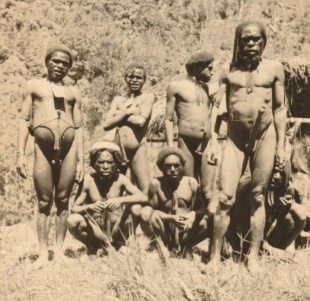

DANI

Dani is a somewhat pejorative term used by outsiders to describe groups around the Baliem Valley, the main tourist area of Papua. Also known as the Akhuni, Konda, Ndano and Pesegem and sometimes spelled Ndani, they have traditionally lived in circular thatch-roof huts and subsist primarily on sweet potatoes. The different Dani groups have different languages customs and styles of clothing. Some are former Stone-Age cannibals. [Source: Karl Heider, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Oceania”edited by Terence Hays, (G.K. Hall & Company, 1996) ~]

Known as the “gentle warriors”, the Dani have only recently emerged from the Stone Age. Yet with their simple tools of stone and bone, they managed to sculpt green fields that hug the hills of the Baliem Valley, where they grow root crops, and raise pigs. They have also built outposts and lookout towers to defend their valley from hostile tribes. Because the land is fertile soil and crops are raised with agricultural skills, the Dani together with the sub-tribes of the Yali and the Lani have made the Baliem Valley the most populous area in Papua, living scattered in small communities near their gardens among the steep mountain slopes. Today, they mostly cultivate bananas, taro, yams, ginger, tobacco and cucumbers. Pigs are greatly valued. The men's and women's huts (locally called the honai) have thick thatched roofs, which keep the huts cool during the day and warm during the cold nights.

The Dani are one of the most populous highland societies and are widely recognized in Papua, in part because of the many tourists who visit the Baliem Valley. The term Ndani—meaning “people of the east”—originally referred only to Lani groups living east of the Moni. Early outsiders misunderstood the name as applying to all valley inhabitants. Although the people call themselves Hubula (also spelled Huwulra, Hugula, or Hubla), they have been known internationally as “Dani” since the 1926 Smithsonian Institution–Dutch colonial expedition led by Matthew Stirling, which encountered the Moni and adopted their usage. [Source: Wikipedia]

RELATED ARTICLES:

LIFE OF DANI PEOPLE OF WESTERN NEW GUINEA: SOCIETY. FOOD, SEXUALITY factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF WEST NEW GUINEA — EIPO, DAMAL, EKAGI — AND THEIR HISTORY, LIFE AND SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

BALIEM VALLEY: HISTORY, PEOPLE, TRAVEL, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN PAPUA AND THE BIRD'S HEAD (VOGELKOP) OF NEW GUINEA factsanddetails.com

NORTHWEST PAPUA AND THE BIRDHEAD OF NEW GUINEA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

Dani and Baliem Valley Groups

There are approximately 200,000 to 400,000 Dani people living in the Baliem Valley and surrounding areas of Western New Guinea. The Dani are not a single, homogenous group. The Dani population is spread across different sub-groups, such as the Upper Grand Valley Dani and Lower Grand Valley Dani. The discrepancy in Dani population numbers mainly has to do with what defines a Dani and whether or not Lani (Western Dani) are Dani. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project in the 2020s: 1) the Lani (Western Dani) population was 275,000; 2) the Lower Grand Valley Dani population was 20,000; 3) the Upper Grand Valley Dani population was 29,000; 4) the Mid Grand Valley Dani population was 79,000.

The Baliem valley itself is home to roughly 100,000 residents, including Dani groups, with roughly 20,000 in the lower valley, 20,000 in the upper valley and 50,000 in the central section. West of the Baliem Valley live around 180,000 Lani people, who were long misidentified as “Western Dani.” In everyday usage, however, the name “Dani” is often applied broadly to all inhabitants of the valley and its surrounding highlands, resulting in their frequent conflation with neighboring groups such as the Lani to the west; the Walak to the north; and the Nduga, Mek, and Yali peoples to the south and east. [Source: Wikipedia]

Grand Valley Dani of the upper Baliem River and the Western Dani are the largest Dani groups. The Eastern Dani are known as the Jale. They tend to be small and have traditionally lived in rougher terrain. They average only 4 foot nine in height and have Negroid feature but sometimes have green eyes and reddish blonde hair. The highlands where they live is covered by jungle and sharp rocks. It sometimes can take days just to cover a few miles. ~

Baliem Valley — Where the Dani Live

Baliem Valley (accessible by plane from Jayapura) is the main tourist destination in Papua and the most accessible access point to the Papua interior. Situated in the middle of Papua, it is central highland, tableland valley roughly 70 kilometers (45 miles) long and 16 to 31 kilometers wide (10 to 19.5 miles) and covering an area of 1272 square kilometers (491 square miles). A narrow paved road runs along the length of the valley, which is filled with fertile green fields, canals and forests and framed by terraced mountains and they in turn are surrounded densely forested mountains. The Baliem River drops more that 1500 meters in less than 50 kilometers as it heads south.

A stunningly beautiful place, the Baliem Valley is situated in the mountains of central Papua at an altitude of 1,600 meters and hemmed in by steep green mountain walls. The highest mountains are around 2,400 metrs high. It is cut by the Baliem river, which has its source in the northern Trikora mountain, cascading into the Grand Valley, to meander down and further rushing south dropping to become a large muddy river that slowly empties into the Arafura Sea.

The various Dani groups live in and around the Baliem River region, roughly between 4° S and 138°–139° E. Their largest concentration is in the BaliemValley of the Baliem. To the north and west, in the upper Baliem and nearby drainage systems, are the Western Dani. Other Dani communities are found throughout the surrounding mountainous terrain, from about 900 to 1,800 meters (2,952 to 5,905 feet) above sea level. The largest non-Dani presence in the region is in Wamena, the Indonesian administrative center, a town of around 5,000 people at the valley’s southern end.

See Separate Article: BALIEM VALLEY factsanddetails.com

Dani Languages

The half-dozen languages and dialects of the Great Dani Family are related to other Non-Austronesian language families of the Papuan Highlands Stock, which belongs to the Trans-New Guinea Phylum. The main Dani groups speak their own language or dialect. The Western Dani speak Western Dani. The Lower Grand Valley Dani speak Lower Grand Valley Dani. Upper Grand Valley Dani speak Upper Baliem Valley. Mid Grand Valley Dani speak Mid Grand Valley Dani.

Linguists identify several subgroups within the Dani or Baliem Valley languages, including Wano, Nggem, and Central Dani, as well as the Grand Valley Dani languages, which encompass Lower-Grand Valley Dani (about 20,000 speakers) and the closely related Hupla language, Mid-Grand Valley Dani (about 50,000 speakers), and Upper-Grand Valley Dani (about 20,000 speakers). Also included are Lani (or Western Dani), spoken by roughly 180,000 people along with the Walak language, and the Ngalik group, which comprises Nduga, Silimo, and the Yali dialect cluster. [Source: Wikipedia]

Dani languages distinguish only two basic color categories: mili, referring to cool or dark hues such as blue, green, and black, and mola, referring to warm or light hues such as red, yellow, and white. This feature has attracted extensive research interest from cognitive psychologists, including Eleanor Rosch, who explored the relationship between language and thought.

Dani History

Little archaeological work has been done in the Dani area so it is unclear when the area was first settled. The earliest recorded contact with Dani-speaking populations occurred in October 1909, when the Second South New Guinea Expedition led by Hendrikus Albertus Lorentz encountered a small Nduga group presenting themselves as the Pesegem and Horip tribes south of Puncak Trikora. Substantial contact with the populous Western Dani (Lani) took place in October 1920, during the Central New Guinea Expedition, when a team of explorers stayed for six months in the upper Swart River Valley (now the Toli Valley of Tolikara Regency). [Source: Wikipedia]

The Dani remained largely unknown to the outside world until the 1930s. When explorers discovered a Dani tribe in 1938 they had no metal tools. They used wooden spears, bows and arrows and stone tools. The first permanent contacts were not made until the 1950s. Michael Rockefeller had been with the Dani during the last great Dani tribal war. In the 1960s the Dutch government launched a program of pacification that was continued by the Indonesian government. For more details see the BALIEM VALLEY article factsanddetails.com

The first outsider to "discover" the Baliem Valley was American Richard Archbold, who, in 1938 from his seaplane, suddenly sighted this awesome valley dotted with neat terraced green fields of sweet potatoes, set among craggy mountain peaks. The first time the outside world really heard about the Baliem Valley was after a plane crashed there in 1945 and the survivor returned with incredible stories of what they saw there as if it were an equatorial Shangri-La.. Dutch missionaries arrived in 1954 and established the post of Wamena two years later. The first Westerners to live among the Dani — with the Lani of Kanggime in Tolikara — were missionaries John and Helen Dekker, under whose ministry the local Christian population eventually grew to about 13,000.

As part of a Harvard–Peabody expedition, filmmaker Robert Gardner documented life in the Kurulu and Wita Waya districts of the Baliem Valley beginning in 1961. His 1965 film Dead Birds emphasizes themes of death and the symbolic association of people with birds in Dani cosmology. “Dead birds” or “dead men” refer to weapons and ornaments taken from enemies during battle — trophies displayed during the two-day victory dance (edai) after a killing.

From 1977 to 1978, during the Papua conflict, the Indonesian army launched a military campaign in the region. The campaign became known as the Baliem Valley Massacre due to the numerous human rights abuses and attacks on civilians that occurred during it. The campaign left at least 4,146 people dead, though witness statements suggest the death toll is closer to 26,000.

The transmigration program (Transmigrasi), in which settlers from Java were resettled in New Guinea and elsewhere, and the Free Papua separatist movement have had relatively little direct effect on the Dani.

Dani Revenge Wars and Cannibalism

Traditional Dani revenge warfare was carried out to settle grievances, honor ancestral spirits, and restore good fortune. Until the 1960s, conflict between alliances was widespread throughout the Grand Valley. Each alliance was typically at war with one or more neighbors, and hostilities erupted whenever unresolved disputes grew too numerous. A single war could continue for a decade, gradually fading only when the original cause of conflict was forgotten. As tensions eased, alliances that had accumulated internal resentments sometimes broke apart and reorganized, creating new alignments. While confederations tended to remain relatively stable, the alliances within them shifted over time. [Source: Karl Heider “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Oceania”edited by Terence Hays, (G.K. Hall & Company, 1996)]

The prolonged nature of these conflicts stemmed from their ritual phase. Once a killing occurred, it was believed that the victim’s ghost demanded vengeance. Because opposing sides shared the same cultural framework and spirit beliefs, retaliatory killings continued in a cycle of reciprocal violence. During the ritual phase, large formal battles alternated with surprise raids and ambushes, occurring roughly once every two weeks. Major battles could draw as many as a thousand armed men to a designated battlefield for several hours, while raids involved small groups slipping across no-man’s land to strike an unsuspecting enemy.

Wars typically began with a brief, secular outbreak of violence unrelated to ghost appeasement. Alliances or confederations sometimes turned suddenly on former partners, launching surprise attacks on villages and killing men, women, and children. After such an assault, alliances would fragment and withdraw, leaving behind a kilometer-wide no-man’s land. This abandoned zone became the setting for the ritual battles that followed. By the 1960s, Dutch and subsequently Indonesian authorities succeeded in suppressing these formal battles, although sporadic raids and skirmishes persisted in more remote parts of the valley.

Most ritual battles caused few casualties. However, surprise attacks could be devastating, occasionally destroying entire villages and killing hundreds. The Dani also engaged in what they termed “nothing fighting,” small-scale confrontations with little intention of causing harm. The Indonesian government later mounted a largely successful effort to eliminate revenge warfare altogether, replacing it with mock battles staged during cultural festivals. Even so, fighting has sometimes resurfaced. A clash between the Wollesi and Hitigima districts in 1998 left 15 people dead, and other incidents of tribal conflict were reported in the 1990s.

Cannibalism has also been reported among the Dani. Jale believed that by eating an enemy his soul was swallowed and annihilated and his vital energy passed on to the man that ate him. The liver and heart were the most sought after pieces from a courageous hunter, the brains of wise men were praised and the legs of fast runners were believed to pass on their attribute to the person eating them. part. Some scientist believe that in the absence of many game animals, human flesh was also eaten as a source of protein. [Source: "Endangered People" by Art Davidson]

Dani Religion

The Dani have traditionally been animists who believed in local gods and water spirits. Particular attention was given to the restless ghosts of the recently deceased. A great effort was made to ensure they were placated or kept far off in the forest so they didn’t cause illnesses, troubles or create imbalances, which may or may not be rectified by men with special powers. Dani also believe in local land and water spirits. Islam, the majority religion in Indonesia, made little headway among the Dani as it was unable to cope with Dani pigs. [Source: Karl Heider, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Oceania”edited by Terence Hays, (G.K. Hall & Company, 1996)]

In the 1950s a cargo cult swept through the area followed by a wave of Christian missionaries. Many Dani have converted to Christianity.According to the Christian-group Joshua Project: 1) 90 percent of Western Dani are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 10 to 50 percent; 2) 85 percent of Lower Grand Valley Dani are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 10 to 50 percent; 3) 80 percent of Upper Grand Valley Dani are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 5 to 10 percent; 4) 85 percent of Mid Grand Valley Dani are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 5 to 10.

In the 1990s, journalist Thomas O'Neill observed a Sunday sermon attended by several hundred Dani swaying as if in a trance as a Dani deacon in an open-necked shirt shouted out: "On earth your grass may dry out. Your river may dry out. But in heaven it is always good. There is no fighting. You don't have to hunt or garden. Everything good comes to you." [Source: Thomas O'Neill, National Geographic, February, 1996 ☼]

Dani Funerals and Ceremonies

The Dani have traditionally believed that the soul-like “edai-egen” resides below the sternum and develops about the age of two. Serious illness causes it retreat to the backbone. Curing ceremonies to get it to return to its original position. Death is believed to be caused by magic or witchcraft At death the edai-egen becomes a ghost that must be appeased so it goes into the forest where it can cause no harm. As an expression of grief women often cover themselves in mud or clay.

The dead are usually cremated but sometimes mummified. Some mummies are 200 years and brought for tourist who pay to see them and photograph them. After arriving at a village 12 miles from Wamena, Marvin Howe wrote in the New York Times: "The village elders...brought out their dearest treasure: the smoked mummy of a former paramount chief. It was a hideous hunched figure with huge gaping eyes and mouth and would have done well in a horror film."

Many ceremonies have traditionally been associated with warfare and placating ghosts. Warfare itself has been described as a ceremony to placate ghosts. During times of war there were frequent ceremonies, including cremation ceremonies for people who died in battle. In these ceremonies the fingers of girls were sometimes chopped off as sacrifices to the ghosts of the dead people. Friends of the dead sometimes chopped of the tip their fingers or part of their ear as an expression of grief. The custom of chopping off body parts is now banned. These ceremonies as well as marriage and funeral ceremonies were often capped off by a big pig feast.

Yali

The Yali are one of the major tribal groups of the Baliem Valley, living primarily in Yalimo Regency, Yahukimo Regency, and the surrounding mountainous regions is the eastern part of the valley. In both the Yali and Dani languages, the word yali means “lands of the east,” which became the name of the people who live there. Another explanation traces Yali to ya (“path”) and li (“light”), meaning “people of the eastern sunrise,” with Yalimu (“place of the Yali”) formed by adding -mu. A second origin story links the name to Yeli, a mythical being whose body created all living things and who taught the Yali their customs before departing westward; his name is said to have gradually evolved into Yali. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Yali are related to the Dani and were once described as "solidly embedded in the Stone Age." They were cannibals and used cowrie shells as currency and stone tools before they converted to Christianity begnning in 1975. Now they use steel machetes and more modern tools. Reports of cannibalism persisted until the 1970s, after which missionaries helped end village feuds and discouraged warfare, ancestor worship, and older ritual practices. In 1968, Yali tribesmen killed and ate two missionaries who had destroyed villages fetishes. In the 1970s Yali tribesman killed and ate a mission preacher and a dozen of his assistants. The journalist Thomas O'Neill asked a teacher in a Yali village what would happen if he stole one of the headman's pigs. "Oh, he'd probably kill you," the teacher told him, "but at least he wouldn't eat you anymore." [Source: Thomas O'Neill, National Geographic, February, 1996 ☼]

Yali territory stretches from the Ubahak River in the east to the Sibi, Yahuli, and Podeng Rivers in the west. The main population centers are Anggruk and Kosarek, both extremely remote and accessible mainly by small aircraft; reaching villages still requires hours of walking. Collectively, these lands are known as Yalimu (also spelled Yalimo). The Yali are bordered by the Hubula (Dani) to the west, the Lani to the northwest, the Kem and Walak to the north, other Mek groups and the Kimyal to the east, and the Momuna to the south.

Yali Subgroups and Religion

The Yali are commonly divided into two major groups: 1) Yali (Mo) – mostly in Yalimo Regency; linguistically related to the Dani (Ngalik-Nduga branch); and 2) Yali Mek – mostly in Yahukimo Regency; linguistically connected to the Mek peoples. Each group is further divided into sub-groups with their own dialects: 1) Yali in Yalimo: A) Yali Abenaho or Pass Valley (Yali); B) Yali Apahapsili (Yali); C) Yali Gilika (Mek); and 2) Yali Mek in Yahukimo: A) Yali Anggruk (Yali); B) Yali Ninia (Yali); C) Yali Kosarek (Mek). [Source: Wikipedia]

The Yali can also be divided lingistically. 1) The Pass Valley Yali speak Pass Valley Yali. 2) The Ninia Yali speak Ninia Yali. And 3) The Angguruk Yali speak Angguruk Yali. Population estimates vary: in 1991 the Yali were believed to number between 15,000 and 30,000. The the 2010 Indonesian census counted 133,812 people, a figure that included the Ngalik. According to Joshua Project in the 2020s:1) the Pass Valley Yali numbered 8,300; 2) the Ninia Yali numbered 15,000; and 3) the Angguruk Yali Yali numbered 23,000. [Source: Joshua Project]

Most Yali today are Christians, predominantly Protestant. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project:1) 68 percent of Pass Valley Yali are Christians, wiith the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent; 2) 90 percent of Ninia Yali are Christians, wiith the estimated number of Evangelicals being 10 to 50 percent; 3) 60 percent of Angguruk Yali are Christians, wiith the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent.

Yali Life and Society

Yali eat sweet potatoes, beans, sugar cane and pigs. They live in smoky rectangular huts with pigs. A Yali village (opumbuk) usually has: 1) a yowi – men’s house; 2) a homea (homi) – women’s house; 3) a wam ibam – pig house; and 4) a usa yowi – sacred house for male rituals and initiation. Jawbones from pig feasts decorate the outside of the men's house.

The Yali grow sweet potatoes and taro using slash-and-burn shifting cultivation. They supplement their diet with hunting and gathering. Pigs are slaughter pigs during major celebrations such as weddings. Fruit is rarely eaten. In this patriarchal society, men hunt and build houses, while women grow crops and collect food.

Men still wear long, narrow penis gourds (humi) and hoop skirts made of rattan wrapped around their waists, a combination known as sabiyab. The number of rattan rings signified prestige, since rattan had to be obtained from outside Yali territory. The rings also served as fire starters. Men sometimes wear pointed hair nets decorated with cassowary, cuscus, or sugar glider fur, and paint their skin with clay or charcoal. Boar tusks may be worn as necklaces or nose ornaments. Women wear a short reed skirt called kem or kem lahuog, and carry noken tree fiber bags (sum) that are slung around their foreheads and hang down their backs. Today, shirts, trousers, skirts, and blouses are increasingly common.

The Yali are divided into two exogamous moieties, said to descend from brothers Winda and Waya (in Anggruk and Ninia: Kabak and Pahabol). Marriage within the same moiety is taboo and considered incest (pabi). Formerly punishable by death, the sanction is now less severe due to missionary influence. Clans (unggul) share a common origin myth and are grouped into larger units (unggul uwag), which in turn combine to form wilig lumpaleg—loosely comparable to confederations. Unlike Dani alliances, Yali confederations may unite clans from the same moiety. An even larger grouping, ap ahe, consists of clans whose members are spread across various regions and may now belong to other tribes such as the Lani and Dani, yet are still believed to share a single founding ancestor.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Peter Van Arsdale and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Geographic,, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Encyclopedia.com, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025