PADAUNG

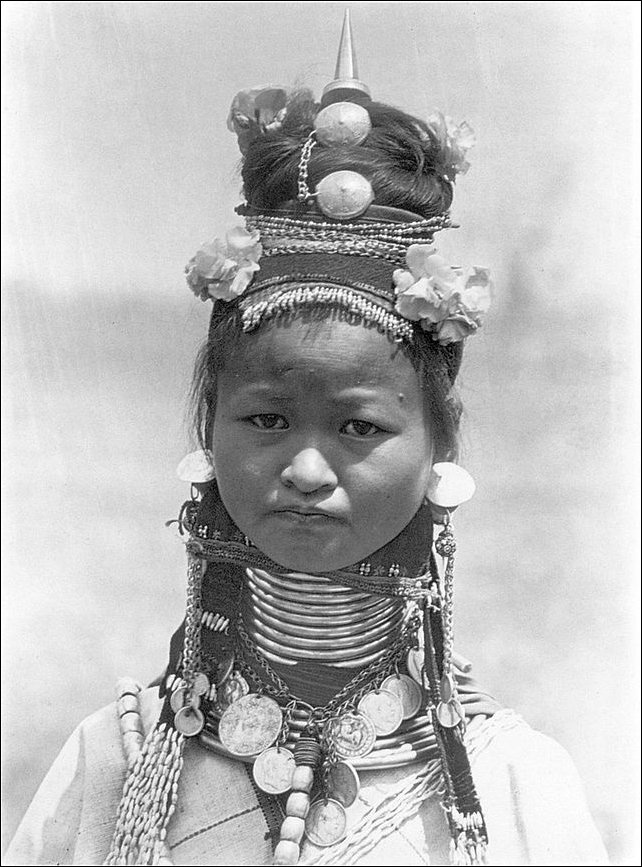

Paduang woman

The Padaung tribe is a subgroup of the larger Kayah tribe, which in turn is a subgroup of the Karenni which in turn is a subgroup of the Karen. The Padaung have no written language and are best known for its long-necked women. The tribe is named after the Padaung area, where most of them live. There are about 10,000 people in the tribe.

"Padaung" means "long neck" in the Shan anguage. Their homes and villages are found scattered in the area between the Kayah State, east of Taungoo and Southern Shan State. Some inhabit the plains in the basin of the Paunglaung River which are also part of the Kayah State east of Pyinmana.

The Padaung woman's traditional attire consists of a colorful, elegant turban with a short thick loose shift and leggings. Padaung women wear a short, dark-blue skirt edged with red with a loose white tunic also trimmed with red and a short blue jacket A turban-like headscarf is draped around their head. When working they wear short- sleeved smocks. Amit R. Paley wrote in the Washington Post, “The traditional wardrobe for Padaung women is a red, saronglike dress with a blue or magenta jacket and towellike head covering. Most distinctive are the dozens of rattan rings that circle their waists.” Men wear the basic Southeast Asian longji.

See Separate Articles KAREN MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION, KAYAH AND GROUPS factsanddetails.com ; KAREN LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ; TREKKING IN NORTHERN THAILAND, HILL TRIBES, ELEPHANTS AND LONG-NECKED WOMEN factsanddetails.com; KALAW, TAUNGGYI AND SOUTHWESTERN SHAN STATE AND KAYAH STATE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Commoditization of Culture In an Ethnic Community (Padaung): by Phone Myint Oo and Chayan Vaddhanaphuti Amazon.com; “Human Rights Issues in Tourism” by Atsuko Hashimoto, Elif Harkonen, et al. Amazon.com; “The Zoo of the Giraffe Women: A Journey Among the Kayan of Northern Thailand” by Martino Nicoletti Amazon.com; “Interconnected Worlds: Tourism in Southeast Asia” by K.C. Ho, P. Teo, T.C. Chang Amazon.com; “Lonely Planet Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos & Northern Thailand” by Greg Bloom, Austin Bush, et al. (20210 Amazon.com

Padaung Long Neck Women

The Padaung’s famous long-necked women wear brass coils — not rings — around their necks. A symbol of wealth, position and beauty, the coils can stretch their necks over a foot and weigh over 20 pounds According to the Guinness Book of Records, the world record for longest neck — 40 centimeters (15¾ inches) — belonged to a Padaung woman. The Ndebele in South Africa wear rings around their necks. Padaung means “long neck.”

The coils are made from brass and gold alloy. Because long necked women can't lean their head's back, they drink from straws. According to the British journalist J.G. Scott there voices sound "as if they were speaking from the bottom of a well.”

Padaung women might appear to have long necks but this is an optical illusion. As the coils are added they push the collar bone and ribs down, creating the appearance of a longer neck. Actually stretching the neck would result in paralysis and death. Removing the coils does not cause a woman's neck to collapse, although the muscles weaken.

Dr. John Keshishian, an American doctor, wondered what was happening anatomically to elongate the women's neck. Did the wearing of the rings create gaps between women’s vertebrae? And if this was the case was it dangerous? After X-raying several long-necked women in Rangoon he discovered that the neck was not expanding. Rather the chins of the women are pushed up and their collarbones are pushed downwards by the weight of the coils, causing the shoulders to slope.

Life of Padaung Long Neck Women

Kayah State, where the Paduang live

One woman told the New York Times, “It can be a bit boring and hot and it hurts when you first put it on...When you take off the brass you’re a little dizzy, and for one or two minutes you shouldn’t walk. You feel very light and you have a little headache, like you’ve been wearing a heavy backpack and you suddenly take it off.” The women also wear more brass loops around their legs which weigh up to 30 pounds. These loops force the women to waddle when they walk and sit straight legged.

Amit R. Paley wrote in the Washington Post, “Nae Naheng, 52, the matriarch of the family said the Padaung believe that women used to be angels in the past world, and that male hunters used rattan rings to catch them and bring them to Earth. Women are never supposed to remove the rings. Naheng said she even sleeps in them and only briefly takes off the rings in the shower. "Once I took them off when I was young, and I felt sick and very sad," she said. "If you do not wear the rings, your soul will get ill and you can die." [Source: Amit R. Paley, Washington Post, August 23, 2009]

” She is also adorned with jewelry and ornaments of which the most outstanding and unusual are the thick rings of bronze around her neck, worn right up to beneath her chin. The rings may appear cumbersome, but the Padaungs believe that beauty lies in a long neck, which is regarded as graceful as a swan's. The tradition of wearing bronze rings round the neck is slowly being discarded but there are still a few who continue to follow this age-old custom.

At about the age of 6, girls are allowed to choose whether or not to put on the rings. Wearers say that they are not uncomfortable, although their weight forces the shoulders down, making the neck look longer. According to the Sydney Morning Herald: “Young girls typically start wearing about 3 1/2 pounds of brass coil around their necks and keep adding weight until they have more than 11 pounds. They also wear coils on their legs. The women said the rings were painful when they were young but don't hurt now at all, and they said there are no health problems associated with wearing them. None of the Padaung I spoke to knew of any story or reason for wearing the rings. It was just a tradition, they said.

"Why do we wear the rings?" said Mamombee, 52, whose neck seemed particularly elongated. "We do it to put on a show for the foreigners and tourists!" I couldn't tell if she was joking. But Mamombee said she doesn't like to remove them except once every three years to clean herself. "I feel bad when I take out the rings," she said. "I look and feel ugly." [Sources: peoplesoftheworld.org; Sydney Morning Herald]

Padaung Long Neck Women Customs

No one is really sure how the custom evolved. The Kayan have no written language. Even elders don’t know. There are different theories as to how the custom originated. One suggests men put the rings on their women to deter slave traders. Another says the rings protected children from being killed by tigers, which tend to attack at the neck. Other say the custom began as a tribute to a dragon-mother progenitor.According to some people, Padaung women began wearing the coils to protect their necks against tiger attacks and continued wearing them after tigers were no longer a threat because Padaung men found the coils made the women more sexually desirable. Some say the custom have been dreamed up and perpetuated by tour guides. Most agree it is a form of adornment and may have been a way of saving and showing off family wealth. A Paduang woman told National Geographic, "Wearing brass ring around your neck makes you beautiful."

X-Ray of Paduang woman

In the old days it was said the women never took the coils off and that if they did the woman's neck would topple over and she would die from suffocation, a punishment sometimes meted out if the woman committed adultery. This seems to have be a myth. These days you often women not wearing their coils and looks as if their neck is no danger of suddenly collapsing. The belief that only girls born under a full moon on Wednesday can wear them also seems to be a myth.

Traditionally, at the age of five the first coils are placed around a young girl's neck by a medicine man who chose the date for this ritual by examining chicken bones. The first set of coils have a break at about the seventh rung above the clavicle to permit head mobility. As the girl grows taller, larger sets of coils replace the outgrown ones.” A little pillow on top of the loops cushions the chin. One 12-year-old girl told the New York Times she started wearing the coils when she was six and had 16 around her neck that cost $160,

The custom is dying out in traditional Pandaung villages in Myanmar, where people are so poor they prefer spend their hard earned money on rice rather than brass, but it is gaining new convert along the Thai border.

Padaung Long Neck Women and Tourism in Thailand

Several hundred Padaung live along the Thai-Myanmar border. Some fled to Burma to escape war. Most have come to Thailand to make money displaying themselves to gawking tourists. .In Nao Soi and Mae Hong Son Thailand, visitors pay $10 to be driven to a village where they can take photographs of long necked woman. In Huay Puu Kaeng the women are paid by operators ti live in a village on the Pai River that can only be reached by boat. Many foreigners don’t like practice and describe the villages as human zoos, but they visit them anyway.

Some places have become dependent on the women to bring tourist. The chairman of the Mae Hong Son chamber of commerce told the New York Times, “Long-necked Paduang are the star attraction to draw tourist to our province. All tourism-related businesses such as hotels, restaurants, and transportation services would be badly hit if they went away.

The practice has become so lucrative that Padaung women can support large families with their earnings. Many are collaring their daughters not out of respect for traditions but to make money in the future. Buying the coils is regarded as an investment. Parents of girls are often very happy and men like to marry long-necked women because of the money they will bring in.

Richard Lloyd Parry wrote in The Times: “As many as ten thousand tourists visit Nai Soi every year to see about 50 long-neck women and girls who pose for photographs and sell postcards, bracelets and souvenirs. They pay 250 baht (about £4) each; Mr Surachai admits to taking up to 150,000 baht a month (£2,400) from the entrance fee. Out of this the women and their families are supplied rice, chilli and cooking oil, and a monthly stipend of 1,500 baht (£24) per set of neck rings. [Source: Richard Lloyd Parry, The Times, April 8, 2008]

Sometimes the coils are placed on girls as young as two. One 8-year-old who refused to wear the coils told AP, “I prefer to be normal. No one can force me to wear the coils, but my friends think they are pretty with the rings around their necks and they also get paid.” In 2007, Lloyd wrote, two Kayan moved to a rival tourist attraction near Chiang Mai, where they were paid more than twice as well. When the news came out local business was outraged, the police were summoned and the Long Neck fugitives were brought back under arrest.

Paduang in Shan State in 1930

Life of the Padaung Long Neck Women and Tourism

The Padaung women live in special villages in reasonably nice huts. They are paid $20 to $60 a month from the tour company that brings tourists to see them, plus the money they get from tips and selling T-shirts, postcards and souvenirs. Otherwise they live relatively normal lives. In their free time some like to ride around on motorbikes and hunt dragonflies with poles and eat them.

One Padaung woman told AP, “It is not comfortable wearing these coils even while sleeping. But with them we can live in Thailand because they want us to stay this way....Our lives are better here. We prefer to live here rather than being sent back to Myanmar...We want food, clothes and other necessities. This is the only way we can earn money.”

In many cases the women simply go about their daily chores or play volleyball while tourist stare at them and ten ask them for tip or sell souvenirs or other items. Asked how it feels to be stared at one told the New York Times, “At first I felt frightened. I had never seen a Westerner before.” Then she said she got used it. “I’m glad when the tourist come because then we can make money.”

Everyday the women wash their coils with steel wool, and a mixture of lime, straw and tamarind bark. Many speak numerous language and capable of chatting with tourist in English, French, German, Japanese, Thai and even Hebrew.

Amit R. Paley wrote in the Washington Post, a village chief named “ Asung said they must wear the dress because of tradition, but he also spoke excitedly about its appeal to tourists and noted that half of the village's income of $30,000 a year comes from tourism. That night an Australian family was paying $15 to sleep in his hut. "He is very worried that visitors will stop coming," my guide, who served as my interpreter, told me as we left and headed to our own hut. As we walked across the village, Asung began broadcasting over loudspeakers: "This is a reminder that all women should wear traditional dress. Some foreigners just came to complain that some women were not wearing their costumes." (We quickly returned to explain to the tribal chief that I was asking questions, not complaining, but, unsurprisingly, he did not issue a correction over the village intercom.) [Source: Amit R. Paley, Washington Post, August 23, 2009 +++]

Paduang Long Necked Women Trek

Describing a trek that climaxed with a trip to a Padaung village Amit R. Paley wrote in the Washington Post, In the “morning I scrambled up on an elephant for an hour-long ride that left me sore all over (pachyderms, in case you were wondering, are not ergonomically designed) and a hour-long trip down the Ping River on a bamboo raft precariously held together by strips of rubber tire (I thought all was lost when the raft guide fell into the water after we bumped over some nasty rapids, but he recovered and got us to shore). [Source: Amit R. Paley, Washington Post, August 23, 2009 +++]

Paduang Dance

“Eventually we arrived at our main destination, the village of the long-necked women. It was off a dirt road, and a man at a booth in the front charged us 300 Thai baht (about $9) a person to enter. It didn't look like a village at all. We were ushered into a 50-square-yard collection of shacks where two dozen Padaung women sat and sewed or tried to sell their wares. There were no men in sight and only a handful of tourists during my two-hour visit. The women were as breathtaking as I imagined. Their heads seem to float ethereally over their bodies. In person they looked less like giraffes than swans, regal and elegant.” +++

See Separate Article TREKKING IN NORTHERN THAILAND, HILL TRIBES, ELEPHANTS AND LONG-NECKED WOMEN factsanddetails.com

Padaung Long Neck Women and Tourism in Myanmar

Loikow (five hours from Kalaw) is a medium-size town located on a lake in the Kayah State in Myanmar Most visitors come here to see the long-necked women of the Paduang tribe, a branch of the Karen tribe with only 7,000 members, most of whom live in villages within a 100 mile radius of Loikow.

Most tourist s see the long-necked women in Sompron village (about three miles south of the center of town), where ten long-necked women and girls live in small huts set up for them by a travel agency. They woman come out when visitors call on them. They don't speak any English so come prepared with some game or activity to keep them amused.

The visit to Sompron is a little strange and awkward. After allowing you take some pictures, the women speak up and say the only English words they know, "Five dollars please." Some people have compared the experience to a zoo trip. About three miles north of town three long-neck women live in a small village; and about ten miles down the road there is another village near Cabusera with four long-neck women and an Italian who speaks English and doesn't mind answering questions.

See Separate Article KALAW, TAUNGGYI AND SOUTHWESTERN SHAN STATE AND KAYAH STATE factsanddetails.com

Is Long-Necked Women Tourism Really That Bad?

National Geographic reported: “Some women are rejecting the rings because the tradition has trapped them in what critics call “human zoos” – mock villages where tourists buy tickets for a glimpse of these exotic women. Girls in these places do not attend school. If they move to a refugee camp, they get an education, but opportunities to earn money – or leave the country – are limited. Local businesses profit from the tourist traffic, and some Padaung women welcome the modest income. Is this economic empowerment, then, or exploitation? “It depends whether these women are coerced,” says National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Wade Davis. For Thailand’s Padaung women, the choice is very narrow. [Source: National Geographic, 2008]

Paduang women in Myanmar

Amit R. Paley wrote in the Washington Post, “Some trekking companies and human rights groups consider the Padaung villages, which stretch across northern Thailand, to be "human zoos" that exploit the women. There have even been reports that some of the Padaung are prisoners held captive in the villages by businessmen. "Disgraceful stuff!" Annette Kunigagon, the owner of Eagle House Eco-sensitive Tours, wrote in an e-mail. "We have been running culturally and environmentally friendly treks for 22 years and have never run treks to visit this tribal group as we would consider this exploitation as they have no rights. It is an easy trip to 'make' money out of, but this is not our interest!...PLEASE DO NOT SUPPORT THIS VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS!"[Source: Amit R. Paley, Washington Post, August 23, 2009 +++]

Describing the village, where the women live, Paley wrote: “There were no guards around, and it did not look to me as if anyone would physically stop the women from leaving. When I asked how they had arrived at this village, they said a man named U Dee, whom they referred to as "the middleman," first began bringing Padaung to the spot about three years ago. There are now about 50 families there, including some from a tribe known as "the long ears" because they stretch their lower earlobes by wearing enormous rings. Some families said they were paid about $45 a month, while others were given a sack of rice. One orphan girl said she was not paid at all. All the women and girls tried to raise extra money by selling trinkets or charging money to be photographed. +++

“The women are not allowed to leave the one-acre village. Groceries and other supplies are brought in by motorcycle every day. "We have to stay with the middleman," Mamombee said. "If I leave, he might call immigration." Does she want to escape? "I have no choice. If we leave, we will be arrested," she said. Their only option is to stay or pay U Dee money to be returned to Burma. But after pausing, she added: "I would much rather be here than in Burma." None of the Padaung I spoke with wished to return to Burma, but several expressed a desire for more freedom of movement. +++

"I want to go out and see things, see the market, see the people," said Maya, 11, who escaped from Burma three years ago. "But I cannot." Helen "Lee" Jayu, a Lisu shopkeeper from the same tribe as U Dee, said that all the Padaung are in Thailand under U Dee's patronage and that there are no problems as long as no one leaves the area. So is it unethical to visit the long-necked women? It is clearly true that money spent to visit them supports an artificial village from which they essentially cannot leave. On the other hand, many of them appeared to prefer living in virtual confinement as long as they are paid and safe. According to what they told me, their situation beats the alternative of living in a repressive country plagued by abject poverty and hunger. +++

Long Necked Women Speak Up About Their Situation

Amit R. Paley wrote in the Washington Post, “Did the Padaung women want to wear those enormous coils? "We're not allowed to take it off because of our tradition," said Malao, a 33-year-old who, like most Padaung women, has only one name. She takes off the rings once a year to clean the brass and her neck, but that's it. "If I take it off for a long time, it is uncomfortable. My head aches, and I feel like my neck can't support my head."[Source: Amit R. Paley, Washington Post, August 23, 2009 +++]

Joy Thaijun, 28, was wearing shorts and a T-shirt when I saw her. This annoyed my guide, who said that if the villagers stop wearing traditional costumes, tourists will stop coming to visit them. Embarrassed, Thaijun put on her costume and immediately tried to sell me some trinkets and handicrafts. After politely refusing, I asked her why she did not wear the costume. +++

"I am part of a new generation, and I do not like it. It is hot and uncomfortable," she said. But she noted that she might have to because the chief is considering forcing everyone to wear the costume. "If the chief orders us, we will do it." The chief of the village, a 52-year-old named Nanta Asung, told me that Thaijun was the only woman in the village who did not wear traditional dress and that her choice was unacceptable. "If you are Palaung, you have to wear the costume of the Palaung," he said while chopping pork for dinner. "This is a must. A must!" +++

“After a dinner of chicken curry, raw pork and a jungle delicacy identified as minced mole, I asked our hostess if she felt forced to wear the costume because of visiting foreigners. "I don't care about tourists," Naheng said. "This is our culture. Even if no tourists came, I would still wear it." +++

Paduang Woman Who Cast off Her Brass Coils

Rebellion is brewing in the so-called human zoos where the long-necked women live as virtual prisoners. Nick Meo wrote in The Times: “It began when Zember, 21, decided to cast off the brass rings. Contrary to what guides tell tourists, her head did not collapse on atrophied muscles; but mutiny by the most photographed woman in Nasoi Kayan Tayar village has provoked spectacular results. Bitter arguments exploded between young and old generations, the Thai businessmen who run the camps were furious and worried, and a new role model was born for a generation of disgruntled women. [Source: Nick Meo, The Times (London), November 6, 2006 ==]

“When they arrived a decade ago as refugees from Burmese army offensives ravaging their homeland, the Kayan people meekly accepted their role of being photographed by tourists. Their daughters, however, have grown up to question the humiliation of their tribe. Billboards showing the women’s necks are on roadsides all over the north. They advertise exotic sightseeing for Thai and foreign tourists alike in hill-country villages—in reality refugee camps that the women are forbidden from leaving—along the Burma border. ==

“Zember, whose hand darts constantly to her bare neck, admits that taking off the rings was a difficult decision. Business has fallen off at her souvenir stall and her family no longer has the payments that women receive for wearing the coils, a fraction of the profits made from selling entry tickets to tourists. She said: “I want to keep my people’s traditions but we are suffering because of these rings. We are denied education and the authorities will not let us go abroad, although some of us have been invited to leave for Finland and New Zealand.” Without work papers or citizenship, the Kayan have little say over what happens to them. They also face a plan to move their villages to a remote location on the border with Burma, where they believe they will be at risk from bandits. ==

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: East and Southeast Asia”, edited by Paul Hockings (C.K. Hall & Company); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2022