MIAO CULTURE AND ART

The Miao have a highly diversified culture developed from a common root. They are fond of singing and dancing, and have a highly-developed folk literature. Morma Diamond wrote: The Miao are well known for the complexity, sophistication, and variety of their weaving, embroidery, and brocade and batik work, though little of it is commodified. Their elaborate silver jewelry is also famous. Generally the Miao do not have graphic arts. [Source: Norma Diamond, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

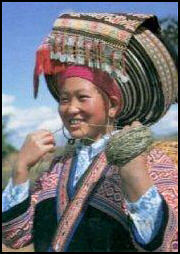

The Miaos create a variety of colorful arts and crafts, including cross-stitch work, embroidery, weaving, batik, and paper-cuts. Their batik technique dates back 1,000 years. A pattern is first drawn on white cloth with a knife dipped in hot wax. Then the cloth is boiled in dye. The wax melts to leave a white pattern on a blue background. In recent years, improved technology has made it possible to print more colorful designs, and many Miao handicrafts are now exported. Miao clothing incorporates hundreds of styles in varying arrays of color. Headdress is common, often using flowers to accent vibrant patterns.

Embroidery, wax printing, brocade, and paper-cutting are four famous crafts of the Miao. The Li, Miao and Yao peoples produced many kinds of textiles such as Bolup cloth, Mao (hawksbill) cloth, Zhu cloth (light blue or white cotton cloth), Yaoban cloth (blue batik with white speckles), ramie cloth and kapok cloth. Wax printing is a unique technique developed by some Chinese ethnic groups for printing and dying hand-made cloth. The blue and white pattens reveal natural cracks made when wax cools.

The most sacred and revered form is Miao art is the pa ndau ("flower quilt"), a stitched story cloth that measure around 8-by-10 feet and depicts myths and histories. After the Miao written language was lost, the Miao say, pa ndau were critical in transferring knowledge from one generation to the next. The Miao deliberately do no make art with supernatural being to differentiate themselves from the Han Chinese. The geometric patterns found on pa ndau are also placed on their shirts, dresses, and burial shrouds using indigo batik and applique. The Miao and Dong people are well-known for using ox-horns in their carvings.

See Separate Articles: MIAO MINORITY: HISTORY, GROUPS, RELIGION factsanddetails.com; MIAO IN GUIZHOU IN THE 1900s factsanddetails.com; GUIZHOU IN THE 1900s: BANDITS AND ROUGH TRAVEL factsanddetails.com MIAO MINORITY: SOCIETY, LIFE, MARRIAGE AND FARMING factsanddetails.com ; MIAO AND DONG AREAS OF GUIZHOU PROVINCE factsanddetails.com GUIZHOU PROVINCE, THE GUIYANG AREA AND THE ETHNIC GROUPS THAT LIVE THERE factsanddetails.com ; HMONG MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION AND GROUPS factsanddetails.com; HMONG LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE, FARMING factsanddetails.com; HMONG IN AMERICA factsanddetails.com; HMONG, THE VIETNAM WAR, LAOS AND THAILAND factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Hmong/Miao in Asia” by Nicholas Tapp, Jean Michaud, et al. Amazon.com; “Butterfly Mother: Miao (Hmong) Creation Epics from Guizhou” by Mark Bender Amazon.com; “The Art of Ethnography: A Chinese "Miao Album"” by David Deal, Laura Hostetler, et al. Amazon.com ; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Traditional Furniture, Vol. 2: Ethnical Minorities” by Fuchang Zhang Amazon.com; Textiles, Clothes, Jewelry: “Miao's Attires” by Wan Zhixian, Yan Da, et al. Amazon.com; “Ethnic Miao Silver” by Yu Weiren and Wan Zhixian Amazon.com; “Every Thread a Story & The Secret Language of Miao Embroidery” by Karen Elting Brock, Wang Jun, et al. Amazon.com; “Miao Textiles from China” by Gina Corrigan Amazon.com; “The Roots of Asian Weaving: The He Haiyan collection of textiles and looms from Southwest China” by Eric Boudot and Chris Buckley Amazon.com; "Drawing Flowers": Miao Batik Textiles From Zai Yong” by Monique Wollan Amazon.com; “Writing with Thread Traditional Textiles of Southwest Chinese Minorities” by University of Hawaii Art Gallery Amazon.com “Embroidered Identities: Ornately Decorated Textiles and Accessories of Chinese Ethnic Minorities” by Mei-yin Lee, Florian Knothe Amazon.com; “Guizhou Batik” by Wan Zhixian and Ma Zhenggrong Amazon.com; “The Art of Silver Jewellery: From the Minorities of China, The Golden Triangle, Mongolia and Tibet” by René Van Der Star Amazon.com

Miao Literature and Folklore

The Miao have no written records, but they have a rich oral literature of myths, history and folk tales and many legends in verse, which they learn to repeat and sing. Some Miao recorded their lives and stories on stitched story cloths. The Black Miao treasure poetical legends about creation and a great flood. These are composed in lines of five syllables, in stanzas of unequal length, one interrogative and one responsive. They are sung or recited by two persons or two groups at feasts and festivals, often by a group of young men and young women.

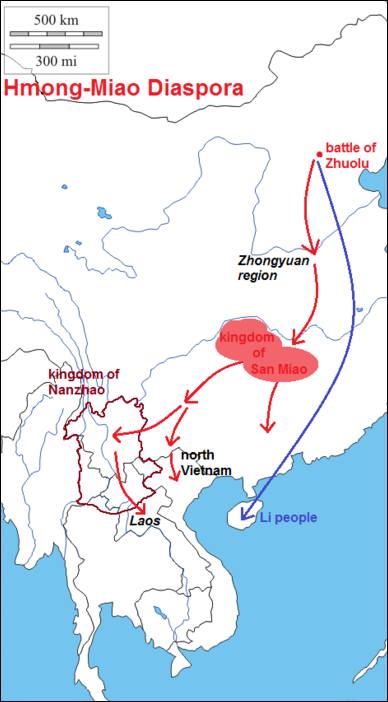

C. Le Blanc wrote: Miao myths describe the creation of the world, the birth of the Miao people, and their battles and migrations. A typical Miao creation myth is the ancient "Maple Song": White Maple was an immortal tree that gave birth to Butterfly Mama. She married a water bubble and then laid twelve eggs. The treetop changed into a big bird that hatched the eggs over a period of twelve years. When the eggs hatched, they gave birth to a thunder god, a dragon, a buffalo, a tiger, an elephant, a snake, a centipede, a boy called Jiangyang, and his sister. So Butterfly Mama was the mother of God, animals, and human beings. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Samuel R. Clarke wrote in “Among the Tribes of South-west China” in 1911: “The Miao have plenty of legends handed down from earlier times. Who composed these legends no one knows: they are taught by the older people to the girls and boys. Many of them are in verse, five syllables to a line, the stanzas being of unequal length, one stanza interrogative and one responsive. These are sung or recited at their festivals by two persons or two groups, generally one group of young men and one group of young women, one group interrogating and the other responding. Among these legends, which I have written down from the dictation of my Heh Miao teacher, is a story of j the Creation and a story of the Flood. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

Not only do the Miao sing and recite the old legends in verse, handed down from very early times, but they are also, or at least some of them are, great story-tellers. Some of these stories I took down from the dictation of my Miao teacher. They are not like Chinese stories, which are moral or immoral — mostly moral. Miao stories are not moral, but if we should say they were immoral, it might suggest a wrong opinion of them. We might, I think, call them unmoral, for they do not teach or illustrate the beauty of filial piety, loyalty, truthfulness, or any other moral excellence. In their stories one or more persons are clumsily crafty, and other persons are preternaturally simple. It is the crafty or lying people who always come off best, to the confusion of all honest and simple folk. That sort of thing amuses them immensely. Some of their stories profess to explain in an amusing, if not satisfactory, way how certain things happen to be as they are” such as “why they have no written characters, and why the sun rises when the cock crows.

In one well-known Miao story, men and monkeys used to live in harmony, but man was jealous that the monkey's fields produced more rice than his so he tricked the monkey into exchanging fields with him. Even then man wasn't satisfied. When the monkey — hungry because his fields were so unproductive — asked man what he should do, man told the monkey to kill his children, which would leave him with more food. The monkey took the advise and murdered all of his children. That night man sneaked into the monkey's house and gathered up the bodies. The next day the monkey found the man eating something and asked him what its was. "Only bird's intestines," the man replied. Not long afterwards the monkey realized the truth, and in a rage decided to live in the forest. Now he only comes in out of the forest to steal man's crops because man had deceived him and stolen the souls of his children.

Miao Creation Myths

According to one Miao creation myth, many, many years ago men lived underground with the animals and the world was nothing but black rock. One day a man and his wife followed a monkey and a dog through a series of long tunnels that lead to the surface of the earth. Upon seeing the nothingness that covered their planet the man and women returned to their subterranean world to collect some seeds and worms which they brought back to the surface. From the seeds sprouted plants, which in turn multiplied bringing life to the earth.

The legend of the creation by the Black Miao goes:

“Who made heaven and earth?

Who made insects?

Who made men?

Made male and made female?

I who speak don't know.

Heavenly King made heaven and earth,

Ziene made insects,

Ziene made men and demons,

Made male and made female.

[Source: E. T. C. Werner, Myths and Legends of China (London: George G. Harrap and Company, 1922), pp. 406-408]

“How is it you don't know?

How made heaven and earth?

How made insects?

How made men and demons?

Made male and made female?

I who speak don't know.

Heavenly King was intelligent,

Spat a lot of spittle into his hand,

Clapped his hands with a noise,

Produced heaven and earth,

Tall grass made insects,

Stories made men and demons,

Made men and demons,

Made male and made female.

How is it you don't know?

Made heaven in what way?

Made earth in what way?

Thus by rote I sing,

But don't understand.

The poem then goes on to relate how heaven and earth were kept apart after they were separated. They tried all sorts of wood and all sorts of metal, and at length decided to prop up heaven with pillars made of silver. But where were they to get fire to melt the silver? Fire had gone up to heaven: how were they to bring it down? Fire eventually came down from heaven in a stone, and with raw steel and tinder they extracted the fire from the stone. After heaven had been propped up with silver pillars, the sun and moon and milky-way were fixed in their places. The sun, however, went away and would not come back. Thereupon they sent various beasts and birds to call the sun to return, but they would not go: or if they went, the sun refused to come at their call. Finally, they sent the cock to call the sun to return, and when the cock crew the sun came back. The poem concludes that the proof of this is that when the cock crows the sun rises! [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

Miao Flood Myth

The Miao have many versions of a Noah-like flood story. The version told to H. J. Hewitt by the Hua Miao goes: Two brothers ploughed a field one day, and next morning found the soil all replaced and smoothed over as if it had never been disturbed. This happened four times, and being greatly perplexed they decided to plough the field over once more and observe what happened. In the middle of the night while the brothers were watching, one on one side of the field and the other on the other side, they saw an old woman descend from heaven with a board in her hand, who, after replacing the clods of earth, smoothed them with the board. The elder brother at once shouted to the younger one to come and help him to kill the old woman who had undone all their work. But the younger brother suggested that they should first ask her why she did this and put them to so much trouble. So they asked the old woman why she had acted so, and made them labour in vain. She then told them it was useless for them to waste time in ploughing land as a great flood was coming to drown the world. She then advised the younger brother, because he had been kind to her and prevented the elder brother killing her, to save himself in a huge wooden drum. He was to cut down a tree, hollow it out from the bottom upwards, and nail a piece of skin over the opening. She told the elder brother, because he had wished to kill her, to make for himself an iron drum. They were each to retire into their respective drums when the flood came. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

When the flood came and the waters rose, the younger brother invited his sister to take refuge in his drum, and she did so. The elder brother was drowned in his iron drum, but the younger brother and his sister were safely preserved in the wooden one. The waters rose half-way up to heaven, and so high were the brother and sister carried in the hollow tree. With the rush of water they were carried hither and thither, and the tree at length was seen by one of the Genii of heaven, who thought it was some huge creature with as many horns as the tree had branches. He was very much alarmed, and said: “I have only twelve horns, but this thing has many more: whatever shall I do? “ Thereupon he cried out for the dragon, lizards, tadpoles, and eels to clear out the channels and make holes for the waters of the flood to recede, and thus deliver him from the monster with so many horns.

Through the efforts of the dragon and his crew, after twenty days the waters subsided, and the hollow tree stuck half-way down a steep and dangerous precipice. Then it came to pass that an eagle built its nest and hatched two young ones. This suggested a mode of deliverance from their difficult situation to the young man. He plucked some hair from his head, plaited a small cord, and with this tied the wings of the young eagles so that when they were fledged they were unable to fly.

The mother-bird was much perplexed when in due time her young ones could not fly, and went to consult a fairy about it. The fairy said, ''Go and ask the stem of the tree near to which your nest is built, and it will tell you what to do. In return for this you must take the tree and fly away with it down to the ground.'' So the bird flew back to its nest, and addressing the tree, said: “Let my young ones fly, I pray thee.'' The man in the tree rephed, “If I let them fly will you carry me down to the ground in safety?” The eagle promised to do so, and the young man at once unfastened the cords he had tied round the wings of the young eagles, and they were immediately able to fly. Then the eagle took the tree, with the brother and sister in it, and flew with it down to the ground. On coming out from their late abode, these two survivors found themselves in great straits. They had no companions, no fire, and no rice to eat. The brother seeing a red bird not far from him, picked up a piece of old iron and struck at it. The bird flew away, and the iron struck a rock which gave forth a spark. Thus they discovered the way to get fire, and having gathered some dry stalks, they made a fire at which they warmed themselves.

In most versions of the Miao flood story only two people were saved in a large bottle gourd used as a boat, and these were A-Zie and his sister. After the flood the brother wished his sister to become his wife, but she objected to this as not being proper. At length she proposed that one should take the upper and one the lower millstone, and going to opposite hills should set the stones rolling to the valley between. If these should be found in the valley properly adjusted on above the other, she would be his wife, but not if they came to rest apart. The young man, considering it unlikely that two stones thus rolled down from opposite hills would be found in the valley, one upon another, while pretending to accept the test suggested, secretly placed two other stones in the valley, one upon the other. The stones rolled from the hills were lost in the tall wild grass, and on descending into the valley, A-Zie called his sister to come and see the stones he had placed. She, however, was not satisfied, and suggested as another test that each should take a knife from a double sheath and, going again to the opposite hilltops, hurl them into the valley below. If both these knives were found in the sheath in the valley, she would marry him, but if the knives were found apart, they would live apart. Again the brother surreptitiously placed two knives in the sheath, and, the experiment ending as A-Zie wished, his sister became his wife. They had one child, a misshapen thing without arms or legs, which A-Zie in great anger killed and cut to pieces. He threw the pieces all over the hill, and next morning, on awakening, he found these pieces transformed into men and women. Thus the earth was re-peopled. [Source: E. T. C. Werner, Myths and Legends of China (London: George G. Harrap and Company, 1922), pp. 406-408]

Miao Stories

The story “The Dog, the Cat, the Rat, and the Sheep” goes: "Once upon a time the dog and the cat agreed to be cousins. The dog said, ‘We two have now agreed to be cousins, there must be no steaHng between us. The cat repHed, ‘We shall steal other people's things: we two are kinsfolk, how can we rob one another?’ Not long afterwards the dog took off his horns, and putting them on one side, stooped down to lick the inside of a stone mortar. In a little time he straightened himself, looked around, and not seeing his horns, said to the cat, ‘Have you seen my horns? ' The cat replied, ‘I have not seen them. I certainly do not look after your horns for you.' [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

''The dog searched everywhere, but could not find them, and meeting the rat, he asked if he had seen them. The rat answered, ‘I know where they are.' ' Well,' said the dog, ‘you tell me where they are.' The rat replied, ‘Your cousin the cat has stolen your horns and put them in a cupboard.' The dog went to the cupboard and found it was shut, so he said to the rat, ‘You et in and bring them out for me.' The rat inquired what reward he should get for doing this, and the dog replied, ‘When I eat anything, you shall eat with me.'

“So the rat gnawed a hole in the cupboard, and dragged out the horns with his teeth. As he was doing this the cat saw him, and snatched them away. The dog thereupon pursued the cat, and the cat made off to the top of a tree. The dog at the foot of the tree cried out, ‘Beat him 1 ' The cat at the top of the tree said, ‘Fm not afraid.' When it was dark the dog went home, and the cat, coming down from the tree, gave the horns to the sheep. And now the cat worries the rat, and the dog likes to chase the sheep and bite them. So instead of friendship there is enmity between them all, because of things that happened long ago."

The Miao story “The Swallow and the Toad” goes: “In old times the rice plant bore grain from the bottom to the top of the stalk. This just suited the swallow, but the toad did not like it. ' It would be well,' said he, ‘if instead of one harvest in the year there were three harvests per annum.' 'No,' said the swallow, 'it would be better if one harvest yielded enough for three years.' ' That,' objected the toad, ‘would be very bad.' ' How would it be very bad? ' asked the swallow. ' Because,' replied the toad, ‘the ground would be overgrown with weeds/ ' But/ urged the swallow, ‘the weeds would be very convenient, we could rest in the shade of them/ ' You only think of yourself,' said the toad. ' Well,' asked the swallow, 'how would it be bad for 3ou?' 'I prefer,' said the toad, 'that there should be three harvests every year; thus there would be no weeds, and the snakes would not be able to seize me.

''The swallow, however, would not agree to any such arrangement, and so they quarrelled. ' You go,' suggested the swallow to the toad, ‘and make an accusation against me.' ' Accuse you! ' cried the toad: ‘yes, I certainly shall go and accuse you.' The swallow thought the toad would be a long time on the road, so he said to the toad, ‘You go first. I'll come along at my leisure.' ' The toad, however, was clever. He took a piece of wood and threw it in the water, and getting upon the piece of wood he floated quickly down with the stream. In this way he was the first to arrive before the king.

“The king asked him what he came about, and the toad replied, ‘I have come to make an accusation.' ' Concerning what matter,' inquired the king, ‘do you wish to make an accusation?' ‘I desire,' said the toad, 'that there should be three crops every year to supply the year's need. The swallow will not agree to this, and says he prefers that one year's crop should suffice for three years. I say that thus the ground would be overgrown with weeds, and the snake would come and eat me. So we quarrelled over it, and the swallow beat me.' Thereupon the king allowed the claim of the toad that every year there should be three crops, and the toad returned to his home.

“Later on the swallow, having delayed and amused himself on the way, arrived. The king asked him, ‘What have you come about? ' The swallow replied, ‘I have come to make an accusation.' ' Concerning what matter,' demanded the king, ‘do you wish to make an accusation? ' ‘I desire,' said the swallow, ‘that one harvest should suffice for three years. The toad will not consent to this, and he beat me, so I have come to accuse him.' ' But,' said the king, ‘the matter is already decided. You will find it recorded here. You can read it.' The swallow, seeing the toad's claim was allowed, kept on protesting, whereupon the king with his hand hit the swallow on the top of the head, and ever since the top of the swallow's head has been flat."

Miao Music and Dance

The Miao also enjoy music. Antiphonal (alternate singing by two singers or groups) songs are sung by courting couples. The playing of lusheng, a reed pipe, is said to be an expression of Miao history and customs. The lusheng is played at festivals and major celebrations. The ability to improvise, especially when singing, is highly valued.

Miao songs do not rhyme and vary greatly in length from a few lines to more than 15,000. The Miao are generally adept singers and dancers and specialize in love songs and songs for toasting. The Lusheng is the most commonly used musical instrument during musical serenades or feasts . In addition, flutes, copper drum, mouth organs, the xiao (a vertical bamboo flute) and the suona horn are also very popular. [Source: China.org |]

Popular dances include the lusheng dance, drum dance and bench dance. Hunan province the Miao do a drum dance. The Banjiawu dance of the Miao and pestle dance of the Gaoshans are depictions of farm labor.

“Song and dance are an important part of Miao life. There are many special songs, including love songs, funeral songs, and wedding songs. The Miao also sing as part of the group dating custom. Miao songs are often poems that the singer makes up as the song is sung using rhyme and clever wordplay. Older songs may be memorized, but the singer adds his own lines to them. Miao dances express both sadness and joy. Sometimes the dancer play the lusheng as they dance.

Miao Reed Pipes

Miao musical instruments consist mainly of pipe instruments—such as reed pipe, vast bobbin, night vertical bamboo, sisters' vertical bamboo and bamboo flutes—and percussion instruments—such as bronze drum, wood drum and bronze gong. Among them, the reed pipe is the most popular and characteristic instrument. During festivals, auspicious days, weddings, building new houses, and welcoming honorable guests, people play reed pipes while singing and dancing. It is said the saying "reed-pipes are indispensable to the Miaos" has existed since the ancient times. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

The reed pipe is usually composed of three parts: the pipe, the cup-shaped body and the reed. Commonly used ones are installed with six pipes. On the surface of the pipes are holes which can be for pressed to make different notes. The lower part is installed with bronze reeds. The pipes are inserted into a rectangle cup-shaped wood or gourd, with one sound coming from each pipe. One bamboo pipe is put in two or three pipes that serve as a resonant pipe. ~

Reed pipes come in different types according to the length of the pipes. Small ones are only ten centimeters long, and big ones can be three to four meters long. Modern versions of the instrument can have over ten to twenty pieces, and produce a wide range of sound. In some place not only is Miao music played with the reed pipes, popular Chinese songs can be played as well. The timbre of reed pipes is very bright, simple and vigorous. The pipes can be used as a solo instrument or played in an ensemble of two or more instruments. They have been used to accompany the reed-pipe dance among the Miao people since ancient times. ~

Miao Reed Pipe Dances

The reed-pipe dance has a long history and is the most representative dance of the Miaos. "The Song History" records that "one person played the gourd reed-pipe— several generations danced together mildly, and stepped on the ground to the rhythm." Today the dance is most popular in certain places. The Reed-pipe dance in southeastern Guizhou is divided into line dances and step dances. In the line dance, dancers hold reed pipes, stand in line and dance while turning around with the main pipe player as the axis. While dancing, they always keep the line straight. Girls are arranged around the reed-pipe team and dance slightly to the rhythm of the reed pipes. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

In the stepping dance two persons play a pair of pipes of the same size together and lead the dance. Dancers circle around and follow the leaders. The stepping hall dance of the Miao in Rongshui, Guangxi Province is famous for its mass participation. On wide stepping ground, dozens of reed pipes are played together, and hundreds, even thousands of people dance around them.

The reed-pipe dance in Western Guizhou, Yunnan and Sichuan is interesting. In addition to the collective dance that everyone knows, there is performance dance that includes some acrobatic movements. This dance can be done by one, two four or eight persons. In Yuanyang, Yunnan Province, a performer climbs up a flowery pole of several meters high while playing reed-pipe, pick up an object and comes down. When about one or two meters before reaching the bottom he turns a somersault while playing the reed pipe, drawing a big applause. Among the other moves are: " standing upside down", "earthworm rolls on sand", " holding persons on shoulders", " getting over wooden bench", "turning a square table round", " walking on bamboo stick", " stepping on eggs", and " rolling a bowl with water in it".

Describing Miao Festival Music in the 1900s, Samuel R. Clarke wrote in “Among the Tribes of South-west China”: “The musical instrument they play, at these festivals they call Ki, and the Chinese call it Lu sen or “six tones." They are made of bamboo pipes, sometimes six being let into a piece of wood like a hollow club, the handle of which is the mouth-piece. The noise — perhaps we ought to say sound — is produced by a brass tongue attached to a small metal frame (such as are used in concertinas and harmoniums) let into the bamboo tube, one in each of them. The sound is something like the sound of the bagpipes. They are made in sets of different sizes, the smallest having pipes about three feet long, and the largest with pipes twelve or fourteen feet long. The lower end of the large pipes is put into a drum or cylinder three or four feet long, hollowed out of the trunk of a tree. These large reeds give forth a very creepy sound, the lowest note, we believe, to which mortal ears are sensible. The tunes they play are very monotonous. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

At the Heh Miao festivals, five players in a row, with instruments of different sizes, wheel round and round the man who plays the large pipes with the drum. A row of five young women go round with them, sometimes facing them and moving backwards, sometimes behind and following. To alter their position the young women wheel outside of the circle, let the pipers go round, and then wheel in again. This they call dancing, but there is no real dancing about it: it is merely pacing, yet it seems to interest them, and they do it very seriously. We think it must be reckoned bad form for them to laugh or smile while thus engaged, for we have seen the girls severely exerting themselves to keep their faces straight, when they evidently wanted at least to smile. As for the pipers, it is no laughing or smiling matter for them. They exert themselves so much that their cheeks are swollen, their eyes seem to stand out of their heads, and the perspiration streams down their red faces. We have seen thirty or forty of these groups of ten, circling round on one plot of ground, hemmed in by hundreds of spectators. The sound of so many pipes all playing independently at the same time and place is certainly not music, and soon becomes positively exasperating to some ears. On the edge of the crowd are sweetstuff and cake sellers, and other hawkers moving about.

Miao Horse Fighting

The Miao like horse races, which are often held on holidays. In some places horse fighting is popular. Rongshui in Guangxi province is a famous Miao area famous for retaining many special cultural customs, such as horse fighting and "pulling drum". Horse fighting is a traditional entertaining activity of the Miao in Rongshui, and it is often held in different festivals, with the horse fight festival from the 26th to the 28th in December, the grandest. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

On the first day of the festival, every family butchers chickens and ducks, steams polished glutinous rice and makes sweet wine. They also go to their fields to catch fish by drawing off water, and cooking fresh fish gruel to entertain relatives and friends from far away. Horse fight and horse race are held on the second and third days of the festival. Horse fights are very thrilling, exciting and fascinating match. At about 10 in the morning, the surrounding space of the fight site is crowded with many people. After some indigenous "Guoshanchong" guns are fired, two groups of powerful horses enters the fight accompanied by a reed pipe team and lion dance team. ~

When a match begins, a judge announces the list of horses joining the fight, one horse from each of the two teams is brought to the fighting site . After the halter is released, the two horses rush toward each other at once. They bite each other, turn their hoofs and kick, and raise their front hoofs in the air and confront each other. Smoke and dust fill the air; spectators hold their breath, cheer and jump for joy and applaud loudly. After a certain number of rounds, if one horse falls down or runs away, the other wins, and another two horses get into the site to begin a new fight. The Single elimination system is used, with winning horses moving on to the next round. Half the horses are eliminated in each round, until the last two horses fight it out for the championship. After the championship match finishes, people drape a red cloth over the winner's back. The owner of the horse is not only awarded, but also feels very proud of having such a brave and strong steed. ~

Miao Embroidery

Embroidery refers to the traditional handicraft of weave figures on fabric with a needle and colorful threads. Embroidery skills are highly valued by the Miao. Almost every Miao woman is good at embroidering, often using the art form to decorate her clothes and the clothes of her family. Trousers, skirts, shoes, hats, socks, scarves, handkerchiefs and belts—fancy clothes worn to festivals and common dress and articles for daily use— are all embroidered with elegant figures and designs. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

Miao embroidery has a very long history. Historical records after the Tang Dynasty have many descriptions about it. Miao women passed on their skills from generation to generation and has traditionally been an important component of not only Miao culture, but Chinese national culture. The Miao embroidery has both a strong national style and local character. In additional to embroidery, the wax printing of the Miao is also very famous. ~

One of the characters of Miao embroidery is that its colors are rich, bright, clear and passionate. Red and green are main colors, and they are supplemented by other colors. The designs are dense which makes the colors more gorgeous, rich and splendid. Another character is that the shapes and lines are exaggerated and vivid. Figures of the Miao embroidery come from daily life, but they don't simply reflect life: careful observation and experience has taught Miao women how to emphasize outstanding features of the flowers, birds, worms, and fish they make, plus express their own feelings and Miao symbolism. ~

The Miao embroidery usually uses paper-cut to create the base shapes. Some women embroider spontaneously. The shapes, colors and structures are elaborately designed beforehand. Common figures include unicorns, dragons, phoenixes, fish, frogs, birds, butterflies, geometric figures and plant figures,. Through artistic abstraction, Miao women exaggerate and deform images to express aesthetic ideals and Miao interpretations of common symbols. For example, the fish with a round head, fat body, small mouth and big eyes is regarded as vivid and lovely. Designs, patterns and shapes should be symmetrical, natural and harmonious. Dragons, phoenixes, flowers, grass, worms and fish, should all be symmetrically arranged, especially in stitching embroidery. On top of this the different patterns of images are put together freely in an interesting way. ~

Different Styles of Miao Embroidery

There are different ways of embroidering: flat embroidery, plaited embroidery, knit embroidery, wound embroidery, crape embroidery, stitching embroidery, stretching embroidery, rolling embroidery, embroidery with split thread and sticking embroidery. 1) Flat embroidery is the most commonly used method. Employing two needles used together, it is simple, ingenious and flat, which is suitable for embroidering small figures. 2) Plaited embroidery means to plait 8-12 colorful silk threads into a "braid" and sew it into a cloth. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

3) Knit embroidery refers to inserting a needle in the cloth with a round thread on the needle and taking out the needle. 4) Stitching embroidery is used stitch regular geometric figures and deformed flowers, birds, butterflies. The structure should be balanced and symmetrical according to the latitude and longitude lines of the cloth. 5) Sticking embroidery is used to create cloth mosaics from little pieces of stitched silk and satins, joined together into designs and figures on cloth, and lock-stitch the border. This kind of embroidery is rough and tasteful, and is often used on big designs and figures. ~

6) Crape embroidery is complicated. The first step is to plait colorful silk threads into braid like plaited embroidery. The braids are stitched into different figures in different ways according to the structure. 7) Embroidery with split thread is very difficult and creates very subtle designs. It means to divide a thread into several plies, and thread a needle with each embroider all kinds of designs with the individual plies. This style of embroidery makes the most delicate, fine and smooth designs. ~

Miao Beauty and Hairstyles

Miao often wear complex necklaces, bracelets, earnings and headdresses Women wear their hair in topnot surrounded by a towel. In the old days both men and women had gapping holes in their ear lobes. Men used to put ivory stoppers in their holes and women put in wooden disks in theirs. The Miao don’t have a lot of body hair. Miao children are amazed by the hair growing on white people's arms. Sometimes they'll try to yank some off as a souvenir.

The Miao used to consider a full set of teeth to be ugly. In the old days each village had a "dentist" who charged one chicken for every four teeth he treated. During the treatment the teeth were chipped and filled into sharp points and then covered with shiny black lacquer made from tree sap.

Umbrellas were once considered prized possessions among Miao women, who used them primarily for protection from the sun. The Miao equate fair skin with status. The dark-skinned Lao Theung sub-tribe are looked down upon by other Miao.

Some Miao, have really long hair. According to the Guinness Book of Record, Hu Sengla, a Miao man who lived in northern Thailand, had the world’s longest hair. It reached a length of 5.79 meters. He washed his hair only once a year, mainly to earn money from tourists. His brother, Yi Sengla, had the world’s second longest hair. His was 5 meters long. A younger brother cuts his hair.

Miao Clothes

Miao are famous for their traditional costumes and wonderful embroidery. Women wear black tunics and pleated skirts, or calf-length black trousers with a short black skirts, or maroon or colored jacket or shirt with a colorful vest along with silver ornaments, and a turban-like headdresses strung with dangling coins. They sometimes sport silver rings around their necks. They also wear distinctive colorfully-embroidered aprons which Miao women believe can be dipped in water and used as a wash cloth to cure their husbands of any illness. Many wear gaiter that reach from the knees to the ankles.

Miao men have traditionally worn black short-sleeve tunics, with beautiful embroidered panels on the chest, and black baggy trousers with a crotch so deep it almost touches the ground. Draped around their shoulders and waist are sashes and bandolier-like belt hung with silver coins. On their head they wear turbans, satin skullcaps with pink pompons, or caps that look like crosses between a fez and a yamuka. "Black" Miao men wear dark skull caps, indigo homespun tunics, with embroidered colors, over long shirts and wide pants, held together by a wide, embroidered belts. Sometimes they have silver loops around their neck, bronze bracelets and a dagger in their belt.[Source: Spencer Sherman, National Geographic, October 1988]

The Miao wear all kinds of clothes and adornments, whose materials, colors and styles are often attractive bright and colorful. In China, the Miao are known for wearing the most elaborate and largest variety of costume of all of China’s ethnic groups. Men and women generally wear a short sarong. Many Miao women wear pleated sarongs. The ones worn in southeastern Guizhou are only 30 centimeters long.

Clothing styles can vary quite a bit from area to area as the Miao have a large population and scattered over a large area. In China alone, clothes styles are divided into five big types, with 480 sub-types and kinds. The five types are: 1) Southeastern Guizhou style, 2) Mid-southern Guizhou style, 3) Sichuan-Guizhou style, 4) Western Hunan style and 5) Hainan style. The Miao clothes and adornments are famous worldwide, and often feature delicate embroidery and splendid silver decoration. Although sewing methods the the skill and artistry are of a high level. The silver adornments in the southeastern Guizhou are especially varied, elaborate and characteristic. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

In northwest Guizhou and northeast Yunnan, Miao men usually wear linen jackets with colorful designs, and drape woolen blankets with geometric patterns over their shoulders. In other areas, men wear short jackets buttoned down the front or to the left, long trousers with wide belts and long black scarves. In winter, men usually wear extra cloth leggings known as puttees. Women's clothing varies even from village to village. In west Hunan and northeast Guizhou, women wear jackets buttoned on the right and trousers, with decorations embroidered on collars, sleeves and trouser legs. In other areas, women wear high-collared short jackets and full- or half-length pleated skirts. They also wear various kinds of silver jewelry on festive occasions. [Source: China.org |]

Importance of Miao Clothes

The traditional dyed Miao blue dresses worn by older women are often plain compared to the ones younger women wear. According to the BBC: By the time they are seven years old, girls learn complex embroidery to create these sensational garments. Older women and men usually wear simple, heavy silver necklaces; the intricate jewellery is only for younger women. [Source: Runze Yu, BBC, October 13, 2017]

On Miao ritual attire they have on display, the Shanghai Museum says: The Miao people do not have a written language. Miao clothing is a kind of symbol, which records the history and culture of the Miao through ‘special languages’ like style and decoration, telling the difficult and tortuous survival story of the Miao people over thousands of years.

Guzang dress is the costume of the ‘Guzang host’ during the Miao traditional ancestor worship Festival – the Guzang Festival. The dress is entirely covered with various natural patterns, including the sun, the moon and stars, flowers, birds, grass and insects, as well as various patterns implying the ancestor worship of the Miao people.

Guzang dress is the costume of the ‘Guzang host’ during the Miao traditional ancestor worship Festival – the Guzang Festival. The dress is entirely covered with various natural patterns, including the sun, the moon and stars, flowers, birds, grass and insects, as well as various patterns implying the ancestor worship of the Miao people.

Guzang dress is unique in shape and structure: no seaming on either of the flanks with chicken feather ribbon decorated on the bottom edge, which might be related to the old tradition of wearing pull-over and feathered clothes. This dress is woven in a geometric pattern with a swastika character in between in antique and elegant color. The Guzang Festival was held every 13 years in the past and large numbers of cattle were killed for the ancestral sacrifice, causing a great waste of resources. People now can witness such symbolic festivals as tourist attractions.

The Miao produce wonderful embroidered cloth. A Japanese craftswoman. Mayuko Takano, told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “the items are produced with a delicate care that is seldom seen in Japan.” The Li, Miao and Yao peoples produce many kinds of textiles such as Bolup cloth, Mao (hawksbill) cloth, Zhu cloth (light blue or white cotton cloth), Yaoban cloth (blue batik with white speckles), ramie cloth and kapok cloth. Wax printing is a unique technique developed by some Chinese ethnic groups for printing and dying hand-made cloth. The blue and white pattens reveal natural cracks made when wax cools.

Long Journey to Miao Dying

Reporting from Mingyue in Sichuan Province, Jonah M. Kessel wrote in the New York Times’s Sinosphere: “I once saw a photo of a man with blue hands. They belonged to an artisan textile dyer, an ethnic Miao who goes by the name Han Shan, or Cold Mountain. Intrigued, I requested a meeting.“To put it simply, to us dyeing means life,” he said in the courtyard of the monastery, as we sipped tea under a full moon. I asked him to explain. Speaking in the third person, he told his story.He described a boy who grew up in a village in the mountains of Guizhou Province and the textile dyeing tradition of the Miao people. While other ethnic groups in southern China also use natural dyes, the Miao dye is known for its vibrant blue color, which comes from what Han Shan called the “blue herb,” or baphicacanthus cusia. [Source: Jonah M. Kessel, Sinosphere, New York Times, May 8, 2016]

“At 18, when it was time to further his education, Han Shan, like many young Chinese, moved to a big city, Chengdu, in Sichuan, with hopes of a better future. But after a year, he had become disillusioned with China’s urban dream. One day, he decided to walk away from the city. Literally. He set off on foot, with no specific destination, let alone purpose. It would become a journey of more than 2,000 miles and 15 years across Tibet, Xinjiang, Gansu, Ningxia and Yunnan. “I wanted to explore an unknown world,’’ he said. “To put it simply, I started walking because I was bored.”

“When asked how he spent his time over those 15 years, he decided it would be best to demonstrate. The next day, we set off through tea fields, bamboo forests and mountain paths. Along the way, he picked wildflowers, explaining their properties. “This flower can be used as a red dye,” he said, throwing one into a basket on his back. In Han Shan’s view, China’s modernization has come at a price: Society has lost its connection with nature. “We are developing so fast, we have forgotten where we came from,” he said. “Materialism is one of the core things that keep people away from nature.” For him, this carries dangers: “In Taoism we say: After the moon waxes, it wanes. Prosperity is the prelude to decline. Everything collapses when it reaches such extremes.”

“His answer to China’s materialistic society has been to retreat to this village, Mingyue, on the outskirts of Chengdu, where he cultivates a simple life. Ironically, perhaps, he survives by selling the clothing he dyes to the same people he considers too materialistic. The dyeing tradition was passed to him from his mother and to her, from many generations of Miao before. Now Han Shan has carried the tradition from Guizhou to Mingyue, where artists and free spirits like himself are creating a new space for themselves. Now, even some local villagers have taken up the dyeing trade.

Miao Silver Adornments

Miao women in Southeastern Guizhou Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture, home of one of the largest concentrations of Miao, generally like to wear silver adornments. The Miao here believe that the more silver adornments a woman wears, and heavier and more valuable they are, the more beautiful a woman looks. Some rich decorations are over 20-30 jins (10 to 15 kilograms) and make the whole body sparkle and shine with silvery light and sweat. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

On the silver neck rings worn by the Miao, Leonard Yiu, a collector of tribal costumes and jewelry, told the The Star (Malaysia): They would wear layer upon layer of them. Sometimes, there would be almost 25 kilograms of rings on their neck. “These items are all handmade and the workmanship is beautiful.” According to him, the neck rings and the designs also often denoted social status. For example, the dragon symbol was reserved for the blue-blooded and the toad symbolised fertility. [Source: Brigitte Rozario, The Star (Malaysia), September 17, 2006]

Miao are partial to silver adornments because they regard silver as a symbol of wealth. Silver adornments are beautiful, durable and easy to make. What's more, silver symbolizes light and health. It is believed that silver can drive out evil spirits, divert natural disasters and bring good fortune. Among the Miao’s silver adornments are: silver hats, silver horns, silver combs, “moon plates,” silver ear-rings, ear columns, ear pendants, neckbands, necklaces, bracelets and rings. Most of them have traditionally been made by hand by Miao silversmiths. Structural arrangements include symmetrical style, balanced style, connected style and radiation style. Among the skills and methods used to make silver adornments are casting, hammering, plaiting, cutting flowers and carving lines. Favorite animal and patterns like dragons, phoenixes, flowers and birds are often according to the personal requests of the owners. Treasured pieces have traditionally been handed down from mother to daughter or given as wedding presents. ~

Miao neckbands can be hollow or solid and are shaped like centipedes, columns, wound wire or twisted wire and boards. There are two kinds of necklaces: chain necklace and jingle bell necklaces. Chain necklace are comprised of dozens of round or elliptic solid rings. They are considered rough, thick, heavy and primitive. Jingle bell necklace are more delicately-made and elegant. The "moon plate" is a breast adornment worn by some women, so named because it is three-dimensional and empty like a half moon. Miaos' bracelets and rings come in a variety of shapes. There are whorl bracelets, worm bracelets, dragon head bracelets, bracelets shaped like the rolled leaves of the Juancaolan (a kind of plant). A Miao women dressed up for a festival or other event typically wears tree, fivem seven or eight bracelets on each wrist. ~

Miao Silver Hats

Silver hats worn by women are the main decorations of many Miao groups. Dazzling and extraordinarily splendid, these hats are generally composed of a “horse-tablet head” surrounded by silver slices, silver flowers, silver birds, and silver phoenixes. Images of a magpie stepping on aplum, a golden pheasant crying, a peacock spreading its tail, and male and female phoenixes perching together are lifelike, vivid and dramatic. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

The images vary from place to place. For example, the phoenix hat in the Huangping region in Guizhou Province is composed of hundreds of delicate flowers fixed on a half-hemisphere-shaped iron wire hoop to make a round hat that looks like the hats worn by imperial concubines in ancient times. At the middle of the top of the hat is a silver phoenix, flanked on each side by two birds with different shapes. At the front are three plates of different length hung side by side. Extending out the sides are silver horns or lings that situated under each plate and make a jingling sound when the wearer moves. There are three levels of girdle-shaped silver pieces at the back of the hat and they are like tail of the phoenix. There are eight pieces on the surface, twelve in the middle and five under them. The three levels are arranged according to their length. The surface level reaches neck, the middle level reaches shoulders and the lowest level reaches the waist—like the tail of phoenix. Each silver hat needs at least 3-4 jins (1½ to two kilograms) of pure silver. ~

Silver horns are one of the main features of head adornments for Miao women in Kaili, Leishan, Danzhai and Taijiang. They come in different thicknesses. Their shapes are like the horns of a big, strong bull. Some are decorated with a silver fan between the two horns. The silver horns are 50 to 70 centimeters long, and are carved or hammered into the patterns of two dragons grabbing jewels or phoenixes. Some are decorated with feathers or tassels. Their weight is about 1-2 jins (a half to one kilogram). ~

Miao Pleated Skirts

Miao women wear tubular skirts, girdle skirts, pleated skirts and many other kinds of skirts. The pleated skirt is the most characteristic. Miao pleated skirts have hundreds or even thousands of close, vertical pleats. They are beautiful and artistic, but complicated to make, and associated most with Miao women in western Hunan. It is said that Miao women generally wore tubular skirts in ancient times, but changed to pleated skirts to easily distinguish the Miao from other ethnic groups. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

Miao women wear tubular skirts, girdle skirts, pleated skirts and many other kinds of skirts. The pleated skirt is the most characteristic. Miao pleated skirts have hundreds or even thousands of close, vertical pleats. They are beautiful and artistic, but complicated to make, and associated most with Miao women in western Hunan. It is said that Miao women generally wore tubular skirts in ancient times, but changed to pleated skirts to easily distinguish the Miao from other ethnic groups. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

According to the legend "The Origin of Pleated Skirts" from the middle region of Guizhou: in ancient times, the skirts of Miao and Han were the same. In order to make them different, a mother and daughter decided to sew a special skirt to symbolize the Miaos. They thought for a long and hard time and were finally inspired by a colorful green flower they found on a mountain slope. They made a skirt with pleats resembling the flower and wore it a place where other Miao women threaded flower garlands. The Miao women applauded and praised the pleated skirt. They all learned to sew and wear pleated skirts, and the custom spread to other Miao villages, and women in different branches of the Miao began to wear pleated skirts of different length. ~

The pleated skirt of the Miao is requires great skill to make as the pleats are close and rich. Some even have thousands of pleats. The body of the skirt is straight vertically and sways back of forth horizontally. There are colorful designs and figures embroidered on the skirt. These vary from place to place. The pleated skirts in Huangping, Guizhou are usually made of narrow hand-woven dark purple cloth which the Miao women there weave and dye themselves. The skirt is composed of head, body and edge. Among these the edge is the most beautiful and important part. To make a skirt 1) these women put hand-woven cloth on a grassy area or a sunning mat, spray the juice of hyacinth bletilla on it and fold it into pleats of the same size. 2) Then they spray the juice again and finalize the design with white thread stringing the pleats together. 3) The edge is made of four lines of horizontal figures (from the bottom upward): the first line is " little humans figure"; the second line is" birds' wings figure" and the third and forth lines are " dragon figures". The first and second are embroidered lines, and the third and forth are woven lines. ~

Miaos' pleated skirts can be divided into three kinds according to the length: long, mid-length and short skirts. Long skirts reach the feet; mid-length skirts drop below knees; and short skirts reach the knees. A kind of short skirt worn by Miao women in Leishan, Guizhou is only about 20 centimeters long, and the people wearing it are called " short skirt Miao". Short skirts are often worn with trousers. There is a legend about the origin of short skirt in Leishan: in ancient times, there was a very handsome and brave Miao hunter. Once caught a very beautiful golden pheasant and gave the bird to his girlfriend, Abang. In order to express her deep affection to the young man, Abang wove a cloth stitched and embroidered with flowers and designs inspired by the golden pheasant. She then then made the cloth into a short skirt and decorated herself like a beautiful, golden pheasant. The hunter was impressed and enchanted. After that, other girls learned to make the embroidered short skirt and the design caught on Miao women in that area. ~

Image Sources: Nolls China website, San Francisco Museum, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China “, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Wikipedia, BBC, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022