HILL TRIBE LIFE AND SOCIETY

Dong Festival Pole

Much of the day for ethnic minorities in southern China and Southeast Asia is taken up doing agricultural and household chores. A lot of time is also spent sitting around. People rarely leave their village except on market day when they go to the nearest town or large village. Protestant and Catholic missionaries introduced schools to many places.

Most villages are made up of members of clan or a group clans that can trace their relationship back to a common ancestor. Patrilineal descent defines kin groups which in turn forms the basis of village and community organization. People have traditionally been divided into two classes: commoners and aristocrats. Some hill tribes in China kept slaves until the late 1950s. There were two kinds of slaves — those that lived in the house and those that lived outside. Being an outside slave was preferable to being an inside one. Some large tribes, even today, live in feudal states ruled by hereditary princes.

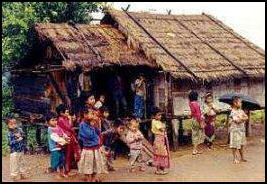

Hill tribe people usually are among the poorest people in their countries. Traditionally they have had a very low standard of living, short life spans and an infant mortality rate often ten or twenty times higher than the people in the lowlands. Many hill tribes live pretty much the same way they did 1000 years ago. Some seem to have decided to forsake the electricity, television and acquisition of consumer goods in order to retain their traditions. Others would like electricity, television and consumer goods but can't afford them. Others have them.

Most hill tribes live in regions where there are no large roads or cities, only footpaths and villages. Many hill tribe villages don't have electricity or running water. Most people get around on foot and carry goods on their backs. Even animal beast of burdens are regarded as a luxury. Many things are carried by women with a bags supported by a strap that wraps around the forehead.

Villages are headed by heredity chiefs (usually the head of the oldest clan) and/or a council of chiefs (made up chiefs of the other clans), sometimes with the help of a shaman (religious expert). Decisions are usually made with one, two or all three of these parties. Sometimes major decisions are made with input from all the male members of the village. Chiefs are often hereditary but are formally selected by a council of elders. They traditionally took tribute but had little say in how land was used and other matters. Council of elders had more say in these matters and settled disputes. Some chiefs are a combination headman, shaman and religious leader. They presides over all religious ceremonies. With some tribes, any time an animal is sacrificed or a wild animal is killed in the jungle a leg is given to the headman.

See Separate Articles: MINORITIES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AND SOUTH CHINA AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com ; LANGUAGE AND RELIGION OF MINORITIES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AND SOUTH CHINA factsanddetails.com HILL TRIBE ECONOMY, AGRICULTURE AND GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Book Chinese Minorities stanford.edu ; Chinese Government Law on Minorities china.org.cn ; Minority Rights minorityrights.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Ethnic China ethnic-china.com ;Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; China.org (government source) china.org.cn ; Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China Books: Ethnic Groups in China, Du Roufu and Vincent F. Yip, Science Press, Beijing, 1993; An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China, Olson, James, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1998; “China's Minority Nationalities,” Great Wall Books, Beijing, 1984

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Peoples of the Greater Mekong: the Ethnic Minorities” by Jim Goodman and Jaffee Yeow Fei Yee Amazon.com ; “Mon-Khmer Peoples of the Mekong Region” by Ronald D.renard and Dr. Anchalee Singhanetra-Renard Amazon.com; “Yunnan–Burma–Bengal Corridor Geographies” by Dan Smyer Yü and Karin Dean Amazon.com; Yunnan: “The Yunnan Ethnic Groups and Their Cultures” by Yunnan University International Exchange Series Amazon.com; “Ways of Being Ethnic in Southwest China” by Stevan Harrell Amazon.com; Myanmar: “Mandalay to Momien: A Narrative of the two Expeditions to Western China of 1868 and 1875, Under Colonel Edward B. Sladen and Colonel Horace Browne” Amazon.com ; “Frontier Ethnic Minorities and the Making of the Modern Union of Myanmar: The Origin of State-Building and Ethnonationalism” by Zhu Xianghu Amazon.com; Laos: “Minority Cultures of Laos: Kammu, Lua', Lahu, Hmong, and Iu-Mien” by Judy Lewis (1992) Amazon.com; “Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage” by Yves Goudineau Amazon.com; Thailand: “Minority Groups in Thailand” by Joann L. Schrock (1970) Amazon.com; “Ethnic groups in Thailand” (2006) Amazon.com; Hill Tribes: “Hill Tribes: Lonely Planet Phrasebook” by David Bradley (2008) Amazon.com; “Lonely Planet Hill Tribes Phrasebook & Dictionary” by David Bradley , Christopher Court, et al. (2019) Amazon.com; “The Hill Tribes of Northern Thailand” by John R. Davies Amazon.com; “Lao Hill Tribes: Traditions and Patterns of Existence” by Stephen Mansfield Amazon.com; Clothes and Costumes: “China's Minority Costumes” by Xing Li Amazon.com; “Costumes of the Minority Peoples of China” (1981) by Fei Xiatong Amazon.com; “Costumes of the Minority Peoples of China” (1982) by Central Academy of Ethnololgy Amazon.com “Costumes of the Minority Peoples of China” Amazon.com; “Headdresses of Chinese Minority National” by Xu Yixi Amazon.com; Culture, Music, Sports “Folk Poems from China's Minorities” by Rewi Alley Amazon.com; “Festivals of China's Ethnic Minorities” by Xing Li Amazon.com;“The Sports of China's Ethnic Minority Groups -Ethnic Cultures of China” by Zhang Tao Amazon.com “The Music of China's Ethnic Minorities” by Li Yongxiang Amazon.com; “Dances of the Chinese Minorities” by Li Beida Amazon.com

Customs of Minorities in South China and Southeast Asia

Almost every aspect of tribal life is governed by a social code which often combines poetry, mythology and tradition with morality and tribal law. Rural societies like those of ethnic minorities in China are relatively self sufficient. They grow there own food. Their political and social units are the tribe and the village. Elders and leaders wield much authority.

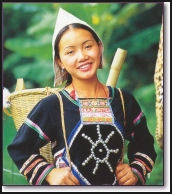

Jino girl

Many hill tribes are suspicious or shy around foreigners, and as a result they sometimes seem unfriendly and even a little hostile. Most foreigners visit hill tribes villages that have a steady stream of tourists coming to visit them. As is true with many Asian people, hill tribe members will do anything they can to save face and make foreign visitors happy even if it means misleading them. Instead of telling you the unpleasant truth they would rather tell you what you want to hear. American soldiers in the Vietnam War who asked tribal people if crossing a storm-swelled river was possible were told it would be easy. Only after they were swept down the river and came within an inch of losing their life did they realize the truth.

Hill Tribe etiquette for tourists. 1) Many hill tribes fear photography, believing that it steals the soul. Don’t photograph anyone or anything, especially things linked to spirits and religion, without permission first. 2) Show respect towards religious objects and structures. Don’t touch anything or enter or walk through any religious structure unless you are sure it is okay. If in doubt ask. 3) Don’t interfere in rituals in any way. 4) Don’t enter a village house without permission or an invitation. 5) Error on the side of restraint when giving gifts. Gifts of medicine may undermine confidence in traditional medicines. Gifts of clothes may encourage minorities to abandon their traditional clothes. 6) Don't sit on the entrance of village homes.

Holidays and Festivals

Many ethnic groups in Southeast Asia and Southern Chinese have colorful festivals, which take place throughout the year on dates usually set according to the lunar calender. Some tribes only wear their traditional costumes during these events. The festivals are often connected with ensuring a good planting season and a good harvest. Ceremonies are held to honor ancestors and spirits and invoke their aid.

Dai water festival

Festivals often feature lots of feasting, drinking, dancing and singing. The featured events are often courtship rituals and games between teenage boys and girls. Among the activities that are held are bullfights, drumming, horse racing, pipe playing, comic opera, singing contests, animals fights and huge courtship dances. Some festivals draw 50,000 people or more.

Wrist-tying is a custom performed by many hill tribes to keep an individual's 32 to 64 souls (depending on the tribe) within the body and ward off evil spirits. For couples at weddings tying cotton strings around one's wrists is the equivalent of exchanging rings. Some tribes place brass rings around the wrists as a welcoming gesture to new initiates. Even elephants are rewarded with wrist-tying ceremonies for working particularly hard.

Hair is considered by some hill tribes to be a favorite hiding place for evil spirits, and a rite of passage into adulthood for both boys and girls is getting a haircut.

Families, Women and Children

Often the youngest son is expected to live with his parents and take care of them in old age. In return he inherits the family’s property. Women often receive a dowry but do not inherit unless they have no brothers.

Men tend to do heavy work such as plowing, slashing and burning, hunting and watering the paddy fields. Women are known as being hard workers. They do weeding, harvesting, carrying and processing crops, gathering wild fruits and vegetables, cooking and household chores.

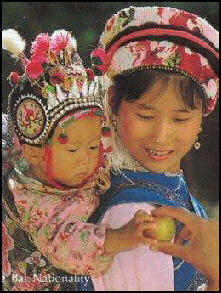

Bai mother and baby

In some tribes, pregnant women are not supposed to enter the house of tribe members from different clans through the front door of because of worries that the action will cause great misfortune. Using the backdoor is alright. The taboo is based on the on the belief that sickness results when evil spirits lure the soul from the body, which can only be taken through the front door. Pregnant women are sometimes viewed as polluted and potential carriers of evil spirits.

Among some tribes, pregnant women go into the forest to give birth. During the delivery the woman clutches a special wooden staff, and often gives birth while standing up. After the birth the mother and child are not allowed to enter their house for ten days, and then they must enter through the back door.

Members of some ethnic minorities go out of their way to avoid complimenting children because parents think that flattery attracts evil spirits. Others shave the heads of young boys, leaving a patch of long hair at the top to trick evil spirits into confusing the boy for a girl, which evil spirits usually don't bother, many believe, because they are not considered worth the trouble to harm.

Minority parents tend to be very gentle with their young children, seldom beating them, and giving them a fair amount of freedom to do what they want. When children reach the age of 12 or 13 they are expected to help out with chores. Boys help with herding; girls help in the gardens.

Marriage and Dating Among South Chinese and Southeast Asian Minorities

In some groups, arranged marriages are common. In other groups, love matches with approval from parents predominate. Some polygamy and polyandry is practiced. Most couples have traditionally gotten married when they are in their mid- to late-teens. In some cases marriages are arranged when children are five or six and formalized when they were 12 or 13 after a bride price was paid. Divorce and remarriage are often easy to arrange. Divorce is generally uncommon but when it does occur the bride usually has to pay back the bride price.

There are generally no restrictions on partners as long as they are from outside the patrilineal clan. There is sometimes a preference for marriages between a boy and his mother’s brother’s daughter or the offspring of the father's sister and mothers' brother. Among most ethnic minorities, monogamy is valued. Some groups value virgin brides and expect them to adopt the role of shy maidens when they are about to get married.

Couples usually live with or near the bride's family, and sometimes the groom's, until the inherit some property of the own. Brides often remain with her family until their first child is born. Among some tribes, if a husband dies his eldest brother usually has first dibs on the widow. If he doesn't want her, the widow's family is required to return some of the bride-price.

Young people in many groups sing to each other and flirt at festivals (See Music Below). Some groups encourage young couples to gets engaged in the early teens, enjoy conjugal visits and get married a year or so later. Sometimes young males and females are permitted to enjoy a "golden period of life" in which premarital sex is allowed and even encouraged. In some tribes young women signaled their interest in a young man by tossing him a silk ball. If he was interested they dated and later became engaged to marry. For some tribes the word "kiss" means "smell."

Mosuo love bath

Weddings and "Bride Kidnapping"

The weddings of ethnic minorities are often quite elaborate. There is often a wrist-tying ceremony, with the tying of cotton strings around their wrists being the equivalent of exchanging rings. Sometimes after the wedding ceremony women form a procession and carry the brides' weaving equipment and pots and pans to her husband's house.

If a couple decides to marry the family of the groom has to give the bride's family a bride price, a ritual payment in silver and buffalo, cattle, horses, or other animals that usually amounts to between a thousand and two thousand dollars. The amount is often determined by the number of relatives the bride has. In some cases in return, the bride’s family gives a gift to the son, often a spear, knife or sword, and preferably a gun worth half the value of the bride price. Sometimes the bride prices are quite high and the groom’s family can not pay it. When this occurs the groom is are required to do a bride service to the bride’s family. This means he works for the bride’s family, effectively is a servant, for a period of a year or more.

Ceremonial bride kidnaping was practiced among some groups and maybe still is. It took two forms: 1) wife stealing, the most popular form, in which the stealing is staged and both families consent to the marriage; 2) wife snatching, in which a man abducts a girl who refuses his love and marries her. Wife stealing was sometimes done to get out of paying the bride price.

Some tribes practiced bride kidnaping in which a "crying and whimpering" bride was kidnapped from her hut by the groom's friends or family. The bride was often carried away on horseback and was expected to cry for help, with her family giving chase in half-hearted manner. Most of the time, but not always, the bride knew the abduction was coming and usually it is arranged by friends of a boy she likes. Sometimes the groom’s family and friends were “attacked” when they tried to snatch the bride or afterwards. After a short “fight,” the bride’s family invited the groom’s family for a big feast. Later the groom's family visited the family of the bride to discuss the bride price.

Villages and Homes of Southeast Asian and South China Minorities

Many groups have traditionally lived in villages clustered together in the same general area. A typical village has 40 or so households with large villages having 100 or more. Villages are usually established along rivers or streams or near some other water supply. Having water for irrigation is an important consideration for choosing a village site.

Lahu house

Most villages are comprised of closely spaced dwellings, surrounded by vegetable gardens and orchards, with fields for grains and staple crops further away. Some tribes live in villages set at the foot of mountains on small plains. Their villages are often made up families related along patrilineal lines, sometimes with some other ethnic groups living there. As a rule the highest and more remote villages are the poorest ones.

Some ethnic minorities live in two-story bamboo houses with an area for storage and keeping animals in the bottom floor and living quarters with a fireplace in the middle of the main room on the second story. These houses are raised in a couple of days because the entire community pitches in to help with the construction.

Traditional one-story houses built on the ground have a grass roof, dirt floor and no windows. For some tribes, such a house is built so that the owner can see a distant mountain from the front door. After the site for a house is chosen one grain of rice is laid down for each member of the family and left over night. If the rice grains move it is assumed that spirits moved them and a new site is chosen.

Houses have few furnishings. People sleep on the floor or on bamboo beds or wooden platforms near the central fire pit. Food is cooked over an open fire pit or primitive stove made from bricks.

Many ethnic minorities live in houses that are built above the ground on stilts — to prevent the house from being flooded during the wet season — and have a thatched roof — cool in hot weather and warm in cool weather. Chicken and pigs are kept below the house, and a fenced garden surrounds the house. A typical house is 10-by-10 meters and two to three meters above the ground and has wooden and bamboo supports, walls and floors are made of woven bamboo and a steep-pitched thatched roof supported by bamboo rafters. The house is usually divided into an inner bedroom and outer living room with a fireplace that serves as a kitchen. Those that can afford them have planked floors and tile roofs.

In the 1960s it cost about $35 to build such a house. This price included timber stilts and beams, bamboo poles for the walls, bamboo mats for floors, labor, two pigs for a feast and a dog and two chickens for a sacrifice. Gathering the materials from the forest and preparing them took about three days; building the house took only a day. The hardest task was setting the timber stilts and building the frame. The construction of the fireplace (a wooden frame filled with sand) was "entrusted only to older men."

Food in Hill Tribe Areas

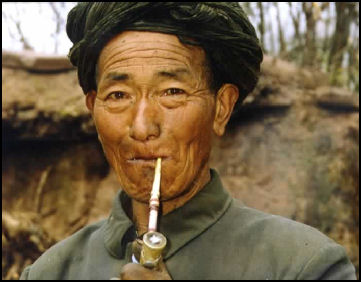

Yi man smoking Rice is the diet staple for many ethnic minorities in southern China and Southeast Asia. Sometimes it is paddy grown in lowland areas or terraces. Sometimes is a dry highland variety. It is usually ground into flour with wooden mallets and consumed as cakes or rice porridge. The diet may be supplemented with bread made from corn. A typical dish is pumpkin vines, stir fried with fish sauce, lemon grass and chilies. Many hill tribes eat dog. For dinner blood soup and roast lizard are sometimes eaten.

Chen Xiaoming (1990)(The Research Institute of Insect Resources) noted that there are many edible insects in Yunnan Province and that many minority nationalities use them as food and for medicinal purposes. Among the insects often eaten are a species of ant; locusts of the genera Oxya and Locusta; pupae of the silkworm, Bombyx mori; the termite, Coptotermes formosanus (Rhinotermitidae); larvae and pupae of five species of bees and wasps among the Apidae, Vespidae and Scoliidae; the moth larva, Hepialus armoricanus (Hepialidae); the bug Tessaratoma papillosa (Pentatomidae); and the weevil larva, Cyrtotruchelus longimanus (Curculionidae). [Source: “Human Use of Insects as a Food Resource”, Professor Gene R. De Foliart (1925-2013), Department of Entomology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002 ==]

In addition to studies on the folk edible insects of Yunnan, there is a study of Macrotermes barnyi as a health food. The queen termites are steeped in alcohol as a beverage rich in vitamins A and C among other micronutrients of benefit to health. A study that will not sound too appealing to many Westerners is on the presumed health benefits of Chongcha, a special tea made from the feces of Hydrillodes morosa (a noctuid moth larva) and Aglossa dimidiata (a pyralid moth larva). The former eats mainly the leaves of Platycarya stobilacea, the latter the leaves of Malus seiboldii. Chongcha is black in color, freshly fragrant, and has been used for a long time in the mountain areas of Guangxi, Fujian and Guizhou by the Zhuang, Dong and Miao nationalities. It is taken to prevent heat stroke, counteract various poisons, and to aid digestion, as well as being considered helpful in alleviating cases of diarrhea, nosebleed and bleeding hemorroids. Whatever the extent of its preventive or curative benefits, Chongcha apparently serves as a good “cooling beverage" having a higher nutritive value than regular tea. ==

Drinking, Smoking and Opium in Hill Tribe Areas

Some tribes consume homemade rice wine fermented in a large earthen jar and sucked from the jar through long bamboo straws to avoid swallowing mashed rice husks. Corn and rice wine are distilled into a powerful moonshine whose taste has been compared to white wine that has turned to vinegar. Men enjoy swapping animal stories over homemade rice wine. Elders discuss important issues while they drink rice wine through long straws. Generally, the more jugs of wine consumed, the more serious the problem is.

Both men and women hill tribe members smoke pipes, and it is not unusual for hill tribe children to start smoking at the age of four. Harsh dark homegrown tobacco is often smoked in corncob style-pipes with long stems made of silver, wood and buffalo horn. Cigarettes are considered a luxury out of reach to many people.

The bong — a water pipe made from a one-and-a-half- to three-foot-long tube of bamboo — was invented by hill tribes region in Southeast Asia and became popular with dope smokers in the United States the 1960s. The ethnic minorities that have traditionally used bongs mostly use them to smoke tobacco.

Many groups have traditionally raised opium. In addition to its use as a recreational drug, opium is used as a medicine, and is sometimes an important part of rituals. Hill tribe women tend to stay away from opium, while the men smoke too much of it, often smoking opium while they work or instead of working. Many hill tribe men who are addicted to opium don't live past 50.

Hill tribes in southern China began growing opium centuries ago as a source of medicines and way to earn money to pay taxes imposed by the Han Chinese. Over time it became a product they traded with lowland people. It has traditionally been regarded as acceptable for elderly people to smoke opium and pass away the end of their life in peaceful euphoria but was considered disgraceful for young people to become addicted. National Geographic recounted a story about a Miao man who ordered his son to stop smoking. The young man tried and failed. The father then told him to kill himself. He did.

See Opium Farming Under HILL TRIBE ECONOMY, AGRICULTURE AND GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com; See Separate Articles: OPIUM, MORPHINE AND HEROIN AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com; OPIUM, MORPHINE AND HEROIN USE factsanddetails.com OPIUM, MORPHINE AND HEROIN ADDICTION factsanddetails.com OPIUM CULTIVATION, HEROIN PRODUCTION AND THE OPIUM AND HEROIN TRADE factsanddetails.com

Health in Hill Tribe Areas

Miao transport

Traditionally ethnic minorities have had short life spans and an infant mortality rate that were often ten or twenty times higher than the people in the lowlands. They suffer from a number of illnesses and often lack access to modern health care. Cooking is often done over an open fire and the smoke causes a number of respiratory problems. Modern medicine is used where its available. Protestant and Catholic missionaries introduced modern medicines. Aid groups working with hill tribes hope they can improve the economic and health standards of the hill tribes without jeopardizing their unique way of life.

Minorities have traditionally believed that illnesses were caused by the possession of evil spirits or the disappearance of the soul from the body and were treated by shaman who use medicinal herbs, songs, chants, opium paste, camphor, deer antlers, bloodletting, heat application and exorcisms. In Kachin (Jingpo) areas of Myanmar heat suction is used to get rid of malaria. The Miao believe that epileptic seizures are caused by spirits called dabs and diseases are caused by "fugitive souls and cured by jugulated chickens." One epileptic Miao girl in the United States suffered from irreversible brain damage when her parents didn't give her medication that her American doctors prescribed. Many hill tribes believe that physical deformities such as withered arms and club feet are punishments for misdeed performed by ancestors. Some believe that surgery maims the body and makes it difficult for a person to be reincarnated.

Traditional healers often orient their treatments towards bringing back the soul from the body which has been lured away by evil spirits. Some groups examine the gall bladders of chickens for omens to help heal someone who is sick. Hmong (Miao) healers mix rice and corn liquor with herbs and folk medicine and offer it to chanting participants to thank the spirits for healing a sick baby, a shaman; go into frenzied trances to make deals with evil spirits in the clouds, at the bottom of a pond, in China to exorcise evil spirits from a house. Deals with the spirits are usually sealed with a pig or cow sacrifice from a rich customer and chicken sacrifice from poor one. [Source: W.E. Garret, National Geographic, January 1974]

Book: “The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down” by Anne Fadiman (Farrar, Straus & Giroux).

Clothes of Southeast Asian and South Chinese Minorities

Hill tribes are famous for their colorful clothes. Dress is an important means of distinguishing one tribe from another and tribe names often refer to their preferred colors. Each tribe has distinctive costume and women usually wear the most interesting outfits and headdresses. There is a great variety of dress within the tribes, and tribe members can usually tell which village a person is from by the patterns on his or her clothes, turban or headdress. Some tribes wear their traditional costumes all the time. Others only wear them during important festivals or events such as weddings and funerals. Yet others throw them on when tourists show up.

Nu woman making clothes

Both men and women wear skirts or sarongs. Many hill tribe women wear a heavy series of leggings and bracelets. Men generally they don't wear as colorful clothing as the women. They often wear black trousers, black jackets and colored sashes. Sometimes they wear turbans or skullcaps.

Unmarried women usually have different costumes than married ones. This custom has a practical side by informing potential suitors which women they can go after and which they can’t. Many hill tribe women wear black jackets with plain or brightly striped sleeves; black skirts and black trousers, with long, colored apron-like panels and wide sashes; and gaiters that extend from the ankle to the knee.

Each tribe has a distinctive head dress. Some wear a close-fitting hat, decorated with silver coins, beads, woolen pom poms and fringe. Sometimes the hats are kept in place with a chain under the neck. Women sometimes wear large silver rings, necklaces or chains around their necks with a silver linked belt over the sashes and jackets.

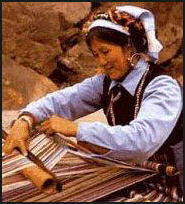

Many hill tribe women spend much of their time weaving colorful cloth which they wear themselves or sell to tourists. Many tribes have their own decorative designs and weaving techniques. The chok khit technique of the Lao Khrng, for example. employs discontinuous weaving and bright reds and greens and shades of black. Common design motifs include trees, flowers and animals that represent virtue.

Miao women are famous for their embroidery. Often a woman's ability to attract a good husband is determined by how well she can sew. Because Miao women don't use sewing machines, pins or patterns their stitches are virtually invisible.

The Lua make their own cotton cloth. First they remove the seeds from the cotton with a machine consisting of hand-cranked rollers. Then, the fluffy balls of cotton are turned into thread with a hand-turned spinning wheel. After the thread is sorted, dyed and washed it is made into cloth with a bamboo belt loom with foot-operated bamboo pedals, a hand-operated wooden carding system and poles for the yarn.

Jewelry, Silver and Wealth

Miao jewelry

Silver is the traditional symbol of wealth for many hill tribes. Women, and to a lesser extent men, wear silver necklaces, headdress ornaments and other kinds of jewelry, which are often bought with money sent by relatives living abroad, earned from selling opium to heroin makers, or selling silver jewelry and traditional cotton clothes to tourist shops.

Silver also serves as banking system. Families store their wealth in women's jewelry. The rich sometimes keep their wealth in silver bars, which are buried for safe keeping. Silver bars used in opium transactions are sometimes referred to as "Meo money." Attractive girls who earn large sums of money for their families as bride prices are sometimes referred to as three or four bar women.

Leonard Yiu, a collector of tribal costumes and jewelry, told the The Star (Malaysia), that old ethnic costumes and jewellery are precious because they are hard to come by today. In addition, the designs are incredibly intricate and the workmanship surpasses anything that can be found today — and, being custom and handmade, they’re all unique designs.”Nowadays the textiles and costumes are not as intricate because people have lost the patience and skills needed. Everything now is machine made. In the old days every girl was taught to sew from a young age and some attained very high status in their society solely because of their artistry. They were very accomplished artists in their community, even revered, he said. According to him, most tribal people have a lot of pride in their heritage and although they don’t mind showing him their collections, it is something they will not part with, even though they are poor.

See Miao Silver Adornments and Miao Silver Hats Under MIAO CULTURE, FOLKLORE, MUSIC AND CLOTHES factsanddetails.com and Silver Under DONG CULTURE: CLOTHES, SINGING AND ARCHITECTURE factsanddetails.com

Music, Art and Culture and Literature

Cloth making and weaving are arguably the most developed art forms. Traditional motifs include dancing shaman, mountains, strange, and multicolored animals. Huge courtship dances and comic operas are featured events at festivals. Yunnan government television broadcasts the news and special music and dance programs in the Yi language. People like to play checkers and other games and sit around smoking angel-haired tobacco from bongs. Cock fighting is popular among many groups. Bullfights, horse racing, and animals fights are featured events at festivals.

Literature exists in the form of poetry, folktales, legends, ballads, oral histories about chiefs or heroes or creation stories passed down from generation to generation. Poetry is sung and improvised. Famous folk tales may be based on tribal stories or traditional Hindu stories. Customs and traditions of most hill tribes have been passed down over the centuries in their oral literature and history. Hill tribes do not have a sense of history as we know it, and often myth and fact are intertwined. Many of their creation myths have a flood story.

Zhuang festival drum

According to one tribe’s creation myth, "Faam Kah and his sister Faan Tah created the world. Fam Tah created a huge earth with room for many people, but Faam Kah was lazy and made the sky too small, so his sister had to take her needle and sew the land into hills and mountains to make it fit. Soon there came a great flood and Faam Tah and Faam Kah were only saved by floating on the top of a mountain in a hollowed out gourd. "Faam Kah and Faam Tah later decided to marry, and after a three year pregnancy Faam Tah gave birth to a pumpkin. They hurled the pumpkin against the mountain and when it burst its seeds scattered. The few seeds that fell on the mountains became the hill tribe peoples; the many that fell on the valleys became the lowland peoples — greater in number but lower in quality." [Source: "Hands of the Hills" by Margaret Campbell, Nakorn Pongoi and Cusak Voraphitak, Media Transasia]

Many groups like to sing, socialize by exchanging songs and sing at festivals and events such as weddings. There are often specific songs for specific occasions: feasting, flirting, working, relaxing and entertaining guests. Songs have been also played a key role in passing down histories and folk tales from one generation to the next. Love songs are popular among young people. “Mountain songs” are often sung for courtship purposes. They are often accompanied by circular dances that involved the exchange of songs between males and females. The songs often recall myths and historical events and are used to woo lovers.

Hill tribe musical instruments include bamboo lutes, bamboo reed pipes, jew's harps, long drums, gongs and cymbals. The mouth harp has traditionally been plaid by women to serenade their lovers. In some places men play flutes for the same purpose. Drumming, pipe playing, and singing contests, are featured events at festivals. The best music is often experienced at New Year festivals. Boys in the Khmer-Loeu hill tribe entertain guests before dinner by playing a musical instrument made from strings pegged to a piece of bamboo. A gourd, which is attached to the instrument and rests against the musician's chest, amplifies the sound.

See Singing Under DONG CULTURE: CLOTHES, SINGING AND ARCHITECTURE factsanddetails.com and MIAO CULTURE, FOLKLORE, MUSIC AND CLOTHES factsanddetails.com

Bronze Drums

Bronze drums are something that ethnic groups of China share with the ethnic groups of Southeast Asia. Symbolizing wealth, traditional, cultural bonding and power, they have been prized by numerous ethnic groups in southern China and Southeast Asia for a long time. The oldest ones—belonging to the ancient Baipu people of the mid-Yunnan area—date to 2700 B.C. in the Spring and Autumn Period. The Kingdom of Dian, established near the present city of Kunming more than 2,000 years ago, was famous for its bronze drums. Today, they continue to be used by many ethnic minorities, including the Miao, Yao, Zhuang, Dong, Buyi, Shui, Gelao and Wa. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

At present, the Chinese cultural relics protection institutions have a collection of over 1,500 bronze drums. Guangxi alone has unearthed more than 560 such drums. One bronze drum unearthed in Beiliu is the largest of its kind, with a diameter of 165 centimeters. It has been hailed as the "king of bronze drum". In addition to all these, bronze drums continue to be collected and used among the people. ~

Ethnic groups in southern China appreciate these gong-like drums for their sound and their reputed ability to expel bad spirits. During important ceremonies have often been used as bowls for offerings and other religious practices. Every village considers its drums as their treasure. Therere are a number of myths about these bronze drums. The long poem sung by some peoples of Yunnan—"The Kings of the Bronze Drum"—describes a community that arrives from distant lands and through their long history have been protected by the bronze drums and alleviated their sufferings in hard times by providing a channel of communication to seek the help of the gods.

Bronze drum are believed to have been developed from bronze kettles. Hollow and bottomless, they look like round stumps, with flat surfaces and curled middle parts. Bronze drums are forged from copper and bronze and differ in size and weight. The largest one exceeds one meter in diameter while the smallest is only over 10 centimeters across. The heaviest weighs over a hundred kilograms while lightest weighs about a dozen kilograms. ~

Most bronze drum tops are engraved with lines simulating the sun, smoke plumes, clouds, combs and flags. Some of them images of frogs, tortoises, cattle and horses forged on their sides. The bodies of bronze drums are also decorated with many lines, drum ears and other adornments. According to their shapes, line decorations and forging craftsmanship, bronze drums can be classified into eight kinds: 1) Wanjiaba type, 2 Shizhaishan type, 3) Lengshuichong type, 4) Zunyi type, 5) Majiang type, 6) Beiliu type, 7) Lingshan type and 8) Ximeng type. Among them, Beiliu, Lingshan and Lengshuichong bronze drums, display the highest levels of skill and achievement of craftsmanship, smelting and foundry. ~

Bronze drums are the artistic treasure and are also considered as vehicles of magical power. The use and function of the drums can be diverse. In ancient times, they were mainly used for religious rites and many were hidden in caves or buried underground and were not allowed to be banged casually. Later they gradually became symbols of power of the rulers: used to gather people for a meetings or even to encourage the soldiers on the battlefield. It was thought that rulers could keep their power as long as the bronze drums were in their possession. Without them, the rulers would no longer hold power. In addition, these drums were also regarded as property that could distinguish the rich from the poor and humble. It was not until the Ming and Qing dynasties that the bronze drums began to be used as instruments. ~

Black Teeth and Dental Ablation Among Tribal People in South China and Southeast Asia

North Vietnamese girl with black teeth

Roger Blench wrote: Early texts describe the minorities of South China, and modern ethnography records distinctive practices such as dental mutilation and teeth-blackening. Some of these, at least can be confirmed in the archaeological record. Common synchronic material culture, such as idiosyncratic musical instruments, may also be used as additional evidence. [Source: Roger Blench, “The Prehistory of the Daic (TaiKadai)speaking peoples and the Hypothesis of an Austronesian Connection” presented at the 12th EURASEAA meeting Leiden, 1-5th September, 2008]

“Dental ablation or evulsion is the deliberate taking out of teeth, most notably the front incisors, but often others as well. It can be detected in the archaeological record as well as in ethnographic accounts, but has tended to disappear in recent times, like many types of permanent body mutilation. Its pattern in the Southeast Asian region is quite striking. It is not in use generally in island Southeast Asia (though see Van Rippen 1918) but is common on Taiwan (and incidentally associated with the millet harvest in some groups). A Tsou woman on Taiwan with dental ablation was photographed by Segawa in the 1930s (Yuasa 2000: 61). Yuasa (2000: 39) also reproduces a series of photographs of Tsou men, showing both ablation and teeth blackening.

“Ablation is recorded ethnographically and archaeologically in South China (and some sites in North China). Zhu Feisu (1984) reports ablation from pre-Qin sites in Guangdong. Chinese records also mention dental ablation and teeth colouring (Mote 1964). Ethnographically, a number of Daic peoples of South China still practise ablation. Photo 4 shows a Tai woman with her two bottom front teeth removed. Ethnographically, a number of Daic peoples of South China still practise ablation. Photo 4 shows a Tai woman with her two bottom front teeth removed. Tapp & Cohn (2003) have republished an eighteenth century album of ‘Savage Southern Tribes’ showing pre-marital dental ablation among the Gelao [Qiao] a Daic group (Photo 5).

“The distribution of dental ablation on the mainland in archaeological sites is also quite indicative. There is no record of its occurring in Daic-speaking peoples in Thailand today. The most comprehensive review of Southeast Asian dental ablation is Tayles (1996) who describes its occurrence at Khok Phanom Di. Sangvichien et al. (1969) report ablation from Ban Kao. Nelsen et al. (2001) argue for its presence at Noen U-Loke in NE Thailand (ca 200 B.C. to ca 500 AD). However, it is extremely common in dental material from Northern and central Thailand from about 3500 BP onwards1. Oxenham (2006) reports possible cases of ablation from the Da But period sites in Northern Vietnam. Photo 6 shows two skulls excavated in South China which also clearly illustrate dental ablation. The patterning shows that this cannot possibly be accidental tooth loss.

Teeth-blackening is distinct from betel-chewing and uses plant derived dyes to colour the teeth. It is reported among the various minorities on Taiwan, including the Tsou (see above). Chen (1968:256) says ‘Tooth-blacking was also common among the Paiwan and Ami’. Tooth blackening is also common among various Yunnan minorities and is referred to in the Chinese historical sources cited above. The usual plant used for this purpose, both in Taiwan and Yunnan is the fevervine, Paederia scandens (Photo 7) (see also Yuasa 2000: 61). However, teeth-blackening is also common among the Vietnamese (an Austroasiatic-speaking people). Here is Frank (1926:168); ‘about marriage time, which in Annam is early in life, every Annamese, of either sex, is expected to have his teeth lacquered black by a process said to be very painful….and to the Annamese a person is handsome only if his teeth were jet-black. ‘Any dog can have white teeth’ say the Annamese, looking disparagingly at Europeans.’”

Han and T. Nakahashi wrote: “In China, as far as it is known at present, ritual tooth ablation first appeared among the people of the Shandong-North Jiangsu region, at least 6500 years ago, and then became very popular amongst the people of the Dawenkou culture of coastal China. China is represented by the bilateral ablation of the upper lateral incisors (2I2 type), and with the exception of a small group, showed no remarkable temporal change after its inception. [Source: Han and T. Nakahashi study, “A comparative study of ritual tooth ablation in ancient China and Japan”]

Tattooing and Body Alterations Among Tribal People in South China and Southeast Asia

Tattooing is common among many of the hill tribes. Some old men are covered in religious and mystical symbols and designs. Lawa men have tattoos of tigers and apes etched between their waist and knees as protection from evil spirits and wild animals. Marco Polo described tattooing among a tribe in Yunnan thought to be the Dai. Women in the Khmer-Loeu tribe stretch their ear lobs with bundles of sticks and wear plugs like tribes in Africa and the Amazon

Dulong facial tattoos

Roger Blench wrote:“Yue was a general name for a complex of loosely related ethnic groups which inhabited broad areas of southern China, often referred to as Bai yue (Hundred Yue). According to Records of The Late Han Dynasty – a History of the Southern Aborigines, ‘The two prefectures, Zhuya and Dan’er were on the island, about one thousand li east to, 500 li (~ 250 km) from south to north. The headman of the aborigines living there thought it was noble to make their ears long, so the people there all bored holes in their earlobes, and pulled them down close to their shoulders…. and called it Dan’er.’ Sima Qian (1993) in the section, Record of the Southwest and Southern Barbarians, part of Records of the Grand Historian in his states that the ancestors of the Dai in Yunnan were the Dian Yue . Fan Chuo (1961) in A Survey of the Aborigines (Tang Dynasty) refers to them as ‘Black Teeth’ and as ‘Face-Tattooed’. [Source: Roger Blench, “The Prehistory of the Daic (TaiKadai)speaking peoples and the Hypothesis of an Austronesian Connection” presented at the 12th EURASEAA meeting Leiden, 1-5th September, 2008]

The Tianbao shilu (Veritable Record of the Celestial Treasure Reign period) says that ‘the Jiu mountains in Rinan county are a connected range of an unknown number of li. A Luo (lit. naked) man lives there. He is a descendant of the Bo people. He has tattooed his chest with a design of flowers. There is something like purple-coloured powder that he has painted below his eyes. He has removed his front two teeth, and he thinks of it all as beautiful decoration.’

“Tattooing on the face was common with most Taiwanese groups. Under the Japanese occupation there was a violent and ultra-cruel campaign to eliminate it, hence it is hardly seen today. The Atayal had tattooing equipment. Tattooing is noted as a feature of the Yue in early Chinese descriptions and is still practised among groups such as the Gelao and Dulong today. Photo 2 shows typical face tattooing among the Trung [=Dulong], a Sino-Tibetan group in Yunnan. Tattooing is widespread but patchy in the region especially in the Austronesian world. For example, it is not typical of the Northern Philippines, but occurs in Borneo and Polynesia (Hambly 1925; Gilbert 2001). It does occur in Japan and Siberia, but in China proper it is never on the face and has a strong association with criminality (Ceresa 1996; Chen Yuanming 1999); hence its salience for Chinese historians of the ‘Southern Barbarians’. [Source: Roger Blench, “The Prehistory of the Daic (TaiKadai)speaking peoples and the Hypothesis of an Austronesian Connection” presented at the 12th EURASEAA meeting Leiden, 1-5th September, 2008]

See Dai Tattoos and Black Teeth Under DAI MINORITY CULTURE: CLOTHES, ART AND DANCE factsanddetails.com and DERUNG (DULONG, DRUNG) RELIGION, CUSTOMS AND TATTOOS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: CNTO, Johomaps, Nolls China website Autef.com, Columbia University, San Francisco Museum, Travel Pod.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2022