KAREN LIFE AND CUSTOMS

General Etiquette: 1) The Karen are more conscientious towards people than time. 2) Public displays of affection between males and females is discouraged. 3) People remove their shoes when they enter a home. 4) One should pass things with the right hand. 5) Being direct is considered rude. [Source: Courtney Imran, Karen Culture, Des Moines Public Schools =]

Education for Karen in Burma was initially provided in Buddhist monasteries and missionary schools. The latter devised a Karen script based on Burmese and also taught English and Burmese. The Burmese and Thai governments have promoted the establishment of government schools in Karen villages and towns, where Karen children are sent to attend secondary school.

Karen school life: 1) Teachers move between classes and students remain in the same room. 2) Students learn a lot through song. 3) Students receive a lot of homework. 4) Schools use corporal punishment. 5) There are usually at least 30 students per class. 6) Students receive rankings in every grade, and the top student receives a prize at the end of the year. =

The Karens are avid smokers. In many cases, once a child is old enough to hold up a pipe, he or she begins to smoke. Many also chew betel nut. Cerebral malaria and hair lice are endemic in many areas where the Karen live.

Karen have traditionally believed that the causes of illness and death were spiritual and sickness results when evil spirits lure the soul from the body. Among the Sgaw Karen, illness is a devise used by spirits of places (da muxha ) and spirits of the ancestors (sii kho muu xha ) to signal their displeasure or their desire to be fed. K'la (the soul) can become detached from human bodies during vulnerable times such as sleep or contact with the k'la of a person who has died, and must be ritually brought back to the body to avoid illness or even death. [Source: Nancy Pollock Khin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993|]

The job of healers is to bring the soul back. Sometimes divinations using chicken feathers, bones, eggs, or grains of rice are are used to figure out the spiritual source of an illness and determine the best treatment. In the case soul loss, a shaman is summoned to perform a soul-calling ceremony. There are also rites of propitiation for various nature and ancestor spirits that cause illnesses. Karen use herbal and animal-derived medicines.

See Separate Articles KAREN MINORITY factsanddetails.com ; KAREN INSURGENCY factsanddetails.com ; KAREN REFUGEES factsanddetails.com ; LUTHER AND JOHNNY: MYANMAR 'GOD'S ARMY' TWINS factsanddetails.com ; PADAUNG LONG NECK WOMEN factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Karen People of Burma: A Study in Anthropology and Ethnology” by Harry Ignatius Marshall Amazon.com; “The History of the Karen People of Burma” by Angeline Naw and Jerry B. Cain Amazon.com; “The "Other" Karen in Myanmar: Ethnic Minorities and the Struggle without Arms” by Ardeth Maung Thawnghmun Amazon.com; “Hpu Htawt Me Pa (Grandpa Boar Tusk) & The Magical Comb (Karen Folk Tale) by Sally Myint Oo Amazon.com; “Karen Language Phrasebook: Basics of Sgaw Dialect” by T F Rhoden Amazon.com; “Trilingual Illustrated Dictionary: English-Myanmar-Karen” by U Thi Ha and Daw Thida Moe Amazon.com; “Lonely Planet Hill Tribes Phrasebook & Dictionary” by David Bradley , Christopher Court, et al. (2019) Amazon.com; “The Hill Tribes of Northern Thailand” by John R. Davies Amazon.com; “The Hill Tribes of Thailand” (1989) Amazon.com; “Memoirs of a Karen Soldier in World War II: Saw Yankee Myint Oo” by Angelene Naw PhD Amazon.com; “Baptizing Burma: Religious Change in the Last Buddhist Kingdom” by Alexandra Kaloyanides Amazon.com; “Spaces of Solidarity: Karen Activism in the Thailand-Burma Borderlands” by Rachel Sharples Amazon.com

Karen Kin and Matrilineal Relationships

There is a strong matrilineal component — based on kinship with the mother or the female line — to Karen society. Nancy Pollock Khin wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “There is much scholarly controversy regarding the Karen kinship system, which is probably best characterized as a bilateral system with matrilineal descent with groups of matrilineally related persons participating in certain rituals for their ancestral spirit. The leader was the oldest living female of the line. Ancestral rituals taking place among both Sgaw and Pwo Karen matrilineages. Have been observed. [Source: Nancy Pollock Khin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

The Karen bilateral system of filiation does not result in a descent group, but a set of statuses for structuring relationships. Matrilineal descent, on the other hand, indicates a person's genealogical connection to his or her mother's relatives. A Karen man and woman who are directly related to each other through a pair of sisters, for example, should not marry because they are members of the same matrilineage, although if there is even one male in the descent chain they may marry.

Karen kinship terminology is overall quite similar among subgroups. A person equates his or her father's brother with his or her mother's brother. For grandparents and great-grandparents, male collaterals (maternal or paternal) of the same generation are equated, as are females. There are separate terms for generations, equating all children in each generation. An individual calls siblings only by birth-order terms, and may add a suffix to denote gender.

People distinguish their own children from their brothers' children and their sisters' children, whom they equate with the children of their cousins. Birth order is important, but is usually used only in the first ascending and descending generation.

Karen Marriage

Marriages are monogamous Young Karen men and women are relatively free to marry who they want as long as they get parental approval and don’t marry someone who is too closely related to them such as siblings, first cousins, and lineage mates. Among Pwo and Sgaw Karen there are rules against certain matrilineal and intergenerational marriages. Patrilateral parallel second cousins can marry, but matrilateral parallel cousins of any degree can not because the latter shares the same lineage or same female spirit. [Source: Nancy Pollock Khin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Courting tales place at weddings, funerals and festivals and in situations where people gather together such as during planting and harvesting. Proposals can be made directly from a man to a woman or through a go-between. Premarital sex is discouraged. About a fifth of all bridegrooms pay fines for breaking sex-before-marriage prohibitions.

The marriage ceremony involves rituals oriented towards the Lord of the Land and Water, marking the union of the new couple and the husband's incorporation into the bride's parents' household. The feasting and partying can last for three days. After the wedding the newlyweds move in with the bride’s family and the bride begins wearing new clothes: in many cases giving up the long white dress worn by single women and instead wearing the black embroidered blouse and red-and-black sarong worn be married women.

Divorce is discouraged and rarely occurs. In Thailand, about 5 percent of the marriages in the hills and 10 percent of the marriages in the lowlands end in divorce. Both the wife and the husband can initiate divorce proceeding which are usually granted after a payment has been made to the to person who was divorced. Adultery is regarded as a serious crime, sometimes resulting in the banishment of the guilty parties.

Karen Families

The normal domestic unit is the nuclear family, made up of husband, wife, and unmarried children. In the hills each nuclear family traditionally occupied either an apartment in a longhouse or a separate house in the village. Residence is usually in the village of the wife's family. Up to 30 percent of Karen marriages are between partners from different villages. In these cases, the groom moves to the house of the bride's father and eventually may establish a new household in that village. Postmarital residence depends as much on availability of agricultural land as customs regarding matrilineal ties, and family and village bonds. [Source: Nancy Pollock Khin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Property is generally divided into three shares, with equal parts going to the eldest and youngest children and slightly smaller shares to middle children. Inheritance customarily has taken before the death of the parents, to avoid disputes and the bad luck brought by personal property containing the dead person's k'la or spirit. The youngest child, preferably a girl, cares for the parents until their deaths and controls their property. Widows retain control of their property until remarriage.

Men tend to do heavy work such as plowing, slashing and burning, hunting, build houses, cutting timber and watering the paddy fields. Women weave, weed, harvest, carry water ad firewood, process crops, gather wild fruits and vegetables, and do household chores. Both men and women fish, cook, thresh and winnow grain and make baskets and mats.

Traditionally, Karen women have feared childbirth because of the pain involved and the potential for death. They often eat carefully prescribed diets, follow strict taboos, wear amulets and have magic spells cast on them to ensure a trouble-free birth. After a child is born, the mother sits next to a fire for three days while rituals are performed to protect her and her child.

When the child is one month old there is a naming ceremony. Children are recruited at an early age to work in the fields and help take car of siblings. If possible they attend government- or missionary-run schools. Older siblings are considered role models for younger family members. Younger children typically respect the discipline of older siblings and defer to them. Dress and hairstyles are considered a way for children to demonstrate this respect. Thus, within many Karen families, it is important for boys to keep their hair short, and older girls should cover their legs. Likewise, many parents feel that all children should cover their stomachs. [Source: Courtney Imran, Karen Culture, Des Moines Public Schools]

Karen ladies

Karen Society

Society is egalitarian, unstratified and organized along matrilineal lines with each family belonging to lineages, which also have a rank based on closeness to the common ancestor. There are no commoners and aristocrats. Status levels exist based on education, wealth and age, traditionally with elephant owners at the top. The young are expected to show respect to the elderly and wealth is determined by the number of cattle and elephants one possesses. [Source: Nancy Pollock Khin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

The four basic social residential units are the nuclear family, lineage segment, village and village complex, each with their own defined ritual, social and political functions. Nuclear families are usually linked with matrilineal descent or marriage, and may be organized around one or multiple lineages. Religion also plays a part in social organization. Lineage rites require the presence of all descendants of the matrilineal group regardless of which village they live in. Identity is attached to a matrilineal line, not a place.

Villages are led by a chief and a council of elders. Chieftainship is often hereditary position based on male lineal or collateral line (not directly related by descendants). The chief presides over secular and religious functions, arbitrates disputes and is chosen based on his personal influence in the community. Punishments are often in the form of sacrifices with meat given by the guilty party to the offended party. Property is divided relatively equally among all sons and daughters. To avoid disputes inheritance is ideally worked out before parents die.

Karen Villages and Houses

Karen villages tend be small, with around 20 or so households. Traditionally, the houses were clustered close together behind a stockade for defensive reasons. Upland and lowland Pwo Karen villages are often arranged with matrilineal kin living in houses together, a custom perhaps derived from the traditional Karen longhouse. In the old days, many villages had longhouses. Villages described in the 1830s contained three to six longhouses, each holding several families with a separate ladder for each. Sgaw Karen village names often reflect their pattern of settlement in valleys at the headwaters of streams. Settlement indicates the importance of the village as a community, as village sites were frequently moved but the village retained its name and identity. [Source: Nancy Pollock Khin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Houses have traditionally been made from bamboo, sometimes in combination with wood timbers. In the old days they often had thatched roofs and required reconstruction in a new location every few years. Karen dwellings vary depending on where they are built. Those built at lower elevation are made primarily of bamboo and wood timbers and have thatch roofs and are entirely rebuilt very couple years. Upper elevation houses are more substantial and last longer. They have wood posts and plank floors, sometimes rough-hewn teak, bamboo walls and roofs covered by grass thatch or real leaves. These have to be rethatched every year. Those than can afford them have corrugated metal roofs. In the Myanmar plains Karen housing usually follows lowland-Burmese style.

Karen village

In some Karen traditional houses, you will see bronze frog drums and buffalo horns. Bronze frog drums are a symbol of Karen heritage and buffalo horn is a musical instrument played in their leisure time. There are four rooms in the Karen traditional house. Fruits, betel nuts and rice are put out to dry on the open extension of the floor. Parents and brothers sleep in the front room. You can go to the kitchen through virgin's room. Clothing woven on a Karen traditional back strap loom is also seen there.

Many houses are raised above the ground so they don’t flood and have their own granary. Animals are often kept under the houses. A typical house is inhabited by five to seven family members. Longhouses in the 1920s accommodated 20 to 30 families. The traditional Kayah house is built on stilts and cattle and pigs are kept under it. There have traditionally been no window because it can get cold in Kayah State. For protection against severe weather roofing goes past the floor and nearly touches the ground. There are two fireplaces— one for the host and one for the guest to warm up when its cold and also to cook.

Karen Food

According to the Karen Organization of Minnesota: Meals are served in family groups sometimes including friends or neighbors. A typical Karen meal includes a large container of rice accompanied by smaller bowls of meat or fish, vegetables, chilies, fermented fish paste, and other foods and spices. Common vegetables consist of squash, bamboo, cucumbers, mushrooms, and eggplants. The Kayah usually have a meal in a big circular bamboo-lacquerware tray with legs. They like to drink an intoxicating brew they make themselves and drink from ugs usually made of bamboo.

A fish paste known as “nya u” in the Karen language and “ngape” in Burmese is a famous dish, flavoring and condiment among the Karen. The strong-tasting paste is made from fermented fish pounded into a fish paste and usually served with rice and vegetables for added flavor. Ngapi is also used as a condiment such as ngapi yay,an essential part of Karen cuisine, which includes runny ngapi, spices and boiled fresh vegetables.

Meals are often flavored with chilies and added spices like turmeric, ginger, cardamom, tamarind, lime juice, and garlic. Cultural Beliefs about Nutrition and Health: 1) People who are ill should have food that will make the body hot. 2) Papaya causes malaria. 3) People showing hepatitis symptoms should avoid yellow food. 4) Bitter and sour foods prevent health problems. [Source: Courtney Imran, Karen Culture, Des Moines Public Schools]

In a review of a Karen restaurant in Yangoon, Nay Thiha wrote: Frog curry is cooked without oil. The meat is mixed with chili and herbs. The major ingredient here is Acacia concinna leaves which give the curry sharp sour taste. The frog is fat and succulent. Imagine chicken but a lot more tender. The mistress says customers – locals and expats – often ask for frog meat, so they keep it on the menu. More conventional options like chicken and seafood are also available. A Karen feast will not be complete without Talapaw, a thick broth with veggie and meat. The soup is made of rice powder and a lot of greens including basil, pumpkin, bamboo shoots, etc. You can have it with meat or vegan, original or spicy. If you love hot food, try the spicy. They use fresh chili and lime to tingle your taste buds. One bowl is enough for three people. We had it with mussels. [Source: Myanmore, Nay Thiha, March 3, 2020

Omens in the Sun

Many insects have found a place in the diets of the Burmese, Karens, Chins, Kachins, Shans, Talaings and others. Distant (1892) and Bodenheimer (1951) reported that the larva of the cicadid, Platypleura insignis, is collected by the dexterous use of a long thorny branch inserted into a shaft sunk 60-90 centimeters into the ground. It is considered a great luxury by the Karens. scarabaeid, the larva of Oryctes rhinoceros, which breeds in dung heaps and is eaten fried, is "highly esteemed by the Karens."The larva of Xylotrupes gideon is also eaten.Other Coleoptera include larvae of various species that are found in cattle droppings and which are "eaten by many"; and various beetles attracted to light and collected with lanterns, then eaten or sold. [Source: www.food-insects.com ]

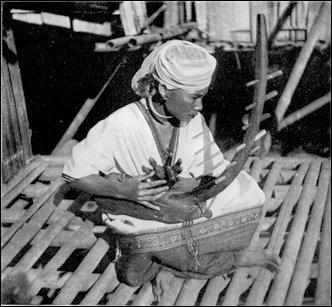

Karen Music, Culture, Folklore and Art

Vocal and instrumental music is performed at festivals, events and religious ceremonies. Karen love songs and ballads are particularly well known. In schools, songs are often used in teaching. Among Christians church singing is popular. Traditional musical instruments including the Phasi or bronze frog drum and buffalo horn. Bronze drums made by Shan craftsmen are valued as treasured possessions.

The don dance is a traditional Karen dance. "Don" means "in agreement". Originating among the Pwo Karen, who developed it as a way to reinforce community values, the dance is a series of uniform movements accompanied by music played from traditional Karen instruments. During the performance, a "Don Koh" leads the troupe of dancers. The sae klee dance or bamboo dance is performed during celebrations such as Christmas and New Year's. Performers, typically divided into two groups, with one group creating a platform by holding bamboo sticks in a checkered pattern and the other group dances on top of the platform. Dancers must be careful not to step into the platform's many holes.[Source: Wikipedia]

Karen weaving features embroidery and seed work embellishments. Karen make jewelry from silver, copper, and brass; ornaments of wool or other materials; beads; rattan or lacquered-thread bracelets; and traditionally earplugs of ivory or silver studded with gems. In the Thai hills, males are still tattooed for adornment. [Source: Nancy Pollock Khin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Folklore: See Karen Creation Myth Under Religion in the article; KAREN MINORITY factsanddetails.com and the Legend of Thandaung Under MON AND KAYIN (KAREN) STATES factsanddetails.com

Karen woman in traditional clothes sewing

Karen and Kayah Clothes

Karen have their own kind of textiles. Kayah women often wear clothes they make themselves with cotton on back strap looms handed down from mother to daughter. There is a great variety of Karen dress and tribe members can usually tell which village a person is from by the patterns on his or her clothes. Black Karen men wear black shirts with a red cummerbund or head scarf. The Pa-O wear colorful towels around the heads.

Karen women traditionally have worn horizontally-stripped, sarong-like tube skirts and loose black blouses embroidered with brightly colored wool. Karen men traditionally have worn bright-colored turbans, red-fringed shirts and sported tattoos with strange script chosen by shaman to ward off evil spirits. Kayah women wear basic but elegant black smock-like dresses which are draped over one shoulder and held in place by a long white sash. Kayah men wear no traditional costume. Some believe that the traditional costumes of men fell into disuse after they were ripped up by too much elephant riding.

The Karen make jewelry from silver, copper and brass. They wear bracelets made with beads, rattan and lacquered thread and used to wear ear plugs made of ivory and studded with precious stones. Paduang women (Paduang are regarded as a Kayah branch) have traditionally worn distinctive rings made from lacquered cotton cord around their legs. The first rings are tied below the knees of girls at the age of five. More and more chords are added as they grow older. By the time they are young women, the chords have reached a width of five or six inches and weigh four or five pounds. The leg rings are adjusted every day, but never removed, and according to legend they were introduced to keep women from running away from home. The custom of leg rings is a bit cruel and it is dying out. Very few Kayah women wear them any more.

Kayah men wear white headdresses and shirts with traditional jackets and trousers just past the knees. Silver daggers and stringed silver swords are carried on traditional occasions. Some Kayah women wear their hair in high knots wrapped with red headdresses. Their sleeveless blouses are normally black, covering only one shoulder. Red cloaks are worn over the blouses. Long white long shawls are tied around the waist with both ends hanging loose in front. They usually wear red or black longyis.

Shan and Kayah men’s traditional costumes are quite different from other groups because they wear loose trousers. Shan trousers are light brown, brown, terracotta or grey color while Kayah trousers are only black. Shan men tie their trousers like “longyi” Kayah men tie them pink band at the waist on their trousers. Bamar, Kachin, Mon, Shan, Kayah and Rakhine men wear a traditional jacket called a “teik -pon” over their “eingyi”. It is white, grey, black or terracotta in color.

Karen dance

Burman, Kayin, Chin, Kayah, Mon, Rakhine and Shan women’s “longyis” are nearly the same, made by cotton. A black waistband is stitched along the waist end. This waistband is folded in front to form a wide pleat, and then tucked behind the waistband to one side. Burman, Mon, Rakhine, Chin, Kayah, and Shan women’s” eingyis” are nearly the same, comprised of a form-fitting waist length blouse. Kayah women tie this traditional shawl on their “eingyi” embroidered with male and female royal birds called “Keinayee & Keinayah”. Kayin, Shan, Kachin, Chin women tie a lovely band on their head.

Karen Bronze Drums—an Ancient Animist Art Form

Dr. Richard M. Cooler wrote in “The Art and Culture of Burma”: “The use and manufacture of bronze drums is the oldest continuous art tradition in Southeast Asia. It began some time before the 6th century B.C. in northern Vietnam and later spread to other areas such as Burma, Thailand, Indonesia and China. The Karen adopted the use of bronze drums at some time prior to their 8th century migration from Yunnan into Burma where they settled and continue to live in the low mountains along the Burma - Thailand border. During a long period of adoption and transfer, the drum type was progressively altered from that found in northern Vietnam (Dong Son or Heger Type I) to produce a separate Karen type (Heger Type III). In 1904, Franz Heger developed a categorization for the four types of bronze drums found in Southeast Asia that is still in use today. [Source: “The Art and Culture of Burma,” Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Professor Emeritus Art History of Southeast Asia, Former Director, Center for Burma Studies =]

“The vibrating tympanum is made of bronze and is cast as a continuous piece with the cylinder. Distinguishing features of the Karen type include a less bulbous cylinder so that the cylinder profile is continuous rather than being divided into three distinct parts. Type III has a markedly protruding lip, unlike the earlier Dong Son drums. The decoration of the tympanum continues the tradition of the Dong Son drums in having a star shaped motif at its center with concentric circles of small, two-dimensional motifs extending to the outer perimeter. =

“In Burma the drums are known as frog drums (pha-si), after the images of frogs that invariably appear at four equidistant points around the circumference of the tympanum. A Karen innovation was the addition of three-dimensional figures to one side of the cylinder so that insects and animals, but never humans, are often represented descending the trunk of a stylized tree. The frogs on the tympanum vary from one to three and, when appearing in multiples, are stacked atop each other. The number of frogs in each stack on the tympanum usually corresponds to the number of figures on the cylinder such as elephants or snails. The numerous changes of motif in the two- and three-dimensional ornamentation of the drums have been used to establish a relative chronology for the development of the Karen drum type over approximately one thousand years.” =

Karen traditional musical instruments

Uses of Bronze Drums

Dr. Richard M. Cooler wrote in “The Art and Culture of Burma”: “Bronze drums were used among the Karen as a device to assure prosperity by inducing the spirits to bring rain, by taking the spirit of the dead into the after-fife and by assembling groups including the ancestor spirits for funerals, marriages and house-entering ceremonies. The drums were used to entice the spirits of the ancestors to attend important occasions and during some rituals the drums were the loci or seat of the spirit. [Source: “The Art and Culture of Burma,” Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Professor Emeritus Art History of Southeast Asia, Former Director, Center for Burma Studies =]

“It appears that the oldest use of the drums by the Karen was to accompany the protracted funeral rituals performed for important individuals. The drums were played during the various funeral events and then, among some groups, small bits of the drum were cut away and placed in the hand of the deceased to accompany the spirit into the afterlife. It appears that the drums were never used as containers for secondary burial because there is no instance where Type III drums have been unearthed or found with human remains inside. The drums are considered so potent and powerful that they would disrupt the daily activities of a household so when not in use, they were placed in the forest or in caves, away from human habitation. They were also kept in rice barns where when turned upside down they became containers for seed rice; a practice that was thought to improve the fertility of the rice. Also, since the drums are made of bronze, they helped to deter predations by scavengers such as rats or mice. =

“The drums were a form of currency that could be traded for slaves, goods or services and were often used in marriage exchanges. They were also a symbol of status, and no Karen could be considered wealthy without one. By the late nineteenth century, some important families owned as many as thirty. The failure to return a borrowed drum often led to internecine disputes among the Karen. =

“Although the drums were cast primarily for use by groups of non-Buddhist hill people, they were used by the Buddhist kings of Burma and Thailand as musical instruments to be played at court and as appropriate gifts to Buddhist temples and monasteries. The first known record of the Karen drum in Burma is found in an inscription of the Mon king Manuha at Thaton, dated A.D. 1056.. The word for drum in this inscription occurs in a list of musical instruments played at court and is the compound pham klo: pham is Mon while klo is Karen. The ritual use of Karen drums in lowland royal courts and monasteries continued during the centuries that followed and is an important instance of inversion of the direction in which cultural influences usually flow from the lowlands to the hills. =

Playing and Making Bronze Drums

Dr. Richard M. Cooler wrote in “The Art and Culture of Burma”: “When played, the drums were strung up by a cord to a tree limb or a house beam so that the tympanum hung at approximately a forty-five degree angle. The musician placed his big toe in the lower set of lugs to stabilize the drum while striking the tympanum with a padded mallet. Three different tones may be produced if the tympanum is struck at the center, edge, and midpoint. The cylinder was also struck but with long strips of stiff bamboo that produces a sound like a snare drum. The drums were not tuned to a single scale but had individualized sounds, hence they could be used effectively as a signal to summon a specific group to assemble. It is said that a good drum when struck could be heard for up to ten miles in the mountains. The drums were played continuously for long periods of time since the Karen believe that the tonal quality of a drum cannot be properly judged until it is played for several hours. [Source: “The Art and Culture of Burma,” Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Professor Emeritus Art History of Southeast Asia, Former Director, Center for Burma Studies =]

For the Karen, the bronze drums perform a vital service in inducing the spirits to bring the rains. When there is a drought, the Karens take the drums into the fields where they are played to make the frogs croak because the Karens believe that if the frogs croak, it is sign that rain will surely fall. Therefore, the drums are also known as "Karen Rain Drums" =

“The town of Nwe Daung, 15 kilometers south of Loikaw, capital of Kayah (formerly Karenni) State, is the only recorded casting site in Burma. Shan craftsmen made drums there for the Karens from approximately 1820 until the town burned in 1889. Karen drums were cast by the lost wax technique; a characteritic that sets them apart from the other bronze drum types that were made with moulds. A five metal formula was used to create the alloy consisting of copper, tin, zinc, silver and gold. Most of the material in the drums is tin and copper with only traces of silver and gold. The Karen made several attempts in the first quarter of the twentieth century to revive the casting of drums but none were successful. During the late 19th century, non-Karen hill people, attracted to the area by the prospect of work with British teak loggers, bought large numbers of Karen drums and transported them to Thailand and Laos. Consequently, their owners frequently incorrectly identify their drums as being indigenous to these countries. =

Karen Economy

Many Karens are active in business. Lowland Karen are involved in the Burmese economy. Hill Karens have traditionally traded cloth, forest products and domesticated animals for salt, rice and fish paste. In Thailand, many do wage labor. Some have set up small canteens that sell soft drink and beer to trekkers and make money from allowing tourists to take their picture. The Karen have largely shunned the drug trade. The Karens in the hills and in Thailand used to grow it. [Source: Nancy Pollock Khin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Karens are renowned for their elephant-handling skills and many work as mahouts for logging companies or tourist trek companies. Most of the mahouts in Myanmar and Thailand are Karen. Some Karen men still hunt wild pigs, deer, squirrels, lizards and deer with guns, crossbows, slingshots, snares and traps. Women and children collect frogs, mushrooms, paddy crabs, insects, ant larvae, honey, wild foods and medicinal plants. Fishing is done with poles, traps and baskets. Water buffalo are used in wet-land agriculture. Pigs and chickens used to be raised mainly for sacrifices but now they are mainly sold for cash to the Thais.

Weaving has traditionally been women’s work. Hill Karen mostly use belt looms while lowland Karens use Burmese fixed-frame looms. In the past they grew, spun, dried and wove all their own cloth. These days they still grow and spin some cotton but most buy threads at local markets. Among the items they make are clothing, blankets and bags decorated with patterns and symbols unique to each subgroup. Highland women also make baskets and mats, Men has traditionally made tools, machetes and weapons.

Karen Agriculture

The Karens have traditionally been subsistence slash-and-burn agriculturalists that grew mainly dry rice. They have traditionally burned and prepared their fields in March, planted before the summer monsoons and harvested in October, threshed in November, and stored in granaries. In recent years more and more Karens have switched to wet rice and pursued a subsistence- and market oriented stategy in which they produce enough food for survival and a cash crop. For many he annual ritual cycle is still associated with the longer slash-and-burn rice-growth cycle. [Source: Nancy Pollock Khin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993|]

The majority of Karens live in the lowlands rather than in the mountains. Karen farmers in the lowlands grow wet rice, tobacco, betel nut, and fruit such as bananas, durians and mangoes. Those who live in the hills raise dry rice, cabbage, vegetables, opium, tea, maize, legumes, yams, sweet potatoes, peppers, chiles and cotton. The land rights to slash-and-burn agricultural land varies widely but is mostly decided by village chiefs and elders. Overuse of slash-and-burn agricultural land is a problem. Irrigated land are often privately owned and can be inherited.

The mountain and hill Karen practice slash-and-burn agriculture and speak languages that lowland Burmese don't understand. The practice of slash-and-burn agriculture consists of burning the forests and then using the ashes from the burnt timber as fertilizer for the fields. The fertilizer lasts for only several years, never more than six, and at that time the Karen must pack and move everything to a new site where a different section of the forest is burned. A number of hillside groups practice slash-and-burn agriculture and periodically move through each other's hereditary territory to new lands. These people move back and forth across the Myanmar-Thai border with little regard for the national boundary. Slash-and-burn agriculture is not always easy as after the forest is burned, seeds must be planted and then rains must occur quickly and consistently until the plants are well established. If this does not happen, the plants wither and die or insects and animals will eat the seeds. It is not unusual for the Karen to be forced to plant four times in order to reap a single harvest.

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Land use and rights to swiddens (slash-and-burn land plots) vary depending on local politics, ecological stability, and population demands on resources. Usufructuary rights to swiddens and fallow swiddens are common. Traditionally each village had its accepted farming areas in which community members were free to use what they needed as long as they selected plots within swiddens designated by the village chief and elders. Today the need to remain on a site permanently in order to own the paddy fields for wet-rice cultivation has forced many hill Karen, particularly in Thailand, to give up swiddening or to overwork and thus lower the productivity of nearby swidden fields.

Environmental Issues That Affect the Karen

Seven dams have been proposed for the Salween River. The largest of these hydropower projects is the 7,100megawatt (MW) TaSang Dam on the Salween River, which is to be integrated into the Asian Development Bank’s Greater Mekong Sub-region Power Grid. A ground breaking ceremony for the Tasang Dam was held in March 2007, and China Gezhouba Group Co. (CGGC) started preliminary construction shortly after. [Source: Wikipedia]

Ka Hsaw Wa, Co-Founder and Executive Director of EarthRights International, is the Winner of the 1999 Goldman Environmental Prize, the 1999 Reebok Human Rights Award, the 2004 Sting and Trudie Styler Award for Human Rights and the Environment, the Conde Nast Environmental Award and the 2009 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Emergent Leadership. [Source: EarthRights International]

The article “Kawthoolei and Teak: Karen Forest Management on the Thai-Burmese Border” described how the “The Karen State has been heavily dependent on teak extraction to fund the Karen National Union struggle against the Burmese military junta. Raymond Bryant explores the social and economic structure of the Karen State and the way in which resource extraction was more than simply a source of revenue it was also an integral part of the assertion of Karen sovereignty..." [Source: Raymond Bryant, "Watershed" Vol.3 No.1 July - October 1997, June 3, 2003]

See Karen Environmental Activist Under ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES IN MYANMAR factsanddetails.com and Salween Dams under DAMS IN MYANMAR, THE SALWEEN RIVER AND THAILAND- AND INDIA-BACKED DAM factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: East and Southeast Asia”, edited by Paul Hockings (C.K. Hall & Company); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2022