SHAN

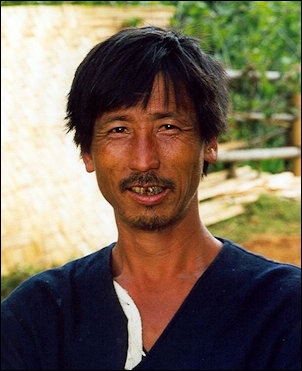

Shan Man

The Shan are the largest minority of Myanmar (Burma). They are a relatively prosperous minority related to the Dai in China. Their language is similar to Thai and Lao. They have traditionally been rice cultivators and lived in tropical and semitropical monsoon forests along river valleys and in pockets of level land in the hill country of northeast Burma and to a lesser extent in northwest Thailand and southern China. Some other groups regard the Shan as “a standoffish people.”

The Shan are related to the people in Thailand, Laos and Yunnan Province in China. They tend to have taller and fairer than the Burmese. Shans reside mostly in eastern Myanmar in the Shan State (See Below), but also inhabit parts of Mandalay Region, Kachin State, and Kayin State, and in adjacent regions of China (where they full into the Dai people category), Laos, Assam (Ahom people) and Thailand. The Shan have traditionally settled in valleys and river basins rather than in the mountains. [Source: Nicola Tannenbaum“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

'Shan' is a generic Burmese term used by Westerners for all Tai-speaking peoples within Myanmar (Burma). Most Shans are Theravada Buddhists. Until recently they lived within a distinctive structure of feudal states ruled by hereditary princes. The Shan are also known as the Burmese Shan, Chinese Shan, Dai, Hkamti Shan, Ngiaw, Ngio, Pai-I, Tai Khe, Tai Khun, Tai Long, Tai Lu, Tai Mao, Tai Nu and Thai Yai. The Pa-O, Paluang, Danu, Taungyo are all members of the Shan tribe. The Shan refer to themselves as “Tai,” often with a second name attached to identify their subgroup, and call their homeland Ta-Land. The Shan and Thai often view themselves as brothers. The Thai call the Shan the Thai Yai.

The Shan People and Palaung People in Myanmar and the Dai, De’ang, Bouyei and Dong in China are related. See SHAN LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com; PALAUNG factsanddetails.com ; DAI MINORITY factsanddetails.com; BOUYEI MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com DONG MINORITY AND THEIR HISTORY AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “History of the Shan State: From Its Origins to 1962" by Sai Aung Tun; Amazon.com; “Imagining the Course of Life: Self-Transformation in a Shan Buddhist Community” by Nancy Eberhardt Amazon.com; “Turbulent Times and Enduring Peoples: Mountain Minorities in the South-East Asian Massif” by Jean Michaud and Jan Ovesen Amazon.com; “The Moon Princess: Memories of the Shan States” by Sao Sanda Amazon.com; “The White Umbrella: A Woman’s Struggle for Freedom in Burma” by Patricia W. Elliott Amazon.com; “The Ethno-Narcotic Politics of the Shan People: Fighting with Drugs, Fighting for the Nation on the Thai–Burmese Border” by Thitiwut Boonyawongwiwat Amazon.com; “The Golden Triangle: Inside Southeast Asia's Drug Trade” by Ko-lin Chin (2009) Amazon.com; “From Opium To Methamphetamines: The Nine Lives Of The Drug Industry In Southeast Asia” by Wolfgang Sachsenroder (2022) Amazon.com ; “The Hunt for Khun Sa: Drug Lord of the Golden Triangle” by Ron Felber Amazon.com;“The Reluctant Warlord: On the Trail of America's Most Wanted Man” by Patrick King Amazon.com; “Khun Sa Warlord and Heroin Kingpin” by Ron Chepesiuk Amazon.com

Shan State

Shan State lies on the Eastern Plateau of Myanmar, east of the Irrawaddy and Sittaung valleys, south of the Bhamo district and north of Kayah State. It is the home to about half the population of Myanmar. Ethnic groups that live here include the Shan, Burmese, Chinese, Wa, Kachin, Paluang, Lahu, Akha, Pa-O, Kachin, Palaung, Danu, Wa, Lahu, Kaw, Maingtha, Paduang, Taungyo, Yin, Gon, Kayah, Lishau, and Intha. For a long time much of Shan State was off limits to tourists because of opium production and fighting connected with ethnic insurgencies in the area. Open areas include Kalaw, Inle Lake, the Shan plateau, the Shan Hill, Inle Lake, Taunggyi, Pindaya and the roads that connect these places.

Shan State is divided into Northern Shan State, Southern Shan State and Eastern Shan State. Districts of Shan State include Taunggyi, Loilem, Lashio, Muse, Kyaukme, Kunlong, Laukkai, Kengtung Mongsan, Monhpyak and Tachileik. Shan State is formed with 54 townships and 193 wards and village-tracts. The capital of Shan State is Taunggyi.

The region is dominated by Shan plateau, which is between 915 meters (3,000 feet) and 1,220 meters (4,000 feet) above sea level and has a climate that is comfortable year round and less hot than the lowlands. The mountain ranges threading through the area are generally between 1525 meters (5,000 feet) and 2,37 meters (7,000 feet high). The valleys are filled with wet and dryland rice fields, irrigation canals, ponds, trees, water buffalo, lotus flowers, small pagodas, and footpaths.

See Separate Articles EASTERN AND NORTHERN SHAN STATES: BURMA ROAD, MAYMYO, DRUGS, MEKONG AND CHINESE GAMBLERS factsanddetails.com KALAW, TAUNGGYI AND SOUTHWESTERN SHAN STATE AND KAYAH STATE factsanddetails.com

Shan Population and Groups

Shan State in Myanmar

It is estimated that there are between 5 million and 6 million Shan, with about 90 percent of them in Myanmar. No reliable census has been taken in Burma since 1935.The CIA Factbook estimates there are five million spread throughout Myanmar, which is about 10 percent of Myanmar’s population. There is small number of Shan in Thailand.

Population estimates are questionable at best. Reports from Myanmar typically underreport minority populations, in part of political reasons. A 1931 British census reported 1.3 million Shan in Burma. The lack of good information on Shan numbers in Myanmar is due also to hostilities there between the Shan and the Myanmar government. Thai census figures do not include a separate Shan figure since most are Thai citizens. The Dai are the 19th largest ethnic group and the 18th largest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered 1,329,985 and made up 0.09 percent of the total population of China in 2020 according to the 2020 Chinese census.

There are 33 Shan ethnic groups (or subgroups) recognized by the Myanmar government (in parentheses, where they stand among Myanmar’s 135 ethnic groups): (103) Shan, (104) Yun (Lao), (105) Kwi, (106) Pyin, (107) Yao, (108) Danaw, (109) Pale, (110) Eng, (111) Son, (112) Khamu, (113) Kaw (Akha-E-Kaw), (114) Kokant, (115) Khamti Shan, (116) Hkun, (117) Taungyo, (118) Danu, (119) Palaung, (120) Man Zi, (121) Yin Kya, (122) Yin Net, (123) Shan Gale, (124) Shan Gyi, (125) Lahu, (126) Intha, (127) Eik-swair, (128) Pa-O, (129) Tai-Loi, (130) Tai-Lem, (131) Tai-Lon, (132) Tai-Lay, (133) Maingtha, (134) Maw Shan, (135) Wa

Mostly Danu, Taungyoe, Intha (Ansa) and Bamar are living in the western part of the Shan State.A lot of Palaung (Taahn) are found in the northern part of Shan State, especially at Namsam Town, and also in Pindaya. Yatsauk and Maingkaing Townships. Many Paos have settled in the southern part of Shan State, whereas Kachin and Lisu (Lishaw) live in the north. Kokant Tayok occupy the Kokant region. Wa (Lweila) live in Hopan Township which is situated to the the east of Thanlwin river. E-Kaw (Akha) and Lahu reside in Kyaingtong region.

Early Shan History

The origin of the Dai, Shan and Dai-related people is matter of some debate. They have been in southwest China and Southeast Asia for some time. The Dai established powerful local kingdoms such as Mong Mao and Kocambi in Dehong the 10th and 11th centuries, the Oinaga (or Xienrun) in Xishuangbanna in the 12th century and the Lanna (or Babai Xifu) in the northern Thailand in 13th to 18th century.

The Shan migrated from southern China to Burma around A.D. 1000. Over time they established a number of small states in the mountainous regions of northern Burma. They paid tribute to China, Burma and Chiang Mai and became powerful landlords, dominating other ethnic groups and in some cases making them into their serfs. The Shan-controlled areas were on the fringes of the Chinese, Burmese empires and separated from the main population centers by rugged mountains and rain forests.

The Shan were once united but their empire split into small kingdoms in the 16th century ruled by hereditary princes called “saophas”. They usually fought among themselves and only offered minimal tribute to the Burmese kings.

See DAI MINORITY AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com

Later Shan History

At the time the British took over Burma, there were 18 Shan major states ruled by princes and 25 lesser states ruled by officials. Most Shan states paid tribute to Burma. The most easterly states, however, had stronger relations with Chiang Mai and Central Thailand. Under British rule, the states were administered indirectly by the Shan princes. When the borders for Thailand and Burma were drawn up the line was drawn through Shan territory. When Burma became independent in 1949, the Shan principalities were united into the Shan State.

Since the 1950s, the Shan have engaged in a military struggle against the Burmese-Myanmar government. Their goals have raged from full independence to more autonomy. The Shan in Thailand are not involved in this struggle. Some of the Shan militias and Shan groups have been involved in the opium trade.

Shan sultan in 1906

The Shan State Army signed a peace agreement with the Myanmar government. The Shan State Army, the United Wa State Army, and the Kachin Independence Union all signed peace agreements with the government. The agreement promised the ethnic groups more autonomy and allowed some to grow opium unmolested. By 1996, the government had signed peace treaties with 11 of the countries 12 ethnic groups. Even the country's largest drug kingpin and warlord, Khun Sa, had made a deal with the government by then. The only remaining major guerilla group was the Karen National Union. The treaties were far from final resolutions to the insurgency problems. After Khun Sa made a deal with the government some of his fighters continued fighting.

See Separate Article SHAN STATE ARMY, SHAN POLITICAL GROUPS AND THE SHAN INSURGENCY factsanddetails.com

The White Umbrella: A Shan Woman’s Struggle for Freedom in Burma

“The White Umbrella: A Woman’s Struggle for Freedom in Burma” by Patricia W. Elliott is a true tale of modern Burma told through the life story of Sao Hearn Hkam. Sao (Princess) Hearn Hkam was the wife of Sao Shwe Thaike of Yawnghwea, who became the first president of Burma. He died under mysteriosu circumstances after the coup by Gen. New Win in 1962. After her husbands death she joined the resistance and was elected president of the Shan State War Council, a position she held until 1969 when she went into exile in Canada. She died in Canada in 2003 at the age of 86.

According to promotional material for the book: “Born into royalty, sold in marriage like a slave, Sao Hearn Hkam fought against tradition, foreign invaders and the brute power of a crazed general to gain freedom for her people. She has been called Princess, Mahadevi, First Lady, Member of Parliament, rebel leader, refuge. From the quiet Shan hills of her childhood to the Presidential Palace in Rangoon; to the halls of power in Asia and Europe; and finally to the violent, drug-laden netherworld of the Golden Triangle, her journey is an inspiration and a revelation — about Burma, about Southeast Asia, and about what happens when the games of super-powers are played out in real life.

Book: “The White Umbrella: A Woman’s Struggle for Freedom in Burma” by Patricia W. Elliott (2006).

Shan Language

Shan word for Tai

Many if not most Shan speak a Shan language and are bilingual in Burmese. The Shan speak Thai, which is very similar to Lao and the Thai spoken by Thais. The Shan use four written languages: Tai Long, Tai Mao, Tai Khun and Tai Lu. Tai Long and Tai Mao resemble Burmese. Tai Khun and Tai Lu are similar to Northern Thai. The Shan alphabet is an adaptation of the Mon–Burmese script via the Burmese alphabet. Few Shan are literate in their own language anymore. In the old days, the scripts were used primarily for religious and court purposes. Most of those who learned to read and write did so when they were monks. Some women also learned to read and write. Now most Shan kids attend school of some sort and mostly learn to read Burmese. [Source: Nicola Tannenbaum, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Thai, the Shan language, is part of the family of Tai languages. It is spoken in Shan State, some parts of Kachin State, some parts of Sagaing Division in Burma, parts of Yunnan, and in parts of northwestern Thailand, including Mae Hong Son Province and Chiang Mai Province.[ The two major dialects differ in number of tones: Hsenwi Shan has six tones, while Mongnai Shan has five.[Source: Wikipedia]

The Shan language is declining but efforts are being made to keep it alive Reporting from Taunggyi in Shan State, Kelly Macnamara of AFP wrote: “For half a century a single precious copy of a textbook kept the language of Myanmar's Shan people alive for students, forced to learn in the shadows under a repressive junta. Now with a reformist government reaching out to armed rebel groups after decades of civil war, calls are growing to reinstate ethnic language teaching in minority area state schools as part of reconciliation efforts. "Shan is the lifeblood of the Shan people. If the language disappears, the whole race could disappear too," said Sai Kham Sint, chairman of the Shan Literature and Cultural Association (SLCA) in the state capital Taunggyi. [Source: Kelly Macnamara, AFP, October 21, 2012]

Photocopies of the cherished Shan book have been used in private lessons for years in the eastern Myanmar state, after the original was banished from the curriculum by a regime intent on stamping out cultural diversity. Shan activists this year finally felt able to print a new edition as the country formerly known as Burma emerges from decades of military rule. The SLCA runs its own summer schools, giving students basic training in written and spoken Shan and familiarising them with such classics of local literature as "Khun San Law and Nan Oo Pyin" — a tale of lovers who turn into stars after their deaths.But Sai Kham Sint said allowing teachers to hold Shan classes in state schools "without fear" would help sustain the language. The Shan language is akin to Thai spoken just across the border. The original book's beautiful illustrations of snakes, elephants and monks carrying alms bowls evoke the pastoral lifestyle of the lush, mountainous region when it was first printed and used in schools in 1961, a year before the start of almost half a century of military rule. Photographs have replaced drawings in the new edition, but no one has yet taken up the challenge of updating the text. "

Shan Religion

Shan monk

Most Shan are Buddhists or Christians. Some Muslims and Hindus live in Shan State. The Shan are mostly Theravada Buddhists which bonds them more closely to the lowland Burmese and Thais than it does to many of the highland minorities. Families have traditionally sent their sons to become monks under the belief that doing so would earn their family’s merit. Most villages have temples. [Source: Nicola Tannenbaum,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Shan were animist before they embraced Buddhism and beliefs in natural spirits have remained alive. Religious practitioners include Buddhist monks, novices, and nuns; temple lay readers; traditional curers; and caretakers of the village spirit altar. They draw from both Buddhism and animism when they perform rites and conduct healing ceremonies. The latter are often basically shamanist rituals with Buddhist verses often blown over the patient or recited over water the patient drinks. A traditional healer's ability to heal is connected to his keeping of Buddhist precepts.

The idea of “power protection” is central to the Shan belief system. The Shan believe that one gains power protection from making friends among capricious spirits and keeping them happy and that this power protects people from the consequences of their action and is unequally distributed. This is a pretty unorthodox view for people who consider themselves Buddhists. So too is the belief that monks possess great power and deities associated with Buddhism are regarded as being more reliable than others.

There are a number of different kinds of spirits — those linked with natural phenomena, those linked with the heavens, and those linked with ancestors, household gods, and ghosts — are they are hierarchically ranked. Human beings are ranked in the middle. Beings more powerful than humans include Buddhas, land spirits of the village, and spirits associated with fields, households, and the forest. Beings ranked below humans are considered very dangerous. Among these are spirits that arose from violent deaths or from women dying in childbirth and disease spirits.Buddhism is also incorporated into this schema.

Shan Funeral

The Shan embrace Buddhist beliefs about the afterlife and reincarnation but also believe that people became spirits after they die and these spirits are everywhere and some are good and some are malevolent.

Funerals occur three to seven days after death. Most people are buried. Sometimes people who die “bad deaths” are cremated. Buddhist monks perform rites. Commoners have traditionally been buried while monks and aristocrats were cremated. Commoners that died natural deaths are buried in cemeteries in the woods near a village. People who died in accidents or as a result of violence are buried far away from everyone else because it is believed that these dead people become evil spirits.

When a person is near death, two pieces of yellow cloth and a small bamboo tablets from a temple are placed on him to assist in the admission to paradise. All work comes to a stop for it is believed that spirits dislike the sound of work. Monks perform rites at the house of the deceased. When the coffin is carried from the house the spouse of the deceased cuts a candle in half, symbolizing her separation from the dead. When the funeral is over people purify themselves by washing their hair with water and expose their skin to smoke of a burned nut.

Shan Festivals

The Shan celebrate a number of Buddhist holiday and conduct a number of Buddhist ceremonies and rituals, which often involve making offerings of food and flowers to Buddha at both temples and family altars in people’s homes. There are temple festivals celebrating events in the Buddha's life, such as the anniversaries of his birth, his enlightenment, his first sermon, and his death. [Source: Nicola Tannenbaum, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Shan Festival

The Shan follow the Buddhist lunar calendar. There are four holy days each month, falling on full, new and half moons. There are festivals celebrating events in Buddha’s life and important dates relating to agriculture and the beginning and end of the rainy season. Households conduct a number of ceremonies. Most villages invite monks in for an annual cleansing ceremony.

Many festivals feature sand pagoda building and rockets before or after the rainy season and to honor the end of the retreat of forest monks during the three months of rain.. One of the biggest events on the Shan calendar is the Water Splashing New Year's festival in mid-April in which demons are washed out with old year and rockets are launched and swimming races are held to usher in the new year.

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ Wealthy villages and temples celebrate more of these events than do poorer ones. However, all villages at least hold a festival after the end of the rains' retreat. Once a year villages as a whole invite monks to chant to remove misfortune and to renew the village and its constituent households' barriers against misfortune. The village cadastral spirit is also feasted at least once a year. Households may sponsor a range of ceremonies including Buddhist ordinations, funerals, merit making for the dead, marriages, first bathing ceremonies for infants, and invitations for monks to chant in the house.

Small Ethnic Groups That Live in Shan Areas

Khamu ethnic tribes are mainly found in northern Laos, Myanmar, southwestern China and Thailand. In China, they live primarily in Guizhou Province. In Myanmar, the Khamu are categorized under the Shan ethnic group since most of them live in Shan areas of the country. Some countries do not recognize the Khamu as a separate ethnic group and are placed under the broad category of undistinguished nationalities. But they are recognized as the Khamu in Myanmar. Their native language is called Khamu. They do not use money in their villages; rather they rely on a barter system. [Source: Myanmar Travel Information]

Kokant are an ethnic group found in Panlon and Laukkai in northern Shan State. They have traditionally raised opium poppies. In 1997, the Myanmar government began encouraging them to grow sugar cane, buckwheat and durians instead of opium. The durians planted in the area are now exported to China. Kokant villagers earn surplus income mainly from shoes and traditional rain coat manufacturing. The cultivation of buckwheat in sugarcane and the establishment of factories has eased the problems of unemployment and reliance on opium for income. Kokants have traditionally worshiped their ancestors. Soothsayers associated with Nat Saya tell the future by using the bones of chickens. See Opium and the Golden Triangle [Source: Myanmar Travel Information]

Shan ceremony in the early 1900s

Eng can be found 20 kilometers (13 miles) north of Kyaung Tong in a hilly region of Eastern Shan State in a village called Nant Lin Taung. The village has 20 households living in thatch roofed huts built on tamped reddish earthen stopped. The meaning of the name of the national tribe “Eng” is “Running in Shan dialect. Some Eng are Buddhists and some are animist who believe in traditional spirits. They offer their spirits and a traditional liquor called Kaungyay during their new harvest festival. Their costume are is black for both males and females. Women usually wear flowers or earings. The Eng are possibly related to the Wa tribe. They live only in the foothills of the Kyaing Tong basin. Eng women often marry at the age of 14 or 15. They wear colorful ornaments. Their villages are built along mountain ridges and they use bamboo pipes to pipe in water. The Eng hold their harvest festival at the full moon in November.

Palaung

The Palaung are an ethnic group that resides mostly in the Shan States in east central Myanmar, with the majority of them living in narrow valleys or along the slopes and ridges of 2000-meter-high mountains around Kalaw in Taungpeng State near the border with Thailand.

The Palaung are also known as the Dang, Humai, Kunloi, La-eng, Palong, Ra-ang, Rumai, De’ang, Deang, Tang and Ta-ang. It is believed that there are around 200,000 of them although no accurate census data on them exists. They are sometimes linked with the Wa although both the Wa and the Palaung deny they have any relation.

Palaung speak an Austroasiatic language in the Mon-Khmer group and have traditionally practiced animism and Buddhism . They probably preceded the Shan and Kachin in east central and northeast Burma and established themselves in the Taungpeng area, where they traded mostly with the Shan. A lot of Palaung (Taahn) are found in the northern part of Shan State, especially at Namsam Town, and also in Pindaya. Yatsauk and Maingkaing Townships. There are many in the Kalaw area in Shan State.

See PALAUNG factsanddetails.com

Pa-O

The Pao people live mostly in Shan State. There are about 60,000 of them. They are deeply rooted in Buddhism and have a close affiliation with the Burmans (Bamar). According to the Myanmar government less than 1 percent of them are Christians. They have the New Testament in their own language translated by the missionary in 1961. Ths book is used not only by Pao Christians but by Pao non-Christians to learn to read and write in their own language. [Source: Myanmar Travel Information]

Poi Song Long Festival

The typical Pa-O village of Nant Bay forms a long stretch of dwellings in Southern Shan State and lies between two mountain ranges running from south to north. There are over 100 houses built with cherry and pinewood. Some have giant bamboos. Every house is fenced. Thatch is used mostly for roofing but some use zinc sheets. As the houses stand on long legs, buffalos and cows can be bred under them. Nant Bay villagers rely on mountain streams, which continuously flow in the region.

Water from the stream is saved in small reservoirs. When the water is released the force of the water turns a the water wheel and 25 KVA hydroelectric power can be generated on self-reliant basis. Some villagers collect water at their houses and grind rice and grain using water wheels. As Nant Bay Village is situated in a wide valley where agriculture is favourable, not only the main staple rice is grown but also garlic and pigeon pea are grown well. For agriculture. rainwater is also essential. Therefore. every July. Nant Bay villagers use to wish for rains in their traditional way. In Myanmar. such kind of occasion is called Moe Kyoe Pwe. the rain welcoming ceremony.

Maingtha

The Maingtha ethnic group is also known as the Achang or the Nga Ang. They live in Myanmar and China. About 27,000 live Yunnan Province, China. They live in the northern Shan State of Myanmar. Their native language is known as Achang. It can be written with Chinese characters.

There are legends about the origins of the Maingtha people in China. The ancestors of the Maingtha are regarded as among the first inhabitants of Yunnan. They lived near the Lancang river. During the 12th century they began to emigrate to the west of the river. By the 13th century some of them settled down in the area of Longchuan around Lianghe. During the Ming and Qing dynasties they were governed by local village heads.

Music is one of the mainstays of their culture, with songs and dances providing a climax to all their celebrations. Unmarried young people usually comb their hair with two braids that gather on their head. Achang clothing varies according to village. Married women typically dress in long skirts whereas unmarried ones wear trousers. The men favor blue or black shirts with buttons running down the sides. Unmarried men wear a white headband whereas married ones wear blue headbands.

Their religion is Hinayana Buddhism, Taoism and a mixture of animism and ancestor worship. In Buddhist funerals of the Maingtha a long fabric tape of about 20 meters is tied to the coffin. During the ceremony the monk in charge of the ritual it walks in front of the coffin holding the tape. By doing this the monk helps directs the soul of the decreased to its final destiny. The deceased is buried without any metal or jewels, since it is believed that these elements contaminate the soul for future reincarnation.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: East and Southeast Asia”, edited by Paul Hockings (C.K. Hall & Company); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, National Geographic, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2022