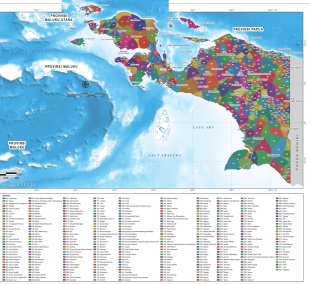

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA)

Papuan communities in the highlands of Western New Guinea have many similarities. Most eat the same foods and have traditionally lived in patrilineal clan groups led by men who continually had to demonstrate their authority. Fighting and warfare were common and typically occurred between clans of the same ethnic group. Differences between the main highland groups — the Dani, Eipo, and Damal — are most conspicuous in ritual practices and the scope of trade relations. [Source: Similarities and differences among Mountain Papuans, Stichting Papua Erfgoed]

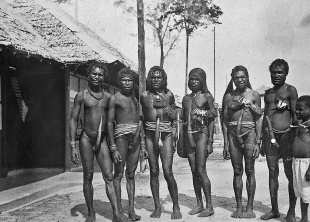

Across the Central Plateau, Mountain Papuans are farmers who cultivate largely the same crops. Sweet potatoes are the staple—both tubers and leaves are eaten—along with keladi (taro), cassava, corn, sugarcane, bananas, oil or nut pandanus (depending on altitude), and various vegetables. Pigs are also kept. Material culture shows similar patterns: men typically wear penis sheaths and women short skirts, and both use netted head-carried bags of all sizes for transport. Old, worn cowrie shells function as currency.

Among the major differences are the size of festivals, the performance of rituals, styles of warfare, and the reach of trade networks vary widely. Some groups practice “concentrated” marriage ties, favoring unions between two neighboring clans, while others do not. Leadership qualities also differ: some groups value martial courage, others organizational or economic skill, and still others ritual innovation. Economic strategies range from near-total reliance on agriculture to substantial dependence on hunting and gathering. Farming intensity also varies; elaborate water-management systems—striking to early European observers—occur mainly in the Panai region and the Baliem (Grand) Valley.

The Moskona tribe lives in a remote part of Papua that is surrounded by sheer 2,130 meter (7,000) foot peaks and can only be reached by air. Up until the late 1970s the group lived in tree houses and killed the few outsiders that trespassed on their land. Writer Arthur Zich visited them and said they had some good one liners as well. Zich asked one chief if he had heard about the Second World War. The chief said, "I never even heard of the first one." A girl piped in, "Eight years ago we didn't even know what country we were in, or what a county was." When asked how the government had made its presence known, the chief said, "They came...and told us not to kill the missionaries anymore." The Moskona live in various villages in districts like Moskona Timur, Mardey, Masyeta, and others within the Teluk Bintuni Regency of West Papua. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population (as of the early 2020s) is 34,000 and 75 percent are Christians, [Source: Arthur Zich, National Geographic, January 1989; Google AI, Joshia Project]

RELATED ARTICLES:

DANI AND PEOPLE OF THE BALIEM VALLEY: HISTORY, RELIGION, WHERE THEY LIVE factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF DANI PEOPLE OF WESTERN NEW GUINEA: SOCIETY. FOOD, SEXUALITY factsanddetails.com

BALIEM VALLEY: HISTORY, PEOPLE, TRAVEL, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN PAPUA AND THE BIRD'S HEAD (VOGELKOP) OF NEW GUINEA factsanddetails.com

NORTHWEST PAPUA AND THE BIRDHEAD OF NEW GUINEA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

FREEPORT (GRASBERG) GOLD AND COPPER MINE IN PAPUA, INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

PROBLEMS AT THE FREEPORT MINE: VIOLENCE, POLLUTION AND BRIBES TO THE MILITARY factsanddetails.com

Dani

Dani is a somewhat pejorative term used by outsiders to describe groups around the Baliem Valley, the main tourist area of Papua. Also known as the Akhuni, Konda, Ndano and Pesegem and sometimes spelled Ndani, they have traditionally lived in circular thatch-roof huts and subsist primarily on sweet potatoes. The different Dani groups have different languages customs and styles of clothing. Some are former Stone-Age cannibals. [Source: Karl Heider, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Oceania”edited by Terence Hays, (G.K. Hall & Company, 1996) ~]

Known as the “gentle warriors”, the Dani have only recently emerged from the Stone Age. Yet with their simple tools of stone and bone, they managed to sculpt green fields that hug the hills of the Baliem Valley, where they grow root crops, and raise pigs. They have also built outposts and lookout towers to defend their valley from hostile tribes. Because the land is fertile soil and crops are raised with agricultural skills, the Dani together with the sub-tribes of the Yali and the Lani have made the Baliem Valley the most populous area in Papua, living scattered in small communities near their gardens among the steep mountain slopes. Today, they mostly cultivate bananas, taro, yams, ginger, tobacco and cucumbers. Pigs are greatly valued. The men's and women's huts (locally called the honai) have thick thatched roofs, which keep the huts cool during the day and warm during the cold nights.

See Separate Articles: DANI AND PEOPLE OF THE BALIEM VALLEY: HISTORY, RELIGION, WHERE THEY LIVE factsanddetails.com LIFE OF DANI PEOPLE OF WESTERN NEW GUINEA: SOCIETY. FOOD, SEXUALITY factsanddetails.com

Eipo

The Eipo live in a 150 square kilometer (58 square mile) area in the southernmost section of the Eipomek Valley on Eipo River in the West New Guinea highlands at elevations between 1,600 meters and 2,100 meters (5,250 to 6,890 feet). The area is surrounded by mountains with 4,600-meter-high 15,090-foot-high peaks that get 5.9 meters (19 feet) of rain a year. Also known as the Eiopdumanang, Goliath, Kimyal and Mek, they live in villages centered around a men’s house, with women’s houses around the periphery where women stay when they are pregnant or menstruating, The Eipo are small in size, weighing on average around 40 kilograms. [Source: Wulf Schiefenhövel, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Eipomek Valley is located in the in the Daerah Jayawijaya region in the central mountain highlands in the Star Mountains Regency (Kabupaten Pegunungan Bintang) within the province of Highland Papua. The Eipo people usually refer to themselves as "Eipodumanang," meaning "those who live on the banks of the Eipo River." However, the term "Eipo" is sometimes used to refer to the inhabitants of adjacent valleys as well. Linguists and anthropologists have introduced the term "Mek," meaning "water" or "river," to designate the fairly uniform languages and cultural traditions in this area. The terrain where the Eipo live is steeply incised. Grasslands surrounds the villages in a wide circle. Rainforest exists between the garden areas. Rains falls mostly in the afternoons and evenings. Temperatures range from about 11-13°C to 21-25°C. There is little seasonal change, but the Eipo use the flowering time of a particular tree (Eodia sp.) as a marker for certain feasts and activities. In 1976, two severe earthquakes destroyed large areas of gardens and some villages. Similar catastrophes likely occurred in the past. ~

The Eipo is a small group. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 5,100. Estimates in the past counted around 1,000 members in the 1990s and 800 in the 1980s. The Eipo are known for a rapid transition from a traditional society to modernity. They have become proficient in modern technologies, education, and commerce, despite having lived in relative isolation. Their traditional culture is rich with spiritual beliefs connected to ancestors and their environment.

Eipo language is called Lik. It belongs to the Eastern branch of the Mek language family within the Trans–New Guinea phylum and is distinct from neighboring Ok, Yali, and Dani languages. Eipo includes three dialects, and local people traditionally understand — and sometimes speak — one or two neighboring dialects or languages, partly because exogamous (outside group) marriage brings in women from other valleys. Children often learn their mother’s dialect rather than the dominant local speech. Eipo shares much of its vocabulary with Una and Tanime, forming a broader dialect area. Bahasa Indonesia, unknown in the region before the 1970s, is slowly spreading as a lingua franca.

History: No archaeological or ethnohistorical studies exist for the Mek region, but it is likely that parts of it have been inhabited for thousands of years. Linguistic and cultural evidence — including the spread of tobacco and shared religious concepts like the ancestral creator figure — suggests the Mek and their Ok neighbors played a central role in transmitting cultural ideas from east to west. Before the sweet potato arrived, taro held major ceremonial importance, indicating its prominence in earlier subsistence systems. The first recorded outside contact occurred in the early 20th century, when Dutch surveyors near Mount Goliath documented a few Mek words; later contacts included a 1959 French expedition and Pierre Gaisseau’s 1969 parachute entry into the southern Eipo Valley. Extensive documentation began with German researchers who lived among the Eipo between 1974 and 1980. Since then, the Eipo have undergone rapid social change. Within a single generation they have adopted literacy, modern tools, and new economic systems. Many pursue higher education in Papua and in Indonesian cities such as Jakarta and Bandung, and Eipo professionals now serve as teachers, nurses, administrators, and elected representatives.

Worth a Look: “The Dramatic Pace of Acculturation and the Ability of So Many Eipo to Jump From Stone Age to Computer Age in One Generation … Without Having Read Aristotle” by Wulf Schiefenhövel mprl-series

Eipo Religion and Culture

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 65 percent of Eipo are Christian, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent. Christianity to some extent has displaced traditional religion, which emphasized a belief in spirits of the forest and holy relics that contained mythical powers and seers who could communicate with the dead. Eipo culture has a strong connection to ancestor worship and rituals related to survival. Syncretic ideas and ceremonies are quite common and cargo-cult concepts exist. [Source: Wulf Schiefenhövel, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Eipo have traditionally believed the world is filled with many powerful, often fearsome beings—ancestral spirits, animal-like forest and river entities, and culture-shaping figures who have influenced human life since mythic times. The most important of these is Yaleenye (“the one who comes from the east”). Sacred artifacts are carefully preserved. Sacred relics linked to mythic powers were traditionally kept in men’s ritual houses, where ceremonies were performed to protect the health of people, livestock, and crops.

Death has traditionally been marked with a great amounts of wailing and lamenting. The corpse was traditionally placed in a tree and protected from rain by a covering of leaves and bark. After it mummified with was placed under the roof of a garden house and later, with a ceremony, placed in a rock shelter. These days with the influence of Christianity many times the dead are buried. The spirits of the dead are regarded as malevolent and the aim of post-death rituals is to dispel them as quickly as possible to a mythical ancestral village where they can not harm the living. ~

In the past seerss serves as the primary intermediaries with the supernatural, capable of both healing and sorcery. Male cult leaders—often also big-men—formerly oversaw major rituals, while a small group of specialists acted as healers. Traditional healing relies on few plant medicines; treatments commonly use stinging nettle leaves, sacred pig fat, and ritual chants to draw on supernatural aid. Healers typically receive no payment, and in recent times some mission stations have introduced modern medical practices ~

Initiations for boys between the ages of 4 to 15 were traditionally are held every 10 years or so and involved the presentation of a penis gourd, cane waistband and special ornaments that are hung from the head down on the back. The event was celebrated with a big, costly pig feast with dancing. There were also ceremonies for killing an enemy. ~

The Eipo make few carved or painted objects. Some Mek groups have sacred boards and large shields that were not used in war. Drums are only known in some areas, but Jew's harps are found everywhere. The texts of profane songs and sacred chants use powerful metaphors and are highly sophisticated examples of artistic expression. ~

Eipo Society, Family and Sexuality

Eipo society revolves around extended families, lineages and clansmen house communities. Villages are led by big men chosen on the basis of their oratory skill and physical size. On the surface they seemed friendly and controlled but in the past at least they had an aggressive streak that was easily triggered and could take the form of a verbal quarrel or a physical attack with sticks, stone axes or arrows. Conflicts were often between neighboring groups and occasionally cannibalism was practiced. On average in the 1980s three to four people out of 1,000 died violently ever year. [Source: Wulf Schiefenhövel, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

An Eipo household typically includes a woman, her husband, their young children, and sometimes unmarried or elderly relatives, along with a dog or small pigs. Parents may work together, and gardens are common sites for sexual relations. Children are raised with close physical contact and responsive care, especially by mothers. They interact with many people and gradually face increasing discipline as they grow. Girls take on domestic tasks earlier than boys, and after age three, peer groups play a larger role. Recently, mission schools have introduced formal education, reshaping socialization. Inheritance is along along male lines, though unmarried individuals’ possessions may be distributed more broadly. [Source:Wulf Schiefenhövel, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Marriage is ideally arranged between suitable lineages, but such arrangements are often rejected because both partners may refuse them and love affairs are common. Marriages form through mutual gift exchange rather than bride-price. Most couples live virilocally, and some men practice polygyny. In the 1980s more than 10 percent of men had two wives and five percent lived permanently without wives. One woman was found living with two brothers. Pre-martial sex is allowed but married couples are expected to e faithful. Separation, divorce and remarriage are common. The abduction of wives for new marriages is not uncommon. ~

In the early 1980s Schiefenhövel noted that among the Eipo, boy’s genital play was met with amusement, in contrast to the little girl’s. He described a general picture of sexual tolerance, however in “many interviews with informants in which sexual topics were touched upon, the information provided led the interviewers to believe that homosexual acts, playful or “serious”, among male children…do not occur. On the other hand, this author did hear of male and female children “having had intercourse” in the grassland beside the village. Everyone laughed with good humour about this behavior; the children involved were neither reprimanded nor punished in any way”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Archive of Sexuality, sexarchive.info ]]

Eipo Life, Villages and Economic Activity

The main staple crop of the Eipo is sweet potatoes. They also raise several varieties of taro, cucumbers, greens, wild asparagus, bananas, sugar cane and collect a varieties of food from the forest. Men hunt small marsupials and snakes with dogs. Women collect frogs, snakes, lizards, spiders, other insests and larvae for food. Pigs are highly valued and raised primarily for ceremonial purposes. Many of their tools and weapons have traditionally been made of stone, wood and bone. They traditionally used few medicines other than pig fat and nettles. [Source: Wulf Schiefenhövel, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Eipo villages are small (30–250 people) and built in defensible locations. Prominent circular men’s houses—often with sacred functions—stand at the center or edge, while smaller family houses cluster nearby. Women use separate seclusion houses during menstruation, childbirth, and illness. Most houses have raised floors and central hearths, though they provide poor protection from cold. Dani architectural styles are spreading through mission influence.

The Eipo are skilled horticulturalists. Gardens range from steep slopes to wet flats that require ditching and mounding. Reliance on mission goods has grown in recent years. Material culture was simple, with stone, bone, and wooden tools still in use into the 1970s but now modern tools are typically used. Cooking is done in ashes, bamboo tubes, or earth ovens. Traditional trade supplied items they lacked—stone adzes from specialists, black-palm bow wood, feathers, and prized shells.

Labor is mostly shared, though some tasks are sex-specific: men build houses, fell trees, hunt, and slaughter pigs; women craft string bags and carry heavy loads; both work in gardens, with women handling the heavier share. Land is owned by individuals or clans, marked by planted boundary shrubs, and allocated to ensure access for all, though disputes are frequent and can lead to violence.

Damal

The Damal live in the highlands of Central Papua Province, mainly in the Beoga Valley along the Beogong River. Also known as the Damalme, they are closely related to the Delem and Amungme peoples, with Delem said to descend from Damal, Dani, and Wano ancestry. Oral traditions trace Damal origins to Mepingama in the Baliem Valley, through Kurima and Hitigima—where they first built thatched honai houses—before migrating west to Beoga and Ilaga. From these heartlands, groups later moved into Jila, Alama, Bella, Tsinga, Hoeya, Tembagapura, Aroanop, Timika, and Agimuga. [Source: Wikipedia, Stichting Papua Erfgoed]

Damal social organization is based on two exogamous moieties, Magaij and Mom, each composed of patrilineal clans—37 in Beoga and 8 in Ilaga. Clans support members in travel, bridewealth payments, and other obligations. Political leadership rests with a Nagawan/Nagwan, an achieved rather than hereditary role requiring economic skill, generosity, effective public speaking, and the ability to lead in warfare.

The Damal occupy multiple valleys rather than a single continuous territory. Some groups live in deep forested ravines on the southern slopes of the Central Plateau; others share plateau lands with neighboring peoples. In several regions, such as Upper Ilaga, they have long interacted with and absorbed West Dani settlers. Their society resembles other Mountain Papuan groups in using a dual organization structured around intermarrying clan pairs.

Economically, the Damal— and the Amungme—depend heavily on forest foraging alongside steep-slope gardening. They traditionally preferred taro (keladi) over sweet potatoes, using irrigation to maintain taro gardens before adopting sweet-potato methods from the West Dani. Ethnographers also note a distinct pattern of millenarian expectation: throughout the twentieth century, Damal groups engaged in ritual movements seeking collective transformation. These expectations shaped the rapid, widespread conversion to Christianity in the 1950s, which they interpreted through existing beliefs about deliverance.

Amungme

The Amungme live in the highlands of Central Papua. Also known as the Amung, Amungm, Amui, Amuy, Hamung, or Uhunduni, they number about 17,700 and live near the Damal. Most Aming live in Mimika and Puncak regencies, in valleys such as Noema, Tsinga, Hoeya, Bella, Alama, Aroanop, and Wa. The Amungme speak Uhunduni, which has several dialects. Amung-kal is used mainly in the southern areas, while in the north it is known as Damal-kal. They also maintain symbolic speech forms, Aro-a-kal and Tebo-a-kal, the latter reserved for sacred contexts. [Source: Wikipedia]

Traditional Amungme religion is animistic. They do not conceptualize deities as separate from nature; instead, spirits and the natural world are essentially the same. They view themselves as the eldest children of Nagawan Into, the creator, and as stewards of the world Amungsa. Leadership is not hereditary. The Amungme are known for their rich oral literature, especially songs that preserve and transmit cultural knowledge. Elders urge younger generations to record this tradition. Amungme musical performances often feature the pikol, a bamboo wind instrument that accompanies sung narratives.

The Amung subsist through shifting cultivation, supplemented by hunting and gathering, and they maintain a profound spiritual attachment to their ancestral lands, especially the surrounding mountains. This attachment has brought them into conflict with both the Indonesian government and Freeport-McMoRan, whose Grasberg mine—one of the world’s largest gold and copper mines—lies in the heart of Amungme territory. Mining operations have dramatically altered the landscape and attracted large numbers of migrants from elsewhere in Indonesia, including other Papuans, some of whom have attempted to settle on Amungme land. These developments have fueled long-running disputes over customary land rights in Timika.

Over the past 35 years, the Amungme have seen their sacred mountain cut away by the mine, and many have been caught in clashes between Indonesian security forces and Free Papua Movement fighters. Meanwhile, downstream Kamoro communities have endured massive pollution, with more than 200,000 tons of mine waste entering their rivers daily. These pressures have produced complex social and political tensions, leading to recurrent protests and at times violent crackdowns by Indonesian police or military forces.

See Separate Articles about the Freeport Mine:

FREEPORT MCMORAN GOLD AND COPPER MINE IN PAPUA, INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

PROBLEMS AT THE FREEPORT MINE: VIOLENCE, POLLUTION AND BRIBES TO THE MILITARY factsanddetails.com

Ekagi (Mee)

The Ekagi live in the west central highlands of Papua (West New Guinea) around the Paniai, Tage and Tigi lakes. Also known as the Kapauku, Ekari, Mee, Me and Tapiro, they have a reputation among other tribes as being traders but did not have contact with Europeans until 1938. In the old days, they used tools made from stone, wood, bamboo, bone and animal teeth. Their primary weapons are bows and arrows tipped with bamboo blades. Their currency was shells. [Source: Nancy Gratton and Ian Skoggard, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

The Ekagi language (Ekagi) is classified within the Ekagi-Wodani-Moni Family of Papuan languages. Most of the region where the Ekagi is above 1,500 meters (4,921 feet), and has five vegetation zones, including a fair amount of tropical rain forest. Rainfall is plentiful. The Ekagi have traditionally lived in longhouses with individual apartments for women and children and a men’s-house-style dormitory for the men. Their structures are elevated and have a place underneath for pigs. Sweet potatoes make up 90 percent of their diet and pig husbandry and trade is their primary economic activity. They also eat crayfish, dragonfly larvae, several types of beetles, frogs, bats and rats. Hunting and fishing doesn’t yield much. ~

The Ekagi are one of the larger ethnic groups in Papua. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 176,000. In the 1960s, the Ekagi population was estimated at about 45,000; in the 1990s, it was around 100,000. Although the Ekagi are generally treated as a single cultural group, there are variations in dialect and in social and cultural practice across Ekagi territory. The name "Ekagi" was given them by neighboring groups to the south, and the Moni Papuans, their neighbors to the north, call them "Ekari," but they call themselves "Me," or “Mee” which means "the people."

History: The Ekagi (who call themselves Mee, meaning “true human”) have lived as horticulturalists and regional traders for a long time, though little is known about their early history. Their oral traditions trace their origins to a place east of the Baliem Valley. A major trade route linking New Guinea’s south coast to the interior passed through their territory, connecting them with neighboring groups such as the Moni and Kamoro, with whom they traded using cowrie-shell currency (mege).

European explorers first encountered inland Ekagi communities during the 1909–1911 British Ornithologists’ Union expedition, which labeled some groups “Tapiro pygmies.” In 1934, Dutch pilot Frits Wissel reported large settlements around the Paniai, Tigi, and Tage lakes. Europeans variously called them Ekari or Kapauku, both exonyms. Direct Dutch contact began in 1938 with the establishment of a government post at Lake Paniai, abandoned during the Japanese occupation and reestablished in 1946 alongside returning missionaries.

Ekagi Religion and Culture

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 95 percent of Ekagi are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being five to 10 percent. The Ekagi believe in a creator god named Ugatame, who created mankind and illnesses and spirits to torment them. Ugatame dwells beyond the sky. The Ekagi believe that Ugatame created both the physical world and numerous spirits, which usually appear as shadowy figures in the forest and occasionally in dreams or visions. These spirits, as well as the souls of the dead, can be enlisted as helpers or guardians. [Source: Nancy Gratton and Ian Skoggard, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Religious Practitioners include shamans, who use spirit helpers for healing and protection, and sorcerers, who wield harmful magic. A feared figure is the ghoul, an older woman believed to be inhabited by a flesh-eating spirit; her condition is blamed on a sorcerer’s magic, which must be countered to stop her attacks. Illness is attributed to spirits or sorcery and treated by shamans through spells, plants, purification, or extraction of harmful matter.

Big events are celebrated with pig feasts, which sometimes go on for several days. Major ceremonies include the Juwo pig feast, an infrequent, months-long event with ritual housebuilding, nightly dances, and large-scale pig slaughter; the TAPA fundraising ceremony, which raises wealth for obligations like bride price or compensation payments; and the Dedomai pig market, a more secular meat-selling event. All serve as occasions for trade and loan agreements.

Death and Funerary Practices There is no concept of the afterlife. The souls of dead become spirits that can haunt the living at night. Death is believed to be caused by spirits or sorcery. The soul wanders the forest by day but returns at night to aid or avenge its kin. The dead have traditionally been buried with their heads exposed and covered with a box with a window that allows them to see out. Funerary practices aim to secure the soul’s protection: ordinary people are semi-interred with the head exposed, respected men are placed in tree houses, and wealthy leaders in elevated huts, while low-status individuals or enemies receive minimal rites.

Ekagi visual arts are limited, mainly to net bags and adornments. Dance and song are central, especially during pig feasts, featuring dances such as the waita tai and tuupe, and the ugaa, a performance in which sung solos can convey gossip, complaints, or marriage proposals.

Ekagi Family and Marriage

Ekagi households typically center on a nuclear family but often include additional relatives—either by blood or marriage—and their spouses and children. Wealthy or influential men may also have apprentices or political followers living with them, along with those followers’ families. The household forms the basic unit of residence, production, and consumption. The house owner serves as the nominal head, organizing work and ensuring cooperation among male members, though each married man retains full authority over his own wife or wives and children—authority that even the household head cannot override. Inheritance follows principles of primogeniture and patri-parallel descent. [Source: Nancy Gratton and Ian Skoggard, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Marriage ideally unites a young man with his mother’s brother’s daughter, though securing a substantial bride-price often outweighs making a preferred match. Divorce requires returning the bride-price. A girl’s mother may demand an exceptionally high bride-price to block an unwanted suitor. Elopements, while frowned upon, are not uncommon; families typically resolve them by negotiating a bride-price afterward. Courtship often takes place during pig feasts, when young people from neighboring villages gather to dance and meet potential partners. Premarital sex is discouraged because it may reduce a woman’s bride-price, but it is generally not punished; premarital pregnancy, however, is strongly condemned. In cases of divorce, children stay with their mother until about age seven, after which they join their father’s village. Polygyny marks a man’s wealth, as it requires paying multiple bride-prices. Widows are expected to remarry unless elderly or ill, but levirate marriage is not assumed.

Boys undergo no formal initiation rites. Around age seven, they traditionally move into the men’s house, where they learn the expectations of adulthood. Girls, after their first menstruation, spend two days and nights in semi-seclusion in a menstrual hut during their first two cycles. There they receive instruction from female relatives before adopting the bark-thong wrap worn by adult women. Children learn adult roles through both observation and directed training.

Ekagi Society and Kinship

Ekagi social relations are organized around families united by marriage and totemic taboos. One of the main goals of economic activity is attaining enough wealth for a bride price. Leadership positions are based on wealth measured in pigs, shells and wives. Traditionally, confederations formed from alliances of lineage groups. These sometimes were involved in feuds, raids and wars, which were triggered mainly to avenge the death of kin members and were fought mostly with bows and arrows. [Source: Nancy Gratton and Ian Skoggard, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

A Tonowi (headman) exercises authority through personal prestige and wealth, especially by granting or denying credit. Ekagi legal process is informal: the headman listens as disputes spread among kin, then intervenes before violence occurs, questioning all parties, gathering evidence, and delivering a persuasive judgment—often with emotional displays to secure acceptance.

Households are patrilocal units set up in the husband's community and up of two or three families. Each nuclear family manages its own production, childrearing, and discipline. About fifteen households form a village; one or more villages make up a sublineage or lineage led by a Tonowi. Rights and obligations are rooted in these patrilineal groups, whose members support one another, especially in assembling bride-price payments.

Clans are the central kinship units: named, patrilineal, totemic, and ideally exogamous (with marriages outside the clan). Several clans may form phratries sharing totemic taboos, and many clans are divided into moieties. Marriage ties link lineages into larger political confederations. Ekagi kinship terminology is largely Iroquois, distinguishing paternal and maternal relatives, affines and consanguines, and differentiating cross and parallel cousins based on the sex of the connecting links.

Ekagi Life, Villages and Economic Activity

Ekagi are known for their unique cultural practices, such as their bark clothing and preparing meals in treehouses using ingredients from the rainforest. Some of their cultural practices have been impacted by modern changes and external influences, including the introduction of new currency systems and the impact of modern medicine and infrastructure. [Source: Nancy Gratton and Ian Skoggard, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

An Ekagi village is a loosely organized cluster of about fifteen houses, typically home to around 120 people. There is no fixed layout—people may build wherever they choose, provided they hold the appropriate rights to the land. The core dwelling is the owa, a large elevated house with space underneath for keeping pigs. Inside, a plank partition divides the structure into two main sections: the emaage, or men’s dormitory, at the front, and the kugu, a set of individual “apartments” at the back, one for each woman and her children. When space in the owa is insufficient, additional small houses (tone) are constructed nearby.

Anthropologist Leopold Pospisil described the traditional Ekagi economy as a form of “primitive capitalism,” marked by individualism, wealth accumulation in cowrie-shell money, and status based on material wealth. Today, Subsistence centers on sweet potatoes—grown on about 90 percent of cultivated land—and pig husbandry, with pigs serving as a primary source of income. Other crops (greens, sugar cane, bananas, taro) supplement the diet, along with crayfish, insects, frogs, rats, and bats. Upland gardens use extensive cultivation and long fallows, while valley gardens use intensive raised-bed systems; most households maintain both.

Manufacturing is limited and largely non-specialized, including bark-fiber net bags, clothing, stone tools, bamboo knives, and simple weapons. Trade occurs within and beyond the region, especially with coastal Mimika, focusing on pigs and salt. Shell money, pigs, and credit dominate transactions; barter is minor. All food distributions create obligations of repayment, and shell currency is used to pay shamans, surgeons, and hired labor.

Labor is strongly divided by gender. Men handle major agricultural planning, heavy work, certain crops, construction, and all large-game hunting. Women plant and weed sweet potatoes and other crops, gather small aquatic animals, and tend pigs and chickens (though only men slaughter them). Women weave utilitarian net bags, while men produce decorative ones. Land is privately owned by male household heads, who grant use-rights to their families. Sons inherit land, and owners hold full rights of use, transfer, and alienation—even forest tracts are individually owned.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Peter Van Arsdale and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Geographic,, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Encyclopedia.com, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025