LISU ETHNIC GROUP

The Lisu are a fairly large ethnic minority that lives scattered over a relatively large area, living among other tribes and in remote places, in southwest China, northern Thailand, northern Laos, eastern Myanmar and northeast India. Traditionally slash and burn farmers, they reside in villages widely scattered among other groups and are regarded as one of the most colorful hill tribes in Southeast Asia. The Lisus, along with the Hmong, were one of the Golden Triangle's largest opium-producing tribes.

Lisu refer to themselves as Lisu or by clan names. They are also known the Aung, Lisuchang, Che-nung, Khae, Lisaw, Khae Liso, Lasaw, Lashi, Lasi, Le Shu O-op’a, Lesuo, Leur Seur, Li, Li-hsaw, Lip’a, Lipo, Lisaw, Li-shaw, Lishu, Liso, Loisu, Lusu, Lu-tzu, Shisham, Yaoyen, Yawyen, Yawyen, Yawyin and Yeh-jen. The Lisu are known by so many names because they are so widely scattered and live among so many groups, many of which have their own names for the Lisu. [Source: Alain Y. Dessaint, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Lisu live mostly in the western part of Yunnan Province in China but are scattered across the valleys of Nujiang (Salween) and Langcang (Mekong) rivers of China and are found in the neighboring countries as far west as eastern Tirap (at the extreme northeast corner of India) and as far south as Kamphaeng Phet and Phitsunulok in Thailand. The Lisu usually live in mountainous areas, with deep valleys and difficult communications. Along the Nujiang and Lancang Rivers some of their villages are situated at an altitude of more than 4,000 meters.

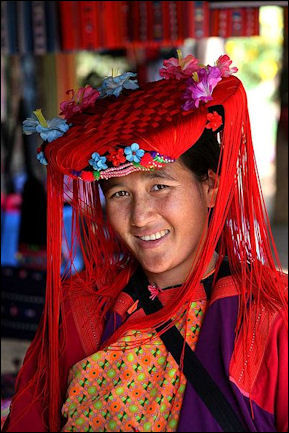

The Lisu are mostly farmers. In the past they had a reputation for being hunters and warriors that enslaved other minorities. Corn and buckwheat are their staple foods. They like to drink tea, wine and eat big chunks of meat. Their dress and personal adornments are different in different areas. In the past, the Lisus were commonly called "White Lisus", "Black Lisus" and "Flowery Lisus" because of their different clothes colors. "Communications between different Lisu communities over the centuries has been difficult, which explains their division into so many distinctive subgroups."

The Lisu are very short — about four inches shorter than your average Han Chinese. The Lisu have been described as a "fine" people: robust, independent of spirit, and excellent warriors. According to the Chinese government: “The Lisus are industrious and valiant. In history, they rose in rebellion for resisting class exploitation, national oppression, and foreign invasion from English, Japanese. They fight movingly time and again and made great contribution to the protection and construction of the Southwest China.”[Source: Frontline, pbs.org, April 22, 2006; China.org]

See Separate Articles: LISU STORIES AND FABLES factsanddetails.com LISU LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Book Chinese Minorities stanford.edu ; Chinese Government Law on Minorities china.org.cn ; Minority Rights minorityrights.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Ethnic China ethnic-china.com ;Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; Travel China Guide travelchinaguide.com ; China.org (government source) china.org.cn ; People’s Daily (government source) peopledaily.com.cn ; Paul Noll site: paulnoll.com ; Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China Books: Ethnic Groups in China, Du Roufu and Vincent F. Yip, Science Press, Beijing, 1993; An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China, Olson, James, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1998; “China's Minority Nationalities,” Great Wall Books, Beijing, 1984; “Women Not to be Blocked by Canyon: The Lisus” by Yang Guangmin is a booklet put out in 1995 by the Yunnan Publicity Centre for Foreign Countries as part of the a “Women’s Culture series, which focuses on different ethnic groups found in Yunnan province. The soft-cover 100-page booklet contains both color photographs and text describing the life and customs of women. The series is published by the Yunnan Publishing House, 100 Shulin Street, Kunming 65001 China, and distributed by the China International Book Trading Corporation, 35 Chegongzhuang Xilu, Beijing 100044 China (P.O. Box 399, Beijing, China).

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Lisu: Far from the Ruler” by Michele Zack Amazon.com; “Peoples of the Greater Mekong: the Ethnic Minorities” by Jim Goodman and Jaffee Yeow Fei Yee Amazon.com ; “Ethnic Oral History Materials in Yunnan” by Zidan Chen Amazon.com; “Women Not to be Blocked by Canyon” by Yang Guangmin (1995) Amazon.com; “Lonely Planet Hill Tribes Phrasebook & Dictionary” by David Bradley , Christopher Court, et al. (2019) Amazon.com; “Songs of the Lisu Hills: Practicing Christianity in Southwest China” by Aminta Arrington and Brian Stanley Amazon.com; “Faith by Aurality in China’s Ethnic Borderland: Media, Mobility, and Christianity at the Margins” by Dr. Ying Diao Amazon.com; “Children of the Hills” by Isobel Kuhn Amazon.com; “Run for the Mountains” by Gordon Young Amazon.com

Lisu Population and Places They Live

The total population of Lahu is estimated to be at 1.4 million people, with 700,000 in China, 5,000 in Arunachal Pradesh in India, 55,000 in Thailand and 600,000 in Myanmar. In 1989, there were an estimated 481,000 Lisu in China, as many as 250,000 in Myanmar (where there has never been a reliable census), about 18,000 in Thailand, and several hundred in India. About two thirds of the Lisu live in western Yunnan Province in China in the mountains between the Salween and Mekong River. Most are in the Fujian Lisu Autonomous Prefecture. Others are scattered across a dozen or so counties in Yunnan and Sichuan. In Myanmar, Lisu live in northern (Namhsan, Lashio, Hopang, and Kokang) and southern Shan State (Namsang, Loilem, Mongton) and Wa Special Region, Sagaing Division (Katha and Khamti), Mandalay Division (Mogok and Pyin Oo Lwin), and Kachin State (Putao, Mkyikyina, Waimaw. [Source: Alain Y. Dessaint, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Lisu are the 21st largest ethnic group and the 20th largest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered 702,839 in 2010 and made up 0.05 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Lisu populations in China in the past: 635,101 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 574,856 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 317,465 were counted in 1953; 270,628 were counted in 1964; and 466,760 (480,960) were, in 1982. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

In China, the Lisu live mainly in concentrated communities in Bijiang, Fugong, Gongshan, Lanping and Lushui counties of the Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture in northwestern Yunnan Province. The rest are scattered mostly in Lijiang, Baoshan, Diqing, Dehong, Dali, Chuxiong prefectures or counties in Yunnan Province as well as in Xichang and Yanbian counties in Sichuan Province, living in small communities with the Han, Bai, Yi and Naxi peoples. Lisu are scattered in over 30 counties in Yunnan Province, including Zhongdian, Deping, Weixi, Lijiang, Yongsheng, Huaping, Ninglang, Yangbi, Tengchong, Longchuan, Ruili, Lianghe, Luxi, Lincang, Genma, Chuxiong, Yuanmou. In Sichuan Province they can be found in Xichang, Muli, Yanyuan, Yanbian, Miyi, Huili, and Huidong. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences; China.org |]

The main area the Lisus inhabit is a mountainous area slashed by rivers and characterized by deep valleys and river gorges. The region is flanked by Gaoligong Mountain on the west and Biluo Mountain on the east, both over 4,000 meters above sea level. The Nujiang River and the Lancang River (Mekong River) flow through the area, forming two big valleys. The average annual temperature along the river basins ranges between 17 and 26 degrees Centigrade, and the annual rainfall averages 2,500 millimeters. Main farm crops are maize, rice, wheat, buckwheat, sorghum and beans. Cash crops include ramie, lacquer trees and sugarcane. Many parts of the mountains are covered with dense forests, famous for their China firs. In addition to rare animals, the forests yield many medicinal herbs including the rhizome of Chinese gold thread and the bulb of fritillary. The Lisu area also has abundant mineral and water resources. |

Early Lisu History

Lisu in the 1900s

The Lisus have very long history. According to historical records and folk legend, the forbears of the Lisu people lived along the banks of the Jinsha River and were once ruled by "Wudeng" and "Lianglin," two powerful tribes. [Source: Alain Y. Dessaint, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Lahu are believed to be related to the Qiang and are one of the first ethnic groups to be chronicled in Chinese historical record. They were referred to in the 12th century B.C. and originated from the western plains near the mountains in Gansu where the Qiang lived. The Qiang gave birth to the Lo-Los, a tribe which once had a number of independent kingdoms in the eastern Tibet and the Sichuan region of China. Some anthropologists believe the ancestors of the Akha, Lisu and Lahu descended from the Tibetan highlands in the second century B.C. after some of them lost their ability to deal with the harsh cold.

The Lisu were mentioned in Chinese historical records, dated to A.D. 685 as one of the “southern Barbarians” of Yunnan and Sichuan. They were associated with the area around the Jinsha River in northwestern Yunnan.The earliest description of the Lisu are found in books written in Tang Dynasty. According to Tang Dynasty history books in Lisu, variously called Wuman, Lisu Man, Shi Man, Shun Man, inhabited in a wide area which is now includes the Yabi River, Jiansha River, Canglang River in Sichuan and Yunnan Province.

Later History of the Lisu

Much of Lisu history is defined by their interrelation with the Chinese. This relationship involved raids, banditry, warfare, suppression and enslavement as well as intermarriage and trade of medicinal herbs, bear gall bladder, stag horns, beeswax and forest food by the Lisu for salt, iron and foodstuffs from the Chinese. Mostly the imperial Chinese dominated the Lisu through the tusi (native chief) system. According to a Lisu legend this relationship began after the Great Flood many thousands of years ago when the Lisus found themselves living next to the Chinese. To determine who would rule the land the Lisu and Chinese leaders devised a test — each leader would plant a rod in the jungle and whoever's rod bloomed first would rule. After the planting ceremony everyone went to sleep. The unscrupulous Chinese leader awoke first and upon seeing that the Lisu rod had already blossomed he exchanged it with his own. [Source: Alain Y. Dessaint, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

During the Yuan and Ming Dynasty, the Lisus were under control of the Naxi feudal chieftains in Lijiang and other places under the tusi system in which minorities were ruled by hereditary chiefs and headmen approved by the central government in the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties. During the mid 1600s, the Lisus could not stand living under the slavery and oppression of the local Naxi chieftains and the tusi system. Led by the headman, Mubipa, the Lisus crossed Canglang River, climbed over the Piluo snow-capped mountains and eventually arrived in Nujiang River area. For the next two centuries, the Lisus experienced several migrations due to escape from repression and defeated revolts.

According to the Chinese government: “After the 12th century, the Lisu people came under the rule of the Lijiang Prefectural Administration of the Yuan Dynasty, and in the succeeding Ming Dynasty, under the rule of the Lijiang district magistrate with the family surname of Mu. During the 1820s, the Qing government sent officials to Lijiang, Yongsheng and Huaping, areas where the Lisus lived in compact communities, to replace Naxi and Bai hereditary chieftains. This practice sped up the transformation of the feudal manorial economy to a landlord economy, and tightened up the rule of the Qing court over Lisu and other ethnic groups. In the years preceding and following the turn of the 20th century, large numbers of Han, Bai and Naxi peoples moved to the Nujiang River valleys, taking with them iron farm tools and more advanced production techniques, giving an impetus to local production. [Source: China.org|]

“For a long time the Lisus, under oppression and exploitation by landlords, chieftains and headmen, as well as the Kuomintang and foreign imperialists, led a miserable life. In Eduoluo Village of Bijiang County alone, 237 peasants out of the village's 1,000 population were tortured to death in the 10 years prior to liberation by local officials, chieftains, headmen or landlords. The Lisus also suffered exorbitant taxes and levies. The household tax, for example, was 21 kilograms of maize per capita, accounting for 21 per cent of the annual grain harvest. Moreover, there were unscrupulous merchants and usurers. The arrival of imperialist influence at the turn of the 20th century put the Lisus in a far worse plight. During the period between the 18th and 19th century, the Lisus waged many struggles against oppression. From 1941 to 1943, together with the Hans, Dais and Jingpos, they heroically resisted the Japanese troops invading western Yunnan Province and succeeded in preventing the aggressors from crossing the Nujiang River, contributing to the defense of China's frontier.” |

Lisu Migrations

Lisu in 1921

Beginning in the 16th century the Lisu undertook three major migration, finally settling in the valleys of the Lancang and Nujiang River in China and mixing and with communities of Han, Bai, Nu, Li and Naxi people. The Lisu migrated in the area along the Golden Sands River (Jinsha River). More technically advanced and better organized, they overpowered and pushed out the indigenous people of the Nu River area, forcing them to pay tribute and enslaving some of them. Advancing in a southwesterly direction they came into increasing contact with Bai, Naxi, Jingpo, and Dai peoples and in some cases became subservient and were enslaved by them, but mostly they sought refuge in the upper slopes of the mountains. [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Naranbilik, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

The migration of the Lisu into Burma, Thailand and India began in the late 19th century . The Lisu that came to Thailand arrived from the Shan states in Burma in the early 20th century. In the years preceding and following the turn of the 20th century, large numbers of Han, Bai and Naxi peoples moved to the Nujiang River valleys, At the beginning of the 20th century, some western missionaries came to the Nujiang and Dehong regions and Christianity was spread into these areas.

Chinese pacification efforts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries after the Taiping Rebellion, (1850-1864) and other wars and revolts in southern China caused large-scale movements of Lisu into Burma, and later Thailand and India. This movement of Lisu peoples south and east and appears to have been connected with the opium trade and deteriorating relations with the Chinese. Oral traditions of the Lisu in Thailand indicate that the first families arrived there from Burma between 1900 and 1930, motivated by the search for good high-elevation opium lands and a wish to escape unsettled conditions in China and Burma. [Source: Alain Y. Dessaint, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

The Lisu have been very adaptable and quick to learn the languages and ways of their neighbors. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ Some, especially in Myanmar and Thailand, have even intermarried with Chinese, Lahu, and Kachin, recognizing a fictitious equivalence of Lisu clans and lineages with those of neighboring ethnic groups. Chinese operate stores or caravan routes in Lisu villages, and the Lisu patronize local markets. Lisu have served in the British Burma army, the People's Liberation Army, and the Thai Border Patrol Police. Christian and Buddhist missionaries among the Lisu have not been very successful.

Mysterious Lutzos

In their 1918 book “Camps and Trails in China,” describing their search for zoological specimens in Yunnan, Roy Chapman Andrews and Yvette Borup Andrews, wrote: “Our second camp was on the river at the mouth of a deep valley, near a small village. Wu said that the natives were Lutzus and I was inclined to believe he was right, although Major Davies indicates this region to be inhabited by Lisos. At any rate these people both in physical appearance and dress were quite distinct from the Lisos whom we met later. They were exceedingly pleasant and friendly and the chief, accompanied by four venerable men, brought a present of rice. I gave him two tins of cigarettes and the natives returned to the village wreathed in smiles. The garments of the Lutzus were characteristic and quite unlike those of the Mosos, Lisos or Tibetans. The women wore a long coat or jacket of blue cloth, trousers, and a very full pleated skirt. The men were dressed in plum colored coats and trousers." [Source: Roy Chapman Andrews and Yvette Borup Andrews, “Camps and Trails in China: A Narrative of Exploration, Adventure, and Sport in Little-Known China, 1918; Ethnic China]

According to "An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China": "The Lusu (Lu-tzus), a subgroup of the Lisu people of Yunnan Province... are found primarily... between the Salween and Mekong rivers in western Yunnan Province- Their language is not mutually intelligible with most of the other Lisu tongues, but it is closely related to Akha, Lahu, and Yi. Lusus are more likely to identify themselves as ethnic Lusus than Lisus. Their social system revolves around a variety of patrilineal, exogamous clans which exercise great political power." [Source: Olson, James S.. Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China. Greenwood Press, Westport, 1998]

Lisu Under the Communist Chinese

Lisu Autonomous areas in Yunnan in China

After the formation of the People's Republic of China in 1949, army units and government cadres arrived to administer Lisu areas. The Communist Chinese established the Nuchiang Lisu Autonomous region, abolished slavery and the debts the Lisu owed in 1956. Chinese influence on Lisu culture, already strong before 1949, gained momentum. Opium growing was banned and double cropping, manuring, irrigation and other Chinese-stye agriculture methods were imposed.

Development also brought new tools, roads, bridges, clinics, , schools and the development of political consciousness that included Lisu cadres, soldiers, and Communist Party members. The commune system of agriculture was not well received by the Lisu and was quickly abandoned These changes caused great stress, particularly during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, when "local nationalism" was criticized and rapid movement toward socialism demanded. [Source: Alain Y. Dessaint, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

According to the Chinese government: “The social economy in the various Lisu areas was at different levels before China’s national liberation in 1949. In Lijiang, Dali, Baoshan, Weixi, Lanping and Xichang, areas closer to China's interior, a feudal landlord economy was prevalent, with productivity approaching the level in neighboring Han and Bai areas. Some medium and small slave-owners had appeared from among the Lisus living around the Greater and Lesser Liangshan Mountains, taking up agriculture or part-agriculture and part-hunting, and using ploughs in farming. [Source: China.org|]

“As for the Lisus living in Bijiang, Fugong, Gongshan and Lushui, the four counties around the Nujiang River valley, their productivity was comparatively low. They had to make up for their scanty agricultural output by collecting fruits and wild vegetables and hunting. Their simple production tools consisted of iron and bamboo implements. Slash-and-burn was practiced. The division of social labor was not distinct, and handicrafts and commerce had not yet been separated from agriculture. Bartering was in practice. Some primitive markets began to appear in Bijiang and Fugong counties. |

Lisu Clans and Patriarchal Slavery

According to the Chinese government: “Patriarchal slavery existed in the Nujiang River area in the period between the 16th century and the beginning of the 20th century. The slaves were generally regarded as family members or "adopted children." They lived, ate and worked with their masters, and some of the slaves could buy back their freedom. The masters could buy and sell slaves, but had no power over their lives. The slaves were not stratified. All these reflected the characteristics of exploitation under the early slavery system. [Source: China.org |]

“In post-1949 days, the remnant of the clan system could still be found among the Lisus in the Nujiang River valley. There were more than a dozen clans there, each with a different name. They included Tiger, Bear, Monkey, Snake, Sheep, Chicken, Bird, Fish, Mouse, Bee, Buckwheat, Bamboo, Teak, Frost and Fire. The names also served as their totems. Within each clan, except for a feeling of kinship, individual households had little economic links with one another. |

“The clan and village commune played an important part in practical life. The "ka," or village, meant a place where a group of close relatives lived together. Some villages were composed of families of different clans. Every village had a commonly acknowledged headman, generally an influential elderly man. His job was to settle disputes within the clan, give leadership in production, preside over sacrificial ceremonies, declare clan warfare externally, sign alliances with other villages, collect tributes for the imperial court. Under the rule of a chieftain, such headmen were appointed his assistants. When the Kuomintang came, they became the heads of districts, townships or "bao" (10 households). When there was a war, the various communal villages might form a temporary alliance; when the war was over, the alliance ended. |

“Apart from common ownership of land and working on it together, clan members helped one another in daily life. When there was wine or pork, they shared it. When a girl got married, they shared the betrothal gifts given to her parents; and when a young man took in a wife, the betrothal gifts for the bride's family were borne by all. Debts too, were to be paid by all. These collective rights and obligations in production and daily life made it possible for clan relations to continue for a long time.” |

Lisu Language and Bamboo Books

Lisu in Chinese characters

The Lahu and Lisu speak a language in the Central Loloish (or Yi) branch of the Lolo-Burmese subgroup of the Tibetan-Burmese branch of Sino-Tibetan languages. It is closely related with the Yi and Naxi languages. The Hani (Akha) speak a Southern Loloish language. The Lisu language has two dialects whose speakers can communicate without difficulty: the Weixi dialect and Nujiang dialect.

The Lisu traditionally had no written language. Chinese and missionaries have developed Roman-based, and Chinese-based scripts for the Lisu language. A script for the Lisu language, based on Latin letters, was only developed in 1957 by the Chinese government. It replaced both a missionary-devised alphabetized system and one based on Chinese ideographs that had limited use prior to 1949. Some Lisu are literate in Thai and Chinese The Lisus say they had an ancient language written on skins but it lost after the skins were eaten by a dog. Many Lahu men can speak several languages, especially Chinese, Lahu, Shan, Yuan (northern Thai-Lao) and Akha. There are numerous Lisu titles.

The Lisu have three kinds of writings. One is alphabetic writing formulated by western missionaries; another is syllabic writing created by peasants of Weixi county; and the third is Latin alphabet system formulated with the help of the Chinese government in the 1950s. The written language created in Weixi consists of about 500 pictographic characters. The written language created by missionaries working in the Nujiang River during the first decades of 20th century was mainly used for religious activities. Some years later missionaries working with the Lisu in Wuding County developed a new Lisu writing, also with religious purposes in mind: namely to promoted the Bible and Christianity.

The Lisu pictogram written language was devised—as a response to foreign attempts to create a Lisu script based in faraway traditions in foreign lands—by Wang Zepo a Lisu from Weixi County. As most of the Lisu characters were engraved in bamboo, the books written in this script became known as "the bamboo books of the Lisu." Most of the bamboo books had a religious purpose, but, as opposed to the foreign scripts, the books are related to the Lisu traditional religion, with titles such as "The Creation of the World", "The Tale of Kamaba", "The Orphan and the Dragon Princess", or scriptures praying for water or good harvest. [Source: Ethnic China]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “Most of the 243 characters developed by Wang Zepo are completely original, though most of them were inspired by the scripts known to him: Chinese characters of the Han Chinese and Dongba and Geba scripts of the Naxi people. In some Lisu characters the similarity with these other systems of writing is evident, but most of them have been developed to form as a whole a completely different script. He created also some completely new characters, most of them pictographic. Cucumber (pu in Lisu), for instance, is represented as the cucumbers hanging from the vine. The Bamboo scrip is a syllabic scripture. Every syllable of the Lisu language can be written with one of the characters developed by Wang Zepo.” [Source: All the information about the Bamboo books of the Lisu of this short note has been extracted from the book of Gao Huiyi Lisu zu zhushu wenzi yanjiu (Researches on the script of the bamboo books of the Lisu). Published by Huadong Normal University Press, Shanghai, 2006]

Lisu Religion

Lisu Button Disc

The Lisu have traditionally believed in a spirits associated with natural phenomena and deceased human beings. Great care was taken not to offend the spirits thought to have the power to cause illness and bring misfortune. Each village has its own primary spirit. Divinations with pig livers, chicken femurs and bamboo dice were traditionally performed before important activities such building a house or embarking on a hunting trip.

Lisu religion has traditionally been dominated by totemism and animism, though after the arrival of Western Christian missionaries in early of 20th century, many Lisu were converted to different branches of Christianity. Lisu have traditionally believed to that every single thing has a soul: plants and animals, natural objects and phenomena, everyday items and all people. [Source: Ethnic China *]

The Lisu also have traditionally believed that everything has a god, spirit or genie—“ni” or "ne" in the Lisu language—who directs its actions. Some of the main divinities of the Lisu are: 1) Baijiani, the god of Heaven; 2) Haikuini, the god of the Hearth; 3) Mijiani, the god of the Dreams; and 4) Misini, the god of the Mountains. Misini has traditionally been one of their most important deities, as he governs the hunt. There are also a lot of lesser gods, devils, and spiritual creatures that are difficult to define as well as genies associated with their enemies: the Naxi and Leimo. Every deity has its own rituals. *\

The Lisu concept of religion—that is, the relationship between people and their gods— is more practical than metaphysical. With supernatural powers that can influence the life of the people, the main question is to know how to avoid disturbing them and, if they are disturbed, how avoid their ill effects. As for human souls, a person starts to live when the soul joins the body. After the body dies, the soul left behind. Bodiless souls can interact with living people, helping them or causing some harm. To prevent these souls from becoming dangerous, ceremonies are performed to ask the souls to be good ones. *\

Lisu Shaman

Some Lisu villages have a shaman. His primary responsibility is contacting deceased ancestors and spirits to seek their help to cure the sick. In a typical healing ceremony a shaman goes into a trance, invokes the spirt associated with the disease the person is suffering from and calls on the family of the sick to sacrifice a pig or chicken.

The Lisu have two kinds of shamans—the Niba (ne pha ) and the Niguba—that act as intermediaries in the difficult relations between human beings and spirits The Niba enjoy high social status. They know the history and old myths of the Lisu, while the Niguba work in a more intuitive way. These shamans know more than ten different ways of know the will of the gods. Lisu people consider that the dreams are very important, because dreams are a kind of communication between humans the world of spirits and souls. According to the Chinese government: “ Religious professionals made a living by offering sacrifices to ghosts and fortune-telling. During the religious activities, animals were slaughtered and a large sum of money spent. “ [Source: China.org, *]

Religion is generally the domain of males. Any male may become a shaman if he has an ability to contact ancestors and other spirits useful in curing the sick, and if he passes initiation tests by other shamans. He has no inherent power and receives little in terms of payments. Most traditional villages have a shaman-priest (mu meu pha )who is chosen through divinations. He keeps track of events scheduled by the lunar calendar and presides over rituals. [Source: Alain Y. Dessaint, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Lisu Funerals

Sword pole The dead have traditionally been buried. Generally the village or the clan had its own common graveyard. For a man, the cutting knives, bows and quivers he had used when alive were buried with him. For a woman, burial objects were her weaving tools, hemp-woven bags and cooking utensils, to be hung by her grave. [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Naranbilik, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

When an elderly man or woman died, the whole village stopped working for two or three days. People tendered condolences to the bereaved family, bringing along wine and meat. Generally the mound on the burial ground was piled one year after the burial, and respects to the dead were paid three years after the burial, and offerings ended. [Source: China.org |]

At funerals, prayers are recited and ritual offerings are made with the aim of speeding the soul on its journey to the next world. Those who died in violent deaths or accidents are given exorcisms. The Lisu believe the spirit of dead person is potentially dangerous for three years. Ancestor spirits are honored with regular offerings of rice liquor, joss sticks and ragweed.

Lisu Festivals and Calendar

Festivals and holidays are set to lunar calendars on schedules that often differ from village to village. Lunar New Year is the is the biggest celebration of the year. It last several days and includes feasting, courtship rituals, displays of fine clothes and jewelry. Tree-renewal ceremonies are held to purge malevolent spirits and create a comfortable environment for protector spirits.The Sword-Pole Festival is held on the eighth day of the second lunar month. Participants climb a ladder made of swords in their barefeet.

The Lisu developed a calendar applicable to their local agriculture cycle and climate. Because it is in tune with blossoming of flowers and songs of birds, it is called the Flower Bird Calendar. According to this calendar the year is divided into ten months: 1) blossom month, 2) birdcall month, 3) mountain burnt month, 4) hungry month, 5) collection month, 6) harvest month, 7) vintage month, 8) wedding feast month, 9) spring festival month and 10) building house month. If the months are of equal length and the Lisu year corresponds to a solar then there are roughly 36 or 37 days in each of the ten months. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

The festivals of the Lisus are closely linked with those of the Han, Bai, Naxi and other peoples around them. During the Lunar New Year, the first thing they do is to feed their cattle with salt to show respect for their labor. They have the Torch Festival in the sixth lunar month and a Mid-Autumn Festival in the eighth lunar month. The Lisus in the Nu River and Weixi areas enjoy their "Harvest Festival" in the 10th lunar month, during which people exchange gifts of wine and pork. They sing and dance till dawn. [Source: China.org |]

Their main Lisu festivals are the "Bathing Pool Party", "New Product Tasting Festival", "Kuoshi Festival" ( Lisu New Year), "New Rice Festival", "Knife Stalk Festival", "Torch Festival", "Harvesting Festival", “Swords-Pole Festival,” Singing Festival (featuring a kind of antiphonal singing, alternate singing by two choirs or singers) and "Crossbow Shooting Festival". Swords-pole festival is held on the 8th day of the 2nd lunar month. People dress in their new clothes and gather to watch performances of climbing mountains of swords and rushing into the seas of flames.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, ~]

The "Bathing Pool Singing Gathering", also called the "Spring Bathing Festival", is traditional Lisu festival and grand meeting. Now it is usually held in the first lunar month at the hot springs of Denggen and Mazhanghe about 10 kilometers from Liuku city, is the capital of Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture. Not only Lisus but members of other ethnic groups, from nearby counties and regions, wearing rich clothes and bringing food, camping gear and cooking stuff, pour in. Tents are set up all over the place, ceating a carnival atmosphere in a place that is normally quiet. The "Spring Bathing Festival" used to be a time to take bathes and cure diseases, now it is time for revelry, dancing and singing, especially for youths who gather together in dozens or even hundreds to participates in song competitions, recite poems and look for lovers. ~

Men take bath in the upper hot spring pools and females take their in the lower pools, which are far from each other. Some may prefer to take a shower in the spring for five or six times, because they believe this is the only way to get rid of diseases and improve their immune systems. Lisus have come to the hot springs around Liuku for more than a hundred years. Lisus singers from several miles away would also get together to sing and give performances while people sit around campfires and drink mild sweet rice wine. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

The Lisu celebrate a torch festival in which participants light torches in front of their houses and set large fires in their village squares. The festival honors a woman who leaped into a fire rather make love with a king. Before the village torch is lit people gather around it and drink rice wine.

Kuoshi Festival ( Lisu New Year)

The "Kuoshi Festival", also called the " Heshi Festival", celebrates the Lisu new year. "Kuoshi" is translation of the Lisu language, which means " the beginning of new year" or " the new year". It is the grandest traditional festival for the Lisus. People used to decide the day of celebration by observing natural phenomenon, so different places often celebrated New Year's Day on different days. Usually the Kuoshi Festival falls in a ten-day period in late December or early January in accordance with the Gregorian calendar. Beginning in 1993, the government of the Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture decided that the "Kuoshi Festival" would be celebrated from the 20th to 22nd of December, so that Lisu people could welcome the New Year and celebrate the festival at the same time. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

During the festival, people generally make wine, butcher chickens and pigs and pound cakes. All kinds of foods are prepared. Pine boughs are broken and inserted into the doors, the number of which indicates the number of men in the house. The boughs are there to get rid of diseases and bring happiness and good luck. A big family dinner is held on New Year's Eve. If someone is in another place far from home, the family members leave a seat for him and put a bowl and a pair of chopsticks out for him. In some places, people are not allowed to go to others' homes, even if they are close family members, until the third day of the New Year. In most places, people gather outside in a sunny place and engage in various kinds of recreational activities, such as singing in antiphonal style, dancing, swinging and crossbow-shooting. ~

The Lisus have traditionally fed dogs the first piece of pounded cake in the "Kuoshi Festival". It's said that this is to thank dogs for " bringing grain seeds to the human world". There are many legends about dogs and grain seeds among the Lisus. For example: in ancient time, human beings wasted too much grain. The main god was very angry about this, so he ordered that all the grain be taken back to the Heaven. Human beings only faced starvation they were also experienced a huge flood. Just when it seemed all was lost a dog leaped ahead, not fearing its own safety, and climbed up a pole to Heaven, stole grain seeds and brought them back to Earth and saved human beings. ~

Swords Pole Festival

The Swords-pole festival is held on the 8th day of the 2nd lunar month. People dress in their new clothes and gather to watch performances of climbing mountains of swords and rushing into the seas of flames. There is a famous Lisu story about the origin of the Swords Pole festival. among the Lisus. Once upon a time, the Han and the Lisus were brothers born by the same mother. When they grew up and got married, they planned to live individually so the Han elder brother enclosed a piece of field by making a stone fence, while the Lisus younger brother enclosed the field with a grass rope. However, after a big mountain fire, the stone fence was still there, but the grass rope burned down. The Lisus could not recognize his own field, so he had to move into the deep mountains and live on hunting and planting corns. Their life was really tough; what's more, they were frequently attacked by robbers from far away places. The Lisus had a hard time defending themselves. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

At this time, the central government sent for the Minister of Military, Mr. Wangji to the frontier. With the help of the Lisus, Wangji's troops defeated foreign invaders and protected the border region. Wangji helped the Lisus who lived in the deep mountains to live together and form villages. In addition, Wangji also taught the Lisus advanced agriculture techniques, cattle breeding, trees planting, which made a much better life for the Lisus. Meanwhile, Wangji singled out strong Lisu men and provided them with military training. \=/

After a few years of peaceful life, an unexpected disaster happened. Treacherous court officials presented several documents to the Chinese emperor, which stated falsely that Minister of the Military Wangji was gathering an army to betray the country. The emperor believed the treacherous court officials' words and ordered Wangji to come back to the court for punishment. On the 8th day of the 2nd lunar month, the treacherous court officials made a banquet to welcome Wangji and put poison into his drink. Wangji died. Whe Lisus heard the bad news they were very sad and burning with righteous indignation. They promised they would honor Wangji by climbing sword mountains and rushing into the fire sea.

Crossbow Contests and Burying Lovers in the Sand

"Sand of the river buries the lover" is a traditional entertainment and spouse seeking practiced by Lisu in the Fugong region of the Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture. It is held on the forth or fifth day of the New Year. Young men and women gather by the Nujiang River, dancing, singing and playing. Helped by their friends, they dig pits in the sand beach and "bury" their boyfriends and girlfriends in the sand. They pretend to be very sad, weeping, singing mourning songs and dancing mourning dances. After a while they pull their boyfriends and girlfriends out make full fun of them. The idea behind the ritual is to: 1) show their deep and sincere love; and 2) bury the "Death" in their lovers' bodies and make them healthy and live long.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Lisu youths in the Fugong region also hold crossbow-shooting matches called "shooting eggs on the head". During these matches, men hold crossbows in their hands; their girlfriends place a bowl upside down on their heads and put an egg on it (or put a wood bowl on their head and put some rice and an egg in it), and stand several meters away. When the match begins, a young man pulls the bowstring, puts an arrow on it unhurriedly and shoot it. When the arrow hits its target liquid in the egg splashes out, and the girl is safe and sound—to everyone’s relief. Suddenly, warm applause spreads out from the site. This is a soul-stirring and exciting sight, demonstrating skill, courage, true love and perhaps most of all, trust. Those that are not skilled play it safe, preferring to miss the target than hurt their lovers. ~

Image Sources: Nolls China website , Joho maps, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022