LAHU ETHNIC GROUP

The Lahus are a fairly large ethnic minority that lives in southwest China, northern Thailand, northern Laos, northern Vietnam and eastern Myanmar. Traditionally a semi-nomadic people, they reside in villages at an elevation of 1,000 meters or more, have a reputation of being easy going and friendly, and have traditionally grown rice and corn for food and, for a time, opium as a cash crop.

The Lahu are also known as Co Sung, Co Xung, Guozhou, Kha Quy, Khu Xung, Kucong, Kwi, Laho, Lohei and Mussur. Lahu is what the Lahu call themselves. Its origin and original meaning is not known There are several theories on the origin of their name; most of them make reference to their relationship with tigers. Some scholars translate their name as "those who adore the tiger", other "those who roast the tiger" and other "those who hunt the tiger."There are several Lahu subgroups. The two most important are the Lahu Na (Black Lahu) and Lahu Shi (Yellow Lahu). Other important subgroups include the Lahu Hpe (White Lahu) and Lahu Na (Black Lahu). [Source: Anthony R. Walker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Lahu are one of the most interesting ethnic groups of Southeast Asia in that still retain much of their traditional cultural, social and religious life and that gender equality still hold a high place in Lahu society. The Lahu tend to live in remote, isolated areas which helps explain why their culture has remained relatively untouched by the outside world. They speak a Sino-Tibetan language. Many speak Han and Dai languages.

About two thirds of the Lahu live in the the mountains around the Mekong (Lancang) River in the Lancang Lahu Autonomous County and Menglian Dai and Lahu Autonomous County in southwestern Yunnan Province in China About two thirds live of the Lahu in China live in Simao Prefecture, most of them in the Lancang Lahu Autonomous County, a quarter are on the Lincang Region and six percent in Shuangjiang County and 7 percent in Menglian County. Others live in counties along the Lancang River. Some are also scattered in Dai Autonomous Prefecture of Xishuangbanna and Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture of Honghe, and also Yuxi. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

The Lahu people also inhabit the hilly regions of the eastern parts of Myanmar and northern parts of Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam. The largest of the four Lahu tribes in Thailand, the Lahu Nyi subgroup, lives in a triangular area between Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai and Mae Hong Son.

The subtropical hilly areas along the Lancang River where the Lahu people in China live are fertile, suitable for planting rice paddy, dry rice, maize, buckwheat as well as tea, tobacco, and sisal hemp. There are China fir and pine, camphor and nanmu trees in the dense forests, which are the habitat of such animals as red deer, muntjacs, wild oxen, bears and peacocks. Found here are also valuable medicinal herbs like pseudo-ginseng and devil pepper. Mineral resources in the area include iron, copper, lead, aluminum, coal, silver, mica and tungsten. [Source: China.org |]

See Separate Article: LAHU LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Merit and the Millennium: Routine and Crisis in the Ritual Lives of the Lahu People” by Anthony R. Walker Amazon.com; “To the Mountain Tops: A Sojourn Among the Lahu of Asia” by Harold Mason Young Amazon.com; “Peoples of the Greater Mekong: the Ethnic Minorities” by Jim Goodman and Jaffee Yeow Fei Yee Amazon.com ; “The Lahu Minority in Southwest China: A Response to Ethnic Marginalization on the Frontier” by Jianxiong Ma Amazon.com “Lonely Planet Hill Tribes Phrasebook & Dictionary” by David Bradley , Christopher Court, et al. (2019) Amazon.com; “English-Lahu Lexicon” by James A. Matisoff Amazon.com; “Fleeing One Homeland and Adopting Another: The Construction of State Identity in a Northern Thailand Village” by Zhang Jinpeng Amazon.com; “Minority Cultures of Laos: Kammu, Lua', Lahu, Hmong, and Iu-Mien” by Judy Lewis (1992) Amazon.com Culture: Love Through Reed-Pipe Wind and Mouth-String: The Lahus by Xiao Gen, Yunnan Education Publishing House, 1995; Amazon.com; “Chopsticks Only Work in Pairs: Gender Unity and Gender Equality Among the Lahu of Southwestern China” by Du Shanshan, Columbia University Press. 2002. Amazon.com; “Mvuh Hpa Mi Hpa / Creating Heaven, Creating Earth: An Epic Myth of the Lahu People in Yunnan” by Anthony R. Walker Amazon.com;

Lahu Population and Groups

There are around 850,000 Lahu with around 500,000 in China and 170,000 in Southeast Asia, with around 100, 000 in Myanmar; 60,000 in Thailand, 5,000 in Laos and 4,000 in Vietnam. The 1990 census counted 64,000 Lahu in 290 villages in Thailand.

Lahu are the 24th largest ethnic group and the 23rd largest minority in China. They numbered 485,966 and made up 0.04 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Lahu populations in China in the past: 453,765 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 411,476 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 139,060 were counted in 1953; 191,241 were counted in 1964; and 320,350 were, in 1982. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia; Ethnic China *]

Lancang Lahu Autonomous Count

By some reckonings there are four Lahu branches: Lahuna (black Lahu), Lahuxi (or Lahu shi yellow Lahu), Lahu nyi and Lahu shehleh. All are remarkably similar despite being dispersed over such a large area. Officially the Kucong are considered to be a branch of the Lahu but this designation seems to be based more on the unwillingness of Chinese government to recognize too many minorities than similarities between the Lahu and Kucong. The culture, mythology, history, language, customs and lifestyle of the Kucong are different from that of the Lahuxi who live near them. In addition DNA tests indicate they are more closely related to Miao peoples than the Lahu. *\

The Lahu are incredibly diverse, including recently-transformed forest-dwelling hunters and gatherers as well slash-and-burn agriculturalists and paddy rice farmers. The two most important subdivisions are the Lahu Na (Black Lahu) and Lahu Shi (Yellow Lahu; called "Mussur Kwi" or just "Kwi" by the Shan). Lahu Hpu (White) live mainly in Yunnan. The Lahu Nyi (Red) are found in Myanmar's Shan State and in north Thailand. Yunnan's Kucong also have Black and Yellow divisions; the Black Kucong reportedly call themselves "Guozhou" but are termed "Lahu Na" by their Lahu Shi neighbors, and the Yellow Kucong call themselves "Lahu Shi." Ethnic identification by color labels is widespread in Southeast Asia. [Source: Anthony R. Walker , “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Origin of the Lahu

The Lahu ethnic minority has a long history. They are believed to be related to the Qiang and are one of the first ethnic groups to be chronicled in the Chinese historical record. They were referred to in the 12th century B.C. and originated from the western plains near the mountains in Gansu where the Qiang lived. The Qiang gave birth to the Lo-Los, a tribe which once had a number of independent kingdoms in the eastern Tibet and the Sichuan region of China. Some anthropologists believe the ancestors of the Akha, Lisu and Lahu descended from the Tibetan highlands in the second century B.C. after some of them lost their ability to deal with the harsh cold. [Source: Anthony R. Walker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: Linguistic analysis suggests that the Lahu descend from the old Qiang that lived in Northwest China in times of the first Chinese dynasties. Legends collected in recent times make us think that in remote times the Lahu inhabited the loess plateaus of the basin of the Yellow river. In those remote times the Lahu society was a matriarchy. More than 3,000 years ago, war and worsening climatic conditions provoked a first migration that led them to the shores of Qinghai Lake. From where moved centuries later to the south of Qinghai Province, until they reached the present Yushu Prefecture. [Source: Ethnic China *]

“Most of the books dealing with the history of the Lahu affirm that their origin lies in the present Qinghai province where their forefathers were a branch of the Di-Qiang peoples. They usually say also that wars and conflicts started them on a long migration that led them to the region of Erhai Lake first and to their present territory in the last term.” But relatively recent DNA analysis links the Lahu with Yunnan local populations not with Di-Qiang peoples or their descendants. [Source: Ma Jianxiong. “Local Knowledge Constructed by the State - Reinterpreting Myths and Imagining the Migration History of the Lahu in Yunnan, Southwest China.” Asian Ethnology Volume 68, Number 1 o 2009, 111-129; Ethnic China *]

This contradiction is the starting point of for research by Ma Jianxiong into the way "The history of the Lahu" was created, the theoretic framework in which it was inscribed, and the political reasons fore backing up the historical status quo. Ma found the linguistic studies that put the Lahu in Qinghai were not always done in scientific way and places mentioned in the Lahu Creation Myth and other songs sung in Lahu funerals that were labeled as places in Qinghai province but also could be places further south. In his own fieldwork among the Lahu, Ma Jianxiong discovered that not all the Lahu kept the same mythical tradition, that not all the Lahu agreed with the official interpretation givens to the place names of their myths, and that the official history of Lahu came into existence only in recent decades after it was spoon-fed by the Chinese government to the Lahu and researchers studying the Lahu. *\

Early History and Migration of the Lahu

Hill tribe migrations

The "ancient Qiang” lived in Qinghai, Gansu and Sichuan in ancient times and migrated southward into Yunnan and the Central South peninsula. There are several branches of Lahu, such as "Lahuna (black Lahu)," "Lahuxi (yellow Lahu)," and "Lahupu (white Lahu)". In history, they had names like "Shizong," "Yeguzong," "Kucong," "Luohei," "Mocha," "Mucha," and "Mushe" in different times. Legend says that the forbears of the Lahu people, who were hunters, began migrating southward to lush grassland which they discovered while pursuing a red deer. Possessing characteristics of both northern nomads and southern farmers, they lived a nomadic life in the beginning and gradually moved southward, and finally settled near Lancang (upper Mekong) River.

Some scholars believe the Lahu moved southward during the Warring States Period (475 -221 B.C.) and settled in Yunnan Province at that time. There, the Lahu came under the control of Yi tribes. When the Yi taxes became too heavy, the Lahu revolted and migrated. The Lahu also launched military operations in order to expand their territory and subjugated other ethnic groups.

Some scholars hold that during the Western Han Dynasty more than 2,000 years ago, the "Kunmings," the nomadic tribe living in the Erhai area in western Yunnan, might be the forbears of certain ethnic groups, including the Lahus. Historical records describe the Kunmings as still living "without common rulers" and belonged to different clans engaged in hunting. The Lahu people once were known for their skill at hunting tigers. They roved over the lush slopes of the towering Ailao and Wuliang mountains. [Source: China.org |]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote “It is believed that in the 7th century two Lahu political entities existed in southeast Qinghai: The Supi Kingdom and the Daomi Kingdom. These two kingdoms are believed to be the Women's Kingdoms, described in early Tang dynasty documents of that area. Both kingdoms were conquered by the Tubo dynasty of the Tibetans in the 7th century. After their defeat at the hands of the Tibetans, the Lahu migrated towards the south, settling down in the border between Sichuan and Yunnan provinces. The Lahu maintained good relationships with the Nanzhao Kingdom, as well as with the Dali Kingdom. Later difference between Dali and the Lahu provoked armed conflicts and a new migration by the Lahu.

Lahu in the Imperial Chinese Era

By the A.D. 3rd century the ancestors of the Lahu reached to the valleys of China's Yunnan province and established themselves around Dali and Kunming.. Between the A.D. 5th century and 10th century they emerged as a distinct ethnic and were famous in China for being tiger hunters. According to Chinese sources, the Lahu began migrating southward in the 10th century as two distinct groups: the Lahu Na (Black Lahu) headed in a westerly direction while the Lahu Hpe (White Lahu) took a more easterly route. [Source: Anthony R. Walker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

At the of Song Dynasty, there were at least three large-scale Lahu migrations. The constant migrations caused the Lahu to form two major groups: those on the east and west of Lancang River. The conquest of the Dali Kingdom by Kublai Khan’s Mongol-Chinese forces in 1253 caused disruptions for all peoples in Yunnan. The Lahu began a new wave new migration, with going some to the east and others to the west. The two main branches of the Lahu—the Lahuna who went to the west and the Lahuxi who migrated to the east—are the result of this migration. The long separation between the Lahuxi and the Lahuna created important linguistic and cultural differences among them. Their histories also separated. [Source: Ethnic China *]

Lahu flute players

It was until Qing Dynasty that the Lahu finally settled in the areas of China where they live today, but even after that there were still some minor migrations that included migrations to Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and some other countries. The Lahuxi migrated east until they reached the territory of the Dai and fell under the nominal dominance of the Tusi Dai. The Lahuxi of Lincang rebelled numerous times in the 15th and 16th centuries against the Dai but were ultimately defeated. Defeated warriors and their families escaped to remote Shuanjiang, Gengma and Cangyuan districts, where they are still living nowadays. The Lahuna went to the basin of the Lancang River (Upper Mekong River). That region was known as the "river of the Lahu" for some time. *\

According to the Chinese government: “In the 8th century, after the rise of the Nanzhao regime in Yunnan, the Lahu people were compelled to move south. By no later than the beginning of the 18th century they already had settled in their present-day places. Influenced by the feudal production methods of neighboring Han and Dai peoples, they turned to agriculture. With economic development, they gradually passed into a feudal system, and their life style and customs were more or less influenced by the Hans and Dais.” [Source: China.org |]

The Lahu fell into two categories: -- Feudal landlord economy, which was prevalent among the Lahus in Lancang County as well as among those in Shuangjiang, Lincang, Jinggu, Zhenyuan, Yuanjiang and Mojiang counties, who accounted for one half of the total Lahu population in these areas. Compared with the other Lahu areas, economic development in these areas was faster. Dai chieftain-dominated feudal manorial economy having remnants of primitive communes, which was prevalent in southwestern Lancang, Menglian, Gengma, Ximeng, Cangyuan and Xishuangbanna, where another half of the Lahu population lived. The Lahus led a poor life and their production was backward under the rule of Dai chieftains and the exploitation by Han landlords and merchants. One of the ways in which the Dai chieftains ruled and exploited the Lahu peasants was through establishing the tribute-paying system. This made the peasants subordinate to them. Dai lords also reduced Lahu peasants to the status of serfs who were required to do such jobs for the chieftains as husking grain and clearing night soil and manure. Remnants of the primitive communal system included mutual aid in production, common ownership of land and matriarchal clan system.” |

Modern History of the Lahu

Eventually many of the Lahu come under the control of Tai overlords, whose leadership was recognized by imperial China through the tusi (native chief) system. Between the 18th and early 20th the Lahu rebelled periodically but their crossbows and poison-tipped arrows were no match for the Chinese armies and the rebellion were always put down. During this period some Lahu migrated into Burma and Laos and were were well entrenched in the Burmese Shan States by the 1830s and in Laos by the 1850s. They probably began moving into north Thailand in the 1870s or 1880s.

The history of the Lahuxi in the 18th and 19th centuries was defined by continuous uprisings against the authority of the local Dai tusi chiefs. There were more than 20 uprisings of varying duration and intensity. During the first hundred years of this period of rebellions, the conflicts were mostly between the Dai overlords and oppressed Lahu. During the second hundred years the conflict was also the result of inequalities among the Lahus, varying degrees of collaboration eith the Dai and the emergence of powerful Lahu chiefs that shared the same economic interests as Tusi Dai and sometimes enslaved fellow Lahu and other ethnic groups. Rebellions during this period had a mixed ethnic and social character. As for the Lahuna, they were isolated in remote mountains. They generally avoided conflicts and kept their social structure intact until the end of the imperial era.

After 1912, the republican government's desire to control minorities in border areas lead to more of a Chinese presence in Lahuna areas . With the arrival of the Communist Chinese in the 1950s, traditional Lahu was greatly undermined. The Lahu were grouped in villages, communes or production teams. In recent centuries Lahu have mostly lived in mountainous areas, their villages interspersed with those of other ethnic groups, notably Wa and Hani (Akha) in the south and Yi in the north, but also many others. The rich alluvial valleys below their mountain homes have been controlled mostly by Tai peoples. Han Chinese settlers in southern Yunnan have tended to occupy lands in the foothills, above the valley bottoms but below the elevations favored by the true hill peoples. Lahu culture has been greatly influenced by its neighbors, particularly the Tai and Han Chinese.

Kucong: Traditional Lahu Hunter-Gatherers

The Kucong is a group that some consider branch of the Lahu and others consider a distinct ethnic group.There are around 80,000 of them in Thailand, China, Myanmar, Vietnam, and Laos, with about 15,000 to 20,000 members living in Zhengyuan and Jinping counties in Yunnan Province. For a long time they lived in such isolation that they were considered "invisible people". Even when they traded for necessities such as salt, clothes and metals, they didn't let the traders see them. [Source: Lin Zhenyu, “Dramatic changes for the Kucong”. In “China's Minority Nationalities,” Great Wall Books, Beijing, 1984; Ethnic China *]

The Kucong are one of the poorest groups in China. Until the 1950s they lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers in the forests of the Ailaoshan Mountains. Lin Zhenyu wrote in his article “Dramatic changes for the Kucongs” in the book “China's Minority Nationalities”: "They moved from one place to another in the forest, hunting, collecting wild fruits and raising some food by the slash-and-burn method...Their main weapon was the bow and arrow. When a boy was four or five, his parents would make a bow for him. He carried one the rest of his life. Even after his death, it was buried with him...Their shelters were merely three branches set in the ground and covered with plantain leaves … cooking vessels were the hollow sections of bamboo...The economic life of the Kucong was based on primitive equalitarianism. They shared the fruits of their labor equally."

When the Kucong traded they usually placed some medicinal grasses or mushrooms from the forest, things wanted by their neighbors, on the edge of the road. When somebody happened by and noticed them, he knew that the Kucong wanted to trade. If he wanted the items or knew someone who did, they could take the products from the forest, and leave a knife, a shirt or a small packet of salt. The Kucong, hidden in the forest, watched to see of something was traded.

The staple food of the Kucong is corn. They usually cook it with some vegetables and meat, if possible. Sometimes they roast it directly on the fire, cook cooking inside bamboo tubes or wrapped in banana leaves. Sometimes they place the corn and some water on a leaf, and cover it with more leaves before they put it on the fire. Vegetables or meat are cooked the same way, without adding water. They have traditionally added little salt because it was very scarce and difficult to get. Once the food is cooked, they place it on banana leaves and use chopsticks to eat it. *\

The houses of the Kucong are small and narrow, usually are only one meter high. The structure is made of wood or bamboo, with a roof formed with banana leaves or bamboo leaves. As these leaves wither very quickly, they need to be changed every one or two months. Their houses consist of a single room without divisions. There is a fire is in the center, around which the whole family sleeps, as well as its dogs, hens and pigs. That only room is usually very dark because there are no windows. The Kucong traditionally haven’t had blankets. At night they cover themselves with some grasses or banana leaves. *\

After 1949, some teams were sent to find the Kucong and settle them outside the forest. For some time these teams were unable to track down the 2,500 or so Kucong that existed at that time. Finally they were found and captured and forced to live in villages; but they never adapted to the farmers life. Today, they still keep a semi-nomadic existence, living mainly from hunting and gathering; and government subsidies.

Lahu Language

Lahu in

Chinese characters The Lahu and Lisu speak a language in the Central Loloish (or Yi) branch of the Lolo-Burmese subgroup of the Tibetan-Burmese branch of Sino-Tibetan languages. The Akha speak a Southern Loloish language. The Lahu language has two main dialects: Lahuna and Lahuxi, which are mutually intelligible. There are other dialects spoken by a minor number of Lahu. Most Lahus also speak Chinese and the language of the Dais.

The Lahu have no written language of their own. In the past the custom of passing messages by wood-carving was prevalent.They used to use notched sticks with chicken feathers attached to them to communicate simple messages. The Lahu say they once had an ancient language written on rice cakes by a group of ancient scholars but the language disappeared when the scholars became hungry and ate the cakes. Every new year Lahus eat rice-sesame cakes to remind them that their traditions can be found in their spiritual gastrointestinal track.

The Thais, Chinese and missionaries developed Roman-based, Thai-based and Chinese-based scripts for the Lahu language. Christian missionaries developed a Latin alphabetic system for their language in the beginning of the 20th century. It was not widely adopted. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Chinese developed script that became the Lahu’s formal written language but that was never really embraced either.

Lahu Religion

Some Lahus are Buddhists and many Lahus are Christians. About 40 percent of the Lahus in Thailand are Baptists. Many live in villages named after places in the Bible. Theravada Buddhism was introduced by their Tai neighbors during the early eighteenth century. Mahayana Buddhism was brought by the Han Chinese. Protestant and Roman Catholic Christianity were introduced, in that order, by Western missionaries beginning in the 1890s. Even so traditional animist beliefs remain strong. The Lahu have a supreme deity called Geusha. Among the important gods are the creator Sky Ghost and his female counterpart Mother Aima. Christians have absorbed these gods into the Christian schema.

In the early Qing Dynasty, Buddhism was introduced into Lahu areas from Dali by Buddhist monks. These Han and Bai monks opposed the Qing government and played an important part in mobilizing the Lahu and pther groups in revolts against the Qing. According to Chinese government: “In Shuangjiang and Lancang counties, religion had come to merge with politics. Military suppression by the Qing government and defeat of the peasant uprisings led to the disintegration of local Buddhist bodies.” [Source: China.org |]

In the early Qing Dynasty, Buddhism was introduced into Lahu areas from Dali by Buddhist monks. These Han and Bai monks opposed the Qing government and played an important part in mobilizing the Lahu and pther groups in revolts against the Qing. According to Chinese government: “In Shuangjiang and Lancang counties, religion had come to merge with politics. Military suppression by the Qing government and defeat of the peasant uprisings led to the disintegration of local Buddhist bodies.” [Source: China.org |]

Some Lahus cremate their dead. Some bury their dead. At funerals, women carry possessions used by the deceased in his lifetime and prayers are recited and ritual offerings are made to help the soul of the dead reach the next world. Lahu distinguish between physical body and metaphysical body conceived of as comprising several distinct "souls." At death, prayers and ritual offerings are made that are designed to speed the deceased's soul to the land of the dead or Christian heaven; Those who died in violent deaths or accidents or during childbirth are given exorcisms. All work stops on the day of a burial. The grave is marked by a pile of stones.

Traditional Lahu Religion

Lahus have traditionally believed in spirits associated with natural phenomena and deceased human beings. Most spirits are regarded as overly sensitive and capricious. Great care is taken not to offend them. Spirit “bites” are believed to cause illness. Men often preside over rituals and carry out exorcisms. In Protestant and Catholic communities pastors and priest deal with spirits in addition to their other duties. The Lahu have a tradition of “warrior priests” who led rebellions and took political action because they believed they had been divinely ordered to.

The Lahu believe that the natural world is governed by the formidable and mysterious power of the spirits called “Nei (meaning inside)”, which they reckon exists in the sky, the earth, the moon, the sun, the stars, the mountains and the water, and inside human bodies. The weather, the harvest of grain and people’s health is all related to “Nei”. Their notions of fortune telling and sacrificial ceremonies are tied up with Nei. The Lahu have traditionally worshiped many gods, including deities of the earth and revenge. Their main god was Exia (Esha) is believed to have created the Universe and mankind, and has the power to decide the good or bad fortune of people. Exia exist in a forbidden place in the depth of the mountain forests, unapproachable by non-Lahu peoples. In some accounts Esha is a male god, in others, a female goddess, though anthropologist Du Shanshan has suggested that Esha is a couple of deities, one male and one female, who together created the world and all that exist. Lahu also worship gods of earth, storms, and other natural phenomena and make offerings to them. [Source: Ethnic China; Chinatravel.com]

Anthony R. Walker, wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ Even potent guardians of people, crops, and livestock (such as ancestral and locality spirits) are seen as easily offended and quick to punish. Some spirits (e.g., those of persons who have died unnaturally and those of demoniac possession) are perceived as invariably malicious. Malicious spirits are said to "bite" those who offend them, bringing sickness (often of a specific kind) to their victims. Besides such spirits, most Lahu seem to recognize, and frequently give considerable ritual importance to, a supreme and creating divinity called "G'ui-sha" (etymology obscure; Chinese scholars translate the word as "Sky Ghost"). Among Lahu Nyi, G'ui-sha is both personal deity, appropriately addressed as "Father G'ui-sha," and diffused divinity incorporating, among other supernatural beings, a female counterpart, "Mother Ai-ma." Not surprisingly, the Christian Lahu interpret G'ui-sha as the personal deity of their Judeo-Christian tradition. [Source:Anthony R. Walker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Maw-pa perform propitiatory and exorcistic rites and sometimes possess shamanistic characteristics. Some Lahu communities make a sharp distinction between such spirit specialists and priests (paw-hku), whose primary function is to mediate between the people and their high divinity, G'ui-sha. There is a long tradition of Messianic "warrior-priests" among the Lahu peoples. Beginning as revivalist leaders, such men characteristically extend their interests into the political realm, often claiming supernatural powers and divine affiliations. |~|

Bakanai Township in Lancang County has retained Lahu people's traditional facilities for making offerings -- erect poles carved with geometric designs. Traditionally, the dead were cremated. During the burial, mourners were led to the common cremation ground by women, who carried on their backs articles used by the deceased people during their life time. In some places, the dead person was buried, and the tomb piled with stones. The whole village stopped working in mourning on the burial day. |

Lahu Creation Myth

The Lahu creation myth provides a mythic explanation of the world the Lahu inhabits. It does so by describing 1) the process of creation, 2) the creation of heaven and earth, sun and moon, and human beings, and 3) early interactions between human beings and plants and animals. The details and stories about the interactions between human beings and plants and animals allowed the Lahu listeners and readers to understand these animals and plants and how they relate to themselves. The themes and constructs found in the Lahu creation myth has many parallels with the creation myths of other ethnic groups geographically or linguistically related with them. The Lahu creation myth, however, can be distinguished by the dual character of its main deities— 1) the androgynous creator Guisha; 2) the three ancestor couples A) Ca Law and Na, B) Ca Ti and Na Ti, and C) Ca Leh and Na Leh— and the special role played by the tiger among other animals. [Source: Mvuh Hpa Mi Hpa, “Creating Heaven, Creating Earth, An Epic of the Lahu People in Yunnan,” edited and introduced by Anthony Walker from a Chinese text collated by Liu Huihao. Silkworm Books, 1995; Ethnic China *]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “As is usual in this kind of mythic narratives, “Creating Heaven Creating Earth of the Lahu” follows a pattern of growing complexity. From this undifferentiated world where only Guisha existed, we are informed of the creation of Heaven and Earth—with the assistance of Ca Law and Na Law (the male and female dragon, or the male and female beings born on dragon day)—and of the sun and moon.

The second part, appropriately titled"The Creation of All Things" in English, constitutes most of the myth. It narrates the creation of water, trees and animals. People emerge from a gourd. Much of this part of the story is taken up by the history of different plants and animals and their use by the Lahu people. At last the first couple Ca Ti and Na Ti escapes from the gourd with the help of the rat. The first people marry and have sex in secret because they feel shame over it. Their children are nursed by different animals, whose eat their descendants refuse to eat. The lives of the children Ca Leh and Na Leh are described in detail. The myth on origin of fire—with a human being changing his wings to the fire seed—is very similar that of the Dulong ethnic group.

The third part, about the origin of cultural life of the Lahu narrates: 1) the origin of the different ethnic groups, according to the way they cook the meat of a tiger they hunted together and the way they choose their territory; 2) the origin of gender equality; 3) the story of swidden (slash-and-burn) agriculture; 4) the history of the medicinal plants, curiously originated from the medicine of the snake; and 5) the origin of cotton planting, writing and the new year festival.

Dogs and Snakes in the Lahu Spiritual and Daily Life

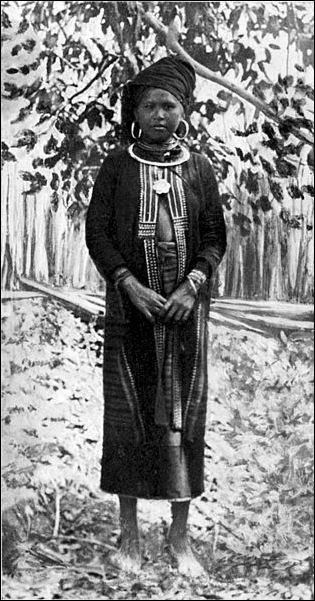

Lahu in the 1900s

The Lahu never eat dog. They have several myths that focus on the contributions of dogs to human life. In one of them, the ancestor of the Lahu was fed with the milk of a female dog (not unlike the she-wolf story of the founders of ancient Rome). In another myth, similar to stories told by other minorities, dogs delivered the five important grains that people eat to the human beings. If somebody eat dog, they must wait three days and change clothes before entering into a Lahu village. On New Year, before they eat their first meal, the Lahu first feed their dogs. The importance given to dogs is perhaps related to how important dogs are for hunting. [Source: Ethnic China *]

For the Lahu every 12th day is serpent day. The Lahu follow the Chinese calendar of 12 animals, using them to naming days and hours as well as years in a cycle. Serpent day is the equivalent of Sunday or the sabbath. On this day the Lahu don’t work, nor do they leave their house or village. This is to commemorate Zhanuzhapie death. Zhanuzhapie was a hero in the Lahu mythology, who trusting in his strength, disobeyed the orders of Esha (the main Lahu god). Zhanuzhabie was strongest man. men. One day Esha ask him why he doesn't offer part of his crops as a sacrifice. Zhanuzhabie answered that he alone worked his fields, and that he didn't need the help of the gods. This answer enraged Esha who sent to Zhanuzhapie one disaster after other, until he was killed. Lahu people don't work on Zhanuzhapie’s death day out of fear of irritating Esha and to avoid a disaster.

The importance given snakes is also manifested in two Lahu beliefs: 1) If a snake enters a home, Lahu believe it is a soul that has returned; 2) If they find a snake blocking the road, they come back home immediately. Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “ The snake represents a force that can not be understood, a beast that come from the realm of the hidden world. Its presence at home is tolerated as a strange circumstance, and is considered a spiritual phenomena. Its presence blocking the way is an unavoidable sign that the spirits consider the journey must not be continued.”

Some say that Lahu name means "those who eat roast tiger". On Tiger Day the Lahu don't sow seeds and don't plough. Chickens also have an important symbolic meaning to the Lahu. They usually receive their guests with a chicken, but it can not be a white chicken, because that means that the host doesn't want to have relations with the guest. Ox and Sheep days are not considered auspicious. Horse, Sneak, Tiger, Rabbit, Pig and Roaster days are considered suitable to start the New Year.

Lahu Festivals

There are a number of rituals involving soul sending and the exorcism of malevolent spirits. Lahu mark the major rites of passage and principal phases of the agricultural cycle with rituals ceremonies. Upright poles carved with geometric designs , shrines and bamboo poles with streamers that honor village guardian spirit play a part in the ceremonies. Some Lahu groups have village temples, which evolved from the "Buddha houses" or "Buddha halls" introduced with Mahayana Buddhism in the eighteenth century. Other important ceremonial centers includes are churches in Christian villages and ritual dancing circles. [Source:Anthony R. Walker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Lahu festivals include the Torch Festival, Tasting the New Grain Festival, Spring Festival (Lunar New Year), Xinmi (New Rice) Festival, Ancestry-Worship Festival, Kala Festival, Bridge Building Festival, Gourd Festival and, among Christians. Describing the role of music in a Lahu festival, one Lahu man told the Rough Guide to World Music, on the first day, the musicians "take a the percussion instruments and go to a bamboo pole erected in the forest. As the music plays and gets faster, so people in turn run around the pole. On the last night....we have theatrical performances, stage plays, where we play all our instruments.”

During the Torch Festival, pine wood is made into torches and ignited. Young people dress in their festival costumes and sing and dance by the campfire. Participants light torches in front of their houses and set large fires in their village squares. The festival honors a woman who leaped into a fire rather make love with a king. Before the village torch is lit people gather around it and drink rice wine. The Kuo Festival is a big event. It features circle dancing. The climax of one Lahu festival is when seven men tie pieces of a sacred wood tiger and people one by one try to break them apart. The fact they cannot break the wood symbolizes the power of nature and the unity of the Lahu people.

The Changxin Festival is the Lahu harvest festival. Changxin means tasting the new. During the festival, villagers kill pigs and make wine, and every person takes a rest for two days. Before the festival, people harvest a part of their total harvest and make sacrificial ceremonies to their ancestors. After that, they begin the real harvest. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

Lahu Spring Festival

Spring Festival, also known as New Year, is pronounced as "Kuonihani" in the Lahu language. It lasts from the first day to the ninth day of the first lunar month, more or less the same as The Spring Festival of the Han Chinese (Chinese New Year). The Lahu, however, break down the festival into Bigger and Lesser festivals. The Bigger Festival lasts from the first to the fifth of the first lunar month. The Lesser Festival, known as "Lahu Men's Festival", lasts three days, from the seventh day to the ninth of the first lunar month. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Spring Festival is thus divided because, according to Lahu's legends, in ancient times men went out hunting during the Spring Festival. When they came home, New Year's Day had already passed. Therefore, their wives wanted to make up it them and have a delayed celebration after they returned. Demonstrating the place of men in Lahu society and the value given gender equality the second festival for men is either called the Lesser Festival or "Men's New Year's Day." And the former New Year's Day is called "the Bigger Festival" or "Women's New Year's Day." About this custom, there is another story: In ancient times, the Lahu were often harassed by other groups. In order to show their strength and defend their homeland, Lahu men often participated in military expeditions in faraway lands. When they came back in triumph, the New Year Festival was over. However, to celebrate their triumph and reunion, they had another New Year's Day, which was celebrated with dancing and singing. This practice has been handed down from generation to generation until now. ~

"Competing for New Water" and "Lusheng Dance" are two popular and special festival activities observed at the Lahu's celebration of Spring Festival. "Competing for New Water" takes place on the first day of the lunar year. Each family picks a member to run to a certain spring to fetch the "new water." It is regarded as a very important business of a new year, because for the Lahus, the "new water" is sacred, and a symbol of good luck and happiness. The one who first gets the "new water" brings a rich harvest of grains and fruits and good luck for his or her family. Therefore, in the early morning of New Year’s Day, when a cock heralds the break of day, every family's representative member rushes to the spring to get the "new water." After the water is brought back home it is first offered to ancestors as an act of worship, and then given to the elderly for washing their faces. ~

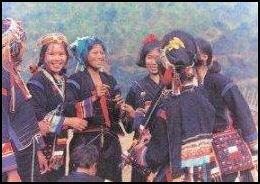

During the Spring Festival, every village holds a big lusheng dance, in which everyone, old and young, man and or woman, take part, in their best festival clothes. They gather in a clearing with several or even dozens of men in the center playing the lusheng (a reed pipe) or leading the dance. Women, then, join their hands and form a circle around, dancing and singing to the rhythm of the music. As a group dance, the Lahus' Lusheng Dance is very colorful. Some dances represents their working chores; others imitates the movements and gestures of animals. Because of its delicacy and passion, it is the most favored dance of the Lahu people. ~

Image Sources: Wiki Commons Nolls China website

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China “, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China 4) Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022