third of the country wasn't even controlled by the Myanmar government. Along the mountainous northern and eastern border with China, Laos and Thailand ethnic insurgents and drug warlords established their own mini-states with their own hospitals and education systems.

Ethnolinguistic Map of Myanmar

History of Ethnic Minorities in Myanmar After World War II

After World War II, Aung San promised the possibility of a unified Burma to the country’s fractious tribes. He said, “We will have our differences, but, to take one example, if we are threatened with external aggression. We must fight back together." At negotiations held at Panglong in Shan State in 1947 he forged an agreement with the Shans, Chins, Kachins and other groups — but not the Karens. In return for joining the national state of Burma they would be granted a fair amount of autonomy within their own states. A constitution drawn up in 1949 gave the Shan and Karrenni the right to secede after several years.

The agreement forged at the Panglong Conference on February 12, 1947 today is celebrated as as 'Union Day' in Myanmar. But Aung San was assassinated in 1947 and none of those agreements was ever honored. Instead, the new Burmese government refused any autonomy to non-Burman ethnic regions. Facing a communist insurgency from the beginning, the government soon found itself also facing an increasing number of armed ethnicity-based resistance groups all over the country, most of which were seeking their own independence.

In the late and 1940s 1950s, internal struggles within the Burmese government was accompanied by struggles in the ethic states.. Exacerbating the problem was the conflict between the Kuomintang nationalists and the Communists in China. In 1949, the Communists defeated the Kuomintang and remnants of Chiang Kai-shek's defeated Kuomintang army retreated to the mountains of Burma along the Chinese border and tried to organize attacks against the Red Army from there. To raise money the Kuomintang encouraged peasant farmers to raise opium, which the Chinese nationalist sold for huge profits. This was the beginning of the Golden Triangle opium and heroin trade.

Forces made up of and aided by the Kuomintang became known as the White Flag Communists. They allied themselves with Shan fighters and fought some battles with Burmese government forces along the Chinese border.

Many of the peace treaties with minorities was based on a tacit agreement in which the government allowed the minorities to do anything they wanted, including producing and trafficking drugs, in return for not fighting against the government.

Before independence, Indians were a dominant presence in urban-centered commercial activities. With the outbreak of World War II, a large number of Indians left for India before the Japanese occupation. Through the 1950s, Indians continued to leave in the face of ethnic antagonism and antibusiness policies. The Indians remaining in Burma have been treated with suspicion but have avoided overt opposition to the regime.

Unrest Among Minorities After the Independence of Burma

Flag of KNLA

Unrest among ethnic minorities, mostly along the eastern border with Thailand and China, have plagued Burma since independence. Negotiations for independence after World War II brought suspicions among the political leaders of several ethnic minorities that their status would be undermined. Immediately after independence in 1948, serious divisions emerged between Burmese and non-Burmese political leaders, who favored a less unified state. After independence in 1948, the Burman armed forces of the new Burmese state entered the ethnic regions, militarised the government, and plundered the country’s natural resources, much of which is located in the minority regions. [Source: Min Zin, Foreign Policy, October 8, 2012]

Between 1948 and 1962, armed conflicts broke out between some of these minority groups and the central government. Although some groups signed peace accords with the central government in the late 1980s and early 1990s, others are still engaged in armed conflict. The Wa have signed a peace agreement but have retained a great deal of autonomy and control of much of the drug trade in northern Burma.

Military operations in ethnic minority areas and government policies of forced resettlement and forced labor have dislocated many ethnic groups, and have caused large numbers of refugees to flee to neighboring countries. At present there are around three hundred thousand refugees in Thailand, Bangladesh, and India, mostly from ethnic minorities.

Many of the ethnic wars in Myanmar have the roots in the breaching of the Panglong Agreement of 1947. Hannah Beech wrote in Time, “Suu Kyi’s father, Aung San, was one of the few Bamar to earn the trust of ethnic groups. He spearheaded the 1947 Panglong Conference, in which five ethnic groups, including the Kachin, agreed to join the Union of Burma in exchange for a certain amount of autonomy in a federalized system. Aung San, however, was assassinated soon after the Panglong agreement was signed, and civil war quickly descended over a nation that had only recently wrested itself from the British Empire. [Source: Hannah Beech, Time, January 28, 2013]

Policy Towards Minorities Under Myanmar’s Military Junta

In 1962 the head of the Burma army, General Ne Win, overthrew the civilian government and established the military rule that has continued to this day. He progressively stepped up the civil war against the dozen or more resistance and insurgent groups he was already facing, and his xenophobic economic policies and repression of the civilian population gradually dragged the country down into poverty.

In 1997 the military regime changed its name to the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), but this was not accompanied by any political liberalization. The state military or Tatmadaw, which had fewer than 200,000 men before 1988, announced a program to expand its strength to 500,000, and began much more intensive attacks throughout the country. This was facilitated by a mutiny in 1989 that caused the dissolution of the Communist Party of Burma, the country's largest opposition armed group. The SLORC was quick to approach the United Wa State Army, which had been formed from the remnants of the communist soldiers, and negotiated a ceasefire with it that still stands. Through the 1990s non-state armed groups found that they could no longer withstand the intensified attacks of the greatly expanded Burma army, and one by one the majority of them also entered into various forms of armistice agreements. These agreements do not address any political aspirations or human rights concerns of the non-state groups, but allow them to retain arms and partial control over small parts of their former areas. They are given freedom to conduct businesses including resource extraction and transportation services, and many of these groups have now become primarily money-making armies using their arms to protect their business interests and extort resources from local populations.

Some groups have continued to fight. Since 1995 the Burma army has been successful in capturing most of the former territories of these armies and in exploiting splits and factionalism within them, to the point where none of the remaining groups without ceasefires any longer controls significant territories and they primarily operate in small guerrilla units. These units harass local Burma army units but seldom leave their home areas. The main groups that are still fighting the Tatmadaw include the Shan State Army South (SSA-S), the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), and the Karenni Army (KA), none of which has more than 5,000 or 6,000 troops. Most of these groups gave up the objective of independence after 1988 and have instead been pursuing the objective of a democratic federal union. At present they are not a military threat to the SPDC's hold on power, but they continue to retain de facto control over some areas and defend some areas of refuge for displaced villagers.

Ethnic Political Parties in Myanmar

flag of the Shan State

Ethnic parties in Myanmar that particpated in the 2010 election included: 1) a new party formed by members of a ceasefire group (Mon National Democratic Front, MNDF) and a party that won seats in the 1990 elections (the New Mon State Party, NMSP); and 2) The Shan Nationalities League for Democracy, a Shan political party that came second in the 1990 election was participating in the election as the Shan Nationalities Democratic Party; 3) Lahu National Development Party (LNDP); 4) Kokang Democracy and Unity Party (KDUP); 5) Pa-Oh National Organisation (PNO); 6) Democratic Party (Burma) (DPM); ) Kayan National Party (KNP); 7) Rakhine State National Force of Myanmar (RSNF); ) Kayin People's Party (KPP); 8) Wa National Unity Party (WNUP); 9) Union of Karen/Kayin League (UKL); 10) Taaung (Palaung) National Party (TPNP); 11) Chin Progressive Party (CPP); 12) Rakhine Nationalities Development Party (RNDP); 13) Wa Democratic Party (WDP); 14) Unity and Democracy Party of Kachin State (UDPKS). +

Results for the Amyotha Hluttaw in the 2010 Elections. (Party, Seats, Net Gain/Loss, Seats percent, Votes percent, Votes, +/-): 1) Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), the junta-backed party: 129, 57.59; 2) Appointed: 56, +56, 25.00, -, -, +56; 3) Rakhine Nationalities Development Party (RNDP), an ethnic party: 7, 3.13, 263,678; 4) National Unity Party (NUP), a party linked with the military and former dictator Ne Win: 5, 2.23, 4,302,082; 5) National Democratic Force (NDF),formed by members of Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD: 4, 1.79, 1,488,543; 5) Chin Progressive Party (CPP), an ethnic party: 4, 1.79, 86,211; 6) All Mon Region Democracy Party (AMRDP), an ethnic party: 4, 1.79, 172,806; 7) Shan Nationalities Democratic Party (SNDP), an ethnic party: 3, 1.33, 496,039; 8) Phalon-Sawaw Democratic Party (PSDP): 3, 1.33, 77,825; 9) Chin National Party (CNP): 2, 0.89, 37,450; 10) Others, 7, 3.13. Total, 224, 100. +

Aung San Suu Kyi and Minorities

Hannah Beech wrote in Time: “Aung San Suu Kyi has disappointed some of Burma’s ethnic groups, including the Rohingya, a stateless Muslim people who now crowd refugee camps in Bangladesh. The Kachin too have long been wary that Suu Kyi’s democratic principles might not extend to their home in the Himalayan foothills. “She is a Nobel Peace Prize winner and she should stand up for victims of human-rights abuses in Kachin,” says Naw La, a Kachin activist and environmental campaigner who lives in Thailand. “If she doesn’t speak out for oppressed people, then who else will? I’m surprised and disappointed.” [Source: Hannah Beech, Time, January 28, 2013]

Back in 1947, in a historic agreement signed in the town of Panglong, Aung San Suu Kyi's father Aung San promised ethnic minorities a high level of autonomy in the future Union of Burma. But he was killed months later by a political rival, and subsequent governments failed to live up to Aung San's pledge. Since her latest release, Suu Kyi has called for a "second Panglong," a plea that had special resonance as fighting between ethnic Karen rebels and the Burmese military flared in January 2013 on the Thailand-Burma border. But once more, the limits of Suu Kyi's power come in to play: What leverage does she have to force the junta into meeting the demands of an array of disaffected rebel armies? Even though Suu Kyi may be one of the few Bamar that ethnic groups trust, they are under no illusions about their place in a unified Burma. "Let's say the Lady forms a government," says a senior commander of the Kachin ethnic group. "Will she love us as she loves [the Bamar] people? We will always be second-class citizens." Aung San Suu Kyi has said: "The ethnic problem will not be solved by this present constitution, which does not meet the aspirations of the ethnic nationalities," according to Press TV. [Source: Hannah Beech, Time, January 28, 2013]

flag of the Mon People

Aung San Suu Kyi has advocated a confederation with the ethnic groups. She said : "It is important in our movement for democracy that all ethnic groups in the country work together...Without this progress for the country will be impossible." In 2003, Aung San Suu Kyi visited representatives from at least a half dozen minorities, including the Kachin, Arakan, Shan, Chin and Mon. Aung San Suu Kyi supports crop substitutes for opium growers.

“When she was freed from house arrest in late 2010, Suu Kyi spoke of her desire to hold a second Panglong conference to discuss the future of the country’s ethnic minorities, who make up some 40 percent of Burma’s population. The first such confab, back in 1947, was convened by her father, independence hero General Aung San, who was assassinated before he could see his homeland wrest its freedom from Britain a year later. Back then, Aung San promised the three ethnic groups that participated in the conference (the Kachin, the Shan and the Chin) that they would be given significant autonomy in the new Union of Burma. The military junta that grabbed power in a 1962 coup ignored Panglong’s promises. Strife between ethnic militias and the Bamar-dominated central government characterized the next few decades. =

Drugs and Ethnic Groups in Myanmar

Among the main groups involved in opium growing and heroin processing in the frontiers of Myanmar have been 1) the army of the Shan drug lord Khun Sa; 2) the Shan United Army (SUA); 3) the Kuomingtang (KMT, remnants of the nationalist Chinese force that battled Mao's Communists); 4) the Wa (a tribe of former headhunters); and 5) the eastern Shan State army (a group of Kokang Chinese).

Many of these groups want independence from Myanmar and say that they are only in the drug trade as a mean of supporting their insurgent forces. Most of the these groups also have strong ties with members of their ethnic group on the Chinese side of the border, where some drugs flow on their way to Hong Kong and finally North America and Europe.

The Myanmar military regime has peace treaties with groups that supply heroin to America. The treaties with the Wa and the Kokang Chinese allows them to continue harvesting opium at least for several more years. Many oversees officials believe these treaties let the Myanmar military regime generals in on profits from the drug trade.

Many of the key operators in the heroin trade are structured like criminal gangs with an obsession for secrecy; have their own heavily armed private armies; and have legitimate businesses which they use as cover for the illicit transaction. One of Khun Sa's major lieutenants, Lin Chien-Pang for example, ran a karaoke club in Bangkok.

By the mid-1990s the trade was controlled mainly by the Wa, Shan and Kokang warlords. In the late 1990s and early 2000s it was controlled by the Wa

See Shan, Karen, Wa

Chinese and South Asians in Myanmar

Karen National Union Flag

The military Junta which ruled Burma for half a century, relied heavily on Burmese nationalism and Theravada Buddhism to bolster its rule, and, in the view of US government experts, heavily discriminated against minorities like the Rohingya, Chinese people like the Kokang people, and Panthay (Chinese Muslims).

There are about 800,000 Chinese living in Burma. They make up about 1.4 percent of the population of Myanmar. They make up 200,000 of Mandalay’s 1 million people. The Kokang are a Chinese group. Traditionally connected with Kuomintang, they supplied weapons in the Golden Triangle and were involved in the opium, heroin and amphetamines trade.

In the late and 1940s 1950s, internal struggles within the Burmese government was accompanied by struggles in the ethic states.. Exacerbating the problem was the conflict between the Kuomintang nationalists and the Communists in China. In 1949, the Communists defeated the Kuomintang and remnants of Chiang Kai-shek's defeated Kuomintang army retreated to the mountains of Burma along the Chinese border and tried to organize attacks against the Red Army from there. To raise money the Kuomintang encouraged peasant farmers to raise opium, which the Chinese nationalist sold for huge profits. This was the beginning of the Golden Triangle opium and heroin trade.

Forces made up of and aided by the Kuomintang became known as the White Flag Communists. They allied themselves with Shan fighters and fought some battles with Burmese government forces along the Chinese border.

There are at least one million South Asians in Myanmar but their true numbers are not known. Many are regarded as Bangladeshis, even Pakistanis, are not considered citizens of Myanmar (See Rohingya). Many of these are in Rakhine States (Arakan). There used to be a lot of Tamils in Myanmar. Many were members of the Nadukottain Chetti money-lending caste, who used to be major landowners in the Irrawaddy Delta.

Jews in Myanmar

As of 2001, there was a community of 20 Jews and one synagogue in Myanmar. Remnants of a once thriving community, they look like half Burmese and half Iranian and are members of eight families who live in Yangon. Among them is only one young marriageable man, Sammy Samuels. At that time he planned to stay in Myanmar to care of the synagogue and cemetery. To find a Jewish wife he needed to go abroad because the only young women in the Jewish community in Yangon were his sisters.

he Burmese Jews mostly arrived in the 19th century and were teak, cotton and rice traders and merchants. Most came from Iraq. Some also came from Iran and India.. At their height there were maybe 2,500 of them. Many fled Burma in World War II or after their businesses were nationalized in 1960s.Only Samuels can read Hebrew. Sometimes only three members of the community show up at the synagogue to observe the beginning of the Sabbath. One of the regulars told the New York Times, “Sometimes you feel very lonely, you feel sad. Sometimes its only me, only me in the big synagogue.”

The Musmeah Yesua synagogue is located in Yangon Muslim’s district among mostly Indian-owned hardware shops and paint stores. It is a two-story, white-washed structure built between 1893 and 1896, replacing an earlier wood structure built in 1854. Outside is a blue Star of David. Inside are some Israeli tourism posters and a photograph of the Wailing Wall and two 100-year-old copies of the Torah. A few blocks away is a Jewish cemetery with 60 moss- and jungle-covered tombstones. On holidays Jews often invite Buddhist, Muslim and Hindu friends to the synagogue

Muslims in Myanmar

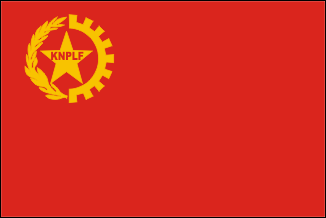

Karenni National People''s Liberation Front flag

The population of Myanmar is about 3.9 percent Muslim, including 250,000 residents of Mandalay and many people in the Arakan province near Bangladesh. Many are descendants of South Asian who came to Burma during the British colonial periodThe first Muslims in Burma arrived in the Arakan coast and the area around Maungdaw. Exactly when they arrived there is not known. Muslims then arrived in Burma's Irrawaddy River delta, on the Tanintharyi coast and in Rakhine in the 9th century, prior to the establishment of the first Burmese empire in 1055 AD by King Anawrahta of Bagan.

These early Muslim settlements were documented by Arab, Persian, European and Chinese travelers of the 9th century. Muslims arrived in Burma as traders or settlers, military personnel, and prisoners of war, refugees, and as victims of slavery. Many early Muslims also held positions of status as royal advisers, royal administrators, port authorities, mayors, and traditional medicine men. [Source: Wikipedia]There have been riots and violence between Muslims and Buddhists.

In Taungon a curfew was called after such rioting. In 1997, Buddhist monks and Muslims clashed in Mandalay. Monks stormed mosques and burned copies of the Koran and smashed furniture after a reported rape of a Buddhist girl. One monk was reported killed from a ricocheted bullet after police fired over protestors heads. Monks also attacked mosques in Yangon. Some observers believed the monks were actually soldiers because they wore army boots and carried mobile phones.The Royingyas from the Arakan region have been involved in promoting Islamic militancy. The government has been very secretive about their battle with them.

Buddhist and Burmese-Related Groups

There are only a few thousand of Danu who live in the Kalaw and Pindaya areas of Shan State and the Pyin Oo Lwin area of the Mandalay Division. Their language is a dialect of Burmese. The name Danu is derived from the word ‘Donke’ which means ‘brave archers’. The people in this area are named after the brave archers who settled here after fighting wars in Thailand. The Danu are farmers. they speak Burmese but with an accent. They also wear Burmese costume. [Source: Myanmar Travel Information]

Pagoda slaves in Myanmar are regarded as an Untouchable-like group. Other such groups include the Buraku in Japan, the Paekching in Korea, and the Ragyappa in Tibet.

The Tai Lue are an ethnic group associated mostly with the Xishuabgbanna region in the Yunnan Province in China but who have some members that live in Burma and Thailand. They are a subgroup of the Dai and are similar to the Thai and Lao. The have traditionally been rice cultivators and lived in tropical and semitropical monsoon forests along river valleys and in pockets of level land in the hill country of northeast Burma, northwest Thailand and southern China. See Dai, Minorities, China The Tai Lue are also known as Bai-yi, Dai, Lawam Lu, Luam Lue, Pai-I, Pai-yi, Shui Bai-yi, Shui Dai, Tai. There is no good information on Tai Lue numbers in Myanmar. In Thailand, there are maybe 100,000 of them and they live in communities scattered throughout northern Thailand. Nearly all Tai Lues are Theravada Buddhists. The Tai Lue language is very similar to the Lao and Thai languages. The written languages resembles Burmese.

See Rakhine People under RAKHINE STATE, SITTWE, MAGWE AND CHIN STATE factsanddetails.com

Small Tribes in Myanmar

A tribe of the Rawang people who live around the conjunction of Burma, India and China. There are only about 20,000 to 30,000 Rawang. They have long been primarily hunters and gatherers, but nowadays they also grow rice, serve as porters, and mine for gold and jade. The men Buddhist have used twigs or thorns as ear ornament. Women sometimes have a large silver ear-rings and have green tattoos around their mouths. [Source: Myanmar Travel Information]

Taron tribes inhabit the foot hills of Mt. Khakaborazi in the Himalaya mountain ranges. They have traditionally been a small people, averaging only 110 centimeters in here. Unfortunately the tribe has almost vanished. As of the early 2000s there was only full-blooded Taron man. The village of Taphungdan has no full-blooded Taron anymore but there are many Tarons who have married to other tribes. They are taller and have lost many of the physical signs of the Tarons. These “Tarons” practice shifting cultivation of rice, wheat, beans, maize, millet, mustard and yams. Extra produce is taken to market, together with medicinal herbs and tubers foraged in the jungle, in the district headquarters town of Putao. Trade in hides, antlers, bones and other animal parts flourishes across the Myanmar-China border.

The Zo ethnic tribes are an indigenous tribe, mostly found in Northern Chin State and in the Kabaw Valley of Western Sagaing Division in the Union of Myanmar. The Zo tribe has an estimated population of over 60,000. The are very much scattered in Myanmar and some other parts of the world. They are one of the official ethnic tribes in Myanmar. The Zo ethnics descend from the Main Tet Tibeto-Burman group of people. The ethnic group's name is believed to have been derived from the first person whose name was Pu Zo. Due to lack of evidence and difficulties in excavating archeological remains. the Zo's origins are difficult to be proved. Though widely believe to have descended from Mongolia. the routes to the present settlements are not clear. It is believed that the Zos have descended from Mongolia to China and to Tibet and to the present day Myanmar.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: East and Southeast Asia”, edited by Paul Hockings (C.K. Hall & Company); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2022