MIAO AND HMONG

The Miao are a colorful and culturally- and historically-rich ethnic minority that lives primarily in southern China, Laos, Myanmar, northern Vietnam, and Thailand. Originally from China, the Miao are animists and ancestor worshipers and have traditionally lived in villages located at 3,000 to 6,000 feet. They live mostly in Guizhou, Yunnan, Guangxi, and Sichuan in southern China.

The Miao ((Pronounced mee-OW) are known in Southeast Asia as the Hmong (pronounced mung). They are ethnically different and linguistically distinct from the Chinese and the other ethnic groups in China and Southeast Asia. The Miao have very long history. Because they are scattered very widely, Miao in different places have quite different customs, and they go by many different names, The Miao can be quite different from one another. The difference between Miao groups is often as pronounced as between Miaos and non-Miaos.

Hmong means "free men." Miao means :weeds” or ‘sprouts.” The Chinese used to call them “man”, meaning “barbarians," The Laotians, Vietnamese and Thais call them the Meo, which means essentially the same thing as Miao.

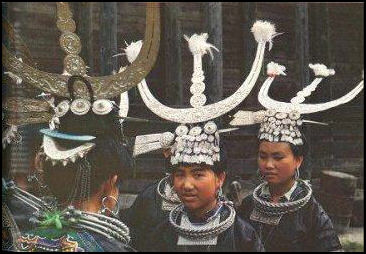

The Miao define themselves in many different ways, but Chinese often categorize them according to the region where they live and the color of the distinctive clothing the women wear. Hmong and Miao subgroups — Red Miao, White Miao (Striped Miao), Cowery Shell Miao, Flowery Miao, Black Miao, Green Miao (Blue Miao) — are in most cases named of the color of the woman's dress. The Miao in west Hunan are referred to as Red Miao, while those in south Sichuan are known as Green or Blue Miao. There are two main groups in Southeast Asia: the White Hmong and Green Hmong. See Clothing Under in MIAO CULTURE, MUSIC AND CLOTHES factsanddetails.com

See Separate Articles: MIAO IN GUIZHOU IN THE 1900s factsanddetails.com; GUIZHOU IN THE 1900s: BANDITS AND ROUGH TRAVEL factsanddetails.com MIAO MINORITY: SOCIETY, LIFE, MARRIAGE AND FARMING factsanddetails.com MIAO CULTURE, MUSIC AND CLOTHES factsanddetails.com ; MIAO AND DONG AREAS OF GUIZHOU PROVINCE factsanddetails.com GUIZHOU PROVINCE, THE GUIYANG AREA AND THE ETHNIC GROUPS THAT LIVE THERE factsanddetails.com ; HMONG MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION AND GROUPS factsanddetails.com; HMONG LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE, FARMING factsanddetails.com; HMONG IN AMERICA factsanddetails.com; HMONG, THE VIETNAM WAR, LAOS AND THAILAND factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia article ; Photos marlamallett.com Miao Language omniglot.com ; Book Chinese Minorities stanford.edu ; Chinese Government Law on Minorities china.org.cn ; Minority Rights minorityrights.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Ethnic China ethnic-china.com ;Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; China.org (government source) china.org.cn ; Paul Noll site: paulnoll.com ; Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China Books: Ethnic Groups in China, Du Roufu and Vincent F. Yip, Science Press, Beijing, 1993; An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China, Olson, James, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1998; “China's Minority Nationalities,” Great Wall Books, Beijing, 1984; “Weavers of Ethnic Culture: The Miaos” by Gu Wenfeng (Yunnan education publishing house, China, 1995)

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Hmong/Miao in Asia” by Nicholas Tapp, Jean Michaud, et al. Amazon.com; “Butterfly Mother: Miao (Hmong) Creation Epics from Guizhou” by Mark Bender Amazon.com; “The Art of Ethnography: A Chinese "Miao Album"” by David Deal, Laura Hostetler, et al. Amazon.com ; “Minority Rules: The Miao and the Feminine in China's Cultural Politics” by Louisa Schein Amazon.com; “Tourism and Prosperity in Miao Land: Power and Inequality in Rural Ethnic China’ by Xianghong Feng Amazon.com “Gathering Medicines: Nation and Knowledge in China’s Mountain South” by Judith Farquhar and Lili Lai Amazon.com; History “Amid the Clouds and Mist: China’s Colonization of Guizhou, 1200–1700" (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by John E. Herman Amazon.com; “Empire and Identity in Guizhou: Local Resistance to Qing Expansion” by Jodi L. Weinstein Amazon.com; “Narrating Southern Chinese Minority Nationalities: Politics, Disciplines, and Public History” by Guo Wu Amazon.com ; “Civil War in Guangxi: The Cultural Revolution on China's Southern Periphery” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com; Textiles, Clothes, Jewelry: “Miao's Attires” by Wan Zhixian, Yan Da, et al. Amazon.com; “Ethnic Miao Silver” by Yu Weiren and Wan Zhixian Amazon.com

Miao in China

The Miao are one of the largest minorities in China. They are widely distributed over Guizhou, Yunnan, Guangxi and Sichuan provinces, with a small number living on Hainan Island and in Guangdong Province and in southwest Hubei Province. Most of them live in tightly-knit communities, with a few living in areas inhabited by several other ethnic groups. Even though they have intermarried a great deal with the Chinese, they are shorter and their eyes and faces look different than those of Chinese. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, these disparate groups were given the standardized name: "Miao".

The Miao are one of the largest minorities in China. They are widely distributed over Guizhou, Yunnan, Guangxi and Sichuan provinces, with a small number living on Hainan Island and in Guangdong Province and in southwest Hubei Province. Most of them live in tightly-knit communities, with a few living in areas inhabited by several other ethnic groups. Even though they have intermarried a great deal with the Chinese, they are shorter and their eyes and faces look different than those of Chinese. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, these disparate groups were given the standardized name: "Miao".

The wide dispersion of the Miao makes it difficult to generalize about the places they live. Miao villages are found in valleys a few hundred meters above sea level as well at elevations of 1,400 meters or higher. Most are uplands people, living at elevations over 1,200 meters at some distance away from urban centers or the lowlands and river valleys where the Han are concentrated. Often, Miao upland villages and hamlets are interspersed with those of other minorities such as Yao, Dong, Zhuang, Yi, Hui, and Bouyei. [Source: Norma Diamond, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

The Miao live in over 700 counties, cities and and township in seven provinces of south China. Most Miao live in the autonomous prefectures and counties designated as Miao or part-Miao. Some live in villages within minzuxiang (minority townships), in areas that have a high concentration of minority peoples but not autonomous status, such as Zhaotong Prefecture in northeastern Yunnan. |The main Miao settlements are in the Southeastern Guizhou Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture, the Southern Guizhou Bouyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, the Southwestern Guizhou Bouyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, the Western Hunan Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, the Wenshan Zhuang and Miao Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan, and the Rongshui Miao Autonomous County in Guangxi Province. The Southeastern Guizhou Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture has the highest concentration of Miao. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

The Wuling and Miaoling mountain range in Guangxi Autonomous Region is home to nearly one-third of China's Miao people. On the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau and in some remote mountainous areas, Miao villages are comprised of a few families, and are scattered on mountain slopes and plains with easy access to transport links. Much of the Miao area is hilly or mountainous, and is drained by several big rivers. The weather is mild with a generous rainfall, and the area is rich in natural resources. Major crops include paddy rice, maize, potatoes, Chinese sorghum, beans, rape, peanuts, tobacco, ramie, sugar cane, cotton, oil-tea camellia and tung tree. Hainan Island is abundant in tropical fruits. [Source: China.org |]

Miao groups in China are quite diverse and they tend to be divided by language and clothing. Duyun is the home of the “Chicken Feather Miao.” In China, Guizhou Province is regarded as “the base of the Miao nationality.” Inside Guizhou, the majority of the Miao population resides in the Southeastern Guizhou Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture. Tai County has the highest concentration of Miao ethnicity at 97 percent and is referred to as “the number one county of the Miao nationality.” The remaining population is distributed in less concentrated numbers in other counties in Guizhou province. In southeastern Guizhou, the Miao population accounts for over 25 percent of the total Miao people in China. This subgroup tends to inhabit remote mountainous areas far away from the cities in tight-knit village networks. There, they seldom live in villages consisting of any nationality other than their own. Chinese and foreign ethnologists regard Guizhou as the best place to research the Miao, with the Taijiang region being the “brightest pearl” in regards to understanding the customs and culture of the group. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Miao Population

Thanks Joshua Project

There are an estimated 15 million to 16 million Miao and Hmong worldwide. The Hmong diaspora is scattered across the globe. They exist on five continents. Countries with significant populations in Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, France, Britain, Canada, Australia, and the United States. There are about 300,000 in Vietnam, 200,000 in Laos, 50,000 in Thailand and few thousand live in Burma near the Chinese border.

Miao are the fifth largest ethnic group and the fourth largest minority in China. They numbered 11,067,929 in 2020 and made up 0.79 percent of the total population of China in 2020 according to the 2020 Chinese census. Miao population in China in the past: 0.7072 percent of the total population; 9,426,007 in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census; 8,945,538 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 7,398,035 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 2,511,339 (0.43 percent of China’s population) were counted in 1953; 2,782,088 (0.40 percent of China’s population) were counted in 1964; and 5,017,260 (0.50 percent of China’s population) were, in 1982. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

Total fertility rate the Miao was 1.82 according to the 2010 census, compared to 1.14) for Han China and 1,6 for Tibetans. Large population jumps have been attributed to natural increase as of 1990 the Miao were not limited to one or two children as was the case with Han Chinese under the One-Child Policy and the recognition of additional population as Miao and better census procedures. |~|

In China, about half of all Miao live in Guizhou Province. About 20 percent are in Hunan, 13 percent are in Yunnan, 7 percent are in Sichuan, 6 percent are in Guangxi and 2 percent are in Hubei. The 50,000 or so in Hainan are known as Miao but are ethnically closer Yao and Li. Many Miao live in 14 autonomous prefectures and counties set up for them.

Origins of the Miao

The Miao have a very long history. Their legends claim that they lived along the Yellow River and Yangtze River valleys as early as 5,000 years ago. Later they migrated to the forests and mountains of southwest China. There they mostly lived in Guizhou Province.

It is believed that the ancestors of Miao may have been part of the Three South people (an ancient nationality) that evolved from the Zong people of the Zhou Dynasty. During the Qin and Han Dynasties (approximately 200 B.C. to A.D. 200), they mainly occupied Western Hunan and Eastern Guizhou Provinces and gradually moved and spread throughout the mountainous areas in Southwestern China. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Through legends and stories the Miao assert their lineage stems from the ancient Jiuli people. The Miao people in Sichuan, Guizhou, and Hunan Provinces believe Chi You, an ancient mythical half bull-half giant creature and leader of the Jiuli, is their ancestor. Thousands of years ago, the legend goes, the Jiuli tribe was forced to retreat from the lower reaches of the Yellow River to the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze being soundly defeated by the Chinese at the hands of very ancient legendary Yellow Emperor. From this defeat and exodus the "Three Miao" were gradually formed. By the 2nd century B.C., most of the Miao's ancestors had moved on to the Xiang River basin in southern China. \=/

Early Miao History

Some consider the Miao to be the original inhabitants of the Chinese heartland of eastern China, predating the Han Chinese. Some believe they originally came from the river valleys of what are now the Hunan and Jiangxi provinces of south-central China. Other believe they originated father north in the polar regions.The Miao were described in ancient Chinese chronicle as a rebellious people that were banished from the central plains around 2500 B.C. They were displaced by Han Chinese invaders from the north around 2000 B.C. and have been migrating southward and western to the mountains of southern China and Southeast Asia ever since.

There are some references to the Miao in Chinese records from 1300 to 200 B.C. According to ancient historical records the Miao settled in western Hunan and eastern Guizhou during the Qin and Han dynasties over 2,000 years ago. Often they ended up territories dominated by other non-Han-Chinese ethnic groups, who subjugated and even enslaved them. The Hmong were often leaders in rebellions against the Chinese. From around 2,000 years ago to around A.D. 1200 the ancestors of the Miao were grouped with other minorities and collectively referred to as southern barbarians (“Man”). The Miao were referred to as the Miao in Chinese documents of the Tang and Song period (A.D. 618-1279). After A.D. 1200 there are numerous reference to the Miao. Most of them are descriptions of Miao uprisings against the Chinese state.

According to the Chinese government: “Early Miao society went through a long primitive stage in which there were neither classes nor exploitation. Totem worship survived among Miao ancestors until the Jin Dynasty 1,600 years ago. By the Eastern Han Dynasty (A.D. 25-220), the ethnic minorities in the Wuxi area had begun farming, and had learned to weave with bark and dye with grass seeds, and trade on a barter basis had emerged. But productivity was still very low and tribal leaders and the common people remained equal in status. [Source: China.org |]

From their early days on, the Miao had a reputation for always being on the move. They primarily practiced slash-and-burn agriculture and had to move every few years to find new land. Families never lived in the same house more than five years. As the soil in one area became depleted, they would move away. It wasn’t until the middle of the twentieth century that many Miao groups settled in one place.

Early Encounters Between Chinese and Miao

Samuel R. Clarke wrote in “Among the Tribes of South-west China” in 1911: When the people now known as Chinese reached the regions which at present form the provinces of Shaanxi and Shanxi in north China, they found much land already occupied by tribes not unlike themselves. These tribes were doubtless the descendants of people who had, at an earlier date, migrated from the west. Those to the south were called Nan Man or Southern Barbarians. They were also called Miao. The character Miao, as written in the “ Book of History,'' means tender blades of grass or sprouts, and it is hard to decide whether the people were so named in consequence of the district they occupied, or whether the district took its name from the people. The word is evidently Chinese, and seems to be a natural term for all newcomers to apply to the aborigines, whom they regard as sons of the soil. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911). Clarke served as a missionary in China for 33 years, 20 of those in Guizhou]

When the Chinese first came upon the scene, the Nan Man or Miao were probably as numerous, if not more numerous than the new arrivals. The Chinese, however, were not only more civilised but under one government, whereas the Miao were divided under many local kings and rulers. The inevitable result followed. The Miao were gradually destroyed, or absorbed by the conquering race, or driven to the less desirable regions of the west and south-west. This process of absorption has been going on since the days of Yao and Shuen, 2356 B.C., and may be observed at the present time in the province of Guizhou. In that province many of the Chinese have Miao wives or concubines, and the children of such marriages always claim to be and are looked upon as Chinese.

In the “ Canon of Shuen “ it is recorded that Shuen drove the San Miao into San Wei. Whether San Miao was the name of one tribe or meant three tribes is not clear. San Wei was a district extending from what is now Kiukiang, in the province of Guangxi, to Yochow, at the mouth of the Tungting Lake in the province of Hunan. This was about 4000 years ago. Later on, as the Miao continued rebellious, Yii was sent, at the command of Shuen, to correct them. For reasons which do not appear, Yii sent back his army and determined to try the effect of moral suasion on these unmanageable people, and in seventy days the Prince of the Miao came to make his submission!

From that time forth the struggle has proceeded between the ever-encroaching Chinese and the Miao, in which struggle the more civilised and better organised Chinese have always, in the end, prevailed. About 800 B.C. Shuen Wang, one of the kings of the Chow dynasty, sent an expedition against them. Fang Shuh, who was the leader, proceeded with three thousand chariots as far as the present cities of Changsha and Changte in Hunan. Three mailed warriors rode in each chariot, and these, with other soldiers, made up a force of some thirty thousand men. The barbarians, alarmed at the news of recent Chinese victories over the Northern Tartars, and terrified by the , beating of drums and cymbals, submitted without resistance.

Battle Between the Chinese and Miao at Xiushan in 1795

During the reign of Qin Shi Huang, the Emperor who built the Great Wall and overthrew the feudal system of China (200 B.C.), cities were built in what are now the southern provinces of the Empire, and the whole of that country was brought under real or nominal subjection. The wilder west was, however, still unsubdued, and into these higher and less fertile regions many of the Miao withdrew.

Miao Migrations

The Miao are regarded as disciplined and have a long martial tradition and history of migration. Norma Diamond wrote: Chinese scholarship links the present-day Miao to tribal confederations that moved southward some 2,000 years ago from the plain between the Yellow River and the Yangtze toward the Dongting Lake area in northeastern Hunan Province. These became the San Miao mentioned in Han dynasty texts. Over the next thousand years, between the Han and the Song dynasties, these presumed ancestors of the Miao continued to migrate westward and southward, under pressure from expanding Han populations and the imperial armies. Chinese texts and Miao oral history establish that over those years the ancestors settled in western Hunan and Guizhou, with some moving south into Guangxi or west along the Wu River to southeastern Sichuan and into Yunnan. [Source: Norma Diamond, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

The period was marked by a number of uprisings and battles between Miao and the Han or local indigenous groups, recalled in the oral histories of local groups. Though the term "Miao" was sometimes used in Tang and Song histories, the more usual term was "Man," meaning "barbarians." Migration continued through the Yuan, Ming, and early Qing, with some groups moving into mainland Southeast Asia. The retreat from Han control brought some into territories controlled by the Yi in northeast Yunnan/northwest Guizhou.

In some cases their migrations have been as much as vertical — from the lowlands into the highlands — as horizontal across Asia. An old Miao saying goes: "Birds nest in trees, fish swim in rivers, Miao live in mountains." Depending on the terrain, the settled farming cited in Miao historical myths gave way to shifting slash-and-burn agriculture, facilitated by the introduction of the Irish potato and maize in the sixteenth century, and the adoption of high-altitude/cool-weather crops like barley, buckwheat, and oats. Farming was supplemented by forest hunting, fishing, gathering, and pastoralism.

Miao in Imperial China

In the third century A.D., the ancestors of the Miaos went west to present-day northwest Guizhou and south Sichuan along the Wujiang River. In the fifth century, some Miao groups moved to east Sichuan and west Guizhou. In the ninth century, some were taken to Yunnan as captives. In the 16th century, some Miaos settled on Hainan Island. As a result of these large-scale migrations over many centuries the Miaos became widely dispersed. Such a wide distribution and the influence of different environments has resulted in marked differences in dialect, names and clothes. Some Miao people from different areas have great difficulty in communicating with each other. Their art and festivals also differ between areas. [Source: China.org *|]

Miao Rebellion (1795-1806): Attack on the Rebel Nest and Beiqing and Balin

According to the Chinese government: “Miao society changed rapidly between the third and tenth centuries A.D. Communal clans linked by family relationships evolved into communal villages formed of different regions. Vestiges of the communal village remained in the Miao's political and economic organizations until liberation in 1949. Organizations known as Men Kuan in the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), and as Zai Kuan during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), were formed between several neighboring villages. Kuan leaders were elected by its members, who met regularly. Rules and regulations were formulated by all members to protect private property and maintain order. Anyone who violated the rules would be fined, expelled from the community or even executed. All villages in the same Kuan were dutybound to support one another, or else were punished according to the relevant rule. [Source: China.org |]

“By the end of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the Miaos had divided into different social classes. Communal leaders had authority over land, and frequent contacts with the Hans and the impact of their feudal economy gave impetus to the development of the Miao feudal-lord economy. The feudal lords began to call themselves "officials," and called serfs under their rule "field people." During the Song Dynasty (960-1279), some upper class Miaos were appointed prefectural governors by the imperial court, thus providing a political guarantee for the growth of the feudal economy. Under the rule of feudal lords, the ordinary people paid their rent in the form of unpaid service. The lords had supreme authority over them, and could punish them and bring them to trial at will. If feuds broke out between lords, the "field people" had to fight the battles. By this time, agriculture and handicrafts had been further developed. Grain was traded for salt between prefectures, and Xi cloth was sent as a tribute to the imperial court. High-quality iron swords, armor and crossbows came into use. By the end of the Song Dynasty, the Miaos in west Hunan had mastered the technique of iron mining and smelting. Textiles, notably batik, also flourished. Regular trade sprung up between the Miaos and Hans. |

Norma Diamond wrote: From Song on, in periods of relative peace, government control was exercised through the tusi system of indirect rule by appointed native headmen who collected taxes, organized corvée, and kept the peace. Miao filled this role in Hunan and eastern Guizhou, but farther west the rulers were often drawn from a hereditary Yi nobility, a system that lasted into the twentieth century. In Guizhou, some tusi claimed Han ancestry, but were probably drawn from the ranks of assimilated Bouyei, Dong, and Miao. Government documents refer to the "Sheng Miao" (raw Miao), meaning those living in areas beyond government control and not paying taxes or labor service to the state. In the sixteenth century, in the more pacified areas, the implementation of the policy of gaitu guiliu began the replacement of native rulers with regular civilian and military officials, a few of whom were drawn from assimilated minority families. Land became a commodity, creating both landlords and some freeholding peasants in the areas affected. In the Yunnan-Guizhou border area, the tusi system continued and Miao purchase of land and participation in local markets was restricted by law until the Republican period (1911-1949). [Source: Norma Diamond, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Miao Rebellions in the 1700s and 1800s

The Chinese were sometimes rattled by the threats posed by the Miao. Their major concern was that their rebelliousness might influence other groups to also rebel. The uprising often began as disputes over taxes and access to resources and sometimes ended with ethnic cleansing campaigns. In times of peace the Miao were largely governed through the tusi system.

Norma Diamond wrote: During the Qing, uprisings and military encounters escalated. There were major disturbances in western Hunan (1795-1806) and a continuous series of rebellions in Guizhou (1854-1872). Chinese policies toward the Miao shifted among assimilation, containment in "stockaded villages," dispersal, removal, and extermination. The frequent threat of "Miao rebellion" caused considerable anxiety to the state; in actuality, many of these uprisings included Bouyei, Dong, Hui, and other ethnic groups, including Han settlers and demobilized soldiers. At issue were heavy taxation, rising landlordism, rivalries over local resources, and official corruption.[Source: Norma Diamond, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Miao Rebellion (1795-1806): Victory over the Bandits at Huanghua

The Miao Rebellion of 1795–1806 was an anti-Qing uprising in Hunan and Guizhou provinces, during the reign of emperor Jiaqing. Ignited by tensions between local populations and Han Chinese immigrants, it was brutally suppressed and it served as a prelude to the much Miao Rebellion of 1854–73. The term "Miao" not only included descendants of today’s Miao but also other ethnic minorities. At that time “Miao” was a general term used by the Chinese to describe various aboriginal, mountain tribes of Guizhou and other south-western provinces of China. The tribes made up 40 to 60 percent of Guizhou’s population. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Han Chinese began migrating to southwest China in serious numbers beginning in 15th century. The most common method of Chinese rule in the provinces of Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi and Sichuan was through semi-independent local chieftains, called tusi, whose titles were bestowed by the Emperor, who demanding only taxes and peace in their territories. However, Han Chinese immigration was forcing the original inhabitants out of the best lands; Guizhou's territory, although sparsely populated, consists mainly of high mountains, which offer little arable land.The Chinese state "followed" the immigrants, establishing its structures, first military, then civil, and displacing semi-independent tusi with regular administration over time. This practice, called gaitu guilu, led to conflicts.

The uprising was one of the long series dating back to Ming dynasty's conquest of the area. Whenever tensions reached a critical point, the people rose in revolt. Each rebellion, bloodily put down, left simmering hatred, and problems which were rather suppressed than solved. Basic questions of misrule, official abuse, extortion, over-taxation and land-grab remained. Mass Chinese immigration put a strain on scarce resources, but officials preyed on rather than administer the population. The quality of the officialdom in Guizhou and neighbouring areas remained very low. Great uprisings took place in Ming times, and during Qing dynasty in 1735–36, 1796–1806, and last and the largest in 1854-1873. The rebellion of 1736 was met with harsh measures. After that things were was relatively calm but officials worried about unorthodox sects, whose teachings were embraced by both Han and Miao. In 1795, tensions reached a critical point and the Miao, under Shi Liudeng and Shi Sanbao, rebelled again

Hunan was the main area of fighting, with some taking place in Guizhou. The Qing dynasty sent banner troops, Green Standard battalions and mobilized local militias and self-defence units. The lands of rebellious Miao were confiscated, to punish them and to increase the power of state; this action, however, provoked further conflicts, because new Chinese landowners ruthlessly exploited their Miao tenants. On the pacified territories forts and military colonies were set up, and Miao and Chinese territories were separated by the wall with watchtowers. Still, it took eleven years to finally quell the rebellion. Military action was followed by the policy of forced assimilation: traditional dress and religious rites were forbidden and ethnic segregation policy enforced. There were also attempts at introducing Confucian education. Nevertheless, the deep causes of unrest remained unchanged and the tensions grew again, until they exploded in the largest of Miao uprisings of 1854. However, it should be noted that relatively few of Hunan Miao, "pacified" in 1795-1806, participated in the rebellions of the 1850s.

The Miao Rebellion of 1854–1873 was an uprising in Guizhou province and was one of many ethnic uprisings in China in the 19th century. The rebellion spanned the Xianfeng and Tongzhi periods of the Qing dynasty, and was eventually suppressed with military force. Estimates place the number of casualties as high as 4.9 million out of a total population of 7 million, though these figures are likely overstated. The rebellion stemmed from a variety of grievances, including long-standing ethnic tensions with Han Chinese, poor administration, grinding poverty and growing competition for arable land. The eruption of the Taiping Rebellion led the Qing government to increase taxation, and to simultaneously withdraw troops from the already restive region, thus allowing a rebellion to unfold.

See Miao TAIPING REBELLION factsanddetails.com; LEADERS OF THE TAIPING REBELLION AND THE IDEOLOGY BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com

Later Miao History

Miao hunters in the early 1900s

The last major Miao uprising was in 1856. After that time the Chinese discouraged Miao insurrections by displaying the severed heads of rebel leaders in baskets. The Miao remain bitter and still refer to the Chinese as "sons of dogs." One Miao elder said: “If you want to know the truth about our people, go ask the bear who is hurt why he defends himself, ask the dog who is kicked why he barks, ask the deer who is chased why he charges the mountains."

During the Republican period ((1911-1949), the Chinese government favored a policy of assimilation for the Miao and strongly discouraged expressions of ethnicity. One of the last Miao uprisings occurred in 1936 in western Hunan in opposition to Kuomintang (Republican) continuation of the tuntian system, which forced the peasants to open up new lands and grow crops for the state. [Source: Norma Diamond, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

In the early 19th century the Miao began migrating into Southeast Asia and Hainan Island (Chinese territory off coast of Vietnam) after they were forced off their homelands in the Chinese forests by the Chinese and pressured into assimilating and adopting the Chinese language. Later they migrated southward and settled in the mountains in Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia, where they raised live stock and grew rice and other crops. [Sources: Spencer Sherman, National Geographic, October 1988; W.E. Garret, National Geographic, January 1974]

On migrations of Miao-Hmong to Southeast Asia See HMONG MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Miao Under the Communist Chinese

Southwestern China came under Communist government control by 1951.Miao participated in land reform, collectivization, and the various national political campaigns. As of the 1990s, fourteen autonomous prefectures and counties were designated as Miao or part-Miao. Among the largest of these were the Qiandongnan Miao-Dong Autonomous Prefecture and Qiannan Bouyei-Miao Autonomous Prefecture established in Guizhou in 1956, the Wenshan Zhuang-Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Yunnan established in 1958, and the Chengbu Miao Autonomous Country in Hunan organized in 1956. Some of these have since changed their names. [Source: Norma Diamond, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Norma Diamond wrote: In the autonomous areas created beginning in 1952, the Miao were encouraged to revive and elaborate their costumes, music, and dance, while shedding "superstitious" or "harmful" customs. Some new technology and scientific knowledge was introduced, along with modern medicine and schooling. The Miao suffered considerably during the Cultural Revolution years, when expressions of ethnicity were again discouraged, but since 1979 the Miao have been promoted in the media and the government has encouraged tourism to the Miao areas of eastern and central Guizhou.

Today most Miao remain paddy-rice and dry rice farmers. There are also involved in forestry, animal husbandry, crafts, and fishing. high. According to the Chinese government: “Miao areas differ in their scale of economic and educational development. After 1951, a number of Miao autonomous divisions were established in Guizhou, Yunnan, Guangxi, Guangdong, and Hunan. Most of these autonomous divisions have taken the form of multiethnic autonomy, as the Miaos have for a long time lived with the Tujia, Bouyei, Dong, Zhuang, Li and Han peoples. In some Miao areas, before autonomous authorities were established, priority was given to such things as the election of delegates to the People's congress and the training and appointment of minority administrative staff. Now a large number of Miao people have been promoted to leading posts. In Northwest Guizhou Autonomous Prefecture alone, Miaos account for 68 per cent of the district and township officials. [Source: China.org |]

“Before 1949, textiles, iron forging, carpentry, masonry, pottery, alkali making and oil pressing were the only industries in the area. After the birth of the People’s Republic of China, many factories and hydroelectric stations were built. Now electricity is widely used for lighting, irrigation and food processing. In mountainous areas, the Miaos have built reservoirs, dug canals and created new farmland. They have also developed a diversified economy according to local conditions. As a result, grain production as well as oil, fiber and starch crops and medicinal herbs have all flourished. This has helped to open up new sources of raw materials and supplies for industry and commerce, and improved the Miao people's living standards. Sheep raising has a long history in Weining Autonomous County, Guizhou, where 265,000 hectares of grassland and trees provide an ideal grazing area. Herds have grown rapidly as a result of the introduction of improved breeds and better veterinary services. |

The construction of railways between Guiyang and Kunming, and between Hunan and Guizhou has boosted the development of the Miao areas along the routes. Before 1949, more than half the counties in Qiandongnan Autonomous Prefecture had no bus services. Cultural, educational and public health provisions have also expanded rapidly. In 1984, there already were 23,000 teachers in Qiandongnan alone, of whom over half were of the Miao or Dong minorities. They set up schools in mountainous areas and brought education to the formerly illiterate mountain villages. Before 1949, the incidence of malaria was as high as 95 per cent in Xinchi village in Ziyun County, Guizhou Province. But since liberation, the disease has been eradicated through massive health campaigns. This is giving rise to the rapid emergence of clean, hygienic and literate Miao villages.” |

Miao Language

Miao in

Chinese characters

The Miao language belongs to a western branch of the Miao-Yao language group of the Chinese-Tibetan language family. This group also includes such well-known languages as Hmu and Kho Xyong. Miao is a tonal language with eight tones and a complex phonology. Some linguists classify Miao-Yao languages as Sino-Tibetan languages; some don’t. Miao-Yao languages are a family of languages spoken mainly by hill tribes and ethnic groups that live in isolated areas scattered across southern China, Vietnam, Laos and Thailand.

There are five main Miao-Yao languages, many associated with the speaker’s clothing: Red Miao, White Miao (Striped Miao), Black Miao, Green Miao (Blue Miao) and Yao. Often the language of one group is unintelligible to members of other groups and is divided into a number of dialects. About half of all Miao speak Red Miao and Black Miao languages.

The Miao had no written language until the 1950s when the Chinese and Thais developed Thai-based and Chinese-based scripts for them. Christian missionaries gave them a Roman-based script and used it to translate the Bible. The Miao had traditionally passed on their culture orally and through the use of story clothes. The Miao believe they once had a written languages but it disappeared after their ancient books were eaten by horses while Miao warriors slept exhausted from fleeing China. The Miao writing has two styles: 1) the "old Miao writing" created at the beginning of the 20th century and 2) the "new Miao writing" created after the new China was founded in 1949.

In China, three Miao dialects are spoken: 1) the Western Hunan dialect (in the east), 2) the northern Guizhou dialect (in the middle) and 3) the Sichuan-Guizhou-Yunnan dialect (in the west). Each dialect has several sub-dialects and local dialects. Among the Miao in Guizhou, the language system is intricate, consisting of three wide spread dialects, numerous sub-dialects, and many localized dialects. The Eastern Guizhou dialect is exclusive to the Taijiang Miao nationality. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

In some places, people who call themselves Miao use the languages of other ethnic groups. In Chengbu and Suining in Hunan, Longsheng and Ziyuan in Guangxi and Jinping in Guizhou, about 100,000 Miao people speak a Chinese dialect. In Sangjiang in Guangxi, over 30,000 Miaos speak the Dong language, and on Hainan Island, more than 100,000 people speak the language of the Yaos. Due to their centuries of contacts with the Hans, many Miaos can also speak Chinese. [Source: China.org |]

The Miao have employed a naming system in which father's and son's names are linked. This system has traditionally appeared at the transition period from matrilineal clan system to patrilineal clan system.

Miao Religion

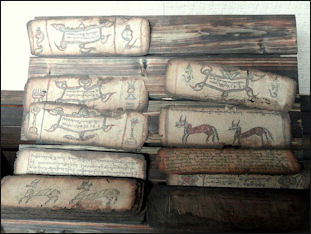

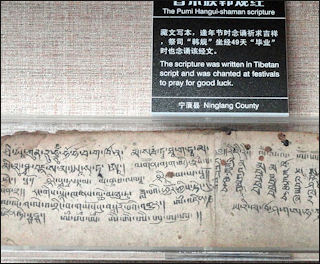

Manuscripts with shaman texts in

in the Yunnan Nationalities Museum The Miao are animists, shamanists and ancestor worshipers whose beliefs have been shaped somewhat by Chinese religions, namely Taoism and Buddhism, and, more recently in the case of some groups, Christianity. The Miao believe that supernatural powers are in everything around them and these powers can decide their fate. They also believe that everything that moves or grows has its own spirit. Within a house there are special altars for the spirits of sickness and wealth in the bedroom, the front room, and loft and near the house post and the two hearths.

Nicholas Tapp wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The Miao-Hmong otherworld is closely modeled on the Chinese otherworld, which represents an inversion of the classical Chinese bureaucracy. In former times, it is believed, humans and spirits could meet and talk with one another. Now that the material world of light and the spiritual world of darkness have become separated, particular techniques of communication with the otherworld are required. These techniques form the basis of Hmong religion, and are divided into domestic worship and shamanism. [Source: Nicholas Tapp, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Male household leaders are usually in charge of the domestic worship of ancestor spirits and household gods. Part time specialist act as priests, diviners and shaman. They don special clothes when the preside over rites and employ chants, prayers and songs they have memorized. They are paid in food for their services. Shaman are generally called upon on cure illnesses by bringing back lost souls. They play a key role in funeral rites and are called upon to explain misfortunes and preside over rites that protect households and villages. |~|

Miao worship the sun, moon, thunder, lightning, rivers, large trees, fire, and some animals. They also believe the spirits of the dead become ghosts that may haunt their families and animals, make them sick, or even kill them. Miao spirits are thought to live in high concentrations in places like sacred groves, caves, stones, wells and bridges. Household ancestor spirits are distinguished from spirits called up by shaman. The spirits that protect homes and villages are sometimes thought of as dragons.

Shamans help people to communicate with ghosts and spirits. The Miao also worship their ancestors. According to the Chinese government: “The Miaos used to believe in many gods, and some of their superstitious rituals were very expensive. In west Hunan and northeast Guizhou, for instance, prayers for children or for the cure of an illness were accompanied by the slaughter of two grown oxen as sacrifices. Feasts would then be held for all the relatives for three to five days. [Source: China.org |]

See MIAO IN GUIZHOU IN THE 1900s factsanddetails.com; On the religion of Hmong to Southeast Asia See HMONG MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com ; Miao Creation Myth, See Literature Under MIAO CULTURE, MUSIC AND CLOTHES factsanddetails.com

Miao Funerals

Manuscripts with shaman texts in

in the Yunnan Nationalities Museum After death, the Miao believe, the soul divides into three parts: one remains in the grave, a second joins his or her ancestor in the next world and the third returns to protect the home as an ancestor spirit. The dead have traditionally been buried or cremated by lighting branches piled on top of the body. Funerals generally last a minimum of three days and are attended by all male kin within the household of the deceased. The ceremonies are often wailing affairs with mournful songs played by reed pipes to guide the dead on his or her journey to the other world. Cattle are sacrificed and the dead are buried in a place with auspicious feng shui.

A shaman often presides over the funeral, singing mournful songs, blesses his or her the children, and tells the dead person how to join his or her ancestors. Funerals may be presided over by ritual specialists but shaman are preferred because they are more skilled in making sure the soul of the deceased is given a proper send off to the other world and doesn’t become a malevolent spirit.

On the third day after the burial the grave is renovated. On the 13th day after death a ceremony is held for the ancestral soul so it will protect the household. A final memorial service is held a year after death. Later the deceased spirts may be invoked to help cure illnesses or misfortunes. When an ancestor soul returns to its village it must collect its placenta which has been buried beneath his house. This journey is described in funeral songs in which parallels are drawn between its journey and the journey of the Miao out of China.

See Separate Article MIAO IN GUIZHOU IN THE 1900s factsanddetails.com

Miao Festivals

Many Miao groups have their own festivals and ceremonies, which vary from village to village. Many also celebrate Han Chinese holidays. Some celebrate the new year according to Han Chinese calendar Others celebrate it in the 10th lunar month following the harvest. Other important festivals include the Dragon Boat festival, the Mountain Flower festival, which are important in bring in young couples together, and Drum Society festivals, which are held only in some years to honor ancestors. [Source: Norma Diamond, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

There are many Miao festivals, such as the Miao New Year, the New Product Eating Festival, the Festival of Eating Bulls' Internal Organs, the Eighth of April, the Reed-Pipe Festival, the Dragon Boat Festival, Stepping Flower Hill, Singing Gathering in the Pure Brightness, Striking Drums festival, Horse Fighting festival, Slope-Climbing Festival and Eating "Sisters' Rice" Almost all types of festivals include as religion activities, farm work, commemoration, trade and socializing. Entertainment activities include singing in antiphonal style, dancing to reed pipes, horse racing, horse fighting, bullfights, cockfights, knife-pole climbing and swinging. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

Different Miao communities celebrate different festivals. Even the same festivals may fall on different dates. In southeast Guizhou and Rongshui County in Guangxi, the Miao New Year festival is celebrated on "Rabbit Day" or "Ox Day" on the lunar calendar. The festivities include beating drums, dancing to the music of a lusheng (a wind instrument), horse racing and bull-fighting. In counties near Guiyang, people dressed in their holiday best gather at the city's largest fountain on the 8th day of the forth lunar month to play lusheng and flute and sing of the legendary hero, Yanu. [Source: China.org |]

In many areas, the Miaos have Dragon Boat festivals and Flower Mountain festivals (5th day of the fifth lunar month), Tasting New Rice festivals (between the sixth and seventh lunar month), Pure Brightness festivals and the Beginning of Autumn festivals. In Yunnan, "Stepping over Flower Mountains" is a popular festivity for the Miaos. Childless couples use the occasion to repeat vows to the god of fertility. They provide wine for young people, who sing and dance under a pine tree, on which hangs a bottle of wine. Young men and women may fall in love on this occasion, and this, it is hoped, will help bring children to the childless couples. The Lusheng Festival is popular throughout Guizhou, Yunnan, and Sichuan provinces. The Lusheng Festival in Kaili, the famous tourist hub in Guizhou province, is considered to be one of the grandest celebrations of the Miao.

Sisters Festival (San Yue San) is a three day festival celebrated on the 14th to the 16th day of the 3rd lunar month (usually late March, Early April) by the Miao as well as Li, Zhuang, Dong, Yao, She, Mulao and Geleo minorities in China's southern and central provinces. Also called Valentines’s Day of the Miao, or Venus Day, it is a time when boyfriends and girlfriends are chosen and villages celebrate the occasion with singing, dancing, archery, wrestling, playing on swings, tug of wars, pole climbing and other activities. The Sisters' Meals festival is celebrated by the Miao people in Guizhou province, especially in Taijiang and Jianhe Counties along the banks of the Qingshui River. It has been called the oldest “Asian Valentine’s Day” and “Festival Hidden in Flowers”. During the festival, young women invite their boyfriends to have “Sister Meal” together and beat on drums, sing in antiphonal styles, exchange gifts, and even decide when they will get married.

The Dong and Miao celebrate the first day of the festival by eating and drinking milky white wine. On the second day girls give baskets of shrimp and fish to the boys they fancy. On the third day everyone meets in the town square to participate in "drum treading" and "reed-pipe" dances. On the night of the third day girls dress up in their most beautiful tribal costumes and go upstairs in their bamboo houses to sing to the boys who are waiting downstairs. Boys then follow the girls to the gate of the bamboo houses and sing their reply. All of the minorities perform the Money Bell and Double Daggers Dance. In this dance one man holds two daggers in his hand. Another man holds a money bell. The man with the daggers tries to stab the man with the money bell, who in turn tries to run away.

See Separate Article MIAO IN GUIZHOU IN THE 1900s factsanddetails.com

Miao New Year

The Miao New Year used to celebrated on the first four days of the tenth lunar month, which usually falls in December. but now it is generally held around the same time as Chinese New Year in February. It is the biggest event of the year. New clothes are put on, feasts are held, antiphonal songs are sung by courting couples, courting games are played, and ceremonies are held to honor household and ancestral spirits. Each household sacrifices domestic animals and holds a feast. Weddings are often held. Some villages stage bullfights. Other have cockfights.

The Miao New Year is main traditional festival of the Miao, but the time of celebration is different in different places. The "Guizhou Record" written by Guo Zizhang in the Ming Dynasty says:" The beginning of a new year is in the last three months in winter, and people celebrate in different months." The three months in winter refers to the tenth, eleventh and twelfth months of the Chinese lunar year. Today, Miao in most regions celebrate new year in the first month of the lunar year (late January or February), more or less the same as Han Chinese. Only Miao in the Southeastern Guizhou and part of Guangxi follow the old tradition and spend the new year in the Bull (one of the twelve symbolic animals and is called "Chou" in Chinese) day, the Hare (called "Mao" in Chinese) day, the Dragon (called "Chen" in Chinese) day during the tenth, eleventh and twelfth months of the lunar year (November through January). [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

The Miao New Year has traditionally been a harvest festival. Though the of time of celebration is different among different Miao groups, the content of the festival is generally the same among all Miao people. in different regions. In the days ahead of New Year, families do cleaning, butcher chicken and pigs, make rice cakes and rice wine and buys special things for the new year. On the New Year's Eve, families worship gods and offer sacrifices to ancestors, praying for an abundant harvest of all food crops and safety of people and domestic animals. Family members gather for a large feast, with special New Year foods. On New Year’s Day, people visit relatives and friends, wishing them a happy new year. Young people wear their best clothes and take part in all kinds of activities such as reed-pipe dancing, the beating wooden drums, bullfights, horse races and antiphonal singing (alternate singing by two choirs or singers). Miao villages are filled with sound of firecrackers and reed-pipes. ~

According to Miao custom, the tenth lunar month is the beginning of a new year. The exact date varies each year and is only disclosed one or two months in advance. The celebration of the Miao New Year in Leishan, Guizhou Province is the grandest among Miao festivities. It has become a tourist attraction as well as a gathering for Miao and otehr ethnic groups. Activities include the festival parade featuring Miao girls and women in silver-laden traditional Miao dress, the traditional music of the Lusheng (a kind of musical instrument made of bamboo), bullfights, horse racing, and much singing and dancing. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

Image Sources: Nolls China website, San Francisco Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Wikipedia, BBCand various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022