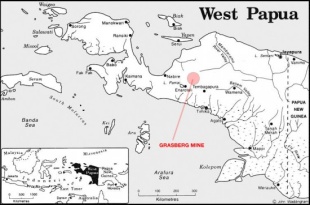

GRASBERG GOLD AND COPPER MINE

The Grasberg mine in Papua, Indonesia, is the world’s second-largest gold mine. Discovered in 1988, the operation includes the Grasberg open pit and four underground mines—DOZ, DMLZ, Big Gossan, and Grasberg Block Cave (GBC)—as well as the undeveloped Kucing Liar deposit. Open-pit mining began in 1990 and was scheduled to wind down by the end of 2019, while ore production from the GBC underground mine began earlier that same year. In 2018 the operation produced 2.69 million ounces of gold and milled about 178,100 tonnes of ore per day. Ongoing underground expansion aims to increase output to roughly 240,000 tonnes per day by 2022. [Source: Mining Technology]

The Grasberg Block Cave Mine is the world's sixth largest copper mine according to Global Data. An underground brownfield mine owned by Mining Industry Indonesia, it produced an estimated 41,853,000 tonnes of copper in 2023. The mine will operate until 2041.

As of the 1990s, the world's largest known gold deposit and the world' third largest copper reserves were located on 13,000 foot-high Grasberg Mountain in south central Papua not far from 16,024-foot Puncak Jaya, the highest mountain in Oceania, Indonesia and Southeast Asia, and the only one between the Andes and the Himalayas that has glaciers. There are also large deposits of silver in the area. [Source: Mark Frankel, Newsweek, December 18, 1995]

RELATED ARTICLES:

PROBLEMS AT THE FREEPORT MINE: VIOLENCE, POLLUTION AND BRIBES TO THE MILITARY factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

LORENTZ NATIONAL PARK AND THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN IN OCEANIA factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHERN PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF WEST NEW GUINEA — EIPO, DAMAL, EKAGI — AND THEIR HISTORY, LIFE AND SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Owners of the Grasberg Mine

The Grasberg mine is operated by Freeport Indonesia (PTFI). The company is jointly owned by the Indonesian government and the American company Freeport-McMoRan. The Indonesian government, through PT Mineral Industri Indonesia (MIND ID) and PT Indonesia Papua Metal & Mineral (co-owned by MIND ID and the Papua provincial government), holds 51.23 percent while Freeport-McMoRan owns 48.77 percent.. [Source: Wikipedia]

Before 2018, Freeport-McMoRan controlled 90.64 percent of PTFI, including a 9.36 percent share held through its subsidiary PT Indocopper Investama. During negotiations to extend its mining permit, Indonesia secured a majority stake (51.23 percent), and Indocopper was renamed PT Indonesia Papua Metal & Mineral. As a result, Freeport-McMoRan ceded its position as the world’s largest copper producer, leaving Chile’s state-owned Codelco in the lead. Indonesia also extended Freeport-McMoRan’s mining lease from its 2021 expiry to 2041.

Freeport-McMoRan Inc., often called Freeport, is an American mining company based in the Freeport-McMoRan Center, in Phoenix, Arizona. It was previously based in New Orleans . The company is the world's largest producer of molybdenum and a major copper producer as well operating the world's largest gold mine, the Grasberg mine in Papua, Indonesia.

History of the Grasberg Mine

In 1936 Dutch geologist Jean Jacques Dozy joined an expedition to Mount Carstensz (now Puncak Jaya), where he noted unusual black-and-green rock formations and mapped rich copper-gold deposits. Working for the Nederlandsche Nieuw Guinea Petroleum Maatschappij (NNGPM), he filed a report in 1939 describing the Ertsberg (“ore mountain”). [Source: Wikipedia]

Forgotten for two decades, the report resurfaced in 1959 when Jan van Gruisen of the East Borneo Company searched for geological studies on western New Guinea. Although unrelated to nickel, the report prompted him to request an exploration concession. Van Gruisen later mentioned it to Forbes Wilson, vice president of Freeport Minerals, who immediately saw its value. Wilson organized a difficult six-week expedition in 1960 that confirmed extensive copper mineralization, prompting Freeport’s investment.After Dutch New Guinea was transferred to Indonesia in 1963, Ertsberg became the first major project under Indonesia’s 1967 foreign-investment laws. Built at 4,100 meters in extremely remote terrain, the mine required $175 million in capital—far beyond Indonesia’s capacity at the time—and included a 116-km road and pipeline, a port, airstrip, power plant, and the town of Tembagapura.

The Grasberg mine began production in the 1970s in the early years of the U.S.-backed Suharto dictatorship. Freeport has access to nine million acres of land, an area one and half times the size of Vermont. About 1.24 million acres is taken up by the mine. The mine began shipping ore in late 1972 and officially opened in 1973, later expanding with Ertsberg East in 1981. Ore was moved by steep aerial tramways, dropped 600 meters for processing, and pumped as slurry through a 166-km pipeline to the port at Amamapare for drying and export. As of the mid 1990s the company had spent $3 billion to develop the mine and extract its minerals and was the largest single American investor in Indonesia, with a market capitalization of $5 billion, and the country's most profitable business, making more than $1 million a day.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the Freeport Gold Mine was the world’s largest gold mine and the world's second largest copper mine . In the 1990s, everyday about $7.2 million worth of gold, copper and silver was extracted from the Grasberg mine. The refined metal harvested every year at that time was worth about $2 billion. As of 2009, Freeport workers numbers around 20,000 excluding on site family members. In 1995 the 60,000 people linked with the mine—employees and their families— lived on a compound carved out of the jungle with American-style shopping centers.

Freeport had ambitious plans to turn Grasberg into the world's biggest underground mining complex after 2016 when its open pit operations was due to end. In 2013, open pit mining accounted for two-thirds of production. In the early 2010s, open-pit mining at Grasberg normally produced around 140,000 tons of copper ore a day, while underground operations yielded 80,000 tons. Freeport said it expected production to reach 1.1 billion pounds of copper and 1.2 million ounces of gold in 2013, up 54 percent and 31 percent over 2012 figures, respectively, as mining moves into higher ore grades. [Source: Yayat Supriatna, Reuters, May 31, 2013]

Mining Operation at the Grasberg Mine

The Grasberg mine straddles a mineral-rich ridge of peaks pushed up by a collision between the Pacific and Australian tectonic plates. The total deposit, one of the world's richest, is worth at least $100 billion. The mine has proven reserves of 46 million ounces of gold, according to the company's 2004 annual report. In 2005, Mining International, a trade journal, called Freeport's gold mine the biggest in the world.

Grasberg includes a completed 2.4-kilometer-wide open pit, three active underground mines (Grasberg Block Cave, Deep Mill Level Zone, and Big Gossan), and four concentrators. It is a high-volume underground operation, producing and milling more than 72 million tonnes of ore in 2023. Ore is crushed at the mine and sent to the milling complex, where it is ground and processed by flotation. The concentrator facility—one of the world’s largest—handled about 240,000 tonnes of ore per day in 2006.

Freeport says there is enough gold ore in Grasberg to keep it going until 2040. As of the early 2010s, the mine employed just over 24,000 contract and non-contract workers, with a union representing about 18,000 of the workers. [Source: Michael Taylor, Reuters, May 14, 2013]

Mining at the Freeport Mine

The Grasberg Mine is located on the top of a mountain. To get to it you need to pass through two tunnels and then climb an incredibly steep road that is so dangerous drivers need a special permit to traverse it. The open-pit mine will be more than two miles across at the end of its working life, sometime around 2016.

The ore is dug up with huge shovels and loaded onto trucks that coat $2 million a piece and moved to a processing plant that crushes and chemically process the ore into Copper–gold concentrate, which is transported as slurry through pipelines 120 kilometers (75 miles) to the coast the port of Amamapare, where it is dewatered and shipped to global smelters. A coal-fired power station at the port supplies energy to the operation; it is scheduled to be replaced in 2027 by a 265-MW LNG-fueled combined-cycle plant. The work continues 24 hours a day, seven days a week. More than 200 tons of ore is pried loose from the rock every day.

Describing the mining process in the 1990s, Thomas O'Neill wrote in National Geographic, "Shivering in the cold wind...I watched trucks with tires ten feet high haul out ore that would be processed into a gray concentrate of copper, gold and silver. The mix, piped in a slurry from down the mountain to the private seaport of Amamapare, is dried and shipped to smelters round the world. Everything is jumbo size: the workforce of 17,000; the gold, an estimated 40 million ounces, the single biggest gold reserve in the world; the copper deposits 28 billion pounds." [Source: Thomas O'Neill, National Geographic, February, 1996 ☼]

Freeport’s Wild West Company Enclave

The Freeport operation is so big that the company has almost created its own ministate. Tembagapura, or "Copper Town" is home ot many of the mines employees. Located halfway up the mountain and identified with a sign that bears the Freeport logo, it features air-conditioned markets with a wide variety of American goods and modern apartments and recreation facilities.

Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner wrote in the New York Times, “Papua's extreme remoteness and the company's long ties to the Indonesian government have given Freeport exceptional sway over a 21st-century version of the old company town, built on a scale unique even by the standards of modern mega-mining. "If any operation like this was put forward now, it wouldn't be allowed," said Witoro Soelarno, a senior investigator at the Department of Energy and Mineral Resources, who has visited the mine many times. "But now the operation exists, and many people depend on it." [Source: Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner, New York Times, December 27, 2005 -]

Near Tembagapura on the plains below the mountain is Timika, an ugly town full of prostitutes, bars, gambling halls and people in ragged jeans and T-shirts. It is occupied mainly by poor Papuans who have come to the area to seek work. The Indonesian police and military have a strong presence here. Before the arrival of the mine the plains around Timika was unpopulated. In the 1990s it had 30,000 people, a Sheraton hotel and an airport. By the mid 2000s, there were 100,000 people there.

The Aghawagon Valley and the area around the Freeport mine is the homeland of Amungmen people. Since the opening of the mine they have gotten in disputes with the more numerous Dani migrants, who have come to the area looking for work. In the 1990s nine people were killed in one altercation.

History Freeport’s Relationship with the Indonesia

Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner wrote in the New York Times, “For years, to secure Freeport's domain, James R. Moffett, a Louisiana-born geologist who is the company chairman, assiduously courted Indonesia's longtime dictator, President Suharto, and his cronies, having Freeport pay for their vacations and some of their children's college education, and cutting them in on deals that made them rich, current and former employees said.[Source: Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner, New York Times, December 27, 2005 -]

“It was a marriage of mutual convenience. As Freeport prospered into a company with $2.3 billion in revenues, it also became among the biggest - in some years the biggest - source of revenue for the government. It remains so. Freeport says that it provided Indonesia with $33 billion in direct and indirect benefits from 1992 to 2004, almost 2 percent of the country's gross domestic product. With gold prices hitting a 25-year high of $540 an ounce in December 2005" the company paid the government $1 billion in 2005. -

“With Suharto's ouster in 1998, after 30 years of unchallenged power, Freeport's special place was left vulnerable. But its importance to Indonesia's treasury and its carefully cultivated cocoon of support have helped secure it against challenges from local people, environmental groups, and even the country's own Environment Ministry. Letters and other documents provided to The Times by government officials showed that the Environment Ministry repeatedly warned the company since 1997 that Freeport was breaching environmental laws. They also reveal the ministry's deep frustration.

“At one point last year, a ministry scientist wrote that the mine's production was so huge, and regulatory tools so weak, that it was like "painting on clouds" to persuade Freeport to comply with the ministry's requests to reduce environmental damage. Since Suharto's ouster, Freeport employees say, Mr. Moffett's motto has been "no tall trees," a call to keep as low a profile as possible, for a company that operates on an almost unimaginable scale.

Good Things Done By Freeport McMoRan in Papua

Freeport is the largest employer in Papua. It provides half of Papua’s gross domestic product. Between 1992 and 1998 it provided the Indonesian government with $1.27 billion from divided royalties and corporate taxes. As of August 2000, 20 percent of the 6,000 person workforce was Papuan (including 100 Papuans in supervisor roles), 4,000 students have been given scholarships. At that time about 30 percent of the 18,000 people that were employed by the mining operation were Papuans.

Freeport McMoran is the largest foreign taxpayer in Indonesian. It paid more than $1 billion in taxes between 1989 and 2002 and cotributed $1 billion a year to the Indonesian economy. The company has spent more than $160 million on regional development since 1992, most of it on roads and tunnels and cable systems. It also spends over $16.5 million (about 1 percent of its revenues) annually on schools, medical care and other programs for the people of Papua.

Freeport claims that its health centers treat more than 5,000 patients a month free of charge, provides drinking water by digging deep freshwater wells, employs 14,000 Indonesians, and is helping Indonesian animals such as the Sumatran Tiger, Komodo dragon and barasingha.

A Freeport-sponsored anti-malaria program has cut the rate of infection of that disease from 80 percent of the population to 10 percent. The company runs a $3.5 million environmental lab and $4 million 75-bed hospital. The company even sponsors a rugby teams called the Kotekas (named after the penis gourds worn by many tribesmen).

Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner wrote in the New York Times, After riots in 1996, “Freeport began dedicating 1 percent of revenues annually to a development fund for Papua to pay for schools, medical services, roads - whatever the people wanted. The company built clinics and two hospitals. Other services include programs to control malaria and AIDS and a "recognition" fund for the Kamoro and Amungme tribes of several million dollars which, among other things, gives them shares in the company as part of a compensation package for the lands Freeport is using. By the end of 2004, Freeport had spent $152 million on the community development fund, the company said. [Source: Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner, New York Times, December 27, 2005 -]

“S. Prakash Sethi, head of the International Center for Corporate Accountability, commended Freeport for commissioning the report on the company's development programs, saying that it was the first mining company to do so. The report, which was released in October, concluded that the company had successfully introduced a human rights training program for its employees and had doubled the number of Papuan employees by 2001. The company was poised to double the number of Papuans in the work force again by 2006, the audit said.”-

Bad Things Done By Freeport McMoRan in Papua

Many local activists are resentful because Freeport earns billions of dollars in profit from Papua's natural resources while the people remain overwhelmingly poor. Freeport has earned millions of dollars from its mine in Papua. The Indonesia government has collected money from the operation, but hardly any money has trickled down to the Papua people, according to Viktor Kausiepo, a Papuan activist living in exile. The company has leveled a mountain sacred to indigenous people and cut down their forest and fouled their streams. The Japanese are chopping the trees into bits for paper and chopsticks.

Many local people don’t like Freeport-McMoRan Copper. They claim the company has destroyed sacred lands, ravaged the environment and failed to share their wealth with local communities. Amunme and Komoro people have been displaced by the mine and, many feel, were not adequately compensated. Many Papuans believe that Freeport could spend much more than money than it does to aid the local population. Management of Freeport counters it is a business and it is not its responsibility to provide things that should be provided by the government.

The Freeport mine has been blamed for high levels of alcoholism, destruction of indigenous cultures, the dispossession of native lands, and the influx of Indonesians to Papua. Some local people claim Freeport drove them off their land. Activist sclaim that Papuans make only 10 percent of the workforce and most of the jobs go to Indonesian from other parts of the archipelago. Freeport agrees it has not hired many Papuans but argues this is the case because the skill levels and education of the local people are very low.

Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner wrote in the New York Times, Thom Beanal, an Amungme tribal leader, “says the combined weight of the Indonesian government and Freeport has left his people in bad shape. Yes, he said, the company had provided electricity, schools and hospitals, but the infrastructure was built mainly for the benefit of Freeport.” Mr. Beanal said he told Freeport’s chairman that the flood of money from the community fund was ruining people's lives.When the company arrived, he noted, there were several hundred people in the lowland village of Timika. Now it is home to more than 100,000 in a Wild West atmosphere of too much alcohol, shootouts between soldiers and the police, AIDS and prostitution, protected by the military.[Source: Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner, New York Times, December 27, 2005 -]

Mr. Beanal, a vocal supporter of independence for Papua, has fought the company from outside and inside. In 2000, he decided that harmony was the better path, and joined the company's advisory board. In November 2005, he and other Amungme and Komoro tribesmen met with Mr. Moffett at the Sheraton Hotel in Timika and told him the flood of money from the community fund was ruining people's lives. Mr. Beanal said he was increasingly impatient with the presence of the soldiers and the mine. "We never feel secure there," he said. "What are they guarding? We don't know. Ask Moffett, it's his company." -

Indonesian Military and Freeport McMoRan

Freeport McMoRan hires the Indonesian military to provide protection and keep trespassers and local people off their land. As is true with Exxon Mobile in Aceh, some of the soldiers hired by the company have been involved in violence against local people. The highly militarized zone around the mine is off limits to foreign journalists. More soldiers arrived after a peace agreement was hammered out in Aceh in 2005 and the government is redeployed soldiers to Papua in a move, according to the New York Times, “ to defeat the growing enthusiasm for independence, once and for all, and to watch over the province with the world's biggest gold mine.: After a wave of deadly shootings in 2009, Indonesia began deploying police special forces in the area.

The Indonesian government depends heavily on the Freeport’s Grasberg mine for tax revenue. To secure this strategic asset, Jakarta maintains a large military presence in the region. While Freeport has no formal authority over these forces, it provides them with logistical support such as food, housing, and transport. A dense network of political, military, and economic relationships has long shielded Freeport from challenges posed by labor groups, Papuan activists, and environmental critics. Operating under minimal regulation and backed by state security forces, the company has effectively created a protected enclave around its operations.

The Indonesian military—known for financing itself through both legal enterprises and illicit activities—used its presence at Grasberg to expand its influence in Papua. As Freeport’s security needs grew, the company’s operations became increasingly intertwined with military interests, with soldiers often commandeering company vehicles and infrastructure.

Freeport has disclosed paying millions of dollars to Indonesian security forces—$4.7 million in 2001 and $5.6 million in 2002—without specifying how the funds were used or where they were deposited. The company defends these payments as consistent with the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, which allow natural resource firms to help cover security costs for their facilities.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Freeport McMoRan

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025